Abstract

The growth of Escherichia coli DH5α recombinants producing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) (DH5αEPA+) and those not producing EPA (DH5αEPA–) was compared in the presence of hydrophilic or hydrophobic growth inhibitors. The minimal inhibitory concentrations of hydrophilic inhibitors such as reactive oxygen species and antibiotics were higher for DH5αEPA+ than for DH5αEPA–, and vice versa for hydrophobic inhibitors such as protonophores and radical generators. E. coli DH5α with higher levels of EPA became more resistant to ethanol. The cell surface hydrophobicity of DH5αEPA+ was higher than that of DH5αEPA–, suggesting that EPA may operate as a structural constituent in the cell membrane to affect the entry and efflux of hydrophilic and hydrophobic inhibitors.

Keywords: Cell hydrophobicity, eicosapentaenoic acid, membrane-shielding effect, minimal inhibitory concentration, organic solvent.

INTRODUCTION

The cell membrane-shielding effect of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs), such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in bacteria is thought to occur because a more hydrophobic interface is formed between the bilayers of cell membrane phospholipids acylated with a LC-PUFA in combination with a medium-chain saturated or mono-unsaturated fatty acid, and this interface shields the entry of hydrophilic compounds [1, 2]. We showed that Escherichia coli cells that had been transformed with EPA biosynthesis pfa genes [3, 4], and naturally EPA-producing Shewanella marinintestina IK-1 (IK-1) have the potential to prevent the entry of H2O2 molecules through the cell membrane [1]. When these bacterial cells producing EPA were treated with H2O2, intracellular concentrations of H2O2 in these cells were maintained at levels lower than those in their reference cells producing no EPA [1, 4]. Thus, the generation of protein carbonyls was suppressed to a lesser extent in cells with EPA than in cells without EPA. This has been regarded as a novel antioxidative function of PUFAs such as EPA and DHA.

In a previous study [5], we used IK-1 and its EPA-deficient mutant IK-1Δ8 (IK-1Δ8) to show that membrane EPA is involved in the increased hydrophobicity of bacterial cells and that it affects the entry of hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. Briefly, IK-1 and IK-1Δ8 were grown on microtiter plates at 20 °C in nutrient media that contained various types of growth inhibitors. The minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of water-soluble H2O2, tert-butyl hydroxyl peroxide (tert-BHP) and antibiotics were higher for IK-1 than for IK-1Δ8. In contrast, IK-1 was less resistant than IK-1Δ8 to two hydrophobic oxidative phosphorylation uncouplers, carbonyl cyanide m-chloro phenyl hydrazone (CCCP) and N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. The hydrophobicity of the IK-1 and IK-1Δ8 cells determined using the bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon method [6] was higher for IK-1 cells, which contained EPA at approximately 10% of total fatty acids, compared with their counterparts with no EPA. From these results, we concluded that the high hydrophobicity of IK-1 cells can be attributed to the presence of membrane EPA, which shields the entry of hydrophilic membrane-diffusible compounds, and that hydrophobic compounds such as CCCP and N,N'-dicyclohexylcar-bodiimide diffuse more effectively in the membranes of IK-1, where these hydrophobic compounds can exhibit their inhibitory activities, than in the membranes of IK-1Δ8. However, the membrane-shielding functions of LC-PUFAs have not been reported for bacteria other than IK-1 and E. coli recombinants producing EPA or DHA.

In this study, we used EPA-producing and EPA-not producing E. coli DH5α recombinants to further investigate the applicability of the membrane-shielding effects of EPA against various kinds of hydrophilic and hydrophobic growth inhibitors, such as reactive oxygen species (H2O2 and tert-BHP), hydrophilic and hydrophobic radical generators (2,2'-azobis-(2-amidopropane)hydrochloride (AAPH) and 2,2'-azobis-(2,4-dimethyl)valeronitrile (AMVN), respectively), hydrophilic antibiotics (ampicillin sodium, kanamycin sulfate and streptomycin sulfate), an uncoupling reagent in oxidative phosphorylation (CCCP) and organic solvent (ethanol). To evaluate the relation between hydrophobicity of each bacterial cell and the cellular content of EPA, we used the bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon method [5,6] and tested E. coli recombinants with various levels of EPA.

The E. coli strain DH5α was used as host. Recombinant cells of E. coli DH5α (see below) were cultivated normally at 20°C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium with shaking at 150 rpm in the presence of 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol for two days. Bacterial strains and vectors used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and Vectors Used in this Study

| Strain/tdlasmid/Cosmid | Relevant Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | deoR, endA1, gyrA96, hsdR17(rK– mK+), recA1 phoA, relA1, thi-1, Δ(lac ZYA-argF) U169φ80dlacZΔM15, F–, λ–, supE44 | Takara Bioa |

| Plasmid/Cosmidb | ||

| pSTV28 | Low-copy-number cloning vector, Cmr | Takara Bio |

| pSTV::pfaE | pSTV28 carrying pfaE from S.pneumatophoruse SCRC-2738 | [7] |

| pNEB139 | High-copy-number expression vector, Ampr | New England Biolabsc |

| pEPAΔ1,3,4,9 | pNEB carrying pfaA–E from S.pneumatophori SCRC-2738 | [9] |

| Stratagened | ||

| pWE15 | Cosmid expression vector, Kmr, Ampr | Takara Bio |

| pEPAΔ1,2,3 | pWE15 carrying an EPA gene cluster that lacks pfaE from S. pneumatophori SCRC-2738 | [3] |

Takara Bio Inc., Tokyo, Japan.

Abbreviations of antibiotics: Km, kanamycin; Amp, ampicillin; and Cm, chloramphenicol.

New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA.

Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Unless otherwise stated, E. coli DH5α was transformed with pEPAΔ1,2,3, which is a cosmid clone that includes four (pfaA, pfaB, pfaC and pfaD) of the five genes essential for the biosynthesis of EPA and an additional two open reading frames unnecessary for EPA biosynthesis from Shewanella pneumatophori SCRC-2738 and a pSTV28 plasmid vector carrying pfaE encoding phosphopantetheinyl transferase (pSTV::pfaE); pfaE is the fifth gene needed for EPA biosynthesis from the same bacterium ([7] and Table 1). The host E. coli DH5α cells that had been transformed with these two vectors produced EPA at a level of 10% of total fatty acids, when growth at 20 ºC [3]. The E. coli DH5α recombinant reference strain, which has no ability to produce EPA, was transformed with pEPAΔ1,2,3 and empty pSTV28. E. coli DH5α with and without EPA were designated DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA–, respectively. To increase the content of EPA, E. coli DH5α was transformed with pEPAΔ1,3,4,9, which is a pNEB clone containing pfaA, pfaB, pfaC, pfaD and pfaE but no unnecessary open reading frames from S. pneumatophori SCRC-2738 [8]. Levels of EPA of this recombinant, which was grown at 20 °C, were approximately 20% of total fatty acids [9].

To perform growth inhibition tests, 96-well microtiter plates (0.35 ml per well; Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) were used, as described previously [5]. Briefly, E. coli DH5α recombinant cells were grown for 48 h at 20 °C. One hundred microliters of these cultures [1.0 at 600 nm (OD600)] was diluted with 100 ml of medium. To 180 μl of the diluted cultures, 20 μl of aqueous solutions containing various concentrations of growth inhibitors were added. AAPH and AMVN were used as hydrophilic and hydrophobic radical generators, respectively. CCCP was used as a hydrophobic proton conductor. To dissolve AMVN and CCCP, absolute ethanol was used. For AMVN and CCCP, 2 μl aliquots were mixed with 198 μl of the diluted cultures. After inoculation, the plates were incubated for four days at 20 °C. Growth of cells was monitored visually and the bottom face of the microtiter plates was scanned with a scanner.

To cultivate E. coli recombinants in LB medium containing ethanol, test tubes with silicon caps were used to prevent organic solvent from volatizing. The OD600 of E. coli DH5αEPA+ and E. coli DH5αEPA– cells precultivated in LB medium, as described above, was adjusted to 1.0 with the same medium. One hundred microliter aliquots of the precultures were mixed with 100 ml of the medium. Ten milliliters of the cultures were transferred to test tubes. To these cultures, ethanol (0, 300, 500, 600, and 700 μl) was added and then they were cultivated with shaking at 150 rpm at 20 °C. It is known that a strain of E. coli grows weekly in ethanol concentrations above 6% by volume [10].

The hydrophobicities of cells of DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA– were estimated by the bacterial adhesion to hydro-carbon method [6], as described previously [5]. The hydrophobicity was expressed as a percentage of the adherence of cells to hexadecane and calculated as 100 × (OD600 of the aqueous phase after vortex/OD600 of the initial cell suspension).

Fatty acids of cells were analyzed as methyl esters by gas–liquid chromatography, as previously described [7].

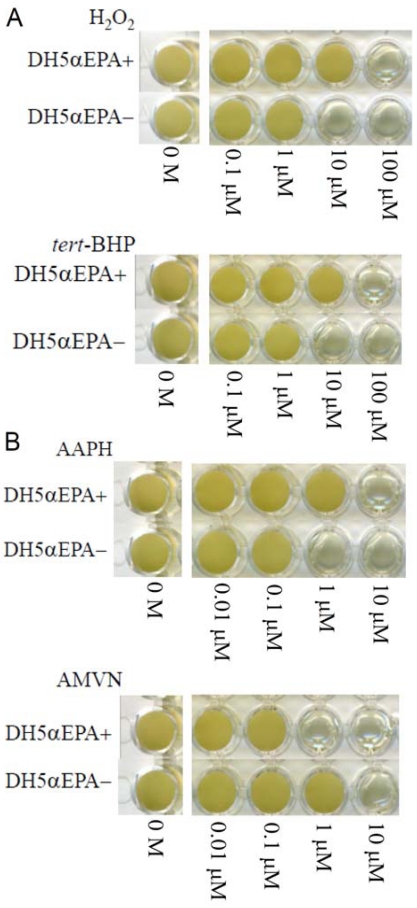

The MICs of H2O2 and tert-BHP were both 100 μM for DH5αEPA+ and were both 10 μM for DH5αEPA– (Fig. 1A). The MICs of AAPH and AMVN were 10 μM and 1 μM, respectively, for DH5αEPA+ and were 1 μM and 10 μM, respectively, for DH5αEPA– (Fig. 1B). The MIC of CCCP was 1 mM and 10 mM for DH5αEPA+ and for DH5αEPA–, respectively. AMVN and CCCP are water-insoluble and ethanol-soluble compounds. The final concentration of ethanol in the culture medium was 1% (v/v), and this concentration of ethanol had no effect on the growth of DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA–. DH5αEPA+ was much more resistant to the three hydrophilic compounds, H2O2, tert-BHP and AAPH, than was DH5αEPA–. The same tendency was observed, when cells of DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA– were treated with three types of water-soluble antibiotics including ampicillin sodium, kanamycin sulfate and streptomycin sulfate. However, DH5αEPA+ was more sensitive to the hydrophobic AMVN and CCCP than was DH5αEPA–. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Fig. (1).

Effects of concentration of various compounds on the growth of E. coli DH5α with EPA (DH5αEPA+) and that with no EPA (DH5αEPA–). (A) reactive oxygen species; (B) radical generators. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; tert-BHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide; AAPH, 2,2΄-azobis-(2-amidopropane)hydrochloride; and AMVN, 2,2΄-azobis-(2,4-dimethyl)valeronitrile. Cells were grown for 4 days at 20 °C.

Table 2.

Effects of Various Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Compounds on the Growth of Cells of E. coli DH5α Recombinants with EPA (DH5αEPA+) and without EPA (DH5αEPA–)

| MICs of Various Compoundsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent | DH5αEPA+ | DH5αEPA– | |

| Reactive oxygen species (MW) | |||

| H2O2 (34.0) | Water | 100 µM | 10 µM |

| tert-BHP (90.1) | Water | 100 µM | 10 µM |

| Radical generator | |||

| AAPH (271.19) | Water | 10 µM | 1 µM |

| AMVN (248.37) | 1% Ethanolb | 1 µM | 10 µM |

| Antibiotics | |||

| Ampicillin sodium (371.4) | Water | >500 µg/ml | 500 µg/ml |

| Kanamycin sulfate (582.6) | Water | >500 µg/ml | 500 µg/ml |

| Streptomycin sulfate (1457.4) | Water | 3 µg/ml | 0.3 µg/ml |

| Oxidative phosphorylation uncouplers | |||

| CCCP (204.1) | 1% Ethanol | 1 mM | 10 mM |

MW, molecular weight; MICs, minimal inhibitory concentrations; AAPH, 2,2΄-azobis-(2-amidopropane)hydrochloride; AMVN, 2,2΄-azobis-(2,4-dimethyl)valeronitrile tert-BHP, tert-butyl hydroxyl peroxide; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chloro phenyl hydrazone.

Final concentration.

DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA– cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of ethanol at 20 ºC. DH5αEPA+ cells grew much better in approximately 5% ethanol than DH5αEPA– for seven days at 20 ºC and the former weakly grew even in approximately 6% ethanol but the latter did not under the same conditions. No growth was observed in both strains in 7% ethanol. When E. coli DH5α carrying pNEBΔ1,3,4,9 was grown at 20 ºC, cells grew well in approximately 5% and 6% ethanol than DH5αEPA+ cells and did not grow in 7% ethanol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of Various Concentrations of Ethanol on the Growth of Cells of E. coli DH5α Recombinants Producing Various Levels of EPA

| OD600 of Cultures Containing Ethanol at Approximatelya | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 7% | |

| E. coli DH5α cellsb carrying | |||||

| pEPAΔ1,3,4,9 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | NGc |

| pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaEd | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | NG |

| pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTVd | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | NG | NG |

Values are average ± standard deviation of three independent measurements.

Cells were grown for 7 days at 20 °C.

No growth detected.

pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaE and pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV are DH5αEPA+ and DH5αEPA–, respectively.

The bacterial cell surface hydrophobicity of various E. coli DH5α recombinants was expressed as the percentage adhesion of bacterial cells to water measured using the bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon method. To change the cellular level of EPA, E. coli DH5α cells were transformed by different combinations of vectors carrying pfa genes and grown at different temperatures. Levels of EPA of E. coli DH5α cells that had been transformed with pEPAΔ1,2,3 plus pSTV28::pfaE were 16% ± 1%, 11% ± 1% and 0% of the total fatty acids at 15, 20 and 30 °C, respectively. The cells transformed with pEPAΔ1,2,3 plus pSTV28 had no EPA (Table 4). When E. coli DH5α cells were transformed with pEPAΔ1,3,4,9 and grown at 20 ºC, the EPA level was 21% ± 2%. DHA5α cells with higher levels of EPA had higher cell hydrophobicity (lower values; Table 4). The lowest hydrophobicity (highest value) was 98% for the two types of E. coli DH5α cells with no EPA: those grown at 30 °C with pEPAΔ1,2,3 plus pSTV28::pfaE and those grown at 20 °C with pEPAΔ1,2,3 plus empty pSTV28.

Table 4.

Effects of the EPA Content on the Cell Surface Hydrophobicity of Various E. coli DH5α Recombinants Grown at 15, 20 or 30°C

| E. coli DH5α Carrying | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEPAΔ1,3,4,9 | pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaEc | pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaE | pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTVc | pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaE | |

| Growth temp. °C | 20 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 30 |

| EPA content (%)a | 21 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | N.D.d | N.D. |

| Hydrophobicitya,b | 87 ± 2 | 93 ± 5 | 96 ± 1 | 98 ± 0 | 98 ± 0 |

Values are average ± standard deviation of three independent measurements.

Hydrophobicity is expressed as the percentage adhesion of bacterial cells to water; lower values show higher hydrophobicity of cells.

pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV::pfaE and pEPAΔ1,2,3 + pSTV are DH5ΔEPA+ and DH5ΔEPA–, respectively.

Not detected.

The present results using E. coli recombinant cells producing EPA and those not producing EPA were almost the same as the results using a native EPA-producing strain S. marinintestina IK-1 and its EPA-deficient mutant IK-1Δ8 in terms of the resistance and sensitivity to hydrophilic and hydrophobic growth inhibitors [5]. Considering that the EPA content of DH5αEPA+ (a recombinant carrying pEPAΔ1,2,3 plus pSTV::pfaE) is approximately 10% of total fatty acids, these results can also be explained by the hydrophobicity of the EPA-containing cell membranes. The converse results using hydrophobic compounds as substrate, such as AMVN and CCCP (Fig. 1B and Table 2), can be also explained by the increased cell surface hydrophobicity. AMVN and CCCP tend to accumulate in the more hydrophobic cell membrane of DH5αEPA+, where more radicals are produced by AMVN and oxidative phosphorylation is inhibited more effectively by CCCP. Since hydrophilic antibiotics with molecular weights less than about 600 pass nonspecifically through porin channels on the outer membrane and not by diffusion [11], streptomycin sulfate, with a molecular weight of 1457.4, could be shielded at the outer and inner membranes, although we have not confirmed the distribution of EPA in both the membranes.

Higher levels of EPA in E. coli DH5αrecombinants cells provided higher hydrophobicity of the cells (Table 4). As the relieving effects of EPA on H2O2-induced growth inhibition increased with cellular levels of EPA [9], it is considered that higher MICs of various hydrophilic growth inhibitors would be obtained for cells with higher cell surface hydrophobicity and vice versa for cells with lower cell surface hydrophobicity. Therefore, the function of EPA in recombinant E. coli DH5α cells would be based on the membrane-shielding effects of EPA against hydrophilic compounds and this function of EPA would not apply to hydrophobic compounds, which tend to accumulate in the membranes. In addition to these physical effects of EPA, EPA may have specific interactions with proteins involved in membrane transport, such as Omp, TolC and Acr proteins [5].

E. coli DH5αEPA+ grew in the presence of higher concentrations of ethanol, compared to E. coli DH5αEPA– (Table 3). In general, the organic solvent tolerance of E. coli arises mainly from the AcrAB–TolC and AcrEF–TolC efflux pumps [11]. The finding that the lack of EPA leads to the decreased concentrations of a tentative TolC family protein and decreased growth rates in the EPA-deficient mutant of Shewanella livingstonensis Ac10 [12] supports the involvement of TolC protein in the increased efflux activity of organic solvents in DH5αEPA+. However, the relationship between EPA and Acr proteins has not been elucidated. Ethanol is only slightly less polar than water and is freely permeable across bacterial membranes [10] and affects, in addition to proteins on the cell surface and within the membranes, cytoplasmic enzymes and functions [13]. Thus, the membrane-shielding effects of EPA may primarily cause the resistant mechanism of DH5αEPA+ against ethanol. This is supported by the findings that an E. coli mar mutant deficient in multiple antibiotics resistance and an acrAB mutant display the same tolerance to simple alcohols as their parents [14].

It is worth noting that there is a close relation between an improvement of organic solvent tolerance and resistance to multiple antibiotics in E. coli [15]. This is in line with the finding that the presence of EPA in E. coli confers resistance against antibiotics (Table 2) and ethanol (Table 3). It is conceivable that the common efflux pumping systems are involved in the resistance against antibiotics and organic solvents in E. coli systems including DH5αEPA+.

Based on the present and previous studies [1-5, 9], it has become evident that bacterial EPA (and probably DHA) has functions other than that to modulate the membrane fluidity in the cold adaptation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

pEPAΔ1,2,3, pSTV::pfaE and pEPAΔ1,3,4,9 were kindly provided by Sagami Chemical Research Center, Ayase 252-1193, Japan. This work was partly supported by the National Institute of Polar Research and by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research ((C) no. 22570130) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nishida T, Yano Y, Morita N, Okuyama H. The antioxidative function of eicosapentaenoic acid in a marine bacterium, Shewanella marinintestina IK-1. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4212–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okuyama H, Orikasa Y, Nishida T. Significance of antioxidative function of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in marine microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:570–4. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02256-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishida T, Orikasa Y, Ito Y, et al. Escherichia coli engineered to produce eicosapentaenoic acid becomes resistant against oxidative damages. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2731–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishida T, Orikasa Y, Watanabe K, Okuyama H. The cell membrane-shielding function of eicosapentaenoic acid for Escherichia coli against exogenously added hydrogen peroxide. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6690–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishida T, Hori R, Morita N, Okuyama H. Membrane eicosapentaenoic acid is involved in the hydrophobicity of bacterial cells and affects the entry of hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;306:91–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg M, Gutnick D, Rosenberg E. Adherence of bacteria to hydrocarbons: a simple method for measuring cell-surface hydrophobicity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;9:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orikasa Y, Nishida T, Hase A, et al. A phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene essential for biosynthesis of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from Moritella marina strain MP-1. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4423–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orikasa Y, Yamada A, Yu R, et al. Characterization of the eicosapentaenoic acid biosynthesis gene cluster from Shewanella sp. strain SCRC-2738. Cell Mol Biol. 2004;50:625–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishida T, Orikasa Y, Watanabe K. Benning C, Ohlrogge J, et al. Current advances in the biochemistry and cell biology of plant lipids. Salt Lake City, UT: Aardvark Global Pub. Co; 2007. Evaluation of the antioxidative effects of eicosapentaenoic acid by growth inhibition testing on plates using Escherichia coli transformed with pfa genes; pp. 116–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram LO. Ethanol tolerance in bacteria. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1990;9:305–19. doi: 10.3109/07388558909036741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1990;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawamoto J, Kurihara T, Yamamoto K, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid plays a beneficial role in membrane organization and cell division of a cold-adapted bacterium, Shewanella livingstonensis Ac10. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:632–40. doi: 10.1128/JB.00881-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman YA, Ingram LO. Mechanism of ethanol inhibition of fermentation in Zymomonas mobilis CP4. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:173–80. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.173-180.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ankarloo J, Wikman S, Nicholls IA. Escherichia coli mar and acrAB mutants display no tolerance to simple alcohols. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:1403–12. doi: 10.3390/ijms11041403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aono R, Kobayashi M, Nakajima H, Kobayashi H. A close correlation between improvement of organic solvent tolerance levels and alteration of resistance toward low levels of multiple antibiotics in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:213–8. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]