Abstract

Clinical pharmacy services necessitate appropriately trained pharmacists. Postgraduate year one (PGY1) community pharmacy residency programs (CPRPs) provide advanced training for pharmacists to provide multiple patient care services in the community setting. These programs provide an avenue to translate innovative ideas and services into clinical practice. In this paper, we describe the history and current status of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs, including an analysis of the typical settings and services offered. Specific information on the trends of community programs compared with other PGY1 pharmacy residencies is also discussed. The information presented in this paper is intended to encourage discussion regarding the need for increasing the capacity of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs.

Keywords: community pharmacy residency program, residency, community pharmacy, pharmacy services

INTRODUCTION

The American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) has called for pharmacists involved in the provision of “direct patient care” to have residency training by the year 2020.1 There are many logistical hurdles to implementing such a requirement, especially in the community pharmacy setting where the number of residency positions lags significantly behind pharmacy residency availability in health-system settings. There are approximately 5,800 registered hospitals in the United States, with over 2,000 health-system-based pharmacy residency positions.2,3 In contrast there are over 60,000 community pharmacies, but only 125 community pharmacy residency positions.4,5

Residency training is associated with progressive clinical practice.6,7 Within hospital pharmacies, for example, implementation of clinical services occurs more frequently when the director of pharmacy has an advanced degree and/or residency training.1,8 Just as residencies have been instrumental in the movement to integrate clinical pharmacy services into hospital and health-system settings, more residency programs in the community pharmacy arena may be transformative to the way services are delivered in that setting as well.9 Pharmacists in the community setting are among the most accessible of healthcare professionals. As such, they have tremendous opportunities to improve health outcomes for patients and to facilitate the patient-centered model of care long advocated within the profession.1,10-13

The objective of this paper is to promote the ongoing discussion of community pharmacy residency programs by reviewing the published literature related to the inception and growth of these programs over time. This paper also provides a snapshot of the community pharmacy residency landscape in the United States through an examination of existing programs and enrollment patterns.

HISTORICAL PROGRESSION

Pharmacy residencies in the United States trace their origins to the early postgraduate training opportunities for pharmacists that emerged in the 1930s. Initially called internships, these programs served primarily as management training for pharmacists in the hospital setting.14 By 1948, the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) had implemented standards for pharmacy internships, which evolved into a fully developed accreditation process by 1962. The new accreditation process resulted in a shift in nomenclature away from the term internships to residencies.15

The conceptual framework for community pharmacy residencies appeared decades after hospital residencies were established. Calls for implementation of community pharmacy residencies gained momentum in the early 1980s. The vision for these residencies was not uniform at the onset. Some saw residencies in community practice settings primarily as a means of strengthening the clinical skills of new graduates and thus improving the quality of pharmacy services.16 Others placed priority on instilling the necessary skills to own and operate an independent pharmacy business.17 During the 1982 American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Annual Meeting in Las Vegas, the APhA Academy of Pharmacy Practice's Section on Clinical Practice held an open forum on the topic of community residencies that examined the logistical and practical aspects of implementing residency programs in the community setting.18 Directors from the primary care residency program at the University of Maryland and the “mini-residency” for community pharmacists at the University of California (a 9-month, part-time training program) gave presentations.19 A key point of discussion during the forum centered on which aspects of pharmacy residencies in primary care, ambulatory care, and family practice were translatable to the community setting.

Citing a growing need for expertise and skill in community pharmacy practice, Sasich formalized a call to action in 1983 with a proposal for a residency program in the community setting, accompanied by suggested accreditation standards for such a residency.20 A response to that call came in 1984 when Downs and Knowlton formed a collaboration between the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science and Amherst Pharmacy of Lumberton, New Jersey, to develop a residency “designed to train the recent graduate in all aspects of community practice including pharmacy management, community involvement, community health programs, clinical practice, teaching and research.”16 The primary goals and expected competencies of this first community residency program were to prepare pharmacists for pharmacy ownership and a “patient-oriented approach to practice.”21

In 1986, APhA started the community pharmacy residency program initiative, which has served as the backbone for PGY1 community residency development. This was accompanied by a publication of programmatic essentials for community pharmacy residencies.9 These guidelines focused on outlining objectives for PGY1 community pharmacy residency skill development in the areas of management, drug distribution, clinical services, drug informatics, home health care, and long-term care.22 Other essential elements included residency director requirements and resident selection criteria.

While a practice management component has been retained in the curriculum for PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs, emphasis has gradually shifted to patient care, comparable to the transition from a managerial to a clinical training emphasis within health-system residencies.23-25 In 1997, APhA updated their original PGY1 community pharmacy residency program guidelines to reflect the increased emphasis on patient care and the revised guidelines were used as a basis for the first APhA-ASHP Community Pharmacy Residency Accreditation Standards, adopted in 1999.9

The adoption of an accreditation standard represented an important step in the development of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs. Accreditation led to initial and ongoing program development, stronger perceptions of the value of community pharmacy residencies by students and employers, and eligibility for pharmacy students seeking these residencies to participate in the Residency Match Program.26

Growth of Community Pharmacy Residency Programs

Hospital-based residencies have grown at a relatively rapid rate. In 1985, ASHP reported 184 accredited hospital residency programs.14 By 2000, this number had increased to 547 programs.27 In contrast, PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs experienced relatively slower growth from their inception in the 1980s, with only 26 active programs established by 2000.5 Narducci attributes the slower growth of community residencies to their not being perceived “as part of the mainstream of the clinical pharmacy movement.”28

In the early 2000s, a confluence of factors led to sudden growth in the number of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs. Between 1999 and 2001, the number of available positions nearly tripled.9 Unterwagner and colleagues attribute this surge in community pharmacy residencies to 3 key factors: a more favorable environment for clinical services in community settings; increased buy-in from colleges and schools of pharmacy in the development of community pharmacy experiential sites; and substantial funding for PGY1 residency programs from the Institute for the Advancement of Community Pharmacy (IACP).9 In June 2000, IACP announced the availability of $900,000 in grant funds to increase the number of community pharmacy residencies nationwide.29 The grants supported the establishment of 45 community pharmacy residency positions over a period of 6 years.

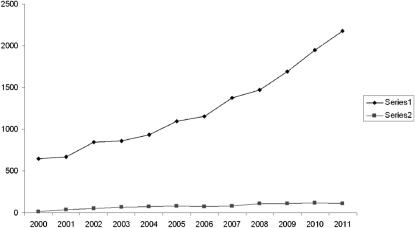

Once IACP's funding period had lapsed, growth of PGY1 community residency positions slowed (Figure 1). Trending data shows that the number of PGY1 community residency positions continues to increase, although growth does not match the rate of increase in PGY1 pharmacy residencies in general. An analysis of the growth rate of community programs (rather than positions) paints a picture of more consistent growth. Accredited PGY1 community pharmacy practice residencies expressed as a percentage of total PGY1 pharmacy residency programs remained at 8% between 2005 and 2010.5,28 This discrepancy can be explained by noting that community pharmacy residency programs usually have 1 resident per site, while hospital-based residency programs typically have 2 residents per site.30

Figure 1.

Growth of accredited community and total PGY1 residencies, 2000-2011(Series 1 = total PGY1 residency positions; Series 2 = community PGY1 residency positions).5,27,35

Schommer and colleagues examined the barriers to PGY1 community pharmacy residency program expansion and development by surveying colleges and schools of pharmacy and community pharmacy practice sites.31 Three key barriers facing residencies in the community were cited: difficulty in securing qualified program directors, insufficient program-generated revenue, and costs associated with residents’ salary. Thus, funding continues to be identified as one impediment to the growth of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs. Unlike hospital-based pharmacy residencies, federal funds through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are not available to residencies in community settings.32,33

TRENDS IN RESIDENCY DEMAND

An increasing number of applicants are competing for postgraduate pharmacy residency positions on an annual basis. While the pool of available residencies has expanded, it has not kept pace with demand as illustrated by Residency Matching Program statistics, which showed increased residency applicants, increased position fill rates, and increased numbers of students who failed to match with a residency program in 2009-2010.2 The number of PGY1 applicants in 2009-2010 was a 16% increase from the residency data reported in 2008-2009 and the number in 2010-2011 increased another 11%.2,34,35

Residency applicants who do not match with a program have an opportunity to apply for unfilled residency programs. The result of the “scramble,” as it is termed, is that many additional residency positions are filled. While it is challenging to accurately determine the number of students who are unable to place in a residency position after the scramble, it can be approximated by the gap between total unmatched applicants and total unmatched positions. In recent years, the number of students unable to secure a residency has increased. In 2007, the gap between unmatched positions and unmatched applicants was 288.34 By 2010, the gap had widened to 964. The gap remained steady at 954 in 2011.35

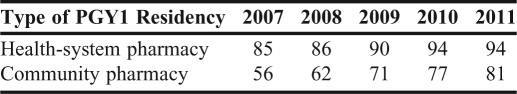

A requirement for accredited community pharmacy residencies to participate in the Residency Matching Program was implemented in 2007.36 Match rates are important in that they reflect the respective interests of both parties involved: applicants and programs. A match signifies a mutual deliberate choice between candidates and programs. Match rates for PGY1 community pharmacy residencies between 2007 and 2010 are compared with the rates from total PGY1 aggregate data from all other residencies in Table 1. As noted previously, these figures do not reflect the actual residency fill rates as they do not take into account positions filled during the “scramble.” It does, however, point to general trends. There has been an upward trend in match rates for both PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs and PGY1 residencies in general, but match rates for health-system residencies have been 13%-29% higher than PGY1 community pharmacy residency match rates since 2007.27,35 Further research is needed to assess the discrepancy in match rates between these 2 pharmacy settings, including students’ perceptions regarding the nature and value of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs.

Table 1.

Match Rates for the First-Year Postgradaute (PGY1) Pharmacy Residencies27,35

PROFILE OF PGY1 COMMUNITY RESIDENCIES IN 2010

There were 73 community pharmacy residency programs in 2010 and 125 residency positions. Sixty-three of these programs were accredited or in the process of accreditation. The programs are almost equally distributed among chain and independent pharmacies and some university-based programs have practice sites at both chain and independent pharmacies.30 PGY1 community pharmacy residencies also have a presence in less traditional community pharmacy settings such as outpatient health-system pharmacies and community clinics.

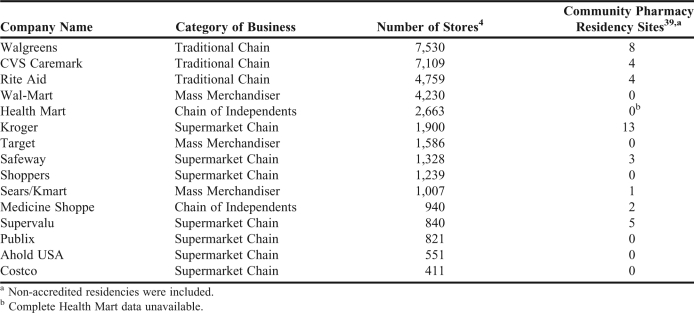

In a 2011 ASHP survey of residency stakeholders, a majority of respondents felt that participation of chain pharmacies is key to increasing community pharmacy residency positions.37 Among the top 15 retail pharmacy corporations in the United States, 8 have at least 1 community residency site (Table 2). Total capacity is limited to 40 residency positions among nearly 37,000 stores. Furthermore, the number of residencies among these chain pharmacies does not seem to be correlated with the number of stores.38 Kroger, for example, lists the most residency positions (13, subsidiary companies inclusive) despite ranking sixth in number of stores.39

Table 2.

Community Residencies in Largest US Pharmacy Corporations

Academic pharmacy plays a critical role in the administration of PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs. Residents often have academic responsibilities such as precepting students and teaching at an affiliated college or school of pharmacy. The majority of community pharmacy residency programs (85%) are associated with a college or school of pharmacy.5 In 2009, 40% of colleges and schools of pharmacy were affiliated with a PGY1 community pharmacy residency programand many feature robust programs with multiple practice sites.31 The University of Iowa College of Pharmacy currently has the most with 7 community pharmacy residency sites.39

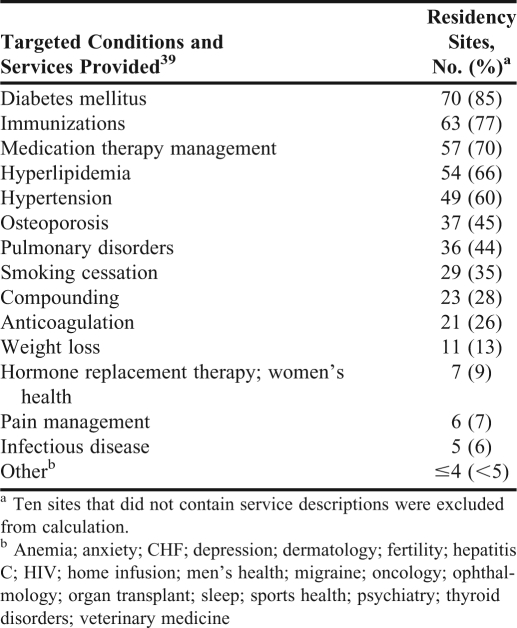

Because PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs have been cited as a way to promote the integration of clinical services into practice, the services offered by established residencies should be characterized. Table 3 includes a description of self-reported disease state targets and clinical services offered by US community pharmacy residency programs.40 There are limitations associated with this data, ie, the site descriptions are self-reported, may not be current, and may not represent a comprehensive listing of all current programs; however, they do provide insight into the general trends of services offered and disease states targeted. The most commonly reported clinical services offered are immunizations (77%), medication therapy management (MTM) (70%), and smoking cessation services (35%), while the most frequently reported disease states targeted included diabetes (85%), hyperlipidemia (66%), and hypertension (60%). Many sites had unique features. For example, some listed human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis as targeted disease states, whereas others focused on compounding or pain management. The variety of services offered and disease state focuses may allow students interested in PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs a variety of options to choose from based on their career interests.

Table 3.

Targeted Conditions and Services Offered at Community Pharmacy Residency Sites

Community pharmacies that have PGY1 residency programs are frequently associated with innovation. Kerr Drug, for example, has 10 community residency positions among their 90 stores.39 Services offered include pharmacogenomics counseling, preventive screenings, disease state management programs in diabetes and asthma, and wellness programs related to smoking cessation and weight loss.41 Kerr Drug was the largest provider of MTM services by volume from 2008-2010 and provision of these services is in part linked to Kerr Drug's residency programs.42

THE OUTLOOK FOR COMMUNITY RESIDENCIES

Several factors contribute to the favorable environment for continued growth of community pharmacy residencies. The National Association of Chain Drugs Stores (NACDS) Foundation announced in December 2010 the availability of $1,500,000 in grants to be awarded to nonprofit colleges and schools of pharmacy interested in partnering with independent or chain community pharmacies to create new or expand existing PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs.43 Comparable to the IACP grants of the early 2000s, these awards focus on lowering the cost barriers associated with program start up and expansion. The NACDS Foundation will award individual grants totaling $50,000 paid out over 3 years, with a goal of increasing PGY1 community pharmacy residency program nationwide by 25%.43

The atmosphere within the profession is also favorable for community pharmacy residency program expansion. Healthcare reform has created a variety of new opportunities for pharmacists to take on an expanded role in providing patient care services. Academicians and pharmacy professional associations are attributing increased significance to postgraduate training, and the profession has outlined a vision for pharmacy practice that positions pharmacists as the “…health care professionals responsible for providing patient care that ensures optimal medication therapy outcomes.”1,7,44 New opportunities for expanded roles may increase the demand for residency-trained pharmacists in the community setting.

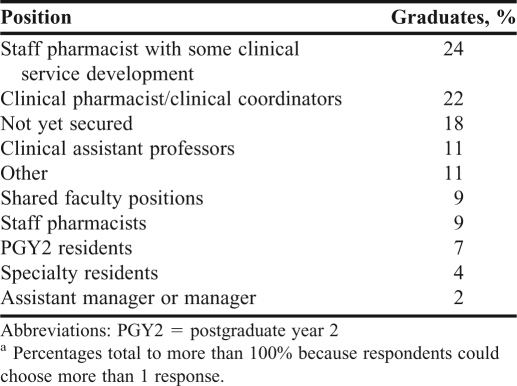

Similarly, demand for residencies continues to exceed the supply of available positions. While the recent economic recession may be partially responsible for this phenomenon as graduates are seeking to gain a competitive edge in the tightened job market, growth in demand actually predates the economic downturn of the late 2000s.2 Increasing demand may be attributed to the benefits reported from residency training. Pharmacists who complete a residency are more likely to report higher satisfaction with their employment than their counterparts without postgraduate training (45% and 32.7%, respectively; p < 0.001).45 APhA reports that a 1-year residency may be equated as up to 3 to 5 years of practice experience.32 Community pharmacy residencies also may help pharmacists secure positions that focus on the provision of clinical services. Table 4 lists the wide range of entry positions pharmacists accepted after completing a community residency in 2010. The majority of community pharmacy residency program graduates accepted positions that had elements of clinical service provision, while only 9% accepted jobs as general staff pharmacists.46

Table 4.

Employment Data of 2010 Graduates of Community Pharmacy Residency Programs (n = 45)a,46

CONCLUSION

Since their emergence in the United States in the 1980s, community pharmacy residencies have served as a developmental platform for refining pharmacy graduates’ clinical and managerial skills, and also as a vehicle to introduce and sustain patient care services in the community setting. With significant gaps in care within the overburdened US healthcare system, expansion of clinical and educational services in the community represents an opportunity for the pharmacy profession.47,48

Expansion of residencies within the community pharmacy practice setting must remain at the forefront of the discussion surrounding pharmacy clinical service advancement. Community pharmacy has been billed as “the face of neighborhood healthcare.”49 With a preponderance of pharmacists practicing in the community setting, PGY1 community pharmacy residency programs have a transformative potential for the profession, and represent a key component of the paradigm shift focusing on the patient-centered model of care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are all affiliated with a program discussed in the paper, the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation Community Pharmacy Residency Expansion Project. Samuel F. Stolpe and Alex J. Adams are administrators and reviewers; Lynette R. Bradley-Baker, Anne L. Burns, and James A. Owen are reviewers of said program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy JE, Nappi JM, Bosso JA, et al. ACCP position statement. American College of Clinical Pharmacy's vision of the future: postgraduate pharmacy residency training as a prerequisite for direct patient care. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(5):722–733. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Health-systems Pharmacists. ASHP Resident Matching Program 2010. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-Match2010.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 3.American Hospital Association. Fast facts on U.S. hospitals. http://www.aha.org/aha/resource-center/Statistics-and-Studies/fast-facts.html. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 4.Miller L. National Association of Chain Drug Stores. Alexandria: Virginia; 2010-11. Chain pharmacy industry profile. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montuoro J. PGY1 community pharmacy residency open forum. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/PRC2011/Actual-Expansion-Community.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 6.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Why should I do a residency? http://www.ashp.org/s_ashp/docs/files/RTP_ASHPResidencyBrochure.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 7.Smith KM, Sorensen T, Connor KA, Dobesh PP, et al. Value of conducting pharmacy residency training—the organizational perspective. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(12):490–510. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raehl CL, Bond CA, Pitterle ME. Pharmaceutical services in U.S. hospitals in 1989. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49(2):323–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unterwagner WL, Zeolla MM, Burns AL. Training experiences of current and former community pharmacy residents, 1986-2000. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43(2):201–206. doi: 10.1331/108658003321480740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society of Health-systems Pharmacists. 2010 ASHP leadership agenda. http://www.ashp.org/menu/ABOUTUS/LeadershipAgenda.aspx. Accessed September 12, 2011.

- 11.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Integration of pharmacists’ clinical cervices in the patient-centered primary medical home. http://www.accp.com/docs/misc/pcmh_services.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 12.American Pharmacists Association. Pharmacy groups unveil findings, future of “project destiny” [press release] http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=15492. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 13.Roadmap to 2015: preparing competent pharmacists and pharmacy faculty for the future. Combined Report of the 2005-06 Argus Commission and the Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;(5):70. Article S5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Definitions of pharmacy residencies and fellowships. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44(5):1142–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bright DR, Adams AJ, Black CD, Powers MF. The mandatory residency dilemma: parallels to historical transitions in pharmacy education. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(11):1793–1799. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groves RE. Community residency: a student perspective. Am Pharm. 1983;NS23(5):24–25. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)31966-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downs GE, Knowlton CH, Trutt TA, Cusick JJ. Initiating a community pharmacy residency. Am Pharm. 1986;NS26(6):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)32998-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A residency in community pharmacy practice: is there a need? Am Pharm. 1983;NS23(5):18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiser TH. The University of Maryland Primary Care Residency Program. Am Pharm. 1983;23(5) doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)31965-1. 20-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasich LD. A proposal for a community pharmacy practice residency program. Am Pharm. 1983;NS23(5):25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0160-3450(16)31967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy DH. What's gained from a community residency: talking with Downs, Knowlton, and Cusick. Am Pharm. 1986;NS26(6):93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 22.APhA community pharmacy residency program: programmatic essentials. Am Pharm. 1986;NS26(4):34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott S, Constantine LM. Community pharmacy residency programs lend a fresh perspective to practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999;39(6):750–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Definitions of pharmacy residencies and fellowships. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1987;44(5):1142–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivey MF, Farber MS. Pharmacy residency training and pharmacy leadership: an important relationship. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68(1):73–76. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists. How to start a residency program. http://www.ashp.org/s_ashp/docs/files/RTP_HowStartResidencyPrgm.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 27.Teeters J, Apple A. American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists 2010 National Residency Preceptors Conference. Omni Shoreham Hotel; Washington, DC: Aug 2010. Preceptors reaching monumental heights. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narducci WA. Revised CPRP guidelines increase opportunities for postgraduate education in pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1998;38(4):436–439. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Institute for the Advancement of Community Pharmacy announces nearly $900,000 in grants to support new and existing community pharmacy residencies. PRNewswire. June 20, 2000 http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-62831904.html. Accessed August 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teeters J. The current landscape of pharmacy residency training. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/PRC2011/Current-Landscape.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 31.Schommer JC, Bonnarens JK, Brown LM, Goode JV. Value of community pharmacy residency programs: college of pharmacy and practice site perspectives. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50(3):72–88. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09151. (Wash) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burns AL. Residencies offer exciting opportunities in community practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999 Nov-Dec;39(6):748. (Wash) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nappi J. The role of residencies in the education continuum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(3) Article 58. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norris M. Residency growth in North Carolina. NC Pharm. 2010;90(4):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists. ASHP residency matching program for positions beginning in 2011. http://www.natmatch.com/ashprmp/reglink.htm. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 36.American Society of Health-systems Pharmacists. Pharmacy residency training update 2006 ASHP Midyear Clinical Meeting. http://www.ashp.org/s_ashp/docs/files/RTP_MCMTownhall2006.ppt. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 37.American Society of Health-systems Pharmacists. Residency capacity survey results. http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/Residency-Capacity-Survey-Results.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 38.Annual report of retail pharmacy. Chain Drug Rev. 2010:32(14);52;61.

- 39.American Pharmacists Association. 2010-11 Postgraduate year one community residency program directory. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home2&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=21849. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 40.American Pharmacists Association. Community pharmacy residency programs. http://www.pharmacist.com/ResidencyLocator/ShowProgram.asp. Accessed August 11, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Walden G. Kerr Drug stretches horizons for Rx. http://www.chaindrugreview.com/inside-this-issue/news/11-23-2009/kerr-drug-stretches-horizons-for-rx. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 42.Kerr Drug recognized as leading chain in MTM. http://www.chaindrugreview.com/front-page/newsbreaks/kerr-drug-recognized-as-leading-chain-in-mtm. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 43.Shapiro L. NACDS. Foundation dedicates $1.5 million in grants for pharmacy residencies. Drug Topics. http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drugtopics/Pharmacy+News/NACDS-Foundation-dedicates-15-million-in-grants-fo/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/700562. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 44.AACP policies on postgraduate education and training. http://www.aacp.org/governance/COMMITTEES/professionalaffairs/Documents/AACPPoliciesonPostgraduateEducationandTraining.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2011.

- 45.Padiyara RS, Komperda KE. Effect of postgraduate training on job and career satisfaction among health-system pharmacists. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2010;67(13):1093–1100. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.American Pharmacists Association. 2009-10 PGY1 community pharmacy resident exit survey. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Residencies_Advanced_Training&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=18237. Accessed August 11, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Vanderveen RP. How to care for 30 million more patients. Wall Street Journal. July 19, 2010 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704113504575264584120959328.html. Accessed August 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shrank WH, Avorn J. Educating patients about their medications: the limitations and potential of written drug information. Health Affairs. 2007;26(3):731–740. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woldt J. Q&A: Anderson keeps NACDS focused on what matters. Chain Drug Rev. 2010;32(8):1–9. 26. [Google Scholar]