Background: Prions occur in the form of various strains, which show distinct cell tropisms.

Results: Swainsonine and other inhibitors of N-glycosylation impede prion infection in a strain- and cell-specific manner.

Conclusion: Misglycosylation of cell proteins other than the prion protein modulates susceptibility to prion strains.

Significance: Inhibitors of N-glycosylation allow differentiation between prions strains and implicate involvement of host factors in prion replication.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Glycosylation Inhibitors, Molecular Cell Biology, Neurodegenerative Diseases, Prions, Prion Strains

Abstract

Neuroblastoma-derived N2a-PK1 cells, fibroblastic LD9 cells, and CNS-derived CAD5 cells can be infected efficiently and persistently by various prion strains, as measured by the standard scrapie cell assay. Swainsonine, an inhibitor of Golgi α-mannosidase II that causes abnormal N-glycosylation, strongly inhibits infection of PK1 cells by RML, 79A and 22F, less so by 139A, and not at all by 22L prions, and it does not diminish propagation of any of these strains in LD9 or CAD5 cells. Misglycosylated PrPC formed in the presence of swainsonine is a good substrate for conversion to PrPSc, and misglycosylated PrPSc is fully able to trigger infection and seed the protein misfolding cyclic amplification reaction. Distinct subclones of PK1 cells mediate swainsonine inhibition to very different degrees, implicating misglycosylation of one or more host proteins in the inhibitory process. The use of swainsonine and other glycosylation inhibitors described herein enhances the ability of the cell panel assay to differentiate between prion strains. Moreover, as shown elsewhere, the susceptibility of prions to inhibition by swainsonine in PK1 cells is a mutable trait.

Introduction

The “protein-only” hypothesis states that prions consist of PrPSc, a conformational isomer of the ubiquitous host glycoprotein PrPC, and that their replication comes about by PrPSc-directed conversion of PrPC to PrPSc. The seeding model proposes that PrPC is in equilibrium with PrPSc (or a precursor thereof); however, with the equilibrium strongly favoring PrPC, and that PrPSc is only stabilized when it forms an aggregate containing a critical number of monomers. Once such a seed is present, monomer addition ensues rapidly (1, 2).

PrPC is attached to the outer surface of the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor and may carry two, one, or no asparagine-linked glycans, of which there are 52 or more variants (3, 4). PrPC is highly susceptible to proteinase K (PK) digestion; PrPSc species may be either PK-resistant (rPrPSc) or PK-sensitive (sPrPSc) (5–10).

Prions occur in the form of distinct strains, originally characterized by the incubation time and the neuropathology they elicit in a particular host (11). The finding that several different strains can be propagated indefinitely in hosts homozygous for the PrP5 gene (Prnp) led to the proposal that strain-specific properties are determined by some feature of the pathogenic PrP other than its amino acid sequence, such as its conformation (12–14). Within the framework of the protein-only hypothesis, each strain is assumed to be associated with a different isoform of PrPSc that can convert PrPC to a likeness of itself (15, 16). A detailed analysis of the kinetics underlying the propagation of yeast prion strains has been reported (17).

Not all cell lines are susceptible to chronic infection by prions (18–20). We have isolated several distinct murine cell lines that are susceptible to RML and 22L as well as other prion strains, in particular the PK1 and R33 lines, derived from the neuroblastoma line N2a (21), LD9 from the fibroblastic line L929 (22), and CAD5 from Cath.a-differentiated (CAD) cells (22). We have developed the cell panel assay, which allows the distinction of several prion strains, in particular RML, 22L, ME7, and 301C, by determining their cell tropism using the standard scrapie cell assay (SSCA) (21, 23). Mouse-adapted 22L and ME7 prions were derived from scrapie-infected sheep and 301C from bovine spongiform encephalopathy-infected cattle, whereas RML is thought to originate from scrapie-infected goats (24).

Swainsonine (swa), an inhibitor of Golgi α-mannosidase II, leads to the replacement of asparagine-linked, Endo-H-resistant complex glycoproteins by Endo-H-sensitive, mannose-rich hybrid-type complex glycoproteins (supplemental Fig. S1) (25–27). We found that swa inhibited infection of PK1 cells by RML, 79A and 22F about 99%, by 139A prions about 90% but did not inhibit infection by 22L prions nor did it affect propagation of RML or any of the aforementioned strains in LD9 or CAD5 cells. Other inhibitors of N-glycosylation, kifunensine and castanospermine, which inhibit α-mannosidase I and α-glucosidase, respectively, also inhibited prion infection in both a strain-specific and cell-specific manner but were not studied in further detail. Thus, these inhibitors extend the ability of the cell panel assay to discriminate between prions strains. In addition, acquisition of swa sensitivity by 22L prions on being transferred from brain to PK1 cells (28) or from R33 to PK1 cells (29) allowed demonstration of prion adaptation to the environment. Furthermore, the discovery that swa-sensitive prion populations can acquire swa resistance when propagated in the presence of the drug revealed that pathogens devoid of nucleic acid can undergo Darwinian evolution (28).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Prion Preparations

The RML strain (RML I856-II) was obtained from the Medical Research Council Prion Unit, University College London, and propagated in CD1 mice. ME7 and 22L strains were from the Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy Resource Centre, Compton, Newbury, UK, and were propagated in C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Frozen brains were homogenized for 10 s in PBS (9 ml per g) using a hand-held Ultramax T18 basic homogenizer (IKA Works Inc., Bloomington, NC) at 20,000–25,000 rpm. Homogenates were stored in small aliquots at −80 °C. Thawed homogenates were re-homogenized by passing through a 28-gauge needle; they were not centrifuged at any stage. The titers, determined by mouse bioassay, in LD50 units/g brain, were 108.8 for RML, 108.3 for ME7, and 108.3 for 22L. To prepare cell lysates, 2.5 × 107 cells suspended in 1 ml of PBS (containing complete protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science)) were frozen in liquid nitrogen, thawed three times, and passed eight times through a 28.5-gauge needle. RML PrP(27–30) was prepared by diluting 10% RML brain homogenate to 2.5% in PBS, 0.5% octyl glucoside and digesting with 100 μg of proteinase K (PK) (Roche Applied Science, 2.37 units (hemoglobin)/mg) for 1 h at 50 °C. Digestion was terminated by adding PMSF to 2 mm.

Cell Lines

The isolation of N2a-PK1 cells (21) and CAD5 and LD9 cells (22) has been described. All cell lines were maintained in OBGS (Opti-MEM® (Invitrogen), 9% (and more recently, 4.5%) bovine growth serum (BGS) (HyClone, Logan, UT), 90 units of penicillin/ml, 90 μg of streptomycin/ml (Invitrogen)). For subcloning, PK1-CAB19 cells (22) grown in OBGS were resuspended and seeded at a density of 100 cells per 15-cm dish. After about 10 days, individual colonies were transferred to the wells of 96-well plates. Duplicate 96-well plates were generated, and one set was screened by the SSCA for response to 5 × 10−6 RML. The highest responding clones were expanded to 107 cells in 15-cm dishes and frozen down in aliquots in OBGS, 6% DMSO.

SSCA

The SSCA was essentially performed as described previously (21, 23) except that 5000 (rather than 20,000) prion-susceptible cells were exposed to a serial dilution of the prion preparation for 4 days (rather than 3 days), in the presence or absence of 2 μg swa/ml. The cells were split 1:7 into OBGS and, after reaching confluence, were split two more times. After reaching confluence, 20,000 cells were deposited on the membrane of a Multiscreen IP96-well 0.45-μm filter plate (Millipore, Danvers, MA), and rPrPSc-positive cells were identified by PK-ELISA. In short, after drying at 50 °C, the samples were lysed, digested with PK, denatured with guanidinium thiocyanate, and exposed to anti-PrP antibody D18 (30) and then to an AP-coupled anti-IgG antibody. After color development, spots were counted using the Zeiss KS Elispot system, all as described previously (21, 23). When the SSCA was performed in the presence of swa (Logan Natural Products) or mannostatin A (Toronto Research Chemicals or Enzo Life Sciences), the inhibitors were present during the entire assay.

Standard PK Digestion

The samples, in PBS, 0.5% Triton, were adjusted to 3 mg of protein/ml and digested with PK (Roche Applied Science, 20.2 mg/ml; volume activity (hemoglobin) 967 units/ml; specific activity (hemoglobin) 47.9 units/ml) at 20 μg/ml. Samples with a lower concentration of protein were digested with a proportionately lower concentration of PK (1:150 ratio of PK to protein). Digestion was for 1 h at 37 °C; the reaction was stopped with 2 mm PMSF.

Western Blot Analysis of Endo-H-digested PrP

Cell lysate (300 μg of protein in 120 μl of 1% SDS, 80 mm DTT) was denatured at 100 °C for 10 min. Aliquots (60 μg) were incubated with or without 1500 units of Endo-H (500 units/μl, New England Biolabs) in 50 mm sodium citrate, pH 5.5, for 1.5 h at 37 °C. To generate unglycosylated PrP as reference, 60-μg samples were digested with 1500 units of PNGaseF (New England Biolabs) in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 1% Nonidet P-40 (final volume, 30 μl) for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Digestions were terminated by adding 10 μl of 4× XT MES sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and heating 10 min at 100 °C. For Western blotting, 30-μg aliquots were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (4–12% polyacrylamide, Bio-Rad Criterion System precast gels) 1 h at 120 V and transferred to PVDF Immobilon membranes (Millipore) by semi-dry transfer (Bio-Rad). After exposure to 160 ng/ml D18 anti-PrP antibody (30) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary anti-human antibody (16 ng/ml, Southern Biotech), chemiluminescence was induced by ECL-Plus (Pierce) and recorded by CCD imaging (BioSpectrum AC Imaging System; UVP).

Flow Cytometry

To determine cell surface PrP, cells were grown for 11 days with and without 2 μg of swa/ml and resuspended in fresh medium, and 106 cells were pelleted at 500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Following resuspension in 0.5 ml of FB (1× PBS containing 1% BGS), the cells were incubated on ice for 20 min in FB containing 2.2 μg/ml anti-PrP antibody D18, washed twice by centrifugation and resuspension in fresh FB, and incubated in 0.5 ml of FB containing 8 μg of Alexa488-linked anti-human IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen)/ml for 20 min on ice in the dark. Following two washes in FB, fluorescent cells were analyzed on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), gated for singlets.

Inhibition of PrPC Expression by siRNA

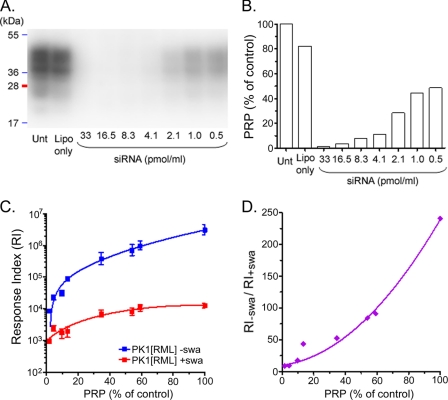

PrP expression was transiently knocked down in PK1 cells with a serial dilution of siRNA against PrP. siRNA directed against PrP (Qiagen mM PrnP 3 SI01389549) at 100 pmol/ml in Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) 1:100 in Opti-MEM® was incubated for 20 min at ambient temperature, serially diluted 1:2 with Opti-MEM®, and 100 μl/well of each dilution was placed into wells of 96-well plates. A Lipofectamine-only control was included. To each well 20,000 PK1 cells were added, and after 24 h, the medium was replaced with OBGS. After a further 24 h, the cells from 24 wells of each siRNA dilution were pooled (to give about 2 × 106 cells) and subjected to the SSCA, with or without 2 μg/ml swa, 5000 cells in sextuplicate for each condition. The remaining cells were suspended in PBS + protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) at 107 cells/ml and lysed, and the relative PrPC levels were determined by Western blotting as described above.

Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification (PMCA)

PMCA was carried out by subjecting a PrPC-containing substrate (uninfected brain homogenate or cell lysate), primed with a PrPSc “seed” (prion-infected brain homogenate or cell lysate), to repeated cycles of sonication and incubation. “Brain substrate” was prepared as described previously (31) but not subjected to centrifugation. PMCA using cell lysates as substrate has been described (32). To prepare “cell substrate,” PK1 cells were grown for 7 days in the presence or absence of 2 μg of swa/ml, collected by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, suspended at 4 × 107 cells/ml, and lysed in cell conversion buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture (PIC, Roche Applied Science) in 1× PBS). Substrates were stored at −80 °C. “RML cell seed” was prepared from PK1[RML] cells grown for 7 days in the presence or absence of 2 μg of swa/ml. Cells were suspended at 2.5 × 107/ml in lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS), lysed by three cycles of rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing, and passed eight times through a 22-gauge needle. The PrPC content of the “+swa” and “−swa” lysates, as measured by Western blot analysis after PNGase treatment, did not differ significantly (one-way analysis of variance, p < 0.01). “Cell PMCA” reaction mixtures consisted of 445.5 μl of cell substrate or brain homogenate as control, seeded with 4.5 μl of 6.25 × 10−2 RML brain homogenate in 1× PBS. “Brain PMCA” reaction mixtures consisted of 445.5 μl of brain substrate seeded with 4.5 μl of 6 × 10−3 RML brain homogenate in 1× PBS or 4.5 μl of cell lysate adjusted to contain the same rPrPSc level as the brain homogenate. For PMCA, 80-μl aliquots of the reaction mixtures were dispensed into 200-μl PCR tubes (Axygen) containing 37 ± 3 mg of 1.0-mm Zirconia/Silica beads (Biospec Products), and samples were subjected to cycles of 20 s of sonication and 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, for 0, 2, 4, 8, or 12 h, using a Misonix 3000 sonicator at the 8.5 power setting. All reactions were performed in triplicate. To measure rPrPSc amplification, 40-μl aliquots were incubated with 40 μg of PK (Roche Applied Science)/ml for 1 h at 56 °C with shaking. Digestion was terminated by adding 12.5 μl of 4× XT-MES sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and heating 10 min at 100 °C. Aliquots (10 μl) were run through SDS-polyacrylamide gels (4–12% polyacrylamide, Bio-Rad Criterion System precast gels) for 10 min at 80 V followed by 1 h at 150 V. Proteins were transferred to PVDF Immobilon membranes (Millipore) by wet transfer (Bio-Rad), and PrP was visualized by incubation with the anti-PrP humanized antibody D18 (0.5 μg/ml) and HRP-conjugated anti-Hu IgG secondary antibody (40 ng/ml, Southern Biotech). Chemiluminescence was induced by ECL-Plus (Pierce) and recorded by CCD imaging (BioSpectrum AC Imaging System; UVP). Densitometric data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel and plotted with GraphPad Prism. PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Fermentas) was run as molecular weight marker.

Confocal Microscopy of Cells Stained for rPrPSc and Cell Surface Proteins

Cells were grown on glass culture slides (BD Biosciences) in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml swa for 3 days, after which cells were exposed to 10−3 RML or 22L-infected brain homogenate. At 4, 24, or 48 h after infection, cells were processed and stained for rPrPSc essentially as described (33). Unless stated otherwise, procedures were carried out at room temperature. Cells were treated with 50 μg of thermolysin/ml in PBS for 30 min at 37 °C, which removes PrPC at the cell surface but does not degrade rPrPSc or dislodge the cells (34).6 Cells were washed once with cold PBS and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with 1 μg of EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-biotin/ml (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) in PBS to biotinylate cell surface proteins. The cells were washed with PBS containing 0.1 m glycine, once with PBS, and fixed 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% digitonin in PBS. Slides were incubated 10 min in 6 m guanidine hydrochloride followed by two washes in PBS, 1% BSA. After blocking for 30 min in PBS, 1% BSA, slides were stained at 37 °C with 0.7 μg of monoclonal antibody D18/ml for 30 min, followed by Alexa488-conjugated anti-human IgG and Alexa635-conjugated streptavidin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min. Slides were mounted in Prolong Gold (Molecular Probes) and viewed with an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope using a 100× oil-immersion objective. Cells were imaged throughout their entire vertical extent in 0.2-μm-thick optical sections. Three-dimensional rPrPSc objects were quantified using the three-dimensional Object Counter plugin (http://rsbweb.nih.gov) for Mac Biophotonics ImageJ for microscopy. An “rPrPSc object” was defined as having a minimum D18 fluorescence intensity over a contiguous region at least 0.025 μm3 in size; the minimum intensity was set such that no events were identified in uninfected cells thermolysin-digested, biotinylated, fixed, stained, and imaged in parallel. rPrPSc objects with coincident biotin signals were scored as being extracellular. Images were constructed from maximum intensity Z-projections of at least 15 sections from about 1 to 4 μm from the culture surface.

Pulse Labeling of rPrPSc with 35S-Labeled Amino Acids

PK1 or LD9 cells (106 in 10-cm dishes, in Opti-MEM®-4.5% BGS) were exposed to a 10−4 dilution of RML-infected brain homogenate. After 4 days, the medium was replaced with fresh medium with or without 2 μg of swa/ml, and the cells were propagated for 4 more days, with an additional medium change on day 7. Eight days after infection, cells were starved of methionine and cysteine for 1 h using Pulse Medium (DMEM lacking methionine and cysteine (Invitrogen) with 1% dialyzed BGS), exposed to Pulse Medium supplemented with 0.2 mCi/ml 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine (EXPRE35S35S protein labeling mix, [35S], PerkinElmer Life Sciences) for 2 h, washed with PBS, and incubated in normal OBGS medium. Cells were harvested at the times indicated, washed with 10 ml of PBS, resuspended, and lysed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate). rPrPSc was precipitated with sodium phosphotungstic acid as described previously (35). The pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer containing 5 mg of BSA/ml. The samples were digested with 80 μg of PK/ml for 1 h at 37 °C, precipitated with methanol/chloroform, and denatured in 200 μl of 3 m guanidinium thiocyanate in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8. After another methanol/chloroform precipitation, the denatured rPrPSc was resuspended in 1 ml of DLPC buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, 150 mm NaCl, 2% Sarkosyl, 0.4% l-α-lecithin), incubated with D18 antibody (5 ng/ml) overnight at 4 °C, and exposed to 200 μl of protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen) for 90 min at 4 °C with shaking. The beads were washed once with 1 ml of DLPC buffer for 30 min, once with TN-1% S buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, 0.5 m NaCl, 1% Sarkosyl) for 30 min, and five times with TN-1% S buffer for 10 min, all at 4 °C. Tubes were changed after each washing step to minimize carry-over of background radioactivity. The beads were boiled in 200 μl of 1× Glycoprotein Denaturation Buffer (New England Biolabs) for 10 min at 100 °C and deglycosylated with PNGaseF according to the manufacturer's protocol (New England Biolabs). Samples were precipitated with methanol/chloroform and resuspended in 20 μl of 1× XT-MES sample buffer (Roche Applied Science). One aliquot was subjected to Western blot analysis (at 1:20 dilution), as described above, to determine the recovery of rPrPSc, and another aliquot was run through an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (4–12% bis-tris Criterion gel, Bio-Rad). The gel was dried for 2 h in a Bio-Rad gel dryer in a vacuum generated by a water aspirator, exposed to a phosphorscreen (Storage Phosphor Screen, GE Healthcare) for 1 or 2 days, and imaged with a Storm 860 scanner (Amersham Biosciences).

RESULTS

Strain- and Cell-specific Inhibition of Prion Infection by Swainsonine

We determined the susceptibility of a cell line to persistent infection by a prion strain by the SSCA (21, 23). In short, we exposed the cells to various dilutions of prion-infected mouse brain homogenate, propagated them for three splits, and measured the proportion of PrPSc positive cells by an ELISA-based procedure. We designated as Response Index (RI) a sample the reciprocal of the dilution that gives rise to a designated proportion of infected cells under standard assay conditions (usually 1.5% of the population).

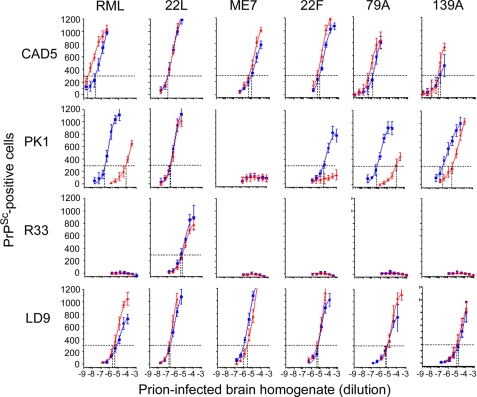

Because PrP glycosylation has been proposed to play a role in prion strain specificity (36), we examined the effect of glycosylation inhibitors on the propagation of several prion strains in PK1, R33, CAD5, and LD9 cells (22). We observed a surprising effect of swa, an inhibitor of Golgi α-mannosidase II. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1, it inhibited persistent infection of PK1 cells by RML, 79A and 22F about 99%, with an ED50 of about 1.7–5.2 ng/ml (10–30 nm) (supplemental Fig. S2), but it had no effect on infection by 22L and only moderately diminished infection by 139A prions. Moreover, it did not inhibit infection of CAD5, R33, or LD9 cells by any of the above-mentioned strains (Fig. 1). Infection of PK1 cells with 22L or of CAD5 cells by RML was not inhibited by swa concentrations as high as 40 μg/ml (supplemental Fig. S3). We also examined the effect of other inhibitors of N-glycosylation on the SSCA. Both kifunensine, an inhibitor of α-mannosidase I, and to a lesser extent castanospermine, an inhibitor of α-glucosidase, caused cell- and strain-specific inhibition with similar patterns, which differed, however, from that given by swa (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of swainsonine on the response of PK1, Cath.a-differentiated, LD9, and R33 cells to various prion strains. Five thousand CAD5, PK1, R33, or LD9 cells were infected in the presence (red) or absence (blue) of 2 μg/ml swa with serial dilutions of brain homogenate infected with the prions indicated for 4 days, split three times, and 20,000 cells were analyzed for PrPSc by the PK-ELISA. The vertical dotted lines indicate the dilution of brain homogenate resulting in 300 PrPSc-positive cells; the reciprocal thereof defines the RI. swa inhibited the infection of PK1 cells with RML and 79A by 2.3 logs, 22F by >1.5 logs, and 139A by 1 log and did not inhibit infection with 22L. There was no effect on infection of LD9 cells. There was a slight, but consistent, stimulation of CAD5 cell infection by RML. Each data point is the average of six measurements.

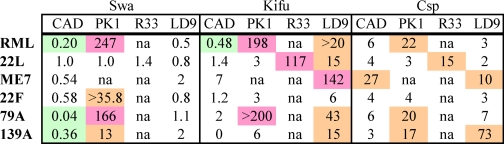

TABLE 1.

Effect of glycosylation inhibitors on infection of various cell lines with different prion strains

The ability of glycosylation inhibitors to block infection of cells in culture was assessed by the SSCA. The data are from Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S4. The RI is the reciprocal of the dilution of brain homogenate that yields 300 PrPSc-positive “spots.” The ability of a drug to inhibit prion infection is indicated by the ratio of the RIs in the absence or presence of drug. Combinations of cells, prion, and drug that are highlighted green moderately enhance susceptibility to infection. Orange and purple highlights indicate 1- and 2-log inhibitions of prion infection, respectively. The inhibition patterns of castanospermine (csp) and kifunensine (kifu) are similar and differ from that of swa. The RI values represent the average of six measurements. na, not applicable.

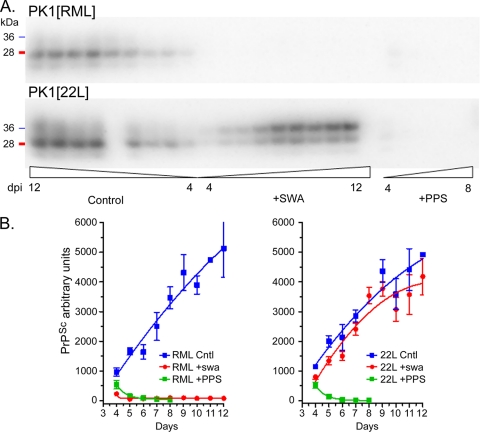

We assessed the accumulation of rPrPSc as a function of time after infection of PK1 cells with RML- or 22L-infected brain homogenate, in the absence or presence of swa. Fig. 2 shows that swa caused a complete inhibition of rPrPSc accumulation in RML-infected cells, but it had no effect on 22L-infected cells.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of swainsonine on accumulation of rPrPSc following infection with RML and 22L prions. Two 15-cm dishes containing 106 PK1 cells each were infected with RML or 22L PrP(27–30) (10−4 dilution, based on brain tissue = 1) in the presence or absence of swa (2 μg/ml) or pentosan polysulfate (PPS) (5 μg/ml) for 2 days. Infectious medium was replaced with medium with or without the drugs, and at 4 days post-infection (dpi), the cells were split 1:10 into 11 15-cm dishes containing the appropriate media. Cells were harvested from one dish for each condition daily, between 4 and 12 days post-infection, with an intervening 1:10 split at 8 days post-infection. Inocula were largely cleared by 5 days after infection, as monitored by infection in the presence of PPS, a potent inhibitor of rPrPSc synthesis (56). A, Western blots of PK-digested samples (40 μg of PK-digested protein/lane, equivalent to ∼150,000 cells) show abrogation of PrPSc accumulation in RML-infected but not in 22L-infected cells. The panels in B show the densitometric quantification. The 8-day 22L control sample was lost. Each time point represents the average from three Western blots. The experiment was carried out twice.

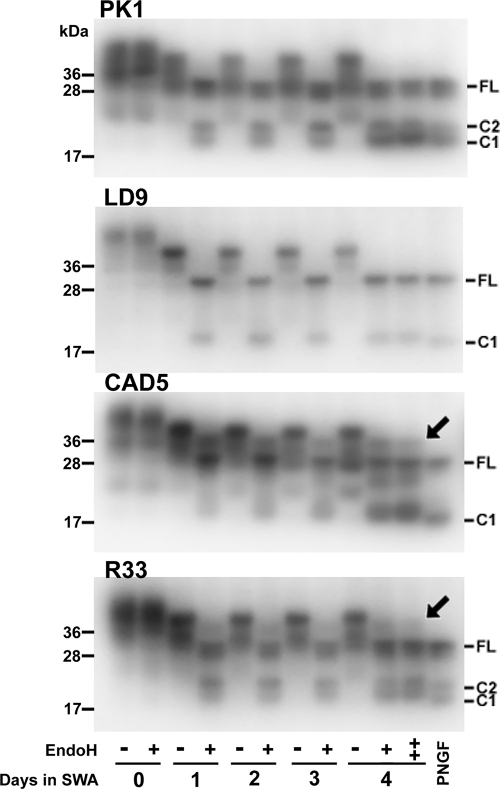

Because swa-induced prion inhibition appeared restricted to PK1 cells, we examined whether swa was equally efficient in preventing formation of complex glycans in cell lines other than PK1. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of 2 μg of swa/ml (11.6 μm) for 4 days, and lysates were digested with Endo-H and subjected to Western blot analysis. Endo-H cleaves high mannose but not complex glycans (37). As shown in Fig. 3, PrPC from all cell lines showed increased electrophoretic mobility after 1 day of exposure to swa, reflecting inhibition of complex glycosylation. PrPC from PK1 and LD9 cells became fully susceptible to Endo-H after 1 day; thus, the inability of swa to inhibit infection of LD9 cells by RML did not come about because it failed to inhibit complex glycosylation. CAD5 cells developed susceptibility to Endo-H cleavage more gradually, and neither CAD5 nor R33 cells became fully susceptible even after 4 days of exposure to swa. Flow cytometry of intact cells from the four lines, labeled with anti-PrP antibody D18, revealed that prolonged swa treatment did not reduce cell surface PrP (supplemental Fig. S5). swa did not affect the growth rate of any of the cell lines (supplemental Fig. S6). To confirm that inhibition of PK1 cell infection by swa, an octahydroindolizidine derivative, was indeed mediated by inhibition of α-mannosidase II, we investigated the effect of a structurally dissimilar inhibitor of the enzyme, mannostatin A (manA), a cyclopentitol derivative. Exposure of PK1 cells to manA rendered PrPC susceptible to Endo-H cleavage; however, even after 7 days at 20 μg of manA/ml deglycosylation was not as complete as with 2 μg of swa/ml (supplemental Fig. S7A). RML infection of PK1 cells was inhibited by 1.5 logs at 100 μg of manA/ml, as compared with 2.3 logs for 2 μg of swa/ml (supplemental Fig. S7B). The ED50 value for inhibition by manA was about 6 μg/ml (30 μm) (supplemental Fig. S7C), i.e. about 1000 times higher than for swa. In a further experiment, infection of PK1 cells by 22L was not inhibited by 20 μg of manA/ml (supplemental Fig. S7D), whereas infection by RML was inhibited by about 1 log. These experiments confirm that misglycosylation renders PK1 cells resistant to RML but not to 22L, although the efficiency of the inhibitors differed.

FIGURE 3.

Swainsonine treatment of PK1, LD9, CAD5, and R33 cells renders glycans susceptible to Endo-H cleavage. Cells were propagated in 2 μg of swa/ml for the times indicated, and cell lysates, digested or not with Endo-H or PNGaseF, were analyzed by Western blotting. Misglycosylation of PrP was evident after 1 day of swa treatment, as shown by increased electrophoretic mobility of the slowest PrPC band (diglycosylated PrPC) for all cell lines. The PrP-linked glycans of PK1 and LD9 became fully susceptible to Endo-H treatment after 1 day of swa treatment, but in the case of CAD5 and R33 cells some PrP remained Endo-H-resistant even after 4 days. “++” designates 4-day samples that were treated twice with Endo-H to ensure complete cleavage of all susceptible glycans. The arrows point to residual endo H-resistant PrPC. C2 is a fragment arising from cleavage between positions 110/111 of PrPC in uninfected cells (62). C1, due to cleavage around position 90, is usually predominant in prion-infected cells but has also been reported in uninfected cells (63). The data shown are from one of three experiments.

PrPSc Uptake by PK1 Cells Is Not Inhibited by swa

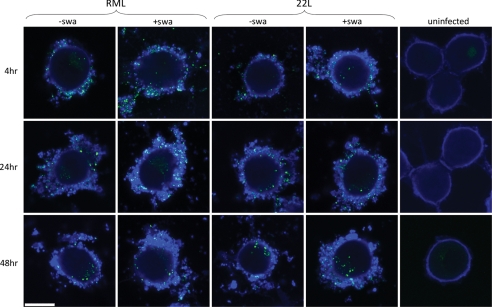

Magalhaes et al. (38) showed that purified, fluorescently labeled PrPSc is internalized by unspecific pinocytosis or transcytosis into late endosomes and/or lysosomes within hours of exposure; it first appears in cells in the form of discrete particles that are eventually finely dispersed. We propagated PK1 cells in the presence or absence of swa for 3 days. At 4, 24, or 48 h after infection with 10−3 RML- or 22L-infected brain homogenate, cells were treated with thermolysin, biotinylated with a nonpermeating biotinylation reagent to visualize the cell surface, fixed, and fluorescently stained for protease-resistant PrP and biotin, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, untreated cells were outlined by a thin layer of biotinylated material; addition of prion-infected brain homogenate resulted in a thick coating of biotinylated material, doubtlessly derived from the homogenate, with embedded granules of protease-resistant PrP (“PrPSc”). Only a surprisingly small proportion of PrPSc granules was internalized, to about the same extent in the presence or absence of swa, in both RML and 22L-infected cells (supplemental Table S1).

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of “rPrPSc granules” outside and inside cells at various times after infection with RML or 22L, in the absence or presence of swa. PK1 cells were grown for 3 days with or without 2 μg of swa/ml and exposed to a 10−3 dilution of RML or 22L brain homogenate for various times. At 4, 24, and 48 h post-infection, cells were digested with thermolysin to remove PrPC, biotinylated to visualize the cell surface, fixed, and fluorescently stained for rPrPSc (green) and biotin (blue). A thick layer of biotinylated material coated the surface of infected cells, as compared with a faint layer on uninfected cells. External and internal granules of rPrPSc were quantified by confocal imaging (supplemental Table S1). Relatively few rPrPSc granules were internalized, but uptake was not affected by swa. White bar, 10 μm.

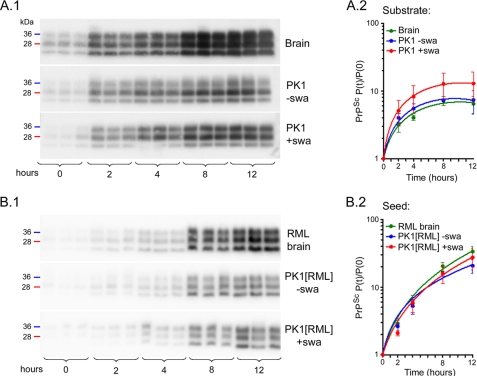

Misglycosylated PrPC Is a Competent Substrate and Misglycosylated PrPSc a Competent Seed for PrPSc Amplification by PMCA

The fact that propagation of RML prions was not impaired in swa-treated LD9 cells strongly indicated that misglycosylated PrPC could be readily converted to PrPSc. To assess whether this was also the case for misglycosylated PrPC from PK1 cells, we compared the amplification efficiency of normal and misglycosylated PrPC by PMCA. We used lysates of untreated and swa-treated PK1 cells as substrate and 6.25 × 10−4 diluted RML brain homogenate as seed; samples were subjected to cycles of 20 s of sonication and 30 min of incubation for the times indicated, and rPrPSc was determined. As shown in Fig. 5A, the rate of PrPSc formation was similar for normal and misglycosylated PrP substrate. In a further experiment, PMCA reactions carried out with normal mouse brain homogenate as substrate showed that, in vitro, normal and misglycosylated PrPSc were equally effective as seed (Fig. 5B). Thus, normal and misglycosylated PrPC were equally effective as substrate, and normal and misglycosylated PrPSc were equally competent as seed.

FIGURE 5.

Misglycosylated and normal PrPC are equally efficient substrates, and misglycosylated and normal PrPSc are equally efficient seeds for PMCA amplification. A, cell lysates from PK1 cells (4 × 107 cells/ml) propagated in the presence (red) or absence (blue) of 2 μg of swa/ml for 7 days, and 10% mouse brain homogenate as control (green), were seeded with RML-infected brain homogenate (6.25 × 10−4 final dilution), subjected to PMCA for the times indicated, and analyzed by Western blotting after PK digestion (A1). The blots were quantified, and the ratio rPrPSc(time 0)/rPrPSc(time t) was plotted on a log scale against time (A2). B, mouse brain homogenate (10%) was seeded with RML-infected brain homogenate (green) or lysate of PK1[RML] cells propagated with (red) or without (blue) 2 μg of swa/ml for 7 days. The cell-derived seed preparations were adjusted to the same PrPSc concentration as 6 × 10−5-diluted RML-infected brain homogenate. Samples were subjected to PMCA, processed, analyzed (B1), and plotted (B2) as above. The graphs show average and standard deviation from triplicate reactions. This experiment and two additional experiments (not shown) demonstrate the equivalence of misglycosylated and normal PrPC as substrates and of misglycosylated and normal PrPSc as seeds for PMCA amplification.

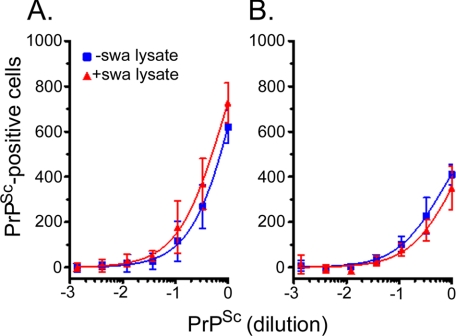

Misglycosylated and Normally Glycosylated PrPSc Are Equally Infectious to Cultured Cells

The inhibitory effect of swa on the propagation of RML could come about because misglycosylated RML PrPSc is a poor seed for the conversion reaction in vivo. To test this hypothesis, we propagated RML- and 22L-infected PK1 cells in the presence of 2 μg of swa/ml for 7 days, which rendered their PrPSc fully susceptible to digestion with Endo-H, or in the absence of the drug, and prepared lysates of the cells. PK1 cells were infected with serial dilutions of the lysates, which had been adjusted to contain the same level of PrPSc, and the infectivity was assessed by the SSCA. As recorded Fig. 6, lysates of PK1[RML] cells propagated in the presence or absence of swa, respectively, were equally infectious to PK1 cells; similar results were obtained with the PK1[22L] lysates that were used as controls. Thus, normally glycosylated and misglycosylated PrPSc were equally infectious to PK1 cells.

FIGURE 6.

Specific infectivity of prions from RML- or 22L-infected cells is not affected by propagation in swa. PK1 cells were infected with 10−3 diluted RML- or 22L-infected brain homogenate and propagated for five 1:10 splits, about 25 doublings, to yield PK1[RML]wp-P3 and PK1[22L]wp-P3. The populations were then grown for 7 days in the absence or presence of 2 μg of swa/ml. Cell lysates were adjusted to contain equal concentrations of rPrPSc, as determined by Western blotting. PK1 cells were infected with a serial dilution of lysates of PK1[RML]wp-P3 cells (A) or PK1[22L]wp-P3 cells (B), treated with swa (red) or untreated (blue) and subjected to the SSCA. The number of rPrPSc-positive cells per 20,000 cells is plotted against dilution of lysate. There was no difference in the infectivity of complex-glycosylated rPrPSc and swa-misglycosylated rPrPSc.

How Could the Inhibitory Effect of swa Come About?

Swa could cause reduction of PrPSc accumulation by reducing its synthesis rate, accelerating its clearance rate, increasing the growth rate of the cells, or by a combination of these factors.

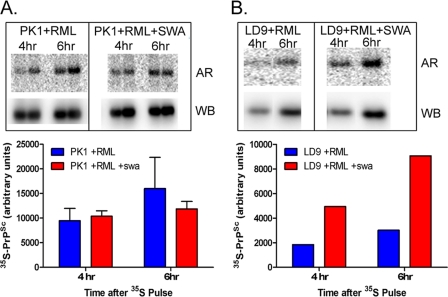

Swa had no effect on the growth rate of the cells (supplemental Fig. S6). We determined the rate of incorporation of 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine into PrPSc by PK1 cells 8 days after infection with RML, in the presence or absence of swa. After administering a 1-h pulse of the radioactive amino acids, samples were taken after 4 and 6 h, and PrPSc was purified, and its radioactivity was determined. As shown in Fig. 7A, the rates in the presence of swa were the same after 4 h and about 20% lower at 6 h after labeling; however, unpaired two-tail t tests revealed no significant difference between −swa and +swa samples at 4 (p = 0.682) or at 6 h (p = 0.464). In contrast to the results with PK1 cells, swa enhanced the rate of 35S label incorporation by RML-infected LD9 cells 2–3-fold (Fig. 7B). A 2–3-fold enhanced accumulation of PrPSc after 5 days of exposure of RML or 22L-infected LD9 cells to swa was confirmed in supplemental Fig. S8. These results do not allow a conclusion regarding the effect of swa on PrPSc synthesis in RML-infected PK1 cells, but they show that swa can have different effects on distinct cell lines.

FIGURE 7.

Incorporation of 35S-labeled amino acids into PrPSc in presence or absence of swa. On day 0, 106 PK1 cells (A) or LD9 cells (B) in 10-cm dishes were infected with 10−4 diluted RML-infected brain homogenate. On day 4, the medium was changed (PK1) or the cells split at 1:5 ratio (LD9) into medium with or without 2 μg/ml swa. On day 8, the cells were pulsed with 35S-labeled methionine and cysteine for 2 h, and the label was chased for 4 and 6 h. rPrPSc was purified by immunoprecipitation, and recovery of rPrPSc was assessed by Western blotting, and deglycosylated radioactive rPrPSc was assessed by autoradiography. The graphs show 35S-rPrPSc corrected for recovery. AR, autoradiogram, WB, Western blot. The experiment in A was performed in duplicate and that in B in singlicate.

Clearance of PrPSc can be caused by secretion, degradation, or a combination of both. Secretion of prions and PrPSc in association with exosomes has been described for N2a, GT-1, and RK13 cells (39–43). As shown in supplemental Table S2, the amount of PrPSc secreted by RML-infected PK1 cells within 12 h, in the absence and presence of swa was about 4 and 9%, respectively, of the cellular content. Because clearance of PrPSc from RML-infected N2a cells by imatinib was shown to be due to induction of autophagy (44), we determined the level of the autophagy marker LC3-II (45) in RML- and 22L-infected PK1 cells. The supplemental Fig. S9 shows that there was no significant increase in LC3-II expression when the cells were exposed to swa for 1–3 days, as compared with the strong increase after treatment with trehalose, a known inducer of autophagy (44), or with bafilomycin, which impairs LC3-II degradation (46–48). Proteasomal activity, as assayed by the Proteasome-GloTM cell-based assay (Promega) (49), was not increased in PK1 cells, uninfected or chronically infected with RML or 22L, after exposure to 2 μg of swa/ml for 4 days (data not shown). However, increased flux through the proteasomal or the lysosomal pathway was not excluded. In summary, no parameters associated with clearance were found to be significantly increased. However, as detailed under “Discussion,” even a 25% swa-induced increase of clearance would give rise to an almost 98% reduction of the PrPSc level during the 13-day period of the SSCA.

Subclones of PK1 Cells Show Varying Degrees of Susceptibility to Swainsonine Inhibition

Subclones of a cell population may vary widely in their properties, in particular in their susceptibility to infection by prion strains (22). We investigated whether the extent of swa inhibition of RML infection varied among PK1-derived subclones. We generated several subclones of the PK1-derived CAB19 (22), a clone in which, remarkably, swa inhibition of RML infection was more than 10-fold lower than in the parental PK1 cells. As shown in Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S10A, the RI−swa/RI+swa ratios on the CAB19 subclones ranged about 100-fold, from >400 for CAB19-2E4 to about 5 for CAB19-2D1, whereas the RIs for RML in the absence of swa ranged only about 7-fold.

TABLE 2.

Characterization of PK1 and selected PK1 subclones

Determination of RIs are shown in supplemental Fig. S10A. The clones were ranked by PrPC content; the RI−swa/RI+swa values, but not the RI−swa values, approximately followed this ranking. CAB19 is a subclone of PK1; CAB19-2D1, 2D12, 2E4, and 1H10 are subclones of CAB19.

| Exp. 1 |

Exp. 2 |

Doubling timea | PrPC |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI × 10−5 |

RI−swa/R1+swa | RI × 10−5 |

RI−swa/R1+swa | Westernb | Flow cytometryc | ||||

| -swa | +swa | -swa | +swa | ||||||

| h | |||||||||

| PK1 | 3.1 | 0.011 | 280 | 2 | 0.01 | 200 | 19.2 | ++++ | 100 |

| CAB19-2E4 | 5.6 | <0.01 | >560 | 9 | 0.03 | 270 | 24.3 | +++ | 35 |

| Cab19-1H10 | 21 | 1.1 | 19 | >2.5 | 0.82 | nd | 19.4 | ++++ | 35 |

| Cab19 | 12.2 | 1 | 12 | 11.4 | 0.86 | 13 | 20 | + | 27 |

| Cab19-2D12 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 11.1 | 0.55 | 20 | 24.7 | (+) | 20 |

| Cab19-2D1 | 3.1 | 0.83 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 0.53 | 6.1 | 21 | (+) | 21 |

a Growth rates were determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

b The Western blot is shown in supplemental Fig. S10C.

c Flow cytometry was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures”; PK1 value is set at 100%.

We quantified total PrPC levels by immunoblotting as well as cell surface PrPC by flow cytometry; Table 2 show that the cell lines with the lowest PrP expression levels, CAB19-2D12 and CAB19-2D1, exhibited the lowest swa-mediated inhibition, although their RIs for RML infection were higher than that of PK1 cells. To determine whether there was a causal link between PrP expression levels and swa-mediated inhibition, we reduced PrP expression of PK1 cells stepwise by transfection with increasing doses of PrP-specific siRNA, prior to infection with RML in the presence or absence of swa. As expected, the RI for RML was strongly dependent on the PrPC level, dropping from 3 × 106 to 104 as the PrPC level was reduced from control level (100%) to about 3%. In parallel, inhibition by swa also decreased, with the RIPK1/RIPK1+swa ratio dropping from 240 to 10 (Fig. 8). This finding can be explained if the swa effect is mediated by a cellular response to misglycosylated PrPSc; decreased expression of PrPC would result in lower levels of misglycosylated PrPSc and less enhancement of the clearance mechanism. However, as demonstrated by CAB19-1H10, high PrP expression was not sufficient to cause strong swa inhibition, showing that factors other than the PrPC or PrPSc levels play a role in mediating swa sensitivity, perhaps the cell's ability to respond to misglycosylated PrPSc.

FIGURE 8.

Response index of PK1 cells to RML and inhibition by swa are a function of PrPC expression level. PK1 cells were transfected with a serial dilution of PrP siRNA to attenuate PrPC expression. After 2 days, aliquots of the transfected cells were subjected to Western blot analysis for PrPC quantitation and to the SSCA using RML brain homogenate in the presence or absence of 2 μg of swa/ml. A, Western blot showing PrPC expression of PK1 cells treated with siRNA at the levels indicated. Unt, untreated cells. B, quantification of A. PrPC expression was reduced to ∼3% of untreated controls. C, RI of PK1 cells infected in the presence or absence of swa, as a function of PrPC expression at the time of infection. D, RI−swa/RI+swa decreased with decreasing levels of PrPC expression. Lipo, Lipofectamine only. The experiment was performed twice; each data point is from four samples.

swa did not inhibit RML infection of LD9 cells, although misglycosylation was as complete as in PK1 cells (Fig. 3). Because LD9 cells express PrPC at a lower level than PK1 cells, we transfected LD9 cells with a PrP expression plasmid and isolated clones expressing PrPC at about twice the level of the parent clone (supplemental Fig. S11), a level only slightly below that of PK1 cells and about equal to that of CAB19-2E4 (supplemental Fig. S10B). Nonetheless, the overexpressing LD9 clones did not show swa-mediated inhibition of infection, in contrast to CAB19-2E4 cells, which showed an RI−swa/RI+swa ratio of >559 (Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S10A).

In summary, not only is inhibition of RML prion replication by swa restricted to PK1 cells (among the lines examined), but even sublines of PK1 show a highly variable response to the inhibitor, which in most instances is correlated with their PrPC level.

DISCUSSION

Drugs inhibiting prion propagation in cell culture are directed at a variety of targets, which only occasionally are well defined. Anti-PrP antibodies sequester cell surface PrPC and/or prevent its conversion into PrPSc, eventually leading to complete clearance of infectivity (50–52). Compounds such as [meso-tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridinio)porphyrinato]iron(III) (53) stabilize PrPC, interfering with its conversion to PrPSc (54). Efficient clearance of prion infection can be achieved by imatinib, a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that elicits autophagy and thereby accelerates degradation of PrPSc (55). Highly conjugated amyloidophilic compounds such as Congo Red or curcumin, which may cure prion-infected cells at high nanomolar levels (56–58), bind not only to amyloid but also unspecifically to nonamyloid proteins (59), and the effective target or targets remain unknown. Kocisko et al. (60) have published a list of 40 compounds, whose IC50 values for inhibiting PrPSc formation in N2a cells range from 100 nm to “<1 μm” for RML and to “1–10 μm” for 22L, in addition to curcumin, whose IC50 value for RML was 10 nm and for 22L >10 μm.

Swainsonine aroused our interest because on the one hand it has a precise biochemical target, namely Golgi α-mannosidase II, whose inhibition results in misglycosylation of cellular proteins, and on the other hand it prevents chronic infection of PK1 cells with RML with an IC50 of about 20 nm, while not affecting infection with 22L prions even at 200 μm. Moreover, swa failed to inhibit infection of CAD5 or LD9 cells by RML, 22L, or ME7 prions. We found that RML PrPSc internalization was not diminished by swa and that misglycosylated PrPC and PrPSc were not impaired as substrate or seed, respectively, in the PMCA reaction.

As determined by the SSCA, swa reduced the number of infected cells resulting from the exposure of PK1 cells to RML by 1.5 to 2 logs. The SSCA reflects PrPSc accumulation over 13 days, assuming that a cell is infected by a single prion with a doubling time of 0.6 days (i.e. somewhat lower than the doubling time of the host cells, about 0.8 days), then even if swa reduced the rate of accumulation by as little as 25%, the overall inhibition of accumulation would be 97.7% (see supplemental “Discussion” for calculations).

Reduction of chronic infection by swa could come about by reduction of prion uptake, by inhibition of prion synthesis, augmentation of prion clearance, or acceleration of host cell division in the absence of accelerated prion replication. We found neither reduction of PrPSc uptake nor acceleration of host cell division. Direct measurement of PrPSc synthesis indicated some rate reduction as determined after a 6-h pulse; however, the measurements were not statistically significant. The finding that the swa effect decreased with decreasing PrPC expression level in a set of PK1 subclones or in PK1 cells exposed to increasing levels of PrP-specific siRNA is more readily explained by an effect on synthesis than on clearance. However, although there was no indication of swa affecting autophagy, an effect on clearance of PrPSc has not been excluded. It is interesting that in CAD5 cells susceptibility to infection by RML, and to a lesser degree by other strains, was enhanced by swa (Fig. 1) and that exposure to swa of chronically RML-infected LD9 cells (supplemental Fig. S8) or ScN2a cells (61) resulted in an increase in PrPSc levels. The finding that the swa effect varies greatly in different host cells argues that it is mediated by the misglycosylation of host proteins other than PrP. In view of the very different susceptibilities of cell lines to infection by diverse prion strains, host proteins must play a critical role both in prion synthesis, perhaps as chaperones, and in clearance, where they may mediate transport to the degradative compartment and degradation. Misglycosylation of such host proteins could lead either to an enhancement or decrease in prion levels, depending on which pathway is preferentially affected.

Even though the mechanism by which swa and other glycosylation inhibitors exert their effects remains unclear, their use has significantly enhanced the discriminatory power of the cell panel assay. Thus, it became possible to discriminate between 139A and 79A prions on PK1 cells in the presence, or absence of swa or on LD9 cells in the presence or absence of castanospermine, and between 22F and 79A on PK1 cells in the presence or absence of kifunensine (Table 1). Acquisition of swa sensitivity by 22L prions transferred from brain to PK1 cells (28) or from R33 to PK1 cells (29) was essential for the demonstration of prion adaptation to the environment. In addition, the discovery that swa-sensitive prions can acquire swa resistance when propagated in the presence of the drug enabled the demonstration that pathogens devoid of nucleic acid can undergo Darwinian evolution in cell culture (28).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Frank Dorsey and John Cleveland (Scripps Florida) for the generous gift of anti-LC3 antibody, Anja Oelschlegel for assaying chymotrypsin-like protease, Corinne Lasmezas for valuable discussions, and Alexandra Sherman for supplying prion-infected brains.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 1RO1NSO59543 and 1RO1NS067214. This work was also supported by The Alafi Family Foundation (to C. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2, Figs. S1–S11, “Results,” and “Discussion”.

S. Browning, C. A. Baker, E. Smith, S. P. Mahal, M. E. Herva, C. A. Demczyk, J. Li, and C. Weissmann, unpublished observations.

- PrP

- prion protein

- BGS

- bovine growth serum

- manA

- mannostatin A

- PMCA

- protein misfolding cyclic amplification

- RI

- response index

- SSCA

- standard scrapie cell assay

- swa

- swainsonine

- bis-tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- PNGase

- peptide:N-glycosidase

- Endo-H

- endoglycosidase H.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jarrett J. T., Lansbury P. T., Jr. (1993) Cell 73, 1055–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gajdusek D. C. (1988) J. Neuroimmunol. 20, 95–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Endo T., Groth D., Prusiner S. B., Kobata A. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8380–8388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rudd P. M., Wormald M. R., Wing D. R., Prusiner S. B., Dwek R. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 3759–3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Safar J., Wille H., Itri V., Groth D., Serban H., Torchia M., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (1998) Nat. Med. 4, 1157–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tzaban S., Friedlander G., Schonberger O., Horonchik L., Yedidia Y., Shaked G., Gabizon R., Taraboulos A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 12868–12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thackray A. M., Hopkins L., Bujdoso R. (2007) Biochem. J. 401, 475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nazor K. E., Kuhn F., Seward T., Green M., Zwald D., Pürro M., Schmid J., Biffiger K., Power A. M., Oesch B., Raeber A. J., Telling G. C. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 2472–2480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gambetti P., Dong Z., Yuan J., Xiao X., Zheng M., Alshekhlee A., Castellani R., Cohen M., Barria M. A., Gonzalez-Romero D., Belay E. D., Schonberger L. B., Marder K., Harris C., Burke J. R., Montine T., Wisniewski T., Dickson D. W., Soto C., Hulette C. M., Mastrianni J. A., Kong Q., Zou W. Q. (2008) Ann. Neurol. 63, 697–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D'Castro L., Wenborn A., Gros N., Joiner S., Cronier S., Collinge J., Wadsworth J. D. (2010) PLoS ONE 5, e15679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bruce M. E., Fraser H., McBride P. A., Scott J. R., Dickinson A. G. (1992) in Prion Diseases of Humans and Animals (Prusiner S. B., Collinge J., Powell J., Anderton B. eds) pp. 497–508, Ellis Horwood, New York [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bessen R. A., Marsh R. F. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 2096–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Telling G. C., Parchi P., DeArmond S. J., Cortelli P., Montagna P., Gabizon R., Mastrianni J., Lugaresi E., Gambetti P., Prusiner S. B. (1996) Science 274, 2079–2082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peretz D., Scott M. R., Groth D., Williamson R. A., Burton D. R., Cohen F. E., Prusiner S. B. (2001) Protein Sci. 10, 854–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collinge J., Clarke A. R. (2007) Science 318, 930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weissmann C. (2009) Folia Neuropathol. 47, 104–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanaka M., Collins S. R., Toyama B. H., Weissman J. S. (2006) Nature 442, 585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Race R. E., Fadness L. H., Chesebro B. (1987) J. Gen. Virol. 68, 1391–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Butler D. A., Scott M. R., Bockman J. M., Borchelt D. R., Taraboulos A., Hsiao K. K., Kingsbury D. T., Prusiner S. B. (1988) J. Virol. 62, 1558–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lehmann S. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 299, 227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klöhn P. C., Stoltze L., Flechsig E., Enari M., Weissmann C. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 11666–11671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahal S. P., Baker C. A., Demczyk C. A., Smith E. W., Julius C., Weissmann C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20908–20913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahal S. P., Demczyk C. A., Smith E. W., Klöhn P. C., Weissmann C. (2008) in Methods in Molecular Biology: Prions (Hill A. F. ed) Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Groschup M. H., Gretzschel A., Kuczius T. (2006) in Prions in Humans and Animals (Hornlimann B., Riesner D., Kretschmar H. eds) pp. 166–183, De Gruyter, New York [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tulsiani D. R., Harris T. M., Touster O. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 7936–7939 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tulsiani D. R., Touster O. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 7578–7585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Crispin M., Aricescu A. R., Chang V. T., Jones E. Y., Stuart D. I., Dwek R. A., Davis S. J., Harvey D. J. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581, 1963–1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li J., Browning S., Mahal S. P., Oelschlegel A. M., Weissmann C. (2010) Science 327, 869–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahal S. P., Browning S., Li J., Suponitsky-Kroyter I., Weissmann C. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 22653–22658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Williamson R. A., Peretz D., Pinilla C., Ball H., Bastidas R. B., Rozenshteyn R., Houghten R. A., Prusiner S. B., Burton D. R. (1998) J. Virol. 72, 9413–9418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saá P., Castilla J., Soto C. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 299, 53–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mays C. E., Yeom J., Kang H. E., Bian J., Khaychuk V., Kim Y., Bartz J. C., Telling G. C., Ryou C. (2011) PLoS ONE 6, e18047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marijanovic Z., Caputo A., Campana V., Zurzolo C. (2009) PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cronier S., Gros N., Tattum M. H., Jackson G. S., Clarke A. R., Collinge J., Wadsworth J. D. (2008) Biochem. J. 416, 297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wadsworth J. D., Joiner S., Hill A. F., Campbell T. A., Desbruslais M., Luthert P. J., Collinge J. (2001) Lancet 358, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeArmond S. J., Qiu Y., Sànchez H., Spilman P. R., Ninchak-Casey A., Alonso D., Daggett V. (1999) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 1000–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tarentino A. L., Plummer T. H., Jr. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 230, 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Magalhães A. C., Baron G. S., Lee K. S., Steele-Mortimer O., Dorward D., Prado M. A., Caughey B. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 5207–5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alais S., Simoes S., Baas D., Lehmann S., Raposo G., Darlix J. L., Leblanc P. (2008) Biol. Cell 100, 603–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Veith N. M., Plattner H., Stuermer C. A., Schulz-Schaeffer W. J., Bürkle A. (2009) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 88, 45–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leblanc P., Alais S., Porto-Carreiro I., Lehmann S., Grassi J., Raposo G., Darlix J. L. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2674–2685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vella L. J., Sharples R. A., Lawson V. A., Masters C. L., Cappai R., Hill A. F. (2007) J. Pathol. 211, 582–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fevrier B., Vilette D., Archer F., Loew D., Faigle W., Vidal M., Laude H., Raposo G. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9683–9688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aguib Y., Heiseke A., Gilch S., Riemer C., Baier M., Schätzl H. M., Ertmer A. (2009) Autophagy 5, 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kabeya Y., Mizushima N., Ueno T., Yamamoto A., Kirisako T., Noda T., Kominami E., Ohsumi Y., Yoshimori T. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 5720–5728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klionsky D. J., Elazar Z., Seglen P. O., Rubinsztein D. C. (2008) Autophagy 4, 849–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yamamoto A., Tagawa Y., Yoshimori T., Moriyama Y., Masaki R., Tashiro Y. (1998) Cell Struct. Funct. 23, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rubinsztein D. C., Cuervo A. M., Ravikumar B., Sarkar S., Korolchuk V., Kaushik S., Klionsky D. J. (2009) Autophagy 5, 585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Moravec R. A., O'Brien M. A., Daily W. J., Scurria M. A., Bernad L., Riss T. L. (2009) Anal. Biochem. 387, 294–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Enari M., Flechsig E., Weissmann C. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9295–9299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Peretz D., Williamson R. A., Kaneko K., Vergara J., Leclerc E., Schmitt-Ulms G., Mehlhorn I. R., Legname G., Wormald M. R., Rudd P. M., Dwek R. A., Burton D. R., Prusiner S. B. (2001) Nature 412, 739–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Perrier V., Solassol J., Crozet C., Frobert Y., Mourton-Gilles C., Grassi J., Lehmann S. (2004) J. Neurochem. 89, 454–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caughey W. S., Raymond L. D., Horiuchi M., Caughey B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12117–12122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nicoll A. J., Trevitt C. R., Tattum M. H., Risse E., Quarterman E., Ibarra A. A., Wright C., Jackson G. S., Sessions R. B., Farrow M., Waltho J. P., Clarke A. R., Collinge J. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17610–17615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heiseke A., Aguib Y., Schatzl H. M. (2010) Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 12, 87–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Caughey B., Raymond G. J. (1993) J. Virol. 67, 643–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Demaimay R., Harper J., Gordon H., Weaver D., Chesebro B., Caughey B. (1998) J. Neurochem. 71, 2534–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Caughey B., Raymond L. D., Raymond G. J., Maxson L., Silveira J., Baron G. S. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 5499–5502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feng B. Y., Toyama B. H., Wille H., Colby D. W., Collins S. R., May B. C., Prusiner S. B., Weissman J., Shoichet B. K. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 197–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kocisko D. A., Engel A. L., Harbuck K., Arnold K. M., Olsen E. A., Raymond L. D., Vilette D., Caughey B. (2005) Neurosci. Lett. 388, 106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Winklhofer K. F., Heller U., Reintjes A., Tatzelt J. (2003) Traffic 4, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vincent B., Paitel E., Frobert Y., Lehmann S., Grassi J., Checler F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35612–35616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yadavalli R., Guttmann R. P., Seward T., Centers A. P., Williamson R. A., Telling G. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21948–21956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.