Abstract

Advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is associated with profound immunodeficiency, including changes in T regulatory cells (Tregs). We determined the pattern of expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), CD25, CD27 and CD127 and showed that the frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells was increased in CLL patients (12% versus 8% in controls). This increase was seen only in advanced disease, with selective expansion of FoxP3-expressing cells in the CD4+CD25low population, whereas the number of CD4+CD25highFoxP3+ cells was unchanged. CD4+CD25low cells showed reduced expression of CD127 and increased CD27, and this regulatory phenotype was also seen on all CD4 T cells subsets in CLL patients, irrespective of CD25 or FoxP3 expression. Incubation of CD4+ T cells with primary CLL tumours led to a sixfold increase in the expression of FoxP3 in CD4+CD25- T cells. Patients undergoing treatment with fludarabine demonstrated a transient increase in the percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells, but this reduced to normal levels post-treatment. This work demonstrates that patients with CLL exhibit a systemic T cell dysregulation leading to the accumulation of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells. This appears to be driven by interaction with malignant cells, and increased understanding of the mechanisms that are involved could provide novel avenues for treatment.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, fludarabine, immunomodulation, T regulatory cells

Introduction

B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (B-CLL) is the most common adult leukaemia in the western world, and is characterized by the clonal expansion of CD5+CD23+ B cells. There is abundant evidence for impaired immune function in CLL patients, with infection remaining an important cause of morbidity and mortality and an increased incidence of autoimmune diseases [1,2]. A number of well-characterized T cell defects are found in CLL patients, including up-regulation of CD152 [cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4][3] and reduced expression of CD28 [4], CD80, CD86 and CD154 [5] in comparison to healthy controls. Functionally, T cells from CLL patients exhibit skewing towards a T helper type 2 (Th2) profile [6,7] and show impaired cytotoxic killing of autologous tumour [8]. CLL cells also express high levels of immunomodulatory factors, including transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interleukin (IL)-10 [9,10]. Gene expression profiling of T cells from CLL patients and co-culture experiments of healthy T cells with CLL cells demonstrates defects in cytoskeleton formation, vesicle trafficking and cytotoxicity that appear contact-mediated [11].

CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are naturally occurring T cells which originate from the thymus [12] or following conversion to Tregs in the periphery [13–16], and play a central role in the maintenance of peripheral tolerance by suppression of autoreactive lymphocytes [17,18]. In murine models Tregs prevent autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [19,20] and inhibit anti-tumour immune responses [21–23].

Regulatory T cells are enriched within the CD4+CD25hi population and inhibit proliferation and cytokine release by conventional CD4+CD25- T cells [24]. Unfortunately, CD25 is not an ideal marker for human Tregs as recently activated effector cells up-regulate CD25. The forkhead transcription factor FoxP3 has been shown to be a more reliable Treg marker and is crucial for the development and function of Tregs[25–27]. Although expressed at high levels by Tregs, FoxP3 can be induced in CD4+CD25- T cells activated with corticosteroids, oestrogen and TGF-β[14–16]. Reduced expression of CD127 (IL-7Rα) on CD4+CD25+ T cells has also been recognized as being a characteristic of Tregs and is used phenotypically to identify Tregs to study suppressor function [28,29].

A decrease in Treg number or function is observed typically in patients with autoimmune disease [30,31], whereas increased numbers are often observed in those with cancer [32–34]. During the past few years the importance of Tregs has been studied in patients with haematological malignancies, but the conclusions remain somewhat uncertain. Increased frequencies of Treg cells have been observed in CLL, multiple myeloma, B non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) [35], whereas reduced numbers have also been reported in Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma [36,37]. Such discrepancies might be related partly to phenotypic definition of Treg and clinical variation within cohorts.

In this study we have examined the expression of proteins associated with Tregs on the T cell repertoire in patients with CLL at different stages of disease. The data reveal an altered pattern of expression on all T cell subsets which leads ultimately to the expansion of functional Tregs.

Materials and methods

Patients

Forty-three CLL patients (median age: 74 years) and 16 age-matched controls (median age: 76 years) were recruited following informed consent (approved by the South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee) from the University Hospitals Birmingham Foundation Trust and Heart of England National Health Service (NHS) Trust. CLL disease was classified according to Binet stage: seven were stage A, eight were stage B and 20 were stage C. Within the stage C group, three were on chlorombacil (CLB), two were on combined cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin and prednisolone (CHOP) and 11 were or had been on (the last 10 months) fludarabine. Patient stage, CD38 status (as determined by flow cytometry by clinical immunology laboratory) and ages are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characterisitics

| CD38 status (n) | Median age in years (range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | Pos. | Neg. | n.d. | ||

| Healthy controls | 16 | 76 (65–92) | |||

| CLL (all Binet stages no Rx) | 24 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 74 (38–92) |

| Stage A | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 74 (38–92) |

| Stage B | 8 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 61 (51–84) |

| Stage C | 9 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 74 (50–87) |

| Stage C + flu | 7 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 63 (56–86) |

| Stage C + post-flu | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 74 (50–87) |

| Stage C + CLB | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 81 (74–87) |

| Stage C + CHOP | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 48 (35–61) |

Rx: treatment; Flu: fludarabine; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisolone; CLB: chlorambacil; Pos.: positive; neg.: negative; n.d.: not done; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) isolation

Peripheral blood was taken into sodium heparin tubes and PBMC isolated by density centrifugation over lymphoprep (Robbins Scientific, Solihull, UK). PBMC were used fresh or frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen until further use.

Antibodies

The following conjugated antibodies were used: CD4 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD4 PE-Texas Red (ECD), CD45RO PE-Texas Red (ECD), CD25 PC5, CD80 phycoerythrin (PE), CD86 PE (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, UK), FoxP3 PE (clone PCH101), CD127 FITC, CD4 PC7, CD3 pacific blue, CD19 pacific blue, CD27 AF750 (ebioscience/Insight Ltd, Hatfield, UK), CD70 FITC and CD4 PE-cyanin 7 (Cy7) (Becton Dickinson, Oxford, UK).

Flow cytometry

PBMC were surface stained for 20 min, washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/0·5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, Dorset, UK) and run on a flow cytometer (EPICS-XL; Beckman Coulter, Dunstable, UK or Cyan; Dako, Ely, UK). For FoxP3 staining, after surface labelling, cells were fixed and permeabilized and stained for FoxP3 following the manufacturer's instructions (ebioscience/Insight Ltd) prior to acquistion by flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using WinMDI (Joseph Trotter, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) and Summit version 4·3 (Dako).

Isolation of CD4+CD25high and CD4+CD25- T cells

PBMC from CLL patients and healthy controls were enriched for T cells using anti-CD3 PE-microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec Ltd, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The non-CD3 fraction from controls was irradiatied (40 Gy) and used as feeders. CD3-enriched cells were subsequently stained with antibodies to CD4 and CD25 and sorted [BD fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS)Calibur; BD Biosciences] on CD4+ CD25high T regulatory T cells and CD4+CD25- effector T cells.

Suppressor assays

RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (1000 IU/ml)/streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and 10% human serum (HD Supplies, Buckingham, UK) was used in all assays. Direct ‘add-back’ experiments were performed as described previously [38]. Briefly, 1 × 104 CD4+CD25- cells were incubated in the presence of phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, Sigma, Dorset, UK) at (5 µg/ml) and 1 × 104 irradiated (40 Gy) autologous or allogeneic CD3-depleted PBMC either alone or with CD4+CD25high at a ratio of 1:1. All incubations were run at least in duplicate in 96-well plates in a final volume of 200 µl. At 72 h, 1 µCi [3H]-thymidine was added to each well and proliferation by [3H]-thymidine incorporation was assessed after a further 16 h.

CLL co-culture experiments

CLL tumour cells were either used directly or preactivated by culture with irradiated CD40L-transfected L cells (100Gy), IL-4 (1000 U/ml) (Peprotech, London, UK) and TNF-α (100 U/ml) (Sigma) for 6 days. Allogeneic non-Tregs (CD4+CD127+CD25-) were sorted (Mo-Flow; Beckman Coulter) and incubated with (1) different doses of CLL (10:1–1:4); (2) allogeneic activated B cells (B cell blasts: CD19+ B cells from healthy donors preactivated in same procedure as described for CLL); (3) CD3/28 beads (Dynal; Invitrogen) for 4–5 days and FoxP3 induction assessed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Depending on comparisons for two or for more than two groups, and whether unpaired or paired data, the following non-parametric tests were used: Mann–Whitney U-test; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; Kruskal–Wallis or the Friedman test followed by the Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. A P-value of <0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells is increased in patients with untreated CLL due to increased expression of FoxP3 within the CD4+CD25- T cell subset

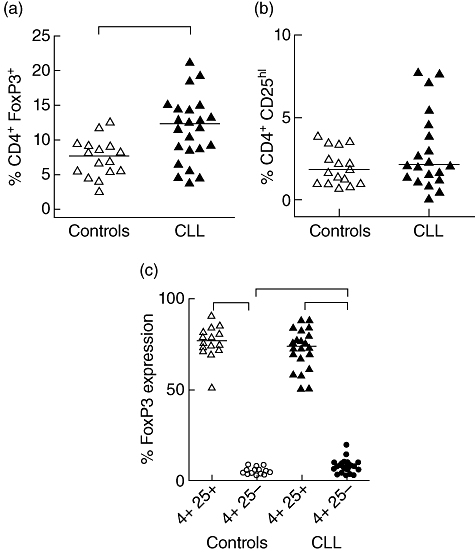

Our initial analysis determined the frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells in untreated patients and controls and demonstrated a marked increase within the patient cohort, where FoxP3+ was expressed in 12% of the CD4+ T cell repertoire compared to 8% of controls (Fig. 1a, P < 0·01). In order to correlate these findings with CD25 expression, which has previously been utilized as a phenotype for Tregs in CLL, we then determined the frequency of CD4+CD25high T cells in each group. In contrast to previous reports, we failed to observe an increase in the number of CD4+CD25high cells in patients with CLL (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Frequency and expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) in CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients and age-matched controls. Frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ (a) and CD4+CD25hi (b) T cells in untreated CLL patients and age-matched controls. Expression of FoxP3 (c) in CD4+CD25+ (triangles) and CD4+CD25- (circles) T cells from CLL patients (closed symbols) and controls (open symbols). Solid line represents median. *P < 0·05 using Mann–Whitney U-test.

In order to explain this discrepancy we next examined expression of FoxP3 in both CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- populations (Fig. 1c), as it has been reported that FoxP3 expression can be observed in CD25- T cell subsets [14,39–41]. As expected, expression of FoxP3+ was much higher in the CD25high subset compared to CD25- cells, with an increase of 17-fold and 10·5-fold, respectively, in both the control and CLL patients (P < 0·001). However, the frequency of the CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ subset, which is usually taken to represent a ‘classic’ regulatory phenotype, was not increased in patients with CLL (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, FoxP3 expression was increased within the CD4+CD25- subset where it was observed in 7% of cells within the patient group, an increase of nearly twofold over controls (4·5%; P < 0·05) (Fig. 1c). This reveals that the increased frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells in patients with CLL is due to a selective increase in the CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ population.

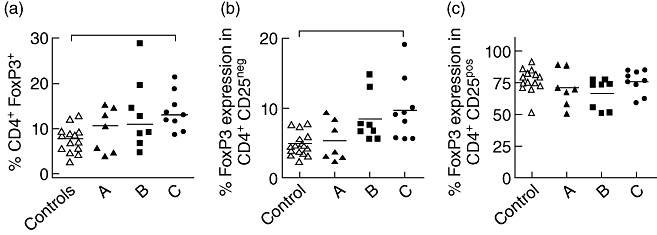

The increase in Tregs associated with CLL is seen selectively in patients with untreated advanced disease

As we had observed that the percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells was increased in patients with untreated CLL, we then went on to see how this correlated with the stage of the disease. The Binet classification assigns patients with CLL to one of three groups, A–C, based on extent of disease. Interestingly, when we studied the proportion of CD4+FoxP3+T regulatory cells in patients at different stages of disease, only those with untreated stage C disease had increased values compared to the control group, with a median of 13% of the CD4+ T cell pool compared to 7·7% in controls (P < 0·05) (Fig. 2a). Importantly, this increase was again due entirely to an increased proportion of CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ T cells, with no increase being observed in the ‘classical’ regulatory CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ subset (Fig. 2b,c; P < 0·05). Differences in the frequencies of CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ T cells mirrored differences in the absolute numbers of CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ T cells in the three CLL stages (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

T regulatory cell frequency in different C chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) disease states. Comparison of CD4+ forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+ T cell frequency in healthy controls and untreated CLL patients (Binet stages A, B and C) (a). Expression of FoxP3 in CD4+CD25- (b) and CD4+CD25+ (c) T cells from CLL patients at different stages of disease (a–c; according to Binet staging). Solid line represents median. P < 0·05 using Kruskal–Wallis test as indicated by bars on top of graph.

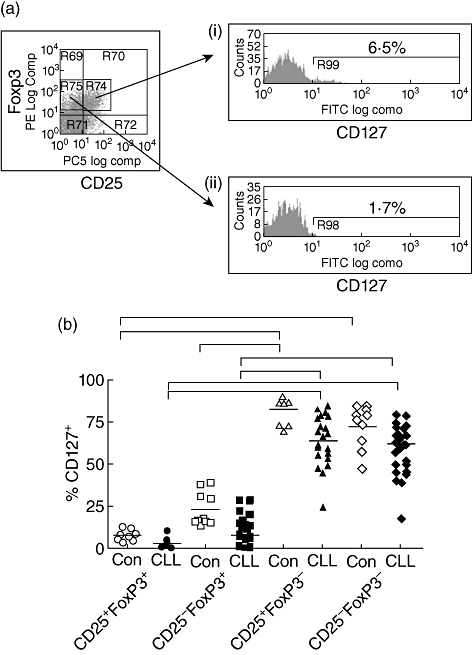

CD127 expression is reduced on T cells in all subsets from CLL patients

In order to further study the observation that FoxP3 expression was increased on CD4+CD25- T cells in patients with CLL, we then examined additional phenotypic markers of this subset. CD127 is the IL-7 receptor, and loss of CD127 expression is a valuable phenotypic marker for the regulatory T cell subset. As expected, CD127 expression was low on FoxP3+ T cells, but it was of interest to observe that this was true in both the CD25+ and CD25- subsets [Fig. 3a(i) and (ii), respectively]. We therefore examined the expression of CD127 on CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ and CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ T cells in the patient and control groups. Expression was reduced most markedly in CLL subjects in whom only 2·8% and 8%, respectively, of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ and CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ T cells expressed CD127 compared to 7·5% and 16·9% of control subjects (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Expression of CD127 on different forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)-expressing T cell populations. A representative flow cytometric plot demonstrating FoxP3 versus CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells. (a): histogram plots of CD127 expression on gated regions from (a) (i) CD25+FoxP3- and (ii) CD25- FoxP3+ T cells. Percentage above bar represents % of gated cells positive for CD127. Percentage of CD127-positive cells (y-axis) in different CD25+/− and FoxP3+/− T cell populations are shown for controls and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients (Fig. 3b). Solid line represents median. P < 0·05 using Friedman's test (paired non-parametric); significant differences are indicated by bars on top of graph.

In addition, although CD127 expression was much higher on FoxP3- T cells in both the CD25+ and CD25- subsets, there was a marked down-regulation of expression on these populations in the CLL patient group. In particular, CD127 expression was observed on only 67% of the CD25+FoxP3- population in patients compared to 86% in controls, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3b). The trend for lower levels of CD127 on all CD4+ T cell populations in patients with CLL, irrespective of FoxP3 or CD25 expression, reveals a generalized loss of CD127 expression on T cells in patients with CLL.

Expression of CD27 is increased on T cells in patients with CLL

CD27 is the receptor for CD70 and is expressed on a wide range of B and T cell subsets, where it supports cell survival and proliferation. CD27 is highly expressed on T regulatory cells and was indeed observed on the great majority of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells from both CLL patients (median 95%) and control subjects (median 85·1%). However, in keeping with our previous observations regarding FoxP3 and CD127, we also saw a difference in the expression pattern of CD27 on all CD4+ T cell subsets in patients with CLL. Expression of CD27 was particularly high on the CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ subset where it measured 90% in patients compared to only 50% in control subjects (P < 0·01) (Fig. 4a). In the CD25-FoxP3- subset it was also increased at 70·6% versus 58·4% in controls.

Fig. 4.

CD27 expression on CD4+ T cells. (a) Comparison of CD27 expression on different CD4+ T cell populations between chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and controls. Bar indicates median value. *P < 0·05 using Friedman's test (paired non-parametric) and Kruskal–Wallis test (CLL versus control); significant differences are indicated by bars on top of graph. Correlation between (B) CD27 and FoxP3 on CD4+CD25neg T cells populations. Line represents linear regression fit and r-value and P-value determined by Spearman's rank correlation test.

In order to assess whether there was a relationship between the increase in expression of CD27 and FoxP3 that we had observed independently in the CD4+CD25- subset, we looked for a correlation between these two values (Fig. 4b). We found that there was a significant positive correlation.

T cells cultured in the presence of CLL tumour cells acquire a marked increase in FoxP3 expression

Our finding of increased expression of FoxP3 in CD4+CD25- T cells from patients with CLL patients led us to consider if the presence of tumour cells was inducing a regulatory phenotype in the CD25- T cell compartment. CD4+CD25-CD127+ T cells were therefore sorted from healthy donors, as this population contains extremely low levels of FoxP3+ T cells (Fig. 5a and data not shown). CLL tumour cells were isolated either directly ex vivo or were activated for 6 days on CD40L-transfected L cells in the presence of IL-4 and TNF-α. Preactivation led to increased expression of CD80, CD86 and CD70 on CLL tumour cells (Supplementary Fig. S2). CD4+CD25-CD127+ T cells were then incubated either alone, in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 beads or in co-culture at a 1:10 ratio with primary CLL cells (n = 12), preactivated CLL cells (n = 12) or allogeneic activated B cells (n = 5). The relative induction of FoxP3 was assessed after 5 days by flow cytometry. Incubation with fresh CLL tumours cells led to a sixfold increased induction of FoxP3 in the T cell subset in comparison to T cells cultured in the presence of allogeneic B cells (8·4 versus 1·4). The activation status of the CLL tumour appeared to have no influence on this response. Importantly, no significant increase in FoxP3 expression was observed after co-culture with B cell blasts (Fig. 5b,c).

Fig. 5.

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) tumour cells enhance expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) in CD4+CD25- T cells (a) Purified CD4+CD25-CD127+ T cells were sorted by flow cytometry and shown to be negative for FoxP3 expression. (b) Cells were then cultured alone or with the addition of either B blasts, directly isolated CLL cells or preactivated CLL cells. Incubations were performed at a 1:10 ratio for 5 days. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown for each culture condition. The percentage in the top right quadrant indicates the number of CD4+ T cells which stain positively for FoxP3. (c) Summary of relative FoxP3 induction in CD4+CD25- T cells following co-culture with B blasts (n = 5), directly isolated ex vivo CLL (n = 12) or preactivated CLL (n = 12). T cells alone were used as baseline for calculating FoxP3 induction (y-axis). Column bars indicate mean ± standard error (s.e.). P < 0·05 using Kruskal–Wallis test as indicated by bars on top of graph.

The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells is initially increased during fludarabine chemotherapy before falling to levels comparable to controls

As patients with the advanced disease have the most marked alterations in T cell profile, it was considered important to assess the significance of chemotherapy on the changes observed. Fludarabine is one of the most commonly used agents in the management of CLL and has been reported to show some selectivity in the induction of apoptosis of T regulatory cells in vitro[35]. We performed a cross-sectional and prospective analysis of CD4+FoxP3+ cell number and percentage in patients undergoing fludarabine chemotherapy in order to determine the kinetics of T cell response to therapy. Interestingly, there was an initial increase in the percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells in the early period following the start of chemotherapy to a median level of 20·4% of the CD4 subset (Fig. 6a, P < 0·01; Fig. 6b). Continuing treatment was followed by a reduction in the number of both the total CD4+ and CD4+FoxP3+ subset, but the percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ cells was ultimately reduced to a median of 5·8% which was comparable to healthy donors. Despite these differences in the kinetics of response, the overall half-life of decline was identical for both the total CD4+ and CD4+FoxP3+ subsets at 56 days (Fig. 6c). There was no statistical difference in the CLL Treg frequencies between the fludarabine-treated CLL patients and the untreated stage C CLL patients.

Fig. 6.

Effect of chemotherapy on regulatory T cell frequency. Effect of different drug treatments (x-axis) on CD4+ forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+ frequency in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients (a). Solid line represents median. P < 0·05 using Friedman's test (paired non-parametric) as indicated by bars on top of graph. CD4+FoxP3+ T cells were enumerated prior to, during and post-fludarabine treatment (x-axis in weeks) in two patients (b). Number of total CD4+ (solid triangle) and CD4+FoxP3+ T cells (open triangles) per µl of blood (primary y-axis) and % CD4+FoxP3+ T cells (closed circles) (secondary y-axis). (c) Half-life in decay of total number of CD4+ (squares) and CD4+FoxP3+ (triangles) T cells following fludarabine treatment (≥ 30 weeks from start of treatment).

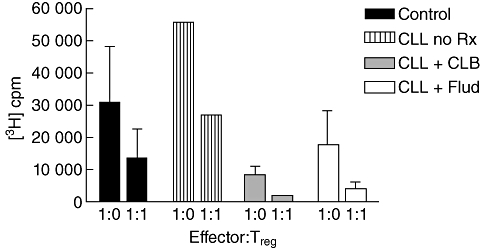

The function of Tregs is retained in patients with CLL and is not influenced by chemotherapy

To confirm that the phenotypic changes observed in the patient group did indeed correlate with functional capacity for T cell suppression, cells from CLL patients were assessed for activity in a [3H]-thymidine suppressor assay. Regulatory cells were used in ‘add back’ assays to suppress allogeneic T cell cultures and thymidine was used as a measure of cell proliferation. Regulatory cells were sorted from patients who were untreated or those undergoing treatment with chlorambucil or fludarabine. When compared to the control group, no differences were observed in the capacity of the cells to suppress T cell proliferation, indicating that there are no functional differences in Tregs from different stages of disease (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Regulatory T cells are functional in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients and are not influenced by chemotherapy. Assays of functional suppressor activity were performed with CD4+CD25high T cells isolated from CLL patients who were currently not on treatment (n = 1; lined bars); patients during treatment with either chlorambucil (CLB) (n = 2; grey bars) or fludarabine (n = 3; open bars). Values were compared to those seen in healthy age-matched controls (n = 3; black bars). CD4+25- effector T cells were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) for 72 h, with or without patient CD4+CD25hi T cell at an effector : target ratio 1:1 or 1:0, in the presence of irradiated antigen-presenting cells (APC) and then pulsed with [3H]-thymidine for 16 h. The mean incorporation (± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.)] of [3H]-thymidine (cpm) (y-axis) is represented as bars for each group cohort.

Discussion

Several studies have established that the number of Tregs is increased in patients with solid tumours [32–34]. For haematological malignancies the story is less clear, with conflicting data in relation to both the number and function of these cells [37,42]. Some discrepancies may be explained by the use of different markers to define Tregs and also by variation in the patient and control populations studied. In chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, Beyer et al. (2005) defined Tregs using the phenotype of CD4+CD25hi and showed an increase that was correlated with disease stage and associated with impairment of Treg function during chemotherapy. Giannopoulos et al. (2008) also showed an increase in the frequency of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in 80 CLL patients compared to healthy volunteers, with a positive association with disease progression and an inverse correlation with functional T cell responses against viral and tumour antigens [43]. Most recently D'Arena et al. (2011) defined Tregs by the phenotype CD4+CD25hiCD127low and again showed increased absolute numbers of Tregs in CLL patients compared to controls and a correlation with more advanced clinical stage [44].

In our study we utilized FoxP3 as the definitive Treg marker and observed an increased frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells in patients with CLL. However, this increase was confined to the CD4+CD25-FoxP3+ compartment and was seen only in advanced disease. Some of the differences seen in our study compared to previous work could relate to the age of the control populations studied. Treg cells increase with age [45], and in our study the mean age of controls and patients was 76 and 74 years, respectively, whereas other studies have comparable values of 46 and 64 years [35].

Perhaps the most interesting observation of our study was that the phenotype of the total CD4+ T cell subset was altered in patients with CLL, irrespective of CD25 or FoxP3 expression. The pattern showed a shift towards the regulatory cell profile with a generalized increase in expression of CD27 and a trend for a reduction in levels of CD127 (Fig. 8). Linqvist et al. [46] looked at expression of cytolytic markers and tumour cell killing by CD4+ T cells in CLL patients and demonstrated that CD4+ T cells were capable of cell killing and increased expression of the cytolytic marker CD107a globally on all CD4+ T cell subgroups in CLL compared with healthy donors.

Fig. 8.

Schematic representation of the profile of CD27 and CD127 expression on CD4+ T cells during differentiation into regulatory [forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+] or effector (FoxP3-) T cells. Patients with CLL exhibit an accelerated pattern of CD27 expression and loss of CD127. Expression of CD27 (blue) and CD127 (red) on T cells through their differentiation in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) (dashed line) and control (solid line) patients.

It is not clear if CD27 and CD127 are involved primarily in the mechanisms that drive this differentiation to a regulatory phenotype. CD127 is the high-affinity IL-7 receptor α-chain and FoxP3 has been reported to regulate negatively the expression of CD127 by binding to the CD127 gene promoter [29]. The trend for a reduction of CD127 on T cells in patients with CLL raises the question as to how this effect may be mediated. IL-7 levels are increased in several inflammatory disorders and mRNA expression has been observed in CLL tumour cells [47,48], raising the possibility that local paracrine production leads to down-regulation of CD127 on T cells within the tumour microenvironment. CD27 expression has been correlated with increased levels of functional suppression [49] and the ligand for CD27 is CD70, which is expressed on a range of cells, including B cell tumours. The interaction of CD70 with CD27 has been demonstrated as a potential mechanism for the induction of FoxP3 expression and CD70 was indeed highly expressed on B cells in our patient group. This may therefore reflect a primary mechanism behind the observed shift in subset distribution, although we did not find any correlation between CD70 expression by tumour cells and the percentage of CD25-FoxP3+ cells (data not shown). In addition to CD27–CD70 interactions [50], an increase in TGF-β in the patient group may play a role, as this can induce FoxP3 in CD4+CD25- T cells [14]. An important aim now will be to investigate the potential mechanisms through which this effect could be mediated and how co-culture with CLL tumour cells promotes FoxP3 expression. The up-regulation of CD70, CD80 and CD86 expression that was observed following preactivation of CLL cells (Supplementary Fig. S2) did not augment FoxP3 induction, suggesting that other co-stimulatory pathways are critical (Fig. 5c).

Our finding of an expansion in the CD4+CD25-FoxP3 compartment has also been reported in NHL [13]. Initial reports described this expansion as occurring only in the lymph node compartment, although a later report revealed that changes could also be observed at the systemic level and were correlated with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) measurement, a surrogate marker of tumour burden [51]. Our observations show that the influences of tumour cells on the T cell repertoire are particularly marked in patients with a systemic disease such as leukaemia.

We were interested in the response of T cell subsets to chemotherapy and observed that Tregs were reduced to a low level following cessation of fludarabine therapy. Interestingly, there was an initial, transient rise in the proportion of CD4+FoxP3+ T cells during the early period of therapy, which in some patients reached a value of nearly 50%. This observation may reflect a relative resistance of this subset to chemotherapy in vivo, or could potentially be related to a shift of lymphocyte subsets between tissue compartments. It is interesting to consider these observations in relation to the clinical features of patients with CLL. The reduction in the frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ cells after chemotherapy might be expected to reduce the overall level of immune suppression in the patient. However, susceptibility to infection is actually increased following fludarabine therapy and presumably reflects the overall suppression of the T cell pool. Nevertheless, patients often achieve prolonged periods of disease control, and it is tempting to suggest that the reduction in CD4+FoxP3+ T cells allows the establishment of a host response to tumour proliferation.

The observation that the global CD4+ T cell repertoire is driven towards a regulatory phenotype in patients with CLL is likely to be of considerable relevance to the clinical feature of the disease. An increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved should offer the potential for novel therapeutic interventions.

Disclosure

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Fig. S1. Frequency of CD4+CD25+forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients and age-matched controls. Percentage of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells from CLL patients (closed symbols) and controls (open symbols). Solid line represents median.

Fig. S2. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules on chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and preactivated CLL cells. A representative example of flow cytometric histogram plots showing CD70, CD80 and CD86 expression on matched CLL (dashed line) and preactivated CLL (solid line) samples. Bar depicts % positive expression on preactivated CLL cells.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Caligaris-Cappio F, Hamblin TJ. B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a bird of a different feather. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:399–408. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foon KA, Rai KR, Gale RP. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: new insights into biology and therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:525–39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-7-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motta M, Rassenti L, Shelvin BJ, et al. Increased expression of CD152 (CTLA-4) by normal T lymphocytes in untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1788–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scrivener S, Kaminski ER, Demaine A, Prentice AG. Analysis of the expression of critical activation/interaction markers on peripheral blood T cells in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: evidence of immune dysregulation. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:959–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantwell M, Hua T, Pappas J, Kipps TJ. Acquired CD40-ligand deficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med. 1997;3:984–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Totero D, Reato G, Mauro F, et al. IL4 production and increased CD30 expression by a unique CD8+ T-cell subset in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:589–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay NE, Han L, Bone N, Williams G. Interleukin 4 content in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) B cells and blood CD8+ T cells from B-CLL patients: impact on clonal B-cell apoptosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:760–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krackhardt AM, Harig S, Witzens M, Broderick R, Barrett P, Gribben JG. T-cell responses against chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: implications for immunotherapy. Blood. 2002;100:167–73. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotz M, Ranheim E, Kipps TJ. Transforming growth factor beta as endogenous growth inhibitor of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J Exp Med. 1994;179:999–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayad L, Keating MJ, Reuben JM, et al. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 levels in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: correlation with phenotypic characteristics and outcome. Blood. 2001;97:256–63. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorgun G, Holderried TA, Zahrieh D, Neuberg D, Gribben JG. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells induce changes in gene expression of CD4 and CD8 T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1797–805. doi: 10.1172/JCI24176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pillai V, Karandikar NJ. Human regulatory T cells: a unique, stable thymic subset or a reversible peripheral state of differentiation? Immunol Lett. 2007;114:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang ZZ, Novak AJ, Ziesmer SC, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. CD70+ non-Hodgkin lymphoma B cells induce Foxp3 expression and regulatory function in intratumoral CD4+CD25 T cells. Blood. 2007;110:2537–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, et al. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25– T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng SG, Wang JH, Stohl W, Kim KS, Gray JD, Horwitz DA. TGF-beta requires CTLA-4 early after T cell activation to induce FoxP3 and generate adaptive CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3321–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehervari Z, Sakaguchi S. Development and function of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Naturally-occurring CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: central players in the arena of peripheral tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suri-Payer E, Amar AZ, Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1212–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory t cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163:5211–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casares N, Arribillaga L, Sarobe P, et al. CD4+/CD25+ regulatory cells inhibit activation of tumor-primed CD4+ T cells with IFN-gamma-dependent antiangiogenic activity, as well as long-lasting tumor immunity elicited by peptide vaccination. J Immunol. 2003;171:5931–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turk MJ, Guevara-Patino JA, Rizzuto GA, Engelhorn ME, Sakaguchi S, Houghton AN. Concomitant tumor immunity to a poorly immunogenic melanoma is prevented by regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200:771–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;167:1245–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–42. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1693–700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shevach EM. Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:971–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray CP, Arosio P, Hersey P. Association of increased levels of heavy-chain ferritin with increased CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell levels in patients with melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2551–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo EY, Chu CS, Goletz TJ, et al. Regulatory CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells in tumors from patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and late-stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4766–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beyer M, Kochanek M, Darabi K, et al. Reduced frequencies and suppressive function of CD4+CD25hi regulatory T cells in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after therapy with fludarabine. Blood. 2005;106:2018–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvado MT, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin's lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1467–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prabhala RH, Neri P, Bae JE, et al. Dysfunctional T regulatory cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:301–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng WF, Duggan PJ, Ponchel F, et al. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) cells: a naturally occurring population of regulatory T cells. Blood. 2001;98:2736–44. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan ME, van Bilsen JH, Bakker AM, et al. Expression of FOXP3 mRNA is not confined to CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells in humans. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allan SE, Passerini L, Bacchetta R, et al. The role of 2 FOXP3 isoforms in the generation of human CD4+ Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3276–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI24685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:129–38. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyer M, Schultze JL. Regulatory T cells in cancer. Blood. 2006;108:804–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giannopoulos K, Schmitt M, Wlasiuk P, et al. The high frequency of T regulatory cells in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia is diminished through treatment with thalidomide. Leukemia. 2008;22:222–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D'Arena G, Laurenti L, Minervini MM, et al. Regulatory T-cell number is increased in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients and correlates with progressive disease. Leuk Res. 2011;3:363–8. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gregg R, Smith CM, Clark FJ, et al. The number of human peripheral blood CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells increases with age. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:540–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindqvist CA, Christiansson LH, Thörn I, et al. Both CD4(+) FoxP3(+) and CD4(+) FoxP3(-) T cells from patients with B-cell malignancy express cytolytic markers and kill autologous leukaemic B cells in vitro. Immunology. 2011;133:296–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frishman J, Long B, Knospe W, Gregory S, Plate J. Genes for interleukin 7 are transcribed in leukemic cell subsets of individuals with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Exp Med. 1993;177:955–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long BW, Witte PL, Abraham GN, Gregory SA, Plate JM. Apoptosis and interleukin 7 gene expression in chronic B-lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1416–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koenen HJ, Fasse E, Joosten I. CD27/CFSE-based ex vivo selection of highly suppressive alloantigen-specific human regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:7573–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ranheim EA, Cantwell MJ, Kipps TJ. Expression of CD27 and its ligand, CD70, on chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 1995;85:3556–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mittal S, Marshall NA, Duncan L, Culligan DJ, Barker RN, Vickers MA. Local and systemic induction of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell population by non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2008;111:5359–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.