Abstract

Objective. To develop, integrate, and assess an introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) in providing pharmaceutical care to patients at senior centers (Silver Scripts).

Design. First-year pharmacy students learned and practiced the pharmaceutical care process in the classroom to prepare for participation in the Silver Scripts program, in which the students, under faculty mentorship, conducted comprehensive medication reviews for senior citizens attending senior centers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Assessment. Students, preceptors, and senior center staff members indicated the experience was positive. Specifically, first-year students felt they gained benefit both from an educational standpoint and in their own personal growth and development, while staff contacts indicated the patients appreciated the interaction with the students.

Conclusion. The Silver Scripts experience is a model for linking classroom experiences and experiential learning. The cycle of experiencing, reflecting, and learning has provided not only a meaningful experience for our P1 students but also a worthwhile focused review of seniors’ medication use. This experience could be used as a model for other colleges and schools of pharmacy and their communities.

Keywords: experiential education, introductory pharmacy practice experience, community outreach, pharmacy student, professionalism, pharmaceutical care

INTRODUCTION

Since Hepler and Strand introduced the pharmaceutical care philosophy in 1990, pharmacy educators and practitioners have been developing patient-centered practice models, striving to move toward ideal pharmacist-provided patient care.1 The incorporation of medication therapy management (MTM) services within the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and the Medicare Prescription Medication Benefit (Part D) presented a strategy for pharmacists to provide and be compensated for pharmaceutical care.2-4 However, MTM is still not being provided in many US communities. Pharmacists and students have cited barriers to implementing pharmacist-provided patient care, including the need for students to practical experience in providing patient care.5-6

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education's (ACPE's) 2007 standards recognize students’ need to develop practitioner abilities in authentic practice settings and include a greater emphasis on experiential education opportunities that involve students in direct patient care environments under the mentorship of experienced practitioners.7 While these standards signify progress toward providing more comprehensive training for pharmacy students, they also present an opportunity to meet patient-care needs in the community. The inherent challenge for colleges and schools of pharmacy is to identify “real-world” practice environments and develop programs that can provide students with experiences that enhance their classroom learning. This paper describes the development, implementation, and evaluation of the Silver Scripts program at the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy.

DESIGN

Beginning in the 2003-2004 academic year, pharmacy faculty members at the University of Pittsburgh designed a patient-care immersion process for students to learn and observe pharmacist-provided care in the community. This 2-semester introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE) was integrated into the first-year Profession of Pharmacy 1 and 2 courses. Preparation for the experience began in the classroom and ultimately resulted in students, under faculty mentorship, conducting comprehensive medication reviews for community-dwelling senior citizens attending senior centers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The program was titled Silver Scripts to reflect the 2 key aspects of the program: senior citizens (silver) and medication review (prescriptions or “scripts”). The learning objectives of the experience were: (1) to practice basic pharmaceutical care skills, such as establishing relationships, identifying drug-related needs, and providing documentation in a standardized, replicable format using the MTM Core Elements as a guide8; (2) to demonstrate effective communication skills during patient care interviews; and (3) to develop professional identity through interacting with seniors.

Classroom Preparation for Silver Scripts

In the first semester of the Profession of Pharmacy course, students read and discussed literature explaining the principles of pharmaceutical care and how paradigms affect the way pharmacists and other healthcare providers view practice. Students interviewed panelists who practiced pharmaceutical care to learn how the concept was incorporated in the real world. The goal of these learning exercises was to provide students with an understanding of the concept of pharmaceutical care as a basis for the provision of direct patient care.

Through the first semester, students learned communication strategies necessary for establishing a therapeutic relationship by observing course faculty members as they demonstrated the steps involved in completing a comprehensive medication review, as well as by role playing. Students worked through the steps of the pharmaceutical care process using the MTM core elements as a guide, first with patient cases, then in mock interviews. During the 2007-2008 academic year, students conducted mock patient interviews with one another. During the 2008-2009 academic year, students conducted mock patient interviews with standardized patient actors.9 The patient scenarios were basic so that students could experiment with communication strategies. Following each of the mock encounters, students completed a personal medication record, medication action plan, and physician consultation letter. Debriefing discussions were held in class to allow the students and faculty members to reflect on what worked well, what did not work, and how the students could overcome their uneasiness with their new role as a practitioner. The purpose of these sessions was to introduce students to the communication skills needed to provide pharmaceutical care.

The Silver Scripts Community Practice Experience

In the second and third months of the spring semester, groups of 10 first-year pharmacy (P1) students were assigned to a senior center in Pittsburgh, along with a faculty preceptor and 1 or 2 fourth-year pharmacy (P4) students. P1 students were paired to meet with senior citizens who volunteered to have an individualized patient care interview. Student pairs were expected to begin to establish a relationship with a senior citizen; obtain a complete medication history, including subjective and objective information; and perform a comprehensive medication review. Given their limited drug therapy knowledge, the P1 students were instructed to avoid making recommendations or providing counseling to the senior citizens. P4 students were available to assist the P1 students with the interview process and to provide basic drug therapy information, including medication names and dosing instructions. Faculty preceptors modeled the patient care process for the students by reviewing the seniors’ medication regimens and addressing any specific concerns.

After completing the assessment and care plan for each senior citizen, the faculty preceptor was responsible for making patient-specific recommendations and referring patients to appropriate health care practitioners and resources if needed. P1 students then were responsible for completing the final documentation for each senior citizen, including the personal medication record, medication action plan, and physician consultation letter. The personal medication record and medication action plan were written by the students during the experience and reviewed by the preceptor before being provided to the patient.

On the day of their first visit, students were instructed to arrive at the senior center 30 minutes prior to the first scheduled patient appointment time to meet with the senior center coordinator, preceptor, and P4 students, and to set up a location within the center for the interviews that was conducive to patient interviews. Students and preceptors worked together to identify those who were interested in receiving a medication evaluation. As patients were identified, students worked in pairs to conduct the patient interview and comprehensive medication review. Patient encounters lasted 10-30 minutes, depending on the need(s) and interest of the patient. At the end of the each encounter, P1 students provided the preceptor with a brief verbal overview of the patient. With the P1 students observing, preceptors then met with each patient to review any necessary recommendations. Patients were given a personal medication record and reminded of the 1-month follow-up visit.

As required for the previous interview assignments, students documented each patient care encounter according to the MTM core elements and completed a personal medication record, medication action plan, and physician consultation letter for each patient encounter in which they were the lead interviewer. Student pairs were required to submit a written reflection of their experience for each of the 2 senior center visits.

Students and faculty members visited senior centers twice, providing an initial medication review during the first visit and follow-up care during the second visit a month later. The follow-up visit provided an opportunity for students and preceptors to assess patient progress. For example, if during the initial visit, a student found that a patient had a problem with medication access, the P1 student, under faculty preceptor supervision, was responsible for investigating patient-assistance programs that could benefit the senior citizen and reviewing this information with the senior citizen during the follow-up visit. The 1-month timeframe allowed for additional student instruction and debriefing while mirroring a reasonable, average timeframe for patient care follow-up in the community setting.

Students and faculty preceptors spent approximately 3 hours at the senior center during each of the site visits. The program modeled authentic pharmacist-provided care in the community, including a comprehensive review and assessment of patients’ medication regimens and allowing follow-up on their drug-related needs based on the MTM core elements. Course faculty members collaborated with other faculty and staff members in the Office of Experiential Learning to establish community partnerships with 13 senior centers. Each center agreed to 2 student visits, 1 month apart. Center coordinators helped recruit senior citizens by making announcements and posting flyers about the Silver Scripts program.

Faculty and pharmacy resident practitioner volunteers served as preceptors for the students and were responsible for coordinating all activities and student learning at each senior center. Preceptors met a few days prior to the initial senior center visit to review requirements for the students’ experience, including patient documentation forms, patient education materials, and a patient log to track the encounters. Patient confidentiality was maintained by means of preceptors assigning numbers to the patients. Students did not record any patient identification information during their encounters. The P4 students who volunteered or were assigned to this experience as a part of their APPE met with course faculty members a few days prior to the senior center visit to review the P1 students’ responsibilities and discuss their role as a preceptor-in-training. P4 students served as guides for the P1 students during their patient encounters, assisting them with communicating effectively and reviewing basic drug information. They also assisted the faculty preceptor with coordinating activities at the senior center. The P4 students were prepared for this role as they had participated in the Silver Scripts program during their P1 year and participated in an instructional meeting prior to the event.

ASSESSMENT

Surveys Conducted

Formal assessment of the Silver Scripts program was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and completed during the 2007-2009 academic years. To evaluate the Silver Scripts program, we assessed first-year students’ anticipated and perceived learning points, the impact of their interviews on patient care, and preceptor's observations on student learning. Interactions between the first- and fourth-year learners also were observed and evaluated. Staff contacts at each senior center provided feedback regarding the experience. Information was obtained by conducting an anonymous paper survey instrument containing multiple-choice and open-ended questions. Patient care-related information was recorded but no patient identifying information was included.

First-year pharmacy students completed a pre-experience survey instrument that examined their anticipated learning points and concerns with conducting a patient interview at the senior center. The post-experience survey questions examined students’ perceived learning points and the impact of the program on their learning. For both surveys, students were asked to rate their comfort level speaking with elderly patients on a 5-point scale on which 1 = least comfortable and 5 = most comfortable. Students also were asked to provide a 1-word summary of the experience before and after the program. The number of seniors evaluated, blood pressure readings performed, and drug-related problems identified were recorded by students and preceptors to assess the impact of the Silver Scripts program on patient care.

Preceptor feedback was collected through post program surveys of faculty members, resident preceptors, and fourth-year students. The faculty survey asked the preceptor to summarize observed learning points of the program for P1 and P4 students, the value that the program brought to the curriculum overall, and their observations of the interactions between P1 and P4 students. P4 students were asked to summarize what they had learned from the experience, comparing it to their first-year Silver Scripts experience. Ideas and suggestions for changes to the program were solicited from both groups. Feedback was solicited from staff coordinators at each facility through a survey instrument with multiple-choice questions. Center coordinators were asked for their overall impression of the first-year pharmacy students and their perceived benefits for the senior citizens who participated. Recommendations for changes for the next year also were solicited.

Outcomes/Findings From the Surveys

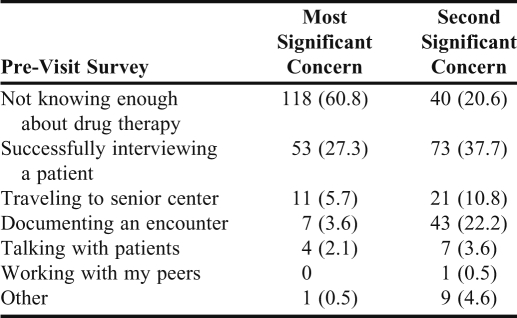

Two hundred fifteen P1 students participated in the Silver Scripts program during the 2008 and 2009 spring semesters (107 in 2008, 108 in 2009). Eighty-four percent of students had previously worked with seniors in a healthcare setting. Not knowing enough about drug therapy and patient interviewing techniques were students’ first and second greatest concerns, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

First-year Students’ Concerns Prior to Provision of Pharmaceutical Care to Elderly Patients at Senior Centers, N = 194

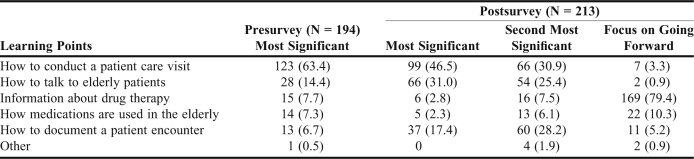

“Learning how to conduct a patient visit” was the most frequently cited student learning point prior to the experience (cited by 63% of the class, Table 2). After the program, “learning how to conduct a patient visit” was cited by 46.5% of the class as the most significant learning point. “Talking to the elderly” and “documenting a patient encounter” also were mentioned frequently as learning points before the experience, with 31% and 17.4% of the class listing these, respectively. When asked about what learning points to focus on as they go forward in the curriculum, 79% cited “information about drug therapy.”

Table 2.

Student Anticipated and Reported Learning Points Before and After Provision of Pharmaceutical Care to Elderly Patients

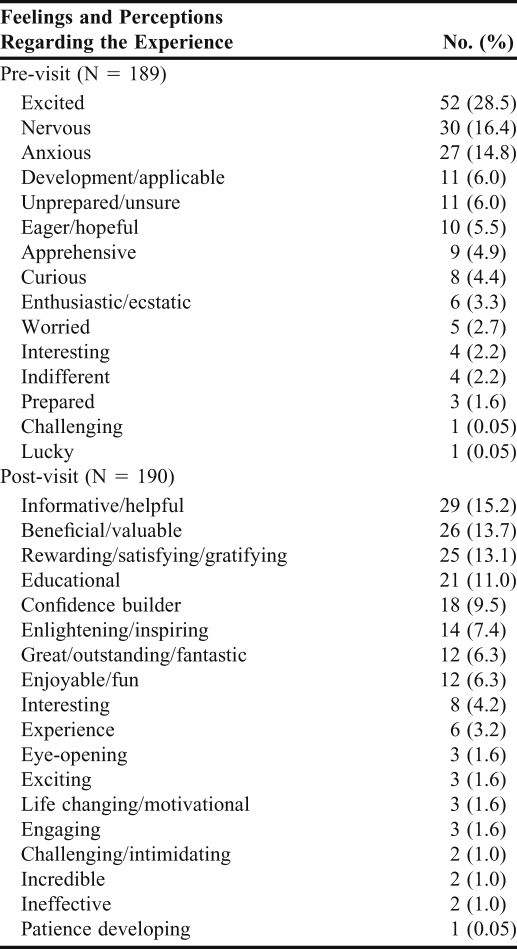

Students were asked to provide 1 word to describe what they anticipated about their Silver Scripts experience and to summarize in 1 word their perception of the experience afterward (Table 3). The most common responses were “excited,” “nervous,” and “anxious” by 60% of the class; 6% of the class felt “unprepared.” Although there was a greater variety of responses on the post experience survey, all but 2 comments were positive.

Table 3.

Students’ Anticipation of and Experience During Provision of Pharmaceutical Care to Elderly Patients at Senior Centers, N = 189

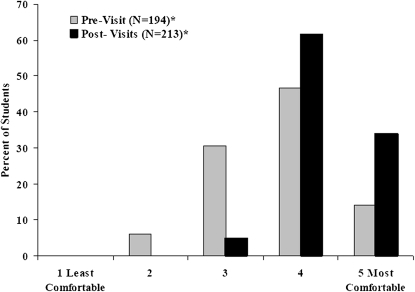

Students ranked their comfort level in speaking with the elderly on a scale of 1 to 5 (least comfortable to most comfortable) before and after the visits to the senior centers. Prior to the experience, 61% of students rated their comfort level at 4 or 5 prior to the experience (47% and 14%, respectively) compared with 95% (61% and 34%, respectively) after the experience (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comfort level speaking with the elderly (*p < 0.001).

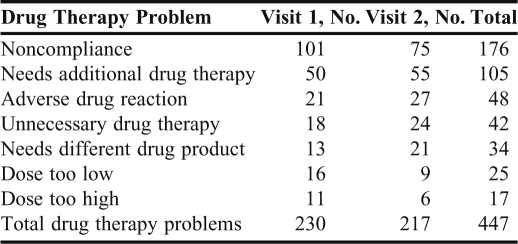

Students completed 445 interviews of 361 patients over 2 semesters. Blood pressures were taken for 373 (84%) of the patients interviewed and for an additional 214 patients who declined medication interviews. During the interviews, 447 drug-related problems were identified (Table 4), the most common of which were noncompliance and the need for additional drug therapy (39% and 32%, respectively). Examples of the reported significant interactions include: assistance obtaining glucose test strips through Medicare for a patient who had been paying out of pocket; contacting a patient's physician to address duplicate therapy; contacting a patient's physician to arrange an appointment for assessment of urinary tract infection symptoms; contacting the physician for verification of insulin dose; and recommending that one patient stop smoking.

Table 4.

Drug-Therapy Problems Identified by First-Year Pharmacy Students During Provision of Pharmaceutical Care to Elderly Patients at Senior Centers

Preceptor Feedback

Thirteen faculty members (including 6 residents) and 23 P4 students served as preceptors at participating senior centers during the spring semesters of 2008 and 2009. The top 3 learning points identified through the faculty preceptors’ observations were: interviewing patients (communication skills), processing collected information (clinical decision-making), and understanding the role of pharmacists as medication managers (professional identification). Observing that small interactions can lead to significant changes in a patient's life was an invaluable learning point for the students.

All faculty preceptors stated that the students’ interactions with patients during the Silver Scripts program provided several benefits to the overall pharmacy curriculum. Four general themes were noted. First, the experience laid a foundation on which to build patient assessment, communication, triage, and documentation techniques. Second, it impressed upon students that patients are real, their problems are real, and some situations are not straightforward, bringing a sense of reality at an early stage in the pharmacy curriculum. Third, the program allowed students to take information learned in the classroom and apply it in a real-life setting, and fourth, it allowed students to see the value of pharmacists in the community beyond the traditional dispensing role.

The faculty preceptors reported that the interactions between first-year and fourth-year pharmacy students were positive. They felt that the P1 students looked to the P4 students as role models for providing patient care, conveying professionalism, and communicating with the faculty preceptor. The fourth-year students also served as a source of encouragement to the P1 students.

When asked about the benefits to P4 students who participated as student preceptors, the faculty preceptors noted that the progress in their learning and the increase in their knowledge about applying therapeutics gained through observing the faculty preceptor were important learning points. Each faculty preceptor also noted that by serving in a preceptor role, P4 students learned how to teach and direct student learners, thus preparing them to serve as preceptors after graduation.

Student Preceptor Feedback

The fourth-year pharmacy students who served as preceptors for the first-year students were asked to provide the top 5 learning points from their participation in the Silver Scripts program. Their comments were categorized into the following general themes: using self-reflection for professional growth; gaining experience in a teaching role; fine tuning their communication and patient-interaction skills; recognizing the potential impact that first-year pharmacy students with minimal knowledge of pharmacy can make on patient care with/when given proper precepting; and, gaining an appreciation that patients may not be as independent as they appear and may need medication assistance.

When asked to compare their experience as fourth-year students to their participation in Silver Scripts as first-year students, most fourth-year students stated that they felt more in control of the patient interactions and more confident in their ability to make therapeutic recommendations. A few students saw their role only as one of providing support to the first-year students and not as providing patient care directly.

When asked about the value of their participation to the program, fourth-year students reported that their involvement allowed the P1 students to see learning growth in students further along in the curriculum; increased P1 students’ comfort level by being a first line of contact for addressing their concerns; provided an example of how to interact with a preceptor in a professional manner; and served as a preceptor extender, allowing for more oversight during patient interactions and additional feedback at sites with high patient volume.

When asked to summarize how they felt their presence was perceived by the P1 students, the faculty preceptors reported feeling that they were viewed as a teacher, information source, mentor, and role model for interaction with patients. The P4 pharmacy student preceptors reported feeling that they were viewed as a mentor, role model, and approachable resource for questions about patients as well as about life as a pharmacy student.

When faculty and student preceptors were asked to provide suggestions for improvement of the course, 1 faculty preceptor suggested including a presentation of a follow-up situation that was encountered, because some patients were not present at the students’ follow-up visit. All fourth-year pharmacy students stated that a greater number of fourth-year students should have the opportunity to participate as preceptors and that the number of site visits should be increased. Another suggestion was to carry the program across all the professional years by including P2 and P3 students.

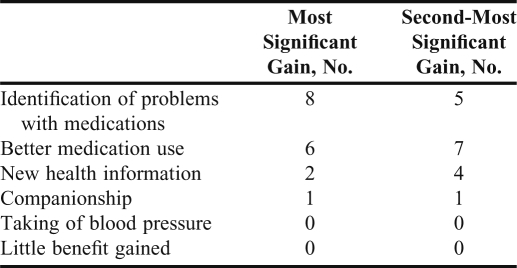

Senior Center Site Feedback

Six of the 10 senior centers that participated in the Silver Script program in 2008 returned post-visit survey instruments, and all 11 sites that participated in 2009 returned survey instruments (17 usable responses) (Table 5). The staff contact person at each center was asked to choose the most and second-most, significant gains the senior citizens at their center experienced from their interaction with the pharmacy students from the following choices: new health information, better medication use, companionship, identification of medication-related problems, measuring blood pressure, or little benefit gained. “Identification of problems with medications and better use of medications” was the highest-rated choice (76% of surveys), followed by “new health information” (35%) and “companionship” (11%). None selected the remaining options. Each staff contact person also was asked to rate the observed level of professionalism of the pharmacy students during the visits. Eight of 17 respondents rated the level of professionalism as above what was expected, 5 at what was expected for all students, and 4 as what was expected for most students. When asked if their site would like to host pharmacy students participating in the Silver Scripts program the following year, all staff contact persons responded yes except one, who reported being unsure.

Table 5.

Feedback From Contact Persons at Senior Centers Where First-Year Pharmacy Students Had Provided Pharmaceutical Care to Elderly Patients (N = 17)

DISCUSSION

Kolb defines experiential learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through transformation of experience.”10 His experiential learning cycle outlines 4 phases of experiential learning: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. We used this model to design an experience to teach the philosophy of pharmaceutical care and the practice of medication therapy management to first-year pharmacy students, most of whom had no previous exposure to pharmacists providing direct patient care.

Because they lack a frame of reference, students often have difficulty conceptualizing the skills required to function in the role of pharmacist in the pharmaceutical care model. By creating a controlled, supervised experience, we hoped to demonstrate the worth of pharmaceutical care, relieve the anxiety of interpersonal communication, and help students develop the attitudes needed to practice medication therapy management.11 This type of “real world” experience is supported by the ACPE curricular guidelines, which call for faculty members to engage students with “actual and simulated patients” to learn the practice of medication therapy management.7

Our data demonstrate the students’ overwhelming acceptance of this experience. Students reported they were more comfortable speaking with elderly patients and more confident in their ability to perform blood pressure monitoring and recognize drug therapy problems following their Silver Scripts experience. Interestingly, students identified an average of 1 drug therapy problem per patient – mostly noncompliance and need for additional drug therapy. These findings are consistent with results of a study by Rovers and colleagues12 comparing the performance of students in an APPE with clinical pharmacist practitioners caring for elderly patients in the community. The APPE students found approximately 2 drug therapy problems per patient and the clinical pharmacist practitioners found approximately 3 per patient. As with the first-year students, the APPE students most commonly identified noncompliance and the need for additional drug therapy, whereas the clinical pharmacist practitioners most often identified unnecessary drug therapy and the need for additional drug therapy. Thus, this early, closely supervised experience seemed to produce patient care results at a comparable level to that provided by students in their advanced experiences.

First-year students were able to practice communication and early clinical decision-making and to begin developing a professional identity. Fourth-year students served not only as a significant source of support for faculty members in managing the patient care experience but also as role models for first-year students. The P4 students commented that the experience allowed them to explore their role as a preceptor and to reflect on their own professional growth and knowledge.

Duncan-Hewitt and Austin proposed transforming pharmacy education to a new framework that develops “communities of practice” in order to improve learning outcomes and student professionalism.13 They point out that, in order to adopt this model of professional education in which students develop expertise through experience first and then through instruction in theory, the “curricula might need to be turned upside down.” Silver Scripts has served as the catalyst for doing so with our curriculum. The classroom work, including standardized patient experiences, allows our students to “safely” experience, reflect on, and practice patient care before being exposed to actual patients through Silver Scripts.

Initially, some of our faculty members were concerned about sending P1 students out in the community to provide care. These concerns were alleviated once faculty members realized how closely students were supervised and read the overwhelmingly positive comments from the students and senior citizens who participated in the experience. Each year, students returned to the classroom following the Silver Scripts experience eager to understand how to apply the principles learned in class to the patients they cared for in the community. Silver Scripts was an important first step in revising our curriculum to enable students to begin applying classroom knowledge and skills in a practice environment.

We identified 3 elements that contributed to the success of the program: (1) consistent preparation of the students in the classroom to provide a clear understanding of the requirements for providing patient care; (2) provision of mentoring and support to students at the sites; and (3) establishment and maintenance of relationships with senior center staff members. In the first few years of the program, only faculty members and residents worked with students at the sites. The inclusion of the P4 student preceptors provided faculty practitioners with additional observation of each patient care encounter and provided P1 students with a peer model of professionalism and patient care. Now that the program is in its eighth year, P4 students volunteer to assist based on the positive impact had with Silver Scripts as P1 students.

We cannot overemphasize the importance of building relationships and communicating with the staff members of the senior center sites. Each year, course faculty members and the director of experiential learning meet with senior center directors to explain the program to new participants. Our support staff members make numerous phone calls to senior center directors and send mailings to remind our site contacts of the dates for the site visits and the services that we intend to provide. Because the experience is scheduled for February and March each year, we occasionally have had to delay arrival at a site, cancel a day, or identify an alternative site because of unexpected weather conditions. At those times, the positive working relationships with the senior centers, flexibility of our staff members, and creativity of our faculty members allowed the student experience to continue despite unpredictable obstacles.

Silver Scripts also has served as a transformative experience for our students. The first year we offered Silver Scripts, it coincided with our first white coat ceremony. Students immediately saw how the white coat affected their relationship with the seniors, and faculty preceptors continually note the sense of pride they see in the students when caring for patients in their newly acquired white coats.14

We recognize that this experience created some cognitive dissonance for a small cohort of students who felt they needed more reassurance in order to provide care. This sense of “perfectionism” is commonly encountered among professional students.15 Beginning in the 2008-2009 academic year, we addressed this issue by including standardized patient actors in the course prior to the experience and teaching students some basic drug knowledge through the use of “Top Drug” discussions and quizzes. These additional classroom exercises resulted in most students feeling more prepared for and comfortable in their patient encounters.

SUMMARY

The Silver Scripts program has been ongoing and successful since the 2003-2004 academic year. This introductory pharmacy practice experience has provided our P1 students with an opportunity to practice basic communication and pharmaceutical care skills (establishing relationships, identifying drug-related needs, and creating documentation) and to develop a professional identity. The program has evolved beyond the initial goal of educating P1 students through a practical patient-care experience to one that also provides P4 students an opportunity to learn how to mentor and guide less-experienced students under the supervision of an experienced faculty preceptor. Seniors who participate in the program benefit from the resolution of drug-therapy problems identified by students and faculty members during their comprehensive medication reviews.

Silver Scripts has served as a foundation for important curricular changes that allow our students to first experience patient care and then seek more content and meaning as they are introduced to concepts in the classroom. Overall, Silver Scripts has been an effective course addition that has provided multiple patient care and learning opportunities that could be used as a model for other colleges and schools and communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Teresa McKaveney for her thoughtful work in the preparation and review of this manuscript and Cheri Hill and Renee Fry for their assistance with all the “behind the scenes” organization of the experience.

We also give special recognition to the many current and former faculty members, residents, and fellows who have served as Silver Scripts preceptors: Neal Benedict, Robert Berringer, Roberta Farrah, Heather Johnson, Trish Klatt, Meredith Rose, Karen Steinmetz Pater, Maria Yaramus; residents Shara Elrod, Jonathan Ference, Lauren Fields, Gladys Garcia, Stephanie Harriman, Maria Osborne, Heather Sakley, Christina Schober, Tina Scipio (fellow), Christin Snyder, Margie Snyder (resident/fellow), Katie Sullivan, and Lauren Veltry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hepler CD, Strand L. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Law 108-13. The Medicare Prescription, Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003. HR 1. December 8, 2003. http://www.cms.gov/MMAUpdate/downloads/PL108-173summary.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2011.

- 3.McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode JV, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management and pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47(5):620–628. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.06129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Sound medication therapy management programs, version 2.0 with validation study. J Managed Care Pharm. 2008;14(1):S2–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacIntosh D, Weiser C, WAssini A, Reddick J, Scovis N, Guy M, Boesen K. Attitudes toward and factors affecting implementation of medication therapy management services by community pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(1):26–30. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lounsbery JL, Green CG, Bennett MS, Pedersen CA. Evaluation of pharmacists’ barriers to the implementation of medication therapy management services. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49(1):51–58. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.017158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education; Chicago, IL: 2006. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy degree: effective July 1, 2007. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Pharmacists Association and National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication therapy management in pharmacy practice: core elements of an MTM service model (version 2.0) J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(3):341–353. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.08514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rickles NM, Tieu P, Myers L, Galal S, Chung V. The impact of a standardized patient program on student learning of communication skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(1):Article 4. doi: 10.5688/aj730104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolb DA. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland RW, Nimmo CM. Transitions, part 1: beyond pharmaceutical care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56(17):1758–1764. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.17.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rovers J, Miller MJ, Koenigsfeld C, Haack S, Hegge K, McCleeary E. A guided interview process to improve student pharmacists’ identification of drug therapy problems. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):Article 16. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan-Hewitt W, Austin Z. Pharmacy schools as expert communities of practice? A proposal to radically restructure pharmacy education to optimize learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3):Article 54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(6):749–756. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]