Abstract

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are an outstanding model of liver cancer induction by environmental chemicals and development of strategies for chemoprevention. Trout have critical and unique advantages allowing for cancer studies with 40,000 animals to determine dose-response at levels orders of magnitude lower than possible in rodents. Examples of two promoters in this model, the dietary supplement dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and industrial chemical perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), are presented. In addition, indole-3-carbinol (I3C) and chlorophyllin (CHL) inhibit initiation following exposure to potent human chemical carcinogens (e.g., aflatoxin B1 (AFB1). Two “ED001” cancer studies have been conducted, utilizing approximately 40,000 trout, by dietary exposure to AFB1 and dibenzo[d,e,f,p]chrysene (DBC). These studies represent the two largest cancer studies ever performed and expand the dose-response dataset generated by the 25,000 mouse “ED01” study over an order of magnitude. With DBC, the liver tumor response fell well below the LED10 line, often used for risk assessment, even though the biomarker (liver DBC-DNA adducts) remained linear. Conversely, the response with AFB1 remained relatively linear throughout the entire dose range. These contributions to elucidation of mechanisms of liver cancer, induced by environmental chemicals and the remarkable datasets generated with ED001 studies, make important contributions to carcinogenesis and chemoprevention.

Introduction

Rainbow trout have been utilized as a model for human cancer, especially liver cancer, at Oregon State University (OSU) for over 40 years (reviewed in Bailey et al., 1996; Walter et al., 2008). This species demonstrates a remarkable sensitivity to the mycotoxin and potent human liver carcinogen, aflatoxin B1 (AFB1). Our group has demonstrated that the mechanism of cytochrome P450 bioactivation to AFB1-8,9--exo-epoxide, and production of the potent mutagenic and carcinogenic DNA adduct 8,9-dihydro-8-(N7-guanyl)-9-hydroxyaflatoxin B1, is similar in trout and mammals (Bailey, 1994; Bailey et al., 1996; Nunez et al., 1990). In addition, there are other similarities to human AFB1-initiated liver cancer including Ki-ras mutations, histopathology and alterations in gene expression (Fong et al., 1993; Hendricks et al., 1984a; Tilton et al., 2005). Although a great deal of the focus has been on AFB1 as the initiator, other classes of human carcinogens requiring metabolic activation including nitrosamines, 1,2-dibromoethane, 2-acetylaminofluorene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) such as benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), dibenzo[a,l]pyrene (DBP) and 7–12 dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) are effective in the trout model, as are direct acting carcinogens such as N-methyl-N′-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) (Bailey et al., 1996; Hendricks et al, 1985; 1995; Kelly et al., 1992 Walter et al., 2008)

Over the years liver cancer, initiated by environmental chemicals, has been demonstrated in this model to be subject to either inhibition or promotion by the addition of dietary supplements to our specially developed semi-synthetic diet, the Oregon Test Diet (OTD) (Lee et al., 1991). Among the environmental chemicals that promote liver cancer in trout are, other mycotoxins such as fumonisin, polyhalogenated biphenyls (PCBs) and other aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) ligands such as β-naphthoflavone (BNF), promoters of oxidative stress (e.g., t-butylhydroperoxide, hydrogen peroxide, carbon tetrachloride and choline deficiency) and even elevated rearing temperature (Bailey and Hendricks, 1988; Bailey et al., 1996; Carlson el al., 2001; Curtis et al., 1995; Fong et al., 1988; Walter et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2003). Estrogens, xenoestrogens, and phytoestrogens are liver tumor promotors in this model (Nunez et al., 1988; 1989; Williams et al., 1998). The examples presented here, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), both appear to function as liver tumor promoters via estrogenicity (Benninghoff et al., 2011a;b; Orner et al., 1995;1996a;b; 1998). With respect to chemoprevention of AFB1-initiated liver cancer, it is interesting to note that BNF, PCBs, and indole-3-carbinol (I3C), when administered in the diet prior to and concurrent with carcinogen exposure, inhibit tumorigenesis in contrast to promotion when given long-term post-initiation (Bailey and Hendricks, 1988; Bailey et al., 1996; Goeger et al., 1988; Nixon et al., 1984; Orner et al., 1998; Shelton et al., 1986).

I3C, a major component of cruciferous vegetables and a popular dietary supplement, is chemopreventive against cancer in a number of animal models (Aggarwal and Ichikawa, 2005). Owing to the power of statistical analysis when using large numbers of animals, we have documented the relative potency of I3C as an inhibitor and promoter of cancer across a wide dose-range of carcinogen doses (Bailey et al., 1991; Dashwood et al., 1990; 1988; 1989a). Further analysis of alterations in gene expression using custom microarrays (Tilton et al., 2006) has documented that I3C is a phytoestrogen in the trout and this appears to partially explain its promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis when given post-initiation (Oganesian et al., 1999; Tilton et al., 2006). I3C acts, at least in part, as a blocking agent when given prior to and concurrent with the carcinogen by induction of phase I and phase II enzymes that metabolize and detoxify the procarcinogen (Dashwood et al., 1988; 1989a; Nixon et al., 1984).

Trout were the first animal model in which chlorophyllin (CHL) and natural chlorophylls (Chl) were demonstrated to be anticarcinogens (Breinholt et al., 1995a). Further study of the mechanism of CHL and Chl chemoprevention showed that complexation with carcinogens containing planar aromatic structure reduced bioavailability (Breinholt et al., 1995b; Hayashi et al., 1999). CHL was shown to be effective in a human clinical trial in Qidong, China where dietary exposure to AFB1 is high (Egner et al,. 2001). CHL, given over a 4 month period, reduced the urinary biomarker of AFB1 exposure, aflatoxin-N7-guanine, by 55% (Egner et al., 2001). Subsequently, a study led by Dr. George Bailey at OSU, in partnership with Dr. Kenneth Turteltaub at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, examined the impact of CHL and Chl on [14C]-AFB1 bioavailability in humans (Jubert et al., 2009).

Finally, results from two “ED001” studies will be presented. These studies each employed more than 40,000 animals and determined the shape of the dose-response curve down to levels less than 1 tumor per 1,000 animals. These studies were done with two different classes of environmental chemicals classified as human carcinogens, the PAH, DBC (previously referred to in the literature as dibenzo[a,l]pyrene or DBP) and AFB1. These studies represent the two largest chemical cancer datasets ever produced and have the potential to be very valuable in risk assessment. The DBC study has been published in its entirety (Bailey et al., 2009) as have partial results from the AFB1 study (Williams et al., 2009) which, although complete, has not yet been published.

Materials and Methods

As this paper represents a synopsis of a number of studies, this section will describe how trout cancer studies employed various methods of carcinogen exposure and dietary administration of tumor modulators. The experimental design of the ED001 studies will also be described.

Tumor studies with dietary inhibitors and promoters

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Mt. Shasta strain) were spawned and raised at the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory (SARL). This facility was equipped with 300 3–4 ft. diameter tanks capable of growing out trout for the typical 10–12 month cancer studies at which time the trout would weigh between 100 and 150 g. Constant flowing well water (12–14°C) was used for rearing and the trout kept on a 12 hour light/dark cycle. Embryos were obtained from 2 or 3 year old trout which spawned either in summer or winter. This species normally spawns only in the winter but we built a special “reverse photoperiod” room which allowed us to spawn these fish in the summer as well. Other modifications we made were utilization of custom-built silos containing 16,000 lbs of activated charcoal for filtration, and a UV sterilizer. In order to reduce the flow required we also equipped the tanks with air blowers and stones for maximal oxygen saturation. The trout were also protected from potential mortality due to interrupted water flow due to power outage by equipping the facility with natural gas generators that would automatically engage in case of an interruption in power to the facility.

Trout have been exposed to carcinogens employing a number of strategies (Table 1). We, and others, have utilized embryo exposure by immersion or microinjection (Dashwood et al., 1994; Hendricks et al., 1984a; Metcalf and Sonstegard, 1984; Sinnhuber et al., 1977). Microinjection can also be effectively performed at the sac-fry stage. Fry were usually acclimated to OTD prior to administration of OTD containing the test material (carcinogen, chemopreventive agent or promoter). Hydrophobic compounds were typically added to the fish oil component of the diet prior to mixing and hydrophilic compounds added to the water fraction. In the design for studying chemopreventive, or blocking agents, diets containing the test compound would typically be fed for 1–2 weeks prior to feeding diets containing both the test compound and the chemical carcinogen for various periods of time. When dietary agents were being tested as potential tumor promoters, they would be administered in diet following treatment with the carcinogen, often until the study was terminated (10–12 months of age). At the conclusion of the study, trout would be euthanized with an overdose of buffered MS-222 and a gross necropsy performed. All procedures for the rearing, treatment and handling of these animals were approved for every study by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Tissues were fixed in Bouin’s solution and histopathology performed by Dr. Jerry Hendricks according to criteria he has developed and published over the years (Hendricks et al., 1984b).

Table 1.

Methods for Carcinogen Administration in the Trout Tumor Model

| Compound | Exposure Route | Target Organs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene (DBP) | Diet | ST, LV, SB | (Bailey et al., 2009; Bailey et al., 1996; Reddy al., 1999 1999a; b; Pratt et al., 2007) |

| Microinjection, embryo | LV | ||

| Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) | Diet | LV | (Hendricks et al., 1985; Bailey et al., 1996) |

| i.p. injection | LV | ||

| Microinjection, embryo | LV | ||

| 7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) | Diet | ST, LV | (Fong et al., 1993; Bailey et al., 1996) |

| Water, embryo | LV, ST, K | ||

| Water, fry | ST, LV, SB, K | ||

| Microinjection, embryo | LV, ST | ||

| (±)-trans-B[a]P-7,8-dihydrodiol | Microinjection, sac-fry | LV | (Kelly et al., 1993a; Bailey et al., 1996) |

| Microinjection, embryo | |||

| (+)-11,12-DBP-dihydrodiol | Microinjection, embryo | LV | (Kelly et al., 1993a; 1993b) |

| (−)-11,12-DBP-dihydrodiol | Microinjection, embryo | LV | (Kelly et al., 1993a; 1993b) |

| (+)-syn-11,12-DBP-dihydrodiol epoxide | Microinjection, embryo | LV | (Kelly et al., 1993a; 1993b) |

| (−)-anti-11,12 DBP-dihydrodiol epoxide | Microinjection, embryo | LV | (Kelly et al., 1993a; 1993b) |

ST= stomach; LV= liver; K= kidney, SB= swim bladder.

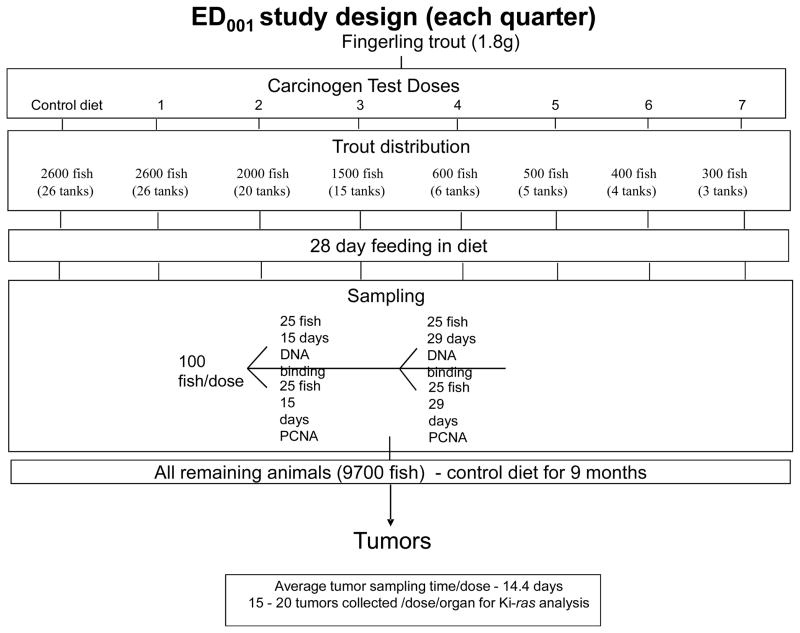

The ED001 studies were performed in quartiles of approximately 10,000 so that the time for necropsy would not exceed approximately 1 month (this ensured that age/growth would not impact the results). The statistician, Dr. Clifford Pereira, also developed a system for randomizing the trout to be euthanized by tank and dose so as to eliminate this potential confounder. Dr. Pereira also used statistical modeling to determine how many tanks/animals we would need per dose and for the controls (approximately 10,000 for the controls and lowest carcinogen dose, see Figure 1). DBC or AFB1 were administered in the diet for 4 weeks and then the animals switched to OTD for the remainder of the study. In this way, the trout ED001 study design differs from rodent carcinogen tests which are usually lifetime exposures. Quality control was performed with diet to ensure that the actual dose was close to the target dose. A sub-sample from each dose would be removed at the conclusion of carcinogen exposure to access a number of biomarkers (DNA adducts, cell proliferation, apoptosis, etc.).

Figure 1.

Design of a Trout ED001 Tumor Study Performed in Quartiles

Results and Discussion

The DHEA story

DHEA is found in most animals at high levels. In humans, it is the steroid found in blood at the second highest concentration (mostly as the 3β-sulfate). Interestingly, levels of DHEA decline with age in humans which, in part, explains the public interest in marketing this supplement as an anti-aging compound ( Bauleiu, 1996). DHEA can be converted in one enzymatic reaction to an androgen and then, following the action of aromatase, estrogen. This also explains, in part, why it has been marketed as a “natural” libido enhancer (for both sexes) (DHEA “After Dark”, Barth Vitamin Corp.) and as an alternative to hormone replacement therapy for post-menopausal women. Our initial interest in testing DHEA in the trout tumor model was borne out of the observation that in rodents DHEA was also a peroxisome proliferator and hepatocarcinogen (Rao et al., 1992a; b). As trout had been shown to be similar to humans in being resistant to peroxisome proliferation by compounds such as clofibrate and WY14,643 (Orner et al., 1995) we were testing the hypothesis that DHEA would not be a peroxisome proliferator in this model and would fail to produce liver cancer. We were somewhat surprised to find that, although DHEA did indeed fail to cause peroxisome proliferation in trout liver, it effectively promoted AFB1- or MNNG-initiated liver cancer (Orner et al., 1995; 1996a; b; 1998). Clofibrate and WY14,643 did not induce peroxisome proliferation nor did they promote liver cancer in trout (Orner et al., 1995). Subsequent experiments documented that the mechanism of DHEA promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis was due to it estrogenic properties (Benninghoff, 2011a; Orner et al. 1996a; Tilton, et al., 2008). Although these studies generated some interest in the public, the risks implied from our studies for supplementation with DHEA for long periods of time with respect to liver damage where largely ignored by regulatory agencies and discounted by supplement manufactures’ (“it’s a fish!). In this case, we tried to make the argument that “this fish” may be a better model than rodents for determining the human health risks associated with long-term high-dose DHEA supplementation.

The PFOA story

PFOA is a member of a class of chemicals known as polyfluorinated chemicals (PFCs) and have been widely used in industry as surfactants, coatings for textiles and papers fire-retardants and even in food packaging (Fromme et al., 2009). As a result, along with the resistance to biodegradation and metabolism, PFCs are found in blood samples from a high percentage of the population (Fromme et al., 2009). PFOA and PFOS (the sulfate of PFOA), have been assayed at levels of 4 and 20 ppb, respectively. Levels in wildlife and occupationally exposed humans can be much higher sometimes approaching ppm levels (Calafat et al., 2007; Emmet et al., 2006). Our interest in testing PFOA as a potential tumor promoter in the trout model originated in the same fashion as for DHEA as PFOA has been demonstrated to be a liver tumor promoter in rats (Lai, 2004). We found that, as with DHEA, post-initiation treatment with dietary PFCs (100–2000 ppm) resulted in tumor promotion and the mechanism was independent of peroxisome proliferation and appeared, in part, to be due its ability to function as a xenoestrogen in this model (Benninghoff, 2011a; b). We found a number of PFCs, including PFOA, to be relatively weak ligands for trout liver estrogen receptor (ER) compared to the natural ligand (IC50 for displacing 3H-β-estradiol (E2) of 1.8 mM, compared to E2 (14 nM). Comparison of this binding affinity also showed that PFOA was similar in potency to the phytoestrogen I3C (see below) and xenoestrogen 4-nonylphenol (0.8 mM) and considerably weaker than the well-characterized phytoestrogen genistein (1 μM). Nevertheless, PFOA (and other PFCs) were documented to bind to human ERα and activate estrogen receptor ERα-dependent transcription (Benninghoff et al., 2011a). Docking studies showed that a number of PFCs, including PFOA, fit well into the ligand binding site for ERα (Benninghoff et al., 2011a). The blood levels of PFOA measured at dietary exposures, resulting in effective promotion of AFB1- or MNNG-initiated liver cancer, are in the μM range, 3–4 orders of magnitude higher than blood levels found in the general population (Calafat et al., 2007; Fromme et al., 2009; Kannan et al., 2004). Does this mean PFCs are unlikely to be an environmental health risk? One has to take into account that the blood level and tumor promotion data in trout were not a lifetime exposure, some wildlife and humans living near industrial sites have blood levels at least an order of magnitude higher than the general population and, importantly, evidence indicates that this effect is probably additive. Using custom microarrays for trout, we found a number of PFCs altered the liver transcriptome in a manner consistent with natural estrogens (E2, DHEA) and phytoestrogens (I3C) although Venn diagrams demonstrated some distinct differences (Tilton et al., 2008). This work, carried out primarily by Dr. Abby Benninghoff (now at Utah State University) was the first comprehensive study of a wide range of PFCs in a single species and documented that this important class of industrial environmental contaminants were capable of activating ER-dependent transcription and were promoters of liver cancer. This dataset should be of considerable value to regulatory agencies and, again, showed the value and versatility of the trout tumor model.

The I3C story

I3C is present in cruciferous vegetables as glucobrassicin which is hydrolyzed by the enzyme myrosinase producing I3C as the major product (McDanell et al., 1988). A number of laboratories have studied the chemopreventive properties of I3C for a number of years in various animal models and in human clinical trials (Aggarwal and Ichikawa, 2005; Reed et al., 2005). One of the often overlooked issues with this natural dietary component and supplement is that the study of I3C is really a study of mixtures. I3C, taken orally, rapidly undergoes acid-catalyzed polymerization reactions to form a complex mixture of dimers, trimers and tetramers as well as other derivatives (Bjeldanes et al., 1991). In fact, relatively little parent compound appears to be absorbed from the GI tract following dosing of animals or humans (Anderton et al., 2004; Dashwood et al., 1989b; Reed et al., 2006; Stresser et al., 1995). As in mammalian cancer chemoprevention models, I3C fed to trout prior to administration of the carcinogen AFB1, acts as a blocking agent most likely through induction of glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs) with high activity toward conjugation and inactivation of the AFB1-8,9-exo-epoxide (Aggarwal and Ichikawa, 2005; Stresser et al., 1994). Our group was the first to demonstrate that long-term, post-initiation, dietary I3C led to enhancement of liver cancer (Bailey et al., 1987) and we performed studies with large numbers of animals in efforts to determine the mechanism of promotion and the relative risk/benefit of dietary I3C (Oganesian et al., 1999). I3C and a major acid condensation product, 3,3-diindolylmethane (DIM, also sold as a supplement), were found to be phytoestrogens (Oganesian et al., 1999; Shilling and Williams, 2000; Shilling et al., 2001; Benninghoff and Williams, 2008; Benninghoff et al., 2011a). Subsequent studies in a rat model demonstrated that post-initiation promotion of liver cancer by I3C as not limited to the trout (Xu et al., 2001). With respect to I3C, the trout model, again, made important contributions to human health by documenting the potential risk of high dose, long-term exposure.

The CHL and Chl story

CHL, the water soluble, copper-containing derivative of Chl, had been documented to be anti-mutagenic but it was first demonstrated to be an effective anti-carcinogen in the trout model (Breinholt et al., 1995a). Inhibition of carcinogen-DNA adduction in the trout liver tumor model suggested that chlorophylls could also be anticarcinogens (Harttig and Bailey, 1998). Natural chlorophylls were later confirmed to function as dietary inhibitors of hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo with the trout model and also in the rat (Simonich et al., 2007; 2008). Physical complexation with the carcinogen, resulting in reduced bioavailability, appeared to be a significant mechanism for this chemoprevention (Breinholt et al., 1995b; Hayashi et al., 1999). Dr. George Bailey participated in a study in China led by Drs. Tom Kensler and John Groopman at Johns Hopkins University where co-administration of CHL significantly reduced a urinary biomarker of AFB1 exposure and toxicity (Egner et al., 2001). Dr. Bailey then conducted a study with human volunteers at OSU in collaboration with Dr. Ken Turteltaub at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Due to the sensitivity of accelerator mass spectrometry, it is possible to do a fairly complete bioavailability/elimination kinetics study with only 5 nCi of [14C]-AFB1. With the specific activity available, this amounted to a mass of around 30 ng, less than an exposure obtained from eating a single peanut butter sandwich. The results convincingly documented that co-treatment of individuals with CHL or Chl and AFB1 significantly reduced the area under the curve (AUC) and thus exposure (Jubert et al., 2009). Dr. Bailey has been able to perform the first tumor modulation studies with Chl (prohibitively expensive if obtained commercially) by development of a counter-current-chromatography method to efficiently purify Chl from spinach (Jubert and Bailey, 2007). Sufficient Chl was obtained to not only perform the human volunteer study but to do a dose-dose matrix design experiment with Chl and the carcinogen DBC in 12,000 trout (McQuistan et al., 2011) as was previously done with CHL (Pratt et al., 2007). These studies emphatically demonstrate the value of the trout model as it played a significant role in development of CHL (and perhaps Chl) as a cancer chemopreventive agent for humans. This was truly an example of translational research.

ED001 studies: how trout took cancer risk assessment to the next level

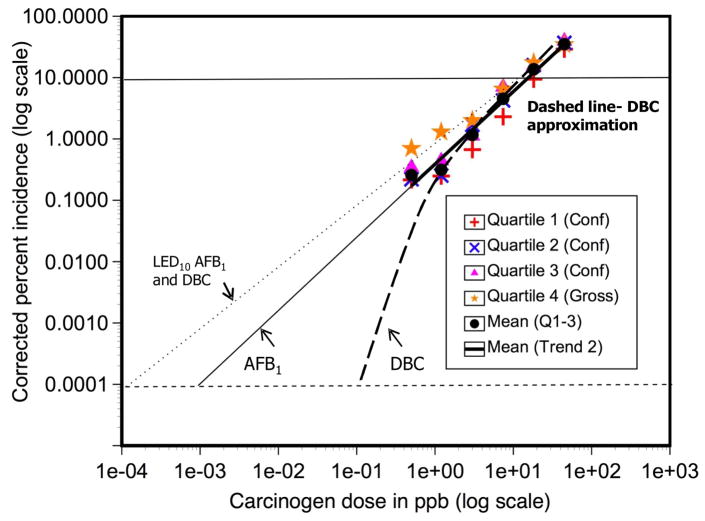

The relatively low cost of rearing trout, the large capacity of our facility and the low spontaneous (historically about 0.1%) tumor background in rainbow trout (among other advantages), encouraged us to undertake the two largest chemical cancer studies ever performed in an animal model. A total of 40,800 trout were utilized in an “ED001” study with dietary exposure to DBC for a period of 4 weeks. A typical design of a trout ED001 study is shown in Figure 1. A number of trout are sampled following carcinogen exposure to measure various biomarkers. The remaining trout were reared to approximately one year of age and then necropsied followed by histopathology for tumor confirmation as previously described (Bailey et al., 2009). The DBC doses (ppm in OTD diet) and number of animals necropsied (in parentheses) were 0 (8,363), 0.45 (8,848), 1.27 (6,429), 3.57 (4,535), 10.1 (1,558), 28.4 (1,211), 80 (931) and 225 (541); again, performed in quartiles from 4 separate spawnings over 2 years. The complete description and results of this study have been published (Bailey et al., 2009). A few of the very significant findings that came from these studies with potential major impacts for regulatory agencies, are as follows: 1) the study actually exceeding the target of a ED001 study and was able to determine the dose of DBC resulting in 1 additional cancer in 5,000 animals (ED0002); 2) the shape of the dose-response curve, analyzed by a number of statistical models, sharply deviated from the Linear Extrapolated Dose (LED) line with the response increasing falling below the LED10 line with decreasing dose; 3) as a consequence, the extrapolated dose-response curve crossed the y-axis at 1 cancer in 106 at a dose 500–1500-fold (depending on the statistical model) higher than would have been predicted from the LED10 (Bailey et al., 2009) and 4) the biomarker commonly used to estimate carcinogenic potency, covalent DBC-DNA adducts, remained linear with dose (Bailey et al., 2009). As the exposure or dose of a carcinogen that would be predicted to cause 1 additional cancer per million individuals is often used for risk assessment, the default LED10 extrapolation would have predicted a dose three orders of magnitude lower than indicated by the actual tumor data.

A second “ED001” study was designed and undertaken, this time with AFB1 as the carcinogen. The experimental design was similar to the DBC study (Figure 1). A great deal more risk assessment with AFB1 as a carcinogen, as well as determination of human exposures, has been done; DBC is not often studied individually and many of the regulatory standards are based on BaP. A plot of AFB1-DNA adducts versus dose is linear for both rats and trout and the slopes are almost identical (Bechtel, 1989). If the LED is used to estimate potency, one gets a value of 6.25 × 10−4 ng/Kg/day (Eaton and Gallagher, 1994). The average daily intake of AFB1 in peanuts alone in the Southeastern U.S. is listed as 110 ng/Kg (Eaton and Gallagher, 1994). Using these numbers, it was estimated that AFB1 alone should produce about 98/100,000 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), approximately 20-fold higher than all of the HCC diagnosed annually in the U.S.(Eaton and Gallagher, 1994). The doses utilized in the AFB1 ED001 study were 0, 0.5, 1.2, 3.0, 7.4, 18.2, 44.8 and 110 ppb given in the diet for 4 weeks. The data have not as yet been peer-reviewed. The quartiles exhibited slightly greater variability than with DBC. However, it is readily apparent, that unlike DBC, the liver tumor response to AFB1 remained linear to the lowest dose although the slope was about 1.4–1.5 and the predicted dose resulting in 1 cancer in 106 was about 10-fold higher than predicted from the extrapolated LED10 line (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of ED001 Dose Response with AFB1 and DBC

Conclusions

Rainbow trout have proven versatile in studying the mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis, the response to dietary modulators and, owing to the capabilities of our unique facility at OSU, chemoprevention and tumor promotion with thousands of animals. The two ED001 studies with DBC and AFB1 represent the largest tumor studies ever conducted and the richest data set available for risk assessment with these human carcinogens. The results from both studies eclipsed the mouse ED01 study with 2-acetylaminofluorene by 1–2 orders of magnitude. The 25,000 mouse ED01 study would be prohibitively expensive to conduct again whereas the trout model is relatively inexpensive. There are, of course, disadvantages as is the case with any model some of which include the fact that a facility with a capacity such as the SARL at OSU is required, a number of important human cancers simply cannot be studied (e.g., breast, lung, prostate), their indeterminate life span prevent conduct of lifetime exposures such as performed with rodents, etc. However, the range of response of trout to many chemical classes of human carcinogens make them a useful model for addressing a number of mechanistic hypotheses as well as the conduct of the type of experiments described in this short synopsis. As toxicologists move into adapting Toxicology Testing in the 21st Century, it would seem that, along with human cell lines and other tools, the trout could occupy an important niche in cancer risk assessment and continue to play a role in studies directed at protecting human health.

Acknowledgments

There are too many outstanding individuals that have worked on the trout model over the 40 plus years and too many individual NIH grants to list them all here (although this author would like to acknowledge the grant that supported the AFB1 ED001 study, ES013534. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Russell Sinnhuber and his co-workers who first pioneered the use of this model. A great deal of the research listed here was directed by Dr. George Bailey who has been a tireless champion and spokesman for the model. Dr. Jerry Hendricks, one of the most renowned aquatic pathologists worldwide, helped to design some of these studies and performed almost all of the histopathology, probably looking at close to a million slides at the time of his recent retirement. Cliff Pereira from Statistics at OSU is to be thanked for his patience and diligence in helping us biologists design and interpret large tumor studies in the proper manner. Again, there are many individuals that made significant contributions over the years that I am not able to list here but you will find them as authors in the papers cited in this and other manuscripts.

Footnotes

This paper is based on a presentation given at the 5th Aquatic Annual Models of Human Disease conference: hosted by Oregon State University and Texas State University-San Marcos, and convened at Corvallis, OR, USA September 20-22, 2010.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aggarwal BB, Ichikawa H. Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1201–1215. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.9.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderton MJ, Manson MM, Verschoyle RD, Gescher A, Lamb JH, Farmer PB, Steward WP, Williams ML. Pharmacokinetics and tissue disposition of indole-3-carbinol and its acid condensation products after oral administration to mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5233–5241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GS. The Toxicology of Aflatoxins: Human Health, Veterinary, and Agricultural Significance. Academic Press; 1994. Role of aflatoxin-DNA adducts in the cancer process; pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G, Hendricks J. Environmental and dietary modulation of carcinogenesis in fish. Aquat Toxicol. 1988;11:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GS, Dashwood RH, Fong AT, Williams DE, Scanlan RA, Hendricks JD. Modulation of mycotoxin and nitrosamine carcinogenesis by indole-3-carbinol: quantitative analysis of inhibition versus promotion. In: O’Neill IK, Chen J, Bartsch H, editors. Relevance to Human Cancer of N-Nitroso Compounds, Tobacco Smoke and Mycotoxins. IARC; 1991. pp. 275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GS, Reddy AP, Pereira CB, Harttig U, Baird W, Spitsbergen JM, Hendricks JD, Orner GA, Williams DE, Swenberg JA. Non-linear cancer response at ulta-low dose: a 40,800-animal ED001 tumor and biomarker study. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1264–1276. doi: 10.1021/tx9000754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G, Selivonchick D, Hendricks J. Initiation, promotion, and inhibition of carcinogenesis in rainbow trout. Environm Hlth Perspect. 1987;71:147–153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8771147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey GS, Williams DE, Hendricks JD. Fish models for environmental carcinogenesis: the rainbow trout. Environ Hlth Persp. 1996;104 (Suppl):5–21. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauleiu EE. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): a fountain of youth? J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1996;81:3147–3151. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.9.8784058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel DH. Molecular dosimetry of hepatic aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts: linear correlation with hepatic cancer risk. Reg Toxicol Pharmacol. 1989;10:74–81. doi: 10.1016/0273-2300(89)90014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninghoff AD, Williams DE. Identification of a transcriptional fingerprint of estrogen exposure in rainbow trout liver. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101:65–80. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninghoff AD, Bisson WH, Koch DC, Ehresman DJ, Kolluri SK, Williams DE. Estrogen-like activity of perfluoroalkylacids in vivo and interaction with human and rainbow trout estrogen receptors in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2011a;120:42–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninghoff AD, Orner GA, Buchner C, Hendricks JD, Williams DE. Promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis by perfluoroalkyl acids in rainbow trout. Environm Hlth Perspect. 2011b doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr267. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjeldanes LF, Kim JY, Grose KR, Bartholomew JC, Bradfield CA. Aromatic hydrocarbon responsiveness-receptor agonists generated from indole-3-carbinol in vitro and in vivo: comparisons with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1991;88:9543–9547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breinholt V, Hendricks J, Pereira C, Arbogast D, Bailey GS. Dietary chlorophyllin is a potent inhibitor of aflatoxin B1 hepatocarcinogenesis in rainbow trout. Cancer Res. 1995a;55:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breinholt V, Schimerlk M, Dashwood R, Bailey GS. Mechanisms of chlorophyllin anticarcinogenesis against aflatoxin B1: complex formation with the carcinogen. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995b;8:506–514. doi: 10.1021/tx00046a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Polyfluoroalky chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparison with NHANES 1999–2000. Environm Hlth Perspect. 2007;115:1596–1602. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DB, Williams DE, Spitsbergen JM, Ross PF, Bacon CW, Meredith FI, Riley RT. Fumonisin B1 promotes aflatoxin B1 and N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-initiated liver tumors in rainbow trout. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;172:29–36. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis LR, Zhang Q, El-Zahr C, Carpenter HM, Miranda CL, Buhler DR, Selivonchick DP, Arbogast DN, Hendricks JD. Temperature-modulated incidence of aflatoxin B1-initiated liver cancer in rainbow trout. Fund Appl Toxicol. 1995;25:146–153. doi: 10.1006/faat.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Arbogast DN, Fong AT, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Mechanisms of anti-carcinogenesis by indole-3-carbinol: detailed in vivo DNA binding dose-response studies after dietary administration with aflatoxin B1. Carcinogenesis. 1988a;9:427–432. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Arbogast DN, Fong AT, Pereira C, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Quantitative inter-relationships between aflatoxin B1 carcinogen dose, indole-3-carbinol anti-carcinogen dose, target organ DNA adduction and final tumor response. Carcinogenesis. 1989a;10:175–181. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Fong AT, Arbogast DN, Bjeldanes LF, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Anticarcinogenic activity of indole-3-carbinol acid products: ultrasensitive bioassay by trout embryo microinjection. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3617–3619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Fong AT, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Tumor dose-response studies with aflatoxin B1 and the ambivalent modulator indole-3-carbinol: inhibitory versus promotional potency. In: Kuroda Y, Shankel DM, Water MD, editors. Antimutagenesis and Anticarcinogenesis Mechanism II. Plenum Publishing; 1990. pp. 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Uyetake L, Fong AT, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. In vivo disposition of the natural anti-carcinogen indole-3-carbinol after po administration to rainbow trout. Fd Chem Toxicol. 1989b;27:385–392. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(89)90144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DL, Gallagher EP. Mechanisms of aflatoxin carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;34:135–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.34.040194.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner PA, Wang JB, Zhu YR, Zhang BC, Wu Y, Zhang QN, Qian GS, Kuang SY, Gange SJ, Jacobson LP, Helzisouer KJ, Bailey GS, Groopman JD, Kensler TW. Chlorophyllin intervention reduces aflatoxin-DNA adducts in individuals at high risk for liver cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2001;98:14601–14606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251536898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett EA, Shofer FS, Zhang H, Freeman D, Desai C, Shaw LM. Community exposure to perfluorooctanoate: relationships between serum concentrations and exposure sources. J Occup Environm. 2006;48:759–770. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000232486.07658.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong AT, Dashwood RH, Cheng R, Mathews C, Ford B, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Carcinogenicity, metabolism and Ki-ras proto-oncogene activation by 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene in rainbow trout embryos. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:629–635. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong AT, Hendricks JD, Dashwood RH, Van Winkle S, Lee BC, Bailey GS. Modulation of diethyl nitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis and O6-ethylguanine formation in rainbow trout by indole-3-carbinol, β-naphthoflavone, and Aroclor 1254. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1988;96:93–100. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H, Tittlemier SA, Volkel W, Wilhelm M, Twardella D. Perfluorinated compounds—exposure assessment for the general population in Western countries. Int J Hyg Environm Hlth. 2009;212:239–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeger DE, Shelton DW, Hendricks JD, Pereira C, Bailey GS. Comparative effect of dietary butylated hydroxyanisole and β-naphthoflavone on aflatoxin B1 metabolism, DNA adduct formation, and carcinogenesis in rainbow trout. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:1793–1800. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.10.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harttig U, Bailey GS. Chemoprotection by natural chlorophylls in vivo: inhibition of dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-DNA adducts in rainbow trout liver. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1323–1326. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.7.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Schimerlik M, Bailey GS. Mechanisms of chlorophyllin anticarcinogenesis: dose-response inhibition of aflatoxin uptake and biodistribution following oral co-administration in rainbow trout. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;158:132–140. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JD, Meyers TR, Casteel JR, Nixon JE, Loveland PM, Bailey GS. Rainbow trout embryos: advantages and limitations for carcinogenesis research. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1984a;65:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JD, Meyers TR, Shelton DW. Histological progression of hepatic neoplasia in rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984b;65:643–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JD, Meyers TR, Shelton DW, Casteel JL, Bailey GS. Hepatocarcinogenicity of benzo[a]pyrene to rainbow trout by dietary exposure and intraperitoneal injection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:839–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JD, Shelton DW, Loveland PM, Pereira CB, Bailey GS. Carcinogenicity of dietary dimethylnitrosomorpholine, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine, and dibromoethane in rainbow trout. Toxicol Pathol. 1995;23:447–457. doi: 10.1177/019262339502300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubert C, Bailey G. Isolation of chlorophylls a and b from spinach by counter-current chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1140:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubert C, Mata J, Bench G, Dashwood R, Pereira C, Tracewell W, Turteltaub K, Williams DE, Bailey GS. Effects of chlorophyll and chlorophyllin on low-dose aflatoxin B1 pharmacokinetics in human volunteers. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:1015–1022. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan K, Corsolini S, Falandysz J, Fillmann G, Kumar KS, Loganathan BG, Mohd MA, Olivero J, Van Wouwe N, Yang JH, Aldoust KM. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorochemicals in human blood from several countries. Environm Sci Technol. 2004;38:4489–4495. doi: 10.1021/es0493446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Dutchuk M, Hendricks JD, Williams DE. Hepatocarcinogenic potency of mixed and pure enantiomers of trans-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol in trout. Cancer Lett. 1993a;68:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Dutchuk M, Takahashi N, Reddy A, Hendricks JD, Williams DE. Covalent binding of (+) 7S-trans-7,8-dihydrobenzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol to trout DNA. P450- and peroxidation-dependent pathways. Cancer Lett. 1993b;74:111–117. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(93)90052-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JD, Orner GA, Hendricks JD, Williams DE. Dietary hydrogen peroxide enhances hepatocarcinogenesis in trout: correlation with 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels in liver DNA. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:1639–1642. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.9.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai DY. Rodent carcinogenicity of peroxisome proliferators and issues on human relevance. J Environm Sci Hlth. 2004;22:37–55. doi: 10.1081/GNC-120038005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BC, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Toxicity of mycotoxins in the feed of fish. In: Smith JE, editor. Mycotoxins and Animal Feedstuff: Natural Occurrence, Toxicity and Control. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1991. pp. 607–626. [Google Scholar]

- McDanell R, McLean AE, Hanley AB, Heaney RK, Fenwick GR. Chemical and biological properties of indole glucosinolates (glucobrassicin): a review. Fd Chem Toxicol. 1988;26:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(88)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuistan TJ, Simonich MT, Pratt MM, Pereira CB, Hendricks JD, Dashwood RH, Williams DE, Bailey GS. Cancer chemoprevention by dietary chlorophylls: A 12,000-animal dose-dose matrix biomarker and tumor study. Cancer Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.10.065. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf CD, Sonstegard RA. Microinjection of carcinogens into rainbow trout embryos: an in vivo carcinogenesis assay. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:1125–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon JE, Hendricks JD, Pawlowski NE, Pereira CB, Sinnuhuber RO, Bailey GS. Inhibition of aflatoxin B1 carcinogenesis in rainbow trout by flavones and indole compounds. Carcinogenesis. 1984;5:615–619. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez O, Hendricks JD, Arbogast DN, Fong AT, Lee BC, Bailey GS. Promotion of aflatoxin B1 hepatocarcinogenesis in rainbow trout by 17β-estradiol. Aq Toxicol. 1989;15:289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez O, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Enhancement of aflatoxin B1 and N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri by 17-B-estradiol and other organic chemicals. Dis Aq Org. 1988;5:185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez O, Hendricks JD, Fong AT. Inter-relationships among aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) metabolism, DNA-binding, cytotoxicity, and hepatocarcinogenesis in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Dis Aq Org. 1990;9:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Oganesian A, Hendricks JD, Pereira CB, Orner GA, Bailey GS, Williams DE. Potency of dietary indole-3-carbinol as a promoter of aflatoxin B1-initiated hepatocarcinogenesis: results from a 9000 animal tumor study. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:453–458. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner GA, Donohoe RM, Hendricks JD, Curtis LR, Williams DE. Comparison of the enhancing effects of dehydroepiandrosterone with the structural analog 16α-fluoro-5-androsten-17-one on aflatoxin B1 hepatocarcinogenesis in rainbow trout. Fund Appl Toxicol. 1996a;34:132–140. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner GA, Hendricks JD, Arbogast D, Williams DE. Modulation of N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine by dehydroepiandrosterone in rainbow trout. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996b;141:548–554. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner GA, Hendricks JD, Arbogast D, Williams DE. Modulation of aflatoxin B1 hepatocarcinogenesis in trout by dehydroepiandrosterone: initiation/post-initiation and latency effects. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:161–167. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner GA, Mathews C, Hendricks JD, Carpenter HM, Bailey GS, Williams DE. Dehydroepiandrosterone is a complete hepatocarcinogen and potent tumor promoter in the absence of peroxisome proliferation in rainbow trout. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2893–2998. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.12.2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MM, Reddy AP, Hendricks JD, Pereira C, Kensler TW, Bailey GS. The importance of carcinogen dose in chemoprevention studies: quantitative interrelationships between, dibenzo[a,l]pyrene dose, chlorophyllin dose, target organ DNA adduct biomarkers and final tumor outcome. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:611–624. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MS, Musunuri S, Reddy JK. Dehydroepiandrosterone-induced peroxisome proliferation in the rat liver. Pathobiol. 1992a;60:82–86. doi: 10.1159/000163703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MS, Subbarao V, Yeldandi AV, Reddy JK. Hepatocarcinogenicity of dehydroepiandrosterone in the rat. Cancer Res. 1992b;52:2977–2979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AP, Harttig U, Barth MC, Baird WM, Schimerlik M, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Inhibition of dibenzo[a,l]pyrene-induced multi-organ carcinogenesis by dietary chlorophyllin in rainbow trout. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1919–1926. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.10.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy AP, Spitsbergen JM, Mathews C, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Experimental tumorigenicity by environmental hydrocarbon dibenzo[a,l]pyrene. J Environm Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1999b;18:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed GA, Peterson KS, Smith HJ, Gray JC, Sullivan DK, Mayo MS, Crowell JA, Hurwitz A. A Phase I study of indole-3-carbinol in women: tolerability and effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1953–1960. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed GA, Arneson DW, Putnam WC, Smith HJ, Gray JC, Sullivan DK, Mayo MS, Crowell JA, Hurwitz A. Single-dose and multiple-dose administration of indole-3-carbinol to women: pharmacokinetics based on 3,3′-diindolylmethane. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2477–2481. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton DW, Goeger DE, Hendricks JD, Bailey GS. Mechanism of anti-carcinogenesis: the distribution and metabolism of aflatoxin B1 in rainbow trout fed Aroclor 1254. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1065–1071. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.7.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling AD, Williams DE. Determining relative estrogenicity by quantifying vitellogenin induction in rainbow trout liver slices. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;164:330–335. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilling AD, Carlson DB, Katchamart S, Williams DE. 3,3′-Diindolylmethane, a major condensation product of indole-3-carbinol, is a potent estrogen in the rainbow trout. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;170:191–200. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonich MT, Egner PA, Robuck BD, Orner O, Jubert C, Pereira C, Groopman JD, Kensler TW, Dashwood RH, Williams DE, Bailey GS. Natural chlorophyll inhibits aflatoxin B1 induced multi-organ carcinogenesis in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1294–1302. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonich MT, McQuistan T, Jubert C, Pereira C, Hendricks JD, Schimerlik M, Zhu B, Dashwood R, Williams DE, Bailey GS. Low-dose dietary chlorophyll inhibits multi-organ carcinogenesis in the rainbow trout. Fd Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:1014–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnhuber RO, Hendricks, Wales JH, Putnam GB. Neoplasms in rainbow trout, a sensitive animal model for environmental carcinogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1977;298:389–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb19280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresser DM, Williams DE, Griffin DA, Bailey GS. Mechanisms of tumor modulation by indole-3-carbinol. Disposition and excretion of [3H]indole-3-carbinol in male Fischer 344 rats. Drug Metabol Dispos. 1995;23:965–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stresser DM, Williams DE, McLellan LI, Harris TM, Bailey GS. Indole-3-carbinol induces a rat liver glutathione transferase subunit (Yc2) with high activity towards aflatoxin B1-exo-epoxide: association with reduced levels of hepatic AFB1-DNA adducts in vivo. Drug Metabol Dispos. 1994;22:392–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton SC, Gerwick LG, Hendricks JD, Rosato CS, Corley-Smith G, Givan SA, Bailey GS, Bayne CJ, Williams DE. Use of a rainbow trout oligonucleotide microarray to determine transcriptional patterns in aflatoxin B1-induced hepatocellular carcinoma compared to adjacent liver. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:319–330. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton SC, Givan SA, Pereira CB, Bailey GS, Williams DE. Toxicogenomic profiling of the hepatic tumor promoters indole-3-carbinol, β-estradiol and β-naphthoflavone in rainbow trout. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:61–72. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilton SC, Orner GA, Benninghoff AD, Carpenter HM, Hendricks JD, Pereira CB, Williams DE. Genomic profiling reveals an alternate mechanism for hepatic tumor promotion by perfluorooctanoic acid in rainbow trout. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1047–1055. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter RB, Timmins GS, Tilton SC, Orner GA, Benninghoff AD, Bailey GS, Williams DE. Carcinogenesis models: Focus on Xiphophorous and rainbow trout. In: Walsh PJ, editor. Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Seas. Elsevier; 2008. pp. 586–611. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, Bailey GS, Reddy A, Hendrick JD, Oganesian A, Orner GA, Pereira CB, Swenberg JA. The rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) tumor model: recent applications in low-dose exposures to tumor initiators and promoters. Toxicol Pathol. 2003;31(Suppl):58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, Lech JJ, Buhler DR. Xenobiotics and xenoestrogens in fish: modulation of cytochrome P450 and carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1998;399:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DE, Willard KD, Orner G, Hendricks JD, Pereira CB, Benninghoff A, Bailey GS. Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and ultra-low dose cancer studies. Comp Biochem Physiol Part C. 2009;149:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Orner GA, Bailey GS, Stoner GD, Horio DT, Dashwood RH. Post-initiation effects of chlorophyllin and indole-3-carbinol in rats given 1,2-dimethylhydrazine or 2-amino-3-methyl-imidazo[4,5-f]quinoline. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:309–314. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]