Abstract

Inflammation is associated with significant decreases in plasma HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and apoA-I levels. Endothelial lipase (EL) is known to be an important determinant of HDL-C in mice and in humans and is upregulated during inflammation. In this study, we investigated whether serum amyloid A (SAA), an HDL apolipoprotein highly induced during inflammation, alters the ability of EL to metabolize HDL. We determined that EL hydrolyzes SAA-enriched HDL in vitro without liberating lipid-free apoA-I. Coexpression of SAA and EL in mice by adenoviral vector produced a significantly greater reduction in HDL-C and apoA-I than a corresponding level of expression of either SAA or EL alone. The loss of HDL occurred without any evidence of HDL remodeling to smaller particles that would be expected to have more rapid turnover. Studies with primary hepatocytes demonstrated that coexpression of SAA and EL markedly impeded ABCA1-mediated lipidation of apoA-I to form nascent HDL. Our findings suggest that a reduction in nascent HDL formation may be partly responsible for reduced HDL-C during inflammation when both EL and SAA are known to be upregulated.

Keywords: ATP-binding cassette transporter A1, apolipoprotein A-I, cholesterol, inflammation

It has been recognized for decades that plasma concentrations of HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) are inversely related to the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (1). Accordingly, substantial interest is directed toward understanding the genetic and metabolic factors that influence HDL-C levels. It is well documented that endothelial lipase (EL) is an important determinant of HDL metabolism in both humans and rodents. In mice, overexpression of EL leads to significantly reduced plasma HDL-C (2–4) whereas decreased EL activity through either gene deletion (3, 5) or antibody inhibition (6) leads to increased HDL-C. In humans, plasma EL concentrations are inversely correlated with HDL-C levels (7) and rare missense mutations in EL are more common in humans with high HDL-C (8).

EL is a member of the triglyceride lipase gene family that also includes pancreatic lipase, lipoprotein lipase, and hepatic lipase (2). Unlike other members of this lipase family, EL exhibits relatively high phospholipase activity and low triglyceride lipase activity, and its favored substrate is HDL (9). Turnover studies in mice with adenoviral vector-mediated overexpression indicate that EL hydrolyzes HDL phospholipids in vivo and increases the fractional catabolic rate of HDL apolipoproteins in a dose-dependent manner (4). Based on studies carried out in vitro, EL phospholipase activity remodels HDL to smaller particles without dissociating lipid-poor apoA-I (10). This is in contrast to what occurs with hepatic lipase, where triglyceride hydrolysis of core lipids leads to shedding of lipid-poor apoA-I from destabilized HDL particles (11).

Evidence suggests that EL is increased in humans during inflammation, a condition associated with reduced HDL-C (12, 13). In cross-sectional studies, plasma markers of inflammation are strongly associated with plasma levels of EL (14, 15). EL concentrations are also associated with measures of the metabolic syndrome, which is considered a chronic low-grade inflammatory condition (7). Furthermore, low-dose endotoxin injection in healthy volunteers produces significantly increased levels of EL in the plasma 12 h after administration (15). Thus, an interesting question to address is how EL influences HDL metabolism during inflammation, when HDL undergoes substantial changes in lipid and apoliprotein composition (16). Most notably, HDL becomes enriched in serum amyloid A (SAA), a major acute phase reactant whose secretion from the liver may be increased more than 1,000-fold during inflammation. The vast majority of SAA in the plasma is found associated with HDL, where it can comprise the major apolipoprotein (17). Studies by Caiazza et al. (18) indicate that apolipoproteins on HDL may regulate EL-mediated remodeling, such that reconstituted HDLs (rHDL) containing both apoA-I and apoA-II are hydrolyzed more readily by EL compared with particles containing apoA-I only. Whether the presence of SAA on HDL can modulate HDL remodeling by EL has not been investigated. Previous studies from our laboratory showed that in the presence of SAA, perturbation of HDL core and surface lipid by scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) leads to generation of small, lipid-depleted apoA-I that is susceptible to catabolism (19). In this study, we carried out in vitro and in vivo studies to investigate whether the presence of SAA influences EL-mediated metabolism of HDL.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and used at 8-12 weeks of age. Mice were maintained on a 10 h light/14-h dark cycle and received standard mouse chow and water ad libidum. To induce an acute phase inflammatory response, mice were injected with 1 µg/g body weight lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, Cat # L2630). Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the approval of the Lexington Veterans Affairs Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Adenoviral vectors

SAA was expressed alone or in combination with EL or SR-BI in livers of mice using adenoviral vector-mediated gene transfer. The indicated dose of AdSAA, a vector encoding mouse CE/J SAA isotype (20), AdSR-BI, a vector encoding mouse SR-BI (21) or AdEL, a vector encoding human endothelial lipase [generously provided by Dr. Daniel Rader (9)] was administered via tail vein injection in 100 μl PBS. For estimates of EL expression 72 h after adenoviral vector infusion, mice were injected i.p. with 2.5 U heparin in 100 μl PBS 30 min prior to plasma collection. In the case of the AdSAA + AdSR-BI experiments, the dose of AdSR-BI increased hepatic SR-BI expression ∼3-fold, which resulted in a ∼50% decline in HDL levels, whereas hepatic SAA was increased ∼8-fold without impacting HDL levels when expressed by itself (19).

HDL isolation and hydrolysis by EL in vitro

HDL (d = 1.063 to 1.21 g/ml) was isolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation from plasma of untreated C57BL/6 mice or mice 24 h after injection with LPS (17). HDL was then dialyzed against 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.01% EDTA, filter sterilized, and stored at 4°C under argon gas. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (22). AdEL was used to express recombinant EL (rEL) in COS-7 cells according to published methods (9). For in vitro hydrolysis, HDL (0.8 mM final phospholipid concentration, ∼40 μg protein) was incubated at 37°C for 24 h in TBS supplemented with the indicated amount of culture supernatant containing human rEL, 10 mg/ml fatty-acid free BSA, and 4 mM Ca2+ (total volume, 50 μl). The extent of HDL hydrolysis was assessed by measuring the amount of FFA released into the reaction mixture by colorimetric assay (Wako).

Primary hepatocyte cultures

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice 24 h after infusion of AdNull, AdEL (1 × 1010 particles), AdSAA (5 × 1010 particles), or AdEL plus AdSAA. In all cases, Adnull was added to deliver 6 × 1010 total particles per mouse. A two-step perfusion method was utilized for isolation of hepatocytes (23). Briefly, the liver was first perfused with Ca+2/Mg+2-free HBSS containing 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES, and 0.3 mM EDTA and then with HBSS containing 0.05% collagenase type IV (Sigma), 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES. Hepatocytes were washed by repeated low speed centrifugation (50 g for 2 min), and viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Cells were plated onto 12-well collagen-coated plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/per well and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 in Williams’ Medium E (GIBCO) containing 10% FBS (GIBCO), 2% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (GIBCO). Cells were treated with the Liver X Receptor (LXR) agonist T0901317 (5 µM; Cayman Chemical) in serum-free medium containing 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA for 8 h to induce the expression of ABCA1 and then incubated with 15 µg/ml lipid-free human apoA-I (Meridian Life Science, Inc.) in medium containing 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA. Cell lysates and culture supernatants were harvested after 18 h incubation for analysis.

Plasma HDL-C quantifications

Plasma HDL-C was measured using a commercially available kit (Wako) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblot analysis

Plasma samples from mice were separated by 4-20% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue or transferred to PVDF membranes (100 min at 100 V, 4°C) and immunoblotted with anti-mouse apoA-I (Biodesign International) or rabbit anti-human EL (Cayman Chemical). Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (GE Healthcare) and quantified by densitometry. For other studies, plasma or cell culture supernatants were subjected to nondenaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (GGE). Electrophoresis was carried out in 4-20% polyacrylamide gels for 3.5 h at 200 V, 4°C and the samples were then transferred to PVDF membranes and immunoblotted using anti-mouse apoA-I or anti-human apoA-I (Calbiochem) as indicated in legends to figures. For assessment of ABCA1 expression in primary hepatocytes, total cell lysates (10 µg) were separated on a 4-20% polyacrylamide gradient gel, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and immunoblotted with anti-ABCA1 (ABCAM ab7360).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses to compare differences between plasma HDL levels at selected intervals after viral vector administration were carried out using two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest.

RESULTS

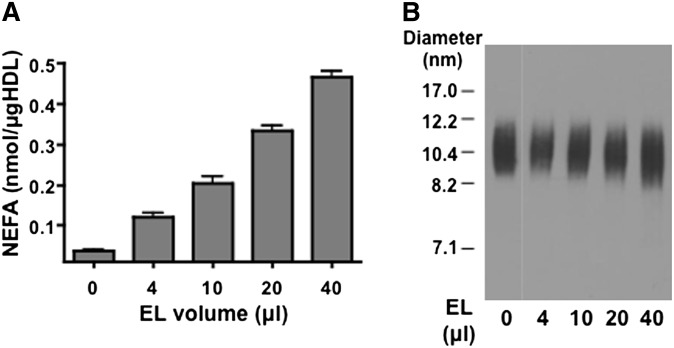

EL remodeling of normal and SAA-containing mouse HDL in vitro

Previous studies demonstrated that EL hydrolyzes rHDL or HDL isolated from human plasma without generating lipid-poor apoA-I (10). In this study, we assessed whether EL remodels mouse HDL in a similar manner. Incubations with EL resulted in dose-dependent hydrolysis of normal mouse HDL as indicated by an increase in the release of FFAs (Fig. 1A). At maximal hydrolysis, ∼53% of the HDL phospholipids was hydrolyzed. Analysis by nondenaturing GGE indicated that lipid-poor apoA-I (which migrates faster than the 7.1 nm standard) is not released from mouse HDL, even when >50% of phospholipids are hydrolyzed (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

EL remodeling of normal mouse HDL in vitro does not liberate lipid-poor apoA-I. C57BL/6 mouse HDL was incubated for 24 h with the indicated amount of conditioned media from EL-expressing COS-7 cells. A: The amount of FFA released in each of the reaction mixtures was measured; values shown are the means of triplicate determinations (± SEM). B: Aliquots from hydrolysis mixes corresponding to 1 μg HDL protein were separated by nondenaturing GGE and immunoblotted with anti-mouse apoA-I. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments using different mouse HDL preparations.

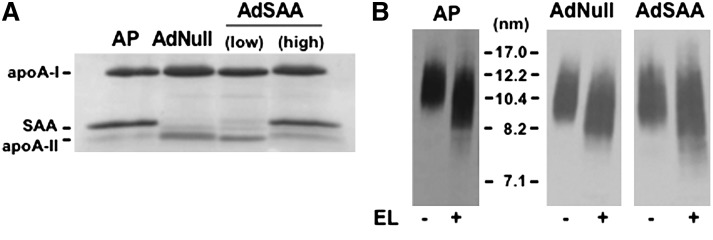

Studies by Caiazza et al. (18) demonstrated that rHDLs containing both apoA-I and apoA-II are better substrates for EL hydrolysis compared with rHDLs containing apoA-I only, suggesting that apolipoproteins modulate EL-mediated HDL remodeling. Thus, it was of interest to determine whether the presence of SAA on HDL alters the ability of EL to remodel the particle to liberate apoA-I. To prepare HDLs for these studies, mice were injected with either LPS to induce an acute phase response, or an adenoviral vector (1.5 × 1011 particles) that expresses high levels of SAA in the absence of inflammation (AdSAA). Analysis by SDS-PAGE indicated that HDL isolated from LPS or AdSAA-injected mice were highly enriched in SAA compared with mice infused with a control adenoviral vector (Fig. 2A). The HDL preparations were incubated with EL and then separated by nondenaturing GGE. Similar to what occurs with human and normal mouse HDL, EL hydrolysis of SAA-containing HDL does not result in the dissociation of lipid-poor apoA-I (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

EL remodeling of acute phase mouse HDL in vitro does not liberate lipid-poor apoA-I. HDL was isolated from plasma of mice 24 h after injection of LPS (AP) or 72 h after infusion of a control adenovirus (Adnull; 1.5 × 1011 particles) or a low dose (2.5 × 1010 particles) or high dose (1.5 × 1011 particles) of AdSAA. A: Aliquots corresponding to 3 μg HDL protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. B: AP-HDL and HDL from mice infused with Adnull or high dose AdSAA were incubated for 24 h with or without 40 μl EL as indicated and then separated by nondenaturing GGE and immunoblotted using anti-mouse apoA-I.

Effect of SAA on EL-mediated HDL metabolism in vivo

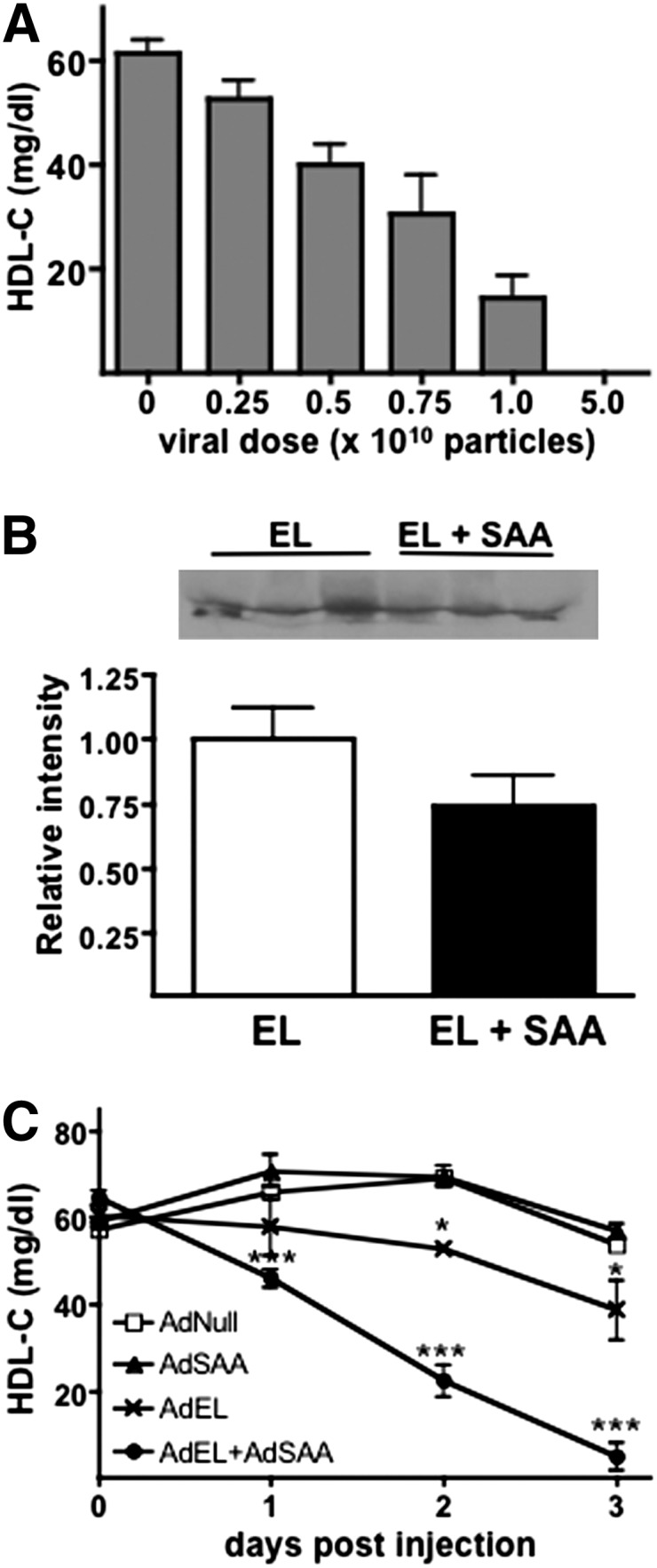

We next investigated whether SAA alters EL-mediated metabolism of HDL in vivo. As reported by Maugeais et al. (4), overexpression of EL in mice by adenoviral vector reduces plasma HDL-C in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). For our studies, we selected a dose of AdEL (0.5 × 1010 particles) that resulted in a reproducible 30–40% reduction in HDL-C 3 days after viral vector injection. We also selected a dose of AdSAA (2.5 × 1010 particles) that only modestly enriched HDL particles with SAA (Fig. 2A). C57BL/6 mice were injected with mixtures of AdEL, AdSAA, and AdNull to provide a total viral dose of 3 × 1010 particles/mouse. Infusion of AdSAA along with AdEL resulted in a modest but not statistically significant reduction in the amount of EL in postheparin plasma compared with AdEL alone (Fig. 3B). Plasma HDL-C concentrations were determined at selected intervals up to 72 h after injection, when adenoviral vector gene expression was maximal. Whereas AdEL resulted in the expected ∼35% reduction in HDL-C 72 h after injection, infusion of AdNull or AdSAA had no effect on HDL-C levels at any time point during the course of the experiment (Fig. 3C). In contrast, HDL-C was reduced ∼90% when AdSAA and AdEL were administered together, despite comparable levels of EL in plasma. This result suggests a synergistic effect of SAA and EL on HDL metabolism.

Fig. 3.

Coexpression of SAA with EL markedly reduces HDL-C in vivo. A: Plasma HDL-C concentrations were determined 72 h after administration of the indicated dose of AdEL. Values are the mean (± SEM) of at least four mouse plasma samples assayed in duplicate. B: Postheparin plasma was collected from mice 72 h after injection of AdEL (0.5 × 1010 particles) or AdEL + AdSAA (2.5 × 1010 particles) as described in Methods and immunoblotted using anti-human EL. Upper panel: Representative immunoblots of three individual mouse plasmas; Lower panel: Quantitative results from densitometric scanning (n = 6). C: Mice were injected with a total of 3 × 1010 adenovirus particles, consisting of a mixture of Adnull, AdEL (0.5 × 1010 particles), and/or AdSAA (2.5 × 1010 particles) and HDL-C concentrations were determined at the indicated time after injection. Values are the mean (± SEM) of four mouse plasma samples assayed in duplicate. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 and *** p < 0.001 compared with Adnull-treated mice.

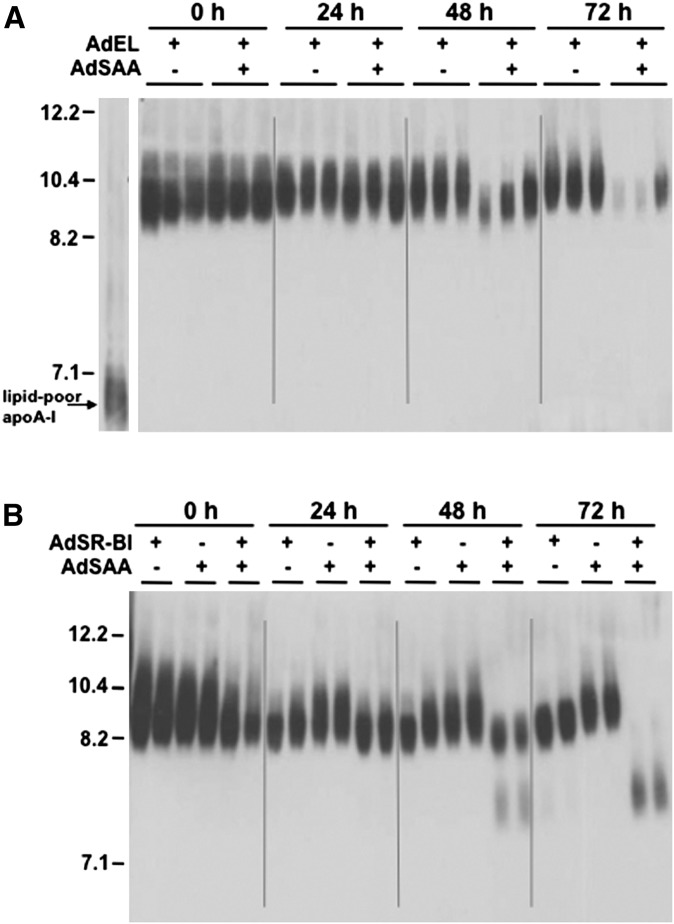

Effect of SAA on EL-mediated HDL remodeling in vivo

To investigate whether the increased EL-mediated HDL metabolism in SAA-expressing mice was accompanied by enhanced HDL remodeling, plasma from AdEL and AdEL + AdSAA-treated mice were fractionated by nondenaturing GGE and immunoblotted for apoA-I. The reduction in HDL-C levels that occurred with EL and SAA coexpression was accompanied by a marked loss of apoA-I protein at 48 and 72 h (Fig. 4A). Indeed, quantification of apoA-I protein by densitometry revealed that plasma concentrations of apoA-I 72 h after AdEL + AdSAA infusion were 84% lower compared with plasma of mice expressing EL alone (not shown). Interestingly, there was no evidence that surface perturbation of HDL by EL in the presence of SAA resulted in the formation of small, lipid-depleted particles (Fig. 4A). These findings contrast to what we have previously shown to occur with HDL core remodeling by SR-BI (19) and repeat here for illustrative purposes (Fig. 4B). In this case, coexpression of SAA and SR-BI by adenoviral vector leads to enhanced reduction in HDL-C compared with expression of SR-BI or SAA alone (19) (data not shown), and this effect is associated with enhanced generation of small, lipid depleted apoA-I that is susceptible to catabolism (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

The reduction of plasma apoA-I in mice infused with AdEL + AdSAA is not accompanied by the appearance of lipid poor HDL. A: Mice were injected with a total of 3 × 1010 adenovirus particles, consisting of a mixture of Adnull, AdEL (0.5 × 1010 particles), and AdSAA (2.5 × 1010 particles), as indicated. B: Mice were injected with a total of 1.5 × 1011 adenovirus particles, consisting of a mixture of Adnull, AdSR-BI (0.5 × 1011 particles), and AdSAA (1 × 1011 particles), as indicated. A, B: At the indicated time, plasma samples (3 μl) were separated by nondenaturing GGE and immunoblotted using anti-mouse apoA-I.

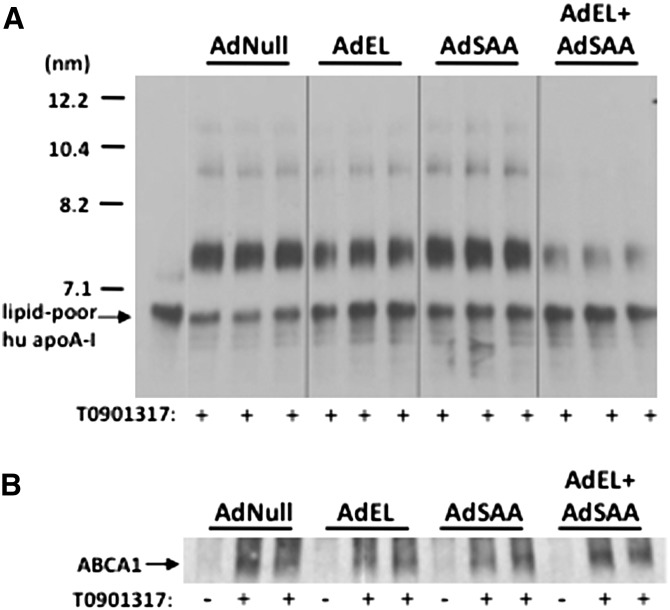

Impact of EL and SAA on HDL formation

The marked reduction in apoA-I in AdEL + AdSAA-treated mice prompted us to consider the possibility that HDL biogenesis may be altered when EL and SAA were coexpressed. The initiating step in HDL assembly involves lipidation of apoA-I to form nascent HDL particles. Studies in gene-targeted mice indicate that the major site of lipidation is the liver, where ABCA1 mediates the efflux of cholesterol and phospholipid from hepatocytes to lipid-free apoA-I (24). To examine the effect of concomitant EL and SAA expression on HDL biogenesis, primary hepatocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice 24 h after adenoviral vector infusions, and the impact of EL and/or SAA expression on the ability of hepatocytes to convert lipid-poor apoA-I to nascent HDL was assessed (Fig. 5). As shown previously, the interaction of lipid-free apoA-I with hepatocytes leads to the formation of multiple discretely sized particles ranging from ∼7.4 to 20 nm in size (25). These nascent HDLs are known to differ in apoA-I, phospholipid, and cholesterol content (26, 27). Interestingly, compared with hepatocytes from AdNull-treated mice, nascent HDL formation by hepatocytes expressing EL alone was slightly reduced, indicating that EL may alter HDL biogenesis as well as the metabolism of mature HDL. Expression of SAA had no apparent effect on apoA-I lipidation. However, concomitant expression of EL and SAA resulted in a marked reduction in the conversion of lipid-poor apoA-I to nascent HDL. This difference in apoA-I lipidation was not due to differences in ABCA1 expression (Fig. 5B). Taken together, our data indicate that EL and SAA act synergistically to interfere with HDL formation.

Fig. 5.

Lipidation of apoA-I is reduced when EL and SAA are coexpressed in hepatoctyes. Mice were injected with a total of 6 × 1010 particles per mouse, consisting of a mixture of AdNull, AdEL (1 × 1010 particles), AdSAA (5 × 1010 particles), or AdEL + AdSAA as indicated. Primary hepatocyte cultures were prepared 24 h after infusion, treated with the LXR agonist T0901317 for 8 h to upregulate ABCA1, and then incubated for 18 h with 15 μg/ml lipid-free apoA-I. A: Culture supernatants were separated by nondenaturing GGE and immunoblotted using anti-human apoA-I. Lipid-free apoA-I was included on the gel for comparison. B: Lysates of cells prepared before or after T0901317 treatment (10 µg cell protein) were separated on a 4-20% polyacrylamide gradient gel and immunoblotted using anti-ABCA1.

DISCUSSION

HDL comprises a polydisperse population of lipoproteins that includes larger spherical particles as well as smaller lipid-poor discoidal HDL. The synthesis of new HDL particles occurs primarily in the liver, where apoA-I is secreted in a lipid-poor/lipid-free form. The addition of phospholipids and cholesterol to apoA-I occurs extracellularly through the action of the lipid transporter ABCA1. The resulting disc-shaped particles, conventionally designated preβ-HDL, are then converted to mature spherical HDL. In plasma, these particles are in a dynamic equilibrium that involves active and continuous remodeling mediated by a number of cellular receptors, lipid transport proteins, and modifying enzymes. It is well documented that EL plays a major role in HDL metabolism through its capacity to remodel circulating HDL particles and hence promote their catabolism (3, 4, 28). In this study, we show for the first time that EL may also modulate HDL metabolism by reducing the extent to which apoA-I is lipidated in the liver, an effect that is amplified when hepatic cells secrete SAA. The combined effect of SAA and EL to impede apoA-I lipidation may partly explain the reduction in HDL-C that is known to occur during inflammation, when both EL and SAA are induced.

The effect of EL on HDL surface remodeling has been extensively investigated by Rye and colleagues (10, 18). Kinetic studies in vitro indicated that the Vmax of phospholipid hydrolysis is significantly greater for rHDLs containing both apoA-I and apoA-II compared with rHDL containing only apoA-I (18), whereas rHDL containing only apoA-II undergoes minimal EL hydrolysis (10, 18). Given that rHDL preparations used in these studies were of similar size and lipid composition, these findings strongly suggested that apolipoproteins on HDL are a major determinant of EL hydrolysis. On the other hand, Broedl et al. (29) reported that adenovirus expression of EL was less effective in altering HDL metabolism in apoA-I/apoA-II double transgenic mice compared with apoA-I single transgenic mice, indicating that apoA-II reduces the ability of EL to alter HDL metabolism in vivo. In the current study, we demonstrated that enrichment with SAA has no discernible effect on the ability of EL to remodel mouse HDL in vitro. We also provide evidence that SAA amplifies the effect of EL on HDL metabolism in vivo, but through a mechanism that appears to be independent of HDL remodeling in the circulation.

Based on in vitro studies using rHDLs, EL-mediated phospholipid hydrolysis leads to the formation of smaller HDL particles without dissociating either lipid-poor apoA-I or apoA-II (10). Thus, the impact of EL on HDL remodeling appears to be analogous to what occurs with phospholipase A2, where surface hydrolysis leads to the formation of small HDL particles without releasing apoA-I (30). In contrast, the triglyceride lipase activity of hepatic lipase remodels HDL to form smaller particles and generate lipid-poor apoA-I (11). In the current study, we found no evidence that enrichment with SAA promotes the dissociation of lipid-poor apolipoproteins from EL-hydrolyzed HDL either in vitro or in vivo. Thus, it does not appear that SAA impacts EL-mediated intravascular HDL remodeling. Nevertheless, SAA significantly enhanced the ability of EL to reduce HDL-C and apoA-I levels in vivo. Our data indicate this synergism may be attributed to the combined effect of SAA and EL to interfere with the conversion of lipid-poor apoA-I to nascent HDL at the surface of the liver, thereby reducing the production rate of mature HDL. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Maugeais et al., (4) who measured the plasma clearance rate of HDL in mice with adenoviral vector-mediated EL overexpression. Although AdEL significantly increased the fractional catabolic rate of mature HDL, the increase in the rate of clearance clearly could not account for the substantial decrease in plasma apoA-I levels that was observed in AdEL-infused mice. This points to an alteration in the rate of HDL production as an important factor contributing to the effect of EL in lowering HDL levels. The authors speculated that EL hydrolyzes nascent HDL phospholipids and consequently reduces the maturation of lipid-poor apoA-I to spherical HDL. Our findings suggest that the entry of nascent HDL into the mature HDL pool may be further impeded during inflammation, when both EL and SAA are present.

The mechanism by which SAA and EL interact to disrupt nascent HDL formation is unclear. ApoA-I lipidation by ABCA1 is known to occur through a multi-step process that is initiated by the high affinity binding of apoA-I to ABCA1 (31). The consequent activation and stabilization of ABCA1 leads to the formation of high capacity binding sites on the plasma membrane where lipid-poor apoA-I can effectively solubilize membrane phospholipids and cholesterol to form nascent HDLs (32, 33). Although both apoA-I binding sites are dependent on ABCA1, the high capacity binding site does not involve a direct interaction between apoA-I and ABCA1. Thus, factors that interfere with ABCA1 activation or the formation of the high capacity binding site would be expected to disrupt apoA-I-mediated cholesterol and phospholipid efflux and HDL biogenesis. There is evidence to suggest that both SAA and EL modulate ABCA1-dependent efflux, although both factors are in general thought to promote the removal of cellular cholesterol by ABCA1 (34–36). However, earlier studies did not investigate whether enhanced cholesterol efflux was accompanied by increased apoA-I lipidation, a key event in HDL biogenesis.

In summary, we report the novel finding that coexpression of SAA and EL by adenoviral vector-mediated gene transfer reduces HDL-C in mice to an extent that is significantly more pronounced than when EL is expressed alone. Notably, the cooperative effect of SAA and EL was not accompanied by the appearance of small, lipid-depleted HDLs in the plasma, as would be expected to occur if HDL was undergoing enhanced intravascular remodeling. Our data indicate that apoA-I lipidation by mouse hepatocytes is markedly reduced when EL and SAA are coexpressed. Taken together, our findings suggest that a reduction in nascent HDL formation may be partly responsible for reduced HDL-C during inflammation, when both EL and SAA are known to be upregulated. Current strategies for raising HDL-C to lower cardiovascular disease risk include increasing HDL production (37, 38). Our finding that inflammatory factors may serve to negatively impact nascent HDL formation may be important to consider in order to maximize the success of such strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vicky Noffsinger for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01HL086670. The studies were supported with resources and the use of facilities provided by the Lexington, KY Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other granting agencies.

Abbreviations:

- EL

- endothelial lipase

- GGE

- gradient gel electrophoresis

- HDL-C

- HDL cholesterol

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- rEL

- recombinant EL

- rHDL

- reconstituted HDL

- SAA

- serum amyloid A

- SR-BI

- scavenger receptor class B type I

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon D. J., Rifkind B. M. 1989. High-density lipoprotein–the clinical implications of recent studies. N. Engl. J. Med. 321: 1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaye M., Lynch K. J., Krawiec J., Marchadier D., Maugeais C., Doan K., South V., Amin D., Perrone M., Rader D. J. 1999. A novel endothelial-derived lipase that modulates HDL metabolism. Nat. Genet. 21: 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishida T., Choi S., Kundu R. K., Hirata K., Rubin E. M., Cooper A. D., Quertermous T. 2003. Endothelial lipase is a major determinant of HDL level. J. Clin. Invest. 111: 347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maugeais C., Tietge U. J., Broedl U. C., Marchadier D., Cain W., McCoy M. G., Lund-Katz S., Glick J. M., Rader D. J. 2003. Dose-dependent acceleration of high-density lipoprotein catabolism by endothelial lipase. Circulation. 108: 2121–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma K., Cilingiroglu M., Otvos J. D., Ballantyne C. M., Marian A. J., Chan L. 2003. Endothelial lipase is a major genetic determinant for high-density lipoprotein concentration, structure, and metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 2748–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin W., Millar J. S., Broedl U., Glick J. M., Rader D. J. 2003. Inhibition of endothelial lipase causes increased HDL cholesterol levels in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 111: 357–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badellino K. O., Wolfe M. L., Reilly M. P., Rader D. J. 2006. Endothelial lipase concentrations are increased in metabolic syndrome and associated with coronary atherosclerosis. PLoS Med. 3: e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.deLemos A. S., Wolfe M. L., Long C. J., Sivapackianathan R., Rader D. J. 2002. Identification of genetic variants in endothelial lipase in persons with elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Circulation. 106: 1321–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCoy M. G., Sun G. S., Marchadier D., Maugeais C., Glick J. M., Rader D. J. 2002. Characterization of the lipolytic activity of endothelial lipase. J. Lipid Res. 43: 921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahangiri A., Rader D. J., Marchadier D., Curtiss L. K., Bonnet D. J., Rye K. A. 2005. Evidence that endothelial lipase remodels high density lipoproteins without mediating the dissociation of apolipoprotein A-I. J. Lipid Res. 46: 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clay M. A., Newnham H. H., Barter P. J. 1991. Hepatic lipase promotes a loss of apolipoprotein A-I from triglyceride-enriched human high density lipoproteins during incubation in vitro. Arterioscler. Thromb. 11: 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cabana V. G., Siegel J. N., Sabesin S. M. 1989. Effects of the acute phase response on the concentration and density distribution of plasma lipids and apolipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 30: 39–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardardóttir I., Grunfeld C., Feingold K. R. 1994. Effects of endotoxin and cytokines on lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 5: 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paradis M. E., Badellino K. O., Rader D. J., Deshaies Y., Couture P., Archer W. R., Bergeron N., Lamarche B. 2006. Endothelial lipase is associated with inflammation in humans. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2808–2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badellino K. O., Wolfe M. L., Reilly M. P., Rader D. J. 2008. Endothelial lipase is increased in vivo by inflammation in humans. Circulation. 117: 678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khovidhunkit W., Kim M. S., Memon R. A., Shigenaga J. K., Moser A. H., Feingold K. R., Grunfeld C. 2004. Effects of infection and inflammation on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism: mechanisms and consequences to the host. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1169–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coetzee G. A., Strachan A. F., van der Westhuyzen D. R., Hoppe H. C., Jeenah M. A., de Beer F. C. 1986. Serum amyloid A-containing human high density lipoprotein 3: density, size and apolipoprotein composition. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 9644–9651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caiazza D., Jahangiri A., Rader D. J., Marchadier D., Rye K. A. 2004. Apolipoproteins regulate the kinetics of endothelial lipase-mediated hydrolysis of phospholipids in reconstituted high-density lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 43: 11898–11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Beer M. C., Webb N. R., Whitaker N. L., Wroblewski J. M., Jahangiri A., van der Westhuyzen D. R., de Beer F. C. 2009. SR-BI selective lipid uptake: subsequent metabolism of acute phase HDL. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 1298–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb N. R., de Beer M. C., van der Westhuyzen D. R., Kindy M. S., Banka C. L., Tsukamoto K., Rader D. L., de Beer F. C. 1997. Adenoviral vector-mediated overexpression of serum amyloid A in apoA-I-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 38: 1583–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb N. R., Connell P. M., Graf G. A., Smart E. J., de Villiers W. J., de Beer F. C., van der Westhuyzen D. R. 1998. SR-BII, an isoform of the scavenger receptor BI containing an alternate cytoplasmic tail, mediates lipid transfer between high density lipoprotein and cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 15241–15248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall B. J. 1951. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagant. J. Biol. Chem. 193: 265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seglen P. O. 1976. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 13: 29–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timmins J. M., Lee J. Y., Boudyguina E., Kluckman K. D., Brunham L. R., Mulya A., Gebre A. K., Coutinho J. M., Colvin P. L., Smith T. L., et al. 2005. Targeted inactivation of hepatic Abca1 causes profound hypoalphalipoproteinemia and kidney hypercatabolism of apoA-I. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 1333–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krimbou L., Hajj Hassan H., Blain S., Rashid S., Denis M., Marcil M., Genest J. 2005. Biogenesis and speciation of nascent apoA-I-containing particles in various cell lines. J. Lipid Res. 46: 1668–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duong P. T., Collins H. L., Nickel M., Lund-Katz S., Rothblat G. H., Phillips M. C. 2006. Characterization of nascent HDL particles and microparticles formed by ABCA1-mediated efflux of cellular lipids to apoA-I. J. Lipid Res. 47: 832–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulya A., Lee J. Y., Gebre A. K., Thomas M. J., Colvin P. L., Parks J. S. 2007. Minimal lipidation of pre-beta HDL by ABCA1 results in reduced ability to interact with ABCA1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1828–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broedl U. C., Jin W., Rader D. J. 2004. Endothelial lipase: a modulator of lipoprotein metabolism upregulated by inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 14: 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broedl U. C., Jin W., Fuki I. V., Millar J. S., Rader D. J. 2006. Endothelial lipase is less effective at influencing HDL metabolism in vivo in mice expressing apoA-II. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2191–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rye K. A., Duong M. N. 2000. Influence of phospholipid depletion on the size, structure, and remodeling of reconstituted high density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 41: 1640–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vedhachalam C., Duong P. T., Nickel M., Nguyen D., Dhanasekaran P., Saito H., Rothblat G. H., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C. 2007. Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 25123–25130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vedhachalam C., Ghering A. B., Davidson W. S., Lund-Katz S., Rothblat G. H., Phillips M. C. 2007. ABCA1-induced cell surface binding sites for ApoA-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan H. H., Denis M., Lee D. Y., Iatan I., Nyholt D., Ruel I., Krimbou L., Genest J. 2007. Identification of an ABCA1-dependent phospholipid-rich plasma membrane apolipoprotein A-I binding site for nascent HDL formation: implications for current models of HDL biogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 48: 2428–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stonik J. A., Remaley A. T., Demosky S. J., Neufeld E. B., Bocharov A., Brewer H. B. 2004. Serum amyloid A promotes ABCA1-dependent and ABCA1-independent lipid efflux from cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321: 936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yancey P. G., Kawashiri M. A., Moore R., Glick J. M., Williams D. L., Connelly M. A., Rader D. J., Rothblat G. H. 2004. In vivo modulation of HDL phospholipid has opposing effects on SR-BI- and ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 45: 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu G., Hill J. S. 2009. Endothelial lipase promotes apolipoprotein AI-mediated cholesterol efflux in THP-1 macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duffy D., Rader D. J. 2009. Update on strategies to increase HDL quantity and function. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 6: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey D., Jahagirdar R., Gordon A., Hafiane A., Campbell S., Chatur S., Wagner G. S., Hansen H. C., Chiacchia F. S., Johansson J., et al. 2010. RVX-208: a small molecule that increases apolipoprotein A-I and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in vitro and in vivo. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55: 2580–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]