SUMMARY

Reducing protein synthesis slows growth and development but can increase adult life span. We demonstrate that knockdown of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G), which is downregulated during starvation and dauer state, results in differential translation of genes important for growth and longevity in C. elegans. Genome-wide mRNA translation state analysis showed that inhibition of IFG-1, the C. elegans ortholog of eIF4G, results in a relative increase in ribosomal loading and translation of stress response genes. Some of these genes are required for life span extension when IFG-1 is inhibited. Furthermore, enhanced ribosomal loading of certain mRNAs upon IFG-1 inhibition was correlated with increased mRNA length. This association was supported by changes in the proteome assayed via quantitative mass spectrometry. Our results suggest that IFG-1 mediates the antagonistic effects on growth and somatic maintenance by regulating mRNA translation of particular mRNAs based, in part, on transcript length.

INTRODUCTION

Protein synthesis is a regulated cellular process that plays a key role in keeping organismal growth and development in tune with environmental conditions (Sonenberg et al., 2000). In multiple species, genetic or dietary restriction-induced inhibition of protein synthesis slows growth but enhances life span (Syntichaki et al., 2007, Curran and Ruvkun, 2007, Pan et al., 2007, Hansen et al., 2007, Henderson et al., 2006, Steffen et al., 2008, Miller et al., 2005, Richie et al., 1994, Orentreich et al., 1993, Chen et al., 2007). Furthermore, screens for genes that reduce early fitness for life span extension in adults yielded a number of longevity genes, especially those involved in protein synthesis (Chen et al., 2007, Curran and Ruvkun, 2007). These results support the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging (Kapahi et al., 2010). However, the mechanisms by which growth and somatic maintenance are antagonistically related remain poorly understood. One possible mechanism for the antagonistic effects may lie in the differential mRNA translation effects of genetic and environmental perturbations that extend life span.

It was previously shown that differential mRNA translation is crucial during cellular responses to environmental stressors (Sonenberg et al., 2000, Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2007). During starvation, the mRNA of the yeast transcriptional regulator GCN4 is translated more efficiently due to an increase in translation initiation, though the overall rate of protein synthesis decreases under these conditions compared to well-fed conditions (Tzamarias et al., 1989, Hinnebusch, 2005). Its translation is enhanced due to the presence of short upstream open reading frames (ORFs) in the 5′UTR, which under well-fed conditions inhibit translation. This increase in translation is also important for slowing aging in S. cerevisiae. Increased GCN4 mRNA translation upon reduced 60S subunit abundance and upon glucose restriction partially mediates life span extension under these conditions (Steffen et al., 2008). Differential mRNA translation of various mRNAs was also observed upon dietary restriction as measured by genome-wide mRNA translation state analysis in D. melanogaster (Zid et al., 2009). Although dietary restriction decreased overall protein synthesis, a subset of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial subunits from complexes I and IV showed enhanced translation and were necessary for maximal life span extension under dietary restriction (Zid et al., 2009). These studies demonstrate the importance of taking into account the changes in mRNA translation state to understand the mechanisms that modulate stress responses and aging.

eIF4G acts as a scaffold for the highly conserved eIF4F capbinding complex that mediates cap-dependent translation initiation. It connects eIF4E, which binds the 5′ methylated cap, to poly-A binding protein (PABP), which associates with the poly-A tail, resulting in the circularization of mRNAs. eIF4G then recruits the 40S ribosomal subunit via its interaction with eIF3 (Hershey and Merrick, 2000). Inhibition of eIF4G, encoded by ifg-1 in C. elegans, results in decreased translation (Hansen et al., 2007, Pan et al., 2007) and a robust increase in life span (Hansen et al., 2007, Henderson et al., 2006, Pan et al., 2007, Curran and Ruvkun, 2007). We and others have shown that RNAi-mediated suppression of ifg-1 results in larval arrest during development (Pan et al., 2007, Long et al., 2002), but extends life span (Curran and Ruvkun, 2007, Hansen et al., 2007, Henderson et al., 2006, Pan et al., 2007) and increases resistance to starvation (Pan et al., 2007) if inhibited just during adulthood.

Increased resistance to certain stresses is also observed in other life span extension models, including insulin-like signaling (ILS) inhibition (Kenyon et al., 1993, Lithgow et al., 1994, Murakami and Johnson, 1996, Honda and Honda, 1999). Enhanced life span in this pathway is dependent upon activation of the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16. We previously showed that ifg-1 RNAi results in a small but reproducible extension of life span in a daf-16(mu86) null mutant (Pan et al., 2007), although another study did not observe the life span extension in this background (Hansen et al., 2007). These differences are likely to be the result of differences in the efficacy of ifg-1 RNAi, as both studies were done using daf-16(mu86). Additionally, a third study suggested that life span extension by inhibition of ifg-1 RNAi was DAF-16-independent if administered during development and DAF-16-dependent if administered during adulthood, although this study used a loss-of-function daf-16(m26) mutant rather than a null mutant (Henderson et al., 2006). Support for ifg-1 interacting in parallel to the ILS pathway also comes from the observation that inhibition of ifg-1 in daf-2 mutants leads to additive life span extension, though it is possible that this additive life span extension may be due to further inhibition of daf-2 upon reduction of ifg-1, as these were not null mutants. Thus, the mechanisms by which inhibition of ifg-1 extends life span and how it interacts with other longevity pathways remains poorly understood.

In this study, we investigated the mechanisms by which inhibition of ifg-1 extends life span using a genome-wide approach to study mRNA translation state (Arava, 2003, Zong et al., 1999, MacKay et al., 2004). Using translational profiling, we observed that ifg-1 inhibition results in significant differential changes in ribosome loading onto mRNA. Although translation was globally reduced, expression of certain longer-than-average mRNA-regulating stress responses and enhanced longevity was preferentially maintained relative to other mRNA. Inhibiting expression of some of these genes abrogated the enhanced life span and stress resistance when ifg-1 was reduced. A reduction of IFG-1 protein was observed upon dauer state (Bonawitz et al., 2007) and starvation, suggesting its role in adaptation under these conditions by inhibiting growth and enhancing somatic maintenance. Our data support the hypothesis that IFG-1 acts as a switch to mediate antagonistically pleiotropic effects between growth and somatic maintenance through differential mRNA translation.

RESULTS

Differential Regulation of Translation Occurs upon Inhibition of ifg-1

To determine whether gene expression is differentially regulated depending on ifg-1 expression, we performed translation state array analysis (TSAA) (Arava, 2003, Zong et al., 1999, MacKay et al., 2004, Rajasekhar et al., 2003, Trutschl et al., 2005, Dinkova et al., 2005). This method quantifies ribosomal loading of individual mRNAs. Since initiation is the rate-limiting step of translation, mRNA ribosomal density indicates the rate of translation. Wild-type N2 animals on day one of adulthood were fed bacteria expressing control (L4440) or ifg-1 dsRNA for 48 hr. RNAi was used because it shows a greater life span extension than the loss-of-function mutant ifg-1(cxTi9279). Changes in the distribution of ribosomes upon treatment with ifg-1 RNAi were quantified and showed an increase in free ribosomes (monosomes), indicative of reduced translation initiation (Figure S1). Differential mRNA translation was determined by changes in the translation index (TI)—the ratio of expression of mRNA for a particular gene in the highly translated mRNA fraction (defined as >5 ribosomes/transcript) to its expression in the low translation fraction (≤5 ribosomes/transcript) (Figure S2). TI values were calculated via microarray analysis, and differences in the translation status were plotted for all genes on the array (Figure 1A, left panel). The y axis represents the log ratio of gene expression in the high translation fraction for ifg-1 versus control RNAi, while the x axis represents the same, but for the low translation fraction. Genes plotted along the solid diagonal line exhibit equally changed high and low translation fractions and are thus unchanged with respect to ribosomal loading. Those plotted orthogonal to the solid line, along the dashed red line, reflect a change in TI and are thus differentially translated. Of 18,870 genes tested (C. elegans genome contains ~20,000 genes) and using a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 (see Experimental Procedures), we found 722 genes that were differentially translated, including 412 exhibiting increased TI and 310 with decreased TI (i.e., a relative increased or decreased propensity for translation initiation, respectively) (Figure 1A, right panel).

Figure 1. Inhibition of ifg-1 Differentially Regulates Gene Expression at the Level of Translation.

(A) Genome-wide comparison of relative expression in low (L) versus high (H) translation fractions (left panel). Coordinates correspond to the log2 of the ratio of gene expression between conditions (ifg-1 RNAi: control RNAi) for the translated fractions. The right panel shows the relative expression in low (L) versus high (H) translation fractions for genes selected on the basis of significantly altered TI.

(B) Cluster image map of genes with altered TI versus their inclusion among overrepresented GO categories. Red indicates upregulation when ifg-1 is inhibited, and blue indicates downregulation. The plot represents 250 genes with altered TI present at the greatest frequency among the 100 most significantly overrepresented GO categories.

(C) Overrepresented biological GO categories showing the number of genes in each category and the statistical significance. The p value indicates significantly overrepresented categories in yellow, while orange boxes indicate the parent terms (i.e., the ontological lineage). A total of 8179 genes were tagged withGOterms falling under the heading of “Biological process.”

(D) Cluster analysis of TI genes, representing the level of coregulation for each gene with every other gene (722 plotted along both the x axis and y axis). Red, yellow, green, blue, and purple colors indicate high-to-low level of coregulation among genes with significantly altered TI, respectively.

Gene ontological (GO) enrichment analysis identified numerous overrepresented biological processes among genes with significantly altered TI (Table S1). To simplify this list, we performed clustered image mapping (Weinstein et al., 1997), which takes overrepresented GO categories and clusters them with differentially translated genes they have in common (Figure 1B). Red and blue colors indicate upregulation and downregulation, respectively. The large red box in the lower left corner of Figure 1B shows 13 overrepresented categories on the x axis (in bold in Table S1) associated with 38 differentially translated genes on the y axis. The largest GO category in this group was the “response to stress” class which overlapped with two other overrepresented categories: cellular homeostasis and aging (Figure 1C) (full stress response gene list includes 51 genes described in Table S2). To test the level of coregulation among differentially translated genes, we performed cluster analysis of the 722 differentially regulated genes. Most differentially translated stress response genes were upregulated and represented in the highly coregulated subcluster outlined by the dashed box in Figure 1D. Although previously identified aging-related genes in C. elegans are usually negative regulators of life span, 16 of 17 of those found in the highly coregulated subcluster in Figure 1D have either been shown or are inferred to positively regulate life span. Furthermore, 14 of these were translationally upregulated (Table S3). Thus, reduced ifg-1 expression results in preferential maintenance of certain genes, which may help explain its associated phenotypes of extended life span and resistance to starvation stress.

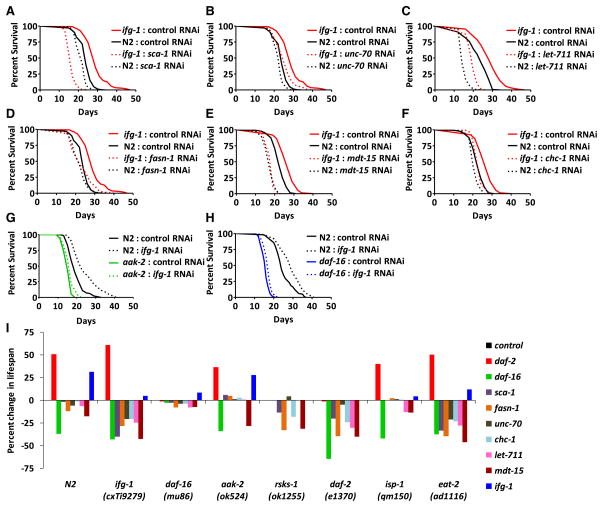

Certain Differentially Translated Genes Mediate the Life Span Extension upon ifg-1 Inhibition

We analyzed 40 highly coregulated differentially translated stress response genes from Table S2 showing upregulation from TSAA results, using RNAi clones (Fraser et al., 2000) to determine their biological significance with respect to life span in the ifg-1(cxTi9279) background or upon RNAi of ifg-1. Reduced expression of eight genes including sca-1, unc-70, let-711, fasn-1, mdt-15, chc-1, daf-16, and aak-2 suppressed life span upon ifg-1 inhibition (Figures 2A–2H), which was consistent with their expression pattern. RNAi clone identities were confirmed by DNA sequencing, and the RNAi-mediated knock-down of targeted genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure S3).

Figure 2. Translationally Upregulated Stress Response Genes Are Important for Life Span Extension upon ifg-1 Inhibition.

(A) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 29.0 days (n = 110) on control RNAi; 16.1 days (n = 69) on sca-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 23.6 days (n = 274) on control RNAi; 21.4 days (n = 143) on sca-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(B) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 29.0 days (n = 110) on control RNAi; 25.3 days (n = 106) on unc-70 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 23.6 days (n = 274) on control RNAi; 22.1 days (n = 142) on unc-70 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(C) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 28.3 days (n = 107) on control RNAi; 19.8 days (n = 119) on let-711 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 22.9 days (n = 140) on control RNAi; 15.3 days (n = 160) on let-711 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(D) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 29.0 days (n = 110) on control RNAi; 23.4 days (n = 132) on fasn-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 23.6 days (n = 274) on control RNAi; 21.9 days (n = 232) on fasn-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(E) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 27.2 days (n = 73) on control RNAi; 18.5 days (n = 119) on mdt-15 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 22.6 days (n = 144) on control RNAi; 17.7 days (n = 160) on mdt-15 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(F) Mean life span for the ifg-1(cxTi9279) mutant was 27.2 days (n = 73) on control RNAi; 23.7 days (n = 112) on chc-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 22.6 days (n = 144) on control RNAi; 21.0 days (n = 83) on chc-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(G) Mean life span for the aak-2 (ok524) mutant on control RNAi was 15.7 days (n = 72); 17.3 days (n = 61) on ifg-1 RNAi (p = 0.0014). Mean life span for N2 was 19.7 days (n = 81) on control RNAi; 24.8 days (n = 80) on ifg-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(H) Mean life span for the daf-16 (mu86) mutant on control RNAi was 15.6 days (n = 126); 16.9 days (n = 137) on ifg-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001). Mean life span for N2 was 25.4 days (n = 98) on control RNAi; 28.7 days (n = 98) on ifg-1 RNAi (p < 0.0001).

(I) Life span pathway dependence on stress response genes was determined for ifg-1, rsks-1, daf-2, isp-1, eat-2, daf-16, and aak-2 mutants. Results are given as the percent change in life span for each RNAi treatment (corresponding to Table S4). All life spans were repeated at least one time. Complete statistical analysis can be found in Table S4.

Our analysis showed that two genes, sca-1 and mdt-15, were essential for life span extension. On average, ifg-1 mutants lived 22.6% longer than N2 on control RNAi. Life span in the ifg-1 mutant was reduced to less than control animals when sca-1 was inhibited using RNAi (Figure 2A). This gene encodes a sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium-dependent ATPase that helps regulate calcium homeostasis and is required for development and muscle function. The human ortholog is associated with Darier-White disease, and a 50% reduction in molecular activity is found in patients with Brody myopathy (Benders et al., 1994). mdt-15 encodes a subunit of the mediator complex that acts as a coactivator of transcription. Reducing mdt-15 expression shortened the life span of the ifg-1 mutant to that of the control animals (Figure 2E). It was previously reported that mdt-15 is necessary for normal life span (Taubert et al., 2006) and mediates expression of metabolic genes under normal and starvation conditions (Taubert et al., 2008). Here, we observe that mdt-15 is also necessary for life span extension when ifg-1 is inhibited.

Expression of unc-70, fasn-1, and chc-1 also contributed to the life span extension upon inhibiting ifg-1 (Figures 2B–2D and 2F). unc-70 encodes β-spectrin, a major component of the plasma membrane important for cell polarity and localization of α-spectrin (Hammarlund et al., 2000). Inhibition of unc-70 reduced life span to a greater extent in ifg-1 mutants than in N2 (12.8% reduction in ifg-1 compared to 6.4% in N2) (Figure 2B). fasn-1 encodes a putative fatty acid synthase orthologous to human FASN (fatty acid synthase) that supports synthesis of membrane lipids (D’Erchia et al., 2006). RNAi of fasn-1 reduced life span in the ifg-1 background by 19.3% compared to 7.2% in wild-type (Figure 2D). chc-1 (clathrin heavy chain) encodes the heavy chain of the vesicle coat protein clathrin and is important for receptor-mediated yolk endocytosis (Grant and Hirsh, 1999). RNAi of this gene reduced ifg-1 life span by 12.9% and only by 7.1% in N2 (Figure 2F). Results suggest that there is a partial suppression of life span extension by inhibiting ifg-1 upon knocking down unc-70, fasn-1, and chc-1. RNAi of let-711, originally identified based on defective mitotic spindle positioning and later characterized as a negative regulator of zyg-9 (DeBella et al., 2006), resulted in a 30.0% reduction in life span of ifg-1 animals compared to 33.2% in N2 (Figure 2C), suggesting a more general role in normal life span.

aak-2, which encodes the catalytic subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase (Apfeld et al., 2004), was differentially upregulated and, thus, investigated for its importance in life span extension when ifg-1 is inhibited. The effects of aak-2 RNAi were minimal, possibly due to a lack of RNAi penetrance. RNAi of ifg-1 resulted in a 10.2% extension in life span in the aak-2(ok524) null mutant compared to control RNAi (Figure 2G). daf-16, which encodes a FOXO transcription factor essential for life span extension through the ILS pathway (Kimura et al., 1997, Lin et al., 1997), was also differentially upregulated under ifg-1 inhibition. Inhibition of ifg-1 using RNAi was able to induce a small but consistent life span extension in a daf-16(mu86) null background (8.3%) (Figure 2H). Together, these experiments suggest a partial dependence on aak-2 and daf-16 for enhanced longevity upon inhibition of ifg-1 and, furthermore, that this life span extension is mediated by the combined effects of longevity and stress response genes that are differentially regulated under this condition.

We wondered whether the stress response genes important for life span when ifg-1 is inhibited, particularly sca-1 and mdt-15, would also be critical in other genetic models of longevity. Figure 2I shows the relative life span in various mutant backgrounds under different RNAi conditions. In addition to the stress response genes, we also included effects of RNAi-mediated suppression of daf-2 and ifg-1 for each background. The life span results and the statistics can be found in Table S4. Neither mdt-15 nor sca-1 was essential for the life span extension in a daf-2 (e1370) mutant. Life span was decreased by 20.2% and 39.9% in daf-2(e1370) upon RNAi of sca-1 and mdt-15, respectively (Table S4). However, when compared with N2 on these treatments, the daf-2(e1370) mutant maintained 68.6% of its relative ability to extend life span upon sca-1 inhibition and 54.6% of its life span benefit upon mdt-15 inhibition. Similarly, inhibition of sca-1 or mdt-15 only partially reduced life span extension in another model of extended life span involving translational attenuation, in which the ribosomal S6 kinase gene, rsks-1 (Pan et al., 2007), is knocked out (Figure 2I). Interestingly, mtd-15 RNAi had a comparable effect in an eat-2(ad1116) mutant, a genetic model of dietary restriction (Hansen et al., 2007), to that of the ifg-1 mutant, reducing life span in that background to wild-type levels (Figure 2I). sca-1 RNAi also dramatically reduced life span in the eat-2 mutant (33.4% overall reduction, corresponding to only 9.3% life span benefit relative to N2 on this treatment) (Figure 2I). Thus, life span extension through ifg-1 inhibition or dietary restriction may result from partially overlapping mechanisms. Attenuation of sca-1 or mdt-15 had a small effect in a genetic model of enhanced longevity involving mitochondrial dysfunction, isp-1(qm150) (Feng et al., 2001) (Figure 2I). Interestingly, expression of fasn-1 was crucial for the life span extension in the rsks-1(ok1255) mutant (Figure 2I), which is different from the ifg-1 background, where its reduction results in an incomplete suppression of the life span extension. With the exception of fasn-1, the genes tested here tended to be more specific for life span extension upon ifg-1 inhibition than in other genetic models for enhanced longevity.

High-Resolution Translation Profiling Corroborates Translational Efficiency Measured by the TI

To better resolve the altered distribution of stress response mRNA given by the TI, high-resolution profiling experiments were conducted by separating polysomes into six fractions. The first fraction contains mRNAs with few attached ribosomes and represents a low rate of translation. Each subsequent fraction contains more attached ribosomes and thus represents a higher rate of translation on a per transcript basis. Figure 3 shows a characteristic translation profile of nematodes on control RNAi (gray line) overlaid with a profile of those on ifg-1 RNAi (black line with red highlight). As in earlier experiments, when ifg-1 is inhibited for 48 hr during early adulthood, low mRNA translation is reflected in the reduced area under the polyribosome portion of the translation profile. Below the profile are average genespecific expression ratios (ifg-1: control) across fractions from three experiments performed. The expression profile for sca-1 indicates a peak in the difference of expression in translation fraction 5, which is the peak of the high translation range. Overall, stress response gene expression showed an upward trend from low to high translation fractions, supporting estimates of changes in translation from TI values. Four genes, including rsp-1 and T19B4.5 (Figure 3), as well as daf-21 and ketn-1 (Figure S4), were included for comparison as examples of genes with significantly diminished TI under ifg-1 inhibition. In total, high-resolution translation profiles for ten genes, six with increased TI and four with diminished TI, were analyzed in three separate experiments. The trends in the high-resolution profiling were generally well matched with their respective TI values for the majority of genes tested (Figure 3), except for chc-1 (Figure S4).

Figure 3. High-Resolution Polysomal Profiles of Individual Stress Response Genes upon ifg-1 Inhibition.

Individual expression profiles for stress response genes important for life span are shown for the polysome region after 48 hr of control (gray line) or ifg-1 (black line highlighted in red) RNAi feeding. The average relative expression ratio between these two conditions (ifg-1 RNAi: control RNAi) and standard error of the mean (SEM) are shown for three independent experiments. Fractions were standardized according to Coleoptera luciferase control RNA spiking. Gene expression values for each fraction were then normalized according to the average expression value for that fraction. The ratio of TI values (ifg-1 RNAi to control RNAi conditions) associated with each gene is listed directly below the gene name, with values greater than one indicating an increase in translation state upon ifg-1 inhibition. Characteristic profiles for worms on control RNAi and ifg-1 RNAi are shown for one experiment to illustrate where relative expression is measured.

IFG-1 Is Downregulated under Nutrient-Limitation Conditions and Modulates Survival under Starvation

Enhanced resistance to various stressors is often observed in long-lived mutants, supporting the idea that increased somatic maintenance can prolong life span. Inhibition of ifg-1 results in enhanced survival upon starvation (Pan et al., 2007). We tested whether the stress response genes important for life span are also required for the increased survival under starvation in the ifg-1 mutant. RNAi suppression of tested stress response genes diminished the survival upon starvation in ifg-1 mutant (Figure 4A and Table S5), whereas the effects in the control strain were generally either small or nonexistent except for mdt-15 (Figure 4B and Table S5). Given the enhanced survival upon starvation of ifg-1 mutant animals, we examined whether wild-type animals modulate IFG-1 levels during starvation in order to enhance somatic maintenance. IFG-1 levels were measured in starved wild-type N2 worms, using antibodies raised against IFG-1 (Contreras et al., 2008). IFG-1 was reduced in worms starved for 2 days (Figures 4C and 4D), with even lower levels by day three (Figure S5). We previously demonstrated that ifg-1 transcript levels are significantly decreased under dauer conditions (Pan et al., 2007). Hence, the observations that IFG-1 levels are reduced under starvation and dauer conditions and that inhibition of ifg-1 can upregulate stress response gene expression lend support to the idea that ifg-1 plays an important role in maintaining cellular homeostasis in response to changing environmental conditions. Inhibition of ifg-1 during development leads to larval arrest (Pan et al., 2007, Long et al., 2002), and inhibition during adulthood leads to a decrease in fecundity (Pan et al., 2007, Hansen et al., 2007). Taken together, findings suggest that IFG-1 acts as a switch to alter gene expression from growth and reproduction to somatic maintenance in response to nutrient fluctuations in the environment.

Figure 4. Differentially Translated Genes Are Important for Resistance to Starvation Stress, which Diminishes ifg-1 Expression.

(A and B) Individual stress response genes upregulated upon ifg-1 inhibition and important for life span were attenuated via RNAi feeding for 48 hr prior to starvation in the ifg-1 mutant (A) and wild-type N2 backgrounds (B).

(C) The P170 form of IFG-1 required for cap-mediated mRNA circularization was resolved by western blotting after 48 hr of feeding or fasting.

(D) Densitometry results for IFG-1 levels from three biological replicates after 48 hr of fasting or feeding are shown. All experiments were started on the first day of adulthood. Quantitation of IFG-1 was normalized to β-actin. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

The Expression Pattern of Differentially Regulated Genes Corresponds to mRNA Length

To investigate potential mechanisms behind the coregulation of differentially translated genes, we analyzed their mRNA structures in silico. Upon examination of the untranslated regions (UTRs), which are known to affect translation efficiency (Sonenberg, 1993), we found that the average 3′UTR length for translationally upregulated genes was more than double that of downregulated genes or the array average (Figure 5A and Table 1), while analysis of 3′UTRs for conserved motifs, such as AU-rich elements that are known to regulate translational gene expression, did not show significant differences between upregulated, downregulated, or unchanged genes. In addition, there were no significant changes in the folding energy and only a slight increase in GC content of the 3′UTRs for posttranscriptionally upregulated genes (Table 1). Although 5′UTRs are usually trans-spliced in C. elegans (Bektesh and Hirsh, 1988), roughly one third are not (Blumenthal and Steward, 1997). Analysis of nonsplice-leader 5′UTRs showed that, as with the 3′UTR, there was a tendency for greater 5′UTR length associated with mRNAs showing translationally upregulated expression upon ifg-1 inhibition (Table 1). Examination of ORFs also showed a similar pattern (Figure 5B). To test this connection further, we looked at the association of ORF length and TI by plotting the locally weighted least-squares (Lowess) smooth probability of these parameters for all genes in the array. ORF length was used instead of mRNA transcript length because more complete data are available for the coding portion of genes. Starting with genes having ORFs greater than the array average of about 1256 bases (approximately 34% of all genes) (Figure 5C), we found a steady increase in the TI as ORF increases when ifg-1 is suppressed (Figure 5D, green line, left axis). A similar regression of the p value for the TI of each gene also varies according to length, with longer ORFs associated with increased significance (Figure 5D, blue line, right axis). Results in Table 1 and Figure 5 suggest that overall transcript length may play a role in mediating the association of mRNAs with ribosomes, which can be altered by modulating levels of IFG-1.

Figure 5. UTR and ORF Length Is Associated with Altered Ribosomal Loading upon Suppression of ifg-1.

(A) Comparison of average 3′UTR length between translationally upregulated and downregulated genes. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. “Array” for the blue bar indicates all genes on the microarray.

(B) Comparison of average ORF length between translationally upregulated and downregulated genes. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

(C) Histogram indicating the number of genes with the ORF length indicated. The bracketed area shows that, starting from average ORF length for all genes on the microarray, 34% of genes are subject to differential posttranscriptional regulation based on ORF length.

(D) Lowess smooth plot of the ratio of TI (ifg-1 RNAi: control RNAi) and p value versus ORF length for the entire array.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Genes that Show Altered Ribosomal Binding upon Inhibition of ifg-1

| Increased TI

|

Decreased TI

|

Array Average TI

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | n | SEM | Average | n | SEM | Average | n | SEM | |

| 5′UTR lengtha | 79.8 | 238 | ±23.994 | 36b | 180 | ±4.056 | 49.6 | 8417 | ±1.170 |

|

| |||||||||

| 5′UTR fractional GC content | 0.415c | 238 | ±0.012 | 0.334 | 180 | ±0.015 | 0.364 | 8417 | ±0.002 |

|

| |||||||||

| 5′UTR ΔG (kcal/mol) | −5.31c | 163 | ±0.454 | −2.52 | 111 | ±0.430 | −1.73 | 5908 | ±0.034 |

|

| |||||||||

| 3′UTR length | 339.6c | 299 | ±15.791 | 149.1c | 208 | ±10.960 | 187 | 9667 | ±1.963 |

|

| |||||||||

| 3′UTR fractional GC content | 0.32c | 299 | ±0.004 | 0.277 | 208 | ±0.007 | 0.289 | 9667 | ±0.001 |

|

| |||||||||

| 3′UTR ΔG (kcal/mol) | −4.01 | 295 | ±0.212 | −3.48 | 204 | ±0.191 | −3.77 | 9449 | ±0.035 |

Length in nucleotides. 5′UTR is often transspliced and sequence information is often truncated (Wormbase release 180).

p < 0.01 in a two-tailed t test compared with the array average.

p < 0.001 in a two-tailed t test compared with the array average.

To determine whether the relationship between ORF length and mRNA translation changes were also reflected in the proteome, we utilized quantitative mass spectrometry according to an iTRAQ multiplexed protein quantitation strategy (Ross et al., 2004). Proteins from 928 genes were identified and 85 of the most significantly altered proteins upon ifg-1 inhibition were analyzed. The average amino acid length for proteins with increased expression was twice that of those with diminished expression (Figure 6A and Table S6). Ribosomal proteins, which are present at high levels and which tend to be smaller than the average protein, were diminished and contributed to the smaller average length of proteins whose expression was significantly reduced. The average length for proteins with lowered expression was 356 aa (n = 37). Excluding ribosomal proteins, the average length for proteins with lowered expression was 457 aa (n = 22). The average length of proteins with increased expression was 775 aa (n = 48). Among proteins with greater relative expression was SCA-1, in agreement with results from translation profiling experiments. The status of DAF-21, a member of the Hsp-90 family and among proteins with decreased concentration, was also in agreement with translation profiling results. Although translation profiling cannot account for effects of protein turnover, no examples of contradictory results were found between profiling experiments and the iTRAQ quantitation. On the other hand, given the bias toward finding the most abundant proteins in mass spectrometry, it is not surprising that a number of the genes we identified from translation state experiments were not observed in the quantitative proteomic experiment. Importantly, measurement of changes in translation by two methods, polysomal profiling and quantitative mass spectrometry, both suggest enhanced mRNA translation of genes with longer ORF length or total mRNA length when ifg-1 is inhibited.

Figure 6. Biochemical and Bioinformatics Analyses Point to Differential Changes in Protein Expression According to Message Length When ifg-1 Is Attenuated.

(A) Results of quantitative mass spectrometry of protein lysates comparing adult nematodes fed on control RNAi with ifg-1 RNAi for 2 days. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of changes in aa (amino acid) length of genes that were increased or decreased upon ifg-1 inhibition.

(B) Bioinformatic analysis of the relationship between ORF length and GO categories. Genes were separated on the basis of ORF length (bases) into five bins containing an equal number of genes. The ORF lengths for bins 1–5 are 0–522, 523–873, 874–1101, 1102–1587 and 1588–39300, respectively. From each bin, the total number of those corresponding to “Biological process” GO categories of stress response, translation, and ribonucleotide biosynthesis were compared with the average representation for all GO categories containing more than 100 genes (220 categories total).

The link between mRNA length, differential translation, and biological ontology upon ifg-1 suppression is of interest due to the potential consequences to cellular homeostasis. We further examined the link between ORF length and biological function by partitioning array genes into five groups based on ORF length, such that an equal number of genes was in each group. Over half of the genes in the “response to stress” GO category were present among the 20% of array genes with the longest ORFs (Figure 6B, genome bin 5). Since genes with longer ORFs may also contain more functional domains, we compared this result with the average representation of biological categories containing 100 or more genes across these partitions. While the average number of genes represented among categories increased with ORF length, the representation of stress response genes among those with the longest ORFs was substantially greater (36.9% for the average and 62.1% for stress response). Genes in the GO categories of translation (GO:0006412) and ribonucleotide biosynthetic process (GO:0009260) were used as proxies to test whether genes necessary for the most basic functions of growth and development showed an ORF length tendency. The greatest number of translation and ribonucleic biosynthetic process genes were significantly overrepresented among the 20% of array genes with the shortest ORFs (Figure 6B). Together with UTR analysis in Figure 5 and Table 1, these results suggest that certain classes of genes involved in growth and reproduction tend to have smaller message length, while many involved in stress responses tend to be longer in C. elegans.

DISCUSSION

Williams postulated the existence of antagonistic pleiotropic genes that endow benefits early in life at the cost of deleterious effects later to explain the evolution of senescence (Williams, 1957). In support of this idea, two studies in C. elegans previously identified a number of genes essential during development that could extend life span when inhibited during adult life (Curran and Ruvkun, 2007, Chen et al., 2007). IFG-1 is essential in C. elegans, as its inhibition during development leads to growth arrest (Long et al., 2002), while inhibition in adulthood extends life span (Hansen et al., 2007, Pan et al., 2007, Curran and Ruvkun, 2007, Henderson et al., 2006). Our experiments support the notion that changes in IFG-1 activity may have evolved to determine life span by antagonistically modulating growth and somatic maintenance functions. It is likely that regulating eIF4G levels serves as a mechanism to modulate the rate of protein synthesis in response to environmental cues. In S. cerevisiae, eIF4G degradation is observed when yeast cells undergo a diauxic shift (Berset et al., 1998). We have previously observed a decrease in ifg-1 expression during the stress-resistant/growth-arrested dauer state in C. elegans (Pan et al., 2007). Here we demonstrate that starvation also reduces the level of IFG-1 in C. elegans. Inhibition of cap-dependent translation by decreasing eIF4G may therefore be a conserved response that enhances survival under these conditions.

To study the mechanisms by which IFG-1 inhibition extends life span and increases resistance to starvation, genome-wide analysis of the translation state was used to measure changes in mRNA translation. Differential mRNA translation has been shown to play an important role in coping with starvation and heat stress (McColl et al., 2010, Joshi-Barve et al., 1992, Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009, Sonenberg et al., 2000), and our study showed that a number of genes involved in stress responses and aging are differentially translated when IFG-1 is reduced. Certain genes whose translation was preferentially maintained also played a key role in mediating life span extension upon inhibition of ifg-1. Furthermore, the role of these genes was mostly specific to life span extension via ifg-1 inhibition compared to other long-lived mutants. Results are consistent with previous observations demonstrating that ifg-1 inhibition extends life span in a manner not entirely dependent on other known life span models (Pan et al., 2007). Although a complete dependence on the ILS signaling pathway was observed in another study (Hansen et al., 2007), we suggest that this may be a result of differences in the level of inhibition of ifg-1 via RNAi.

The specificity of the stress response genes tested here for life span mediated by ifg-1 inhibition, compared with other longevity mutant models, was especially notable for sca-1, which was essential for life span in the ifg-1 background. Due to its intracellular localization, results point to a role for the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in extended life span when ifg-1 expression is inhibited. The connection between ER function and attenuation of translation through ifg-1 inhibition may be explained, in part, by a study that showed translation is compartmentalized to the ER during physiological inhibition of cap-dependent translation initiation (Lerner and Nicchitta, 2006). Usually ribosomes are released from the ER upon translation termination, but when cap-dependent translation was reduced through cleavage of eIF4G/IFG-1 and PABP by Coxsackie B virus in a human cell line, translation in the ER was maintained to a greater extent than in the cytosol, and ribosomes tended to stay associated with the ER. These results suggest the importance of calcium homeostasis via SCA-1 in the ER for extended life span when ifg-1 is inhibited. Alternatively, SCA-1 may be serving an additional and, as yet, unknown role in the ER with respect to life span extension via ifg-1 inhibition.

Attenuated expression of ifg-1 reduced ribosomal loading of short mRNAs to a greater extent than that of long mRNAs. This results in a relative increase in translational efficiency of longer mRNA, but this effect, though large in scale, does not discount effects on translation due to differences in undefined cis-regulatory elements. The changes in translation efficiency due to transcript length are modest and happen in a background of strongly repressed overall translation. However, the number of genes important for responding to stress and enhancing longevity suggests large scale remodeling of posttranscriptional gene expression that would likely affect the proteome, shifting the balance toward increased somatic maintenance. In support of this idea, quantitative mass spectrometry showed increased abundance of proteins with longer primary structure compared with shorter ones. It is important to note that TSAA and proteomic studies are likely to identify different genes due to inherent bias in the two methods. The TSAA method is more likely to identify less abundant mRNAs that undergo a shift in ribosomal loading, while the mass spectrometry methods are likely to detect more abundant proteins that are altered. Interestingly, genome-wide bioinformatics analysis of ORF length and gene function suggest that stress response genes tend to possess longer ORFs, while genes involved in positively regulating growth possess smaller ORFs. Our data support the idea that IFG-1 mediates a switch between growth and somatic maintenance, in part, by regulating mRNA translation based on ORF length. It is not obvious why stress response genes would possess longer ORFs. However, the evolutionary process of gene length extension is recognized as being of fundamental importance to the complexity of gene function and to the creation of new genes (Long et al., 2003). It has been proposed that natural selection favors shorter genetic coding sequence length for higher transcriptional efficiency, efficient protein synthesis, and the avoidance of deleterious mutation accumulation. However, imparting new or improved functions to a protein usually requires elongating its coding sequence (Zhang, 2000, Akashi, 2003, Claverie and Ogata, 2003). We speculate that longer genes in eukaryotes are important for responding to changing environmental conditions and evolved later in time than those necessary for the most basic functions of growth and reproduction. Given studies showing a high level of conservation of protein sequence length among orthologs in disparate forms of life, it is likely that our observations are relevant for understanding mechanisms of antagonistic pleiotropy across species.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Nematode Culture and Strains

C. elegans strains were cultured and synchronized as previously described (Chen et al., 2007, Chen et al., 2009). Strains included wild-type N2, ifg-1(cxTi9279), daf-16(mu86), aak-2(ok524), rsks-1(ok1255), eat-2(ad1116), isp-1(qm150), and daf-2(e1370). All strains were outcrossed six or more times and kept at 20°C. An expanded description is provided in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

RNAi Experiments

RNAi bacteria strains were cultured and utilized as previously described (Kamath et al., 2001). Nematodes at the L4 stage of development were transferred to plates containing 50 μg/ml 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FUdR) to equilibrate development and inhibit egg production. After 24 hr, nematodes were transferred to RNAi bacterial plates (spotted the day before and kept at 20°C) as day-one adults in the presence of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 25 μg/ml carbenicillin, and 50 μg/ml FUdR. All steps were carried out at 20°C.

Polysomal (Translation) Profiling

Worms at day three of adulthood were used to generate polysomal profiles. Reagents and processing were as previously described (Pan et al., 2007) (See expanded description in Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

RNA Extraction for Array and RT-PCR Analysis

TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) was used to extract RNA from liquid fractions according to the manufacturer’s protocol. QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis. Quantitative PCR was carried out using the Universal ProbeLibrary Set (Roche) and the LightCycler 480 II (Roche). Relative-fold changes for all qRT-PCR experiments performed were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Expression was standardized by spiking TRIzol with 20ng/ml Coleoptera luciferase control RNA (Promega). A more detailed description is available in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Microarrays and Data Processing

Oligo-based whole genome chips were purchased from Washington University (http://genome.wustl.edu/projects/celegans/microarray/index.php) and hybridized by the Buck Institute Genomics core. Benjamini and Hochberg’s method of FDR was used to determine adjusted q values (<0.05) based on four biological replicates. Detailed equations for data processing are available in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Bioinformatics Analysis of Differentially Translated Genes

GO analysis was performed using the GoToolBox and the GoMiner High Throughput (Zeeberg et al., 2005) web interface. Free folding energy was calculated using DINAMelt (Markham and Zuker, 2005). UTRs were analyzed for known RNA structures using RNA Analyzer (Bengert and Dandekar, 2003).

Life Span Analysis

Life span analyses were performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2009), using RNAi conditions noted in RNAi Experiments, above. Statistical analyses were performed using the Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were plotted for each life span and compared using the log rank test.

Starvation Stress Resistance

Adult worms were fed using the aforementioned RNAi treatments for 3 days. Worms used in the starvation experiments were suspended in 15 ml of sterile S basal and washed six times, allowing them to settle via sedimentation between each wash. Starvation conditions were created by placing washed worms on unspotted fresh NGM media plates made without peptone.

Western Blotting

Sample lysates were prepared in the same manner as those for polysomal profiling. SDS-PAGE and blotting were carried out using standard methods. Blots were probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-IFG-1 antibody (a kind gift from Brett Keiper) (Contreras et al., 2008) or rabbit polyclonal anti-β-actin antibodies (Cell Signaling). See additional description in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Samples analyzed consisted of 50 μg of worm protein lysate in 0.2% SDS and 1.0% Triton X-100 from each of four biological replicates of worms on control or ifg-1 RNAi. Trypsin-digested samples were labeled with iTRAQ 8-plex reagents according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Applied Biosystems). Results were processed using ProteinPilot software 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) with background correction and bias correction employed. Peptides of confidence greater than 50% were used for protein quantification. A 95% confidence (unused prot score > 1.3) threshold for protein identification established by ProteinPilot 3.0 was the criteria for inclusion into the final protein report. More detailed description of this protocol is available at the end of the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Brett D. Keiper and Robert E. Rhoads for the IFG-1 antibody used in this study. Some nematode strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, funded by NIH National Center for Research Resources. This work was funded by a T32 NIH training grant (AG000266) fellowship (A.R.), grants from the Ellison Medical Foundation, American Foundation for Aging Research, Hillblom Foundation, an institutional Nathan Shock Grant, which supported the Genomics core as well as a startup award (AG025708), and the NIH (RL1AAG032113, 3RL1AG032113-03S1).

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

Microarray data are posted with NCBI series accession number (GSE28665).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes five figures, six tables, Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and Supplemental References and can be found with this article online at doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.010.

References

- Akashi H. Translational selection and yeast proteome evolution. Genetics. 2003;164:1291–1303. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J, O’Connor G, McDonagh T, DiStefano PS, Curtis R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3004–3009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arava Y. Isolation of polysomal RNA for microarray analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;224:79–87. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-364-X:79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bektesh SL, Hirsh DI. C. elegans mRNAs acquire a spliced leader through a trans-splicing mechanism. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:5692. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.12.5692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benders AA, Veerkamp JH, Oosterhof A, Jongen PJ, Bindels RJ, Smit LM, Busch HF, Wevers RA. Ca2+ homeostasis in Brody’s disease. A study in skeletal muscle and cultured muscle cells and the effects of dantrolene an verapamil. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:741–748. doi: 10.1172/JCI117393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengert P, Dandekar T. A software tool-box for analysis of regulatory RNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3441–3445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berset C, Trachsel H, Altmann M. The TOR (target of rapamycin) signal transduction pathway regulates the stability of translation initiation factor eIF4G in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4264–4269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal T, Steward K. RNA Processing and Gene Structure. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 117–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz ND, Chatenay-Lapointe M, Pan Y, Shadel GS. Reduced TOR signaling extends chronological life span via increased respiration and upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression. Cell Metab. 2007;5:265–277. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Pan KZ, Palter JE, Kapahi P. Longevity determined by developmental arrest genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Thomas EL, Kapahi P. HIF-1 modulates dietary restriction- mediated lifespan extension via IRE-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claverie JM, Ogata H. The insertion of palindromic repeats in the evolution of proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:75–80. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras V, Richardson MA, Hao E, Keiper BD. Depletion of the cap-associated isoform of translation factor eIF4G induces germline apoptosis in C. elegans. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1232–1242. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SP, Ruvkun G. Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Erchia AM, Tullo A, Lefkimmiatis K, Saccone C, Sbisá E. The fatty acid synthase gene is a conserved p53 family target from worm to human. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:750–758. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.7.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBella LR, Hayashi A, Rose LS. LET-711, the Caenorhabditis elegans NOT1 ortholog, is required for spindle positioning and regulation of microtubule length in embryos. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4911–4924. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-02-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova TD, Keiper BD, Korneeva NL, Aamodt EJ, Rhoads RE. Translation of a small subset of Caenorhabditis elegans mRNAs is dependent on a specific eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E isoform. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:100–113. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.100-113.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Bussiére F, Hekimi S. Mitochondrial electron transport is a key determinant of life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2001;1:633–644. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Zipperlen P, Martinez-Campos M, Sohrmann M, Ahringer J. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Hirsh D. Receptor-mediated endocytosis in the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4311–4326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund M, Davis WS, Jorgensen EM. Mutations in beta-spectrin disrupt axon outgrowth and sarcomere structure. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:931–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ST, Bonafè M, Johnson TE. daf-16 protects the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans during food deprivation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:444–460. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey JWB, Merrick WC. The pathway and mechanism of initiation of protein synthesis. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:407–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.031805.133833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y, Honda S. The daf-2 gene network for longevity regulates oxidative stress resistance and Mn-superoxide dismutase gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 1999;13:1385–1393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi-Barve S, De Benedetti A, Rhoads RE. Preferential translation of heat shock mRNAs in HeLa cells deficient in protein synthesis initiation factors eIF-4E and eIF-4 gamma. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21038–21043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Martinez-Campos M, Zipperlen P, Fraser AG, Ahringer J. Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0002. doi: 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P, Chen D, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Li PW, Thomas EL, Kockel L. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 2010;11:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RS, Nicchitta CV. mRNA translation is compartmentalized to the endoplasmic reticulum following physiological inhibition of capdependent translation. RNA. 2006;12:775–789. doi: 10.1261/rna.2318906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: An HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278:1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithgow GJ, White TM, Hinerfeld DA, Johnson TE. Thermotolerance of a long-lived mutant of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Gerontol. 1994;49:B270–B276. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.6.b270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long X, Spycher C, Han ZS, Rose AM, Müller F, Avruch J. TOR deficiency in C. elegans causes developmental arrest and intestinal atrophy by inhibition of mRNA translation. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1448–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M, Betrán E, Thornton K, Wang W. The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:865–875. doi: 10.1038/nrg1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay VL, Li X, Flory MR, Turcott E, Law GL, Serikawa KA, Xu XL, Lee H, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, et al. Gene expression analyzed by high-resolution state array analysis and quantitative proteomics: response of yeast to mating pheromone. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:478–489. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham NR, Zuker M. DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W577–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl G, Rogers AN, Alavez S, Hubbard AE, Melov S, Link CD, Bush AI, Kapahi P, Lithgow GJ. Insulin-like signaling determines survival during stress via posttranscriptional mechanisms in C. elegans. Cell Metab. 2010;12:260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Buehner G, Chang Y, Harper JM, Sigler R, Smith-Wheelock M. Methionine-deficient diet extends mouse lifespan, slows immune and lens aging, alters glucose, T4, IGF-I and insulin levels, and increases hepatocyte MIF levels and stress resistance. Aging Cell. 2005;4:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Johnson TE. A genetic pathway conferring life extension and resistance to UV stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1996;143:1207–1218. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orentreich N, Matias JR, DeFelice A, Zimmerman JA. Low methionine ingestion by rats extends life span. J Nutr. 1993;123:269–274. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan KZ, Palter JE, Rogers AN, Olsen A, Chen D, Lithgow GJ, Kapahi P. Inhibition of mRNA translation extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:111–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar VK, Viale A, Socci ND, Wiedmann M, Hu X, Holland EC. Oncogenic Ras and Akt signaling contribute to glioblastoma formation by differential recruitment of existing mRNAs to polysomes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:889–901. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie JP, Jr, Leutzinger Y, Parthasarathy S, Malloy V, Orentreich N, Zimmerman JA. Methionine restriction increases blood glutathione and longevity in F344 rats. FASEB J. 1994;8:1302–1307. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, et al. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N. Translation factors as effectors of cell growth and tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:955–960. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. New modes of translational control in development, behavior, and disease. Mol Cell. 2007;28:721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB. Translational control of gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen KK, MacKay VL, Kerr EO, Tsuchiya M, Hu D, Fox LA, Dang N, Johnston ED, Oakes JA, Tchao BN, et al. Yeast life span extension by depletion of 60s ribosomal subunits is mediated by Gcn4. Cell. 2008;133:292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syntichaki P, Troulinaki K, Tavernarakis N. eIF4E function in somatic cells modulates ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2007;445:922–926. doi: 10.1038/nature05603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert S, Van Gilst MR, Hansen M, Yamamoto KR. A Mediator subunit, MDT-15, integrates regulation of fatty acid metabolism by NHR-49-dependent and -independent pathways in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1137–1149. doi: 10.1101/gad.1395406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert S, Hansen M, Van Gilst MR, Cooper SB, Yamamoto KR. The Mediator subunit MDT-15 confers metabolic adaptation to ingested material. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trutschl M, Dinkova TD, Rhoads RE. Application of machine learning and visualization of heterogeneous datasets to uncover relationships between translation and developmental stage expression of C. elegans mRNAs. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21:264–273. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00307.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzamarias D, Roussou I, Thireos G. Coupling of GCN4 mRNA translational activation with decreased rates of polypeptide chain initiation. Cell. 1989;57:947–954. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein JN, Myers TG, O’Connor PM, Friend SH, Fornace AJ, Jr, Kohn KW, Fojo T, Bates SE, Rubinstein LV, Anderson NL, et al. An information-intensive approach to the molecular pharmacology of cancer. Science. 1997;275:343–349. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC. Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeberg BR, Qin H, Narasimhan S, Sunshine M, Cao H, Kane DW, Reimers M, Stephens RM, Bryant D, Burt SK, et al. High-Throughput GoMiner, an ‘industrial-strength’ integrative gene ontology tool for interpretation of multiple-microarray experiments, with application to studies of Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. Protein-length distributions for the three domains of life. Trends Genet. 2000;16:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zid BM, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Vargas MA, Kolipinski MC, Lu TA, Benzer S, Kapahi P. 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;139:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong Q, Schummer M, Hood L, Morris DR. Messenger RNA translation state: the second dimension of high-throughput expression screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10632–10636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]