Abstract

Earlier, we showed that the offspring from exceptionally long-lived families have a more favorable glucose metabolism when compared with controls. As chronic low-grade inflammation has been regarded as a strong risk factor for insulin resistance, we evaluated if and to what extent the favorable glucose metabolism in offspring from long-lived families could be explained by differences in subclinical inflammation, as estimated from circulating levels of C-reactive protein. We found no difference between the two groups in C-reactive protein levels or in the distribution of C-reactive protein haplotypes. However, among controls higher levels of C-reactive protein were related to higher glucose levels, whereas among offspring levels of C-reactive protein were unrelated to glucose levels. It is a limitation of the current study that its cross-sectional nature does not allow for assessment of cause–effect relationships. One possible interpretation of these data is that the offspring from long-lived families might be able to regulate glucose levels more tightly under conditions of low-grade inflammation. To test this hypothesis, our future research will be focused on assessing the robustness of insulin sensitivity in response to various challenges in offspring from long-lived families and controls.

Keywords: C-reactive protein, Insulin resistance, Humans, Longevity

Introduction

The association between chronic subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance has been well established (Shoelson et al. 2006). Insulin resistance in turn is regarded a strong risk factor for type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (Mcfarlane et al. 2001; Shen et al. 1988). Levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of systemic inflammation, are elevated in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance as well as in overt diabetes (Ford 1999; Temelkova-Kurktschiev et al. 2002), and increased levels of CRP are predictive for development of diabetes (Barzilay et al. 2001; Pradhan et al. 2001). Observational studies have shown a relation between elevated levels of CRP and elevated glucose levels in subjects without diabetes as well (Doi et al. 2005; Festa et al. 2002; Nakanishi et al. 2005).

In the Leiden Longevity Study, we have recruited exceptionally long-lived families based on proband siblings that both exhibit exceptional longevity. We also included the middle-aged offspring of the long-lived siblings and their partners as population-based controls. Earlier, we have shown that the offspring from these long-lived families have a lower prevalence of type 2 diabetes when compared with controls (Westendorp et al. 2009). Moreover, we demonstrated that after exclusion of diabetic patients the offspring from long-lived families had relatively lower fasted and non-fasted glucose levels as well as a higher glucose tolerance (Rozing et al. 2009; Rozing et al. 2010). The differences in glucose metabolism between offspring from long-lived families and controls could not be explained by differences in body composition or life style, such as smoking or physical activity.

In the current study, we sought to evaluate whether and to what extent the observed differences in glucose metabolism between the offspring from long-lived families and controls can be explained by differences in subclinical inflammation, as estimated from circulating levels of CRP. Therefore, we examined high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) serum levels as well as CRP genotypes and their influence on glucose regulation in the offspring from exceptionally long-lived families and controls.

Materials and methods

The Leiden Longevity Study

The recruitment of 421 families in the Leiden Longevity Study has been described before (Schoenmaker et al. 2006). A short outline is provided here. Families were recruited if at least two long-lived siblings were alive and fulfilled the age criterion of 89 years or older for males and 91 years or older for females. There were no selection criteria on health or demographic characteristics. For 2,415 offspring of long-lived siblings and their partners as population controls, non-fasting serum samples were taken at baseline for the determination of endocrine and metabolic parameters. Additional information was collected from the generation of offspring and controls, including self-reported information on life style, information on medical history from the participants’ treating physicians, and information on medication use from the participants’ pharmacists. Subjects with hsCRP levels higher than 10.0 mg/L were excluded from the study (68 offspring (4.6%) and 31 controls (4.9%)) as were subjects with diabetes (65 offspring (4.4%) and 53 controls (8.3%)). Subjects were regarded as having diabetes if they had non-fasted glucose levels >11.0 mmol/L, a previous medical history of diabetes and/or used glucose lowering agents. In 84 subjects (61 offspring and 23 controls), data on hsCRP and/or glucose were not available.

CRP genotypes

Three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were selected that associate with serum CRP levels: rs1205 (positioned in 3′UTR, alleles C/T), Rs1800947 (positioned in Codon 184, alleles G/C) and Rs1417938 (positioned in intron 1, alleles T/A). Genotyping of the SNPs was performed using Sequenom MassARRAY iPLEX®Gold. The high iPLEX primer design was performed by entering the sequences encompassing each polymorphism into SpectroDESIGNER provided by Sequenom®, Inc. (CA, USA). The high plex reaction protocol was used (www.sequenom.com/iplex). The average genotype call rate for genotyped SNPs was 96.3%, and the average concordance rate was 99.7% among 4% duplicated control samples. All SNPs were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p ≥ 0.05)

Plasma parameters

All serum measurements were performed with fully automated equipment. Insulin was measured on the Immulite 2500 Analyzer from Diagnostic Products Corporation (Los Angeles, CA, USA) using a solid-phase, enzyme-labeled chemiluminescent immunometric assay, according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For glucose and hsCRP, the Hitachi Modular P 800 from Roche, Almere, the Netherlands was applied. CV’s of all measurements were below 5%.

Statistical analysis

The program haploview was used to estimate allele frequencies, test the consistency of genotype frequencies at each SNP locus with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and estimate and plot pair wise LD between the examined SNPs. Haplotypes and haplotype frequencies were estimated using the SNPHAP software. The posterior probabilities of haplotypes <95% were excluded from the analyses (61 offspring and 24 controls).

Distributions of continuous variables were examined for normality and serum insulin levels and hsCRP levels were logarithmically transformed prior to analyses. Differences in age between the groups of offspring and controls were tested using a Mann–Whitney rank sum test. Differences in sex distribution between the groups of offspring and controls were calculated using a Chi-square test. Geometric means (with 95% confidence intervals) are reported for transformed variables. Associations between serum levels as well as associations between CRP haplotypes and serum levels were tested using a linear mixed model with a random sibship effect to model correlation of sibling data. Age, sex, body mass index, use of lipid-lowering agents, and current smoking were regarded as potential confounders in this association and were included in the analyses. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences program for Windows, version 16.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

The principal features of the study groups, both without diabetes, are displayed in Table 1. The proportion of males was slightly higher in the group of offspring than in the group of controls. Body mass index was similar between the two groups (p = 0.57). Non-fasted glucose levels were lower in the group of offspring when compared with the group of controls (p = 0.001), while non-fasted insulin levels did not differ (p = 0.16). We did not observe a difference in serum levels of hsCRP between the two groups. Also after adjustment for the potential confounders age, sex, body mass index, use of lipid-lowering agents, and current smoking, no difference in hsCRP levels was observed between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Offspring | Controls | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (N) | 1,479 | 635 | |

| Male sex (N, %) | 691 (46.7) | 264 (41.6) | 0.032 |

| Age in year (median (interquartile range)) | 59.1 (54.9–64.0) | 58.7 (53.8–63.6) | 0.078 |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 (mean, 95% CI)a | 25.3 (25.0–25.5) | 25.4 (25.1–25.7) | 0.57 |

| Lipid-lowering agent (N, %) | 87 (5.9) | 45 (7.1) | 0.33 |

| Currently smoking | 167 (13.2) | 78 (14.0) | 0.66 |

| Insulin in μ IU/L (mean, 95% CI) | 15.7 (14.9–16.4) | 16.6 (15.5–17.7) | 0.16 |

| Glucose in mmol/L (mean, 95% CI) | 5.70 (5.64–5.77) | 5.90 (5.81–5.99) | 0.001 |

| HsCRP in mg/dL (mean, 95% CI) | |||

| Adjusted for sex and age (model 1) | 1.21 (1.15–1.28) | 1.25 (1.16{1.34) | 0.54 |

| Model 1 and body mass index | 1.20 (1.32–1.26) | 1.23 (1.15–1.32) | 0.56 |

| Model 1 and lipid-lowering agents | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) | 0.48 |

| Model 1 and current smoking statusb | 1.30 (1.21–1.40) | 1.34 (1.23–1.46) | 0.53 |

| Model 1 and body mass index and lipid-lowering agents and current smoking status | 1.11 (1.01–1.23) | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | 0.54 |

Results for insulin and hsC-reactive protein (hsCRP) are presented as estimated geometric means with 95% confidence intervals

95% CI 95% confidence interval

aData on body mass were available for 1,823 subjects (1,266 offspring and 557 partners). Results for body mass index were adjusted for age and sex

bData on current smoking status were available for 1,819 subjects (1,262 offspring and 557 partners). Results for insulin and glucose were adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index

Potentially, genetic variation could mask true differences in CRP levels between the two groups. To distinguish between constitutional and acquired levels of hsCRP, we performed a genetic analysis of haplotypes constructed from the common CRP variants rs1205, rs1800947, and rs1417938 that have previously been associated with serum CRP levels. For the present analyses we report the results of the four most common haplotypes (frequency >5%) that cumulatively account for 99.9% of the haplotypes. The relation between the four selected haplotypes and serum hsCRP levels is depicted in Table 2. All haplotypes correlated significantly with hsCRP levels. An increasing number of haplotypes 1 and 2 gave rise to higher hsCRP levels, whereas an increasing number of haplotypes 3 and 4 was related to a decrease in hsCRP serum levels. The change in hsCRP levels over the number of haplotypes was not different between offspring and controls.

Table 2.

Association between CRP haplotypes and serum hsCRP levels

| Haplotype | 0 copies (mean (95% CI)) | 1 copy (mean (95% CI)) | 2 copies (mean (95% CI)) | p value for trend | p value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HsCRP (mg/dL) | |||||

| 1 | 1.17 (1.09–1.24) | 1.25 (1.18–1.34) | 1.35 (1.20–1.51) | 0.015 | 0.87 |

| 2 | 1.13 (1.06–1.20) | 1.28 (1.20–1.36) | 1.45 (1.28–1.65) | <0.001 | 0.63 |

| 3 | 1.32 (1.24–1.40) | 1.14 (1.07–1.22) | 1.04 (0.89–1.22) | <0.001 | 0.18 |

| 4 | 1.27 (1.21–1.34) | 0.97 (0.87–1.09) | 0.52 (0.29–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.23 |

Results for serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) are given as estimated geometric means and 95% confidence intervals for number of haplotypes. Results were adjusted for sex, age, and study group (controls and offspring). p value for interaction was calculated for the difference between controls and offspring in the trend of hsCRP over increasing number of haplotypes

Next, we assessed if the distribution of CRP haplotypes was different between the two groups. In both the study groups haplotypes were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. No difference in the frequencies of CRP haplotypes was observed between the group of offspring and the group of controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

CRP haplotype structure and frequencies

| SNP allele | Frequency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype | rs1205 | rs1800947 | rs1417938 | Offspring | Controls | p value |

| 1 | T | G | T | 0.335 | 0.344 | 0.57 |

| 2 | T | G | A | 0.336 | 0.315 | 0.17 |

| 3 | C | G | T | 0.260 | 0.273 | 0.38 |

| 4 | C | C | T | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.94 |

Minor alleles are set in italics

SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism

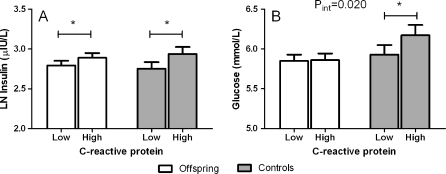

Since high levels of CRP have been associated with insulin resistance, we examined the association between serum levels of hsCRP and serum levels of non-fasted insulin as well as glucose for the group of offspring and the group of controls. Distributions of continuous variables were examined for normality and serum insulin levels and hsCRP levels were logarithmically transformed prior to analyses. Higher levels of hsCRP were consistently related to higher levels of insulin in both groups (Fig. 1a). In the group of offspring, one standard deviation increase in logarithmically transformed hsCRP (ln hsCRP) was associated with an increase in levels of logarithmically transformed insulin (ln insulin) of 0.08 (95% confidence interval, 0.04–0.13) μ IU/L (p < 0.001). In the group of controls, one standard deviation increase in ln hsCRP was associated with an increase in levels of ln serum insulin of 0.11 (95% confidence interval, 0.04–0.19) μ IU/L (p = 0.004). The relation between hsCRP and insulin was not different between the two groups (p value for interaction = 0.28). Next, we examined the relation between hsCRP and glucose in the two groups. Among offspring no significant relation was observed between one standard deviation increase in ln hsCRP and glucose (mmol/L): 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.08; p = 0.71) (Fig. 1b). In contrast among controls, one standard deviation increase in ln hsCRP was related with a 0.13 (0.02–0.24) mmol/L increase in serum glucose levels (p = 0.017). The association between hsCRP and glucose was significantly different in the group of controls when compared with the group of offspring (p value for interaction = 0.020).

Fig. 1.

Association between hsCRP levels and non-fasted serum insulin levels (a) and serum glucose levels (b) for offspring and controls. HsCRP levels were dichotomized into categories of low and high hsCRP levels based on the median value of hsCRP of the whole population (1.15 mg/dL). The analyses were adjusted for sex, age, lipid-lowering agents, BMI, and current smoking status. *p value lower than 0.05

If CRP haplotypes associate with CRP levels and CRP levels associate with markers of glucose metabolism, it could be expected that CRP haplotypes associate with markers of glucose metabolism. To tease out the causal relation between serum hsCRP and glucose metabolism we assessed the relationship between CRP haplotypes and serum levels of insulin as well as glucose (Table 4). In both groups, none of the haplotypes demonstrated an association with levels of serum insulin nor serum glucose.

Table 4.

Association between CRP haplotypes and serum glucose parameters

| Haplotype | 0 copies (mean (95% CI)) | 1 copy (mean (95% CI)) | 2 copies (mean (95% CI)) | p valuefor trend | p value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum insulin (μ IU/L) | |||||

| 1 | 16.1 (15.2–17.1) | 16.2 (15.3–17.2) | 16.9 (15.2–18.7) | 0.54 | 0.68 |

| 2 | 16.4 (15.5–17.4) | 16.0 (15.1–17.0) | 16.6 (14.8–18.7) | 0.84 | 0.15 |

| 3 | 16.4 (15.5–17.2) | 16.5 (15.5–17.5) | 14.4 (12.4–16.6) | 0.09 | 0.23 |

| 4 | 16.1 (15.5–16.9) | 17.3 (15.6–19.2) | 11.9 (6.57–21.6) | 0.41 | 0.83 |

| Serum glucose (mmol/L) | |||||

| 1 | 5.80 (5.72–5.87) | 5.82 (5.74–5.89) | 5.83 (5.68–5.97) | 0.66 | 0.49 |

| 2 | 5.80 (5.73–5.88) | 5.79 (5.71–5.87) | 5.92 (5.76–6.07) | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| 3 | 5.84 (5.77–5.91) | 5.79 (5.71–5.87) | 5.65 (5.46–5.85) | 0.09 | 0.40 |

| 4 | 5.80 (5.74–5.86) | 5.88 (5.74–6.02) | 5.39 (4.67–6.11) | 0.57 | 0.18 |

Results for serum insulin are given as estimated geometric means and 95% confidence intervals for number of haplotypes. Results for glucose are given as estimated means and 95% confidence intervals for number of haplotypes. Results were adjusted for sex, age, and study group (controls and offspring). p value for interaction was calculated for the difference between controls and offspring in the trend of insulin or glucose over increasing number of haplotypes

Discussion

Earlier it has been demonstrated that the offspring from exceptionally long-lived families have a more favorable glucose metabolism when compared with population-based controls (Rozing et al. 2009; Rozing et al. 2010). In the present study, we show that this difference in glucose metabolism could not be explained by current differences in subclinical inflammation, as estimated from serum levels of hsCRP. We did not find a difference in the levels of hsCRP between the group of offspring from long-lived families and the group of environmentally matched controls, nor in the frequencies of common genetic CRP variants and haplotypes. All CRP haplotypes correlated significantly with hsCRP levels, however no association was found between CRP haplotypes and insulin or glucose levels. We observed a distinct association between levels of hsCRP and levels of glucose in the two groups: in the group of controls increasing levels of hsCRP were associated with higher non-fasted glucose levels, whereas in the group of offspring this relation was absent.

The regulation of CRP levels via the paracrine effects of adipokines is well understood and the lack of difference between the group of offspring and controls in hsCRP levels is in line with our earlier observation that there were no significant differences in percentage of body fat or BMI between the groups (Rozing et al. 2010). Despite the absence of differences in BMI or percentage of body fat, we earlier observed a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the subgroups of offspring compared with controls for which data on metabolic syndrome were available (Rozing et al. 2010) The metabolic syndrome is a combination of cardiovascular risk factors for which the dominant underlying factor appears to be insulin resistance (Hanley et al. 2002). A chronic subclinical inflammatory state is considered a crucial factor in the development of insulin resistance (Temelkova-Kurktschiev et al. 2002; Spranger et al. 2003). In accordance, insulin resistance has been shown to correspond closely with elevated levels of inflammatory markers as CRP (Festa et al. 2000; Yudkin et al. 1999). It is a limitation of the current study that its cross-sectional nature does not allow for assessment of cause–effect relationships. One possible interpretation of the current observation that the difference in glucose levels reported earlier for offspring of long-lived families compared with controls is mostly manifested in the presence of high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP is that the offspring from long-lived families might be able to regulate glucose levels more tightly under conditions of low-grade inflammation. According to this hypothesis, subjects from long-lived families would be protected by their robust insulin sensitivity against the effects of low-grade inflammation and concomitant morbidity, such as for example metabolic syndrome. Alternatively, CRP or other factors associated with high CRP levels might be causal in the observed difference in glucose levels between groups in the presence of high CRP levels.

During inflammation, acute-phase reactants and pro-inflammatory cytokines are thought to induce a hypermetabolic state. This hypermetabolic state, which is aimed at mobilizing energy to support immune function and tissue repair, is characterized by an accelerated gluconeogenesis (Mizock 1995) as well as induced insulin resistance resulting in elevated glucose levels (Taniguchi et al. 2006) (Fig. 2a). Preserved insulin action in the offspring may allow for disposal of the excess glucose and/or reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis, thereby abolishing the inflammatory induced hyperglycemia (Fig. 2b). Hypothetically, a favorable balance between insulin-sensitizing and diabetogenic components underlies this phenomenon. Multiple endogenous diabetogenic components and insulin-sensitizing factors have been identified, as for example IL-6, TNF-α, PAI-1, and leptin on the one hand, and adiponectin on the other hand (Arai et al. 2009). Our future research will focus on unraveling the specific mechanisms of the robust glucose metabolism in offspring from long-lived families.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of inflammatory induced hyperglycemia. The inflammatory state is characterized by an accelerated hepatic gluconeogenesis as well as induced peripheral insulin resistance leading to hyperglycemia (a). Preserved insulin action in the offspring from long-lived families presumably allows for disposal of excess glucose and/or reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis, thereby abolishing the inflammatory induced hyperglycemia (b)

The absence of fasted samples has precluded homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. The absence of fasted samples for this relatively large cohort of the Leiden Longevity Study is a limitation of the current study. However, although uncontrolled, non-fasted samples reflect everyday variations in circulating concentration of insulin and glucose and may allow for detection of differences in glucose handling between groups across a physiologically relevant spectrum of insulin and glucose concentrations.

In conclusion, we found that the difference in non-fasted glucose levels reported earlier between groups of offspring from long-lived families and controls is most pronounced in the presence of high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP. It is a limitation of the current study that its cross-sectional nature does not allow for assessment of cause–effect relationships. However, one possible interpretation of this observation is that, compared with controls, offspring from long-lived families might be able to regulate glucose levels more tightly under conditions of low-grade inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stella Trompet for her valuable assistance with the statistical analyses of the data. This study was supported by the Innovation Oriented Research Program on Genomics (SenterNovem; IGE01014 and IGE5007), the Centre for Medical Systems Biology (CMSB), the Netherlands Genomics Initiative/Netherlands Organization for scientific research (NGI/NWO; 05040202 and 050-060-810 (NCHA)), and the EU funded Network of Excellence Lifespan (FP6 036894).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Arai Y, Kojima T, Takayama M, Hirose N. The metabolic syndrome, IGF-1, and insulin action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;299:124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay JI, Abraham L, Heckbert SR, Cushman M, Kuller LH, Resnick HE, Tracy RP. The relation of markers of inflammation to the development of glucose disorders in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Diabetes. 2001;50:2384–2389. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi Y, Kiyohara Y, Kubo M, Tanizaki Y, Okubo K, Ninomiya T, Iwase M, Iida M. Relationship between C-reactive protein and glucose levels in community-dwelling subjects without diabetes: the Hisayama Study. Diab Care. 2005;28:1211–1213. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa A, D'agostino R, Jr, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Circulation. 2000;102:42–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festa A, D'agostino R, Jr, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. C-reactive protein is more strongly related to post-glucose load glucose than to fasting glucose in non-diabetic subjects; the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabet Med. 2002;19:939–943. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ES. Body mass index, diabetes, and C-reactive protein among U.S. adults. Diab Care. 1999;22:1971–1977. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley AJ, Karter AJ, Festa A, D'agostino R, Jr, Wagenknecht LE, Savage P, Tracy RP, Saad MF, Haffner S. Factor analysis of metabolic syndrome using directly measured insulin sensitivity: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes. 2002;51:2642–2647. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcfarlane SI, Banerji M, Sowers JR. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:713–718. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.2.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock BA. Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism during stress: a review of the literature. Am J Med. 1995;98:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N, Shiraishi T, Wada M. Association between fasting glucose and C-reactive protein in a Japanese population: the Minoh study. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing MP, Westendorp RG, Frolich M, de Craen AJ, Beekman M, Heijmans BT, Mooijaart SP, Blauw GJ, Slagboom PE, van Heemst D. Human insulin/IGF-1 and familial longevity at middle age. Aging (Albany, NY) 2009;1:714–722. doi: 10.18632/aging.100071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozing MP, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ, Frolich M, de Goeij MC, Heijmans BT, Beekman M, Wijsman CA, Mooijaart SP, Blauw GJ, Slagboom PE, van Heemst D. Favorable glucose tolerance and lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in offspring without diabetes mellitus of nonagenarian siblings: the Leiden longevity study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:564–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmaker M, de Craen AJ, Beekman M, de Meijer PH, Blauw GJ, Westendorp RG, Slagboom PE. Evidence of genetic enrichment for exceptional survival using a family approach: the Leiden Longevity Study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:79–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen DC, Shieh SM, Fuh MM, Wu DA, Chen YD, Reaven GM. Resistance to insulin-stimulated-glucose uptake in patients with hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;66:580–583. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-3-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger J, Kroke A, MOHLIG M, Hoffmann K, Bergmann MM, Ristow M, Boeing H, Pfeiffer AF. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes. 2003;52:812–817. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.3.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temelkova-Kurktschiev T, Siegert G, Bergmann S, Henkel E, Koehler C, Jaross W, Hanefeld M. Subclinical inflammation is strongly related to insulin resistance but not to impaired insulin secretion in a high risk population for diabetes. Metabolism. 2002;51:743–749. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.32804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp RG, van Heemst D, Rozing MP, Frolich M, Mooijaart SP, Blauw BJ, Beekman M, Heijmans BT, de Craen AJ, Slagboom PE (2009) Nonagenarian siblings and their offspring display lower risk of mortality and morbidity than sporadic nonagenarians: the Leiden Longevity Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1634–1637 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, Coppack SW. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:972–978. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.19.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]