Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effects of music therapy on depressive mood and anxiety in post-stroke patients and evaluate satisfaction levels of patients and caregivers.

Materials and Methods

Eighteen post-stroke patients, within six months of onset and mini mental status examination score of over 20, participated in this study. Patients were divided into music and control groups. The experimental group participated in the music therapy program for four weeks. Psychological status was evaluated with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) before and after music therapy. Satisfaction with music therapy was evaluated by a questionnaire.

Results

BAI and BDI scores showed a greater decrease in the music group than the control group after music therapy, but only the decrease of BDI scores were statistically significant (p=0.048). Music therapy satisfaction in patients and caregivers was affirmative.

Conclusion

Music therapy has a positive effect on mood in post-stroke patients and may be beneficial for mood improvement with stroke. These results are encouraging, but further studies are needed in this field.

Keywords: Music therapy, mood, stroke, depression, anxiety

INTRODUCTION

Music therapy appears to affect physiological phenomena such as blood pressure, heartbeat, respiration, and mydriasis as well as emotional aspects such as mood and feelings.1 Clinical studies in adults also demonstrated correlations between the physiological and emotional stimulation effects of music.2 Clair found that music induced adjustment of respiratory rhythm, relaxation of muscular stiffness, decrease of heart rate and blood pressure by formation of a comfortable atmosphere, and alleviation of tension by increased alpha waves in the brain, and bright showed significant effects of music on the reduction of depression and anxiety indices in patients with respiratory diseases, rehabilitation, and cranial nerve diseases.

Post-stroke depression is reported to be present in 32.9-35.9% of stroke patients, which is significantly higher than the prevalence of depression in the general population (10%).3,4 Post-stroke depression is known to be related to cognitive dysfunction and can have a negative influence on recovery of daily living (ADL) activities or be in close relationship to death.5-8 Early diagnosis and treatment of post-stroke depression can have a major effect on the final outcome.9 Major goals of treatment are to reduce depressive symptoms, improve mood and quality of life, and reduce the risk of medical complications as well as the relapse of post-stroke depression. However, antidepressants are generally not indicated in mild forms because the balance of benefit and risk is not satisfactory in stroke patients.10

The frequency of anxiety after stroke varies from study to study ranging from 21% to 28%,11-13 and prevalence and severity of anxiety symptoms are comparable to depression symptoms. Anxiety is found to have a relationship with quality of life in post-stroke patients.14

There are few studies with music therapy on mood in post-stroke patients, although music therapy has been used in rehabilitation to stimulate brain functions involved in emotion, cognition, speech and sensory perceptions.15

The goals of this study are to investigate the effects of music therapy on the mood of stroke patients and evaluate satisfaction levels of patients and caregivers after therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects in this study included 18 post-stroke patients, within six months of onset and mini mental status examination (MMSE) score of over 20, who were admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Gangnam Severance Hospital. All patients were receiving comprehensive rehabilitation treatment including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy. And all patients received regular counseling by licensed psychotherapist. The music group consisted of nine patients who volunteered for music therapy. We selected nine patients as a control group who were matched for age and MMSE score to patients in the experimental group. Both groups received the same comprehensive rehabilitation therapy. Nine patients in the music group underwent a total of eight music therapy sessions twice a week for four weeks while nine patients in the control group did not receive music therapy. Exclusion criteria were current alcohol or substance abuse and primary psychiatry diagnosis before stroke. The study was approved by local ethical committee.

The music therapy program in this study followed the 40-minute music therapy format and was carried out in accordance with the physical strength and individual characteristics of patients. The session consisted of a hello song and sharing of events in their lives (5 minutes); planned musical activities (30 minutes) including respiration and phonation, improvised play, hand bell play, singing, songwriting, and expression in tune with music; and sharing of feelings and a goodbye song (5 minutes). Keyboards, hand bells, percussion instruments, flutes, and other tools such as picture cards, flowers, and fruit scents were used in accordance with the planned activities. Patients were encouraged to improvise depending on their feelings and sing children's and folk songs.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) tests were performed for the music and control groups before and after treatment to determine the effect of music therapy on psychological status. A questionnaire was conducted on the change in psychological status after treatment and satisfaction level in patients who received music therapy and their caregivers.

Data analysis

Group differences in age, MMSE and pretest BAI/BDI score between groups were tested by t-test. In addition, differences in BDI and BAI between before and after treatment were analyzed with paired t-test. The level of statistically significance was set at p<0.05. All data were entered into the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS®, version 18.0).

RESULTS

The average age of the music group was 51.7±13.5 years. Eight of nine patients were males with a mean MMSE of 27.1±2.0. The average age of the control group was 47.3±11.7 years, and all the patients were male with a mean MMSE of 25.4±2.9. There were no significant differences in age and MMSE between the two groups. There were four patients in music therapy group who took antidepressants, and three patients in control group, with a ratio of 44% and 33%. The etiology of stroke was divided by hemorrhage and infarction. In music therapy group, three of nine patients' etiology was hemorrhage, and the other six patients' was infarction. In control group, five patients' etiology was hemorrhage, and the other four patients' etiology was infarction.

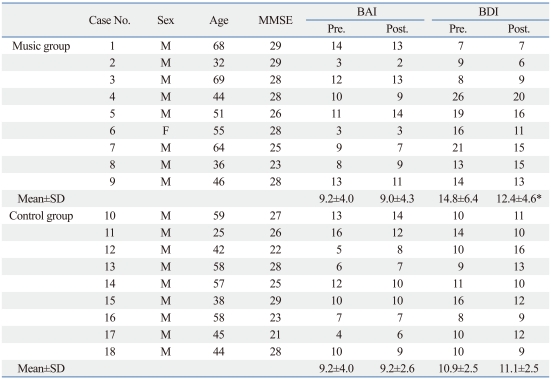

The mean BAI and BDI scores of the music group before music therapy were 9.2 and 14.8 and those of the control group were 9.2 and 10.9, respectively. There was no statistical difference between the two groups. BAI score after music therapy decreased in five patients in the music group and three patients in the control group. The BDI score decreased in six patients in the music group and four patients in the control group. The BDI score after music therapy decreased by average 2.3 points in the music group and increased by average 0.2 points in the control group. The change in BDI score was statistically significant in the music group (p=0.048), but not in the control group (Table 1). The BAI score after music therapy decreased by average 0.2 points in the music group, but did not change in the control group. The changes in the music and control group were not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of BDI and BAI before and after Music Therapy

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; MMSE, mini mental status examination; SD, standard deviation.

The decrease in BDI scores was statistically significant.

*p=0.048.

In the questionnaire for patients who received music therapy and their caregivers, the percentages of patients and caregivers who answered that there was a positive psychological change after music therapy were 77.8% and 66.7%, respectively. The percentages of patients and caregivers who answered that music therapy inspired motivation and actually helped rehabilitation treatment, and that they would actively recommend the music therapy to others were 66.7% and 55.6% respectively.

DISCUSSION

Standardized music therapy is currently being used as a new treatment for various diseases. It is known that it improves communication, linguistic development, emotional response, and behavioral adjustment in patients with autism,16 and improvement in the sound field, mood, and accentuation method was observed in patients with traumatic brain injury.17 Moreover, it has been reported that music therapy significantly decreased anxiety and blood pressure in patients who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate.18 According to Buffum, et al.,19 music therapy could reduce anxiety in patients who were about to undergo angiography. In Lee, et al.'s20 study, music therapy reduced anxiety in patients who received mechanical ventilation respiration.

We investigated the effects of music therapy on psychological status in stroke patients. Both the BAI and BDI scores decreased in stroke patients after music therapy, although only the decrease in BDI score was statistically significant. These findings are similar to previous studies showing that music therapy is effective for depression.21,22 According to Rudin, et al.,23 music therapy allowed patients to calmly undergo examinations by reducing stress and acting as painkiller during endoscopy. Furthermore, Koch, et al.24 insisted that music therapy in patients who are awake during surgery decreased the dose of anesthetics and sedatives required compared to patients who did not receive music therapy. As shown by these studies, music therapy decreases depression and anxiety and is being used effectively in various operations and treatments. In our study, distribution of BAI score in music therapy group represents minimal and mild level of anxiety, whether distribution of BDI score represents minimal to severe level of depression.25 This differences in distribution of BAI and BDI score could result in only subtle improvement in BAI.

One major advantage of music therapy is that it has a low possibility of side effects because it is noninvasive and does not use drugs. In a study on the mechanism of music therapy, Koelsch, et al.26 reported that unpleasant music showed activation of the limbic and paralimbic systems through functional MRI, which are known as the center of feelings, but pleasant music stimulated the inferior frontal gyrus and Rolandic operculum which reflect working memory. These results show that music therapy can intervene in feelings through the stimulation and non-stimulation of these structures, and we believe music can enhance functional abilities by inspiring motivation for rehabilitation treatment through the improvement of depression and anxiety.

Previous studies were just listening to music from records and had no standardized form or patient participating music therapy. However, our study used the 40-minute patient performing treatment method. This study is highly significant, because this is the first to intervene the mood of stroke patients using music therapy, which is still virtually unknown in clinical field.

Previous studies found significant differences in BDI scores between the control group and depression group.27 Similarly, significant differences in BAI scores were also observed between the control group and group of patients with anxiety or affective disorders,25 strongly suggesting that lower scores of BDI or BAI indicate lower incidences of depression or anxiety.

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, the number of patients included was small, and we didn't match the lesion site and severity of patients' disease and function. And the music therapy group was consisted of volunteers, therefore, the study was not blinded. Placebo effect cannot be ruled out in the music therapy group. Secondly, we didn't evaluate whether the treatment effect persisted even after music therapy stopped. Thirdly, the effect of medications such as antidepressants or sedatives was not considered.

According to Dafer, et al.,28 early diagnosis and successful intervention of post-stroke depression may improve clinical outcome and should be considered as a key to better stroke care. In this regard, our research is a leading study on the effects of music therapy on mood, which may result in functional improvement by giving emotional support for stroke patients hospitalized in a rehabilitation unit. In the questionnaire for patients and caregivers, many subjects answered that they were satisfied with music therapy and that it helped their rehabilitation. We found that further quantitative research into the effects of music therapy on rehabilitation treatment is necessary.

This study demonstrated that music therapy can reduce depressed mood or have positive effects on mood in post-stroke patients. Music therapy can inspire motivation for rehabilitation treatment and contribute to improvement in daily living functions and functional level. In the future, additional studies are needed on the effects of music therapy on ADL and functional level.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Standley JM. Music research in medical/dental treatment: meta-analysis and clinical applications. J Music Ther. 1986;23:56–122. doi: 10.1093/jmt/23.2.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peretti PO, Zweifel J. Affect of musical preference on anxiety as determined by physiological skin responses. Acta Psychiatr Belg. 1983;83:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson RG. Poststroke depression: prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:376–387. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House A, Dennis M, Warlow C, Hawton K, Molyneux A. The relationship between intellectual impairment and mood disorder in the first year after stroke. Psychol Med. 1990;20:805–814. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700036497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson RG, Lipsey JR, Rao K, Price TR. Two-year longitudinal study of post-stroke mood disorders: comparison of acute-onset with delayed-onset depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1238–1244. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paolucci S, Antonucci G, Pratesi L, Traballesi M, Grasso MG, Lubich S. Poststroke depression and its role in rehabilitation of inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:985–990. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wade DT, Legh-Smith J, Hewer RA. Depressed mood after stroke. A community study of its frequency. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:200–205. doi: 10.1192/bjp.151.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabaldón L, Fuentes B, Frank-García A, Díez-Tejedor E. Poststroke depression: importance of its detection and treatment. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(Suppl 1):181–188. doi: 10.1159/000107394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lökk J, Delbari A. Management of depression in elderly stroke patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:539–549. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo CS, Starkstein SE, Fedoroff JP, Price TR, Robinson RG. Generalized anxiety disorder after stroke. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:100–106. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aström M. Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke. 1996;27:270–275. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppävuori A, Pohjasvaara T, Vataja R, Kaste M, Erkinjuntti T. Generalized anxiety disorders three to four months after ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:257–264. doi: 10.1159/000071125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnellan C, Hickey A, Hevey D, O'Neill D. Effect of mood symptoms on recovery one year after stroke. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1288–1295. doi: 10.1002/gps.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradt J, Magee WL, Dileo C, Wheeler BL, McGilloway E. Music therapy for acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD006787. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006787.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wigram T, Gold C. Music therapy in the assessment and treatment of autistic spectrum disorder: clinical application and research evidence. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32:535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker F, Wigram T, Gold C. The effects of a song-singing programme on the affective speaking intonation of people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2005;19:519–528. doi: 10.1080/02699050400005150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yung PM, Chui-Kam S, French P, Chan TM. A controlled trial of music and pre-operative anxiety in Chinese men undergoing transurethral resection of the prostate. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:352–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buffum MD, Sasso C, Sands LP, Lanier E, Yellen M, Hayes A. A music intervention to reduce anxiety before vascular angiography procedures. J Vasc Nurs. 2006;24:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee OK, Chung YF, Chan MF, Chan WM. Music and its effect on the physiological responses and anxiety levels of patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a pilot study. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:609–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu WC, Lai HL. Effects of music on major depression in psychiatric inpatients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai YM. Effects of music listening on depressed women in Taiwan. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1999;20:229–246. doi: 10.1080/016128499248637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudin D, Kiss A, Wetz RV, Sottile VM. Music in the endoscopy suite: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Endoscopy. 2007;39:507–510. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koch ME, Kain ZN, Ayoub C, Rosenbaum SH. The sedative and analgesic sparing effect of music. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:300–306. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199808000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yook SP, Kim ZS. A clinical study on the Korean version of Beck Anxiety Inventory: comparative study of patient and non-patient. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1997;16:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koelsch S, Fritz T, V Cramon DY, Müller K, Friederici AD. Investigating emotion with music: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:239–250. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee YH, Song JY. A study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1991;10:98–113. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dafer RM, Rao M, Shareef A, Sharma A. Poststroke depression. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15:13–21. doi: 10.1310/tsr1501-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]