Background: Oxygen activation by aryl-alcohol oxidase, a key step in lignin biodegradation, is investigated.

Results: Mutation of Phe-501, forming a bottleneck in the access channel, strongly affects the oxygen kinetic constants.

Conclusion: An aromatic side chain at this position helps oxygen to attain a catalytically relevant position near flavin C4a and catalytic residue His-502.

Significance: The possibility to modulate the oxygen reactivity of related GMC oxidoreductases is demonstrated.

Keywords: Computational Biology, Crystal Structure, Docking, Enzyme Kinetics, Enzyme Mechanisms, Flavoproteins, Lignin Degradation, Oxygen Diffusion, Site-directed Mutagenesis, GMC Oxidoreductases

Abstract

Aryl-alcohol oxidase (AAO) is a flavoenzyme responsible for activation of O2 to H2O2 in fungal degradation of lignin. The AAO crystal structure shows a buried active site connected to the solvent by a hydrophobic funnel-shaped channel, with Phe-501 and two other aromatic residues forming a narrow bottleneck that prevents the direct access of alcohol substrates. However, ligand diffusion simulations show O2 access to the active site following this channel. Site-directed mutagenesis of Phe-501 yielded a F501A variant with strongly reduced O2 reactivity. However, a variant with increased reactivity, as shown by kinetic constants and steady-state oxidation degree, was obtained by substitution of Phe-501 with tryptophan. The high oxygen catalytic efficiency of F501W, ∼2-fold that of native AAO and ∼120-fold that of F501A, seems related to a higher O2 availability because the turnover number was slightly decreased with respect to the native enzyme. Free diffusion simulations of O2 inside the active-site cavity of AAO (and several in silico Phe-501 variants) yielded >60% O2 population at 3–4 Å from flavin C4a in F501W compared with 44% in AAO and only 14% in F501A. Paradoxically, the O2 reactivity of AAO decreased when the access channel was enlarged and increased when it was constricted by introducing a tryptophan residue. This is because the side chain of Phe-501, contiguous to the catalytic histidine (His-502 in AAO), helps to position O2 at an adequate distance from flavin C4a (and His-502 Nϵ). Phe-501 substitution with a bulkier tryptophan residue resulted in an increase in the O2 reactivity of this flavoenzyme.

Introduction

Biodegradation of wood and other lignified plant materials is a key step for recycling the carbon fixed by photosynthesis and also represents a central issue for the industrial use of renewable biomass for the sustainable production of fuels, materials, and chemicals (1). Two groups of basidiomycetes, the so-called white and brown rot fungi, are the only living organisms that are able to efficiently degrade the highly recalcitrant lignified materials (2).

Activation of molecular oxygen to hydrogen peroxide by extracellular oxidases represents a common step in both fungal decay strategies, as shown by biochemical (2, 3) and genomic (4, 5) evidence. Brown rot basidiomycetes reduce peroxide by ferrous iron, yielding hydroxyl radical that depolymerizes cellulose, leaving a lignin-rich residue. In contrast, the white rot decay is based on peroxide activation of high redox potential fungal heme peroxidases that depolymerize lignin, leaving a cellulose-rich residue (6). The mechanism of enzymatic attack on lignin by the latter group of fungi has been extensively investigated because of its biotechnological interest (7, 8).

Aryl-alcohol oxidase (AAO4; EC 1.1.3.7) is a flavo-oxidase from the GMC (glucose-methanol-choline oxidase) superfamily responsible for oxygen activation by wood-rotting fungi together with methanol oxidase and pyranose-2 oxidase (two other GMC oxidoreductases) and glyoxal oxidase (a copper radical oxidase) among other enzymes (9, 10). AAO has been reported in fungi from the genera Pleurotus (11, 12) and Bjerkandera (13), and the enzyme from Pleurotus eryngii, a species degrading lignin selectively (14), has been the most thoroughly investigated (15–17). The above fungi also secrete 4-methoxylated (18) and 3-chlorinated 4-methoxylated (18, 19) benzylic metabolites that are “redox-cycled” by AAO and mycelium (aldehyde and acid) dehydrogenases (20). This results in a continuous supply of extracellular H2O2 to peroxidases, such as the lignin-degrading versatile peroxidase produced by these fungi (9, 21).

The first structural-functional studies of P. eryngii AAO were performed after homology modeling of the enzyme (22). More recently, the crystal structure of AAO has been reported, showing two unique structural motifs in GMC proteins that limit the access of substrates to the active site (23). The mechanism of AAO oxidation of aromatic and aliphatic polyunsaturated alcohols (with conjugated primary hydroxyls) has been investigated using steady- and transient-state kinetics in combination with substrate and solvent isotope effects (24), and its ability to oxidize aromatic aldehydes (after hydration to the gem-diol forms) has been demonstrated recently (25). The mechanism is similar to that proposed for other GMC oxidoreductases (26) where alcohol oxidation takes place by hydride transfer to oxidized flavin aided by a catalytic base (P. eryngii AAO His-502), but the timing of H− and H+ transfers in AAO is different, and no alkoxide intermediate is formed (27). The mechanism of O2 reduction at the active site of GMC oxidoreductases is still not fully understood (28–31). O2 access to the flavoenzyme active site has also been considered in recent studies (32–35). However, only preliminary investigations on the AAO reaction with O2 have been performed to date (36), although the physiological (environmental) role of this oxidase is oxygen activation in lignocellulose decay.

In this study, we first used the crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 3FIM) to investigate O2 access to the buried active site of AAO using the Protein Energy Landscape Exploration (PELE) algorithm for ligand diffusion simulation (37). In a second step, site-directed mutagenesis (followed by bisubstrate steady-state kinetics, transient-state kinetics, and turnover studies of the variants obtained) in combination with computational calculations (free O2 diffusion by PELE inside the active-site cavity of AAO and three in silico variants) was used to demonstrate the key role of Phe-501 in aiding O2 to attain a catalytically relevant position near flavin C4a, involved in flavoprotein reduction of O2 (30), and the Nϵ of contiguous His-502, involved in both the oxidative and reductive AAO half-reactions (27, 36) (see AAO catalytic cycle in supplemental Fig. S1).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Enzyme and Mutants

Native (wild-type) recombinant AAO was obtained by Escherichia coli expression of the mature P. eryngii AAO cDNA (GenBankTM accession number AF064069) followed by in vitro activation (38). AAO variants were prepared using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For PCRs, the AAO cDNA cloned into the pFLAG1 vector was used as a template, and the following oligonucleotides (direct sequences) bearing mutations (underlined) at the corresponding triplets (boldface) were used as primers: F501A, 5′-CAACGCCAACACGATTGCCCACCCAGTTGGAACG-3′; F501Y, 5′-CAACGCCAACACGATTTACCACCCAGTTGGAACG-3′; and F501W, 5′-CAACGCCAACACGATTTGGCACCCAGTTGGAACG-3′. Mutations were confirmed by sequencing (GS-FLX sequencer from Roche Applied Science), and the mutants were produced (38). Enzyme concentrations were determined using the molar absorbances of AAO and its F501A, F501Y, and F501W variants (ϵ463 = 11,050, 10,389, 10,729, and 9944 m−1 cm−1, respectively) estimated by heat denaturation as described below. Enzyme (10–15 μm) was dissolved in 0.01 m phosphate (pH 6.0), and the absorbance at 463 nm was recorded. The sample was incubated at 100 °C for 5 min and centrifuged to remove the unfolded protein. The supernatant was recovered, and the free FAD concentration was estimated using an ϵ450 of 11,300 m−1 cm−1 (39).

Steady-state Kinetics

Enzyme activity was estimated by oxidation of p-methoxybenzyl alcohol (from Sigma-Aldrich) to p-methoxybenzaldehyde (p-anisaldehyde; ϵ285 = 16,950 m−1 cm−1) (16). Maximal steady-state kinetic constants for native AAO and its variants in bisubstrate kinetics were determined in 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) at 12 °C by varying simultaneously the concentrations of alcohol (in the 10–2000 μm range) and O2 (61, 152, 319, 668, and 1520 μm final concentrations obtained by bubbling buffer with different O2/N2 gas mixtures for 15 min). The two-substrate dependence steady-state kinetic observed rates were fit using SigmaPlot (Systat Software, Richmond, CA) to Equations 1 and 2, which describe a ternary complex mechanism and a ping-pong mechanism, respectively.

|

|

In these equations, e represents the enzyme concentration; kcat is the maximal turnover (under both O2 and reducing substrate saturation); S is the concentration of the alcohol substrate; B is the concentration of O2; Km(Al) and Km(Ox) are the Michaelis constants for S and B, respectively; and Kd is the dissociation constant for the enzyme-substrate complex.

Stopped-flow Measurements

An Applied Photophysics SX18.MV stopped-flow spectrophotometer interfaced with an Acorn computer was used to further characterize native AAO and its variants. SX18.MV software and Xscan software were used for experiments with single-wavelength and diode array (350–700 nm) detectors, respectively.

Reductive half-reactions were studied under anaerobic conditions (40). Tonometers containing enzyme or substrate solutions were made anaerobic by successive evacuation and flushing with argon. These solutions also contained glucose (10 mm) and glucose oxidase (10 units/ml) to ensure anaerobiosis. Drive syringes in the apparatus were made anaerobic by sequentially passing dithionite and O2-free buffer. Measurements were carried out in 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) at 12 °C. (AAO reduction was too fast at 25 °C.) Spectral evolution was studied by global analysis and numerical integration methods using Pro-K software (Applied Photophysics Ltd.). Data could be fitted to a single-step A→B model. Accurate observed rate constants (kobs) were obtained from single-wavelength traces at 462 nm and fit into a standard single-exponential decay. kobs values at different substrate concentrations (S) were fitted to Equation 3,

|

where kred and Kd are the flavin reduction and dissociation constants, respectively.

Oxidative half-reactions were studied using the same stopped-flow equipment. The rate constants were measured from the increase of 462 nm absorbance that results from mixing reduced enzyme in anaerobic 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) with the same buffer equilibrated at varying O2 concentrations (by bubbling O2/N2 gas mixtures for 15 min). Previously, AAO samples were reduced under anaerobic conditions using a modified tonometer with a side arm containing a solution of p-methoxybenzyl alcohol, giving an alcohol/AAO molar ratio of 1.2:1.0 after mixing. After the reduction step, the tonometers were connected to the stopped-flow equipment to study AAO reoxidation. Stopped-flow traces for the oxidative half-reaction were fitted to a single-step model (A→B), as described above, or a double-step model (A→B→C), with the best fitting being chosen in each case. The bimolecular transient-state rate constants for flavin reoxidation were determined with Equation 4,

where kobs is the observed rate constant of flavin reoxidation at any given concentration of O2, and kox(app) is its apparent second-order rate constant.

For monitored enzyme turnover experiments (41), air-saturated enzyme and substrate solutions were mixed in the stopped-flow equipment, and evolution of the redox state of the flavin cofactor was monitored.

Ligand and Protein Dynamic Exploration

The AAO crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 3FIM) was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard in the Maestro software package (42). Hydrogen atoms were added to the system, and ionizable amino acid side chains were protonated assuming pH of 7.4. SiteMap (43) was then used to identify any druggable cavities, and GLIDE (44) was used to locate the most favorable docking sites. Appropriate electrostatic potential charges were derived for p-methoxybenzyl by a quantum mechanical optimization using density functional theory: the hybrid B3LYP together with the 6-31G* basis set available in Jaguar (45). We then proceeded to use PELE software for the study of ligand migration (37). PELE combines a steered stochastic approach with protein structure prediction methods, capable of projecting the migration dynamics of ligands in proteins (46, 47).

Simulations were performed on the wild-type protein and after in silico mutation of Phe-501 to tyrosine, tryptophan, and alanine. The ligands p-methoxybenzyl and O2 were placed on the surface of the protein as derived by GLIDE. Several simulations were run where the ligand is biased toward the C4a-N5 locus of the flavin ring. This is done where multiple processors share the information of a reaction coordinate. For further description of the method, see Borrelli et al. (37). In this way, we could identify the possible pathways for both ligands toward the active site. Also, O2 diffusion inside the active-site cavity in all structures was computed with PELE. The initial structure for these calculations was the final snapshot from the previous O2 migration where the ligand resides inside the cavity. The ligand is then allowed free movement, but small perturbations are employed to avoid the escape of the ligand.

RESULTS

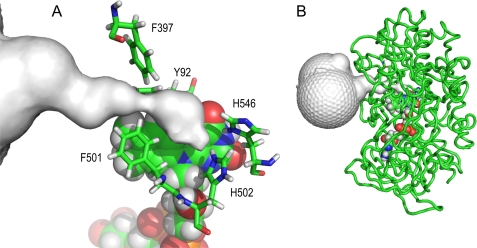

Substrate Diffusion to the AAO Active Site

The FAD cofactor position in the center of the AAO molecule and the hydrophobic funnel-shaped channel connecting the solvent with the small active-site cavity in front of the cofactor upper part are shown in Fig. 1. Two conserved histidine residues (His-502 and His-546) orient their side chains to the above cavity. Just before the active site, the access channel is constricted by a bottleneck involving Phe-501 and two other aromatic residues (Tyr-92 and Phe-397). When PELE received the task of migrating the AAO-reducing (p-methoxybenzyl alcohol) and AAO-oxidizing (O2) substrates from the wide entrance of the channel (identified by SiteMap) to the active site of the oxidized or reduced enzyme, respectively, the results differed strongly.

FIGURE 1.

Funnel-shaped channel connecting the active-site cavity to solvent in AAO. A, detail showing a bottleneck near the active-site entrance involving Phe-501, Phe-397, and Tyr-92 and the position of conserved His-502 and His-546 (re-side of the flavin ring). B, AAO backbone showing the buried FAD cofactor and the active-site access channel. The figure is based on the AAO crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 3FIM). The active-site access channel was depicted by CAVER (56). FAD is shown as Corey-Pauling-Koltun (CPK)-colored van der Waals spheres, and amino acids are shown as CPK-colored sticks.

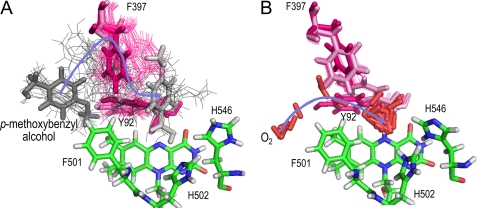

The access channel of AAO (Fig. 1A) is too narrow for p-methoxybenzyl alcohol diffusion to the active site. Considerable reorganization of the Phe-397 side chain, the most mobile among the three aromatic side chains delimiting the channel bottleneck, is required for alcohol access (Fig. 2A). The Phe-397 side chain interacts with the alcohol aromatic ring, and both move together to provide access to the active site, where the alcohol attains a catalytically relevant position. This includes the hydroxyl hydrogen and one of the Cα hydrogens of p-anisyl alcohol at a distance of 2.4–2.5 Å from the Nϵ of δ-deprotonated His-502 and the oxidized flavin N5, respectively. Such a position is consistent with the consensus mechanism in GMC oxidoreductases that involves proton transfer to a catalytic base (His-502 in AAO) and hydride transfer to the oxidized cofactor flavin (26). The PELE-predicted diffusion pathway of p-anisyl alcohol is produced above the Tyr-92 aromatic ring, which would also experience some rearrangements helping the alcohol to attain its final position, and far from the Phe-501 side chain.

FIGURE 2.

Active-site migration of AAO-reducing and AAO-oxidizing substrates: comparison of PELE pathways. A, p-methoxybenzyl alcohol entrance requires important movements of the Phe-397 and Tyr-92 side chains (alcohol in the first and last positions appears as dark- and light-gray sticks, respectively, whereas it is shown as gray lines in the other snapshots). B, O2 enters directly on the Phe-501 side chain to attain the active-site cavity of reduced AAO, and the limited side chain rearrangements observed are produced when it is already inside the cavity. O2 molecules appear as red sticks in all the snapshots. Substrate migrations were simulated by PELE (37) using the AAO crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 3FIM). The alcohol and O2 migration pathways are indicated by blue arrows. Phe-397 and Tyr-92 in the first and last snapshots are shown as magenta and light-pink sticks, respectively, whereas the other positions are shown as magenta lines. His-502, His-546, Phe-501, and FAD are shown as CPK-colored sticks.

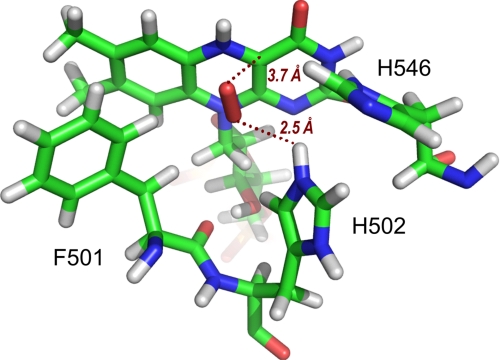

In contrast to that found for p-anisyl alcohol, the O2 access to the active site of reduced AAO, as predicted by PELE, basically follows the funnel-shaped channel depicted in the crystal structure (Fig. 1A). In this way, the pathway proceeds next to Phe-501, below Phe-397, and in front of Tyr-92, whose side chains are not significantly displaced during this first diffusion phase (Fig. 2B). Once at the active-site cavity, the O2 molecule largely explores this cavity, as described below for native AAO and three site-directed variants, and some displacement of the Phe-397 side chain is produced during this phase. A catalytically relevant final position of O2 for flavin oxidation is shown in Fig. 3. At this position, the oxygen atoms are at distances of 2.5 and 3.7 Å, respectively, from the Hϵ of His-502 and the C4a of reduced flavin, both involved in O2 reduction, and at a distance of 2.8 Å from the closest hydrogen atom of the Phe-501 side chain, whose contribution to the oxidative half-reaction is described below.

FIGURE 3.

O2 at the AAO active site. After PELE migration from the solvent region to the active site of reduced AAO (see Fig. 2B), O2 adopts a catalytically relevant position near flavin C4a and protonated His-502 Hϵ. All structures are shown as CPK-colored sticks. The image is from PELE migration on the AAO crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 3FIM).

Steady-state Studies of Site-directed Phe-501 Variants

Several AAO variants were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis of Phe-501 to investigate its effect on catalysis. The F501A, F501Y, and F501W variants showed characteristic electronic absorption spectra with a FAD maximum at 463 nm (supplemental Fig. S2), which revealed proper refolding and cofactor incorporation.

The steady-state kinetic constants of native AAO and the above three variants are shown in Table 1. Because bisubstrate kinetics were performed, both maximal alcohol (Al) and molecular oxygen (Ox) Michaelis-Menten constants (Km) and catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) are provided (by extrapolating to substrate saturation) in addition to the maximal turnover numbers (kcat). The alcohol and O2 kinetic constants for the F501Y variant were only slightly different from those of native AAO, revealing that the inclusion of a phenolic hydroxyl in the Phe-501 side chain does not significantly affect AAO catalysis. In contrast, the F501A mutation resulted in a low activity variant, whose catalytic efficiencies for p-methoxybenzyl alcohol (15-fold lower) and especially for O2 (70-fold lower) were strongly decreased. Because the F501A turnover rate was <3-fold lowered, we conclude that the main effect of the mutation concerns AAO availability of both O2 and alcohol substrates at the active site. Finally, the F501W mutation increased the AAO catalytic efficiency by almost 2-fold with respect to O2 concentration due to the nearly 3-fold decrease in Km(Ox), which suggests improved O2 availability, in contrast with the lowered alcohol affinity (due to the presence of a bulky residue at the active site) shown by both steady-state and transient-state kinetics.

TABLE 1.

Steady-state kinetic constants of native AAO and three Phe-501 variants for p-methoxybenzyl alcohol and O2 substrates

Maximal steady-state kinetic constants were determined by varying simultaneously the concentrations of p-methoxybenzyl alcohol (Al) and oxygen (Ox) in 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) at 12 °C. Rate constants were fitted to Equations 1 (native) and 2 (directed variants). Means ± S.D. are provided.

| kcat | Km(Al) | kcat/Km(Al) | Km(Ox) | kcat/Km(Ox) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | μm | s−1mm−1 | μm | s−1mm−1 | |

| AAO | 105 ± 1 | 29 ± 1 | 3620 ± 80 | 134 ± 3 | 784 ± 20 |

| F501Y | 87 ± 1 | 17 ± 1 | 5120 ± 310 | 180 ± 5 | 483 ± 13 |

| F501W | 64 ± 1 | 249 ± 5 | 257 ± 6.5 | 46 ± 2 | 1390 ± 50 |

| F501A | 40 ± 1 | 167 ± 5 | 240 ± 9 | 3600 ± 110 | 11 ± 0.5 |

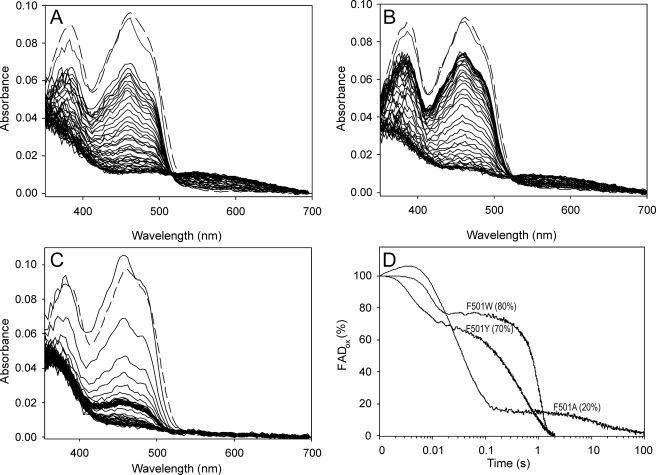

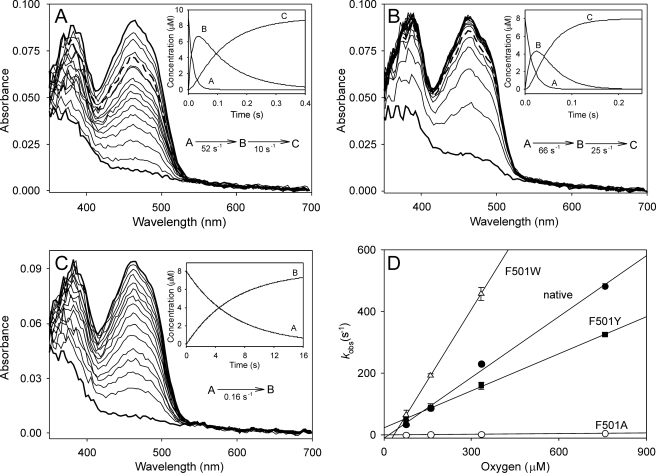

Next, the redox state of the enzyme cofactor during oxidized AAO reaction with p-methoxybenzyl alcohol under an air atmosphere was monitored using the stopped-flow diode array and single-wavelength detectors for native AAO and its site-directed variants (Fig. 4, A–C). The percentage of oxidized enzyme during turnover of native AAO and its directed variants was estimated at 462 nm, as shown in Fig. 4D using a logarithmic time scale. After an up to 4-ms lag period, which, in the slow-reacting F501A variant, includes a small absorbance increase due to enzyme-substrate complex formation, as previously described for native AAO (24), the spectra show a rapid decrease, followed by a period of relatively stable absorbance once the steady-state conditions were attained in the reaction chamber. We observed that, under the latter conditions, over 75–80% of the enzyme was in the oxidized form during steady-state turnover of native AAO and its F501W and F501Y variants (which started ∼20 ms after mixing), indicating that the reductive half-reaction is the limiting step in catalysis for these enzymes. However, the oxidative half-reaction would be the slower process in the F501A variant, with only 20% of the enzyme in the oxidized form under steady-state turnover (which, in this case, started ∼200 ms after mixing). Upon O2 consumption, full reduction of the F501Y and F501W variants occurred with the concomitant formation of a charge-transfer complex (characterized by a broad band in the 550–650 nm region), as reported for native AAO (24).

FIGURE 4.

Spectral changes during F501Y (A), F501W (B), and F501A (C) turnover with p-methoxybenzyl alcohol under an air atmosphere and time course of the above reactions followed at 462 nm (D). An aerobic solution of enzyme (∼10 μm) was reacted in the stopped-flow instrument with 0.6 mm p-methoxybenzyl alcohol (under an air atmosphere in 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) at 12 °C). The oxidized spectrum before the reaction is indicated by dashed lines, and the first reaction spectrum was recorded 2 ms after mixing. Then, spectra are shown every 20 ms in the 2–162-ms range and then every 50 ms in the 0.162–2-s range (and every 5 s in the 2–125-s range in C). Native AAO (not shown) showed spectral changes similar to those of the F501Y variant (A). The time course of the reactions (D), shown as a percentage of the oxidized form on a logarithmic time scale, revealed different enzyme oxidation degrees (20–80%) under steady-state turnover (attained after a variable-length initial decrease and before O2 exhaustion in the reaction) according to the different O2 reactivities.

Transient-state Kinetics of Phe-501 Variants

The above differences were further investigated by analyzing the reduction and reoxidation transient-state constants for the three Phe-501 variants compared with native AAO. In the first case, naturally oxidized enzymes were mixed with the reducing substrate (p-methoxybenzyl alcohol) under anaerobic conditions in the stopped-flow equipment, and the spectral changes produced were followed using the diode array and single-wavelength detectors (supplemental Fig. S3) as described previously for native AAO (24). In all cases, the observed reduction rates saturated at the highest alcohol concentrations (supplemental Fig. S3D). Accurate rate constants from the 462-nm traces were fit to Equation 3, and the transient-state constants for enzyme reduction by p-methoxybenzyl alcohol were obtained (Table 2). In general terms, the kred and Kd values from transient-state kinetics agreed with the abovementioned kcat and Km values estimated under steady-state conditions. However, a 2-fold increase in the kred value with regard to kcat was observed for the F501W variant, indicating that a step other than the reductive half-reaction must limit the reaction rate. This might be related to different steps involving product release.

TABLE 2.

Transient-state kinetic constants of AAO and three Phe-501 variants for p-methoxybenzyl alcohol and O2 substrates

Transient-state kinetic constants were determined in 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) at 12 °C. Rate constants were fitted to Equations 3 and 4 for reductive and oxidative half-reactions, respectively. Means ± S.D. are provided.

| Reductive half-reaction |

Oxidative half-reaction |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| kred | Kd | kox(app) | |

| s−1 | μm | s−1mm−1 | |

| AAO | 139 ± 16 | 26 ± 5 | 657 ± 30 |

| F501Y | 87 ± 1 | 15 ± 1 | 401 ± 9 |

| F501W | 136 ± 6 | 362 ± 45 | 1524 ± 1 |

| F501A | 35 ± 5 | 153 ± 2 | 8 ± 1 |

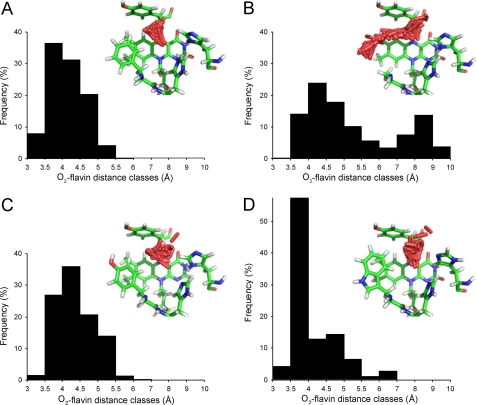

The spectral changes observed during reoxidation of native AAO and its directed variants (previously reduced by p-methoxybenzyl alcohol) are shown in Fig. 5. A two-step process (A→B→C), where B corresponds to a spectral species appearing during the reaction that does not necessarily represent a distinct enzyme intermediate, was defined after global fitting of the spectral changes from native AAO reoxidation (data not shown), and the same applies for the F501Y (changes similar to those observed for native AAO) and F501W variants. In contrast, a one-step process (A→B) was defined for the F501A variant, the meaning of which could be related to the extremely low reactivity of this variant with O2. In agreement with previous reports for native AAO (16, 24), no semiquinone intermediates were detected. In the three cases in which a two-step process was found, the first step (A→B) was the fastest and accounted for most of the amplitude of the spectral change observed. Moreover, the kobs for A→B (in the one- and two-step processes) varied with O2 concentration (Fig. 5D and supplemental Table S1), whereas the slower kobs in the two-step processes showed no oxygen dependence (the B→C step being too slow to be catalytically relevant). In contrast with that observed for the reductive half-reaction (where both alcohol kred and Kd could be obtained), the kobs showed no enzyme saturation at the highest O2 concentrations, suggesting that O2 does not bind to AAO forming an enzyme-substrate complex, and only apparent second-order reoxidation constants (kox(app)) are included in Table 2. The changes in the transient-state reoxidation constant confirmed the tendencies observed under steady-state conditions (paralleling those of kcat/Km(Ox)): the strong kox(app) decrease (>80-fold) in the F501A variant and its increase (>2-fold) in the F501W variant, and only a slightly lower kox(app) value in the F501Y variant with respect to native AAO.

FIGURE 5.

Oxidative half-reaction: spectral changes during reaction of reduced AAO F501Y (A), F501W (B), and F501A (C) variants with O2 and reoxidation dependence on concentration (D). The spectral changes were followed after mixing ∼9 μm reduced enzyme with 0.1 m phosphate (pH 6) containing 76 μm O2 in the stopped-flow spectrophotometer at 12 °C. Spectra are shown after different reaction times (2, 9, 17, 24, 32, 40, 47, 55, 63, 70, 86, 93, 109, 117, 125, 150, 175, 200, and 250 ms in A and B and 40, 860, 1680, 2450, 3320, 4140, 5780, 6590, 7410, 8230, 9050, 10,700, 12,330, 13,970, and 15,600 ms in C). The insets show the simulated concentration dependence of the spectral species obtained after globally fitting the experimental data to one-step (A→B) and two-step (A→B→C) models. Spectra where species A (bottom thick lines), B (thick dashed lines in A and B), and C (top thick lines) were predominant are indicated in the main panels. Native AAO (not shown) showed spectral changes similar to those of the F501Y variant (A). To study the reoxidation dependence on O2 concentration (D), samples of reduced AAO and its F501W, F501Y, and F501A variants were mixed with buffer equilibrated at 76, 160, 334, and 760 μm O2 under the same conditions described above, and the fastest observed reoxidation rates (kobs corresponding to the A→B step) were estimated at 462 nm.

Phe-501 Mutations and O2 Diffusion inside the Active Site

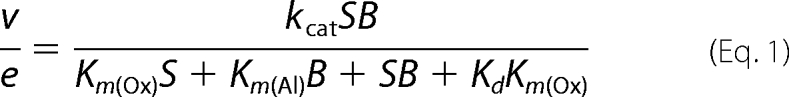

Free diffusion of O2 inside the active-site cavity of the AAO crystal structure and its (in silico mutated) F501A, F501Y, and F501W variants was analyzed by PELE, looking for differences in O2 population after mutations. Approximately 1000 positions were computed in each case, and the distances between C4a and the O2 atoms were estimated and distributed in frequency classes (Fig. 6). The frequency distribution was similar in the F501Y variant and native AAO, although the average distance was shorter for AAO (4.1 Å compared with 4.4 Å). However, significantly different frequency distributions were obtained for the F501A and F501W variants. The former was clearly bimodal (with predominant positions at 4.5 and 8.1 Å), whereas the latter showed >60% of the O2 positions at a distance of 3–4 Å from C4a.

FIGURE 6.

O2-flavin distance classes after substrate diffusion by PELE corresponding to different O2 (red sticks) distributions inside the active site. A, native AAO; B, F501A variant; C, F501Y variant; D, F501W variant. The O2 substrate molecule was placed near flavin C4a, and PELE (37) was instructed to diffuse it freely inside the active-site cavity (by using low temperatures and small perturbations). The distances between flavin C4a and the O2 atoms were estimated in ∼1000 positions, and the values obtained were distributed in 10 frequency classes. O2 distribution is shown in the different images, where nearly 200 selected O2 positions are shown, together with the cofactor flavin ring and Tyr-92 (top), His-546 (right), His-502 (middle), and Phe/Ala/Tyr/Trp-501 (left) (as CPK-colored sticks).

DISCUSSION

Substrate Diffusion to the AAO Active Site

The active sites of other GMC oxidoreductases are exposed to the solvent, as found in the glucose oxidase monomer crystal structure (48), although in the dimeric structure, a second subunit partially covers the access to the active site. The situation is similar in the tetrameric pyranose-2 oxidase (49). By contrast, the active site of AAO (a monomeric enzyme) is deeply buried and inaccessible due to the presence of two new structural motifs compared with related enzymes (23). The larger motif includes two helices that are absent in both glucose oxidase and choline oxidase, whereas the second motif is present in choline oxidase, which has an active site that is less exposed compared with glucose oxidase, although more accessible compared with AAO.

The above structural motifs delimit a funnel-shaped channel characterized by a narrow bottleneck formed by the Tyr-92, Phe-397, and Phe-501 side chains that limits the diffusion of substrates to the AAO active site. In aromatic alcohol access, Phe-397 in the loop that is absent in glucose oxidase (homologous to Phe-357 in choline oxidase) plays a crucial role, interacting with the substrate aromatic ring and helping it to attain the active site by side chain oscillations, as described in detail by Hernández-Ortega et al. (27). Side chain mobility (including Phe-357) has been also reported at the surface opening of the choline oxidase active site (50).

The O2 diffusion simulations performed here with PELE (37) revealed that this diatomic molecule basically follows the narrow access channel found in the AAO crystal structure, in contrast with the aromatic alcohol diffusion pathway that, after side chain rearrangements, overcomes the channel bottleneck by passing on the Tyr-92 side chain. Therefore, Phe-397 side chain displacements are not necessary along the O2 diffusion compared with the alcohol diffusion.

The results showing O2 access to the AAO active site through a (narrow) hydrophobic channel are in agreement with recent reports describing specific (unique or multiple) O2 diffusion channels in cholesterol oxidase (33, 34), d-amino acid oxidase (35), and other flavo-oxidases (32), in contrast with the traditional hypothesis assuming free diffusion of O2 through proteins. The existence of channel gates has also been described in some of the above flavo-oxidases, e.g. in cholesterol oxidase (51). Moreover, in some flavoenzymes, the existence of residues collecting and guiding O2 toward the active site has been suggested, such as Phe-266 at the active-site entrance in p-hydroxyphenylacetate hydroxylase (32).

In d-amino acid oxidase, O2 and the reducing amino acid substrate react with the flavin ring at opposite sides (si and re, respectively) and access the cofactor by different pathways (35). In contrast, in AAO (and glucose oxidase), both oxidizing and reducing substrates would occupy nearly the same position for catalysis (at the re-side of flavin). However, the PELE predictions revealed that both substrates share only the most external part of the entrance pathway in AAO. Then, transient modifications of the channel, implying large oscillations of the Phe-397 side chain, are required for alcohol substrates to attain the active site, whereas no significant side chain rearrangements were observed during O2 access. (supplemental Movie S1 shows the successive diffusion of a polyunsaturated alcohol substrate and O2 to the active site of AAO as predicted by PELE). If the aldehyde product remains at the active site when O2 arrives (ternary reaction mechanism), some mobility of the product molecule is required for flavin reoxidation by O2 (as shown in supplemental Movie S1).

Phe-501 Involvement in Flavin Reoxidation

When the aromatic ring of Phe-501 was removed or substituted with other aromatic rings, some significant changes in the AAO steady-state and transient-state kinetic constants were produced, revealing that this residue strongly contributes to flavin reoxidation. In the F501A variant, alcohol oxidation was negatively affected (∼15-fold lower efficiency), with the main effect being on binding. However, the most important effect of the F501A mutation was on O2 reactivity, with 70–80-fold lower kinetic constants (kcat/Km(Ox) and kox(app)). The strong drop in O2 reactivity is also reflected in the low oxidation degree during delayed steady-state turnover (only ∼20% for F501A). These results, together with the similar O2 reactivity of F501Y and the improved reactivity of the F501W variant compared with the native enzyme, suggest that a bulky residue at this position is required for efficient flavin reoxidation in AAO. The presence of an aromatic residue at this position also contributes, although to a lower extent, to alcohol oxidation by AAO, as revealed by the similar alcohol efficiency of F501Y and the lower efficiency of F501A. It is interesting that the residues homologous to AAO Phe-501 in the related glucose oxidase and choline oxidase are two tyrosine residues, although their involvement in flavin reoxidation has not been reported to date.

The alcohol reactivity of the F501W variant was reduced due to decreased substrate binding (14-fold higher Kd), probably involving steric hindrances, whereas kred was not affected. More interestingly, this variant showed 2-fold higher reactivity with O2 (under both steady-state and transient-state conditions) than native AAO, which already has one of the highest O2 reactivities reported in flavo-oxidases (30). This occurred despite the fact that O2 diffusion to the active site in the F501W variant is made more difficult by the indolic side chain. Recently, an AAO enzyme has been characterized from another white rot fungus (52) that has a tryptophan residue homologous to P. eryngii AAO Phe-501 (53), showing that natural variants with other aromatic residues at this position also exist in nature. Despite that changes in the redox potential of AAO by site-directed mutagenesis of Phe-501 have been reported (±40 mV) (54), they hardly account for the reactivity changes presented here. However, the steady-state and transient-state kinetic data obtained strongly suggest that the increased O2 reactivity of the F501W variant and the decreased reactivity of the F501A variant largely depend on the increased/decreased ability of the enzyme for properly positioning the O2 molecule during the oxidative half-reaction. How the presence of phenylalanine, tyrosine, alanine, or tryptophan at position 501 of AAO affects the position of O2 at the AAO active site is clarified by the substrate diffusion simulations discussed below.

Different O2 distributions inside the AAO active site were provided by PELE, with the percentage of oxygen atoms populating the region at 3–4 Å from flavin C4a being significantly different in native AAO (44%) and the F501A (14%), F501Y (28%), and F501W (61%) variants. This suggests that once O2 has reached the active site, the bulky aromatic side chains at position 501 in native AAO and its F501Y and F501W variants help it to attain a catalytically relevant position near flavin C4a and His-502 Hϵ involved in reoxidation (supplemental Fig. S1) (36). The high O2 reactivity of the F501W variant (>1500 s−1 mm−1 based on kox(app)) is in agreement with the high oxygen population at 3.5–4.0 Å from flavin C4a predicted by PELE.

Interestingly, the main difference between the active site of flavocytochrome b2 (Protein Data Bank code 1FCB), which shows nearly no reactivity with O2, and glycolate oxidase (Protein Data Bank code 1AL7), which has a high rate constant (nearly 106 s−1 m−1), is a leucine residue instead of tryptophan near the flavin (30). Moreover, it has been suggested in the related choline oxidase that Val-464, located at a two-residue distance (Val-464–Tyr-465–His-466) from His-466, homologous to AAO His-502 and also involved in catalysis (26, 27), would provide a non-polar site guiding O2 to flavin, as revealed by the decreased O2 reactivity of the V464A variant (55).

In this study, we have shown how a hydrophobic channel provides O2 access to the AAO buried active site without significant side chain rearrangement being required to overcome the bottleneck formed by Phe-501 and two other aromatic residues. This residue is important for enzyme reoxidation, as shown by site-directed mutagenesis, kinetic, and computational data. These studies show how O2 reactivity can be increased in a GMC oxidoreductase by introducing, at the position contiguous to the catalytic histidine (AAO His-502), a residue improving O2 positioning at the active-site cavity, as demonstrated with the F501W variant of fungal AAO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the Barcelona Supercomputing Center for computational resources.

This work was supported in part by Spanish Projects BIO2008-01533 and BIO2010-1493 (to A. T. M. and M. M., respectively) and by the PEROXICATS (KBBE-2010-4-265397) and PELE (ERC-2009-Adg 25027) European Projects (to A. T. M. and V. G., respectively).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3, Table S1, and Movie S1.

- AAO

- aryl-alcohol oxidase

- PELE

- Protein Energy Landscape Exploration

- CPK

- Corey-Pauling-Koltun.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ragauskas A. J., Williams C. K., Davison B. H., Britovsek G., Cairney J., Eckert C. A., Frederick W. J., Jr., Hallett J. P., Leak D. J., Liotta C. L., Mielenz J. R., Murphy R., Templer R., Tschaplinski T. (2006) Science 311, 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martínez A. T., Speranza M., Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Ferreira P., Camarero S., Guillén F., Martínez M. J., Gutiérrez A., del Río J. C. (2005) Int. Microbiol. 8, 195–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldrian P., Valásková V. (2008) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 501–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martinez D., Challacombe J., Morgenstern I., Hibbett D., Schmoll M., Kubicek C. P., Ferreira P., Ruiz-Duenas F. J., Martinez A. T., Kersten P., Hammel K. E., Vanden Wymelenberg A., Gaskell J., Lindquist E., Sabat G., Bondurant S. S., Larrondo L. F., Canessa P., Vicuna R., Yadav J., Doddapaneni H., Subramanian V., Pisabarro A. G., Lavín J. L., Oguiza J. A., Master E., Henrissat B., Coutinho P. M., Harris P., Magnuson J. K., Baker S. E., Bruno K., Kenealy W., Hoegger P. J., Kües U., Ramaiya P., Lucas S., Salamov A., Shapiro H., Tu H., Chee C. L., Misra M., Xie G., Teter S., Yaver D., James T., Mokrejs M., Pospisek M., Grigoriev I. V., Brettin T., Rokhsar D., Berka R., Cullen D. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1954–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martinez D., Larrondo L. F., Putnam N., Gelpke M. D., Huang K., Chapman J., Helfenbein K. G., Ramaiya P., Detter J. C., Larimer F., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B., Berka R., Cullen D., Rokhsar D. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martínez A. T., Rencoret J., Nieto L., Jiménez-Barbero J., Gutiérrez A., del Río J. C. (2011) Environ. Microbiol. 13, 96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martínez A. T., Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Martínez M. J., Del Río J. C., Gutiérrez A. (2009) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hammel K. E., Cullen D. (2008) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Martínez A. T. (2009) Microb. Biotechnol. 2, 164–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kersten P., Cullen D. (2007) Fungal Genet. Biol. 44, 77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bourbonnais R., Paice M. G. (1988) Biochem. J. 255, 445–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guillén F., Martínez A. T., Martínez M. J. (1990) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32, 465–469 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muheim A., Waldner R., Leisola M. S. A., Fiechter A. (1990) Enzyme Microb. Technol. 12, 204–209 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martínez A. T., Camarero S., Guillén F., Gutiérrez A., Muñoz C., Varela E., Martínez M. J., Barrasa J. M., Ruel K., Pelayo M. (1994) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 13, 265–274 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferreira P., Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Martínez M. J., van Berkel W. J., Martínez A. T. (2006) FEBS J. 273, 4878–4888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferreira P., Medina M., Guillén F., Martínez M. J., Van Berkel W. J., Martínez A. T. (2005) Biochem. J. 389, 731–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Varela E., Martínez A. T., Martínez M. J. (1999) Biochem. J. 341, 113–117 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gutiérrez A., Caramelo L., Prieto A., Martínez M. J., Martínez A. T. (1994) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 1783–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Jong E., Field J. A., Dings J. A., Wijnberg J. B., de Bont J. A. (1992) FEBS Lett. 305, 220–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guillén F., Evans C. S. (1994) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 2811–2817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martínez A. T. (2002) Enzyme Microb. Technol. 30, 425–444 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Varela E., Jesús Martínez M., Martínez A. T. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1481, 202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernández I. S., Ruíz-Dueñas F. J., Santillana E., Ferreira P., Martínez M. J., Martínez A. T., Romero A. (2009) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1196–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira P., Hernandez-Ortega A., Herguedas B., Martínez A. T., Medina M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24840–24847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferreira P., Hernández-Ortega A., Herguedas B., Rencoret J., Gutiérrez A., Martínez M. J., Jiménez-Barbero J., Medina M., Martínez A. T. (2010) Biochem. J. 425, 585–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gadda G. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 13745–13753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hernández-Ortega A., Borrelli K., Ferreira P., Medina M., Martínez A. T., Guallar V. (2011) Biochem. J. 436, 341–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roth J. P., Klinman J. P. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 62–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klinman J. P. (2007) Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mattevi A. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 276–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Massey V. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22459–22462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baron R., Riley C., Chenprakhon P., Thotsaporn K., Winter R. T., Alfieri A., Forneris F., van Berkel W. J., Chaiyen P., Fraaije M. W., Mattevi A., McCammon J. A. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10603–10608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen L., Lyubimov A. Y., Brammer L., Vrielink A., Sampson N. S. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 5368–5377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piubelli L., Pedotti M., Molla G., Feindler-Boeckh S., Ghisla S., Pilone M. S., Pollegioni L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24738–24747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saam J., Rosini E., Molla G., Schulten K., Pollegioni L., Ghisla S. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 24439–24446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hernández A., Ferreira P., Martínez M. J., Romero A., Martínez A. T. (2008) in Flavins and Flavoproteins 2008 (Frago S., Gómez-Moreno C., Medina M. eds) pp. 303–308, Prensas Universitarias, Zaragoza, Spain [Google Scholar]

- 37. Borrelli K. W., Vitalis A., Alcantara R., Guallar V. (2005) J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1, 1304–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Ferreira P., Martínez M. J., Martínez A. T. (2006) Protein Expr. Purif. 45, 191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Macheroux P. (1999) in Flavoprotein Protocols (Chapman S. K., Reid G. A. eds) pp. 1–7, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fraaije M. W., van Berkel W. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18111–18116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gibson Q. H., Swoboda B. E., Massey V. (1964) J. Biol. Chem. 239, 3927–3934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schrödinger, LLC (2011) Maestro, Version 9.2, Schrödinger LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halgren T. (2007) Chem. Biol. Drug Design 69, 146–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Friesner R. A., Banks J. L., Murphy R. B., Halgren T. A., Klicic J. J., Mainz D. T., Repasky M. P., Knoll E. H., Shelley M., Perry J. K., Shaw D. E., Francis P., Shenkin P. S. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 1739–1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schrödinger LLC(2011) Jaguar, Version 7.8, Schrödinger LCC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 46. Borrelli K., Cossins B., Guallar V. (2010) J. Comp. Chem. 31, 1224–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guallar V., Lu C., Borrelli K., Egawa T., Yeh S. R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 3106–3116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hecht H. J., Kalisz H. M., Hendle J., Schmid R. D., Schomburg D. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 229, 153–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hallberg B. M., Leitner C., Haltrich D., Divne C. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 341, 781–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xin Y., Gadda G., Hamelberg D. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 9599–9605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coulombe R., Yue K. Q., Ghisla S., Vrielink A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30435–30441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Romero E., Ferreira P., Martínez A. T., Martínez M. J. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794, 689–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Romero E., Martínez A. T., Martínez M. J. (2010) in Proceedings of Oxidative Enzymes as Sustainable Industrial Biocatalysts, Santiago de Compostela, September 14–15, 2010 (Feijoo G., Moreira M. T. eds) pp. 86–91, University of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain [Google Scholar]

- 54. Munteanu F. D., Ferreira P., Ruiz-Dueñas F. J., Martínez A. T., Cavaco-Paulo A. (2008) J. Electroanal. Chem. 618, 83–86 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Finnegan S., Agniswamy J., Weber I. T., Gadda G. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 2952–2961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Petrek M., Otyepka M., Banás P., Kosinová P., Koca J., Damborský J. (2006) BMC Bioinformatics 7, 316–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.