Abstract

One of the most distressing aspects of dentistry for pediatric patients is the fear and anxiety caused by the dental environment, particularly the dental injection. The application and induction of local anesthetics has always been a difficult task, and this demands an alternative method that is convenient and effective. Electronic dental anesthesia, based on the principal of transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), promises to be a viable mode of pain control during various pediatric clinical procedures. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of TENS and to compare its efficacy with 2% lignocaine during various minor pediatric dental procedures. Pain, comfort and effectiveness of both the anesthetics were evaluated using various scales and no significant difference was observed between 2% lignocaine and TENS in the various pain scales, while TENS was perceived to be significantly effective in comfort and efficacy as judged by the operator and quite comfortable as judged by the patient himself/herself.

Keywords: 2% lignocaine, comfort and efficacy, electronic dental anesthesia/TENS, pain scales

Introduction

In pedodontic practice, local anesthesia is required in day to day pediatric dental procedures like extractions, pulpotomies, root canal treatment, drainage of abscess, etc. The only way available to us is the parental route with the use of needle prick. The objective fears of a child during administration of local anesthesia range from sight of the needle to the pain associated with needle insertion, which increases the anxiety of the patient.[1]

Although techniques like general anesthesia and conscious sedation are being approached today, they always carry the risk of morbidity and, also, mortality. Also, general anesthesia is not very cost-effective for minor dental procedures except when the child is below the age of reason or is physically/mentally handicapped.

Electronic dental anesthesia/transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) is a technique that provides us a promising way to produce dental anesthesia by using a mild amount of electric current and is based on the much-established Gateway Theory of pain control given by Malzack and Wall in 1965.[2] TENS is commonly used in many disciplines of medical and paramedical fields. Although the use of TENS in dentistry was first described in the year 1967 by Shane and Kessler, still, there is scarcity of literature on the uses of TENS as an anesthetic apparatus [Figure 1].[3]

Figure 1.

Electronic dental anesthesia/transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and its application during various minor dental procedures

Hence, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of TENS and to compare its efficacy with 2% lignocaine in reducing the pain during various minor pediatric dental procedures.

Materials and Methods

Patients visiting the outpatient department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry with the chief complaint of minor dental ailments requiring use of local anesthesia for the treatment were selected.

A total of 180 patients were selected and were then randomly divided into two equal groups of 90 patients each. Each group was further divided into three subgroups of 30 patients requiring endodontic procedures such as pulpotomy and pulpectomy, cavity preparation where caries extended till the dentinoenamel junction or more and extraction of retained, mobile and grossly carious deciduous teeth where half or more root resorption was seen. Materials used for the study were a transcutaneous elective nerve stimulator and 2% lignocaine solution with adrenaline.

Children between the ages of 5 and 14 years were selected, having ASA Grade 1 status and without any allergic history to local anesthesia.

The required procedures were carried out after taking the written consent from the parents, and each patient was evaluated using the following scales for pain, comfort and effectiveness:

Visual analogue scale for pain[4]

In this, the child was asked to rate the discomfort on a 100-mm VAS, with a smiling child at one end and a tearful child at the other. The distance along the scale from the smiling child was taken as the pain score. In addition, the child was asked which side was least painful.

Verbal pain scale for pain[5]

Score

0 – No pain

1 – Mild pain (pain that is recognizable but not discomfort)

2 – Moderate pain (pain that is discomforting but bearable)

3 – Severe pain (pain that causes considerable discomfort and is difficult to bear)

4 – Very severe/unbearable pain

Lickert scale for comfort and effectiveness of anesthesia

Score

1 – Most uncomfortable/most ineffective

2 – Moderately uncomfortable/ineffective

3 – Minor discomfort/slightly effective

4 – Moderately comfortable/effective

5 – Very comfortable/very effective

Observations and Results

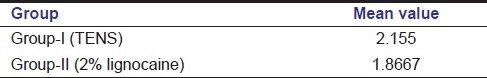

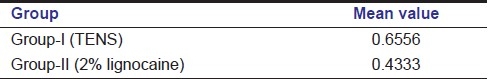

In VAS, the mean values for pain indicate that minimum pain was felt with 2% lignocaine, which was closely followed by TENS [Table 1]. In VPS, patients experienced minimum pain with 2% lignocaine, but the pain was comparable with the TENS group [Table 2].

Table 1.

Mean values for pain with transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and 2% lignocaine in relation to visual analogue scale

Table 2.

Mean values for pain with transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and 2% lignocaine in relation to verbal pain scale

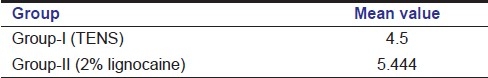

In comfort and efficacy scale, Lickerts’ scale, 2% lignocaine was most comfortable during various procedures, but was closely followed by TENS [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean values for comfort and efficacy with transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation and 2% lignocaine in relation to Lickert's scale

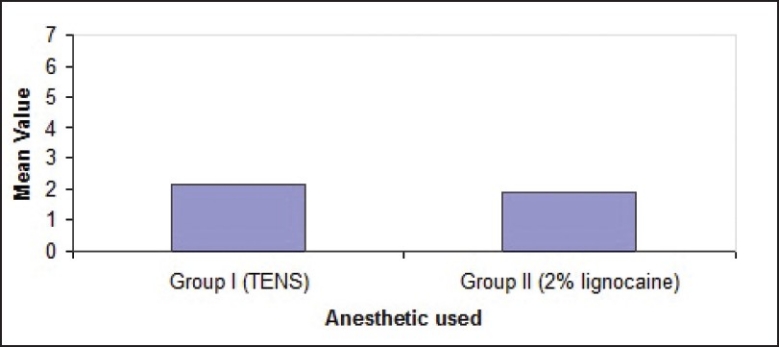

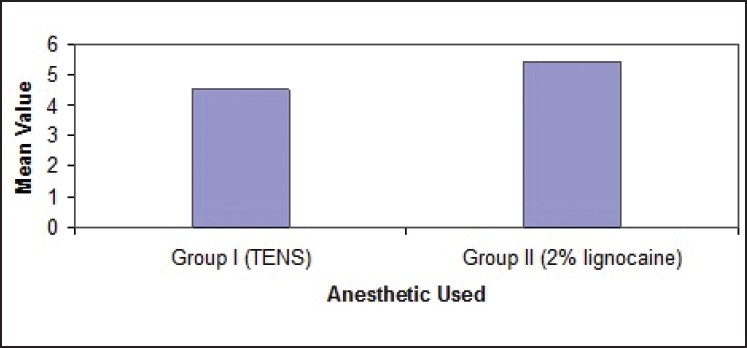

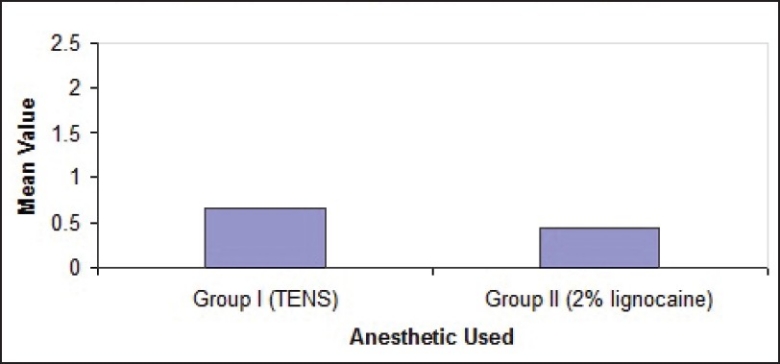

ANOVA values using TENS and 2% lignocaine showed no significant difference (P > 0.05) when VAS, VPS and Lickert's scale were used during various dental procedures [Figures 2–4].

Figure 2.

Mean value for pain comparing the two anesthetics in relation to the visual analogue scale

Figure 4.

Mean value of comfort and efficacy in comparing the two anesthetics in relation to Lickert's scale

Figure 3.

Mean value for pain comparing the two anesthetics in relation to the verbal pain scale

Discussion

In older days, surgical centers were described as the beds of death because of the pain associated with surgical procedures as there were no anesthetic agents available. Actually, the pain is a complex experience that includes not only the sensations evoked by tissue damaging or noxious stimuli but also the reactions or response to each stimuli.

General anesthesia was introduced by William T.G. Morton, a dentist of Boston, on October 16, 1864.[6] But, this technique is cumbersome, time consuming and always carry the risk of morbidity and even mortality and is not suitable for minor dental procedures. This led to the introduction of local anesthesia, which was first demonstrated by Carl Koller of Vienna in 1884 [Figure 1].[7]

Today, local anesthetics are the most commonly employed drugs in dentistry and are probably the most important ones. In pedodontic practice also, local anesthesia is required in day to day dental procedures. The objective fear of a child during administration of local anesthesia is associated with the use of needle prick range from sight of the needle to the pain associated with needle insertion. Also, traditional local anesthesia obtained by dental injection has several drawbacks, including anxiety, psychological factors, local and systemic toxic reactions and paresthesia caused by laceration of regional nerve fibers.[8] Therefore, clinicians employ many techniques to reduce pain and fear associated with dental injections, which mainly includes psychological measures, nitrous oxide, hypnosis and many more.

Psychological measures like modeling, desensitization etc. are simply not enough to overcome the anxiety of an extremely fearful child because of the lack of knowledge and training to apply these techniques, and every method might not be successful for every child. These techniques also involve a significant amount of time during which the patient's dental condition may deteriorate.[6]

Hence, to overcome the drawbacks of local anesthesia, an alternative mode of pain management, which is particularly appealing, is available to us in the form of TENS or electronic dental anesthesia. TENS is one such technique that provides us with an easy way to produce dental anesthesia, and is non-invasive, safe and generally well excepted by the patient.[9]

The objective of TENS is to achieve the deepest level of anesthesia possible by using electric current. The use of electric current as a therapeutic modality in medicine is not new. The ancient Egyptians were the first to apply electric current therapeutically using electric eels in the treatment of headaches and gout.[10] But, the earliest reference to the dental application of TENS appeared in the late 1970s. The fundamental of electronic anesthesia/TENS is the Gateway Control Theory of pain proposed by Malzack and Wall in 1965, which states that the sensation of pain is a complex sum of activity in both nociceptive and non-nociceptive afferent nerve fibers.[11] TENS may operate via a peripheral blocking mechanism of pain impulses. In addition, TENS may also function in part by exciting pathways to the brain that ultimately lead to the activation of endogenous analgesic systems involving opiate-like peptides, such as enkephalin and endorphins.[12]

Hence, the aim of the present study was to comparatively evaluate the effectiveness of TENS with 2% lignocaine solution during various minor dental procedures in pediatric dentistry. The application of TENS was done as advocated by St. Paul MN.[13]

The effectiveness of the anesthetic was recorded using VAS, VPS and Lickert's scale. It was seen that both the anesthetic agents used in the study were found to be effective in reducing pain and anxiety, although to different degrees. Local injectable anesthesia showed the maximum reduction in pain, which was closely followed by TENS. A study conducted by Quarnstorm Fred also concluded that good success was seen for all pediatric procedures including extraction when TENS was used.[10] Bishop TS also reported a 92.8% success with TENS during restorative procedures.[14] Segura et al. also reported minimum pain with TENS in the 7–12 years age group during restorative procedures.[15] Success during endodontic procedures with TENS was also reported by Clark et al.[16]

On the basis of Lickert's scale, the efficacy of TENS was perceived to be significantly effective as judged by the operator and quite comfortable as judged by the patient himself/herself. Yap et al. said that TENS was perceived to be significantly more comfortable than local anesthesia.[9] However, 2% lignocaine was perceived to be more effective, but 93.3% of the patients still preferred TENS, and would use it again. The reason being that TENS was non-invasive and discomfort from injection was not present as also the fact that there were no physiological objections and needle phobias were also eliminated.[17]

In this study, a significant reduction in pain was observed during all the dental procedures conducted under TENS, even though comparable with 2% lignocaine injection, and the patient was more comfortable when TENS was used. Thus, TENS should be considered as a useful adjunct in the treatment of pediatric patients during various minor dental procedures. But, it has got certain limitations and is contraindicated in patients with[18]

Pace makers

Heart disease

Epilepsy

Conclusion

TENS is any time better in eliminating the fear of pain due to dental injection and has the advantage of being non-invasive and safe to handle. It eliminates the inconvenience of a post-operative anesthetic effect, helps in maintaining infection control and avoids all the possible side-effects commonly associated with other anesthetic agents used through injection. Last but not the least, its efficacy is comparable with local anesthesia in minor pediatric dental procedures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Giangrego E. Controlling anxiety in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;113:728–35. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1986.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanism: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–8. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shane S M, Kessler S. Electricity for sedation in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1967;75:1369–75. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1967.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asarch T, Allen K, Petersen B, Beiraghi S. Efficacy of a computerized local anesthesia device in Pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:421–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund I, Lundeberg T, Sandberg L, Bund CN, Kowalski J, Svensson E. Lack of interchangeability between visual analogue and verbal rating pain scale: A cross sectional description of pain etiology groups. BMC Med Res Method. 2005;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabiston DC. 14th ed. USA: W.B. Saunders Publications; 1999. Textbook of Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkinson PS. 11th ed. ELBS Publications; 1997. Lee's synopsis of Anesthesia. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey M, Elliott M. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for pain management during cavity preparations in pediatric patient. ASDC J Dent child. 1995;62:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yap AU, Henry CW. Electronic and local anesthesia: A clinical comparison for operative procedures. Quintessence Int. 1996;27:549–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quarnstrom Fred. Electronic dental anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 1992;39:162–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanism: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–8. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benett CR. 7th Ed. CBS Publications and Distributors; 1990. Local anesthesia and pain control in dental practice. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul MN., St Patient comfort system Manual 3M. 1994:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop TS. High frequency neural modulation in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;112:176–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Segura A, Kanellis M, Donly KJ. Extra oral electronic dental anesthesia for moderate procedures in pediatric dentistry. J Dent. 1995;74:27. (Abst 123) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clerk SM, Silverstone LM, Lindermath J, Hicks MJ. An evaluation of the clinical analgesia /anesthesia efficacy on acute pain using the high frequency neural modulator in various dental setting. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;63:501–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jedrychowski JR, Duperon DF. Effectiveness and acceptance of electronic dental anesthesia by pediatric patient. J Dent Child. 1993;60:186–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malamed SF. 4th ed. Harcourt Brace and Company Asia PTE Ltd; 1998. Handbook of local anesthesia. [Google Scholar]