Abstract

There is increasing evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress may be integral to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heat shock protein (Hsp60) is a mitochondrial stress protein known to be induced under conditions of mitochondrial impairment. Although this intracellular protein is normally found in the mitochondrion, several studies have shown that this protein is also present in systemic circulation. In this study, we report the presence of elevated levels of Hsp60 in both saliva and serum of type 2 diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic controls. Hsp60 was detectable in the saliva of 10% of control and 93% of type 2 diabetic patients. Levels detected were in the range of 3–7 ng/ml in control and 3–75 ng/ml in type 2 diabetic patients. Serum Hsp60 levels in the range of 3–88 ng/ml were detected in 33% of control subjects, and levels in the range of 28–1,043 ng/ml were detected in 100% of type 2 diabetic patients. This is the first reporting of the presence of mitochondrial stress protein in salivary secretions. The serum Hsp60 levels were 16-fold higher compared to those in saliva, and there was a good positive correlation between salivary and serum Hsp60 levels (r = 0.55). While the exact mechanisms responsible for the secretion of Hsp60 into biological fluids such as saliva and blood are not yet known. The presence of this molecular marker of mitochondrial stress in saliva offers a non-invasive route to further investigate the biological functions of extracellular Hsp60 in type 2 diabetes mellitus and other conditions.

Keywords: Hsp60, Saliva, Mitochondria, Diabetes mellitus

Introduction

The extracellular location of heat shock proteins is becoming increasingly well documented. Heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), a nuclear-encoded protein found in the mitochondrial matrix is known to be induced under conditions of mitochondrial stress (Broadley and Hartl 2008; Martinus et al. 1996; Zhao et al. 2002). Interestingly, this stress protein is also known to have very strong immunogenic properties and has been shown to be present on the surface of mammalian cells (Pfister et al. 2005; Soltys and Gupta 1997) and also in systemic circulation in human subjects under both healthy and disease states. The presence of Hsp60 in serum of normal individuals and elevated levels in individual with borderline hypertension was first reported by Pockley et al. (1999). Circulating Hsp60 in healthy teenagers and a possible association with endothelial dysfunction has also been suggested (Halcox et al. 2005). Studies of 1sclerosis reporting a correlation between serum Hsp60 levels and arterial intima-media thickness suggested that circulating levels of Hsp60 is associated with vascular injury (Ellins et al. 2008; Pockley et al. 2003; Xu et al. 2000). Given the relationship documented between circulating Hsp60 levels and atherosclerosis and the recognition of mitochondrial impairment playing a central role in the pathogenesis of both types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, it is not surprising to also see elevated levels of Hsp60 in both types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus patients (Imatoh et al. 2009; Shamaei-Tousi et al. 2006). Although the significance of having elevated Hsp60 levels in diabetes mellitus is yet to be determined. The ability of Hsp60 to act as an immunogen as well as its ability to activate immune cells such as macrophages and vascular endothelial cells suggests that this molecule could be a key molecular marker of the progression and vascular complications of diabetes.

Interestingly, heat shock proteins have also been shown to be present in human saliva (Fábián et al. 2003, 2004; Fortes and Whitham 2011). The presence of Hsp70 in human saliva prompted us to investigate if the mitochondrial stress protein Hsp60 could also be detected in human saliva. The aim of this study was to investigate salivary levels of Hsp60 and to see how these levels correlated with serum Hsp60 levels using an ELISA procedure. The study groups consisted of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients (N = 41) and non-diabetic healthy individuals (N = 40).

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

Subjects were recruited from the Waikato Regional Diabetes Clinic, Hamilton, New Zealand. Non-diabetic partners of subjects were used as controls. Inclusion criteria used were as follows: (1) Patients required to have a non-diabetic partner (or equivalent in terms of age/environment) to be included in the study. (2) To help prevent selecting patients who may have unknown cardiovascular disease, only recently (≤1 year) diagnosed type 2 diabetics were selected. Patients with longstanding diabetes were more likely to have significant complications such atherosclerotic disease which has been shown to influence HSP60 plasma levels. Exclusion criteria for both control and test subjects were as follows: (1) Active bacterial or viral infection, (2) known cardiovascular disease, (3) known inflammatory disease, (4) known malignancy. Other studies on HSPs have attempted to control for environmental stresses by asking patients to refrain from exertion, smoking, caffeine and alcohol for 2–24 h and not taking samples from subjects with active bacterial or viral infection or other illness. Similar restrictions were applied to our participants.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Waikato Hospital Human Ethics Committee.

Blood and saliva samples were obtained from 40 control subjects (22 male, 18 female), median age 42 (range 18–66); from 41 type 2 diabetic subjects (23 male, 18 female), median age 53 (range 28–79). Blood samples were collected by venipuncture. Plasma was collected following blood centrifugation at 1,500×g at 4°C for 10 min and immediately frozen at −20°C. Unstimulated saliva samples were collected using a passive drool technique described by Oliver et al. (2008). The subjects were instructed to rinse their mouths with water first, and then allowed the saliva to passively accumulate (without spitting) in their mouth for 5 min, and finally transferred it into a collecting vessel. The samples were sterile-filtered to remove bacteria and mucosal cell contamination using 0.22 μm pore-size filters (Millipore, USA) and cleared by centrifugation (20,000×g, 4°C, 10 min). The supernatants were stored at −20°C until used.

Enzyme immunoassay for Hsp60

Nunc-Immuno™ 96-well plates were coated with a mouse anti-Hsp60 monoclonal antibody to human Hsp60 (LK-1; StressGen) in 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6), shacking 3 h and leaving overnight at 4°C (100 μl per well; 1 μl/ml). Coated plates were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS/T) using an automatic plate washer. Then, non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubation with 250 μl per well of PBS/T containing 5% skim milk powder and 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. After washing, 100 μl of the recombinant human Hsp60 at diluted 0–60 ng/ml or samples were added and the plates incubated for 2 h at room temperature with shacking. Plates were washed, and peroxidase activity in the samples was reduced by incubation with 250 μl per well 0.3% H2O2 for 1 h at room temperature with shacking. Plates were washed, and bound Hsp60 was detected by adding 100 μl rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp60 antibody (1:1000) in PBS/T. After 2 h incubation, plates were washed and incubated with 100 μl of goat anti-rabbit IgG link HRP (1:20,000) for 1 h with shaking. Binding of conjugated antibody was detected by adding 100 μl of TMB substrate for 5 min shacking and incubated in dark up to 20 min, then reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl 2M H2SO4. The resultant absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a plate reader. Each plasma and saliva sample was assayed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MINITAB16 with the Mann–Whitney test to compare the medians between the normal control and diabetic patient groups. T test was also used to analyse the results from two samples. A value p < 005 indicated statistical significance. The correlation between saliva and serum concentration of Hsp60 in diabetic patients were performed by Pearson correlation analysis.

Results and discussion

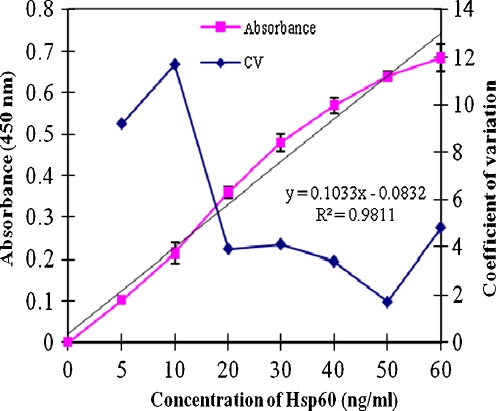

The objective of this study was to first determine if Hsp60 could be detected in human saliva using an ELISA procedure, and second, to compare the levels from saliva from control and type 2 diabetic patients and see if a correlation exists between salivary and serum levels. A representative standard curve for the Hsp60 assay was obtained first to determine the accuracy and sensitivity of the Hsp60 ELISA. The variability of the assay expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV) was less than 5% at concentrations of Hsp60 below 20 ng/ml, and the sensitivity of the assay, defined as the concentration that gives an absorbance twice that of the zero standard value, was 1.6 ng/ml (Fig. 1). This compares to an Hsp60 ELISA sensitivity of 27.4 ng/ml reported by Pockley et al. (1999).

Fig. 1.

Representative standard dose–response curve and precision profile for the Hsp60 ELISA. Error bar represents standard deviation (n = 6)

The inter-assay variability of the Hsp60 assay was 5.5 CV over six separate assays, each carried out in triplicate (Fig. 1).

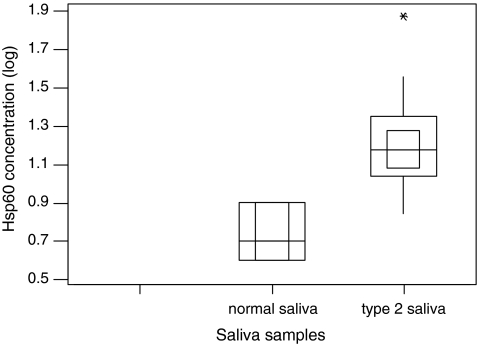

When saliva was analysed for the presence of Hsp60, 10% of control subjects and 93% of type 2 diabetic patients were shown to contain this mitochondrial-specific molecular stress protein. Levels detected were in the range of 3–7 ng/ml in control and 3–75 ng/ml in type 2 diabetic patients (Table 1). The salivary Hsp60 levels from type 2 diabetic patients were fourfold higher compared to those from control samples. Furthermore, there was a significant difference between the levels of Hsp60 detected in saliva from control and type 2 diabetic patients (p < 0.001). Figure 2 demonstrates the difference of Hsp60 presents in saliva in normal control (median 0.66 (log), interquartile range 0.621–0.903 (log)) and diabetes groups (median 1.18 (log), interquartile range 0.845–1.875 (log)). This is the first reporting of Hsp60 levels in salivary secretions. The source of the salivary Hsp60 is not yet known. It is unlikely to have arisen from bacterial contamination due to the sterile 0.2-μm filtration procedure used to treat the collected saliva prior to analysis and the specificity of the human anti-Hsp60 monoclonal antibody used in the ELISA which recognises epitopes between 383 and 447 of the human Hsp60 molecule does not cross-react with the bacterial homologues of Hsp60 (GroEL) (Boog et al. 1992). The salivary Hsp60 detected in this study may have arisen from passive transport via the salivary glands from blood serum, similar to other blood proteins such as albumin and blood group antigens (Gleeson et al. 1991). The possibility that some direct blood contamination might contribute to this salivary Hsp60 expression was unlikely as microscopic examination of the collected saliva did not show any signs of blood contamination (data not shown). Interestingly, diabetics are known to be at a higher risk of developing gingivitis and periodontal disease, and the possibility exists that the higher levels of Hsp60 observed in type 2 diabetic patients saliva could be a reflection of the state of their oral health.

Table 1.

Hsp60 concentration in saliva and serum

| Sample type | Number of samples | Percentage (%) of positive Hsp60 | Hsp60 (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal saliva | 40 | 10 | |

| Mean±SD | 4 ± 2 | ||

| (range) | (3–7) | ||

| Normal serum | 40 | 33 | |

| Mean±SD | 25 ± 25 | ||

| (range) | (3–88) | ||

| Type 2 saliva | 41 | 93 | |

| Mean±SD | 17 ± 13 | ||

| (range) | (5–75) | ||

| Type 2 serum | 41 | 100 | |

| Mean±SD | 277 ± 264 | ||

| (range) | (28–1,043) |

Fig. 2.

Hsp60 present in type 2 diabetes and normal saliva. The data with log transformation are presented as minimum and maximum (vertical line), interquartile range (outside square), median (horizontal line) and 95% confidence of the median (inner square)

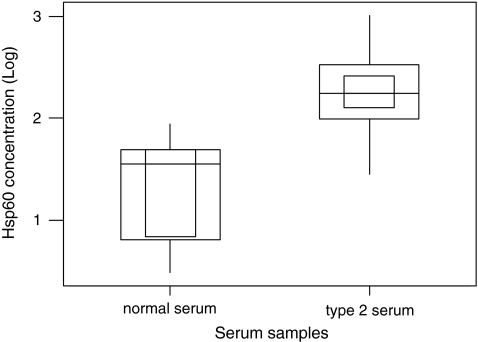

Serum Hsp60 levels were detected in 33% of control subjects and 100% of type 2 diabetic patients. Levels detected were in the range of 3–88 ng/ml in control and 28–1,043 ng/ml in type II diabetic patients (Table 1). There was also a significant difference between levels of Hsp60 found in serum of control and type 2 diabetic patients (p < 0.001). Figure 3 demonstrates the difference of Hsp60 presents in serum in normal control (median 1.56 (log), interquartile range 0.477–1.732 (log)) and diabetes groups (median 2.25 (log), interquartile range 1.447–1.732 (log)).

Fig. 3.

Hsp60 present in type 2 diabetes and normal serum. The data with log transformation are presented as minimum and maximum (vertical line), interquartile range (outside square), median (horizontal line) and 95% confidence of the median (inner square)

Although the levels of serum Hsp60 detected in this study were consistent with the range of values reported previously in the literature, the percentages of the cohort that had no measurable Hsp60 in serum varied considerably from the data published in the literature. For example, Xu and co-workers (2000) who assayed Hsp60 in sera from a large population of individuals in a prospective study of atherosclerosis reported that approximately one third of the sera had no measurable Hsp60, and Shamaei-Tousi et al. (2006) reported that Hsp60 was below the limit of assay detection in 46.9% of the sample. Such discrepancies might be due to the detection limits of the assays employed and also due to ethnic variations in the expression of Hsp60 in the population groups studied. It should be noted that despite a number of studies documenting the presence of Hsp60 in systemic circulation, the source of Hsp60 found in serum is not yet known. We suggest that it could be reflecting mitochondrial dysfunction in yet to be identified target cells, possibly endothelial cells given that stressing of such cells have been documented to lead to expression of Hsp60 on the plasma membrane (Xu et al. 1994). Secretion from such cells could possibly occur via exosomal-mediated transport similar to that documented for Hsp60 secretion from cardiac myocytes (Gupta and Knowlton 2007). Since Hsp60 at levels >10 μg/ml has been shown to be capable of activating human monocytes and vascular endothelial cells and modulate the activity of other cell populations (Maguire et al. 2005). The levels of Hsp60 documented in systemic circulation in this study and others in the literature could have important physiological consequences.

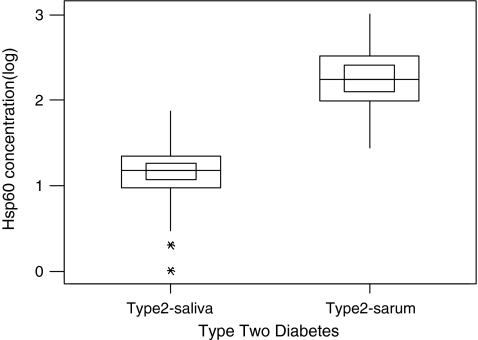

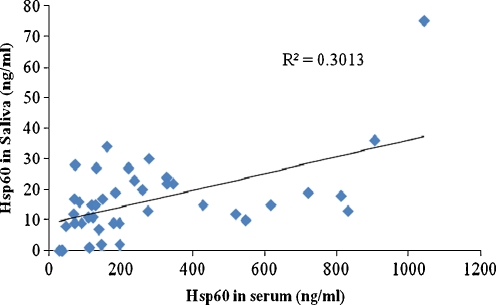

Interestingly, the serum Hsp60 levels were 16-fold higher compared to those in saliva (Fig. 4). A scatter plot of salivary Hsp60 levels and serum Hsp60 levels indicated a positive correlation between salivary and serum levels of Hsp60 (Fig. 5). The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to be 0.55, indicating a good correlation between salivary and serum concentration of Hsp60. These results are significantly different to those reported recently for the levels of Hsp72 in serum and saliva of human subjects subjected to exercise stress and caffeine supplementation (Fortes and Whitham 2011). This study showed that there was a fivefold increase in salivary Hsp72 levels compared to serum Hsp72 levels and that there was no correlation between the concentrations of salivary and plasma Hsp72. The reasons for this discrepancy between the two different heat shock proteins are not yet known. The differences in expression levels might be reflective of the distinct biological functions played by these molecular stress proteins.

Fig. 4.

Hsp60 present in saliva and serum in type 2 diabetes. The data with log transformation are presented as minimum and maximum (vertical line), interquartile range (outside square), median (horizontal line) and 95% confidence of the median (inner square)

Fig. 5.

Relationship of Hsp60 concentration between saliva and serum in type 2 diabetes. Serum concentration of Hsp60 (ng/ml) was plotted against Hsp60 in saliva in diabetes patients (n = 41). Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to be 0.55 with R2 = 0.3013

In conclusion, we have provided evidence for the presence of mitochondrial specific Hsp60 in human saliva with a good positive correlations between salivary and serum levels. This suggest that measuring Hsp60 levels non-invasively via salivary secretions could provide a novel avenue to further study the role of this stress protein in diabetes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mrs. A. Johnstone for her expert technical help during subject recruitment and saliva and blood collections at the Waikato Regional Diabetes Clinic.

References

- Boog C, Graeff-Meeder E, Lucassen M, Zee R, Voorhorst-Ogink M, Kooten P, Geuze H, Eden W. Two monoclonal antibodies generated against human hsp60 show reactivity with synovial membranes of patients with juvenile chronic arthritis. J Exp Med. 1992;175(6):1805–1810. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.6.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadley SA, Hartl FU. Mitochondrial stress signaling: a pathway unfolds. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellins ES-TA, Steptoe A, Donald A, O'Meagher S, Halcox J, Henderson B. The relationship between carotid stiffness and circulating levels of heat shock protein 60 in middle-aged men and women. J Hypertens. 2008;26(12):2389–2392. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328313918b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fábián TK, Gaspar J, Fejérdy L, Kaán B, Bálint M, Csermely P, Fejérdy P. Hsp70 is present in human saliva. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(1):BR62-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fábián TK, Tóth Z, Fejérdy L, Kaán B, Csermely P, Fejérdy P. Photo-acoustic stimulation increases the amount of 70 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) in human whole saliva. A pilot study. Int J Psychophysiol. 2004;52:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes M, Whitham M. Salivary Hsp72 does not track exercise stress and caffeine-stimulated plasma Hsp72 responses in humans. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2011;16:345–352. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0244-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson M, Dobson AJ, Firman DW, Cripps AW, Clancy RL, Wlodarczyk JH, Hensley MJ. The variability of immunoglobulins and albumin in salivary secretions of children. Scand J Immunol. 1991;33:533–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Knowlton AA. HSP60 trafficking in adult cardiac myocytes: role of the exosomal pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H3052–H3056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01355.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcox JPJDJ, Shamaei-Tousi A, Henderson B, Steptoe A, Coates ARM, Singhal A, Lucas A. Circulating human heat shock protein 60 in the blood of healthy teenagers: a novel determinant of endothelial dysfunction and early vascular injury? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:e141–e142. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000185832.34992.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imatoh T, Sugie T, Miyazaki M, Tanihara S, Baba M, Momose Y, Uryu Y, Une H. Is heat shock protein 60 associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire M, Poole S, Coates ARM, Tormay P, Wheeler-Jones C, Henderson B. Comparative cell signalling activity of ultrapure recombinant chaperonin 60 proteins from prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Immunology. 2005;115:231–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinus RD, Garth GP, Webster TL, Cartwright P, Naylor DJ, Høj PB, Hoogenraad NJ. Selective induction of mitochondrial chaperones in response to loss of the mitochondrial genome. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0098h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver SJ, Laing SJ, Wilson S, Bilzon JLJ, Walsh NP. Saliva indices track hypohydration during 48 h of fluid restriction or combined fluid and energy restriction. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister G, Stroh CM, Perschinka H, Kind M, Knoflach M, Hinterdorfer P, Wick G. Detection of HSP60 on the membrane surface of stressed human endothelial cells by atomic force and confocal microscopy. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1587–1594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Bulmer J, Hanks BM, Wright BH. Identification of human heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) and anti-Hsp60 antibodies in the peripheral circulation of normal individuals. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1999;4(1):29–35. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1999)004<0029:IOHHSP>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Georgiades A, Thulin T, Faire U, Frostegard J. Serum heat shock protein 70 levels predict the development of atherosclerosis in subjects with established hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:235–238. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000086522.13672.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamaei-Tousi A, Stephens JW, Bin R, Cooper JA, Steptoe A, Coates ARM, Henderson B, Humphries SE. Association between plasma levels of heat shock protein 60 and cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1565–1570. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltys BJ, Gupta RS. Cell surface localization of the 60 kDa heat shock chaperonin protein (hsp60) in mammalian cells. Cell Biol Int. 1997;21:315–320. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1997.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Schett G, Seitz CS, Hu Y, Gupta RS, Wick G. Surface staining and cytotoxic activity of heat-shock protein 60 antibody in stressed aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1994;75:1078–1085. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Schett G, Perschinka H, Mayr M, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Willeit J, Kiechl S, Wick G. Serum soluble heat shock protein 60 is elevated in subjects with atherosclerosis in a general population. Circulation. 2000;102:14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Wang J, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2002;21:4411–4419. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]