Abstract

Alterations in the intestinal microbiota have been suggested as an etiological factor in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This study used a molecular fingerprinting technique to compare the composition and biodiversity of the microbiota within fecal and mucosal niches between patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) and healthy controls. Terminal-restriction fragment (T-RF) length polymorphism (T-RFLP) fingerprinting of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was used to perform microbial community composition analyses on fecal and mucosal samples from patients with D-IBS (n = 16) and healthy controls (n = 21). Molecular fingerprinting of the microbiota from fecal and colonic mucosal samples revealed differences in the contribution of T-RFs to the microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. Further analysis revealed a significantly lower (1.2-fold) biodiversity of microbes within fecal samples from D-IBS patients than healthy controls (P = 0.008). No difference in biodiversity in mucosal samples was detected between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. Multivariate analysis of T-RFLP profiles demonstrated distinct microbial communities between luminal and mucosal niches in all samples. Our findings of compositional differences in the luminal- and mucosal-associated microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls and diminished microbial biodiversity in D-IBS fecal samples further support the hypothesis that alterations in the intestinal microbiota may have an etiological role in the pathogenesis of D-IBS and suggest that luminal and mucosal niches need to be investigated.

Keywords: terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism, microbial biodiversity

irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most prevalent functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, affecting 10–20% of adults and adolescents (20). IBS can present as diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS), constipation-predominant IBS, or mixed-bowel-habit IBS. These disorders are associated with a significantly reduced quality of life (17), psychological comorbidities (21), and a considerable economic burden (44). The lack of understanding of the factors associated with the pathogenesis of this complex group of disorders has resulted in limited effective treatment options for IBS patients. Recent studies have implicated new etiological factors in the pathogenesis of IBS, including alterations in the normal intestinal microbiota, genetic predeterminants, pathogenic bacterial infection, food sensitivity/allergy, altered enteric immune function, and intestinal inflammation (2, 30, 34).

The intestinal microbiota has been demonstrated to be important for normal GI motor and sensory functions (5, 14, 18, 34, 35), and alterations in the intestinal microbiota have been suggested as a possible etiological factor in the development of functional GI disorders, including IBS (34). Indeed, attempts to alter the composition of the intestinal microbiota using antibiotics, probiotics, or prebiotics have resulted in reduced IBS symptoms (8, 13, 27, 31–33, 35, 39, 43). Several studies have characterized a dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota in patients with IBS. However, there is no consensus among these studies regarding the specific compositional changes of the intestinal microbiota associated with these disorders (4, 6, 9, 15, 16, 22, 23, 25, 26, 45). Identification of specific alterations in the intestinal bacterial groups that are associated with IBS symptoms is complicated by the heterogeneity of the disorders and the diversity of the intestinal microbiota (19). In addition, it is unclear whether symptoms of IBS are associated with compositional variation of microbial groups in the luminal and/or mucosal niches (49). Therefore, the possible association between IBS and the intestinal microbiota must be investigated in clinically relevant, well-defined subgroups of patients, and luminal and mucosal niches must be analyzed using techniques that explore the composition and diversity of these complex microbial communities. The present study used the molecular fingerprinting technique terminal-restriction fragment (T-RF) length polymorphism (T-RFLP) (7) to characterize and compare the microbiota in fecal and colonic mucosal samples obtained from a subgroup of D-IBS patients and healthy controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

We studied 16 patients that met the Rome III criteria for D-IBS and 21 healthy controls. Subjects were recruited from the general population of Chapel Hill, NC, with advertising and from the University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals outpatient clinics.

Inclusion criteria included subjects ≥18 yr of age and of any sex, race, or ethnicity. Healthy controls had no recurring GI symptoms. Subjects with a history of GI tract surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy or a history of inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, lactose malabsorption, or any other diagnosis that could explain chronic or recurring bowel symptoms were excluded from the study. In addition, individuals were excluded if they had a history of treatment with antibiotics or anti-inflammatory agents, including aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (or steroids), or if they had intentionally consumed probiotics 2 mo prior to the study.

All subjects were evaluated by a physician to exclude an alternative diagnosis to IBS. The study was approved by the UNC Internal Review Board, and all subjects provided written consent prior to participation in the study.

Sample collection and preparation.

Fresh stool samples were collected from all 37 subjects on site during a single study visit at UNC. Each fecal sample was immediately transferred on ice to the laboratory, where it was homogenized, divided into aliquots, and stored at −80°C for future DNA extraction and molecular microbiological analysis.

Colonic mucosal biopsies (n = 8 per patient) were collected from each subject at a single study visit during an unsedated flexible sigmoidoscopy. To avoid possible effects of colonic preparation on the composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota, all biopsies were collected from unprepared colons (i.e., subjects did not undergo a bowel cleansing prior to the procedure). Cold forceps were used to take mucosal biopsy samples from the rectosigmoid colon. Taking biopsy samples from the rectosigmoid junction permits consistent collection of samples representative of the distal colon from all subjects and minimizes the discomfort associated with the procedure. Once removed from the colon, each biopsy sample was washed in 1 ml of sterile PBS to remove fecal material. The biopsy samples were then weighed, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for further DNA extraction and molecular microbiological analysis.

Extraction of DNA.

Bacterial DNA was extracted from one fecal and one mucosal sample from each of the subjects. DNA was isolated from 18 (7 D-IBS patients and 11 healthy controls) fecal and mucosal samples using a phenol-chloroform extraction method combined with physical disruption of bacterial cells and a DNA clean-up kit (DNeasy blood and tissue extraction kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Briefly, a 100-mg sample of frozen feces or a mucosal biopsy was suspended in 750 μl of sterile bacterial lysis buffer [200 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 20 mM EDTA, and 20 mg/ml lysozyme] and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Then 40 μl of proteinase K (20 mg/ml) and 85 μl of 10% SDS were added to the mixture. After 30 min of incubation at 65°C, 300 mg of 0.1-mm zirconium beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) were added, and the mixture was homogenized in a bead beater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for 2 min. The homogenized mixture was cooled on ice and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5-ml microfuge tube, and fecal DNA was further extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and then by chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). After extraction, the supernatant was precipitated by absolute ethanol at −20°C for 1 h. The precipitated DNA was suspended in DNase-free H2O and then cleaned using the DNeasy blood and tissue extraction kit (see above) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Additional fecal and mucosal DNA from 19 subjects (9 D-IBS patients and 10 healthy controls) was obtained from samples collected in a previous study (6). The study population, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and sample collection and handling procedures were identical in both studies.

T-RFLP PCR.

A complex mixture of bacterial 16S rRNA genes was amplified by PCR from each intestinal DNA sample using fluorescently labeled universal primers [carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ (forward primer 8F) and hexachlorocarboxyfluorescein (HEX)-labeled 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′ (reverse primer 1492R)], as previously described (10, 40). PCR products were purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit. PCR products of all fecal and mucosal samples were then digested with Hha I to generate T-RFs of varying sizes. All fecal samples were also digested separately with Hae III or Msp I (mucosal samples were not digested with Hae III or Msp I because of a limited supply of DNA). As a result of polymorphisms in the variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, T-RF size corresponds to different bacterial groups. T-RFs were separated by capillary electrophoresis on a genetic analyzer (model 3100, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems) was used to determine the size (terminal fragment length in base pairs), height (fluorescence intensity), and abundance (peak width × height) of each T-RF. To attribute specific bacterial groups to T-RFs, we compared the fingerprints generated from each sample with a database containing T-RF data from known and unknown bacterial groups [Microbial Community Analysis (MiCA) database] (41).

Statistical analysis.

T-RF size and abundance data from GeneMapper were compiled into a data matrix using Sequentix software (Sequentix, Klein Raden, Germany). These data were normalized (individual T-RF peak area as a proportion of total T-RF peak area within that sample), transformed by square root, and compiled into a Bray-Curtis similarity matrix using PRIMER version 6 software (Primer-E, Ivybridge, UK). T-RF data were then subjected to multivariate analysis, including hierarchical cluster analysis followed by analysis of similarity (ANOSIM). Using ANOSIM, we assessed the similarities between groups (D-IBS patients vs. healthy controls) and within groups. We computed the significance in PRIMER version 6 by permutation of group membership with 999 replicates. The test statistic R, which measures the strength of the results, ranges from −1 to 1: R = 1 signifies differences between groups, while R = 0 signifies that the groups are identical. The contribution of specific T-RFs to differences in bacterial composition between groups was assessed by similarity percentages (SIMPER). SIMPER results were used to generate pie charts of percent contribution of T-RFs within each group, after a 10% cutoff for low contributors. Biodiversity of each sample was measured by the Shannon-Weiner diversity index, while differences in biodiversity between groups were assessed by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Study population.

A total of 37 subjects were investigated. All subjects provided a fecal and a colonic mucosal sample. The study population consisted of 75% females with a mean age of 36 yr. Demographics and body mass index were similar in the two study groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of D-IBS patients and healthy controls

| D-IBS Patients (n = 16) | Healthy Controls (n = 21) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 35.6 (23–52) | 35 (21–60) |

| %Female | 69 | 81 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.6 (20.9–40.6) | 28.8 (18.1–53) |

Values are means (ranges). D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; BMI, body mass index.

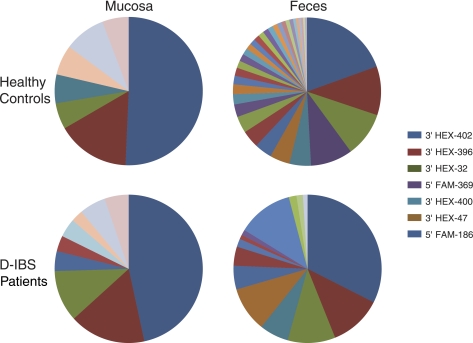

A total of 261 different Hha I-generated T-RFs, which represent different bacterial groups, were found in fecal and colonic mucosal samples from all subjects. Hae III and Msp I generated 252 and 284 T-RFs from fecal DNA samples, respectively. Thirty-six of the Hha I-generated T-RFs contributed ∼90% of the total T-RFs found in all subjects (Fig. 1, Table 2). The distribution of T-RFs differed between D-IBS patients and healthy controls and between intestinal niches (fecal vs. mucosal, Table 2). For example, 20 T-RFs found in fecal samples from healthy controls were not present in fecal samples from D-IBS patients (Table 2). The abundance (peak width × height) of 5′ FAM-187 and 3′ HEX-402 in the feces was significantly altered between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. In addition, 3′ HEX-400 was present in mucosal samples from healthy controls but not D-IBS patients, while 5′ FAM-189 and 3′ HEX-131 were found in mucosal samples from D-IBS patients but not healthy controls (Table 2). These data demonstrate compositional differences in the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. To attribute bacterial groups to these T-RFs, the MiCA database was queried (41). This database provided bacterial grouping (phylum, class, order, or family) for the majority of T-RFs that contribute to the composition of the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota in D-IBS patients and healthy controls (Table 2). The majority of T-RFs represented several bacterial groups; however, comparison of bacterial groups identified by fecal T-RFs generated by three different enzymes [Hha I, Hae III, and Msp I (Tables 2 and 3)] revealed that the order Clostridiales and the family Planctomycetaceae were consistently associated with T-RFs that contributed 90% of fecal microbiota in healthy controls but not D-IBS patients.

Fig. 1.

Terminal-restriction fragment (T-RF) fingerprinting data displaying percent contribution of T-RFs within fecal and colonic mucosal samples from patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (D-IBS) and healthy controls.

Table 2.

Percent contribution of predominant T-RFs in fecal and mucosal samples from healthy controls and D-IBS patients

| Mucosa |

Feces |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls |

D-IBS patients |

Healthy controls |

D-IBS patients |

||||||

| T-RF | %Contribution | %Positive | %Contribution | %Positive | %Contribution | %Positive | %Contribution | %Positive | Predicted Bacterial Group |

| 5′ FAM-48 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 6.2 | 1.27 ± 0.94 | 71.4 | NC | 43.7 | Lachnospiraceae |

| 5′ FAM-56 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 0 | 2.02 ± 1.23 | 85.7 | NC | 50 | |

| 5′ FAM-62 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 18.7 | 8.29 ± 1.22 | 95.2 | 10.99 ± 1.14 | 93.7 | Staphylococcaceae, Bacillaceae, Rhizobiales |

| 5′ FAM-185 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 25 | 3.43 ± 1.02 | 80.9 | 3.76 ± 1.13 | 81.2 | Anaerolineaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Planctomycetaceae |

| 5′ FAM-186 | 5.17 ± 0.49 | 47.6 | 10.37 ± 0.56 | 56.2 | 8.84 ± 1.69 | 100 | 9.41 ± 1.22 | 87.5 | Carnobacteriaceae, Listeriaceae |

| 5′ FAM-187 | NC | 14.3 | NC | 25 | 0.78 ± 0.64 | 57.1 | 1.27 ± 0.57† | 56.2 | Clostridiales, Kineosporiineae, Desulfurobacteriaceae, Prevotellaceae, Acetobacteraceae, Xanthomonadaceae |

| 5′ FAM-189 | NC | 33.3 | 4.01 ± 0.38 | 43.7 | 3.44 ± 0.79 | 80.9 | 4.68 ± 0.94 | 81.2 | Clostridiales |

| 5′ FAM-224 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 0 | 1.13 ± 0.66 | 61.9 | NC | 50 | Flavobacteriaceae, Alicyclobacillaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Haliangiaceae |

| 5′ FAM-369 | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 33.3 | 2.4 ± 0.23 | 31.2 | NC | 28.6 | NC | 12.5 | Actinomycetales |

| 5′ FAM-377 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 0 | 2.49 ± 0.79 | 76.2 | NC | 18.7 | Clostridiales, Planctomycetaceae, Methylobacteriaceae, Thermoanaerobacteraceae, Deferribacterales Incertae Sedis, Caldilineaceae, Actinobacteria |

| 5′ FAM-384 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 6.2 | 0.84 ± 0.64 | 61.9 | NC | 25 | Anaerolineaceae, Incertae Sedis XII, Veillonellaceae, Planctomycetaceae |

| 5′ FAM-402 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 1.44 ± 0.53 | 66.7 | NC | 31.2 | Anaerolineaceae |

| 5′ FAM-548 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 0 | 0.53 ± 0.41 | 38.1 | NC | 25 | Nitriliruptoraceae, Heliobacteriaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Helicobacteraceae |

| 5′ FAM-550 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 0 | 0.9 ± 0.66 | 61.9 | NC | 25 | Nitriliruptoraceae, Anaerolineaceae, Streptococcaceae, Thermoanaerobacteraceae, Heliobacteriaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Incertae Sedis XIV |

| 5′ FAM-561 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 1.44 ± 5.53 | 52.4 | 1.08 ± 0.45 | 37.5 | Clostridiales, Planctomycetaceae, Alteromonadaceae |

| 5′ FAM-562 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 6.2 | 1.14 ± 0.57 | 57.1 | NC | 37.5 | Lachnospiraceae, Alteromonadaceae, Saccharospirillaceae, Halomonadaceae, Pseudomonadaceae |

| 5′ FAM-565 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 0 | 1.17 ± 0.66 | 66.7 | NC | 25 | Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Comamonadaceae, Rhodocyclaceae, Methylococcaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, Ectothiorhodospiraceae |

| 5′ FAM-580 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.48 | 38.1 | NC | 37.5 | Vibrionales |

| 3′ HEX-32 | 8.2 ± 0.41 | 47.6 | 5.32 ± 0.43 | 50 | 3.28 ± 1.8 | 90.5 | 0.92 ± 0.59 | 50 | Deinococcaceae, Gemmatimonadaceae |

| 3′ HEX-47 | 5.23 ± 0.39 | 47.6 | 4.87 ± 0.37 | 43.7 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | NBG |

| 3′ HEX-61 | NC | 0 | NC | 6.2 | 0.42 ± 0.47 | 52.4 | NC | 37.5 | Syntrophomonadaceae, Rubritaleaceae |

| 3′ HEX-62 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 18.7 | 3.94 ± 0.95 | 80.9 | 8.85 ± 1.26 | 93.7 | Helicobacteraceae, Thermomicrobiaceae |

| 3′ HEX-64 | NC | 0 | NC | 6.2 | 1.13 ± 0.66 | 66.7 | NC | 50 | Bacteroidaceae, Alphaproteobacteria, Myxococcales |

| 3′ HEX-79 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 0 | 1.92 ± 0.74 | 93.5 | NC | 50 | Lachnospiraceae |

| 3′ HEX-131 | NC | 38.1 | 3.16 ± 0.41 | 43.7 | 1.6 ± 0.95 | 93.5 | 0.85 ± 0.39 | 43.7 | Bacteroidaceae, Chitinophagaceae, Planctomycetaceae, |

| 3′ HEX-142 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 0 | 1.09 ± 0.78 | 61.9 | NC | 43.7 | Planctomycetaceae, Spirochaetaceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae |

| 3′ HEX-183 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 0.39 ± 0.48 | 38.1 | NC | 37.5 | |

| 3′ HEX-267 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 0.94 ± 0.95 | 71.4 | NC | 37.5 | Desulfovibrionales, Vibrionales |

| 3′ HEX-303 | NC | 0 | NC | 6.2 | 1.05 ± 0.8 | 66.7 | NC | 50 | Bacillales |

| 3′ HEX-317 | NC | 0 | NC | 0 | 0.59 ± 0.62 | 57.1 | NC | 17.8 | |

| 3′ HEX-393 | NC | 9.5 | NC | 0 | 1.69 ± 0.5 | 42.8 | 1.61 ± 0.44 | 50 | Flavobacteriales |

| 3′ HEX-394 | NC | 14.3 | NC | 12.5 | 0.74 ± 0.3 | 42.8 | NC | 31.2 | NBG |

| 3′ HEX-396 | 14.43 ± 0.67 | 61.9 | 15.37 ± 0.64 | 62.5 | 9.61 ± 1.1 | 85.7 | 10.37 ± 1.05 | 81.2 | Clostridiales, Burkholderiales |

| 3′ HEX-400 | 5.69 ± 0.27 | 33.3 | NC | 25 | 4.24 ± 0.66 | 66.7 | 5.76 ± 0.89 | 68.7 | Firmicutes, Proteobacteria |

| 3′ HEX-402 | 45.88 ± 0.88 | 76.2 | 42.98 ± 0.8 | 75 | 17.57 ± 1.45 | 100 | 29.33 ± 2.1* | 100 | NBG |

| 3′ HEX-404 | NC | 4.8 | NC | 18.7 | 0.43 ± 0.47 | 47.6 | NC | 31.2 | NBG |

Values are means ± SE of normalized terminal-restriction fragment (T-RF) peak abundance from top 90% of contributors (predominant contributors) within each group. Predicted bacterial group refers to bacterial phylum, class, order, or family assigned to a T-RF based on the resolution of the Microbial Community Analysis (MiCA) database (41). NBG, numerous bacterial groups (i.e., MiCA database provided a large number of bacterial groups for this T-RF that are too numerous to list); NC, no contribution (i.e., T-RF does not contribute to the top 90% of T-RFs in a sample). Underlined bacterial groups are those consistently identified by T-RFs generated from 3 restriction enzymes (Hha I, Hae III, and Msp I) that contributed 90% of microbiota in healthy controls but not D-IBS patients. Significantly different from % contribution in healthy controls:

P = 0.04;

P = 0.003.

Table 3.

Hae III- and Msp I-generated T-RFs that contribute to 90% of the fecal microbiota in healthy controls but not D-IBS patients

| Feces |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls |

D-IBS Patients |

||||

| %Contribution | %Positive | %Contribution | %Positive | Predicted Bacterial Group | |

| Hae III T-RFs | |||||

| 5′ FAM-316 | 2.4 | 95.4 | NC | 100 | Clostridiales |

| 5′ FAM-297 | 1.2 | 91.3 | NC | 84.6 | Cyanobacteria, Synergistaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Sphingomonadaceae |

| 5′ FAM-221 | 1.2 | 82.6 | NC | 69.2 | Ktedonobacteraceae, Burkholderiales, Xanthomonadales, Planctomycetaceae |

| 3′ HEX-218 | 0.9 | 69.6 | NC | 76.9 | Acidimicrobidae, Anaerolineaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Planctomycetaceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae |

| Msp I T-RFs | |||||

| 5′ FAM-478 | 0.7 | 62.5 | NC | 71.4 | Cytophagaceae, Chromatiaceae |

| 5′ FAM-221 | 1.0 | 79.2 | NC | 85.7 | Clostridiales |

| 5′ FAM-67 | 0.8 | 70.8 | NC | 57.1 | Acidimicrobineae, Actinomycetales, Solirubrobacterales, Ruminococcaceae, Planctomycetaceae, Rhodospirillales, Comamonadaceae |

| 3′ HEX-84 | 2.9 | 95.8 | NC | 92.8 | Actinomycetales |

| 3′ HEX-68 | 1.6 | 87.5 | NC | 57.1 | Desulfobacteraceae |

Underlined bacterial groups are those consistently identified by T-RFs generated from Hae III, Hha I, or Msp I that contributed 90% of microbiota in healthy controls but not D-IBS patients.

Biodiversity of T-RFLP profiles.

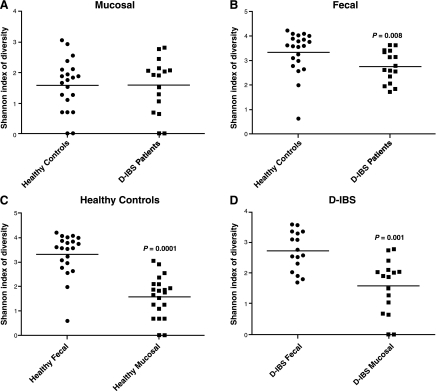

The Shannon-Weiner diversity index was used to determine the biodiversity (richness and evenness of T-RFs) of T-RFLP profiles from intestinal samples. A significant 1.2-fold decrease (2.7 ± 0.65 for D-IBS patients and 3.3 ± 0.86 for healthy controls, P = 0.008) in biodiversity was found in Hha I-generated T-RFs from fecal samples from D-IBS patients compared with healthy controls (Fig. 2B). Hae III-generated T-RFs for 34 fecal samples [13 from D-IBS patients and 21 from healthy controls (3 samples from D-IBS patients failed to yield detectable T-RFs following digestion)] demonstrated a significant 1.06-fold decrease in biodiversity (3.47 ± 0.37 for D-IBS patients and 3.67 ± 0.60 for healthy controls, P = 0.015) in fecal samples from D-IBS patients compared with healthy controls. A 1.04-fold decrease in biodiversity in Msp I-generated T-RFs from D-IBS fecal samples failed to reach statistical significance (0.979 ± 0.02 for D-IBS patients and 0.983 ± 0.02 for healthy controls, P = 0.296). No significant differences were observed in biodiversity from mucosal samples between D-IBS patients and healthy controls (1.6 ± 0.89 and 1.6 ± 0.84, respectively, P = 1) using Hha I-generated T-RFs.

Fig. 2.

Shannon-Weiner biodiversity index in mucosal samples from healthy controls and D-IBS patients (A), fecal samples from healthy controls and D-IBS patients (B; P = 0.008), fecal and mucosal samples from healthy controls (C; P = 0.0001), and fecal and mucosal samples from D-IBS patients (D; P = 0.001).

We also compared the biodiversity of fecal and mucosal niches within each group. We observed a significant increase in biodiversity in the fecal niche compared with the mucosal niche in both groups, with a 1.7-fold increase (2.7 ± 0.65 for feces and 1.6 ± 0.89 for mucosa, P = 0.001) in D-IBS patients and a 2.1-fold increase (3.3 ± 0.86 for feces and 1.6 ± 0.84 for mucosa, P = 0.0001) in healthy controls (Fig. 2, C and D).

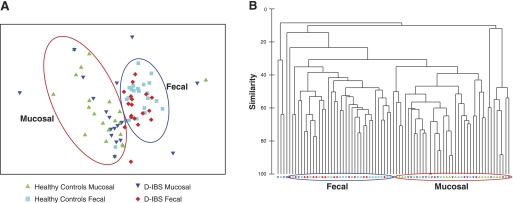

Multivariate analysis of T-RFLP profiles.

Nonmultidimensional scaling (nMDs) of T-RF profiles generated by Hha I-digested PCR products of samples obtained from all subjects (D-IBS patients and healthy controls) demonstrated that the community profiles in fecal and colonic mucosal niches are clearly distinct from one another (Fig. 3A). Hierarchal clustering analysis of T-RF profiles confirmed this observation (Fig. 3B). The degree of separation (as determined by R value, where R = 1 indicates complete separation between groups) between fecal and mucosal niches was more evident when these two niches were compared in healthy controls than in D-IBS patients, although both were statistically significant (R = 0.41, P = 0.001 in healthy controls; R = 0.22, P = 0.001 in D-IBS patients; Table 4).

Fig. 3.

A: nonmultidimensional scaling analysis of T-RF profiles generated from fecal and mucosal samples from D-IBS patients and healthy controls. B: hierarchical cluster analysis of T-RF data from fecal and mucosal samples from D-IBS patients and healthy controls. Red and blue circles represent the majority of mucosal and fecal samples, respectively.

Table 4.

Analysis of similarity test for global community composition

| Global Test (R) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Feces: D-IBS patients (n = 16) vs. healthy controls (n = 21) | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Mucosa: D-IBS patients (n = 16) vs. healthy controls (n = 21) | −0.02 | 70.8 |

| D-IBS patients: feces (n = 16) vs. mucosa (n = 16) | 0.22 | 0.001* |

| Healthy controls: feces (n = 21) vs. mucosa (n = 21) | 0.41 | 0.001* |

Data are from Hha I-generated T-RF length polymorphism fingerprints.

Statistically significant.

No distinct separation by nMDs or hierarchal clustering was observed between D-IBS patients and healthy controls from fecal or mucosal niches (Table 4). T-RF profiles were also generated for fecal samples (13 from D-IBS patients and 21 from healthy controls) using Hae III or Msp I restriction enzymes (3 samples from D-IBS patients failed to yield detectable T-RFs following digestion). nMDs and hierarchal clustering of T-RFs generated by Hae III and Msp I did not detect a distinct separation between D-IBS patients and healthy controls from fecal samples (R = −0.035, P = 0.687 for Hae III; R = −0.001, P = 0.470 for Msp I).

DISCUSSION

Several studies have investigated the composition of the intestinal microbiota in patients with IBS and healthy individuals (4, 9, 15, 16, 22, 23, 25, 26, 45). Although these studies demonstrated some differences between these two groups, the findings are not consistent. The majority of studies that characterized the intestinal microbiota in IBS patients investigated mixed populations of IBS patients (4, 42, 45) or focused on a single intestinal niche (4, 15, 16, 22, 23, 25, 42, 45, 46). Recent reports demonstrating compositional and diversity differences between intestinal luminal- and mucosal-associated microbiota in humans highlight the importance of characterizing enteric microorganisms in both niches when investigating the role of the microbiota in intestinal diseases (11, 29). Only two studies have investigated the intestinal microbiota of luminal and mucosal niches in patients with IBS (6, 9). In a recent study, using culture and quantitative real-time PCR (6), we investigated the intestinal microbiota in fecal and colonic mucosal samples from D-IBS patients and healthy controls. We found a significantly lower concentration of aerobic bacteria and a higher concentration of Lactobacillus species in fecal samples from D-IBS patients than in healthy controls. These two techniques identified no differences in the mucosal-associated microbiota between the groups. However, this study was limited to the analysis of a finite number of predetermined bacterial groups within the intestinal microbiota. Codling et al. (9) used denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (an alternate fingerprinting technique to the method used in our current study) to investigate the intestinal microbiota in a mixed population of IBS patients. Similar to our findings, Codling et al. reported a greater variation of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis profiles in fecal samples from healthy controls than IBS patients. However, in contrast to our findings, Codling et al. reported no differences in the variability between the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota in IBS patients. The discrepancy between the two studies may relate to the mixed population, preparation prior to mucosal sample collection, or inclusion of only nine IBS patients and no healthy controls for the mucosal analysis in the study of Codling et al. Thus our current study is the first to use a molecular fingerprinting technique in a comprehensive investigation of fecal and unprepared colonic mucosal samples from a large group of patients with a specific subtype of IBS (D-IBS) and healthy controls.

Analysis of the contribution of T-RFs to the composition of the intestinal microbiota demonstrated a considerable overlap in the predominant T-RFs within the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota in D-IBS patients and healthy controls. However, D-IBS fecal and mucosal samples contained T-RFs that were not present in healthy control samples, and vice versa. These findings demonstrate obvious compositional differences in specific bacterial groups (as represented by T-RFs) in the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. On the basis of comparisons with the MiCA database, the majority of T-RFs for fecal and mucosal samples were associated with multiple bacterial groups. However, using three different restriction enzymes on our fecal samples, we were able to determine whether a bacterial group(s) was consistently represented by three different enzyme-generated T-RFs that contributed to the majority of the fecal microbiota. We found that the order Clostridiales and the family Planctomycetaceae were consistently represented by Hha I-, Hae III-, and Msp I-generated T-RFs that contributed 90% of the fecal microbiota in healthy controls but not D-IBS patients. Previous reports showed a reduction of Clostridium coccoides in IBS patients that is in line with our findings (23). Interestingly, a reduction in the order Clostridiales has also been reported in ileal Crohn's disease (47). The order Clostridiales encompasses many bacterial species, including the protective bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. It is therefore speculated that the absence of protective bacterial species from the order Clostridiales may be associated with D-IBS. A more sensitive molecular technique that classifies the intestinal microbiota at a species level will enable further investigation of this finding. The family Planctomycetaceae is a low-abundance member of the normal intestinal microbiota (1). The importance of our finding of reduced abundance of this bacterial group in D-IBS patients is unclear, as the role of this group of organisms in the intestinal tract has not been investigated in depth.

Although we found compositional differences in the fecal microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls with respect to specific T-RFs, we did not find a clear separation between these two groups with nMDs or hierarchal clustering. This suggests that the differences in composition of the microbiota between D-IBS patients and healthy controls are due to the relative abundances of specific bacterial groups that do not affect the overall composition of the intestinal microbiota. In support of this concept, it has been recently demonstrated that specific bacterial species (Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis) that do not affect the overall composition of the intestinal microbiota independently drive colonic disease in the presence of the endogenous microbiota in a horizontally and vertically transmissible mouse model of ulcerative colitis (12).

Our study demonstrates a significantly lower level of fecal microbial biodiversity in patients with D-IBS compared with healthy controls. Additionally, our study demonstrates, for the first time, a significantly higher level of microbial biodiversity in fecal- than in mucosal-associated communities within D-IBS patients and healthy controls. The increase in biodiversity in fecal compared with mucosal samples is greater in the healthy controls than in D-IBS patients. This observation requires further investigation to determine whether the intestinal microbiota in D-IBS patients is distributed differently between the fecal and mucosal niches compared with the microbiota in a healthy intestine. The biodiversity in the human gut is a result of coevolution between host and microbe (3) and has been shown to be stable over time in healthy individuals (48). Thus a departure from the normal biodiversity of the intestinal microbiota may reflect a disease state in the gut. For example, a reduction in enteric bacterial biodiversity has been reported in inflammatory bowel diseases (24, 28, 37, 38). It can be speculated that a reduction in bacterial biodiversity allows for certain members of the intestinal microbiota to flourish and affect intestinal function, such as regulation of inflammation or motility, and therefore perpetuate GI symptoms.

Despite the meticulous efforts used in our study to preserve and characterize the microbiota from different intestinal niches, certain limitations were encountered. 1) T-RFLP was unable to provide the resolution necessary to identify the bacterial species in the intestinal microbiota that are altered between D-IBS patients and healthy controls. We were able to assign a bacterial “phylum, class, order, or family” to most T-RFs. Although this level of characterization provides interesting insight into the intestinal microbiota associated with D-IBS patients, bacterial families encompass many bacterial genera and species. Thus, on the basis of these data sets, it is difficult to make definitive conclusions regarding the association of specific bacterial groups with D-IBS. 2) It is important to remember that T-RFLP fingerprinting is limited to the analysis of only the predominant members (usually 30–50 T-RFs) of complex microbial communities (7). Not surprisingly then, our study found that 34 T-RFs contributed 90% of the fecal microbiota in healthy controls. Hence, it is possible that differences in less abundant bacteria were not detected by this technique. 3) The biopsies analyzed in this study were taken during unprepared flexible sigmoidoscopy to avoid the effects of bowel cleansing agents on the intestinal microbiota. The biopsies were taken from the distal colon just above the rectosigmoid junction. This site was selected because it provides a clear anatomic point to enable consistent collection of mucosal samples and to minimize the discomfort of the subject. However, the microbiota of this colonic region may not be representative of the microbiota of the whole colon, and we did not collect biopsies from more proximal colonic regions.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated compositional and biodiversity differences in the intestinal microbiota between patients with D-IBS and healthy controls. Our study does not address whether these differences are an etiological cause or an effect of the disorder, but it does provide a rationale for further investigation of the role of the intestinal microbiota in the pathogenesis of IBS. Our findings emphasize the importance of investigating the fecal- and mucosal-associated microbiota in this disorder, as well as the need for techniques with higher resolution (e.g., high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene), which may enable deeper characterization of the intestinal microbiota and identification of the specific bacterial groups that are altered in IBS.

GRANTS

This study was funded by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-084294 and DK-075621 awarded to Y. Ringel.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jennica Siddle, Nikki McCoy, Sheena Neil, and Daniel Williamson for their contribution to the study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, Engstrand L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One 3: e2836, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azpiroz F, Bouin M, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Poitras P, Serra J, Spiller RC. Mechanisms of hypersensitivity in IBS and functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 62–88, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science 307: 1915–1920, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balsari A, Ceccarelli A, Dubini F, Fesce E, Poli G. The fecal microbial population in the irritable bowel syndrome. Microbiologica 5: 185–194, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Caenepeel P, Janssens J, Vantrappen G, Eyssen H, Coremans G. Interdigestive myoelectric complex in germ-free rats. Dig Dis Sci 34: 1180–1184, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carroll IM, Chang YH, Park J, Sartor RB, Ringel Y. Luminal- and mucosal-associated intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Pathog 2: 19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carroll IM, Ringel-Kulka T, Ringel Y. Quantitating and identifying the organisms. In: Probiotics: A Clinical Guide, edited by Floch MH, Kim A. S. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK, 2009, p. 55–69 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choi CH, Jo SY, Park HJ, Chang SK, Byeon JS, Myung SJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in irritable bowel syndrome: effect on quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol 45: 679–683, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Codling C, O'Mahony L, Shanahan F, Quigley EM, Marchesi JR. A molecular analysis of fecal and mucosal bacterial communities in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 55: 392–397, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, Rosenquist M, Jarnerot G, Tysk C, Apajalahti J, Engstrand L, Jansson JK. Molecular analysis of the gut microbiota of identical twins with Crohn's disease. ISME J 2: 716–727, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Durban A, Abellan JJ, Jimenez-Hernandez N, Ponce M, Ponce J, Sala T, D'Auria G, Latorre A, Moya A. Assessing gut microbial diversity from feces and rectal mucosa. Microb Ecol 61: 123–133, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garrett WS, Gallini CA, Yatsunenko T, Michaud M, DuBois A, Delaney ML, Punit S, Karlsson M, Bry L, Glickman JN, Gordon JI, Onderdonk AB, Glimcher LH. Enterobacteriaceae act in concert with the gut microbiota to induce spontaneous and maternally transmitted colitis. Cell Host Microbe 8: 292–300, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guglielmetti S, Mora D, Gschwender M, Popp K. Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life—a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 33: 1123–1132, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Husebye E, Hellstrom PM, Sundler F, Chen J, Midtvedt T. Influence of microbial species on small intestinal myoelectric activity and transit in germ-free rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G368–G380, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kassinen A, Krogius-Kurikka L, Makivuokko H, Rinttila T, Paulin L, Corander J, Malinen E, Apajalahti J, Palva A. The fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients differs significantly from that of healthy subjects. Gastroenterology 133: 24–33, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krogius-Kurikka L, Lyra A, Malinen E, Aarnikunnas J, Tuimala J, Paulin L, Makivuokko H, Kajander K, Palva A. Microbial community analysis reveals high level phylogenetic alterations in the overall gastrointestinal microbiota of diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome sufferers. BMC Gastroenterol 9: 95, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lea R, Whorwell PJ. Quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics 19: 643–653, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lesniewska V, Rowland I, Laerke HN, Grant G, Naughton PJ. Relationship between dietary-induced changes in intestinal commensal microflora and duodenojejunal myoelectric activity monitored by radiotelemetry in the rat in vivo. Exp Physiol 91: 229–237, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS, Schlegel ML, Tucker TA, Schrenzel MD, Knight R, Gordon JI. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320: 1647–1651, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 130: 1480–1491, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lydiard RB. Irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety, and depression: what are the links? J Clin Psychiatry 62 Suppl 8: 37–46, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyra A, Rinttila T, Nikkila J, Krogius-Kurikka L, Kajander K, Malinen E, Matto J, Makela L, Palva A. Diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome distinguishable by 16S rRNA gene phylotype quantification. World J Gastroenterol 15: 5936–5945, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malinen E, Rinttila T, Kajander K, Matto J, Kassinen A, Krogius L, Saarela M, Korpela R, Palva A. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol 100: 373–382, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, Nalin R, Jarrin C, Chardon P, Marteau P, Roca J, Dore J. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut 55: 205–211, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matto J, Maunuksela L, Kajander K, Palva A, Korpela R, Kassinen A, Saarela M. Composition and temporal stability of gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome—a longitudinal study in IBS and control subjects. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 43: 213–222, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maukonen J, Satokari R, Matto J, Soderlund H, Mattila-Sandholm T, Saarela M. Prevalence and temporal stability of selected clostridial groups in irritable bowel syndrome in relation to predominant faecal bacteria. J Med Microbiol 55: 625–633, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Brandt LJ, Quigley EM. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut 59: 325–332, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ott SJ, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth DF, Hampe J, Brant O, Folsch UR, Timmis KN, Schreiber S. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 53: 685–693, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ouwehand AC, Salminen S, Arvola T, Ruuska T, Isolauri E. Microbiota composition of the intestinal mucosa: association with fecal microbiota? Microbiol Immunol 48: 497–500, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? A systematic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil 18: 595–607, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Parkes GC, Sanderson JD, Whelan K. Treating irritable bowel syndrome with probiotics: the evidence. Proc Nutr Soc 69: 187–194, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, Mareya SM, Shaw AL, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med 364: 22–32, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, Kane SV, Kong Y. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 145: 557–563, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ringel Y, Carroll IM. Alterations in the intestinal microbiota and functional bowel symptoms. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 19: 141–150, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ringel Y, Ringel-Kulka T, Maier D, Carroll I, Galanko JA, Leyer G, Palsson OS. Probiotic bacteria: probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders—a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol 45: 518–525, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scanlan PD, Shanahan F, O'Mahony C, Marchesi JR. Culture-independent analyses of temporal variation of the dominant fecal microbiota and targeted bacterial subgroups in Crohn's disease. J Clin Microbiol 44: 3980–3988, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seksik P, Rigottier-Gois L, Gramet G, Sutren M, Pochart P, Marteau P, Jian R, Dore J. Alterations of the dominant faecal bacterial groups in patients with Crohn's disease of the colon. Gut 52: 237–242, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sharara AI, Aoun E, Abdul-Baki H, Mounzer R, Sidani S, Elhajj I. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am J Gastroenterol 101: 326–333, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall T, Burcal L, Mpande CN, Jenkins N, Jovov B, Abdo Z, Sandler RS, Keku TO. Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes 1: 138–147, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shyu C, Soule T, Bent SJ, Foster JA, Forney LJ. MiCA: a web-based tool for the analysis of microbial communities based on terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphisms of 16S and 18S rRNA genes. Microb Ecol 53: 562–570, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Si JM, Yu YC, Fan YJ, Chen SJ. Intestinal microecology and quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol 10: 1802–1805, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sondergaard B, Olsson J, Ohlson K, Svensson U, Bytzer P, Ekesbo R. Effects of probiotic fermented milk on symptoms and intestinal flora in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol 46: 663–672, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spiegel BM. The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 11: 265–269, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Swidsinski A, Weber J, Loening-Baucke V, Hale LP, Lochs H. Spatial organization and composition of the mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol 43: 3380–3389, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tana C, Umesaki Y, Imaoka A, Handa T, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S. Altered profiles of intestinal microbiota and organic acids may be the origin of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 22: 512–519, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, Andersson AF, Lucio M, Zheng Z, Jarnerot G, Tysk C, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology 139: 1844–1854, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zoetendal EG, Akkermans AD, De Vos WM. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 3854–3859, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zoetendal EG, von Wright A, Vilpponen-Salmela T, Ben-Amor K, Akkermans AD, de Vos WM. Mucosa-associated bacteria in the human gastrointestinal tract are uniformly distributed along the colon and differ from the community recovered from feces. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 3401–3407, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]