Abstract

Background

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is a difficult disease to treat with low response rates with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, has demonstrated objective responses in BAC patients in early phase clinical trials. We conducted a phase II study of bortezomib inpatients with advanced stage BAC.

Methods

Patients with advanced BAC, adenocarcinoma with BAC features or BAC with adenocarcinoma features and less than two prior regimens were eligible. Prior epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy was allowed. Bortezomib was administered intravenously at 1.6 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of every 21 days cycle until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary endpoint was response rate. The Simon two-stage design was utilized.

Results

Forty-two patients were enrolled and the study was halted early for slow accrual. Patient characteristics were: female 55%, median age 68 years, and ECOG performance status of 0 and 1 in 31 and 11 patients respectively. Twenty-six(62%)patients had received prior therapy with an EGFR inhibitor. A median of 4 cycles of therapy were administered. Objective responses were noted in 5% while 57% had disease stabilization. The median progression-free survival and overall survival were 5.5 months and 13.6 months respectively. Grade 3 diarrhea and fatigue were noted in 3 and 5 patients respectively.

Conclusions

Bortezomib is tolerated well and is associated with modest anti-cancer activity in advanced BAC, including inpatients that progressed on EGFR inhibitor therapy.

Keywords: bortezomib, proteasome inhibition, BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, NSCLC

Introduction

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) is a sub-type of adenocarcinoma of the lung that is characterized by unique biology and clinical behavior. According to the World Health Organization classification (1999), it is defined as ‘an adenocarcinoma with a pure bronchioloalveolar growth pattern without evidence of stromal, vascular or pleural invasion’1. BAC accounts for approximately 3–4% of all lung cancers2. In addition, 10–15% of patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung have BAC features when evaluated under microscopy. In recent years, the incidence of BAC appears to be on the rise3. Compared to other subtypes of NSCLC, a greater proportion of women and never-smokers present with BAC4.

Despite the favorable prognosis for patients with BAC compared to invasive adenocarcinoma, responsiveness to standard cytotoxic chemotherapy has been poor5. Two phase II studies of paclitaxel as therapy for advanced BAC reported low response rates and modest survival6,7. Recently, the use of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), gefitinib and erlotinib have resulted in a somewhat higher response rate and improvement in survival for patients with advanced BAC. In a phase II study by the Southwest Oncology Group, gefitinib was associated with a response rate of 17% and a median survival of 13 months in patients with advanced BAC, better than historical results for chemotherapy alone. Similar results were noted in another phase II study with gefitinib for patients with advanced BAC8. The response rate in that trial was 13% and the median survival was 13.2 months. Erlotinib has also demonstrated modest anti-cancer effects in a phase II study for patients with advanced BAC9. In particular, patients with an activating EGFR mutation had a very high response rate of 83% with erlotinib. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFR, was evaluated as monotherapy for BAC in a phase II study by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG 1504)10. Despite a low response rate, the median time-to-progression and overall survival were approximately 4 months and 13 months respectively. Although these studies have demonstrated a role for EGFR inhibitors for the treatment of BAC, the benefit in wild type tumors is modest at best. There is a clear need to develop other agents for the treatment of this disease, given the poor prognosis for advanced BAC.

Bortezomib is a small molecule proteasome inhibitor that has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma and refractory or relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. Clinical data suggests that it is active in the treatment of NSCLC with a single agent response rate of approximately 10%11. Bortezomib has also demonstrated similar modest efficacy when given in combination with various chemotherapeutic agents in patients with advanced stage NSCLC11–13. Furthermore, objective responses to bortezomib in BAC patients have been anecdotally reported in case reports as well as in the initial phase I trials of this agent14,15,16. Based on these observations, we conducted a phase II study to formally evaluate the efficacy of bortezomib in patients with advanced BAC.

Though the approved schedule of bortezomib involves intravenous administration on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 every 3 weeks, we pursued a weekly regimen for this study, to minimize patient inconvenience and toxicity. The weekly schedule has been studied by Papandreou et al and was associated with promising efficacy and good tolerability in patients with advanced prostate cancer17. With a dose of 1.6 mg/m2, the desired biological effects were noted in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and in tumor biopsies. The weekly schedule has also been found to have comparable efficacy and a favorable safety profile in patients with multiple myeloma 18.

Patients and methods

The primary objective of this phase II study was to determine the objective response rate with bortezomib in patients with advanced BAC. Secondary objectives included determination of overall survival, progression-free survival, toxicity and the safety of bortezomib administered on a weekly schedule.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with histologically confirmed stage IIIB/IV BAC or adenocarcinoma with BAC features were eligible. Other salient inclusion factors were presence of measurable disease, age > 18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, 1 or 2, and life expectancy greater than 3 months. Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1500/μL, platelet count ≥ 100,000/μL, total serum bilirubin within institutional normal limits, and serum hepatic transaminases level ≤ 2.5 times institutional upper limit of normal were required for eligibility. For patients with an elevated serum creatinine level, the creatinine clearance had to be ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients could have received one prior chemotherapy regimen. Prior treatment with an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor was allowed. A minimum of three-week interval from prior chemotherapy and a 2-week interval from prior EGFR inhibitor therapy were required for study initiation. Patients with unstable or untreated brain metastasis, prior therapy with bortezomib, grade 2 or greater neuropathy, serious uncontrolled co-morbid illness and history of another advanced cancer were excluded. Pregnant or lactating women were not included. All patients were required to sign a written informed consent. This open-label, multi-center study included participation from academic institutions in four NCI-sponsored phase II consortia and their community partners. The clinical trial protocol was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Treatment and assessment

Bortezomib was administered intravenously over 3 to 5 seconds at a dose of 1.6 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle. Treatment was continued until disease progression, development of unacceptable toxicity or patient decision to withdraw from the study. Patients were required to have an ANC of > 1500/μL and platelet count of 100,000/μL before initiation of each new cycle of treatment. On day 8, the ANC and platelet counts had to be above 1000/μL and 75,000/μL, in which case the patient was given the same dose of bortezomib as on day 1. If the counts were either 500–999/μL and/or 50,000–75,000/μL respectively, the dose was reduced by 0.3 mg/m2. If the ANC and/or platelet counts were less than 500/L and 50,000/L, day 8 therapy was held and the patient was re-evaluated the following week for drug administration. If the dose of bortezomib was reduced on day 8 for two consecutive cycles, then the day 1 dose was also reduced for all subsequent cycles by 0.3 mg/m2. The dose of bortezomib was also reduced for grade 1 peripheral neuropathy with pain or grade 2 by 0.3 mg/m2 and held for grade 3 until resolution to grade 1 or less. Bortezomib was to be discontinued permanently if patient developed grade 4 neuropathy. For all other drug-related grade 3 or 4 toxicities, bortezomib was held until resolution to grade 1 or less and subsequently restarted with a dose reduction. All appropriate supportive care measures were allowed in the event of non-hematological toxicities. A maximum of two dose reductions were allowed per patient.

Study evaluations

Patients underwent a physical examination, assessment of height, weight, vital signs and performance status at baseline and at the initiation of each new cycle of therapy. Serum chemistry studies and complete blood count (CBC) with differential were performed at baseline and before each cycle. CBC with differential count was also evaluated once a week throughout the study. CT scans were done at baseline and every 2 cycles of therapy to assess response. Toxicity was graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria version 3.0. Tumor responses were assessed by RECIST criteria19.

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint of the study was to determine the objective response rate with bortezomib in patients with advanced BAC. A response rate of 20% was considered to be of interest, and a response rate of less than 5% would result in accepting the null hypothesis. The Simon’s optimal two-stage design was utilized with 12 patients enrolled to the first stage. One or more responses were required for the study to proceed to full accrual. It was originally designed to include a cohort of patients with prior EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and another cohort of EGFR inhibitor naïve patients. This required a total sample size of 74 patients. Since accrual was slower than anticipated, it was determined that a sample size of 37 patients would provide a 90% probability of recommending against further development if the response rate was 5% or less and a 54% of chance of stopping early. The trial closed after accruing a total of 42 patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty-two patients were enrolled to the study between June 2005 and June 2009. The median age was 68 years and approximately 50% of the patients were women. All patients had an ECOG performance status of either 0 or 1 (Table 1). The majority of the patients had adenocarcinoma with BAC features or BAC with adenocarcinoma features. Twenty-six patients had received prior treatment with an EGFR inhibitor. Of twenty-two patients for whom the smoking history was available, 8 were never-smokers. Fourteen patients received prior therapy with platinum-based regimens, while the others received single agent chemotherapy or non-platinum combinations. Among patients who received an EGFR inhibitor, 7, 16 and 3 had been treated with gefitinib, erlotinib and cetuximab respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 42 |

|

| |

| Female | 23 (55%) |

|

| |

| Median age | 68 (54–75) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 37 (88%) |

| African American | 2 (5%) |

| Asian | 3 (7%) |

|

| |

| Performance status (ECOG) | |

| 0 | 31 (74%) |

| 1 | 11 (26%) |

|

| |

| Histology | |

| BAC, mucinous | 1 (3%) |

| BAC, non-mucinous | 5 (12%) |

| BAC with adenocarcinoma features | 19 (45%) |

| Adenocarcinoma with BAC | 17 (40%) |

|

| |

| Smoking history | |

| Never-smoker | 8 (19%) |

| Former smoker | 12 (29%) |

| Current smoker | 2 (5%) |

| Not available | 20 (47%) |

|

| |

| Prior therapy | |

| EGFR inhibitor | 26 (62%) |

| Chemotherapy | |

Treatment delivery and toxicity

The median number of cycles of bortezomib was four. Patients who had not received prior EGFR inhibitor therapy received a higher number of cycles of bortezomib (4.5 vs. 2.5, P = 0.12). Treatment was tolerated well and there were no treatment-related deaths. Two patients experienced treatment-related grade 4 toxicity of elevated serum bilirubin and seizures respectively (Table 2). Grade 3 diarrhea, fatigue and pain were noted in 3, 5 and 2 patients respectively. Twenty eight patients discontinued therapy due to disease progression. Only five patients discontinued treatment due to treatment-related toxicity.

Table 2.

Grade 3/4 Toxicity*

| CTC AE Terminology | Grade 3 (N) | Grade 4 (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Dehydration | 1 | |

| Diarrhea | 3 | |

| Dyspnea | 1 | |

| Fatigue | 5 | |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 1 | |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | |

| Hypernatremia | 1 | |

| Hyponatremia | 1 | |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | |

| Muscle weakness | 1 | |

| Myalgia | 1 | |

| Nausea | 1 | |

| Neuropathy | 1 | |

| Neutropenia | 1 | |

| Pain | 2 | |

| Seizure | 1 | 1 |

| Syncope | 1 |

represents worst grade of toxicity that is attributable to therapy by number of patients

Efficacy

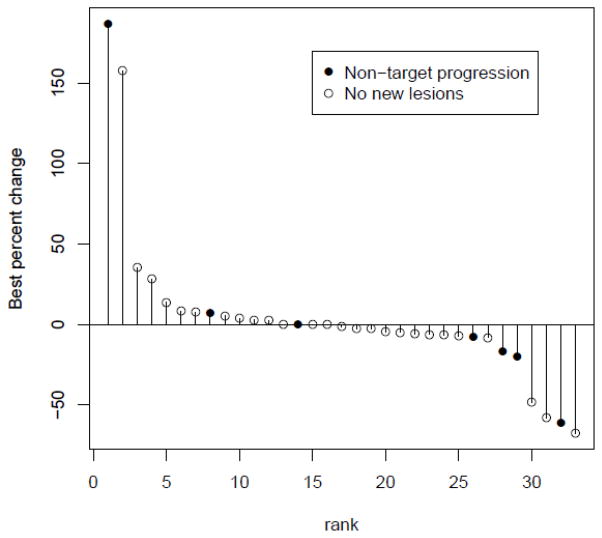

A pre-planned interim analysis was conducted after 12 patients were enrolled in each in the two cohorts. One partial response was noted in each cohort. This met the criteria to proceed to full accrual. Of the 42 patients who were enrolled in total, two patients had a confirmed partial response. Two additional responses were noted, but were not subsequently confirmed. A female patient that had progressed on prior EGFR inhibitor therapy experienced a partial response and received 22 cycles of therapy. Her disease remained under control for an additional 96 weeks. The second response occurred in a male who received a total of 29 cycles of therapy. Another patient with a partial response to bortezomib chose to switch to erlotinib therapy after only 3 cycles and was on follow up for over 100 weeks without progression. Disease stabilization was noted in 24 patients (57%). Among patients with prior EGFR inhibitor therapy, 1 had a partial response and 12 had stable disease. Sequential tumor measurements from 33 out of 42 patients are illustrated in figure 1 as a waterfall plot. The median PFS and overall survival were 5.5 months and 13.6 months respectively. In the cohort of patients with prior EGFR inhibitor therapy, the median PFS and overall survival were 2.3 months and 21 months respectively. For patients without prior therapy with an EGFR inhibitor, the median PFS and OS were 6.5 months and 13.6 months respectively.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot of anti-tumor activity

Discussion

BAC often presents as ground-glass opacities on radiographic studies and is treated with surgical resection in patients with localized disease. However, in many patients it presents as multi-focal disease or metastatic disease that is not amenable to local therapy. In such instances, systemic therapy is the mainstay of treatment. EGFR TKIs have demonstrated modest activity in the treatment of BAC. In addition, targeting the external domain of the EGFR with a monoclonal antibody also appears to be associated with modest efficacy in patients with advanced BAC. Regardless of the extent of initial sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors, majority of the patients experience disease progression in less than 5 months and require subsequent therapies. The reasons behind the sensitivity of BAC to EGFR inhibitors could be linked to the higher prevalence of EGFR mutation in this patient population.

The present study documented modest anti-cancer activity with bortezomib in patients with advanced stage BAC or adenocarcinoma with BAC features. Interestingly, anti-cancer activity appeared to be similar between patients that received prior EGFR inhibitor and those that did not. Given the fact that patients with BAC do not appear to derive robust benefits with chemotherapy, bortezomib might be considered a reasonable alternative therapeutic option. However, our study is limited by a small sample size and the lack of a comparator “control” arm. It must be noted that a standard “control” treatment arm has not yet been defined for BAC at the time of study design. We also relied on institutional pathologic evaluations with regards to the BAC diagnosis as we did not perform a central pathology review. Only one of the three studies reported to date with EGFR inhibitors for the treatment of BAC had central verification of pathology to confirm the diagnosis. The relatively long survival duration observed in some sub-groups of patients despite a short PFS, also illustrates the distinctly different disease course among patients with BAC. This longer survival is more likely to represent indolent disease biology rather than a drug-effect.

Despite the increasing incidence of BAC and the recognition of its limited responsiveness to chemotherapy, patients with BAC continue to be treated along similar lines as other histological subtypes of NSCLC. In many instances, BAC is under-recognized possibly due to the lack of adequate tumor sample in the original diagnostic biopsy. In recent years, histology has become an important factor for selection of both chemotherapy and targeted therapy for patients with NSCLC20. This has necessitated obtaining core biopsies instead of fine needle aspiration biopsies and has also placed a stronger emphasis on identifying the histological sub-type. This could help with the identification of patients with BAC and thus improve accrual of the patients to studies specific to BAC. The new pathological classification of adenocarcinoma could also help in the identification of patients with BAC features21.

Bortezomib has been studied extensively in patients with advanced NSCLC as either monotherapy, and in combination with chemotherapy in the first and second line settings. Though it is active as a single agent with response rate of approximately 10%, there has been no evidence of robust synergy with chemotherapy in these studies. As a result, this agent has not been developed further in NSCLC. However, a number of newer proteasome inhibitors with improved pharmacokinetic properties and favorable toxicity profile are under clinical and pre-clinical development22. The results of our study suggest that BAC could be an important area for study for these newer agents.

In addition, pre-clinical studies have documented enhanced anti-cancer effects when a proteasome inhibitor was combined with EGFR inhibitors in H358 cells, a bronchioloalveolar cell line23. A randomized phase II study conducted in an unselected group of patients with advanced NSCLC with the combination of bortezomib and erlotinib failed to demonstrate robust efficacy24. Only one of the 57 patients enrolled to this study had pure BAC histology. Therefore, evaluation of the combination of erlotinib and bortezomib in patients with advanced BAC might be a potential avenue to build upon the findings of our study.

In conclusion, given the lack of proven therapies for BAC, the modest efficacy data from our study support the use of bortezomib as a potential therapeutic option, particularly after progression with an EGFR inhibitor. The identification of specific pathways that play a dominant oncogenic role in patients with BAC will help guide the development of specific, individualized treatment options.

Table 3.

Efficacy

| Efficacy parameter | No. of patients/(%) |

|---|---|

| Partial response | 2 (5%) |

| Stable disease | 24 (57%) |

| Disease control rate (PR +SD) | 63% |

| Progression | 15 (36%) |

| Non-evaluable | 1 (2%) |

|

| |

| Median progression free survival | 5.5 months 95% CI: 2.1–6.4 |

|

| |

| Median survival | 13.6 months 95% CI: 49.7-NR* |

NR-not reached

Acknowledgments

Supported by NCI NO1-CM-62209 (California Cancer Consortium), NO1-CM-62201 (University of Chicago Consortium), NO1-CM-62208 (Southeast Phase 2 Consortium)& NO1-CM-62207Ohio State University

Footnotes

Preliminary findings were presented at the 12th World Lung Cancer Conference in Seoul, Korea in September 2007.

References

- 1.Travis WD, Garg K, Franklin WA, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma: the clinical importance and research relevance of the 2004 World Health Organization pathologic criteria. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:S13–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read WL, Page NC, Tierney RM, et al. The epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma over the past two decades: analysis of the SEER database. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsky SH, Cameron R, Osann KE, et al. Rising incidence of bronchioloalveolar lung carcinoma and its unique clinicopathologic features. Cancer. 1994;73:1163–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940215)73:4<1163::aid-cncr2820730407>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breathnach OS, Ishibe N, Williams J, et al. Clinical features of patients with stage IIIB and IV bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1999;86:1165–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1165::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller VA, Hirsch FR, Johnson DH. Systemic therapy of advanced bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3288–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Smit E, Bosquee L, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in advanced bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (EORTC trial 08956) Lung Cancer. 2005;50:91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West HL, Crowley JJ, Vance RB, et al. Advanced bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a phase II trial of paclitaxel by 96-hour infusion (SWOG 9714): a Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1076–80. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cadranel J, Quoix E, Baudrin L, et al. IFCT-0401 Trial: a phase II study of gefitinib administered as first-line treatment in advanced adenocarcinoma with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1126–35. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181abeb5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1472–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalingam SS, Lee JW, Belani CP, et al. Cetuximab for the Treatment of Advanced Bronchioloalveolar Carcinoma (BAC): An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Phase II Study (ECOG 1504) J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fanucchi MP, Fossella FV, Belt R, et al. Randomized phase II study of bortezomib alone and bortezomib in combination with docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5025–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scagliotti GV, Germonpre P, Bosquee L, et al. A randomized phase II study of bortezomib and pemetrexed, in combination or alone, in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;68:420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies AM, Chansky K, Lara PN, Jr, et al. Bortezomib plus gemcitabine/carboplatin as first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II Southwest Oncology Group Study (S0339) J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:87–92. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181915052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aghajanian C, Soignet S, Dizon DS, et al. A phase I trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor PS341 in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2505–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson JP, Nho CW, Johnson SW, et al. Effects of bortezomib (PS-341) on NF-?B activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of advanced non-small lung cancer (NSCLC) patients: A phase II/pharmacodynamic trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;23:649. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subramanian J, Pillot G, Narra V, et al. Response to bortezomib (velcade) in a case of advanced bronchiolo-alveolar carcinoma (BAC). A case report. Lung Cancer. 2006;51:257–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papandreou CN, Daliani DD, Nix D, et al. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors with observations in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2108–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bringhen S, Larocca A, Rossi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of once weekly bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3543–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dick LR, Fleming PE. Building on bortezomib: second-generation proteasome inhibitors as anti-cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piperdi B, Ling YH, Perez-Soler R. Schedule-dependent interaction between the proteosome inhibitor bortezomib and the EGFR-TK inhibitor erlotinib in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:715–21. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3180f60bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch TJ, Fenton D, Hirsh V, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of erlotinib alone and in combination with bortezomib in previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1002–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181aba89f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]