Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to examine extended postoperative ileus and its risk factors in patients who have undergone abdominal surgery, and discuss the techniques of prevention and management thereof the light of related risk factors connected with our study.

Methods

This prospective study involved 103 patients who had undergone abdominal surgery. The effects of age, gender, diagnosis, surgical operation conducted, excessive small intestine manipulation, opioid analgesic usage time, and systemic inflammation on the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility were investigated. The parameters were investigated prospectively.

Results

Regarding the factors that affected the restoration of gastrointestinal motility, resection operation type, longer operation period, longer opioid analgesics use period, longer nasogastric catheter use period, and the presence of systemic inflammation were shown to retard bowel motility for 3 days or more.

Conclusion

Our study confirmed that unnecessary analgesics use in patients with pain tolerance with non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, excessive small bowel manipulation, prolonged nasogastric catheter use have a direct negative effect on gastrointestinal motility. Considering that an exact treatment for postoperative ileus has not yet been established, and in light of the risk factors mentioned above, we regard that prevention of postoperative ileus is the most effective way of coping with intestinal dysmotility.

Keywords: Ileus, Abdominal surgery, Intestinal complications

INTRODUCTION

Despite the advancements in surgical techniques and preoperative care, postoperative ileus continues to be the most common complication of abdominal surgery [1]. In essence, postoperative leus can be described as the deceleration or arrest of intestinal motility following abdominal surgery or intra-abdominal trauma. Initially presenting with abdominal distension and cessation of defecation, postoperative ileus progresses with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps. This condition, which delays resumption of normal nutrition and mobilization, is one of the most significant causes of extended hospitalization following surgery. None of the pathophysiological or pharmacological methods proposed for the treatment of postoperative ileus incorporate a multimodal and effective approach. Although postoperative ileus is traditionally accepted as a physiological response to abdominal surgery, an exact definition regarding its formational mechanism, pathophysiology, and etiology has not yet been achieved. Additionally, few studies have investigated the frequency of, and risk factors and predisposing conditions for postoperative ileus in patients who have undergone major abdominal surgery for malignant cancers [2]. Thus, this study aimed to examine extended postoperative ileus cases in patients with malignant tumors, which correspond to the other ileus cases clinically encountered. Although the pathogenic mechanisms of postoperative ileus and numerous pharmacological approaches for this condition have been investigated, the most effective approach seems to be prevention of ileus by considering its etiology .

METHODS

This prospective study involved 103 patients who had undergone abdominal surgery between 2007 and 2009. The effects of age, gender, diagnosis, surgical operation conducted, excessive small intestine manipulation, opioid analgesic usage time, and systemic inflammation on the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility were investigated.

The operation, its possible complications, and its expected results were preoperatively explained to all of the patients by the surgical team, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. In addition, all patients were informed in detail about our study, and provided informed consent forms confirming their voluntary participation in the study. Our research was approved by the local ethics committee and complied with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

The following patients were excluded from the study: patients who had used opioid analgesics 4 weeks before the surgery; patients with serious cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, or hematologic diseases or other systemic illnesses; patients with severe biochemical derangement, as indicated in the preoperative workup; patients with mechanical obstruction; patients with inflammatory intestinal disease; patients with a psychiatric disorder or those who with a history of drug dependency; and patients with an orthopedic disorder that might limit patient mobilization during the postoperative period.

Premedication were not administered to the study patients. Following induction with 2 mg/kg of Diprivan, 0.1 mg/kg of vecuronium bromide, and 1 mg/kg of fentanyl, anesthesia was maintained with 40% oxygen of which 2% consisted of sevoflurane and 60% consisted of nitrous oxide. At the end of the operation, the neuromuscular block was reversed with 0.04 mg/kg of neostigmine methyl sulfate and 0.5 to 1 mg/kg of atropine sulfate. Following revival from anesthesia, 1 to 1.5 mg/kg of tramadole was infused with the intention of providing analgesia. Intraoperative fluid replacement was limited to 1,000 mL of isotonic saline solution +500 mL of 5% dextrose solution. Decisions regarding additional fluid infusions and blood transfusions were made intraoperatively by discussion with the anesthesiologist. The body temperature of the patient during the operation was maintained between 35.8℃ and 37℃. The patients were mobilized in the eighth postoperative hour. Ondansetron hydrochloride (8 mg as a single daily dose) was used as an antiemetic. Oral nutrition was delayed until normoactive intestinal sounds were detected or normal gas passing occurred.

On the first postoperative day, palliation was achieved with narcotic analgesics. From the second postoperative day, paracetamol 500 mg 2 × 1 was administered to the patients with sufficient analgesia and opioid analgesics were discontinued. Patients with insufficient analgesia continued to receive opioid analgesics. Patients were divided into 2 groups depending on their duration of narcotic analgesic use: 1) 0 to 3 days and 2) 3 days and more.

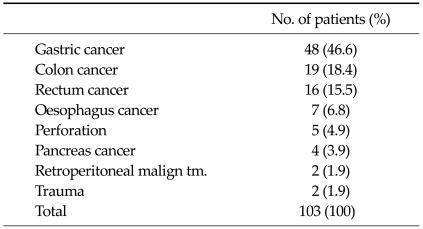

The diagnoses and specific operations performed were analyzed by separating patients into various groups. Grouping according to diagnosis was made as follows: 1) pancreatic malignant tumor; 2) gastric malignant tumor; 3) esophageal malignant tumor; 4) retroperitoneal malignant tumor; 5) trauma; 6) gastric or intestinal perforation; 7) rectal malignant tumor; and 8) colonic malignant tumor (Table 1). Grouping according to the operation performed was as follows: 1) debridement; 2) resection: 3) lavage; 4) drainage; 5) reconstruction; 6) re-anastomosis; and 7) diversion.

Table 1.

Preoperative diagnosis of patients

malign tm, malignant tumor.

A nasogastric catheter was placed in all patients during operation. From the second postoperative day, the nasogastric catheters were clamped and then removed in the case of the patients who could tolerate it. In patients who could not tolerate this, the nasogastric catheters were left in place until oral nutrition was started. Patients were also grouped according to the duration drainage with the nasogastric catheter: 1) up to 2 days and 2) for more than 2 days.

Cases of excessive small bowel manipulation were noted in patient case files, and patients were subsequently divided into 2 groups as those with and without excessive small bowel manipulation. Excessive small bowel manipulation defined as: small bowel surgery requiring more than 1 hour, small bowel anastomosis, small bowel adhesiolisis, small bowel bridectomy, local ischemia or petechia related with small bowel manipulation.

Patients diagnosed with systemic inflammation 24 hours before the operation were separated from those who did not have systemic inflammation. Systemic inflammation defined as the existence of 2 of these criterias: 1) hypo or hypertermia (>38℃, <36℃ ); 2) Tachicardia (>20/min); 3) Tachipnea (>20/min); 4) white blood cell >12,000/mm3.

Three categories of operation time were defined as follows: 1) 0 to 90 minutes; 2) 90 to 180 minutes; and 3) 180 minutes and more.

The time required for the restoration of intestinal motility was categorized on the basis of the time required for the onset of normoactive intestinal sounds after the surgery: 1) 1 day; 2) 1 to 3 days; and 3) 3 days and more.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Definitive statistical data are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for numerical variables and as frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Numerical differences among groups were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test for numerical variables, and Pearson chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test. Risk coefficients were evaluated using logistic regression. The most significant risk factors were determined using multivariate regression analysis using the backward stepwise method. Alpha significance level with statistical analyses was set as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The subjects consisted of 66 male and 37 female patients with an average age of 57.2. Of the 103 surgery patients included in the research, 91.3% (n = 94) of the patients were malignant disease, whereas 8.7% (n = 9) were benign.

Operation types were distributed as follows: 52.4% resection (n = 54); 18.4% diversion (n = 19); 13.6% reconstruction-with different anastomosis from primary surgery (n = 14); 5.8% drainage (n = 6); 3.9% debridement (n = 4); 3.9% re-anastomosis-with recovery of first anostomosis (n = 4); and 1.9% lavage (n = 2). In addition, 53.4% of the patients (n = 55) had excessive small intestine manipulation.

Regarding operation time periods, 26.2% were shorter than 90 minutes; 42.7% lasted between 90 and 180 minutes, while 31.1% were longer than 180 minutes. The average opioid analgesics use period of the patients was 1.8 days (SD, 1.1). Of the patients, 46.6% did not have their nasogastric catheters removed for a week. Systemic inflammation was observed in 8.7% of the patients (n = 9).

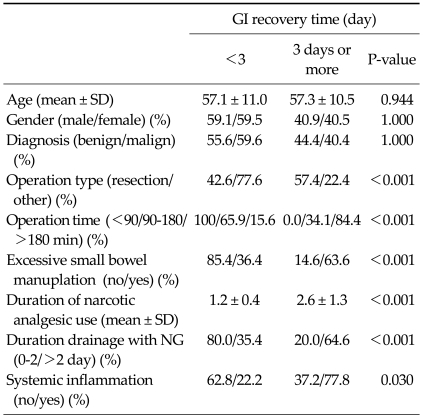

While gastrointestinal motility started in the first day for 24.3% of the patients (n = 25), it took 3 or more days for the remaining 40.8% of patients to regain motility. No statistically significant relationship was found between patient age and the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility (P = 0.944). No significant sex-related differences were found in the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility (P = 1.000). However, significant sex-related differences were detected in the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility (>3 days) in patients who had undergone intestinal resection, those with long operation periods, those with excessive intestinal manipulation, those with prolonged nasogastric catheter drainage, and those with systemic inflammation (systemic inflammation, P = 0.030; others P < 0.001). In addition, the period of opioid analgesic use in patients who recovered intestinal motility after 3 or more days was significantly higher than that in patients who recovered intestinal motility within 3 days (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors associated with gastrointestinal (GI) recovery time

NG, nasogastric.

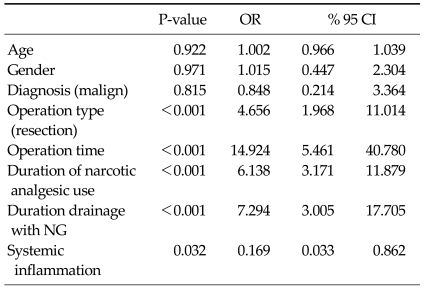

Regarding the factors that affected the restoration of gastrointestinal motility, resection operation type, longer operation period, longer opioid analgesics use period, longer nasogastric catheter use period, and the presence of systemic inflammation were shown to retard the return to normoactive bowel functions for 3 days or more (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of risk factors affecting gastrointestinal recovery time

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NG, nasogastric.

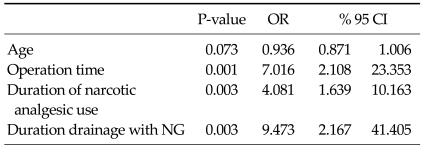

Under our multivariate logistic regression analysis model, in which risk factors were evaluated altogether, operation period, opioid analgesics use period, and nasogastric catheter use period were determined to be the most important factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors affecting gastrointestinal recovery time

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NG, nasogastric.

DISCUSSION

Although surgeons define postoperative ileus as the deceleration or arrest of intestinal motility in the postoperative period, it is not possible to find a perfect and standardized description in medical terminology. All the same, it is a well-known fact that the motility of the whole gastro-intestinal tract is affected following a surgical operation. While the small intestine recovers its motility in the first few postoperative hours, this period extends until 24 to 48 hours for the stomach, and until a couple of days for the colon. A functional definition of the entity "postoperative ileus" can be "the retardation of normal bowel activity to the uncoordinated motility of gastrointestinal system in this period." This state of retardation can be called as "postoperative ileus" if it goes beyond the third day. Although there are studies that refer to this condition that occurs secondarily to surgical operation as "primer ileus," the term "postoperative ileus" has been adopted by most clinicians due to the lack of an exact definition in literature [3,4].

As debatable as the definition of postoperative ileus may be, its pathogenesis is based on hypotheses. It is known that inhibitory neural factors are the most significant in the pathogenesis of postoperative ileus.Splanchnic nerves are considered to have an especially influential role in the pathogenesis. Also, in recent years, many studies have been conducted on the role of many neurotransmitters and inflammatory factors in postoperative ileus occurrence. In particular, nitric oxide, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and substance p have been proven to effect gastrointestinal tract motility, in terms of inhibition [2,5]. Through a study carried out on dogs, it has been shown that vasoactive intestinal peptide and nitric oxide cause the deceleration of the gastrointestinal system [6,7]. Additionally, it is a fact that opioids are the potential modulators of the central and peripheral neural system. It modulates its effects including the slowing of gastrointestinal motility, delay of gastric emptying, and increase of intraluminal pressure by µ receptors. On the other hand, the trauma resulting from the excessive intra-operative manipulation of the intestines is thought to possibly contribute to ileus occurrence by unfolding local inflammatory factors, although the number of studies dealing with the role of local inflammatory factors in postoperative ileus pathogenesis is quite few. In a study by Kallf et al., it has been shown that the paralytic response of the intestines to operative trauma is biphasic and that the intestines enter a longer immotile phase with the increase of local inflammatory factors on the tissue, following a short paralytic period. Consequently, in the light of all of these studies, there is a common view that postoperative ileus pathogenesis is a multi-factorial entity jointly composed by inhibitory, spinal, and sympathetic reflexes, neurotransmitters, local inflammatory factors, and humoral agents [1,5,8,9]. On the other hand, there are some risk fac

On the other hand, there are some risk factors that have been put forth by various studies regarding postoperative ileus, though its pathogenesis is not known exactly. In this regard, the most significant controllable risk factor is narcotic analgesics, which are frequently used during the postoperative period. It is known that opiates particularly postpone colonic transit on peripheral µ receptors. Many studies have shown that the paralytic interval extends in parallel with the morphine dosage and usage time [10,11]. For this reason, studies of recent years have particularly concentrated on selective opiate antagonists with the intention of moderating their negative effects on motility, without reducing the analgesic activity of narcotics. In our study, narcotic analgesic use significantly extended the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility (P < 0.001). In the future, the effective usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on patients who have undergone malignancy surgery constitutes a remarkable alternative, with respect to both its inflammatory activity and its ability to reduce the need for opiates.

On the other hand, intestinal trauma occurring secondarily to surgical manipulation during operation is another one of the risk factors for postoperative ileus. In addition to the fact that the dysmotility stemming from the surgical stress following laparotomy also affects the segments of gastrointestinal tract that are unmanipulated and remote from the surgical area, manipulations intra-operatively made by the hand of the surgeon have been proven to illicit a more concentrated immune and neural response in these segments by adding local trauma to surgical stress [12]. Regarding our research, when the surgical approach toward patients undergoing major abdominal attempts due to malignancy is quite radical, we can predict that excessive small intestine manipulation will increase to the same degree. In fact, in parallel with this prediction, our results also indicate that excessive small intestinal manipulation significantly extends the time required for the restoration of intestinal motility. One of the most interesting finding of our study is that the onset of gastrointestinal motility was significantly delayed after intestinal resection relative to other operation types. Many studies showed that intestinal manipulation resulted in the occurrence of local inflammatory factors and leukocyte recruitment. We deem the reason discovered to be against resection in our research to occur due to higher surgical intestinal manipulation concentration as a part of the relevant surgical technique.

In addition, it is reported that colonic motility was one of the major factors affecting the functional revival of the gastrointestinal tract [13]. Perhaps, the most important hypothesis in this study is that the colon acts similar to an "immune organ" and triggers an immune cascade that limits colonic transit time and coordinated motility following surgical trauma [9,14]. The case of postoperativeileus, in which the small intestine and colon share the dominant role, bears results that retard oral nutrition. Further, studies suggest that, in some cases, starting oral nutrition prematurely may have an adverse effect and contribute to the return of gastrointestinal dysmotility [1]. On the other hand, some authors have claimed that premature oral nutrition can be tolerated by 80% of patients and increases motility by stimulating gastrointestinal mucosa as a result of which can postoperative incidence be decreased. Although premature nutrition has been suggested to reduce not only postoperative ileus incidence, but also postoperative infections and hospital stay, since it significantly increases the incidence of anastomotic leakage [1], starting premature oral nutrition is still thought to find only a limited scope of application.

In addition to all of these factors, another risk factor in postoperative ileus etiology is the use of general anesthetic agents [15]. Nitrous oxide is particularly known to inhibit gastrointestinal motility. In the future, operation period should be handled as a risk factor in terms of postoperative ileus. Investigations regarding the relationship between the duration of exposure to general anesthetic agents and the postoperative ileus period have determined that as the duration of exposure to general anesthetic agents increases, the time required for the resumption of gastrointestinal motility is proportionally extended. Again, considering the radical resection rates applied in surgical attempts made for intra-abdominal malignant tumors, in addition to the excessive intestinal manipulation, the exposure time to the "inhibitory" effect of general anesthetic agent is often extended; thus, the fact that, especially after the resection of intra-abdominal malignant tumors, the postoperative paralytic period of the gastrointestinal tract extends to the same degree does not come as a surprise. The idea of applying thoracic epidural anesthesia in order to avoid this inhibition has recently gained popularity [1]. Again, research has shown that the incidence of postoperative ileus in the attempts made with epidural anesthesia significantly recedes, which has been explained by the intactness of vagal stimulation [1]. However, on this point, in contrast to all intra-abdominal attempts, in attempts made for malignant tumors, attention should be paid to the effective analysis of epidural anesthetic application due to the fact that the operation area is larger and the borders of resection cannot be predicted.

When it comes to intra-abdominal attempts, especially in order to avoid anastomose induced complications, oral intake is either prematurely or completely ceased. On this point, the role of drainage through nasogastric catheters is quite controversial. Large-scale studies [16,17] have suggested that the rates of pneumonia and atelectasis increase until oral nutrition resumes in patients in whom a nasogastric catheter is routinely placed. Although nasogastric catheter drainage has not been proven to contribute to intestinal revival during the postoperative period, and although it has been observed to increase atelectasis and fever incidences, some view it preferably in patients with severe dysmotility due to the fact that it reduces vomiting and aspiration risk related to vomiting [16]. One of the most interesting findings put forth in this study is that far from contributing to postoperative ileus treatment, longterm nasogastric drainage actually decelerates postoperative intestinal motility. In parallel with this conclusion, as long term nasogastric catheter use retards adaptation to oral nutrition and increases the tendency toward associated systemic diseases (especially pulmonary complications), we deem that it would be advantageous to avoid using it, except for in some certain cases. The study conducted by Gerald Moss in 2009 provides an example of cases in which simple nasogastric catheter use is avoided. In this study [18], a nasogastric catheter having 2 lumina, each of which enables stomach emptying and enteral feeding from the duodenum, was used and increased intestinal motility together with oral intolerance was achieved. Nonetheless, as previously discussed in the topic of starting nutrition prematurely, we think that certain attention needs to be paid especially to the matters of pulmonary complications and anastomosis leakage when the use of a double-lumen catheter is in question.

On the other side, it is obvious that the adopted surgical technique also plays a major role in the occurrence of postoperative ileus. We would like to highlight the roles of adopting laparoscopic and minimally invasive techniques for abdominal surgical attempts in the occurrence of postoperative ileus. Many studies suggest that the effect of laparoscopic intra-abdominal attempts on intestinal motility is far less than that of laparotomy. The minimization of the stimulation of inhibitory reflexes, intestinal manipulation, and surgical trauma during laparoscopic and minimally invasive [19] attempts results in reduced postoperative ileus incidence [2].

Having examined all risk factors, we would like to briefly discuss the treatment approaches to consider in cases of postoperative ileus. Considering the pharmacological agents that have been previously used for the treatment of postoperative ileus, various agents ranging from macrolide antibiotic erythromycin, which is a motilin agonist at the same time, to metoclopramide, which is not only a dopaminergic D2 but also a serotoninergic 5HT3 antagonist, and prostigmin, which is a reversible cholinesterase inhibitor, have been tested, but no agent has been suggested to achieve effectiveness individually. Often questioned in recent years, alvimopan, which is a peripheral ? receptor antagonist, offers promising results. In the study carried out by Delaney et al. [20] on 1212 patients with colonic resection, it was shown that alvimopan use significantly shortened the time required for the restoration of gastrointestinal motility. Again, in a study carried out by Ludwig on 654 patients who underwent both small intestinal and colonic resection, it was shown that the group using alvimopan regained gastrointestinal motility earlier, tolerated oral nutrition in a shorter time, and started defecation earlier [21].

Few published studies specifically address postoperative occurrence rates and risk factors of postoperative ileus following surgical interventions due to intra-abdominal malignant tumors. From this point of view, it is possible to claim that the results accompanying this study are remarkable. The most significant finding of this study is that, in postoperative ileus cases, the timing of restoration of gastrointestinal motility is not affected by the underlying condition, whether malignant or benign; rather, it is affected by the type of surgical intervention, particularly, if it involves intestinal resection. From this point on, regardless of the malignity or benignity of the intra-abdominal pathology, we consider it necessary to pay utmost attention to postoperative ileus occurrence in patients who undergo radical resection, to abstain from narcotic analgesics and long term nasogastric catheter use as much as possible after surgical interventions made due to malignant tumors, to avoid excessive small intestinal manipulation, and to adopt a quick and effective technique for surgery by taking the inhibitory effect of the general anesthetic agent that has been imposed.

Like extended postoperative ileus cases, malignant diseases also bring along various associated problems. Cost effectiveness can be counted among these problems. In our study, we concluded that limited small bowel manipulation in intra-abdominal malignant tumors is another way of improving cost effectiveness. Our study was also confirmed that unnecessary analgesics use in patients who have no pain with non-steroid anti-inflamatuar drugs, indirectly results in cost increase by causing extended ileus. Moreover, we deduced that prolonged nasogastric catheter use has an indirect negative effect on cost by damaging the pathophysiological balance of intestinal motility and increasing the postoperative hospitalization period.

Conventional treatment for postoperative ileus is based on a multimodal approach [2,22]. Considering that an exact treatment for postoperative ileus has not yet been established, and in the light of the risk factors mentioned above, we regard that prevention of postoperative ileus is the most effective way of coping with intestinal dysmotility.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Lubawski J, Saclarides T. Postoperative ileus: strategies for reduction. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:913–917. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holte K, Kehlet H. Postoperative ileus: a preventable event. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1480–1493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baig MK, Wexner SD. Postoperative ileus: a review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:516–526. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingston EH, Passaro EP., Jr Postoperative ileus. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:121–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01537233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in postoperative intestinal smooth muscle dysfunction in rodents. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:316–327. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen JJ, Caropreso DK, Hemann LL, Hinkhouse M, Conklin JL, Ephgrave KS. Pathophysiology of adynamic ileus. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:731–737. doi: 10.1023/a:1018847626936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen JJ, Ephgrave KS, Caropreso DK. Gastrointestinal myoelectric activity during endotoxemia. Am J Surg. 1996;171:596–599. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(96)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Surgical manipulation of the gut elicits an intestinal muscularis inflammatory response resulting in postsurgical ileus. Ann Surg. 1998;228:652–663. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199811000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalff JC, Carlos TM, Schraut WH, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Surgically induced leukocytic infiltrates within the rat intestinal muscularis mediate postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:378–387. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman PN, Krevsky B, Malmud LS, Maurer AH, Somers MB, Siegel JA, et al. Role of opiate receptors in the regulation of colonic transit. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1351–1356. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(88)90673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cali RL, Meade PG, Swanson MS, Freeman C. Effect of Morphine and incision length on bowel function after colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:163–168. doi: 10.1007/BF02236975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Türler A, Schnurr C, Nakao A, Tögel S, Moore BA, Murase N, et al. Endogenous endotoxin participates in causing a panenteric inflammatory ileus after colonic surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:734–744. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000255595.98041.6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Türler A, Moore BA, Pezzone MA, Overhaus M, Kalff JC, Bauer AJ. Colonic postoperative inflammatory ileus in the rat. Ann Surg. 2002;236:56–66. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalff JC, Hierholzer C, Tsukada K, Billiar TR, Bauer AJ. Hemorrhagic shock results in intestinal muscularis intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) expression, neutrophil infiltration, and smooth muscle dysfunction. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999;119:89–93. doi: 10.1007/s004020050363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaya T, Köylüoğlu G, Gürsoy S, Kunt N, Kafali H, Soydan AS. Effects of propofol and tramadol on cholinergic receptor-mediated responses of the isolated rat ileum. Turkiye Kli J Med Sci. 2004;24:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson MD, Walsh RM. Current therapies to shorten postoperative ileus. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76:641–648. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76a.09051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheatham ML, Chapman WC, Key SP, Sawyers JL. A meta-analysis of selective versus routine nasogastric decompression after elective laparotomy. Ann Surg. 1995;221:469–476. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199505000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss G. The etiology and prevention of feeding intolerance paralytic ileus--revisiting an old concept. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2009;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holte K, Kehlet H. Prevention of postoperative ileus. Minerva Anestesiol. 2002;68:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delaney CP, Wolff BG, Viscusi ER, Senagore AJ, Fort JG, Du W, et al. Alvimopan, for postoperative ileus following bowel resection: a pooled analysis of phase III studies. Ann Surg. 2007;245:355–363. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000232538.72458.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludwig K, Enker WE, Delaney CP, Wolff BG, Du W, Fort JG, et al. Gastrointestinal tract recovery in patients undergoing bowel resection: results of a randomized trial of alvimopan and placebo with a standardized accelerated postoperative care pathway. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1098–1105. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MJ, Min GE, Yoo KH, Chang SG, Jeon SH. Risk factors for postoperative ileus after urologic laparoscopic surgery. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;80:384–389. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.80.6.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]