Abstract

Polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR), or microsatellite, loci have been widely used to analyze chimerism status following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). The presence of a patient’s DNA, as identified by STR analysis, may indicate residual or recurrent malignant disease or may represent normal hematopoiesis of patient origin. The ratio of patient-derived to donor-derived alleles is used to calculate the relative amount of patient cells (both benign and malignant) to donor cells. STRs on chromosomes known to be gained or lost in a patient’s tumor are generally ignored because it is difficult to perform meaningful calculations of mixed chimerism. However, in this report, we present evidence that STR loci on gained or lost chromosomes are useful in distinguishing the benign or malignant nature of chimeric DNA. In the peripheral blood or bone marrow of four HSCT patients with leukemia or lymphoma, we identified tumor DNA on the basis of STR loci showing copy number alteration. We propose that a targeted evaluation of STR loci showing altered copy number in post-transplant chimerism analysis can provide evidence of residual cancer cells.

Keywords: short tandem repeat, microsatellite, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, chimerism, leukemia relapse

Introduction

Short tandem repeat (STR), or microsatellite, loci have been widely used for analysis of engraftment and chimerism status in patients following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).1,2 Mixed chimerism indicates the presence of recipient as well as donor cells in the post-transplant recipient peripheral blood or bone marrow.3,4 Since DNA of patient origin may be derived from cancer cells or from reconstitution by normal hematopoietic elements, the presence of DNA of patient origin does not reliably predict the relapse of leukemia.5–10 Immunohistochemical study, flow cytometric analysis, cytogenetic study, fluorescent in situ hybridization and a variety of molecular diagnostic assays may be used to confirm the presence of residual cancer cells.

In diagnostic laboratories, multiple loci are recommended for calculation of the percentage of mixed chimerism.11,12 Those loci showing gain or loss of an allele in the original leukemic sample are generally avoided. Chromosomal gain or loss obviously affects STR analysis and may lead to errors in the calculation. In contrast to the standard approach, we demonstrate in this report that both informative and non-informative loci with gain or loss of alleles can be used as a marker of impending relapse.

Materials and Methods

DNA was isolated from peripheral blood or bone marrow specimens using a Qiagen EZ1 automated nucleic acid extractor and reagents (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described previously.13 In some cases, T lymphocytes were purified from peripheral blood using a RoboSepR machine (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) with anti-CD3 antibody according to the manufacture’s instructions. PCR was performed using the AmpFlSTR Profiler kit or AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction described previously.13 Nine microsatellite loci (D3S1358 at chromosome 3p, vWA at 12p12-pter, FGA at 4q28, THO1 at 11p15.5, TPOX at 2p25.3, CSF1PO at 5q33.3-34, D5S818 at 5q21-31, D13S317 at 13q22-31 and D7S820 at 7q) as well as the amelogenin locus at X (p22.1-22.3) and Y (p11.2) chromosomes were analyzed using the AmpFlSTR Profiler kit (Table 1). An additional 6 loci were included in the AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit: D2S1338 at 2q35-37.1, D8S1179 at chromosome 8, D16S539 at 16q24-qter, D18S51 at 18q21.3, D19S433 at 19q12-13.1 and D21S11 at 21q11.2 (Table 1). One μl PCR products and 9 μl deionized formamide/GeneScan-500 [ROX] for Profiler and deionized formamide/GeneScan-500 [LIZ] for Identifiler (Applied Biosystems) were mixed according to the manufacture’s protocol, heated at 95°C for 2 minutes and placed on ice for at least 1 minute before electrokinetic injection on the ABI 3100 or 3130 capillary electrophoresis instrument (Applied Biosystems) as described previously.14 Patient and donor samples were analyzed before transplant. At our institution, post-transplant chimerism is routinely calculated using an average of at least 2 informative loci.13 Our standard chimerism calculation is: (peak height of recipient-specific allele)/(sum of peak heights of recipient-specific and donor-specific alleles) X 100%. The Johns Hopkins Medicine institutional review board granted approval to this study.

Table 1.

Chromosomal abnormalities of AML/MDS, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in accelerated phase, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma involving microsatellite loci included in the AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit.

| Hematological malignancy | Chromosomal abnormalities | Identifiler loci | Gain or loss of allele |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPOX (2p25.3) | |||

| D2S1338 (2q35-37.1) | |||

| AML/MDS | del(3p) | D3S1358 (3p21) | Loss |

| FGA (4q28) | |||

| AML/MDS | del(5q), −5 | CSF1PO (5q33.3-34) | Loss |

| AML/MDS | del(5q), −5 | D5S818 (5q21-31) | Loss |

| AML/MDS | del(7q), −7 | D7S820 (7q21.11) | Loss |

| hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma | i(7q) | D7S820 (7q21.11) | Gain |

| AML/MDS, CML | +8 | D8S1179 (8q24.13) | Gain |

| THO1 (11p15.5) | |||

| CLL | +12 | vWA (12p12-pter) | Gain |

| AML/MDS | del(12p) | vWA (12p12-pter) | Loss |

| AML/MDS, CLL | del(13q) | D13S317 (13q22-31) | Loss |

| D16S539 (16q24-qter) | |||

| AML/MDS | −18 | D18S51 (18q21.3) | Loss |

| CML | +19 | D19S433 (19q12-13.1) | Gain |

| AML/MDS | −21 | D21S11 (21q11.2) | Loss |

| AML/MDS | −Y | amelogenin (Xp22.1-22.3, Yp11.2) | Loss |

Results

Case 1

A 3 year-old male patient with refractory acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) with monosomy 7 received an HLA-haploidentical non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from his mother. The pre-transplant analysis of the peripheral blood from the patient (which contained some leukemic cells) and the donor showed multiple informative microsatellite loci using Identifiler, including D16S539 (Fig. 1A and 1B) and D7S820 (263 and 279 bases for the patient and 279 and 283 bases for the donor, Fig. 1E and 1F). The imbalance of the two D7S820 loci in the patient (263 base allele: 1089 relative fluorescent units (RFU) and 279 base allele: 2062 RFU, ratio of 279/263 = 1.89) was consistent with persistent leukemia cells with monosomy 7 (loss of the 263 base allele).

Fig. 1.

Identifiler microsatellite analysis at loci D16S539 (A–D) and D7S820 (E–H) from case 1; pre-transplant samples of patient (A and E) and donor (B and F) and post-transplant samples at 1 month: unsorted bone marrow (C and G) and sorted CD3+ T cells (D and H). Arrows indicate the presence of a recipient-specific 268-base D16S539 allele in the post-transplant samples (C, D, H). The presence of the recipient-specific 268 base D16S539 allele and absence of a recipient-specific 263 base D7S820 allele (▼, G) in the bone marrow and the presence of the recipient-specific 263 base D7S820 allele in T cells (H) is consistent with residual leukemia with monosomy 7 among the bone marrow white cell population.

At one month after transplantation, a bone marrow aspiration showed a normal number of blasts (4%) and no phenotypically abnormal blasts were detected by flow cytometric analysis. Chimerism analysis of the bone marrow revealed an average of 8% patient DNA (D21S11: 7.5%, D16S539: 8.3% and D19S433: 8.2%) (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Based on the calculation r263/(r263+d283) = 8% at locus D7S820 (r263: peak height of recipient-specific allele at 263 bases; d283: peak height of donor-specific allele at 283 bases, 3798 RFU), a peak height of approximately 330 RFU is anticipated at 263 bases if the entire recipient DNA was derived from normal hematopoietic cells. No 263 base peak was detected (Fig. 1G), even after longer capillary electrophoresis injection (data not shown). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis showed 5.2% cells with loss of one copy of 7q, consistent with the lack of the 263 base peak. In contrast, chimerism analysis of CD3+ T cells isolated from the bone marrow showed 44% recipient DNA based on locus D7S820, r263/(r263+d283) = 336/(336+423) (Fig. 2H). This was consistent with the chimerism status calculated from the other loci, an average of 46% patient DNA (Fig. 1D), indicating that the T cell population contained few or no leukemic blasts. Thus, the STR analysis suggested residual acute leukemia after transplantation, despite the normal morphologic and immunophenotypic findings. At 2 months post-transplant, no donor DNA was detected in the CD3+ T cells isolated from the peripheral blood and the unsorted peripheral blood. The peak heights of 279 base allele and 263 base allele of D7S820 loci were 1713 and 2309 (ratio: 74%) for CD3+ T cell, and were 1489 and undetectable for unsorted peripheral blood samples (data not shown). These results further supported the presence of the leukemic cells with monosomy 7 in the peripheral blood.

Fig. 2.

Profiler microsatellite analysis at loci TPOX (A–D) and D7S820 (E–H) from case 2; pre-transplant samples of patient (A and E) and donor (B and F) and post-transplant peripheral blood samples at 5 months (C and G) and 6 months (D and H). Arrows indicate the presence of recipient-specific 223 base TPOX allele in the post-transplant samples (C and D). The presence of recipient-specific 223 base TPOX allele and absence of recipient-specific 280 base D7S820 allele (▼, G and H) at 5 and 6 months is consistent with residual leukemia cells with monosomy 7.

Case 2

A 67 year-old male developed myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with monosomy 7 and other chromosomal abnormalities as demonstrated by karyotyping, 14 months after autologous HSCT for diffuse large cell lymphoma. The patient received an HLA-haploidentical non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from his sister. The pre-transplant Profiler microsatellite analyses revealed 3 informative loci for evaluation of a donor-predominant sample: TPOX (Fig. 2A and 2B), amelogenin (not shown) and D7S820 (272 and 280 bases for patient and 272 and 276 bases for donor, Fig. 2E and 2F). The ratio of the D7S820 locus in these pre-transplant patient sample and donor sample are normal. The D7S820 locus, which is located at chromosome 7q, however, was not included for chimerism calculation because of known monosomy 7 of the leukemia cells.

In the peripheral blood, the patient’s DNA comprised 10% of all DNA at 5 months post-transplant based on the calculation from the TPOX (Fig. 2C) and amelogenin locus (not shown). For the D7S820 locus, based on the presence of 10% recipient normal hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood, one would expect a recipient-specific 280 base allele with a peak height of approximately 412 RFU based on the calculation r280/(r280+d276) = 10% (r280: peak height of recipient-specific allele at 280 bases; d276: peak height of donor-specific allele at 276 bases, 3712 RFU). The STR analysis of D7S820, however, showed no 280 base peak (Fig. 2G), suggesting that the patient DNA was derived from leukemic cells with loss of the 280 base allele at locus D7S820, rather than from normal recipient cells that would be expected to carry the 280 base allele. At 6 months after transplant, there was 72% patient DNA in the peripheral blood based on the analysis of the TPOX locus (Fig. 2D), but no expected 280 base peak at D7S820 locus (Fig. 2H). Cytogenetic analysis of peripheral blood at 6 months after transplant confirmed monosomy 7 as well as other chromosomal abnormalities in 14 of the 20 cells analyzed.

Case 3

A 55 year-old female with treatment-related MDS/AML underwent HLA-haploidentical non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from her sister. The patient initially presented with a plasmacytoma followed by multiple myeloma and received radiation therapy and chemotherapy 7–8 years before the diagnosis of MDS. More recently, bone marrow biopsy showed AML evolving from MDS. Pre-transplant chimerism analysis of the peripheral blood was performed using the Identifiler kit. Multiple loci were informative, including DS21S11 (Fig. 3A and 3B). Although informative, the CSF1PO locus at chromosome 5q33.3-34 was not included for chimerism analysis because of imbalance of the two heterozygous alleles at 325 bases (peak height: 1921 RFU) and 333 bases (peak height: 3649 RFU) (ratio = 1.90; Fig. 3E), suggesting entire or partial deletion of one chromosome 5 (the 325 base allele of CSF1PO in this patient) which is common in treatment-related AML.

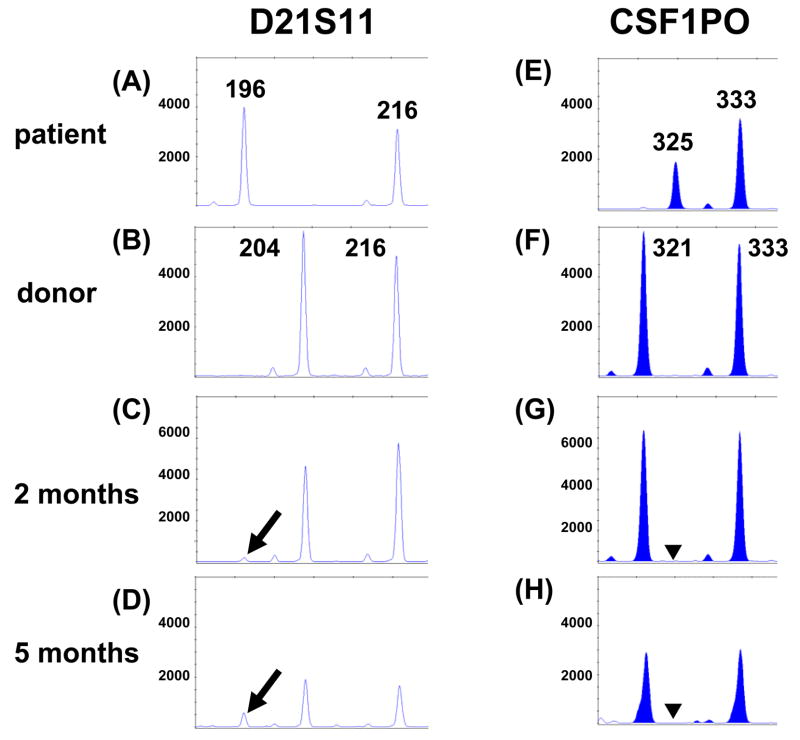

Fig. 3.

Identifiler microsatellite analysis at loci D21S11 (A–D) and CSF1PO on chromosome 5q (E–H) from pre-transplant samples of case 3 (A and E) and donor (B and F) and post-transplant peripheral blood samples at 2 months (C and G) and 5 months (D and H). Arrows indicate the presence of a recipient-specific 196 base D21S11 allele in the post-transplant samples (C and D). The presence of the recipient-specific 196 base D21S11 allele and absence of a recipient-specific 325 base CSF1PO allele (▼ in G and H) indicate persistent residual leukemia cells with monosomy 5 or 5q deletion.

At 2 months post-transplant, bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometric analysis showed normocellular marrow with no evidence of residual leukemia. FISH analysis for 5q deletion/monosomy 5 was within normal limits. Chimerism analysis of peripheral blood revealed 3% patient DNA (D21S11: 4%, D18S51: 2.1%, and FGA: 2.8%) (Fig. 3C and data not shown). Based on the calculation r325/(r325+d321) = 3% at the locus CSF1PO (p325: peak height of recipient-specific allele at 325 bases; d321: peak height of donor-specific allele at 321 bases, 6383 RFU), a peak height of approximately 197 RFU amplified from the recipient-specific 325 base allele was anticipated if all of the recipient DNA was derived from normal hematopoietic cells. The absence of the 325 base peak suggested persistent leukemic cells with deletion of the lower molecular weight patient allele (Fig. 3G). Chimerism analysis of CD3+ T cells isolated from the peripheral blood showed 77% patient DNA based on the calculation from locus CSF1PO, r325/(r325+d321) = 848/848+251, which was in agreement with an average of 72% patient DNA calculated from the other loci (data not shown). This confirmed that the genotypically abnormal population of cells resides among the non-T cell compartment, compatible with a small population of myeloid leukemia. At 5 months post-transplant, bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometric analysis confirmed the recurrence of AML. Chimerism analysis of the peripheral blood showed 26% patient DNA at locus D21S11 (Fig. 3D). However, there was no recipient-specific 325 base allele at CSF1PO (Fig. 3H), again indicating recurrence of leukemia, and consistent with the morphologic findings.

Case 4

A 37 year-old female with hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma underwent HLA-haploidentical non-myeloablative allogeneic HSCT from her brother. Cytogenetic analysis of the initial diagnostic liver and bone marrow specimens was not performed. However, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma has been consistently associated with isochromosome 7q (gain of 7q and loss of 7p).15 Bone marrow biopsy after chemotherapy, but before transplant, was negative for involvement by lymphoma. The pre-transplant Profiler microsatellite analysis revealed 2 informative loci for evaluation of donor-predominant samples, FGA (Fig. 4A and 4B) and D3S1358. The D7S820 locus located on the long arm of chromosome 7 was not informative by standard criteria since the patient and donor shared the same alleles (268 and 276 bases), and was in good balance. The peak height ratio of the 276 base and 268 base alleles was 90% for the pre-transplant patient sample (Fig. 4E) and 86% for the donor sample (Fig. 4F). Results from 10 random donors seen in our diagnostic laboratory with heterozygous 268 and 276 alleles showed an average 276/268 allele peak height ratio of 92.3% with a range of 85.9%–101.4% and a standard deviation of 5.6%. These findings are typical for STR analysis by capillary electrophoresis, which generally shows lower peak height for the allele with the longer amplicon (presumably because of slightly less efficient PCR amplification than the shorter amplicon).

Fig. 4.

Profiler microsatellite analysis at loci FGA (A–D) and D7S820 (E–H) from pre-transplant samples of case 4 (A and E) and donor (B and F) and post-transplant bone marrow sample at 6 months (C and G) and peripheral blood sample at 12 months (D and H). Arrows indicate the presence of recipient-specific 236 and 240 base alleles in the post-transplant samples (C and D). 276/268 = the peak height ratio of allele 276 to allele 268 (E, F, G and H). The increasing peak height ratio at 6 and 12 months (G and H) is consistent with gain of chromosome 7q and suggests recurrence of gamma/delta T cell lymphoma, a disease with a unique isochromosome 7q abnormality.

There was no patient DNA detected in post-transplant bone marrow samples from both the first and second months, with 276/268 allele peak height ratios of 97% and 93%, respectively. At 6 months post-transplant, the bone marrow biopsy revealed interstitial and sinusoidal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells and flow cytometric analysis identified 2.6% of CD3+CD2+CD7dim TCRγ/δ lymphocytes, suggesting recurrence of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. The microsatellite analysis showed only 18% recipient DNA in the marrow (Fig. 4C) and a 276/268 allele peak height ratio of 112% (Fig. 4G). At 12 months post-transplant, the patient had full-blown recurrence with 83% patient DNA in the peripheral blood (Fig. 4D) and a 276/268 allele peak height ratio of 175% (Fig. 4H). The reversal of the 276/268 allele peak height ratio (from less than to greater than 100%) suggests gain of the 276 base allele located at chromosome 7q and was consistent with the presence of lymphoma cells with isochromosome 7q.

Discussion

The patient specific DNA pattern may emerge post-HSCT and is indicative of relapse or recovery of the patient’s normal hematopoietic elements, results with extremely different management implications. We have presented 4 examples from our clinical service that demonstrate the ability of STR analysis in the post-HSCT setting to identify relapsed leukemia or lymphoma. This is possible whether the loci are informative or not for standard chimerism studies. The cases illustrated here are representative of a larger phenomenon: copy number variation unique to a patient’s tumor can be used to distinguish, in a transplant setting, benign patient cells from malignant patient cells.

Abnormal cytogenetic changes of chromosomes 5 and 7 are each seen in 10% of MDS and 40 and 50% of therapy-related MDS, respectively (Table 1).16 Although the informative alleles at loci CSF1PO (chromosome 5q), D5S818 (chromosome 5q) and D7S820 (chromosome 7q) would typically not be used for calculation of recipient-donor mixed chimerism in the presence of deletion of chromosomes 5 and 7, in reality these alleles may be useful for identifying leukemic relapse. Other common chromosomal abnormalities of AML/MDS involving loci used in the AmpFlSTR Identifiler kit include 3p deletion (D3S1358), trisomy 8 (D8S1179), 12p deletion (vWA), 13q deletion (D13S317), monosomy 18 (D18S51), monosomy 21 (D21S11) and deletion of chromosome Y (amelogenein) (Table 1).17,18 A comprehensive cytogenetic analysis or microarray analysis is needed for patients with MDS or leukemia to identify chromosomal abnormalities at the initial presentation.

Microsatellite analysis is not very sensitive in detecting minimal residual leukemia cells compared to RT-PCR for cancer-specific translocations. However, the sensitivity compares favorably to those of morphology, cytogenetics and even flow cytometry. In cases 1–3, we have shown that loss of chromosomes 5/5q or 7/7q in leukemia cells, as demonstrated by microsatellite analysis, can prove that patient DNA in post-transplant bone marrow or peripheral blood is derived from leukemia cells. In the early post-transplant setting of cases 1 and 3, bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometry did not detect increased or phenotypically abnormal blasts, while the abnormal chimerism pattern was indicative of early relapse. In case 1, bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometric analysis showed no evidence of residual leukemia at one month after transplantation. However, the presence of 8% patient DNA with absence of the recipient-specific 263 base allele at locus D7S820 indicated persistent leukemia with monosomy 7 or 7q deletion. This was confirmed by FISH showing 5.2% cells with monosomy 7 or 7q deletion. In case 3, bone marrow biopsy and flow cytometry analysis showed no evidence of residual leukemia at 2 months after transplantation. The presence of 3% patient DNA with absence of the recipient-specific 325 base allele at locus CSF1PO suggested persistent leukemia with monosomy 5 or 5q deletion. FISH analysis for 5q deletion/monosomy 5 was within the normal limits (normal cutoff for monosomy: <2.5% and for 5q deletion: <3.5%). This patient had overt clinical recurrence at 5 months post-transplant.

Case 4 demonstrated a different concept. The patient and donor shared two alleles at D7S820 and would not be considered informative for standard chimerism analysis. However, because of a copy number change (presumably due to isochromosome 7q, although this was not proved cytogenetically), the ratio of the 2 alleles became meaningful diagnostically. The divergence of one peak height ratio from others (in case 4, the increase at D7S820 relative to the peak height ratios of FGA and D3S1358) served as a marker for tumor cells with a copy number alteration at that locus. This approach relies upon the stability and comparability of peak height ratios at specific loci across patients, which we have recently demonstrated.19 We used this finding to detect the recurrence of gamma/delta T cell lymphoma, but in theory all malignancies showing a loss or gain of material at an appropriate locus could be identified.

There are several pitfalls in interpretation that these cases illustrate. In cases 1–3, the absence of an expected peak was used as evidence that the patient’s DNA is derived from cancer cells. However, amplification for each locus in multiplex PCR is always not equally efficient. Thus, allele dropout may occur when the input DNA is low and/or the DNA is severely degraded yielding a pattern that indicates apparent, but artifactual, loss of an allele. Longer electroinjection for capillary electrophoresis may be needed to correct this if the amplification of the informative locus is relatively poor and repeated PCR may be needed to confirm the copy number variation. In case 4, the evidence for persistent cancer cells is based on the interpretation of copy number variation due to gain of an allele in cancer cells. However, the amplification efficiency varies depending on the size difference between the two heterozygous alleles. A collection of data from normal samples with the same genotype at this locus is needed to define the range and standard deviation of the peak height ratio.

In summary, discrepancy of the calculated percentage of chimerism between informative loci may suggest the presence of DNA derived from cancer cells with copy number variation and, therefore, indicate residual malignant disease. STR loci with gain or loss of an allele, although not suitable for analysis of mixed chimerism, can be useful in indicating residual or recurrent malignancy. We suggest that a targeted evaluation of “uninformative” loci when performing a post-transplant mixed chimerism study can provide evidence of residual cancer cells. We also recommend that the report for post-transplant chimerism analysis include comments about variation from normal allele ratios: e.g., “the presence of copy number variation at the tested locus is consistent with the patient’s known cytogenetic abnormality, suggesting persistent or recurrent leukemia/lymphoma”.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number R21HG004315 from NHGRI/NIH to CDG.

References

- 1.Thiede C, Florek M, Bornhauser M, et al. Rapid quantification of mixed chimerism using multiplex amplification of short tandem repeat markers and fluorescence detection. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:1055–1060. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nuckols JD, Rasheed BK, McGlennen RC, et al. Evaluation of an automated technique for assessment of marrow engraftment after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation using a commercially available kit. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:135–140. doi: 10.1309/QP7P-J49V-8Q15-36MT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antin JH, Childs R, Filipovich AH, et al. Establishment of complete and mixed donor chimerism after allogeneic lymphohematopoietic transplantation: recommendations from a workshop at the 2001 Tandem Meetings of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:473–485. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11669214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan F, Agarwal A, Agrawal S. Significance of chimerism in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: new variations on an old theme. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34:1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bader P, Holle W, Klingebiel T, et al. Mixed hematopoietic chimerism after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: the impact of quantitative PCR analysis for prediction of relapse and graft rejection in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:697–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roman J, Martin C, Torres A, et al. Importance of mixed chimerism to predict relapse in persistently BCR/ABL positive long survivors after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;28:541–550. doi: 10.3109/10428199809058362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Leeuwen JE, van Tol MJ, Joosten AM, et al. Persistence of host-type hematopoiesis after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for leukemia is significantly related to the recipient’s age and/or the conditioning regimen, but it is not associated with an increased risk of relapse. Blood. 1994;83:3059–3067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molloy K, Goulden N, Lawler M, et al. Patterns of hematopoietic chimerism following bone marrow transplantation for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia from volunteer unrelated donors. Blood. 1996;87:3027–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiede C, Bornhauser M, Ehninger G. Strategies and clinical implications of chimerism diagnostics after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Haematol. 2004;112:16–23. doi: 10.1159/000077555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Childs R, Clave E, Contentin N, et al. Engraftment kinetics after nonmyeloablative allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: full donor T-cell chimerism precedes alloimmune responses. Blood. 1999;94:3234–3241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou M, Sheldon S, Akel N, et al. Chromosomal aneuploidy in leukemic blast crisis: a potential source of error in interpretation of bone marrow engraftment analysis by VNTR amplification. Mol Diagn. 1999;4:153–157. doi: 10.1016/s1084-8592(99)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schichman SA, Suess P, Vertino AM, et al. Comparison of short tandem repeat and variable number tandem repeat genetic markers for quantitative determination of allogeneic bone marrow transplant engraftment. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:243–248. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swierczynski SL, Hafez MJ, Philips J, et al. Bone marrow engraftment analysis after granulocyte transfusion. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:422–426. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin MT, Rich RG, Shipley RF, et al. A molecular fraction collecting tool for the ABI 310 automated sequencer. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:598–603. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang CC, Tien HF, Lin MT, et al. Consistent presence of isochromosome 7q in hepatosplenic T gamma/delta lymphoma: a new cytogenetic-clinicopathologic entity. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;12:161–164. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jotterand M, Parlier V. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of cytogenetics in adult primary myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;23:253–266. doi: 10.3109/10428199609054828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauritzson N, Albin M, Rylander L, et al. Pooled analysis of clinical and cytogenetic features in treatment-related and de novo adult acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes based on a consecutive series of 761 patients analyzed 1976–1993 and on 5098 unselected cases reported in the literature 1974–2001. Leukemia. 2002;16:2366–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preiss BS, Bergman OJ, Friis LS, et al. AML Study Group of Southern Denmark: Cytogenetic findings in adult secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML): frequency of favorable and adverse chromosomal aberrations do not differ from adult de novo AML. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;202:108–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silzle E, Shane RM, Rich RG, et al. Reference intervals for microsatellite loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in brain tumor biopsies. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:613a. [Google Scholar]