Abstract

The gingiva is often the site of localized growths that are considered to be reactive rather than neoplastic in nature. Many of these lesions are difficult to be identified clinically and can be identified as specific entity only on the basis of typical and consistent histomorphology. Peripheral ossifying fibroma is one such reactive lesion. It has been described with various synonyms and is believed to arise from the periodontal ligament comprising about 9% of all gingival growths. The size of the lesion is usually small, located mainly in the anterior maxilla with a higher predilection for females, and it is more common in the second decade of life. A clinical report of a 12-year-old girl with a large peripheral ossifying fibroma in the posterior maxilla showing significant growth and interference with occlusion is presented.

Keywords: Peripheral ossifying fibroma, fibrous epulis, peripheral cemento ossifying fibroma, calcifying fibroblastic granuloma, gingival growth

Introduction

Peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is a reactive soft tissue growth that is usually seen on the interdental papilla. It may be pedunculated or broad based, usually smooth surfaced and varies from pale pink to cherry red in color. It is believed to comprise about 9% of all gingival growths and to arise from the gingival corium, periosteum, and the periodontal membrane. It has also been reported that it represents a maturation of a pre-existing pyogenic granuloma or a peripheral giant cell granuloma.[1]

Clinical report

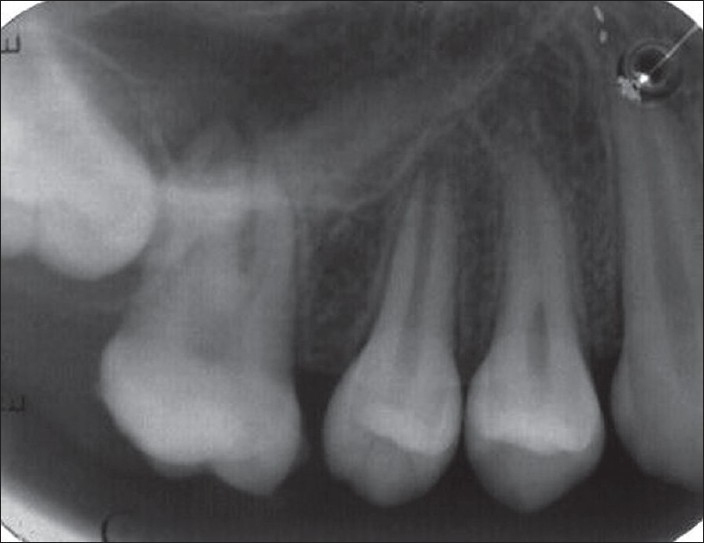

A 12-year-old girl reported with the chief complaint of soft tissue growth in the palate. Intraoral examination revealed a painless pedunculated, cauliflower-like rubbery mass on the palatal aspect of the maxillary left permanent molar extending towards the occlusal surface [Figure 1]. The lesion was abnormally large about 2.5 cm mesiodistally and 1.5 cm buccopalatally and the side of the lesion facing the occlusal surface was focally ulcerated. The maxillary first permanent molar was buccally displaced. History revealed that the lesion started growing on its own since she first noticed it about a month back when it was a small nodule. The lesion was painless and occasionally bled on its own or when traumatized with toothbrush and in its present state was interfering with occlusion. There was no significant medical and familial history. Radiograph revealed only soft tissue shadow and space between maxillary second premolar and first molar [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Soft tissue growth extending toward the occlusal surface

Figure 2.

IOPA showing the soft tissue shadow and space between premolar and molar

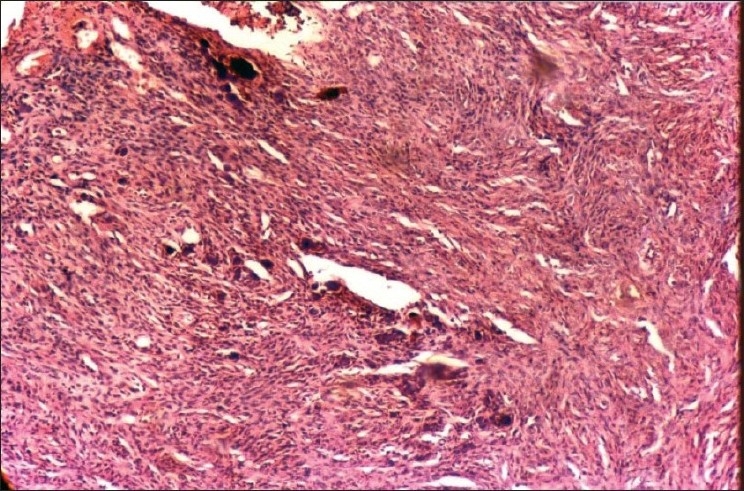

After routine blood examinations, excisional biopsy of the growth was done [Figure 3] under antibiotic coverage and thorough curettage of the adjacent periodontal ligament, and periosteum was carried out to prevent recurrence. Histomorphological examination revealed evidence of calcifications in the hypercellular fibroblastic stroma [Figure 4] confirming the lesion as POF. The follow-up of the case showed normal healing of the area [Figure 5].

Figure 3.

Excised tissue

Figure 4.

Slide showing calcifications in fibroblastic stroma

Figure 5.

Normal healing of the lesion after excision

Discussion

POF has also been described by various synonyms such as peripheral cemento ossifying fibroma, peripheral odontogenic fibroma (PODF) with cementogenesis, peripheral fibroma with osteogenesis, peripheral fibroma with calcification, fibrous epulis, calcifying fibroblastic granuloma, etc.[1,2] Almost 60% of the lesions occur in the maxilla and mostly occur anterior to molars. The lesion is most common in the second decade of life affecting mainly females.[3] Dental calculus, plaque, microorganisms, dental appliances, and restorations are considered to be the irritants triggering the lesion.[4] The lesion though usually smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter can reach a much larger size and can cause separation of the adjacent teeth, resorption of the alveolar crest, destruction of the bony structure and cosmetic deformity.[5]

The term POF should not be confused with PODF, which is the rare peripheral counterpart of central odontogenic fibroma. In North America, it is still synonymously used by many for POF as the lesion is thought by them to be derived from the periodontal ligament and hence to be odontogenic. The evidence for its odontogenic origin is circumstantial, being based partly on the demonstration of oxytalan fibers within its calcified structures and its exclusive occurrence on gingiva. However, oxytalan fibers have also been reported in the sites other than the periodontal ligament.[4] A POF is more common in females and in the anterior maxilla, but PODF has a predilection for males and the posterior mandible.[6] Even an unusual occurrence of a POF associated with dental pulp has been reported.[7]

The POF and ossifying fibroma (OF) are the lesions that exhibit similar histomorphologic features and both originate from periodontal ligament cells. But a POF is a reactive lesion where as an OF is a benign neoplastic lesion included in the group of benign fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws and both POF and OF show different proliferative activities.[8] The ulcerated lesions are more likely to be painful but in this case it was not painful. Gingival lesions that imitate POF are peripheral giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, fibroma, calcifying epithelial odontogenic cyst, calcifying odontogenic cyst, etc.[9]

Radiographically radiopaque foci within the soft tissue tumor mass are observed if the calcified element is significant, but in this case no radiopaque foci were seen but only shadow of the lesion was seen probably because the lesion was of short duration of time.

Histologically, POF can exhibit either ulcerated or intact stratified squamous epithelium. In a typical ulcerated lesion, three zones could be identified:

Zone I: The superficial ulcerated zone covered with the fibrinous exudate and enmeshed with polymorphonuclear neutrophils and debris.

Zone II: The zone beneath the surface epithelium composed almost exclusively of proliferating fibroblasts with diffuse infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells mostly lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Zone III: More collagenized connective tissue with less vascularity and high cellularity; osteogenesis consisting of osteoid and bone formation is a prominent feature, which can even reach the ulcerated surface in some cases.

The calcified material can generally take one or more of the following four forms: (a) mature lamellated trabecular bone; (b) immature, highly cellular bone; (c) circumscribed amorphous, almost acellular, eosinophilic, or basophilic bodies, and (4) minute microscopic granular foci of calcification.[1]

The nonulcerated lesions are typically identical to the ulcerated type except for the presence of surface epithelium. Cementum-like material is found in less than one-fifth of the lesions and dystrophic calcifications are more prevalent in ulcerated lesions.[3]

Treatment requires proper surgical intervention that ensures deep excision of the lesion including periosteum and affected periodontal ligament. Thorough root scaling of adjacent teeth and/or removal of other sources of irritants should be accomplished. In children, reactive gingival lesions can exhibit an exuberant growth rate and reach significant size in a relatively short period of time. In addition, the POF can cause erosion of bone, can displace teeth, and can interfere or delay eruption of teeth. Early recognition and definitive surgical intervention result in less risk of tooth and bone loss.[6] The recurrence rate varies from 7 to 20% according to different authors.[4]

It is suggested that there is no absolute histological distinction between bone and cementum, and as the so-called cementum-like globules of calcification are seen in fibro-osseous lesions in all membrane bones, it is unrealistic to separate the ossifying and cementifying lesions and it is speculated that the fibro-osseous lesions might represent stages in the evolution of a single disease process passing through the stages of fibrous dysplasia to ossifying fibroma to cementoid lesions.[10]

In conclusion, clinically it is difficult to differentiate between most of the reactive gingival lesions particularly in the initial stages. Regardless of the surgical technique employed, it is important to eliminate the etiological factors and the tissue has to be histologically examined for confirmation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bhaskar NS, Jacoway JR. Peripheral Fibroma and Peripheral Fibroma with Calcification: Report of 376 Cases. JADA. 1966;73:1312–20. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1966.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walters JD, Will JK, Hatfield RD, Cacchillo DA, Raabe DA. Excision and Repair of the Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma: A Report of 3 Cases. J Periodontal. 2001;72:939–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchner A, Hansen LS. The Histomorphologic Spectrum of Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452–61. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner DG. The peripheral odontogenic fibroma: An attempt at clarification. Oral Surg. 1982;54:40–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(82)90415-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poon CK, Kwan PC, Chao SY. Giant peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:695–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenney JN, Kaugars GE, Abbey LM. Comparision between the peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheral odontogenic fibroma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:378–82. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baumgartner JC, Stanley HR, Salomone JL. Zebra Hunt. J Endod. 1991;17:181–5. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)82014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesquita RA, Orsini SC, Sousa M, de Araújo NS. Proliferative activity in peripheral ossifying fibroma and ossifying fibroma. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:64–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuisia ZE, Brannon RB. Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma-A Clinical Evaluation of 134 Pediatric Cases. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:245–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langdon JD, Rapidis AD, Patel MF. Ossifying Fibroma-One Disease or Six? An Analysis of 39 Fibro-Osseous Lesions of the Jaws. Br J Oral Surg. 1976;14:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(76)90087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]