Abstract

A 70-year-old man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma developed progressive liver metastases after 8 weeks of treatment with the multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sunitinib. He then participated in the phase III placebo-controlled clinical trial of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus, initially randomized to placebo (but had disease progression after 3 months) and crossed over to everolimus at time of unblinding. The patient had stable disease after 8 weeks (two cycles) of everolimus that was maintained until 28 months of therapy, at which time the patient had achieved a partial response. This case illustrates the potential for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, a malignancy with historically poor prognosis, to derive long-term benefit from everolimus when used in a manner consistent with its approved indication (after TKI therapy with sunitinib or sorafenib).

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, Kidney cancer, Everolimus, mTOR, Sunitinib, Metastatic

Introduction

Patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) have historically had a universally poor prognosis given the inability of systemic chemotherapy and immunotherapy to alter the natural history of the disease in most cases. In recent years, there have been a series of phase III randomized trials showing benefit for targeted drugs, namely the small-molecule multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) sorafenib [1], sunitinib [2], and pazopanib [3] and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors temsirolimus [4] and everolimus [5]. The oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus demonstrated a significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) versus placebo in the phase III RECORD-1 (REnal Cell cancer treatment with Oral RAD001 given Daily) trial (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00410124), in which clear-cell mRCC patients progressing within 6 months of discontinuing sorafenib and/or sunitinib were randomized to receive best supportive care in conjunction with everolimus 10 mg/day or placebo [5]. Per disease status assessment by independent central review, median PFS was 4.9 months with everolimus versus 1.9 months with placebo, translating into a 67% (P < 0.0001) reduction in the risk of progression or death. Stable disease was documented in 67% of everolimus recipients (with a 2% partial response rate) versus 32% of placebo recipients [5, 6].

Herein, we describe a case of a sunitinib-pretreated participant in RECORD-1 with prolonged stable disease, who went on to achieve a partial response after 28 months of therapy.

Case report

A 70-year-old man with a medical history significant for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and rheumatoid arthritis presented to Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) for the medical management of recently diagnosed mRCC. He had undergone a left radical nephrectomy for a T3 N0 M0 clear-cell RCC. After a 3-year disease-free interval, he had developed recurrent disease in the lungs. He underwent metastasectomy of two solitary lung nodules, both showing clear-cell histology. After a 1-year disease-free interval, he developed recurrent disease in the liver. He received sunitinib but had progressive liver metastases after 8 weeks of treatment.

The patient was enrolled into the RECORD-1 randomized phase III trial of everolimus versus placebo in conjunction with best supportive care (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00410124) under informed consent. Baseline characteristics included a Karnofsky Performance Status of 90% and a favorable MSKCC risk group. He progressed after three cycles of therapy, each of which was defined as 28 days of treatment. Unblinding revealed that the patient was receiving placebo and, as permitted per the protocol, he crossed over to receive oral everolimus 10 mg daily. Response was assessed with CT scans at the initial screening and repeated every 8 weeks for the first 2 years and every 12 weeks for the remainder of the study. Using RECIST to classify treatment responses, the patient achieved stable disease after 8 weeks (two cycles) of treatment. Stable disease persisted until cycle 28 when he achieved a partial response (Figs. 1 and 2), with regression in liver metastases. Partial response persisted for 9 months, at which time treatment was discontinued due to grade 3 transaminitis that was likely secondary to alcohol consumption. No grade 3 or 4 toxicities occurred previously over the course of treatment. He resumed off-protocol everolimus after the cessation of alcohol use and resultant resolution of the transaminitis and remains on treatment as of the time of this writing. To date, the patient has received 32 months of treatment on the clinical trial plus 8 months of off-protocol treatment for a total of 40 months of everolimus treatment.

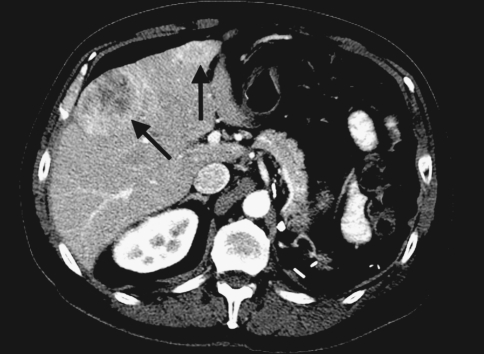

Fig. 1.

Baseline scan shows large heterogenous hepatic mass and a smaller enhancing mass (arrows)

Fig. 2.

Scan shows decrease in size and necrosis of hepatic masses on the follow-up study 30 months later (arrows)

Toxicities during the early course of treatment included grade 1 rash, fatigue, stomatitis, and ankle swelling. The most notable toxicity later in the course of treatment (after 18 months) was grade 2 hypertriglyceridemia. This led to an increase in the patient’s statin drug dose.

Discussion

The past decade marked a rapidly evolving era for the treatment of mRCC given the documented benefit of oral targeted therapy with the multitargeted TKIs sunitinib and sorafenib for this highly chemotherapy-resistant, poor-prognosis malignancy. Immunotherapy has served an important role, despite conferring limited benefit and generally high toxicity. Patients requiring discontinuation of these agents because of disease progression or treatment-related toxicity quickly surfaced as a new population with an unmet medical need. Based on the RECORD-1 experience [5], everolimus was granted U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of mRCC after failure of prior sunitinib and/or sorafenib. Everolimus has since been incorporated into clinical practice guidelines (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network [7], European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [8]), providing a much needed therapeutic option for use in community-based practice.

A recently presented sub-analysis of RECORD-1 focused on participants aged ≥70 years demonstrated that the prolonged PFS benefit and tolerability of everolimus are maintained in elderly patients, despite some adverse events occurring more frequently than in the overall population [9]. The elderly patient described here, with two separate episodes of recurrent clear-cell RCC and progressive disease on sunitinib and while on the placebo arm of the RECORD-1 trial, converted from stable disease to a partial response after nearly 3 years of everolimus therapy. Although most of the clinical benefit of everolimus is in the form of stable disease, a small number of partial responses were seen among everolimus recipients in RECORD-1 [5, 6] and the prior phase II clinical trial in mRCC [10]. These findings are consistent with that from a retrospective review of patients with intermediate or poor-prognosis mRCC treated with temsirolimus after failure of a VEGF-targeted therapy in a compassionate-use program. The majority of patients achieved stable disease; comparatively few patients achieved a partial response [11].

The patient described here tolerated everolimus therapy well, as illustrated by his long-term use. Although treatment was discontinued during the clinical trial because of transaminitis, this event was considered to be related to the patient’s alcohol consumption and has not recurred since reinstitution of everolimus. Transaminase elevations were reported more frequently with everolimus versus placebo in RECORD-1, with raised aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in 21 and 18% of everolimus recipients, respectively (7 and 4%, respectively, with placebo), which were limited to grade 1/2 severity except for grade 3 AST and ALT elevations in 1 patient each [5]. In RECORD-1, hypercholesterolemia was the second most common laboratory abnormality (after anemia), reported in 76% of everolimus recipients (including 3% grade 3 incidence) versus 32% of placebo recipients. Stomatitis, rash, fatigue, and asthenia were the most common adverse events reported during everolimus therapy in RECORD-1, with grade 3/4 incidences <5% for these and other treatment-related adverse events (primarily gastrointestinal issues).

This example of everolimus-associated prolonged disease stabilization (and subsequent partial response) in a sunitinib-pretreated patient represents the successful application of approved targeted agents in this setting.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing, copyediting, and editorial assistance (grammatical and stylistic assistance, preparing references) was provided by Laurie Orloski, PharmD and Scientific Connexions, and supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

References

- 1.Escudier B, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg CN, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in treatment-naive and cytokine-pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s (suppl; abstr 5021).

- 4.Hudes G, et al. Global ARCC Trial. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Motzer RJ, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116(118). doi:10.1002/cncr.25219. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Motzer RJ, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: kidney cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:618–630. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reijke TM, et al. EORTC-GU group expert opinion on metastatic renal cell cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutson TE, et al. Everolimus in elderly patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an exploratory analysis of the RECORD-1 study. Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, March 5–7, 2010, San Francisco, CA. Abstract and Poster 362.

- 10.Amato RJ, et al. A phase 2 study with a daily regimen of the oral mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) in patients with metastatic clear cell renal cell cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:2438–2446. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackenzie MJ, et al. Temsirolimus in VEGF-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq320. http://annonc.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/06/30/annonc.mdq320.full.pdf+html. [DOI] [PubMed]