Abstract

Chronic pain hypersensitivity depends on N-type voltage-gated calcium channels (CaV2.2). However, the use of CaV2.2 blockers in pain therapeutics is limited by side effects that result from inhibited physiological functions of these channels. Here we report suppression of both inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity by inhibiting the binding of the axonal collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2) to CaV2.2, thus reducing channel function. A 15-amino acid peptide of CRMP-2 fused to the transduction domain of HIV TAT protein (TAT-CBD3) decreases neurotransmitter release from nociceptive dorsal root ganglion neurons, reduces meningeal blood flow, reduces nocifensive behavior induced by subcutaneous formalin injection or following corneal capsaicin application, and reverses neuropathic hypersensitivity produced by the antiretroviral drug 2’,3’-dideoxycytidine. TAT-CBD3 was mildly anxiolytic but innocuous on sensorimotor and cognitive functions and despair. By preventing CRMP-2-mediated enhancement of CaV2.2 function, TAT-CBD3 alleviates inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity, an approach that may prove useful in managing clinical pain.

Individuals suffering from nerve injury or those undergoing treatment for cancer or AIDS can experience persistent pain that may be refractory to opioids and which necessitates the use of intrathecal drug treatments for pain management1, 2. For conditions of chronic intractable clinical pain, intrathecal delivery of Prialt, a synthetic ω-conotoxin that blocks neuronal calcium channels, has been approved by the FDA, thus identifying the N-type Ca2+ channel (CaV2.2) as a critical target for treatment of chronic pain3-6. However, use of Prialt for pain management is limited by its method of delivery, narrow therapeutic window, and adverse effects such as hypotension and memory loss3, 6, thus underscoring the need for better inhibitors of calcium channels.

Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain represents a novel route of drug discovery. Voltage-gated calcium channels are multiprotein complexes comprised of a pore-forming α-subunit and auxiliary α2/δ, β, and γ subunits7, 8. Within the Ca2+ channel complex, we recently identified the collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2) as a novel modulator of CaV2.29, 10. CRMP-2 is a cytosolic phosphoprotein originally identified as a mediator of semaphorin3A induced growth cone collapse11 and can modify axon number and length12 and neuronal polarity13-15. We determined that CRMP-2 interacts with CaV2.2 and that overexpression of CRMP-2 leads to increased surface expression of CaV2.2 and enhanced Ca2+ currents9, 10. CRMP-2 overexpression also increases stimulated release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) from dorsal root ganglia (DRG)10. In contrast, knockdown of CRMP-2 dramatically reduces Ca2+ currents and transmitter release9, 10. These findings suggest that the biochemical interaction between CRMP-2 and CaV2.2 is required for proper channel trafficking and function. We tested the hypothesis (Fig. 1a) that uncoupling the CRMP-2–CaV2.2 interaction would lead to a physiologically relevant decrease in Ca2+ current and neurotransmitter release and, in turn, suppress persistent inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity.

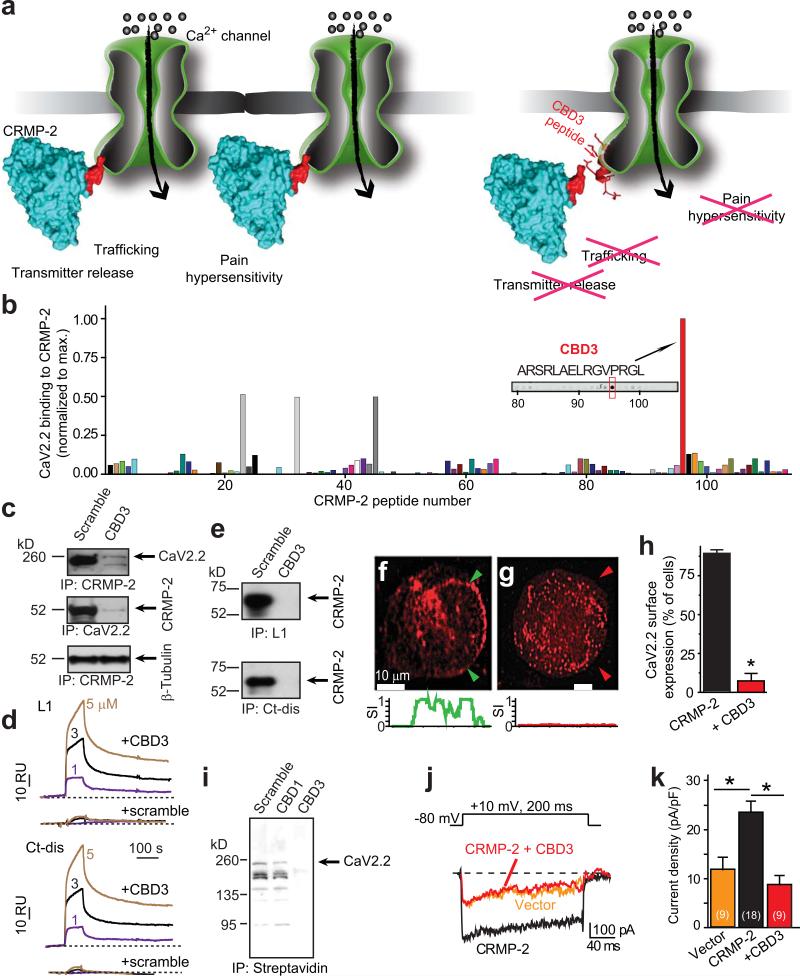

Figure 1.

A CRMP-2 peptide suppresses the CaV2.2-CRMP-2 interaction in vitro. (a) Cartoon illustrating the main hypothesis. (b) Summary of normalized binding of CaV2.2 to 15 amino acid peptides (overlapping by 12 amino acids) encompassing full-length CRMP-2 overlaid with spinal cord lysates. Sequence of peptide #96, designated CBD3, is shown. (c) Immunoprecipitation (IP) with CRMP-2 antibody from spinal cord lysates in the presence of scramble or CBD3 peptides failed to pull-down CaV2.2 (top) and CRMP-2 (middle) but not β-tubulin (bottom). (d) Sensorgram of CBD3 (1/3/5 μM; solid traces) or scramble peptide (1/3/5 μM; dotted traces) binding to immobilized cytosolic loop 1 (L1) and distal C-terminus (Ct-dis) of CaV2.2. Dissociation was monitored for 4 min. RU, resonance units. (e) In vitro binding of L1-GST and Ct-dis-GST fusion proteins to CRMP-2 in the presence of scramble or CBD3 peptides (10 μM). CRMP-2 bound to L1 and Ct-dis was probed with a CRMP-2 antibody. CaV2.2 is detected on the surface of CAD cells (f) but not when CBD3 fused to GFP is over-expressed (g). Below, normalized surface intensity (SI) between arrows demarcating the surface of cells shown in f and g. (h) Summary of the percent of cells exhibiting surface CaV2.2 expression (n>100). (i) Immunoblots of biotinylated (surface) fractions of CAD cells expressing vector (scramble), an N-terminal region of CRMP-2 (CBD1), or CBD3 probed with a CaV2.2 antibody (n=3). (j) Top, voltage protocol. Bottom, exemplar traces from hippocampal neurons overexpressing vector (EGFP), CRMP-2 or CRMP-2 + CBD3. (k) Peak current density (pA/pF), at +10 mV, for CRMP-2- and CRMP-2 + CBD3-transfected neurons. *, p <0.05 versus CRMP-2, Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Identification and in vitro characterization of a CRMP-2–Ca2+ channel uncoupling peptide

To develop a reagent to disrupt the interaction of CRMP-2 with the CaV2.2 complex in vivo, we synthesized a series of overlapping 15-amino-acid peptides covering the entire length of CRMP-2, including three CaV binding domains (CBDs1–3) we had previously identified in vitro as crucial for the CRMP-2–CaV2.2 interaction9. We found that a peptide consisting of amino acids 484-498 of CRMP-2, CBD3, bound to CaV2.2 (Fig. 1b). Immunoprecipitations from spinal cord lysates demonstrated that CBD3 peptide inhibited the interaction between CRMP-2 and CaV2.2 (Fig. 1c; top, middle) but did not affect the interaction between tubulin and CRMP-216 (Fig. 1c, bottom). Since we previously reported that CRMP-2 binds to the first intracellular loop (L1) and the end of the C-terminus (Ct-dis)9, we next investigated whether CBD3 bound to these regions. Using surface plasmon resonance, we determined that CBD3 peptide, but not a scramble peptide, bound to immobilized L1 and Ct-dis proteins (Fig. 1d). Moreover, the CBD3 peptide disrupted the interaction between CRMP-2 and the intracellular loop 1 (L1) or a distal part of the C-terminus (Ct-dis) regions of CaV2.2 in vitro: CBD3, but not the scramble peptide, caused a dramatic reduction in ability of L1 or Ct-dis proteins to pull down CRMP-2 (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1).

Because CRMP-2 facilitates surface trafficking of CaV2.29, 10, we tested if CBD3 could uncouple CRMP-2 from CaV2.2 to affect (a) trafficking, (b) surface expression, (c) CaV2.2 activity, and (d) Ca2+ influx. Co-expression of CaV2.2 with CBD3 in the CAD neuronal cell line resulted in almost complete retention of the channel in cytoplasmic aggregates (Fig. 1f-h). Surface biotinylation experiments in CAD cells showed that expression of CBD3, but not scramble or CBD1, a region encompassing 73 amino acids in the N-terminus of CRMP-2, prevented surface expression of co-expressed CaV2.2 (Fig. 1i). Consistent with these results, co-expression of CRMP-2 with CBD3 in hippocampal neurons eliminated the CRMP-2-mediated increase in CaV2.2 current density (Fig. 1j, k)9. Furthermore, expression of plasmids harboring CBD3, but not a scramble control, reduced depolarization-induced calcium influx in hippocampal and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c). Thus, in vitro, CBD3 disrupts the CRMP-2-CaV2.2 interaction and affects CaV2.2 trafficking and Ca2+ current density.

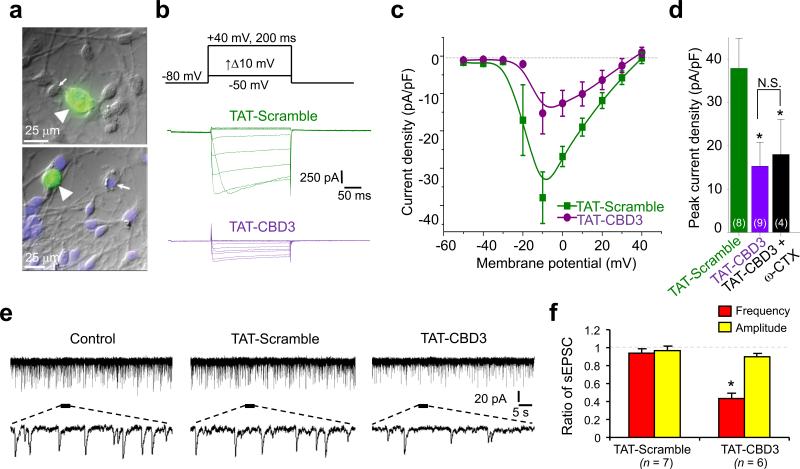

Since CBD3 is not cell permeant, we fused it to the protein transduction domain of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) transactivator of transcription (TAT) protein17, generating TAT-CBD3 which readily entered neurons (Fig. 2a). A 15 min application of TAT-CBD3 to DRGs reduced Ca2+ currents by ~60% which were not further blocked by addition of the CaV2.2 blocker ω-conotoxin (1 μM) (Fig. 2c, d), suggesting selectivity of TAT-CBD3 for N-type channels. Qualitatively similar results were obtained from Fura-2 Ca2+ imaging experiments in DRGs: CBD3 reduced K+-evoked Ca2+ influx selectively through N-type Ca2+ channels (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Importantly, TAT-CDB3 did not affect Na+ current density or gating in DRGs (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

TAT-CBD3 reduces Ca2+ currents in DRGs and synaptic responses in lamina II neurons from spinal cord slices. (a) Representative differential interference contrast/fluorescence images showing robust penetration of FITC-TAT-CBD3 into DRGs (arrowheads) but not other cells (arrows). (b) Representative current traces from a DRG incubated for 15 min with TAT-Scramble (10 μM; green) or TAT-CBD3 (10 μM; purple) in response to voltage steps illustrated above the traces. (c) Current-voltage relationships for the currents shown in b fitted to a b-spline line. Peak currents were normalized to the cell capacitance. (d) Peak current density (pA/pF) measured at –10 mV for DRGs incubated with TAT-Scramble, TAT-CBD3 or TAT-CBD3 + 1 μM ω-CTX. The numbers in parentheses represent numbers of cell tested. *, p<0.05 versus TAT-Scramble. (e) Representative traces of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) in lamina II neurons in spinal cord slices before treatment (left traces), after application of 10 μM TAT-Scramble peptide (middle traces) or 10 μM TAT-CBD3 peptide (right traces). Lower panels are enlarged traces. Voltage-clamp recordings (holding voltage = –70 mV) were used to record synaptic responses. (f) Ratio of sEPSC frequency and amplitude. *, p < 0.05, compared with baseline. Note the significant decrease in the frequency but not amplitude of sEPSCs after the application of TAT-CBD3 peptide.

Next, to determine if uncoupling CRMP-2 from CaV2.2 with TAT-CBD3 modulates synaptic transmission, we used spinal cord slice recording techniques to measure synaptic responses from lamina II neurons (Fig. 2e, f), which express CaV2.218. Perfusion of spinal cord slices with TAT-CBD3 reduced the frequency, but not amplitudes, of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs), supporting a presynaptic action of the peptide (Fig. 2f). Recordings from layer V pyramidal neurons, which express CaV2.219, 20, showed that TAT-CBD3 significantly decreased amplitude of eEPSCs, predominantly by acting on N-type channels, suggesting a decrease in excitatory synaptic transmission to these neurons(Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, the TAT-Scramble peptide had no effect on the amplitude of eEPSCs. Furthermore, TAT-CBD3 significantly increased pair pulse ratios, calculated by dividing eEPSC amplitude elicited by a second pulse from that of the first pulse, (Supplementary Fig. 4c), suggesting a reduction in release probability of glutamate from the stimulated presynaptic terminals21.

TAT-CBD3 reduces evoked transmitter release from isolated sensory neurons and spinal cord slices

CaV2.2 is expressed on the presynaptic terminals of small diameter sensory neurons22 and calcium entry through this channel results in transmitter release7, 23. We recently showed that CRMP-2 expression levels impact release of the neuropeptide transmitter, CGRP, in sensory neurons10. Consequently, we investigated whether the actions of TAT-CBD3 could affect sensory neurotransmission. To determine if perturbing the CRMP-2–CaV2.2 interaction with the TAT-CBD3 peptide can modulate transmitter release, resting and potassium-stimulated release of immunoreactive CGRP (iCGRP) was measured from supernatants of DRG neurons in culture that were treated with 10 μM TAT-CBD3 or TAT scramble. Pretreatment with TAT-CBD3, but not TAT-Scramble, for 12 h or 20 min reduced CGRP release evoked by 50 mM potassium chloride, but did not affect resting release (Supplementary Fig. 5). Furthermore, total CGRP content (i.e. the sum of iCGRP released during the experiment and the remaining CGRP in the cells) in the cultures was unaffected by the peptides. Cell viability, measured after the 12 h treatment, was not affected by any of the treatments (Supplementary Fig. 6).

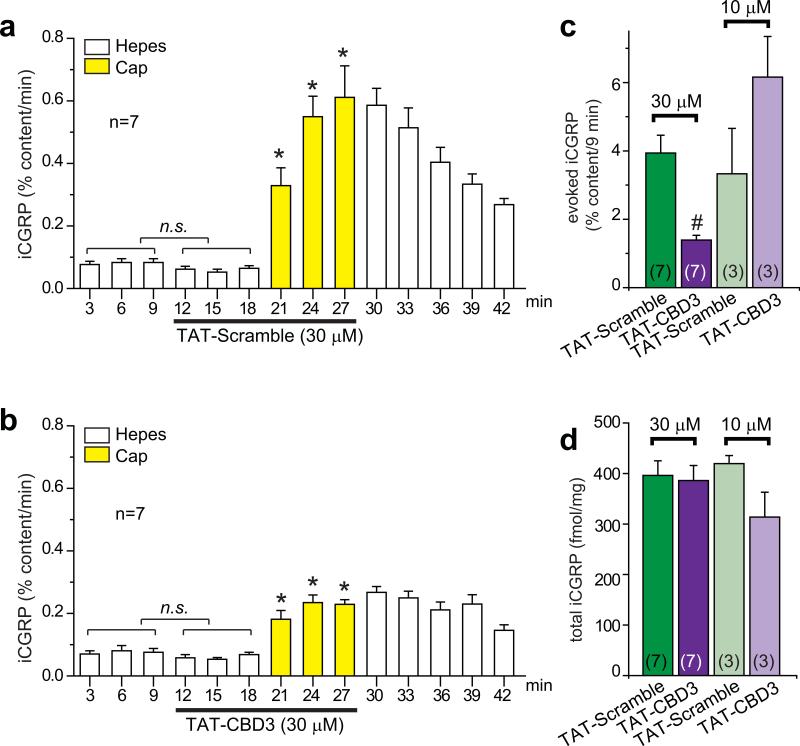

To further examine the effect of TAT-CBD3 on transmitter release from sensory neurons, capsaicin-evoked CGRP release was measured from spinal cord slices. Release from spinal cord slices occurs primarily from central terminals of neurons that express a capsaicin-, low pH- and heat-activated ion channel, the transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) channel24 which has been shown to be important in pain signal propagation. Perfusion with TAT-Scramble or TAT-CBD3 peptides did not change basal iCGRP release from spinal cord slices (Fig. 3a, b), consistent with iCGRP release from DRG neurons in culture (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, perfusion with 30 μM, but not 10 μM, TAT-CBD3 led to a significant decrease in capsaicin-stimulated CGRP release compared to TAT-Scramble (Fig. 3c) with no differences in iCGRP total content (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

TAT-CBD3 peptide reduces capsaicin-stimulated release of iCGRP from spinal cord slices. iCGRP release from spinal cord slices stimulated by three 3-min exposures to Hepes buffer alone (white bars) or Hepes buffer containing 500 nM capsaicin (yellow bars) is expressed as mean percent total peptide content of iCGRP in the spinal cord slice±SEM (n=3–7 animals per condition). TAT-Scramble (a) or TAT-CBD3 (b), at 30 μM or 10 μM, was included in the six 3-min incubations indicated by lines, for a total exposure time of 18 min. *, p < 0.05 versus basal iCGRP release in the absence of capsaicin using an ANOVA with a Dunnett's post-hoc test. TAT-Scramble or TAT-CBD3 did not affect basal release of iCGRP (not significant; n.s.). For clarity, only the time course for the 30 μM experiments is shown. (c) Evoked release is compared between TAT treatments. The evoked release was obtained by subtracting iCGRP release during three basal fractions from that during the three capsaicin-stimulated fractions in each treatment group. In all cases, release stimulated by capsaicin was significantly higher than basal release. #, p < 0.05 versus TAT-Scramble using a Student's t-test. (d) Total content of iCGRP released during the perfusion and the amount remaining in the tissues measured at the end of the release experiments.

TAT-CBD3 reduces capsaicin-evoked vasodilatation in the rat dura mater in vivo

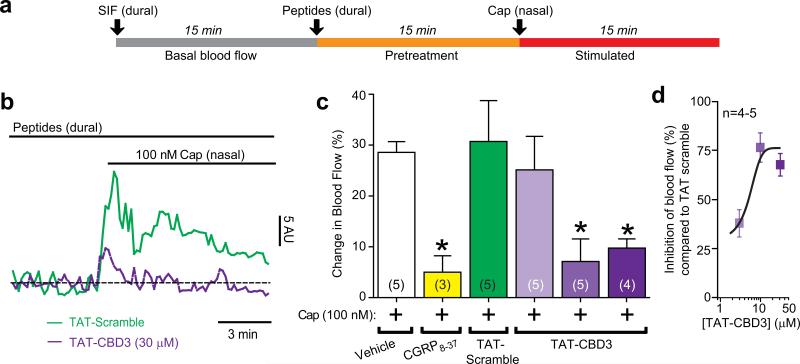

The dura mater is innervated by trigeminal capsaicin-sensitive peptidergic nociceptive afferent nerves which mediate meningeal vascular responses related to headache pain25. The role of CGRP released by sensory fibers in headache and chronic migraine has recently been highlighted by clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of CGRP antagonists26. Since we reported the involvement of calcium channels27 and CRMP-210 in CGRP release, we consequently tested the potential involvement of the CRMP-2 in vasodilatation in the rat dura. This animal model of migraine uses in vivo laser Doppler blood flowmetry to assay blood flow changes in the meninges in response to chemical or electrical stimulation of trigeminal neurons. Measurements of meningeal blood flow represent a strong and accepted physiological marker of headache symptoms in rodent models28. Trigeminal nerve activation in this preparation induces meningeal blood vessel dilatation which is CGRP-dependent 29. Capsaicin induced a rapid and robust increase in meningeal blood flow (Fig. 4b) which returned toward baseline values within minutes. Dural application of TAT-CBD3 prior to nasally administered capsaicin significantly inhibited the capsaicin-induced blood flow changes in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4c, d). There was no effect of TAT-CBD3 administration alone on basal blood flow: Δblood flow was -6 ± 1, n=5 (vehicle), -4 ± 3, n=4 (TAT-CBD3), and -9 ± 3, n=5 (TAT-Scramble; where Δblood flow = blood flow3 min before peptide – blood flow3min after peptide).

Figure 4.

TAT-CBD3 reduces meningeal blood flow changes in response to capsaicin. (a) Experimental paradigm for the Laser Doppler flowmetry measurements. (b) Representative normalized traces of middle meningeal blood flow changes in response to nasally administered capsaicin (Cap, 100 nM) in the presence of TAT-Scramble (30 μM, green trace) or TAT-CBD3 pretreatment (30 μM, purple trace, applied durally 15 minute prior to Cap administration). Laser Doppler flowmetry measurements were collected at 1 Hz and binned by averaging every 10 samples for graphical representation. The data from each animal was normalized to the first 3 minutes of basal data and the horizontal dashed line indicates the calculated baseline. The ordinate represents red blood cell flux measurements in arbitrary units (AU). (c) Summary of blood flow changes following nasal administration of Cap in the absence or presence of previous administration of TAT-CBD3 or TAT-Scramble to the dura. The capsaicin-induced blood flow changes were CGRP-dependent as they could be blocked by prior dural administration of the CGRP antagonist, CGRP8-37. Values are mean ± S.E.M. *, p < 0.05 versus vehicle (unpaired Student's t-test). The number of animals tested for each condition is indicated in parentheses. (d) Dose response curve of percent inhibition (versus averaged TAT-scramble) of blood flow yields an IC50 of 3.1 ± 1.1 μM (n=4-5).

TAT-CBD3 does not affect capsaicin-evoked TRPV1 currents in DRG neurons

Since capsaicin-evoked iCGRP release is mediated through the TRPV1 channel24, we next investigated the possibility that the effect of TAT-CBD3 on CGRP release was due to inhibition of the TRPV1 channel. Currents were recorded from isolated DRG neurons, neurons where we have previously shown a functional coupling between CRMP-2 and CaV2.210. Isolated neurons exposed to TAT-CBD3, administered via the recording pipette or overnight in the cell culture medium, exhibited no significant differences in capsaicin-evoked current density at -60 mV (Supplementary Fig. 7). This is an important negative control, because the lack of a direct effect of TAT-CBD3 on TRPV1 current demonstrates that the inhibitory actions of TAT-CBD3 on capsaicin-evoked neurotransmitter release and dural blood flow are not via direct inhibition of TRPV1 channels, a non-selective cation channel.

TAT-CBD3 reduces formalin-induced nocifensive behavior

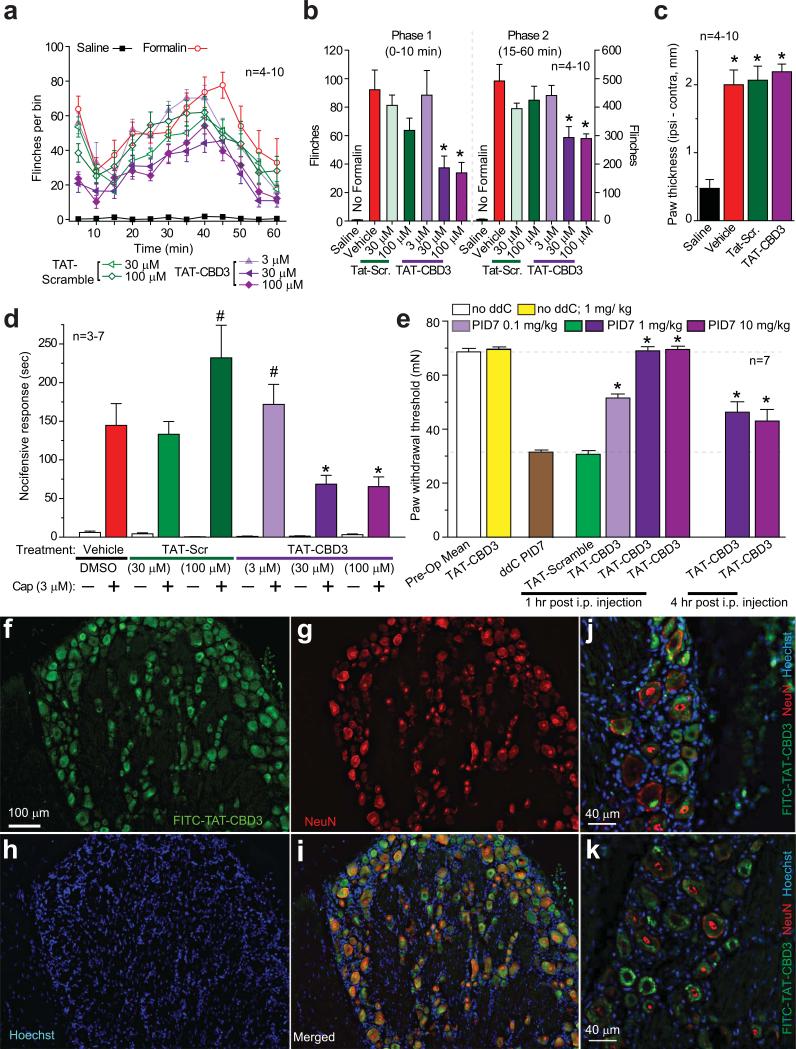

Since inhibiting CaV2.2 is antinociceptive30, we next examined whether the TAT-CBD3 peptide could attenuate nociceptive responses in several animal models of pain. We first examined the effects of TAT-CBD3 and TAT-scramble peptides on formalin-induced nocifensive behavior. In rats administered a subcutaneous injection (to dorsal surface of paw) of vehicle (20 μl 0.5% DMSO) 30 minutes prior to injection of formalin (2.5% in 50 μl) in the hindpaw, we observed the expected biphasic formalin response31 (Fig. 5a). Immediately after injection of formalin, the animals displayed a high degree of flinching (phase 1) which lasted about 10 minutes followed by a second period of flinching (phase 2) which subsided by 60 minutes. Pretreatment with 30 or 100 μM TAT-Scramble did not significantly change either phase of the formalin test. Animals injected with 30 or 100 μM TAT-CBD3 peptide displayed blunted nociceptive behaviors in both phases (Fig. 5a, b), suggesting that the peptide inhibits nociception mediated by direct activation of the sensory neurons (phase 1) and, to some extent, nociception associated with inflammation32 and possible spinal involvement (phase 2)33, 34. Pretreatment with 3 μM TAT-CBD3 did not affect the formalin-induced behavior (Fig. 5a, b). Injection of the TAT peptides by itself, before the formalin injection, did not induce any nocifensive behavior. Formalin (2.5%) produced a 4-fold change in the paw thickness compared to saline injected animals (Fig. 5c), consistent with the edema typically observed following inflammation. TAT-CBD3 peptide did not inhibit the formalin-induced edema.

Figure 5.

TAT-CBD3 reduces inflammatory and antiretroviral toxic neuropathic pain. (a) Time course of number of flinches following subcutaneous (dorsal surface of the paw) injection of formalin (2.5% in 50 μl saline) in animals pretreated with TAT-Scramble or TAT-CBD3 (3–100 μM; 20 μl dorsal surface of paw) 30 min before formalin (n=4–10). (b) The effect of TAT-Scramble or TAT-CBD3 on the total number of flinches in formalin-induced phase 1 (0-10 min; left) and phase 2 (15-60 min; right). *, p <0.05 versus formalin-injected animals. (c) Formalin (2.5%) induces paw edema. Paw thickness was measured 1h after injection of saline, formalin, and formalin + TAT peptides (100 μM). *, p <0.05 versus saline- injected animals. (d) Pretreatment with TAT-CBD3 peptide attenuates capsaicin-evoked nocifensive behavior. Vehicle (0.3% DMSO), TAT scramble (30–100 μM), or TAT-CBD3 (3–100 μM) in saline (40 μL) was applied in the right eye and nocifensive behavior was noted. Five minutes after treatment, capsaicin (Cap, 3 μM in 40 μL saline) was applied in the right eye and nocifensive behavior was noted by observers blinded to treatment condition. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3-7 per group; *, p<0.05 versus vehicle, ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test). (e) Dose-dependent effect of TAT-CBD3 peptide on ddC-induced decreases in paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) in the rat at 1 h and 4 h post injection. Animals subjected to a single ddC injection exhibited a decrease in PWT that was abolished by i.p. administration of TAT-CBD3 peptide on post-injection day 7 (PID7). Data represent means ± S.E.M.; *, p < 0.05 versus ddC or TAT-Scramble (ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test), n = 6 per condition. (f-k) DRGs were isolated 15 min post-injection with 20 mg/kg FITC-TAT-CBD3, cryosectioned, and subjected to immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal anti-NeuN antibody. TAT-CBD3 (f, green, FITC) accumulates in almost all neurons with the DRG. Neurons are indicated by NeuN (g, red). Nuclei of all cells are stained with Hoechst (h, blue). Merged images are shown in i-k. Scale bars, 100 μm (f-i); 40 μm (j-k).

TAT-CBD3 attenuates capsaicin-evoked nocifensive behavior

In Figures 3 and 4, we demonstrate that TAT-CBD3 attenuates capsaicin-induced release of iCGRP from the spinal cord and increases in dural blood flow, respectively. To determine whether TAT-CBD3 has similar inhibitory effects on capsaicin-induced nociception, we utilized the capsaicin eye-wipe test. The cornea is a specialized tissue innervated by trigeminal afferent nerves, of which approximately 25% express TRPV135, 36. Application of noxious substances to the eye induces a transient nocifensive response in awake animals which can be reversed by either peripherally or systemically administered antinociceptives37-39. Thus, it is a good model for determining the antinociceptive effect of peripherally administered TAT-CBD3 peptide on acute trigeminally-mediated nociception. Application of the TAT-CBD3 peptide alone to the cornea did not induce nocifensive behavior. A 30 min pretreatment with 30 or 100 μM TAT-CBD3 peptide significantly attenuated the nocifensive behavior induced by capsaicin instillation (Fig. 5d), suggesting that the TAT-CBD3 peptide is antinociceptive at a peripheral site of action. Pretreatment with 3 μM TAT-CBD3 did not affect the nocifensive behavior; however 100 μM TAT-Scramble peptide showed a non-specific effect, increasing the nocifensive response time (Fig. 5d).

TAT-CBD3 reverses ddC-induced neuropathic pain behavior

Above, we demonstrate that TAT-CBD3 pretreatment inhibits acute and inflammatory nociception. We next examined the effects of the peptide on established chronic nociceptive behavior in an animal model of AIDS therapy-induced painful neuropathy. Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), commonly used for AIDS treatment, are known to produce serious adverse side-effects including painful neuropathies. As the NRTI 2',3'-dideoxycytidine (ddC) and other anti-retroviral nucleoside analogs are thought to alter regulation of intracellular calcium, we evaluated whether TAT-CBD3 peptide could reverse nociceptive behavior in this animal model40, 41. The ability of TAT-CBD3 and TAT-Scramble peptides to reverse tactile hypersensitivity was evaluated in rats seven days after a single injection of ddC. TAT-CBD3 alone had no effect on paw withdrawal threshold. We found that TAT-CBD3 peptide, but not TAT-Scramble peptide, caused a dose-dependent increase in paw withdrawal threshold when administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) (Fig. 5e). Complete reversal of tactile hypersensitivity was observed at the 1 mg/kg dose 1 h after i.p. injection. Four hours after injection, the TAT-CBD3 effect had diminished to ~50% in the reversal of hypersensitivity, which may be accounted for by peptide degradation and/or kinetics and tissue distribution of the peptide42. To explore the sites of distribution of the peptides after i.p. injection, we collected tissue samples from animals injected with FITC-TAT-CBD3 peptide. Within 15 min after the injection the peptide was detected in the DRG (Fig. 5f-k) and spinal cord (see Fig. 6e-h) while 1 h following the injection, the peptide was also observed in the brain (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Figure 6.

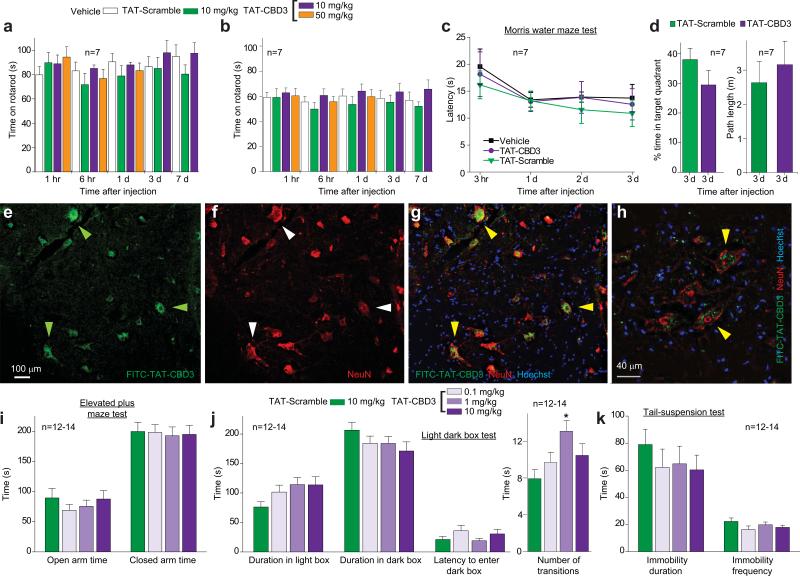

TAT-CBD3 has no effects on sensorimotor and cognitive functions and despair but is mildly anxiolytic. (a, b) Time course of latency to fall off a rod rotating at a slow (a) or fast (b) acceleration at various time points after i.p. administration of 10 mg/ kg or 50 mg/kg peptides as indicated or vehicle (n=7 each). There were no significant differences in both low and fast accelerating rotarod performances between groups (ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test). (c) Time course of latency (in sec) for mice to successfully find a hidden platform in the Morris water maze at several time points follow i.p. administration of 10 mg/kg peptides or vehicle (n=7). (d) Percent time in target quadrant and path length performance in the Morris water maze test. The platform was removed after the last day of hidden platform testing and mice were placed in the pool for a single 60-sec trial. There were no significant differences in percent time spent in target quadrant or path length between groups (Student's t-test). (e-h) Immunohistochemistry in dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Spinal cord was isolated 15 min post-injection with 20 mg/kg FITC-TAT-CBD3, cryosectioned, and subjected to immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal anti-NeuN antibody. TAT-CBD3 (e, green, FITC) accumulates in motor neurons (arrowheads) which co-label with NeuN (f, red). Nuclei of all cells are stained with Hoechst (blue). Merged images demonstrate co-labeling of FITC-TAT-CBD3-containing neurons (green) with NeuN (red) and Hoescht (blue) at low (g) and high magnification (h). Scale bars, 100 μm (e-g); 40 μm (h). (i) Elevated plus maze test to evaluate anxiety-associated behaviors. Neither the time spent in the open (F(3,48)=0.6, p=0.625) or closed (F(3,48)=0.04, p=0.987) arm, nor the frequency of entries into the (F(3,48)=1.3, p=0.282) or closed (F(3,48)=1.5, p=0.219) arms were altered by any of the 3 doses of TAT-CBD3, compared to the TAT-Scramble. (j) Light dark box test for anxiety-associated behaviors. TAT-CBD3 did not alter time spent in the light box compared to the dark box or aversion to first entering the dark box. The number of transitions between the light and dark box was increased with 1 mg/kg dose of TAT-CBD3 (F(3,47) =3.6, p=.020, *). (k) Tail suspension test of depression or despair-associated behaviors. Duration and frequency of immobility was not altered by i.p. injection of TAT-CBD3. Data reflect mean ± SEM.

Thus, our results indicate that using TAT-CBD3 which interferes with CaV2.2 and CRMP-2 interactions can reduce inflammatory and neuropathic pain behaviors.

TAT-CBD3 has no effects on sensorimotor and cognitive functions and despair but is mildly anxiolytic

We investigated the possible side-effects of TAT-CBD3 on motor coordination, locomotor function, and sedation (rotarod test of fore- and hind-limb motor dysfunction43, 44) and hippocampal-dependent memory and learning (Morris water-maze test45, 46). Impaired locomotor function did not account for the reduced flinching and paw withdrawal as TAT-CBD3 (10 and 50 mg/kg; i.p.) had no effect in the accelerating rotarod test (Fig. 6a, b). TAT-CBD3 (10 mg/kg; i.p) did not affect coordination or learning and memory at 1 h –7 d after administration (Fig. 6c, d). Transient lordosis-like contortions and kinking at the base of the tail were observed in the animals immediately following injection of higher doses (10 and 50 mg/kg) of TAT-CBD3 (Supplementary Fig. 9).

As pharmacological block of N-type channels has been linked to anxiety and depression-like behaviors47, we tested if TAT-CDB3 could alter these behaviors. Anxiety reflects a conflict between risk and reward48 and can be evaluated in rodents using the elevated plus maze (EPM) and the Light-Dark Box test (LDBT). These paradigms assess the conflict mice have against hiding in enclosed dark areas (i.e., dark box or closed arm) and their tendency to explore novel environments (i.e., white box or open arm)49, 50. In the EPM test, neither the time spent in the open or closed arm, nor the frequency of entries into the open nor closed arms were altered by any of the 3 doses of TAT-CBD3, compared to the TAT-Scramble group (Fig. 6i, Supplementary Table 1). In the LDBT, the number of transitions between the light and dark box were increased in mice injected with 1 mg/kg TAT-CBD3, compared to TAT-Scramble (Fig. 6j). Overall, this suggests that TAT-CBD3 does not affect anxiety-associated behaviors in these animals with the exception of increasing transitions in the LDBT, suggesting slightly anxiolytic properties.

Since rodents such as mice and rats display immobile postures when placed in inescapable stressful situations51, immobility behavior in the tail suspension test (TST) or forced swim test (FST) is used as a measure of “depression” or “despair-associated” behavior. Furthermore, administering antidepressant treatments prior to testing reduces immobility behavior [see review52]. Therefore, TST and FST are often used to screen novel drugs for depressant or anti-depressant properties. In the TST, neither the time spent immobile, nor the frequency of immobility episodes were altered by any of the 3 doses of TAT-CBD3, compared to TAT-Scramble group (Fig. 6k, Supplementary Table 1). Overall, no dose of the treatment drug altered depression/despair-associated behavior.

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that administration of the TAT-conjugated CBD3 peptide interferes with CaV2.2 trafficking to the presynaptic membrane and that the physiological consequences of TAT-CBD3 peptide treatment include inhibition of stimulus-evoked neuropeptide release from sensory neurons and antinociception in animal models of both acute and chronic pain without altering baseline nociception. Local administration of the TAT-CBD3 peptide prevented nociceptive behaviors in the formalin test and in the capsaicin eye-wipe test. Following the establishment of pain behavior, systemic administration of TAT-CBD3 reversed nociceptive behaviors in a rodent model of antiretroviral toxic neuropathy.

CaV2.2-containing small diameter sensory neurons within the peripheral nervous system53 are responsible for relaying nociceptive signals primarily through their synaptic contacts with spinothalamic tract neurons in laminae I and II30, 54, 55. Calcium influx through CaV2.2 on the A-δ and C fibers triggers release of transmitters such as substance P and glutamate30, 55, 56 and affects the repetitive firing patterns of these fibers30. Thus, pharmacologic block of CaV2.2 not only reduces pre-synaptic neurotransmitter release but may also decrease the excitability of the post-synaptic neurons within lamina I of the spinal cord56. Indeed, CaV2.2 has been implicated in playing a critical role in instigating the increased excitability and neurotransmitter release associated with chronic and neuropathic pain conditions57.

Genetic and pharmacological methods which block CaV2.2 following injury in rodents attenuate nociceptive behavior including inhibition of mechanical allodynia58 and increased thresholds for nociception59. Moreover, expression of CaV2.2 is upregulated in several animal models of neuropathic pain57, 60. Inhibition of CaV2.2 is also one mechanism by which opioid receptors induce analgesia upon activation by morphine61. A pro-nociceptive role for CaV2.2 is further highlighted by the identification of alternative splice variants of CaV2.2 which are expressed on small-diameter nociceptive neurons62 and contribute to thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia63. For these reasons, CaV2.2 has become a prime therapeutic target in the treatment of chronic pain.

CRMP-2 assists in trafficking the CaV2.2 to the plasma membrane to increase calcium current density9, 10, influence vesicle recycling9, 10, and modulate CGRP release from primary sensory neurons10. We reasoned that by uncoupling the interaction between CaV2.2 and CRMP-2 within primary afferent sensory neurons, we would be able to mimic the inhibition of neurotransmitter release observed with siRNA knockdown of CRMP-2. Furthermore, blockade of the interaction and subsequent decreases in excitability and neurotransmitter release would likely result in decreased hypersensitivity in a number of animal pain models.

To block interactions between CRMP-2 and the N-type calcium channel, we designed a peptide, CBD3, which binds to a region within CaV2.2 that is highly conserved between rodents and humans, and contains little or no sequence homology with other proteins. We conjugated the peptide to the HIV-1 TAT domain to overcome the obstacle of poor plasma membrane penetrance of peptides64, 65. Our results show that conjugation of CBD3 to HIV-1 TAT facilitated its passage into cells in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo within minutes.

Pretreatment with the TAT-CBD3 peptide attenuated evoked neurotransmitter release from both hippocampal and sensory neurons, an effect which is likely due to the peptide inhibiting both CaV2.2 trafficking to the plasma membrane and diminished vesicular recycling. We also observed a decrease in capsaicin-evoked blood flow in the dura mater, demonstrating downstream physiological effects of TAT-CBD3 inhibition of peripheral neuropeptide release. Importantly, evidence from electrophysiology and calcium imaging suggests that the action of TAT-CBD3 is mediated predominantly via N-type calcium channels, thus reducing the risk of off-target effects.

To determine the effects of TAT-CBD3 peptide on nociception, we used a variety of animal models of pain which included both the trigeminal and spinal systems and encompassed acute and inflammatory/chronic nociception states. Behavioral outcomes from the capsaicin eye-wipe test37, suggested that the peptide inhibits acute nociception. We also observed peptide inhibition of acute nociception in phase I of the formalin test. Pretreatment with TAT-CBD3 peptide reduced acute nociception by more than 50%, an effect similar to that observed with intrathecal administration of ω-conotoxin, an inhibitor of N-type calcium channels58. The observation that the effects of TAT-CBD3 were antinociceptive in acute studies is consistent with activity-dependent regulation demonstrated for the CRMP-2–CaV2.2 interaction9, suggesting a decrease in presynaptic neuronal excitability.

As significant edema was observed following injection of 2.5% formalin, the second phase of the formalin test is used as a model of inflammation-induced hypersensitivity. Within this model, we were able to demonstrate inhibitory effects of TAT-CBD3 peptide in a manner similar to intrathecal delivery of ω-conotoxin66. We observed a greater effect of TAT-CBD3 in the phase 1 of the formalin test compared to during phase 2, a difference which at first may suggest a more pronounced involvement of Cav2.2 in primary nociception than in the perception of inflammatory pain. However, the observed discrepancy may be due to locally (i.e. into the dorsal surface of the paw) administrated TAT-CBD3 preferentially targeting peripheral release versus synaptic transmission in the dorsal horn. Interestingly, the results from the capsaicin- and formalin-induced nocifensive behaviors and blood flow suggest TAT-CBD3 has an inhibitory effect on the peripheral nerve terminal which, in turn, modulates CGRP release and/or influences neuronal hypersensitivity.

Additionally, our findings also show that TAT-CBD3 peptide suppresses tactile hypersensitivity in an animal model of HIV-treatment-induced peripheral neuropathy, a chronic model of neuropathic pain. This model employs the anti-retroviral treatment 2’,3’dideoxycitidine (ddC) to induce the small fiber dying back neuropathy that is seen in post-treatment AIDS patients40, 41, 67-69. Animals treated with ddC exhibit hyperalgesia and allodynia40, 41, 69. It had been suggested that the neuropathy within the ddC model is a result of decreased calcium buffering, as treatment with calcium buffering agents attenuated the ddC-induced neuropathy to a slight degree40, 41, 69. Interestingly, in this animal model of pain, the peptide is administered systemically after the development of chronic hypersensitivity and is still able to effectively attenuate nociceptive behaviors, suggesting a continued role for the interaction of CRMP-2 and CaV2.2 on neurotransmitter release. Consistent with this hypothesis, others have shown that CaV2.2 mediates an enhanced release of neurotransmitters in the spinal cord important for the maintenance of inflammatory pain66.

Despite the promising potential of pharmacological inhibitors of N-type channels, such as Prialt, in the treatment of intractable or chronic pain conditions, they are overshadowed by a narrow therapeutic window30. Intrathecal delivery of Prialt in animal and clinical studies results in a multitude of deleterious side-effects including impaired learning and memory, motor coordination, and increased anxiety/depression6, 30, 55, 70. At doses more than 50-fold higher than that required to reduce hypersensitivity in vivo, TAT-CBD3 exerted no effect on motor coordination, spatial learning and memory, or anxiety and depression-associated behaviors in these animals. The relative low levels of toxicity observed with systemic delivery of TAT-CBD3 provide promising evidence of its therapeutic potential.

From these findings, we propose that TAT-CBD3 allows suppression of pain hypersensitivity without directly blocking CaV2.2, but rather by inhibiting the binding of a regulator of CaV2.2 function, CRMP-2. Thus, our findings represent a novel approach potentially useful in managing clinical pain.

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NIDCR (DE14318-06 to J.C.F.), NINDS (NS051668 to C.M.H and NS050131 to N.B.), NIEHS (ES017430 to J.H.H.), NINDS (DA026040-03 to F.A.W.), the Indiana State Department of Health – Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Fund (A70-0-079212 to N.B. and A70-9-079138 to R.K.) and the Indiana University Biomedical Committee – Research Support Funds (2286501 to R.K) and the Elwert Award in Medicine to R.K. S.M.W. is a Stark Scholar. We thank Dr. Gerry Oxford (SNRI, Indiana University School of Medicine), members of the Pain and Sensory Group (SNRI, IUSM), Sumeet Kumar Ahuja for assistance with some behavioral experiments, and Carol Kohn for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.B. performed the molecular biology and biochemistry experiments and analyzed the data. D.B.D. carried out the spinal cord slice release and formalin behavior experiments. S.M.W. performed immunocytochemistry and wrote the manuscript. C.B. carried out the laser Doppler blood flowmetry. W.Z. performed DRG patching. Y.W. conducted whole cell electrophysiology on hippocampal neurons. W.S. and X.J. performed electrophysiology on slices. B.S.S. carried out the DRG release assays. T.B. and N.B. performed and analyzed the calcium imaging experiments. M.K. and S.OM. performed the SPR experiments. N.L. performed the rotarod and water maze experiments. J.C.F. performed the nocifensive behavior experiments and helped write the manuscript. N.M.A. and A.H. synthesized the peptide blot. C.M.H. and M.R.V. contributed to editing of the manuscript. J.H.H. analyzed the blood flow data and edited the writing of the manuscript. F.A.W. analyzed the ddC behavior data and contributed to editing the manuscript. R.K. conceived the study, designed and supervised the overall project and wrote the manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;32:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531. 1-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crofford LJ. Adverse effects of chronic opioid therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010;6:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staats PS, et al. Intrathecal ziconotide in the treatment of refractory pain in patients with cancer or AIDS: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:63–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauck RL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of intrathecal ziconotide in adults with severe chronic pain. J. Pain Symptom. Manage. 2006;31:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace MS, et al. Intrathecal ziconotide for severe chronic pain: safety and tolerability results of an open-label, long-term trial. Anesth. Analg. 2008;106:628–37. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181606fad. table. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidtko A, Lotsch J, Freynhagen R, Geisslinger G. Ziconotide for treatment of severe chronic pain. Lancet. 2010;375:1569–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA, Few AP. Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:882–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolphin AC. Calcium channel diversity: multiple roles of calcium channel subunits. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009;19:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brittain JM, et al. An atypical role for collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP-2) in neurotransmitter release via interaction with presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:31375–31390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi XX, et al. Regulation of N-type voltage-gated calcium (CaV2.2) channels and transmitter release by collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP-2) in sensory neurons. J. Cell Sci. 2009;23:4351–4362. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goshima Y, Nakamura F, Strittmatter P, Strittmatter SM. Collapsin-induced growth cone collapse mediated by an intracellular protein related to UNC-33. Nature. 1995;376:509–514. doi: 10.1038/376509a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inagaki N, et al. CRMP-2 induces axons in cultured hippocampal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:781–782. doi: 10.1038/90476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura T, et al. GSK-3beta regulates phosphorylation of CRMP-2 and neuronal polarity. Cell. 2005;120:137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita T, Sobue K. Specification of neuronal polarity regulated by local translation of CRMP2 and Tau via the mTOR-p70S6K pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:27734–27745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arimura N, et al. CRMP-2 directly binds to cytoplasmic dynein and interferes with its activity. J. Neurochem. 2009;111:380–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukata Y, et al. CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote microtubule assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:583–591. doi: 10.1038/ncb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: delivery of a biologically active protein into the mouse. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrade A, Denome S, Jiang YQ, Marangoudakis S, Lipscombe D. Opioid inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels and spinal analgesia couple to alternative splicing. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1249–1256. doi: 10.1038/nn.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzon NM, Foehring RC. Characterization of pharmacologically identified voltage-gated calcium channel currents in acutely isolated rat neocortical neurons. II. Postnatal development. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1443–1451. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Gu XQ, Haddad GG. Calcium influx via L- and N-type calcium channels activates a transient large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ current in mouse neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3639–3648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03639.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomson AM. Facilitation, augmentation and potentiation at central synapses. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto T, Takahara A. Recent updates of N-type calcium channel blockers with therapeutic potential for neuropathic pain and stroke. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:377–395. doi: 10.2174/156802609788317838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodge FA, Jr., Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action a calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J. Physiol. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patapoutian A, Tate S, Woolf CJ. Transient receptor potential channels: targeting pain at the source. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:55–68. doi: 10.1038/nrd2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goadsby PJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists and migraine: is this a new era? Neurology. 2008;70:1300–1301. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000309214.25038.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olesen J, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist BIBN 4096 BS for the acute treatment of migraine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:1104–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao Y, Richter JA, Hurley JH. Release of glutamate and CGRP from trigeminal ganglion neurons: Role of calcium channels and 5-HT1 receptor signaling. Mol. Pain. 2008;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-12. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eikermann-Haerter K, Moskowitz MA. Animal models of migraine headache and aura. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008;21:294–300. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282fc25de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurosawa M, Messlinger K, Pawlak M, Schmidt RF. Increase of meningeal blood flow after electrical stimulation of rat dura mater encephali: mediation by calcitonin gene-related peptide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1397–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snutch TP. Targeting chronic and neuropathic pain: the N-type calcium channel comes of age. NeuroRx. 2005;2:662–670. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubuisson D, Dennis SG. The formalin test: a quantitative study of the analgesic effects of morphine, meperidine, and brain stem stimulation in rats and cats. Pain. 1977;4:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunskaar S, Hole K. The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain. 1987;30:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickenson AH, Sullivan AF. Subcutaneous formalin-induced activity of dorsal horn neurones in the rat: differential response to an intrathecal opiate administered pre or post formalin. Pain. 1987;30:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coderre TJ, Vaccarino AL, Melzack R. Central nervous system plasticity in the tonic pain response to subcutaneous formalin injection. Brain Res. 1990;535:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo A, Vulchanova L, Wang J, Li X, Elde R. Immunocytochemical localization of the vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1): relationship to neuropeptides, the P2X3 purinoceptor and IB4 binding sites. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:946–958. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura A, et al. Morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of the trigeminal ganglion neurons innervating the cornea and upper eyelid of the rat. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2007;34:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farazifard R, Safarpour F, Sheibani V, Javan M. Eye-wiping test: a sensitive animal model for acute trigeminal pain studies. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 2005;16:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szolcsanyi J, Jancso-Gabor A. Sensory effects of capsaicin congeners I. Relationship between chemical structure and pain-producing potency of pungent agents. Arzneimittelforschung. 1975;25:1877–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diogenes A, et al. Prolactin modulates TRPV1 in female rat trigeminal sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:8126–8136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0793-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joseph EK, Chen X, Khasar SG, Levine JD. Novel mechanism of enhanced nociception in a model of AIDS therapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Pain. 2004;107:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhangoo SK, Ripsch MS, Buchanan DJ, Miller RJ, White FA. Increased chemokine signaling in a model of HIV1-associated peripheral neuropathy. Mol. Pain. 2009;5:48. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-48. 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai SR, et al. The kinetics and tissue distribution of protein transduction in mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;27:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamura M, et al. Increased vulnerability of NFH-LacZ transgenic mouse to traumatic brain injury-induced behavioral deficits and cortical damage. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:762–770. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onyszchuk G, He YY, Berman NE, Brooks WM. Detrimental effects of aging on outcome from traumatic brain injury: a behavioral, magnetic resonance imaging, and histological study in mice. J. Neurotrauma. 2008;25:153–171. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D'Hooge R, De Deyn PP. Applications of the Morris water maze in the study of learning and memory. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2001;36:60–90. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gage FH, Chen KS, Buzsaki G, Armstrong D. Experimental approaches to age-related cognitive impairments. Neurobiol. Aging. 1988;9:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rauck RL, Wallace MS, Burton AW, Kapural L, North JM. Intrathecal ziconotide for neuropathic pain: a review. Pain Pract. 2009;9:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowry CA, Johnson PL, Hay-Schmidt A, Mikkelsen J, Shekhar A. Modulation of anxiety circuits by serotonergic systems. Stress. 2005;8:233–246. doi: 10.1080/10253890500492787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bourin M, Hascoet M. The mouse light/dark box test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003;463:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lalonde R, Strazielle C. Relations between open-field, elevated plus-maze, and emergence tests as displayed by C57/BL6J and BALB/c mice. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;171:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varty GB, Cohen-Williams ME, Hunter JC. The antidepressant-like effects of neurokinin NK1 receptor antagonists in a gerbil tail suspension test. Behav. Pharmacol. 2003;14:87–95. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cryan JF, Mombereau C, Vassout A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:571–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westenbroek RE, Hoskins L, Catterall WA. Localization of Ca2+ channel subtypes on rat spinal motor neurons, interneurons, and nerve terminals. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:6319–6330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06319.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerr LM, Filloux F, Olivera BM, Jackson H, Wamsley JK. Autoradiographic localization of calcium channels with [125I]omega-conotoxin in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;146:181–183. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zamponi GW, Lewis RJ, Todorovic SM, Arneric SP, Snutch TP. Role of voltage-gated calcium channels in ascending pain pathways. Brain Res. Rev. 2009;60:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heinke B, Balzer E, Sandkuhler J. Pre- and postsynaptic contributions of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to nociceptive transmission in rat spinal lamina I neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19:103–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.03083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winquist RJ, Pan JQ, Gribkoff VK. Use-dependent blockade of Cav2.2 voltage-gated calcium channels for neuropathic pain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;70:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowersox SS, et al. Selective N-type neuronal voltage-sensitive calcium channel blocker, SNX-111, produces spinal antinociception in rat models of acute, persistent and neuropathic pain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:1243–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saegusa H, et al. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain symptoms in mice lacking the N-type Ca2+ channel. EMBO J. 2001;20:2349–2356. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cizkova D, et al. Localization of N-type Ca2+ channels in the rat spinal cord following chronic constrictive nerve injury. Exp. Brain Res. 2002;147:456–463. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seward E, Hammond C, Henderson G. Mu-opioid-receptor-mediated inhibition of the N-type calcium-channel current. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1991;244:129–135. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD, Lipscombe D. Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron. 2004;41:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altier C, et al. Differential role of N-type calcium channel splice isoforms in pain. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:6363–6373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0307-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwarze SR, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: intracellular delivery of biologically active proteins, compounds and DNA. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2000;21:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yoon JS, et al. Characteristics of HIV-Tat protein transduction domain. J. Microbiol. 2004;42:328–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakanishi O, Ishikawa T, Imamura Y. Modulation of formalin-evoked hyperalgesia by intrathecal N-type Ca channel and protein kinase C inhibitor in the rat. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 1999;19:191–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1006937209676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yarchoan R, et al. Phase I studies of 2',3'-dideoxycytidine in severe human immunodeficiency virus infection as a single agent and alternating with zidovudine (AZT). Lancet. 1988;1:76–81. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dubinsky RM, Yarchoan R, Dalakas M, Broder S. Reversible axonal neuropathy from the treatment of AIDS and related disorders with 2',3'-dideoxycytidine (ddC). Muscle Nerve. 1989;12:856–860. doi: 10.1002/mus.880121012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhangoo SK, et al. CXCR4 chemokine receptor signaling mediates pain hypersensitivity in association with antiretroviral toxic neuropathy. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007;21:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Voltage-sensitive calcium channels in spinal nociceptive processing: blockade of N- and P-type channels inhibits formalin-induced nociception. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:4882–4890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04882.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.