Background: Epicardium-derived cells undergo EMT and differentiate into smooth muscle of the developing coronary vasculature. The role of Dicer in this process is unknown.

Results: Dicer mutants displayed impaired epicardial EMT, reduced epicardial cell proliferation, and differentiation into coronary smooth muscle cells.

Conclusion: Dicer is essential for epicardium development.

Significance: This represents the first evidence for the involvement of Dicer, and by implication miRNAs, in epicardial development.

Keywords: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal Transition, Heart Development, MicroRNA, Mouse, Smooth Muscle, Coronary Vasculature, Dicer, Epicardium

Abstract

The epicardium is a sheet of epithelial cells covering the heart during early cardiac development. In recent years, the epicardium has been identified as an important contributor to cardiovascular development, and epicardium-derived cells have the potential to differentiate into multiple cardiac cell lineages. Some epicardium-derived cells that undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and delaminate from the surface of the developing heart subsequently invade the myocardium and differentiate into vascular smooth muscle of the developing coronary vasculature. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have been implicated broadly in tissue patterning and development, including in the heart, but a role in epicardium is unknown. To examine the role of miRNAs during epicardial development, we conditionally deleted the miRNA-processing enzyme Dicer in the proepicardium using Gata5-Cre mice. Epicardial Dicer mutant mice are born in expected Mendelian ratios but die immediately after birth with profound cardiac defects, including impaired coronary vessel development. We found that loss of Dicer leads to impaired epicardial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and a reduction in epicardial cell proliferation and differentiation into coronary smooth muscle cells. These results demonstrate a critical role for Dicer, and by implication miRNAs, in murine epicardial development.

Introduction

The mature epicardium is derived from a transient embryonic structure called the proepicardium, which is located anterior to the septum transversum and ventral to the sinus venosus (1). Proepicardium is composed of multipotent mesothelial progenitor cells that migrate over the myocardial surface of the looping heart and form a continuous layer of epithelial cells by embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5)3 of mouse embryonic development. Subsequently, epicardium-derived progenitor cells (EPDCs) undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and contribute to various lineages, including fibroblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells (and perhaps endothelial cells and cardiac myocytes) within the developing heart (2–5). Manipulation of proepicardium in chick embryos either by blocking proepicardial cell migration or by mechanical excision or photoablation of proepicardium, has demonstrated an epicardial requirement for coronary vessel development (6, 7). Similar results were obtained in mouse by genetic deletion of genes expressed in the epicardium such as adhesion molecules (i.e. VCAM-1, α4-integrin, and etc.), transcription factors (i.e. Wt1), or signaling molecules (i.e. RXRα, β-catenin) (8). In addition to its role in cardiac development, the epicardium also regulates cardiac regeneration after injury in lower vertebrates (9, 10). In mammals, the regeneration potential of cardiac tissue is limited, but epicardium is activated and supports formation of new blood vessels by triggering differentiation of EPDCs into fibroblast, smooth muscles, and endothelial cells after myocardial infarction (11).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent a class of evolutionary conserved small (19–25 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs that modulate gene expression by inhibiting mRNA translation or stability and thereby regulates diverse developmental and physiological processes (12, 13). In vertebrates, hundreds of miRNAs have been identified with differential expression patterns that range from ubiquitous to highly tissue-specific. MicroRNAs can act individually or in clusters to regulate a wide range of developmental processes. A powerful method to investigate miRNA function in murine embryos and tissues is to genetically inactivate Dicer, an endoribonuclease that cleaves pre-miRNA to generate ∼22-nucleotide-long miRNA duplexes (14). These duplexes are normally incorporated into the miRNA-associated multiprotein RNA-induced silencing complex. Eventually, one strand of the miRNA is preferentially retained in this complex and becomes the mature miRNA, whereas the opposite/passenger strand is eliminated from the complex. The mature miRNA binds to the complementary sequences of 3′-UTR of the target mRNAs and modulates their expression either by translational silencing or mRNA cleavage, depending on the degree of complementarity between the miRNA and its target (13, 15).

In the past 10 years, functions of miRNAs have been investigated extensively in developmental and diseased conditions (16–18). Loss of function of Dicer in mice leads to early embryonic lethality at E7.5, suggesting miRNAs are essential during early embryonic development (14). To assess the global requirement of miRNA in cardiac development, Dicer was deleted in cardiac progenitor cells using the Nkx2.5-Cre line. These Dicer mutant embryos die at E12.5 due to pericardial edema and poor development of ventricular myocardium (19). In a separate study using a different Nkx2.5-Cre line, it was demonstrated that Dicer is important for programmed cell death during outflow tract morphogenesis (20). To understand the miRNA requirement in cardiac remodeling, Dicer was deleted in postnatal cardiomyocytes using tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase (αMHC-MerCreMer) (21). Dicer deletion in cardiomyocytes of 3-week-old mice resulted in sudden death within 1 week due to impaired cardiac function. Mutant hearts displayed mild ventricular remodeling, dramatic atrial enlargment, myocyte hypertrophy, myofiber disarray, ventricular fibrosis, and significant up-regulation of fetal gene transcripts (21).

In this study, we examined the function of Dicer in the developing epicardium using Gata5-Cre transgenic mice (2). Dicer mutants die immediately after birth and exhibit severe cardiac malformations. Epicardial EMT and the formation of coronary vascular smooth muscle is impaired. These results demonstrate a critical role for Dicer in epicardium during cardiac development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Dicer Mutant Mice

Epicardium-restricted Dicer mutant mice were generated by crossing the Gata5-Cre transgenic line with Dicerflox/flox mice (2, 22). Resulting Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/+ offspring were then back-crossed to Dicerflox/flox mice to obtain Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox mice. Embryos were obtained from timed pregnancies counting the afternoon of the plug date as E0.5. Embryos were dissected in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Genomic DNA prepared from yolk sacs or tail biopsies was used for PCR genotyping for both Gata5-Cre and floxed Dicer allele. All mice were kept on an sv129/C57BL6 mixed background. Primers used for genotyping were as follows: Gata5-Cre (G5CreF, 5′-ATTCTCCCACCGTCAGTACG-3′ and G5CreR, 5′-CGTTTTCTGAGCATACCTGGA-3′); Dicer flox (DicerF, 5′-CCTGACAGTGACGGTCCAAAG-3′ and DicerR, 5′-CATGACTCTTCAACTCAAACT-3′). Dicer deletion in the epicardium was confirmed by quantitative PCR for Dicer. In addition, to confirm that epicardial disruption of Dicer results in the loss of mature miRNAs, we performed quantitative PCR for miR-133a, miR-145, and miR-23b on RNA samples isolated from control and Dicer mutant epicardial explants (supplemental Fig. 1). All mouse work was performed according to the University of Pennsylvania animal care guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry

Hearts were dissected from control and Dicer mutant embryos and fixed in 4% PFA overnight. Samples were washed with PBS, dehydrated in methanol series, and stored in 100% methanol at −20 °C. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry for platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) was carried out as described previously (23). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 5% H2O2/methanol for 30 min at room temperature. The primary antibody (rat anti-mouse PECAM-1, clone MEC13.3, catalog no. 553370, BD Biosciences) was applied overnight at 4 °C at a dilution of 1:200. The secondary antibody was goat anti-rat IgG-HRP (catalog no. Ab 6120-250, Abcam) at a dilution of 1:500. Color development was performed using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine kit (SK-4100, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, VT). Stained hearts were cleared in 10% glycerol/PBS solution overnight before imaging and documentation. Immunohistochemical detection of SM22α was performed on paraffin sections of PFA-fixed hearts. Sections were treated with 0.1% trypsin for 10 min at 37 °C prior to antibody application. Primary SM22α antibody (goat polyclonal to SM22α, ab10135, Abcam) was applied overnight at 4 °C at a dilution of 1:100. The secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:500 to visualize the signals. Immunostaining on epicardial explants was done using a standard protocol. Briefly, epicardial cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min and then washed with PBS before incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Slides were then incubated overnight with the respective primary antibody (rabbit anti-ZO-1 (1:500), catalog no. 40-2200, Invitrogen; mouse anti-α smooth muscle actin (1:500), catalog no. A 2547, Sigma; mouse anti-vinculin (1:250), clone hVIN-1, catalog no. V9131, Sigma and Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin (1:500), catalog no. A12379, Invitrogen). Slides were washed with PBS for 30 min and then incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories).

Epicardial Cell Culture

Epicardial cell culture was performed as described previously (24). Briefly, hearts were dissected from E11.5 and E12.5 embryos and ventricles were placed epicardial side down on gelatin-coated chamber slides in epicardial culture medium (1:1 mixture of DMEM and medium 199 supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10% FBS, and 2 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2, PeproTech, NJ)). After 48 h, epicardial cells migrated onto the dish and formed an epithelial monolayer. Heart explants were then removed using sterile forceps. For SMC differentiation, epicardial cells were cultured in differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and with or without growth factors (TGF-β1 at 50 ng/ml, PeproTech, NJ)) for 6 more days before immunostaining. Medium was changed every 2 days. For the rescue of EMT defects seen in Dicer knock-outs, heart explants were cultured as described above. After 24 and 48 h, control, miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, or miR-429 mimic molecules (Thermo Scientific) were added at 2 μm to the culture with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Epicardial cells were cultured for 5 days before phalloidin immunostaining.

Collagen Gel Invasion Assay

Collagen gels were prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol (Millipore, Chemicon International catalog no. ECM675). Briefly, collagen gel solution was mixed with 5× M199 medium and neutralization solution in the recommended proportions. One hundred microliters of master mix was then pipetted into 96-well plates and allowed to polymerize for 60 min at 37 °C. E11.5 and E12.5 hearts were dissected, and the ventricle was used for explants. The hearts were allowed to grow on the gel for 3 days in the medium described above and then removed. Explants were cultured for another 2 days in the same medium. At the end of explant culture, cells were fixed in 2% PFA and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Explants were then stained with phalloidin antibody and DAPI. Images were taken using a Olympus MVX 100 microscope. To document epicardial cell invasion, images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope through z-stacks of 400-μm thickness. Three-dimensional reconstructions were done using Volocity software (Improvision, Coventry, England). Ten controls and eight Dicer knock-out heart explants were analyzed.

Proliferation Analysis

Epicardial cell proliferation was evaluated on control and Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox heart sections by Ki67 (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phosphohistone H3 (1:2000, Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), and MF20 (1:25, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) immunohistochemistry. DAPI (Vector Laboratories) was used to stain nuclei. NIH ImageJ software was used for quantification. For each genotype, images of six to eight different sections of three to four independent heart samples were used.

Histological Analysis

Histology was performed as described previously (23, 25, 26). Briefly, embryos from timed matings were dissected in PBS, fixed in 4% PFA overnight, washed with PBS, dehydrated in methanol, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned to 7 μm.

Quantitative Real-time PCR Analysis and MicroRNA Microarray

Quantitative PCR was performed as described (26, 27). Briefly, total RNA was isolated from epicardial explants using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and the SuperScript First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). Gene expression was measured by quantitative RT-PCR (ABI PRISM 7900) using SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Signals were normalized to corresponding GAPDH controls. PCR primer sequences are provided (supplemental Table 1). For microRNA microarray (Affymetrix) analysis, wild-type epicardial cells from E12.5 heart explants were used. After 48 h, hearts were removed, and the medium was replaced with epicardial culture medium (1:1 mixture of DMEM and medium 199 supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10% FBS) or epicardial culture medium plus 25 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2). Total RNA was harvested after 36 h with or without FGF2 using mirVanaTM miRNA isolation kit (Ambion, catalog no. AM1560). Experiments were performed in triplicate, and differences in gene expression levels were considered significant at p < 0.05 (supplemental Table 2).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the two-tailed Student's t test. Data were expressed as mean ± S.D. Differences were considered significant when the p value was <0.05.

RESULTS

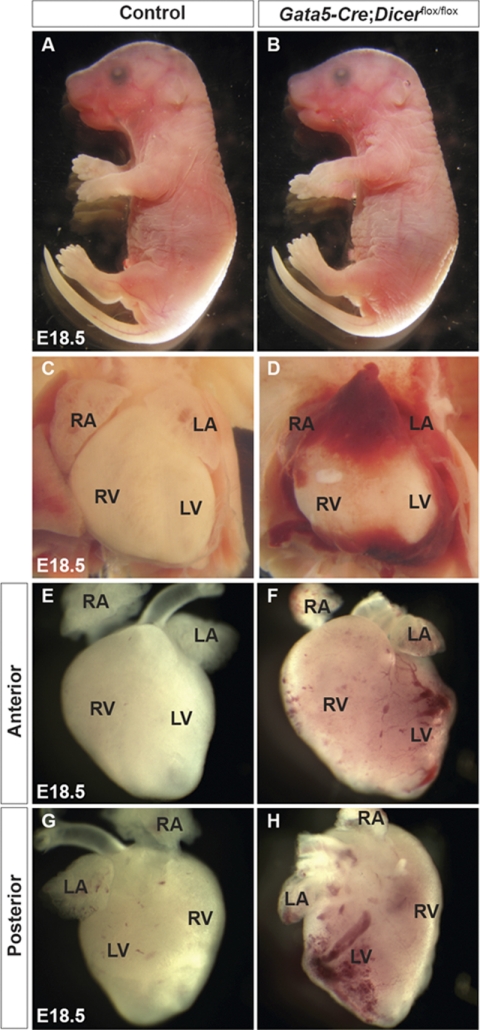

Epicardial Deletion of Dicer Leads to Perinatal Lethality

To determine a spatial and temporal requirement of Dicer during mouse epicardial and coronary vasculature development, we generated a conditional knock-out mouse. Dicer was deleted in the epicardium using Gata5-Cre transgenic mice, which express Cre recombinase in proepicardium by E9.5 and in epicardial cells by E10.5–E11.5 (2). Homozygous (Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/flox) mice were generated by crossing Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/+ males to Dicerflox/flox females. Genotyping of offspring from this mating did not identify any Dicer mutant mice (Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/flox) at postnatal day 1 or at later time points (Table 1). Thus, epicardial deletion of Dicer causes perinatal lethality. Mice with the genotypes Dicerflox/+, Dicerflox/flox, and Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/+ were present at all time points, did not show any morphological defects, and were used as controls. Despite their normal overall embryonic growth at E18.5 (Fig. 1, A and B), Dicer mutants displayed pronounced cardiac defects (Fig. 1, C–H). Mutant embryos showed hemorrhage within the pericardial space (Fig. 1, C and D). Subsequent removal of the pericardium revealed abnormal coronary vasculature with dilated and hemorrhagic vessels compared with littermate controls (Fig. 1, E–H).

TABLE 1.

Viability of Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox mice at different developmental stages from Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/+ × Dicerflox/flox crosses

| Age | Total no. | Genotypes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dicerflox/+ | Dicerflox/flox | Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/+ | Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox | ||

| >8 weeks | 171 | 60 | 56 | 55 | 0 |

| Postnatal day 1 | 64 | 22 | 19 | 23 | 0 |

| E18.5 | 86 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 25 |

| E14.5 | 92 | 21 | 25 | 23 | 23 |

| E12.5 | 68 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 16 |

FIGURE 1.

Cardiovascular defects in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox embryos. Dicer mutant mice were born alive but died within 1 day due to cardiovascular defects. Compared with control embryos, Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox embryos appeared grossly normal (A and B). Compared with control (C), Dicer mutant embryos showed pericardial hemorrhage (D). After removal of the pericardium, control hearts showed mature vasculature (E and G), whereas all mutant embryos had evident abnormal blood vessels and hemorrhages on the ventricular wall (F and H). RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

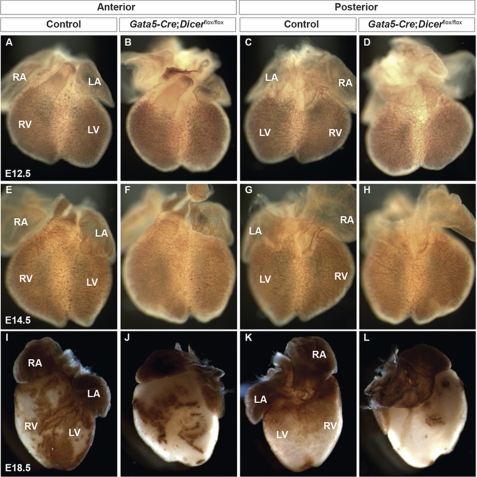

Impaired Coronary Vasculature Development in Dicer Mutants

To determine whether loss of Dicer in epicardium has any effect on coronary vasculature patterning and maturation, whole-mount PECAM-1 immunostaining was performed on control and Dicer mutant hearts at embryonic stages E12.5, E14.5, and E18.5 (Fig. 2). At E12.5, endothelial cells form a primitive but elaborate vascular network covering the heart. Whole-mount PECAM-1 immunostaining revealed that early vascular patterning in Dicer mutant hearts at E12.5 and E14.5 is preserved compared with controls (Fig. 2, A–H). In contrast, PECAM-1 staining at E18.5 showed severe coronary vessel defects in Dicer mutant hearts compared with controls (Fig. 2, I–L). Mutant hearts showed a relative paucity of mature vasculature, especially over the posterior surface of the heart (Fig. 2, J and L). These results indicated that Dicer was not required for early patterning of the endothelial vascular plexus but was required during the maturation and remodeling process of the coronary vasculature.

FIGURE 2.

Vascular patterning and remodeling of the coronaries in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox embryos. Whole-mount PECAM-1 staining of E12.5, E14.5, and E18.5 wild-type and Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox embryos. Whole-mount PECAM-1 staining of E12.5 and E14.5 showed no obvious vascular patterning defects in Dicer mutant hearts compared with controls (A–H). Similar staining of staged match littermates at E18.5 reveals loss of normal vascular development. In control hearts, more mature coronary vessels are formed compared with Dicer mutant hearts (I–L). The coronary vessel maturation on the posterior surface of the heart is seems to be more severely affected than the anterior surface in mutants (J and L). RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

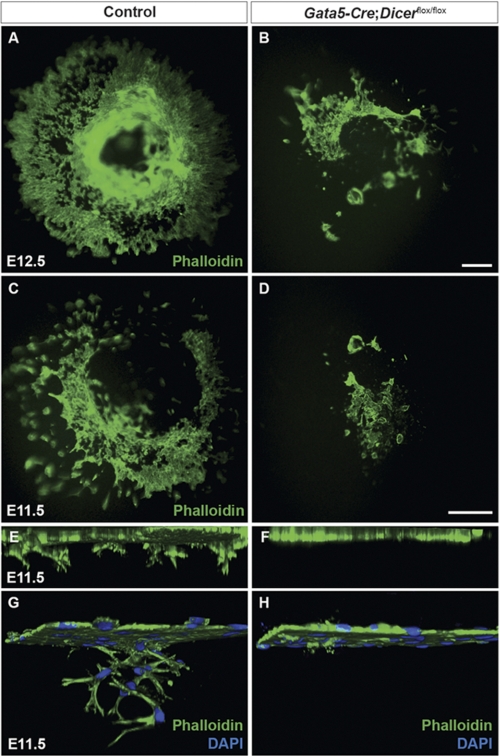

Dicer Is Required for Epicardial EMT

EMT is essential for the development of many tissues and organs, including the epicardium (28). To examine whether coronary vasculature defects seen in Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/flox hearts were associated with defects in epicardial EMT, a collagen gel invasion assay was performed using epicardial explants from control and Dicer mutants at E11.5 and E12.5. Explants were cultured in EMT-induced medium containing FBS and FGF2 as described previously (24). Epicardium-derived cells lose their epithelial nature, reduce cell-cell contacts, and migrate and invade the collagen gel over time. After 5 days of culture, epicardium-derived cells were visualized by phalloidin immunofluorescence. In control samples, epicardial cells migrated over the surface and invaded the collagen gel (Fig. 3, A, C, E, and G). However, migration and invasion of collagen gel by Dicer mutant epicardial cells were severely perturbed (Fig. 3, B, D, F, and H). We performed miRNA microarrays to identify miRNAs regulating epicardial EMT. We compared miRNA expression between explants treated with or without FGF2, which stimulates EMT. Among the significantly altered miRNAs, we identified several members of the miR-200 family (supplemental Table 2). As prior studies have implicated the miR-200 family in EMT processes in other tissues (29), and because the miR-200 family is Dicer-dependent (30), we sought to determine whether miR-200 family mimics could rescue defective EMT observed in Dicer mutant explants. However, ectopic expression of miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, or miR429 mimics failed to rescue EMT in Dicer mutant epicardial explants (supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that none of these is sufficient to fully explain the defects observed in Dicer mutants.

FIGURE 3.

Epicardial epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is decreased in Dicer mutant hearts. Dissected hearts from E11.5 and E12.5 embryos were explanted on a three-dimensional collagen gel matrix and then stained with Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin and DAPI to visualize epicardial cell migration and invasion into the collagen matrix. In control explants, epicardial cells migrated on the surface of the gel in an organized manner. However, in Dicer mutant explants, epicardial cell migration was severely affected (A–D). Confocal images were taken from E11.5 heart explants to analyze epicardial cell invasion (E–H). Three-dimensional reconstructions were generated from confocal images to analyze cell invasion along z-axes (E–H). In control explants, z-stacks showed nice invasion of epicardial cells into the collagen matrix. However, Dicer mutant epicardial cells showed significant reduction in invasion depth compared with controls (E and F). Higher magnification of E and F is shown in G and H, respectively. Ten controls and eight Dicer mutant heart explants were analyzed. Scale bars, 50 μm.

An important early step in epicardial EMT is the loss of cell-cell adhesion, and several adhesion molecules have been shown to be regulated spatiotemporally during this process (31, 32). To further examine whether Dicer is required in cell-cell adhesion, expression and distribution of the tight junction protein ZO-1 (zona occludens-1, encoded by the Tjp1 gene) was analyzed on cultured epicardial cells. Translocation of ZO-1 between the cell surface and cytoplasm has been implicated in EMT (33). In control epicardial explants, ZO-1 expression was weak and diffuse, and its distribution was not restricted to the cell surface, a hallmark of cells undergoing EMT (Fig. 4A). However, in epicardial cells derived from Dicer mutant hearts, ZO-1 remained localized to the cell surface, and cells were tightly attached to each other suggesting an early defect of EMT in Dicer mutants (Fig. 4B). Consistent with this interpretation, quantitative RT-PCR gene expression analysis revealed a significant reduction in Wt1, Snail1, Snail2, and Twist1 in mutant explants compared with controls, and E-cadherin expression was increased significantly (Fig. 4C). These gene expression changes are consistent with deficient EMT (34).

FIGURE 4.

Altered cell adhesion in Dicer mutant epicardial explants. Cellular distribution of ZO-1, a tight junction protein, was analyzed in control and Dicer mutant epicardial explants from E11.5 embryos by immunostaining (green). Explants were cultured in an EMT-inducing medium (FBS (10%) + FGF2 (2 ng/ml)). ZO-1 expression pattern in control explants is diffused and not restricted to the surface of cells, suggesting that these cells are undergoing EMT (A). In contrast, Dicer mutant explants showed a continuous staining on the cell surface, indicating their epithelial nature (B). FGF2-induced EMT is reduced significantly in Dicer mutant explants. Quantitative RT-PCR of candidate EMT regulators in control and Dicer mutant epicardial explants are shown (C). Expression levels of Tbx18, N-cadherin, and α-4 integrin were not changed. Expression levels of Wt1, Snail1, Snail2, and Twist1 were down-regulated significantly in mutant explants. E-cadherin transcript levels were significantly up-regulated. Significant differences were defined by *, p < 0.05 (n = 6). Magnification in A and B is ×40.

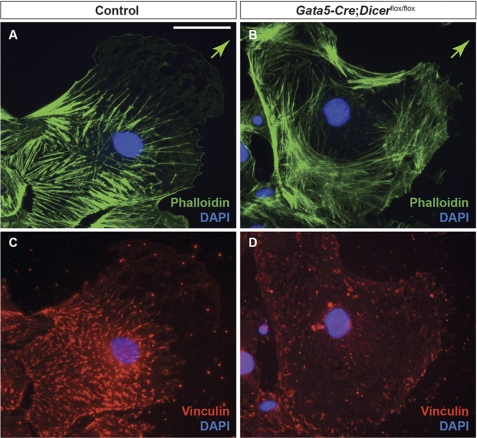

Cytoskeletal and Cellular Defects in Dicer Mutants

EMT involves cytoskeletal reorganization (35). To determine whether loss of Dicer had any effect on actin cytoskeleton arrangement and focal adhesions, epicardial explants from E11.5 control and Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/flox hearts were cultured, and the distribution of actin fibers and focal adhesion sites was visualized by immunofluorescence for phalloidin and vinculin, respectively. In control explants, actin filaments were aligned in the direction of migration. In contrast, actin filaments were more randomly distributed in mutant explants (Fig. 5, A and B). Next, we analyzed the organization of adhesion plaques, which serve as attachment sites for stress fibers in control and mutant cells (36). Dicer mutant cells showed significant reduction in the number and size of focal adhesion plaques as detected by vinculin staining, suggesting that the adhesion dynamics (assembly and disassembly of focal adhesion) was affected in mutant epicardial cells compared with control (Fig. 5, C and D).

FIGURE 5.

Cytoskeletal organization is altered in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox hearts. Cellular distribution and arrangement of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion plaques were analyzed in control and Dicer mutant epicardial explants from E11.5 embryos by immunostaining. Cultured epicardial cells were stained with phalloidin (A and B, green) and vinculin antibody (C and D, red). Actin stress fibers in control cells are aligned with the direction of cell migration (indicated by arrow in A and B) (A). In contrast, knock-out cells showed random organization of actin fibers that were not often aligned with the direction of cell migration (B). Vinculin staining on these same cells showed nicely formed adhesion plaques in controls but not in Dicer mutant cells (C and D). Scale bars, 10 μm.

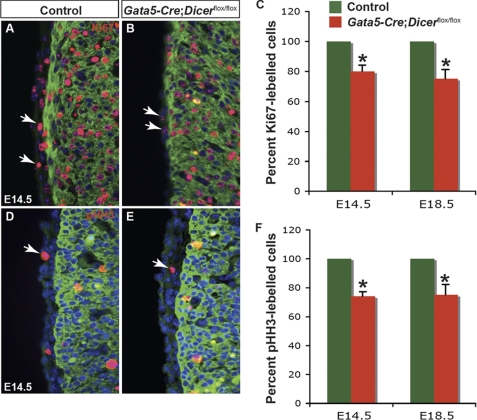

Proepicardial cells proliferate and migrate over the surface of the heart to form the primitive epicardium. To determine whether loss of Dicer had any effect on epicardial cell proliferation, immunohistochemistry for Ki67 and phosphohistone H3 was performed at E14.5 and E18.5. Gata5-Cre:Dicerflox/flox epicardium showed significant reduction in Ki67 staining (∼79% at E14.5 and ∼75% at E18.5) when compared with controls (Fig. 6, A–C). Similar results were observed when proliferation was analyzed by phosphohistone H3 staining (Fig. 6, D–F). As a control, proliferation analysis in Dicer mutant lung did not show any significant difference compared with control lungs (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Epicardial cell proliferation is decreased in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox hearts. Immunostaining for Ki67 or phosphohistone H3 (red), MF-20 (green), and DAPI (blue) were performed on heart sections from E14.5 and E18.5 control and Dicer mutant embryos. Epicardial cells in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox hearts demonstrated a significant reduction in staining with Ki67 compared with control hearts (A, B, and summarized in C). Similar decreases in proliferation in Dicer mutants were observed by immunohistochemistry analysis with phosphohistone H3 (D–F). Quantification of phosphohistone H3 (pHH3) and Ki67-positive cells was performed on six sections each from four individual hearts (from E14.5 and E18.5) and averaged. *, p < 0.05. Arrows represent Ki67 or phosphohistone-H3 positive epicardial cells.

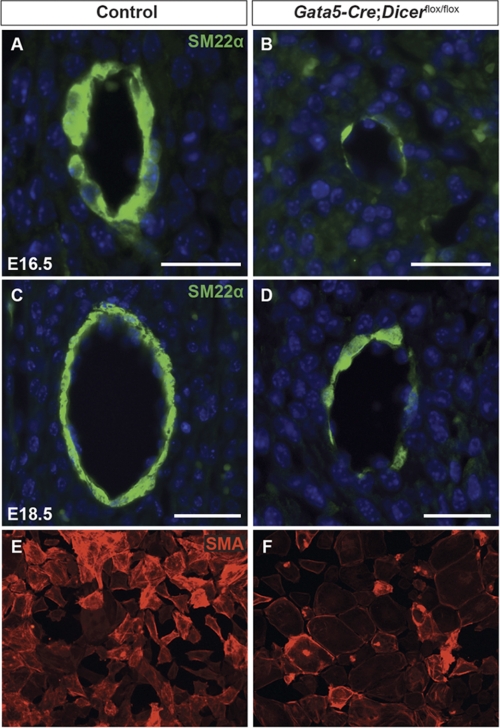

Differentiation of Epicardium-derived Cells into Coronary Smooth Muscle Is Impaired in Dicer Mutants

Epicardium-derived SMCs are essential components of coronary vessels undergoing maturation and remodeling (37), and defective smooth muscle differentiation could contribute to coronary vascular defects. PECAM-1 staining confirmed that initial coronary endothelial patterning is intact in Dicer mutant hearts (Fig. 2, A–H). Later stages of vascular remodeling and smooth muscle differentiation were analyzed at E16.5 and E18.5 (Fig. 7). At both time points, the SMC marker SM22α was expressed robustly in the vasculature of control coronary vessels, indicating SMC differentiation (Fig. 7, A and C). In contrast, very weak expression of SM22α was detected in the coronary vasculature of Dicer mutant hearts (Fig. 7, B and D). This observation suggests that Dicer mutant EPDCs failed to differentiate into SMCs in the developing coronary vasculature. To further examine this possibility, we utilized a well established in vitro culture assay for EPDC-derived smooth muscle differentiation (38). After 6 days of culture in medium containing TGF-β1, smooth muscle differentiation was assessed by immunofluorescence for SMA. Consistent with in vivo data, Dicer mutant epicardial explants showed impairment of SMA expression when compared with controls (Fig. 7, E and F).

FIGURE 7.

Smooth muscle differentiation is decreased in Gata5-Cre;Dicerflox/flox hearts. Paraffin sections from E16.5 and E18.5 hearts were stained with SM22α antibody in control (A and C) and Dicer mutant embryos (B and D) to analyze smooth muscle differentiation during coronary vasculature development. Dicer mutant hearts showed a significant reduction in the number of smooth muscle cells around coronaries compared with controls (B and D). Smooth muscle differentiation was also assessed in vitro (E and F). Epicardial explants from control and Dicer mutants were treated with TGF-β1 (50 ng/ml) to induce SMC differentiation. Mouse anti-α smooth muscle actin (SMA) antibody staining was done to visualize differentiated smooth muscle cells. Magnification in E and F is ×40. Scale bars, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

miRNAs are 19–25-nucleotide single-stranded non-coding RNAs that are transcribed but not translated into proteins. miRNAs are important regulators of gene expression in development, differentiation, and homeostasis. The ribonuclease III enzyme Dicer is essential for the processing of miRNAs that act to repress transcription and/or translation of target genes (18, 39). Dicer functions have been investigated in different tissues, including the heart (20, 40–43). Loss of Dicer in adult heart leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure (21). In this study, we have presented evidence to show that Dicer is important in the epicardium for coronary vasculature development. Using Gata5-Cre to delete Dicer in the proepicardium and epicardial tissue, our data indicate that Dicer and, by implication miRNAs, play essential functions during epicardial development.

The coronary vasculature forms from an initial vascular endothelial plexus that remodels in association with supporting cells, including vascular smooth muscle, that derive from epicardium. In Dicer mutants, the coronary vascular endothelial plexus appears to form normally. Epicardial EMT, proliferation, and smooth muscle differentiation are impaired in the absence of Dicer, and the result is a marked deficiency of coronary vascular smooth muscle. We hypothesize that this defect, in turn, results in a failure of vascular remodeling and vessel integrity, pericardial hemorrhage, myocardial dysfunction, and perinatal lethality. A tissue-specific function for Dicer in epicardial derivatives was not apparent previously because global deletion of Dicer in mice results in embryonic death at ∼E7.5 (14). A hypomorphic allele of Dicer has also been described, in which exons 1 and 2 were deleted, which resulted in mid gestation embryonic lethality and yolk sac vascular defects (44).

miRNAs have been implicated previously in regulation of EMT during development and disease (28, 31). For example, miR-103/107 promote EMT by inhibiting Dicer expression, causing global miRNA down-regulation in breast cancer (45). miR-155 plays important roles in TGFβ-induced EMT, cell migration, and invasion in breast cancer (46). Recent reports have demonstrated the importance of miR-200 family (miR-200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429) regulation of EMT (47), and our results indicate that this family of microRNAs is down-regulated during FGF2-induced epicardial EMT. However, we were not able to rescue EMT in explant assays of Dicer mutants with miR-200 mimics, suggesting that other microRNAs also may be involved. Our results that demonstrate a critical role for Dicer in epicardial EMT provide further support for the powerful role of miRNAs in this process. In particular, we noted defective relaxation of cell-cell adhesion in Dicer mutants, suggesting an early defect. Gene expression, cytoskeletal reorganization, and migration were all affected.

The development of the epicardium is a dynamic process that requires extensive proliferation and migration of proepicardial precursors during early cardiac development. Recently, it was demonstrated that epicardial cells undergoing cell cycle arrest fail to invade underlying myocardium (48). Consistent with Dicer function in other systems, we found a significant decrease in the proliferation rate of Dicer mutant epicardial cells compared with controls. Perhaps defective proliferation contributes to the defects in migration and myocardial invasion seen in Dicer mutant hearts.

Smooth muscle cells of the heart are derived from a variety of embryonic progenitors. During early cardiac development, Nkx2.1+, Isl1+ cardiac progenitors and Mesp1+, Flk1+ hemangioblast progenitors have potential to differentiate into SMCs (49, 50). Fate-mapping analyses in mouse have demonstrated that multipotent neural crest cells can also differentiate into SMC and contribute to the embryonic heart (51, 52). In addition, proepicardium and epicardium-derived progenitor cells undergo EMT, differentiate into SMCs, and contribute largely to the maturation and remodeling of coronary vasculature. Our data in vivo and in vitro demonstrate that smooth muscle differentiation of EPDCs, and contribution to the maturation and remodeling of coronary vasculature was severely compromised in Dicer mutant hearts. Recently, Dicer was deleted using SM22-Cre to investigate Dicer functions more broadly during vascular smooth muscle development. The loss of Dicer in vascular smooth muscle resulted in hemorrhage and embryonic lethality (53, 54), although specific defects in coronary vasculature were not noted. Inducible deletion of Dicer in adult vascular smooth muscle has also shown a vital role for miRNAs in vascular homeostasis and blood pressure control (55). Several reports have implicated miR-143/145 in vascular smooth muscle behavior (56–58), although the defects in the adult inducible Dicer mutants were more severe than those reported in miR-143/145 mutants. Our data indicates that coronary vascular smooth muscle derived from epicardium is also dependent upon Dicer function.

In addition to its role during cardiac development, epicardium may also play an important role in cardiac scarring, homeostasis, and regeneration after injury. In both zebrafish and mice, the epicardium is activated broadly in response to injury and may secrete paracrine factors and/or undergo EMT to contribute new cells to the area of damage (9, 59, 60). In addition to further analysis of coronary development, it will be of interest to examine the roles of Dicer and miRNAs during the epicardial response to injury in the adult.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Epstein lab members for helpful discussion. We thank Ashley Cohen for assistance with animal husbandry, Jun Li for technical help, and Jasmine Zhao (University of Pennsylvania CDB/CVI Microscopy Core) for assistance with microscopy. We also thank Kurt Engleka for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant U01 HL100405. This work was also supported by the Grant from Spain for cardiovascular regenerative biology (to J. A. E.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. 1 and 2.

- E10.5

- embryonic day 10.5

- EMT

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- PFA

- paraformaldehyde

- EPDC

- epicardium-derived cell

- miRNA

- microRNA

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell.

REFERENCES

- 1. Männer J., Pérez-Pomares J. M., Macías D., Muñoz-Chápuli R. (2001) Cells Tissues Organs 169, 89–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merki E., Zamora M., Raya A., Kawakami Y., Wang J., Zhang X., Burch J., Kubalak S. W., Kaliman P., Belmonte J. C., Chien K. R., Ruiz-Lozano P. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18455–18460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai C. L., Martin J. C., Sun Y., Cui L., Wang L., Ouyang K., Yang L., Bu L., Liang X., Zhang X., Stallcup W. B., Denton C. P., McCulloch A., Chen J., Evans S. M. (2008) Nature 454, 104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou B., Ma Q., Rajagopal S., Wu S. M., Domian I., Rivera-Feliciano J., Jiang D., von Gise A., Ikeda S., Chien K. R., Pu W. T. (2008) Nature 454, 109–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mikawa T., Gourdie R. G. (1996) Dev. Biol. 174, 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Männer J. (1993) Anat. Embryol. 187, 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Männer J., Schlueter J., Brand T. (2005) Dev. Dyn. 233, 1454–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Winter E. M., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C. (2007) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64, 692–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Major R. J., Poss K. D. (2007) Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models 4, 219–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Porrello E. R., Mahmoud A. I., Simpson E., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N., Sadek H. A. (2011) Science 331, 1078–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smart N., Risebro C. A., Melville A. A., Moses K., Schwartz R. J., Chien K. R., Riley P. R. (2007) Nature 445, 177–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He L., Hannon G. J. (2004) Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim V. N. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernstein E., Kim S. Y., Carmell M. A., Murchison E. P., Alcorn H., Li M. Z., Mills A. A., Elledge S. J., Anderson K. V., Hannon G. J. (2003) Nat. Genet. 35, 215–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carmell M. A., Hannon G. J. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 214–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alvarez-Garcia I., Miska E. A. (2005) Development 132, 4653–4662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harfe B. D. (2005) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Y., Srivastava D. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao Y., Ransom J. F., Li A., Vedantham V., von Drehle M., Muth A. N., Tsuchihashi T., McManus M. T., Schwartz R. J., Srivastava D. (2007) Cell 129, 303–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Saxena A., Tabin C. J. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 87–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. da Costa Martins P. A., Bourajjaj M., Gladka M., Kortland M., van Oort R. J., Pinto Y. M., Molkentin J. D., De Windt L. J. (2008) Circulation 118, 1567–1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harfe B. D., McManus M. T., Mansfield J. H., Hornstein E., Tabin C. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10898–10903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh M. K., Christoffels V. M., Dias J. M., Trowe M. O., Petry M., Schuster-Gossler K., Bürger A., Ericson J., Kispert A. (2005) Development 132, 2697–2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zamora M., Männer J., Ruiz-Lozano P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18109–18114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh M. K., Petry M., Haenig B., Lescher B., Leitges M., Kispert A. (2005) Mech. Dev. 122, 131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Singh M. K., Li Y., Li S., Cobb R. M., Zhou D., Lu M. M., Epstein J. A., Morrisey E. E., Gruber P. J. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 1765–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh M. K., Elefteriou F., Karsenty G. (2008) Endocrinology 149, 3933–3941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thiery J. P. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 740–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gregory P. A., Bert A. G., Paterson E. L., Barry S. C., Tsykin A., Farshid G., Vadas M. A., Khew-Goodall Y., Goodall G. J. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Choi P. S., Zakhary L., Choi W. Y., Caron S., Alvarez-Saavedra E., Miska E. A., McManus M., Harfe B., Giraldez A. J., Horvitz H. R., Schier A. F., Dulac C. (2008) Neuron 57, 41–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thiery J. P., Sleeman J. P. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thiery J. P. (2003) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Polette M., Mestdagt M., Bindels S., Nawrocki-Raby B., Hunziker W., Foidart J. M., Birembaut P., Gilles C. (2007) Cells Tissues Organs 185, 61–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martínez-Estrada O. M., Lettice L. A., Essafi A., Guadix J. A., Slight J., Velecela V., Hall E., Reichmann J., Devenney P. S., Hohenstein P., Hosen N., Hill R. E., Muñoz-Chapuli R., Hastie N. D. (2010) Nat. Genet. 42, 89–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yilmaz M., Christofori G. (2009) Cancer Metastasis Rev. 28, 15–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Petit V., Thiery J. P. (2000) Biol. Cell 92, 477–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Risau W. (1997) Nature 386, 671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Tuyn J., Atsma D. E., Winter E. M., van der Velde-van Dijke I., Pijnappels D. A., Bax N. A., Knaän-Shanzer S., Gittenberger-de Groot A. C., Poelmann R. E., van der Laarse A., van der Wall E. E., Schalij M. J., de Vries A. A. (2007) Stem Cells 25, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nilsen T. W. (2007) Trends Genet. 23, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zehir A., Hua L. L., Maska E. L., Morikawa Y., Cserjesi P. (2010) Dev. Biol. 340, 459–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou L., Seo K. H., He H. Z., Pacholczyk R., Meng D. M., Li C. G., Xu J., She J. X., Dong Z., Mi Q. S. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10266–10271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang Z. P., Chen J. F., Regan J. N., Maguire C. T., Tang R. H., Dong X. R., Majesky M. W., Wang D. Z. (2010) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 2575–2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen J. F., Murchison E. P., Tang R., Callis T. E., Tatsuguchi M., Deng Z., Rojas M., Hammond S. M., Schneider M. D., Selzman C. H., Meissner G., Patterson C., Hannon G. J., Wang D. Z. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2111–2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang W. J., Yang D. D., Na S., Sandusky G. E., Zhang Q., Zhao G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9330–9335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martello G., Rosato A., Ferrari F., Manfrin A., Cordenonsi M., Dupont S., Enzo E., Guzzardo V., Rondina M., Spruce T., Parenti A. R., Daidone M. G., Bicciato S., Piccolo S. (2010) Cell 141, 1195–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kong W., Yang H., He L., Zhao J. J., Coppola D., Dalton W. S., Cheng J. Q. (2008) Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 6773–6784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mongroo P. S., Rustgi A. K. (2010) Cancer Biol. Ther. 10, 219–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu M., Smith C. L., Hall J. A., Lee I., Luby-Phelps K., Tallquist M. D. (2010) Dev. Cell 19, 114–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Domian I. J., Chiravuri M., van der Meer P., Feinberg A. W., Shi X., Shao Y., Wu S. M., Parker K. K., Chien K. R. (2009) Science 326, 426–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kattman S. J., Huber T. L., Keller G. M. (2006) Dev. Cell 11, 723–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. High F. A., Zhang M., Proweller A., Tu L., Parmacek M. S., Pear W. S., Epstein J. A. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 353–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Stoller J. Z., Epstein J. A. (2005) Semin Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 704–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Albinsson S., Suarez Y., Skoura A., Offermanns S., Miano J. M., Sessa W. C. (2010) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 1118–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pan Y., Balazs L., Tigyi G., Yue J. (2011) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 408, 369–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Albinsson S., Skoura A., Yu J., DiLorenzo A., Fernández-Hernando C., Offermanns S., Miano J. M., Sessa W. C. (2011) PLoS One 6, e18869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cheng Y., Liu X., Yang J., Lin Y., Xu D. Z., Lu Q., Deitch E. A., Huo Y., Delphin E. S., Zhang C. (2009) Circ. Res. 105, 158–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elia L., Quintavalle M., Zhang J., Contu R., Cossu L., Latronico M. V., Peterson K. L., Indolfi C., Catalucci D., Chen J., Courtneidge S. A., Condorelli G. (2009) Cell Death Differ. 16, 1590–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Xin M., Small E. M., Sutherland L. B., Qi X., McAnally J., Plato C. F., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 2166–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Poss K. D. (2007) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 36–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhou B., Honor L. B., He H., Ma Q., Oh J. H., Butterfield C., Lin R. Z., Melero-Martin J. M., Dolmatova E., Duffy H. S., Gise A. V., Zhou P., Hu Y. W., Wang G., Zhang B., Wang L., Hall J. L., Moses M. A., McGowan F. X., Pu W. T. (2011) J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1894–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.