Background: Modification of the MART-127–35 tumor antigen to improve MHC binding severely curtails immunogenicity with minimal structural alterations.

Results: Modification enhances the flexibility of the peptide and MHC.

Conclusion: Dynamical consequences of peptide modification contribute to the loss in antigenicity.

Significance: Potential dynamical consequences should be considered in the design of peptide-based vaccines and may underlie aspects of T cell specificity.

Keywords: Antigen Presentation, Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), Protein Dynamics, Thermodynamics, Vaccine Development

Abstract

Modification of the primary anchor positions of antigenic peptides to improve binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins is a commonly used strategy for engineering peptide-based vaccine candidates. However, such peptide modifications do not always improve antigenicity, complicating efforts to design effective vaccines for cancer and infectious disease. Here we investigated the MART-127–35 tumor antigen, for which anchor modification (replacement of the position two alanine with leucine) dramatically reduces or ablates antigenicity with a wide range of T cell clones despite significantly improving peptide binding to MHC. We found that anchor modification in the MART-127–35 antigen enhances the flexibility of both the peptide and the HLA-A*0201 molecule. Although the resulting entropic effects contribute to the improved binding of the peptide to MHC, they also negatively impact T cell receptor binding to the peptide·MHC complex. These results help explain how the “anchor-fixing” strategy fails to improve antigenicity in this case, and more generally, may be relevant for understanding the high specificity characteristic of the T cell repertoire. In addition to impacting vaccine design, modulation of peptide and MHC flexibility through changes to antigenic peptides may present an evolutionary strategy for the escape of pathogens from immune destruction.

Introduction

T cell receptor (TCR)5 recognition of an antigenic peptide bound and presented by a class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) protein underlies the cytotoxic immune response to pathogens and cancer. Many tumor or viral antigens are poorly immunogenic, which can sometimes be attributed to weak binding of the peptide to the MHC molecule, consequently resulting in low antigen density on the surface of a presenting cell (1). One approach for vaccine design involves improving peptide-MHC affinity, with the goal of using the modified peptides to convert naive antigen-specific T cells into more sensitive effector T cells. This strategy is often employed when weak peptide binding results from the presence of suboptimal “anchor” residues within the peptide sequence (2, 3). Many clinical trials employing anchor-modified peptides have been performed or are in progress.

However, improving peptide binding by substituting suboptimal with optimal anchor residues does not always enhance antigenicity, complicating efforts to engineer peptide-based vaccines. A clear example of this is seen with the MART-127–35 melanoma antigen (sequence AAGIGILTV; referred to here as AAG),6 which possesses an alanine at position 2 and binds weakly to the restricting class I MHC molecule, HLA-A*0201 (HLA-A2). Valmori et al. (2) found that when the second alanine of the AAG peptide was replaced with leucine, generating the peptide ALGIGILTV (referred to here as ALG), peptide binding to HLA-A2 was enhanced 40-fold, but antigenicity was severely curtailed. This result has been confirmed with multiple T cell clones (4, 5) as well as staining experiments with pMHC tetramers (5). Interestingly, however, T cells that recognize the ALG peptide poorly (or not at all) readily cross-react with a decameric form of the native MART-1 peptide possessing a glutamic acid at the N terminus (EAAGIGILTV; referred to as EAA) (2, 4, 5). Previously, these results were interpreted to indicate that anchor modification of the nonameric peptide altered the conformation away from one shared by the native nonamer and the decamer (6, 7).

However, when the structures of the native and anchor-modified nonamers bound to HLA-A2 were determined, it was observed that the alanine-to-leucine modification at position 2 had only a minor effect on the conformation of the peptide (4). Indeed, the structural differences between the AAG and ALG nonamers were substantially less than the differences between the AAG nonamer and the EAA decamer, leading us to question how multiple T cell clones could on one hand be highly sensitive to a very small structural perturbation while on the other tolerant of a much more dramatic structural difference. This question reflects the well appreciated yet poorly understood dichotomy of high specificity together with high cross-reactivity that is characteristic of the T cell arm of the immune system.

Here we investigated the consequences of anchor modification of the MART-127–35 AAG peptide, aiming to understand how the “anchor-fixing” strategy fails despite achieving the goal of enhancing peptide binding affinity with only minor conformational consequences. We found that the alanine-to-leucine substitution at position 2 increases the flexibility of the N-terminal half of the MART-1 peptide, leading to the subtle structural effects seen crystallographically. Anchor modification also increases the flexibility of the helices that form the peptide binding domain. The increased flexibility and thus higher entropy of the complex with the modified ALG peptide contributes to the improvement in peptide binding to HLA-A2. However, it will also raise the entropic cost for TCR binding to the pMHC complex, contributing to a general loss in affinity with MART-1-specific TCRs. These results have implications not only for vaccine design and other efforts to alter immunogenicity through peptide modification but also for our understanding of the mechanisms of viral and tumor escape from immune destruction and the origins of T cell receptor specificity in general.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Proteins and Peptides

Recombinant T cell receptor and complexes between peptides and HLA-A2 were produced by refolding from bacterially expressed inclusion bodies (HLA-A2 heavy chain and β2-microglobulin for MHC and α and β chains for TCR) and chromatographically purified as described previously (8). Purified peptides were obtained commercially (GenScript) and verified through mass spectrometry. The construct for the DMF5 TCR utilized an engineered disulfide bond across the α and β constant domains for improved stability (9).

Circular Dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements were performed in an Aviv 62DS instrument as described previously (10), monitoring a wavelength of 218 nm and using a temperature increment of 0.3 °C/min. Solution conditions were 20 mm sodium phosphate, 75 mm sodium chloride, pH 7.4, and a protein concentration of 10 μm. As unfolding of peptide·HLA-A2 complexes is irreversible, the data were fit to a six-order polynomial, and the apparent Tm was taken from the first derivative of the fitted curve.

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Steady-state surface plasmon resonance experiments were performed with a Biacore 3000 instrument as described previously (8), except that for measurements with the AAG and ALG peptides, the activity of the sensor surface was fixed with the value determined with the EAA decamer (11). DMF5 TCR was coupled to the sensor surface using amine coupling. Peptide·HLA-A2 complexes were injected in duplicate, utilizing a flow rate of 5 μl/min. Solution conditions were 20 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 0.005% Nonidet P-20, pH 7.4, 25 °C.

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals of the AAG·HLA-A2 complex were grown at 4 °C from 24% PEG 3350, 25 mm MES, 0.1 m NaCl, pH 6.5, using sitting drop/vapor diffusion. Cryo-protection involved soaking crystals in crystallization solution supplemented with 20% glycerol for several seconds before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at beamline 19BM of the Structural Biology Center at the Argonne National Laboratory and processed with HKL2000 (12). Structures were solved with MOLREP (13) using the gp100209·HLA-A2 structure (14) as a search model with coordinates for peptide and solvent removed. Structures were refined with Refmac5 (15) and verified as described previously (4), except that Molprobity (16) was used as an additional validation tool.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Spectra for AAG and ALG bound to HLA-A2 were recorded at 277 K on a Bruker Avance 800-MHz magnet fitted with a cryogenic probe. The NMR sample contained ∼250 μm pMHC in a volume of 300 μl using a Shigemi NMR tube. To enhance probe sensitivity, a low conductivity buffer (20 mm 2d-BIS-TRIS buffer with 2d-benzoic acid, pH 7.4) was used (17). Temperature calibration on the cryogenic probe was performed using ethylene glycol. 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectra were obtained using a transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy version of the pulse sequence (18, 19). Spectra were processed using TOPSPIN 1.3 (Bruker Biospin) and plotted using Sparky 3.113 (41).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed with the AMBER 8 suite (20). For the 300 K simulations, we continued the simulations described in Ref. 4 from their endpoints, utilizing the previously described protocol. Briefly, starting coordinates for the AAG simulation were from the coordinates in the first molecule in the asymmetric unit of the previously solved structure (4). Starting coordinates for the ALG simulation were from Sliz et al. (6). Hydrogen atoms were added, and the proteins were immersed in TIP3P water boxes along with sodium cations for neutrality. Equilibration consisted of multiple steps of energy minimization followed by short molecular dynamics runs in which restraints were gradually removed. Production runs utilized a 2-fs time step with the SHAKE algorithm. Simulations at 330 K used the same protocol and the same prepared systems, with equilibration and production simulations performed at a temperature of 330 rather than 300 K. Trajectory analysis was performed with the AMBER ptraj tool and in-house scripts.

Peptide Dissociation Kinetics

Peptide dissociation from HLA-A2 was monitored using fluorescence anisotropy as described previously (21, 22), utilizing a temperature-controlled Beacon 2000 instrument to monitor steady-state anisotropy (Invitrogen). Solution conditions were 10 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4. AAG and ALG peptides were labeled with fluorescein by replacing leucine at position 7 with a fluorescein-derivatized lysine. Data were fit to either single or biphasic exponential decays using OriginPro 7.5 (OriginLab), with the dominant slow process for the biphasic decays interpreted as resulting from peptide dissociation from the HLA-A2 heavy chain as described in Ref. 21.

RESULTS

The ALG·HLA-A2 Complex Is Poorly Recognized by MART-127–35-specific TCRs in a Direct Binding Experiment

Despite its improved binding to HLA-A2, the anchor-modified variant of the MART-127–35 nonamer (ALG) is recognized very poorly, and in some cases not at all, in functional assays with T cells that recognize the native peptide (AAG). Although this result has been replicated with a number of T cell clones and lines and also seen with MHC-tetramer binding experiments (2, 4, 5), it remains possible that these outcomes are attributable to issues not related to TCR binding, such as preferential proteolysis of the ALG peptide in cellular assays. For this reason, we examined peptide binding to HLA-A2 and TCR binding to peptide·HLA-A2 complexes in direct assays with recombinant protein.

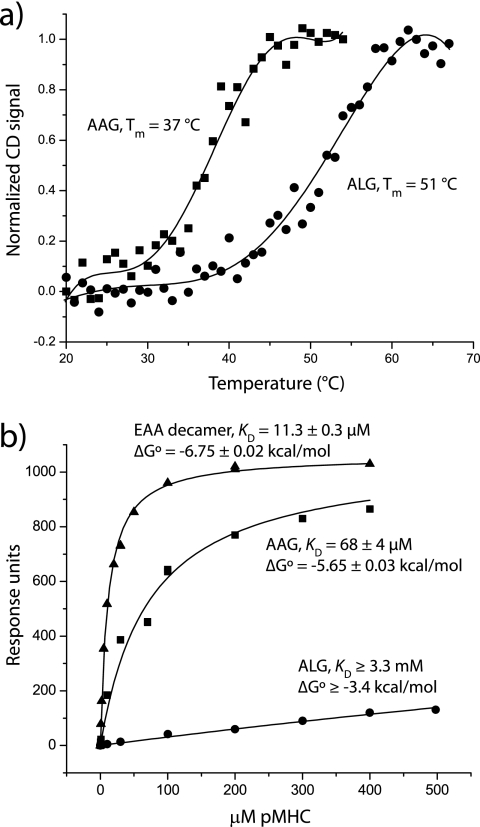

First, to confirm the improved binding of the ALG peptide to HLA-A2, we examined the thermal stability of purified peptide·HLA-A2 complexes. Using circular dichroism to monitor HLA-A2 unfolding, we found that the ALG·HLA-A2 complex was substantially more stable than the AAG·HLA-A2 complex (Fig. 1a); the Tm of the AAG·HLA-A2 complex was 37 °C, whereas the Tm of the ALG·HLA-A2 complex was substantially higher at 51 °C. This large shift of 14 °C is consistent with the 40-fold increase in peptide binding affinity measured previously in competition assays (2).

FIGURE 1.

Anchor modification of the MART-127–35 peptide strengthens peptide binding to MHC but weakens TCR binding to pMHC. a, thermal stability monitored by circular dichroism indicates that the apparent Tm of the ALG·HLA-A2 complex is 14° higher than that of the AAG·HLA-A2 complex, consistent with the reported 40-fold increase in peptide binding affinity (2). b, although it recognizes the AAG·HLA-A2 and EAA·HLA-A2 complexes with moderate affinities, the DMF5 TCR binds the ALG·HLA-A2 complex very weakly, consistent with the loss in antigenicity seen with the ALG peptide.

We next examined TCR binding to peptide·HLA-A2 complexes in a direct binding assay using surface plasmon resonance with a recombinant MART-1-specific TCR. As shown in Fig. 1b, in an experiment optimized to detect weak binding (11), the DMF5 TCR (23) showed very weak binding with the ALG peptide despite stronger binding with both the AAG nonamer and the EAA decamer. In terms of binding free energy, the loss with the ALG peptide relative to the AAG peptide is at least 2.3 kcal/mol. These data track the functional results with T cells expressing DMF5, which of all the various MART-1 peptides recognizes the ALG nonamer the weakest (4).

Structures of the AAG and ALG Nonamer·HLA-A2 Complexes Indicate Greater Conformational Diversity for the ALG Versus the AAG Nonamer

The previously solved crystallographic structures of HLA-A2 bound to the AAG and ALG peptides showed that peptide modification did little to alter the conformation of the peptide or the MHC binding groove. Rather, modification had a subtle effect, introducing a small degree of structural heterogeneity into the center of the peptide (4). Both the AAG·HLA-A2 and the ALG·HLA-A2 structures had two pMHC molecules per asymmetric unit. In the structure with the native AAG nonamer, the backbones of the two peptides diverged in the center by only 0.5 Å (measured at the Cα of Gly-5). In the structure with the modified ALG nonamer, the divergence at the Gly-5 Cα was larger at 1.5 Å. More dramatically, however, in the ALG·HLA-A2 structure, the center of the peptide in the first molecule in the asymmetric unit occupied two conformations, differing by 180° “flips” of the ψ angle of Ile-4 and the φ angle of Gly-5. The peptide backbone in the AAG·HLA-A2 structure, on the other hand, adopted only a single conformation, corresponding to the “non-flipped” conformation in the ALG·HLA-A2 structure.

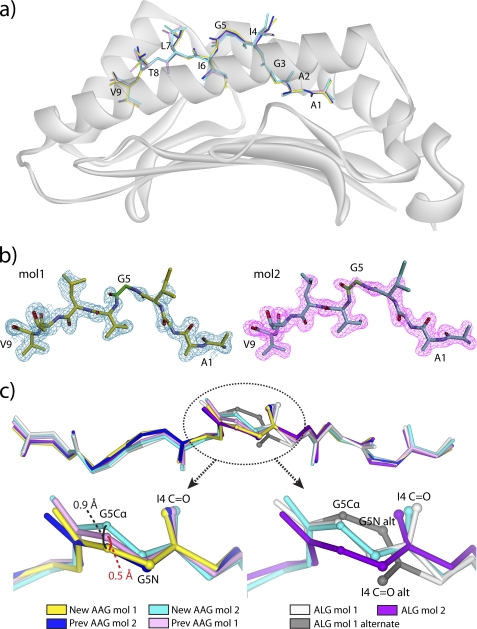

A complication of those data, however, was that the AAG·HLA-A2 and ALG·HLA-A2 complexes crystallized with different unit cell parameters, which could account for the structural differences observed. To more precisely compare the structural properties of the peptides, we determined the structure of the AAG·HLA-A2 complex in the same form as the ALG·HLA-A2 complex and at a resolution higher than that of the previous structure (1.7 versus 1.9 Å; Table 1). The new structure was essentially identical to the previous, with the backbones of the peptides from the first and second molecules in the asymmetric units superimposing on those in the earlier structure with root mean square (r.m.s.) deviations of 0.2 and 0.1 Å, respectively (Fig. 2a). Electron density for the peptides was clear (Fig. 2b). As with the earlier AAG·HLA-A2 and ALG·HLA-A2 structures (4), there were no crystallographic contacts to the peptides in either asymmetric unit of the new structure.

TABLE 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Source | Advanced Photon Source 19BM |

| Space group | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 58.2,84.1,84.0 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 90.1, 90.0 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 20–1.68 (1.72–1.68) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.08 (0.47) |

| I/σI | 16.2 (2.1) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.5 (96.9) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (3.6) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20–1.68 |

| No. of reflections | 90,758 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.21/0.17 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 6282 |

| Ligand/ion | 38 |

| Water | 816 |

| B-factors | |

| Protein | 16.0 |

| Ligand/ion | 37.8 |

| Water | 24.6 |

| r.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.64 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | |

| Most favored | 96.2 |

| Allowed | 3.8 |

| Generously allowed | 0.0 |

| Estimated coordinate error (Å)b | 0.068 |

| PDB entry | 3QFD |

a Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

b Based on maximum likelihood.

FIGURE 2.

The center of the ALG but not the AAG peptide shows structural heterogeneity in the HLA-A2 peptide binding groove. a, superimposition of the peptides in both asymmetric units from the new and previously solved AAG·HLA-A2 structures. The color scheme is at the bottom of the figure and maintained in each panel. b, 2Fo − Fc simulated annealing OMIT maps of electron density contoured at 1 σ for the peptides in the asymmetric unit of the new AAG·HLA-A2 structure. The glycine at position 5 is highlighted in green. c, structural comparisons of the centers of the AAG and ALG peptides from the available structures. Peptides are rotated ∼45° toward the viewer relative to their orientation in panels a and b. The panel at the top shows each peptide superimposed, including both molecules in each asymmetric unit. The glycine at position 5 is circled. The bottom left panel shows the various AAG peptides, revealing a spread in the position of the Gly-5 α carbon, but no flip in the backbone. The bottom right panel shows the ALG peptides, revealing not only a greater spread in the position of the Gly-5 α carbon, but also the flip in the backbone at the Gly-5 amide nitrogen and Ile-4 carbonyl oxygen.

In the new AAG structure, the center of the peptide showed slightly greater conformational variance than in the previous structure. Measured by the shift in the Cα of Gly-5 of the peptide, the two molecules in the asymmetric unit of the new AAG·HLA-A2 structure diverged by 0.9 Å, compared with 0.5 Å in the older structure (Fig. 2c, left-hand side). However, the peptide backbone in the new AAG·HLA-A2 structure did not show the conformational flip seen in the ALG·HLA-A2 structure (Fig. 2c, right-hand side). The crystallographic data thus confirm that when bound to HLA-A2, the anchor-modified ALG nonamer possesses greater structural heterogeneity in the center of the peptide than does the native AAG nonamer, resulting in the population of an alternative “flipped” conformation.

NMR Confirms the Center of the ALG Nonamer Adopts Two Distinct Conformations in the HLA-A2 Binding Groove

To examine the conformational properties of the ALG and AAG nonamers bound to HLA-A2 in more detail, we synthesized the peptides with 15N-labeled glycine at position 5 and examined the two peptide·HLA-A2 complexes via NMR. 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation data were collected at 4 °C to ensure the stability of the pMHC complexes over the course of the experiment.

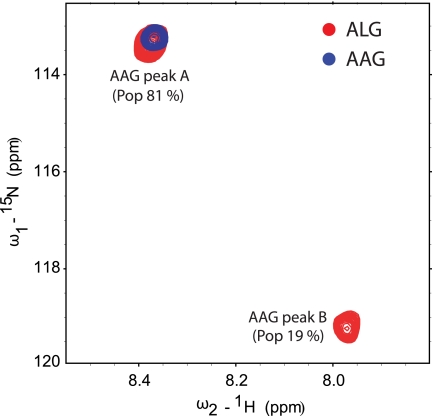

With the ALG nonamer, we observed two distinct peaks (referred to as peak A and peak B) with relative populations of 81% (peak A) and 19% (peak B) (Fig. 3). In contrast, we observed only a single peak with the AAG nonamer. This peak overlapped with that of peak A in the ALG spectrum. These data confirm the crystallographic observation of greater conformational heterogeneity for the center of the ALG nonamer when bound to HLA-A2.

FIGURE 3.

NMR identifies major and minor conformations for the ALG peptide but only a single, overlapping conformation for the AAG peptide when bound to HLA-A2. The figure shows superimposed 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectra for the AAG·HLA-A2 and ALG·HLA-A2 complexes with the Gly-5 amide nitrogen in each peptide 15N-labeled. Data were collected at 4 °C. A single cross-peak was observed in the AAG spectrum. Two cross-peaks (peak A and peak B, with the indicated distribution) were observed in the ALG spectrum. The major peak (peak A) in the ALG spectrum overlapped with the single peak seen in the AAG spectrum.

Can the peaks in the NMR spectra be attributed to the flipped and non-flipped conformers observed in the crystallographic structures? The population distribution in the ALG spectra (81% peak A, 19% peak B) mimics the structural observations in the ALG·HLA-A2 crystal structure, where the flipped conformation was observed as an alternate conformation in just one out of two molecules in the ALG·HLA-A2 asymmetric unit (4). Similarly, only the non-flipped conformation was observed in the AAG·HLA-A2 structures, consistent with the existence of just one peak in the AAG·HLA-A2 NMR spectra. These observations suggest that peak A corresponds to the non-flipped conformation and peak B corresponds to the flipped conformation.

The assignment of the peaks to the flipped and non-flipped conformations of the peptide is further supported when considering chemical environment. The separation of peak A and peak B in the ALG spectrum indicates two different environments for the Gly-5 NH group. The flip in the center of the peptide does indeed place the Gly-5 NH in a substantially different environment. In its non-flipped conformation, the Gly-5 amide nitrogen is highly exposed, with a solvent-accessible surface area of 13.8 Å2 in the ALG·HLA-A2 structure and 13.9 Å2 in the AAG·HLA-A2 structure. This is slightly greater than the solvent-accessible surface area for the central amide nitrogen in an extended pentaglycine peptide (13.4 Å2). In contrast, the flip in the peptide points the Gly-5 NH toward the base of the peptide binding groove, reducing the solvent accessibility of the Gly-5 amide nitrogen over 3-fold to 4.1 Å2.

Chemical shift values move toward their random coil value with increasing solvent accessibility (24). The random coil proton chemical shift for a glycine NH (measured for the central NH in a pentaglycine peptide) at 4 °C is 8.66 ppm (25), close to the value of 8.38 observed for peak A. As the Gly-5 amide nitrogen is exposed to a similar extent as in a pentaglycine random coil, we can attribute peak A to the solvent-exposed non-flipped conformation. Peak B thus corresponds to the flipped conformation seen in the ALG·HLA-A2 structure, shifted due to its removal from bulk solvent.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations Illuminate Differential Peptide Dynamics

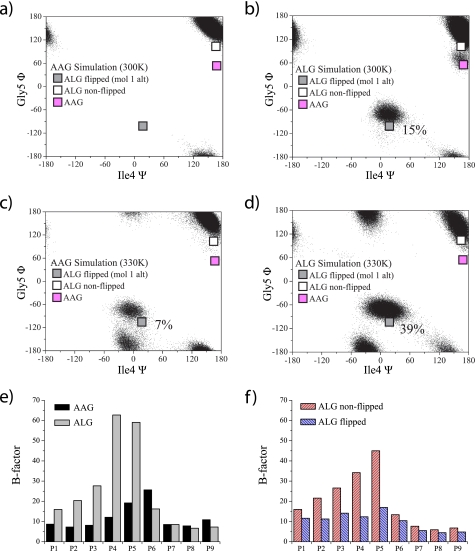

We next examined the conformational behavior of the AAG and ALG peptides bound to HLA-A2 with molecular dynamics simulations. Extending our previous work (4), over the course of 50 ns of simulation time at 300 K, the AAG peptide populated only the crystallographically observed non-flipped conformation (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the ALG peptide populated both the flipped and the non-flipped conformations, with the flipped conformation populated to a level of 15% (Fig. 4b). This was reached by only a single flip, suggestive of a high energy barrier between the two conformations.

FIGURE 4.

Molecular dynamics simulations indicate greater flexibility for the ALG than the AAG peptide when bound to HLA-A2. a, ψ/φ distributions for Gly-5 and Ile-4 for the AAG simulation at 300 K. Only the crystallographically observed non-flipped conformation was observed. b, ψ/φ distributions for Gly-5 and Ile-4 for the ALG simulation at 300 K. In addition to the non-flipped conformation, the flipped conformation was populated at a level of 15%. This occurred due to a single conformational flip that persisted for ∼8 ns. c, increasing the simulation temperature to 330 K resulted in the AAG peptide populating the flipped conformation to 7%. d, increasing the simulation temperature to 330 K increased population of the ALG flipped conformation to 39%. e, B-factors calculated from the simulations indicate greater flexibility across the N-terminal half of the ALG peptide. f, the dominant non-flipped conformation of the ALG peptide is more dynamic than the flipped conformation.

Although the simulation results are consistent with those from crystallography and NMR, the finite simulation time leaves open the possibility that the agreement is fortuitous. To investigate further, we repeated the simulations at the elevated temperature of 330 K, aiming to reduce the energy barriers between the two conformations and facilitate greater sampling (26). Over the course of 50 ns of simulation time at 330 K, the AAG peptide did populate the alternate conformation, but at a low level of 7% (Fig. 4c). The ALG peptide, on the other hand, populated the alternate conformation at a higher level of 39% (Fig. 4d). A second alternate conformation was also observed (near −30°/−160° in the ψ/φ plots in Fig. 4, c and d), indicative of the greater sampling provided by the higher temperature simulation. As with the other alternate conformation, this was populated to a greater extent in the ALG complex than in the AAG complex.

These results confirm the conclusions from the 300 K simulations, indicating the presence of a higher energy flipped conformation for the MART-127–35 peptide. However, the energy of this state is lower in the ALG complex, allowing its greater population and thus visualization via x-ray crystallography and NMR.

We examined the molecular dynamics simulations in more detail by calculating atomic displacement (in the form of B-factors) for the backbones of the AAG and ALG peptides from the 300 K simulation. As expected, the ALG peptide showed increased flexibility when compared with the AAG peptide. The greater flexibility was distributed across the N-terminal half of the peptide, with the highest degree at Ile-4 and Gly-5 (Fig. 4e). Examining the data further, we binned the ALG data into flipped and non-flipped conformations to examine the dynamics of the peptide in each of the two conformations. Surprisingly, the flexibility of the ALG peptide in the non-flipped conformation was higher than that of the flipped conformation. On the other hand, when in the flipped conformation, the ALG peptide was even less dynamic than the native AAG peptide (Fig. 4f). The picture that emerges is that even when they are sharing the same non-flipped conformation, the N-terminal half of the ALG peptide is more flexible than the AAG peptide. When ALG experiences a rare flip, however, the peptide stays relatively rigid.

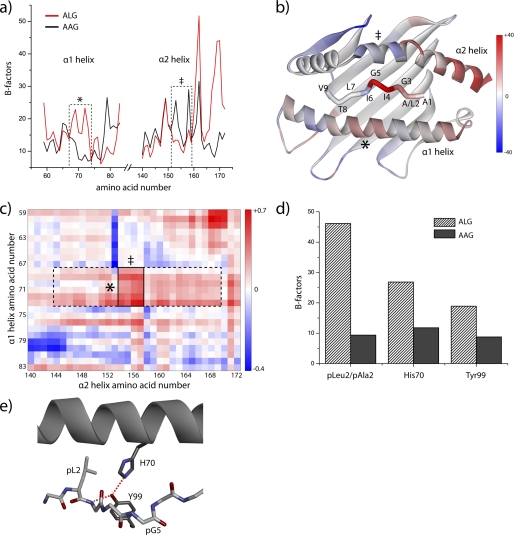

Differential Flexibility between ALG·HLA-A2 and AAG·HLA-A2 Extends to the Helices of the HLA-A2 Peptide Binding Domain

We next examined the HLA-A2 molecule in the AAG and ALG simulations, hypothesizing that modification of the AAG peptide results in altered dynamics of the HLA-A2 peptide binding domain. Clear differences were observed in the average displacement of the atoms in the helices of the peptide binding domain, with an overall 20% greater flexibility in the ALG complex (Fig. 5a). This included greater flexibility in the region of the α1 helix adjacent to the center of the peptide but also reduced flexibility in the region of the α2 helix adjacent to the center of the peptide (both highlighted in Fig. 5a). Increased flexibility was also observed at the C-terminal end of the α2 helix, similar to that observed by Fabian et al. (27) in their analysis of the dynamical consequences of a polymorphism in the base of the binding groove in HLA-B27. Fig. 5b shows the differences in atomic displacement mapped to the structure of the ALG·HLA-A2 complex, illustrating the proximity between the center of the peptide and regions of the α1/α2 helices with altered flexibility.

FIGURE 5.

Anchor modification of the MART-127–35 peptide alters the flexibility of the HLA-A2 peptide binding groove. a, B-factors calculated from the AAG and ALG simulations at 300 K for the α carbons of the HLA-A2 α1 and α2 helices. Flexibility of the central portion of the α1 helix (outlined) is enhanced, whereas flexibility of the central portion of the α2 helix (also outlined) is decreased. b, differences in calculated B-factors between the ALG and AAG simulations mapped to the structure of the pMHC complex. Red indicates a gain in flexibility resulting from anchor modification, and blue indicates a loss in flexibility resulting from anchor modification. The regions corresponding to the centers of the α1 and α2 helices outlined in panel a are indicated. c, heat map of differences in pairwise distance fluctuations between the α carbons of the α1 and α2 helices between the ALG and AAG simulations. Red indicates greater fluctuations resulting from anchor modification. The region outlined with a dashed line highlights the greater fluctuations resulting from the increased mobility of the center of the α1 helix. The smaller region outlined with a solid line indicates the significantly enhanced distance fluctuations between the regions of the α1 and α2 helices immediately adjacent to the center of the peptide. d, averaged B-factors of atoms of the P2 side chains and those of His-70 and Tyr-99 in the AAG and ALG simulations at 300 K. The greater flexibilities in the ALG complex indicate a direct connection between dynamics at the position 2 anchor, the peptide backbone, and the center of the α1 helix. e, structural relationship between Leu-2 in the HLA-A2 P2 pocket and His-70 and Tyr-99 of the peptide binding groove. Red dashed lines show hydrogen bonds between Tyr-99 and His-70 and Gly-3 of the peptide.

As class I MHC α1 and α2 helices tend to move in collective motions that can be summarized as a “breathing” of the peptide binding groove (27–29), we asked how distances between the α carbons of pairs of amino acids along the α1 and α2 helices changed over the course of the simulations. For the AAG and ALG simulations at 300 K, we first computed the average distances between the α carbons of all pairs of amino acids along the α1 and α2 helices. The results for the AAG and ALG simulations were nearly identical (supplemental Fig. 1), indicating that anchor modification did not appreciably alter the time-averaged structure of the HLA-A2 peptide binding domain, consistent with the crystallographic structures. However, differences were observed when we examined the root mean square (r.m.s.) fluctuations around the average distances. Fig. 5c shows the differences in r.m.s. fluctuations between the ALG and AAG simulations for all pairs of α carbons across the α1 and α2 helices plotted as a heat map. The fluctuations were generally greater in the ALG simulation, in some places as much as four standard deviations above the mean. The results were numerically significant, as indicated by the differences in the histograms of the distance fluctuations in the two simulations (supplemental Fig. 1).

The horizontal band outlined in Fig. 5c with dashed lines showing greater fluctuations in the ALG simulation between Lys-68 and Thr-73 on the α1 helix and Lys-144 and Leu-169 on the α2 helix is of particular interest. This region of the α1 helix corresponds to that with higher atomic displacements highlighted in Fig. 5, a and b, and as noted above, it is adjacent to the center of peptide. The most intense portion of this band (outlined with a solid line) reflects fluctuations between this region of the α1 helix and the region of the α2 helix with reduced flexibility that is directly opposite. We conclude from this that substitution of Ala-2 with leucine in the MART-1 peptide leads to enhanced fluctuations across the portion of the peptide binding groove that surrounds the center of the peptide.

How might anchor modification of the peptide lead to greater fluctuations of the HLA-A2 peptide binding groove? In the ALG simulation, the leucine side chain at position 2 of the peptide was mobile within the HLA-A2 P2 pocket (Fig. 5d). Due to the need to avoid steric clashes, the greater dynamics of leucine 2 induced greater dynamics in the side chain of His-70, which forms one “wall” of the P2 pocket and is within the region of the α1 helix with the greatest degree of flexibility in the ALG·HLA-A2 complex. The movements in Leu-2 and His-70 also impacted the side chain mobility of Tyr-99, which is at the base of the P2 pocket and hydrogen-bonds to His-70 as well as Gly-3 of the peptide. Thus, when compared with alanine, the bulkier and more dynamic leucine in the HLA-A2 P2 pocket can be directly connected to regions of the peptide backbone and HLA-A2 α1 helix that possess greater dynamics in the ALG·HLA-A2 complex.

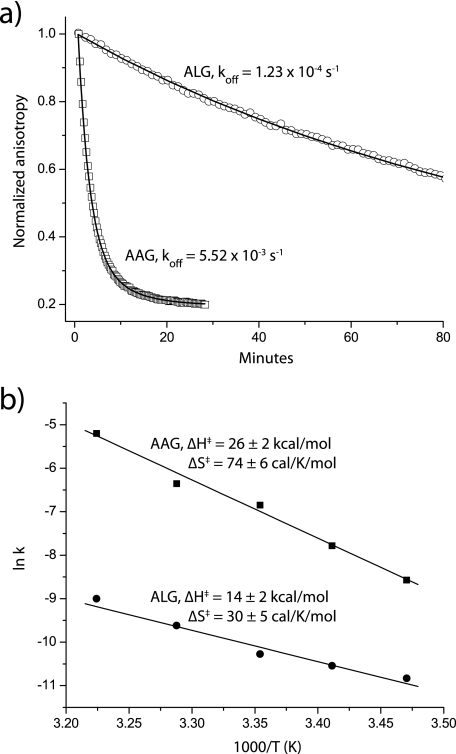

Dissociation Thermodynamics Support the Greater Flexibility of the ALG·HLA-A2 Complex

Lastly, we compared the thermodynamics of the AAG and ALG complexes using a quantitative peptide dissociation assay based on fluorescence anisotropy, using peptides fluorescently labeled at position 7 (21, 22). The labeled ALG peptide had a substantially slower rate of dissociation than the labeled AAG peptide, ranging from 10-fold slower at 15 °C to 45-fold slower at 37 °C (the initial anisotropy of the ALG complex was 10–20% lower at every temperature, consistent with the greater flexibility of the peptide) (Fig. 6a). We next used an Eyring analysis of dissociation rates measured from 15 to 37 °C to determine the thermodynamics of dissociation (21, 22). As shown in Fig. 6b, the reduced dissociation rate of the ALG peptide was attributable to a less favorable activation entropy, i.e. when compared with the native AAG peptide, the ALG complex gains less entropy as the peptide moves from the bound state to the binding transition state. An interpretation of these data consistent with the molecular dynamics, NMR, and structural data is that the smaller gain in entropy for the ALG peptide arises from a more dynamic bound state. Differences in solvation between the two transition states could also play a role given the more hydrophobic leucine at position 2 of the ALG peptide. This could help explain the more favorable enthalpy change for dissociation of the ALG peptide. However, the concordance between the various sets of data suggests that dynamical differences between the ALG and AAG pMHC complexes are a significant contributor to the dissociation thermodynamics.

FIGURE 6.

Peptide dissociation thermodynamics are consistent with a higher entropy for the ALG·HLA-A2 complex. a, peptide dissociation at 37 °C measured by fluorescence anisotropy. The much slower dissociation of the ALG peptide is readily apparent. b, Eyring analysis of peptide dissociation data from 15 to 37 °C. The activation thermodynamics indicate that the ALG·HLA-A2 complex peptide gains less entropy moving from the bound to the transition state, consistent with the greater flexibility seen in the ALG·HLA-A2 complex.

DISCUSSION

Anchor modification of peptides is a common strategy for enhancing peptide-MHC binding affinity and is frequently used in the design of peptide-based vaccine candidates for infectious disease and cancer. However, anchor modification is not always successful at enhancing peptide immunogenicity. Failures are often attributed to the high sensitivity of the T cell receptor toward subtle chemical changes in antigenic peptides, although the underlying mechanisms are usually not well understood.

To examine how subtle peptide modifications can negatively impact TCR recognition, we explored one of the most dramatic failures of the anchor modification strategy reported: despite substantially improving the interaction with HLA-A2, replacement of the suboptimal alanine at position 2 of the nonameric MART-127–35 melanoma antigen with leucine considerably reduces or abolishes immunogenicity with a wide range of clonally diverse T cells (2, 4, 5). This negative outcome has led to the use of other MART-1 antigens in clinical trials for the immunological treatment of melanoma (e.g. Ref. 30) despite evidence that the nonamer is the clinically relevant antigen in HLA-A2+ individuals (31).

The loss in immunogenicity with the modified MART-127–35 nonamer is attributable to weaker TCR binding, as demonstrated here in a direct binding experiment with the DMF5 TCR. However, anchor modification has only a minor structural effect on the peptide, leading to the partial occupancy of an alternative flipped conformation for the central glycine at position 5 of the peptide. In the structures of two different TCRs bound to the MART-127–35 nonamer (32), there are no interactions with the region of the peptide that is altered. Further, as T cells that are sensitive to anchor modification also recognize the decameric MART-126–35 peptide, which possesses substantially greater structural variation in this region (4), structural aspects alone cannot easily explain the poor recognition of the modified nonamer.

The data presented here suggest a more general effect: rather than altering the structure per se, anchor modification of the MART-127–35 peptide enhances ligand flexibility. In addition to inducing heterogeneity in the peptide, the enhanced flexibility extends to the HLA-A2 α1 and α2 helices, resulting in greater breathing of the peptide binding domain. The fluctuations in the peptide and the peptide binding domain appear linked, with the enhanced flexibility of the helices reducing steric barriers that otherwise hinder peptide movement. As protein flexibility translates into conformational entropy, the result is that the complex with the modified peptide possesses higher entropy.

The higher entropy of the complex with the modified peptide will have two consequences. First, as the overall entropic penalty for binding will be reduced, binding of the peptide to HLA-A2 will be improved to a degree beyond that expected solely from the tighter packing and burial of hydrophobic surface associated with an alanine-to-leucine substitution at the P2 anchor position. The peptide binding data are consistent with this; anchor modification of the MART-127–35 peptide increases peptide binding to HLA-A2 by 40-fold (2). For comparison, the same alanine-to-leucine P2 anchor modification in the MART-126–35 EAA decamer leads to a much smaller 2-fold enhancement in binding affinity (2). Importantly, there are no indications that the modification in the decamer alters pMHC structure or dynamics, and it does not negatively impact recognition by MART-1-specific T cells (4, 6).

However, in addition to favorably impacting peptide binding to HLA-A2, a higher entropy for the complex with the modified MART-127–35 peptide will negatively impact TCR binding. TCRs contact both peptide and MHC, and the majority of TCRs whose structures have been determined “focus” on the center of the peptide and the α1/α2 helices (33). This is true for the DMF5 TCR used here, as well as the unrelated MART-127–35-specific DMF4 TCR (32). As the formation of TCR-pMHC contacts in this region will necessitate a reduction in binding site flexibility, the enhanced dynamics of the modified pMHC complex will result in a less favorable entropy change for TCR binding, translating into reduced affinity. This effect has been seen with the A6 TCR, which recognizes the Tax and Tel1p peptides presented by HLA-A2. The Tel1p peptide induces greater flexibility in the HLA-A2 α2 helix, and as anticipated, receptor binding occurs with a less favorable binding entropy change (ΔΔS° = −3 cal/K/mol) (34).

In the case studied here, without a high affinity MART-127–35-specific TCR to quantify binding thermodynamics, the extent of the increased entropic penalty for TCR binding resulting from anchor modification of the peptide cannot be quantified. Further, as different TCRs will require different contacts to pMHC, the overall impact will likely vary with different receptors. However, the DMF5 TCR used here provides some guidance. Anchor modification to the MART-127–35 peptide weakens the KD of the DMF5 TCR from 68 μm to greater than 3.3 mm, amounting to an unfavorable loss in binding free energy of at least 2.3 kcal/mol at 25 °C. If we assume that this value is solely attributable to conformational entropy, it translates into a minimum entropic penalty of 8 cal/K/mol. In absolute terms, this is not large as reported ΔS° values for TCR recognition of pMHC span a 100 cal/K/mol range (35). However, given the relatively weak affinities and thus binding free energies associated with TCR recognition of pMHC (and self-antigens in particular) (36), the consequence of even a small gain in the entropic penalty for binding will be significant. A 5 cal/K/mol increase in binding ΔS° will convert TCR binding affinities occurring in the range of 50–100 μm (a range typical for TCR recognition of self-antigens) to 600–1200 μm, weaker than that typically expected to result in a functional T cell response.

This analysis leads us to consider a more refined view of TCR specificity. Receptor specificity, typically defined by changes in peptide composition translating into a loss of recognition in functional assays, is usually thought to arise from either the disruption of favorable interactions or the introduction of unfavorable interactions between TCR and peptide. This interpretation evokes the commonly held view that TCRs are highly tuned toward the structure of a particular antigen. We propose that in the case of TCRs that recognize MART-1 antigens, this is not the case. The majority of these TCRs can in fact tolerate substantial structural variation, as seen by the widespread cross-reactivity between the 27–35 AAG nonamer and the structurally divergent 26–35 EAA decamer (2, 4, 5), recently visualized in crystallographic structures of the DMF4 and DMF5 TCRs (32). Rather, “highly specific” TCR recognition of the MART-1 nonamer revealed by anchor modification may arise because moderate TCR affinity allows what may be a relatively small increase in the entropic cost of binding to weaken TCR affinity to levels that substantially weaken or fully ablate the immunological response.

Could this alternative view of specificity be a more general phenomenon? It is notable that, at least for class I MHC molecules, the flexibility of the peptide binding domain seems to be readily tunable via peptide or MHC alterations. Complementing the data presented here, as noted above, we recently demonstrated that the flexibility of the HLA-A2 α2 helix differs when the Tax and Tel1p peptides are bound (34). Fabian et al. (27, 37, 38) have demonstrated that allelic variations as well as peptide modifications induce different degrees of flexibility in HLA-B27 subtypes. It is thus possible that alterations in peptide and MHC flexibility stemming from changes to antigenic peptides could explain other cases where T cells have been shown to “sense” modifications to antigenic peptides despite any clear indications of structural changes (e.g. Refs. 39 and 40).

Altogether, these results suggest that further studies of the dynamical consequences of peptide modifications are needed, particularly in the design and optimization of peptide-based vaccines. Although predicting dynamical effects from structural alterations is challenging, the use of molecular simulations in conjunction with structural information and other tools for quantifying protein dynamics may be useful in such endeavors. Lastly, alterations of pMHC flexibility that weaken TCR binding could also serve as a mechanism for viral and tumor escape from immune destruction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia Piepenbrink for outstanding technical assistance and Daniel R. Scott for critical comments on the manuscript. Results shown in this study are derived from work performed at the Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. The Argonne National Laboratory is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the United States Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant GM067079 from the NIGMS (to B. M. B.). This work was also supported by Grant MCB0448298 from the National Science Foundation and Grant RSG-05-202-01-GMC from the American Cancer Society.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3QFD) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

The peptides used in this study are as follows: AAG, MART-127–35 nonamer (AAGIGILTV); ALG, anchor-modified MART-127–35 nonamer (ALGIGILTV); EAA, MART-126–35 decamer (EAAGIGILTV).

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- pMHC

- peptide/MHC complex

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- BIS-TRIS

- 2-(bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino)-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yu Z., Theoret M. R., Touloukian C. E., Surman D. R., Garman S. C., Feigenbaum L., Baxter T. K., Baker B. M., Restifo N. P. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 114, 551–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Valmori D., Fonteneau J. F., Lizana C. M., Gervois N., Liénard D., Rimoldi D., Jongeneel V., Jotereau F., Cerottini J. C., Romero P. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 1750–1758 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parkhurst M. R., Salgaller M. L., Southwood S., Robbins P. F., Sette A., Rosenberg S. A., Kawakami Y. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 2539–2548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borbulevych O. Y., Insaidoo F. K., Baxter T. K., Powell D. J., Jr., Johnson L. A., Restifo N. P., Baker B. M. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 1123–1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Derré L., Ferber M., Touvrey C., Devevre E., Zoete V., Leimgruber A., Romero P., Michielin O., Lévy F., Speiser D. E. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 7635–7645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sliz P., Michielin O., Cerottini J. C., Luescher I., Romero P., Karplus M., Wiley D. C. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 3276–3284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Romero P., Valmori D., Pittet M. J., Zippelius A., Rimoldi D., Lévy F., Dutoit V., Ayyoub M., Rubio-Godoy V., Michielin O., Guillaume P., Batard P., Luescher I. F., Lejeune F., Liénard D., Rufer N., Dietrich P. Y., Speiser D. E., Cerottini J. C. (2002) Immunol. Rev. 188, 81–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis-Harrison R. L., Armstrong K. M., Baker B. M. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346, 533–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boulter J. M., Glick M., Todorov P. T., Baston E., Sami M., Rizkallah P., Jakobsen B. K. (2003) Protein Eng. 16, 707–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khan A. R., Baker B. M., Ghosh P., Biddison W. E., Wiley D. C. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 6398–6405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piepenbrink K. H., Gloor B. E., Armstrong K. M., Baker B. M. (2009) Methods Enzymol. 466, 359–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borbulevych O. Y., Baxter T. K., Yu Z., Restifo N. P., Baker B. M. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 4812–4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly A. E., Ou H. D., Withers R., Dötsch V. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 12013–12019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salzmann M., Pervushin K., Wider G., Senn H., Wüthrich K. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13585–13590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Czisch M., Boelens R. (1998) J. Magn. Reson. 134, 158–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Case D. A., Cheatham T. E., 3rd, Darden T., Gohlke H., Luo R., Merz K. M., Jr., Onufriev A., Simmerling C., Wang B., Woods R. J. (2005) J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1668–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Binz A. K., Rodriguez R. C., Biddison W. E., Baker B. M. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 4954–4961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baxter T. K., Gagnon S. J., Davis-Harrison R. L., Beck J. C., Binz A. K., Turner R. V., Biddison W. E., Baker B. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29175–29184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson L. A., Heemskerk B., Powell D. J., Jr., Cohen C. J., Morgan R. A., Dudley M. E., Robbins P. F., Rosenberg S. A. (2006) J. Immunol. 177, 6548–6559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vranken W. F., Rieping W. (2009) BMC Struct. Biol. 9, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Merutka G., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 5, 14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruccoleri R. E., Karplus M. (1990) Biopolymers 29, 1847–1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fabian H., Huser H., Narzi D., Misselwitz R., Loll B., Ziegler A., Böckmann R. A., Uchanska-Ziegler B., Naumann D. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 376, 798–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zacharias M., Springer S. (2004) Biophys. J. 87, 2203–2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Petrone P. M., Garcia A. E. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 338, 419–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Phan G. Q., Touloukian C. E., Yang J. C., Restifo N. P., Sherry R. M., Hwu P., Topalian S. L., Schwartzentruber D. J., Seipp C. A., Freezer L. J., Morton K. E., Mavroukakis S. A., White D. E., Rosenberg S. A. (2003) J. Immunother. 26, 349–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skipper J. C., Gulden P. H., Hendrickson R. C., Harthun N., Caldwell J. A., Shabanowitz J., Engelhard V. H., Hunt D. F., Slingluff C. L., Jr. (1999) Int. J. Cancer 82, 669–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borbulevych O. Y., Santhanagopolan S. M., Hossain M., Baker B. M. (2011) J. Immunol. 187, 2453–2463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rudolph M. G., Stanfield R. L., Wilson I. A. (2006) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24, 419–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borbulevych O. Y., Piepenbrink K. H., Gloor B. E., Scott D. R., Sommese R. F., Cole D. K., Sewell A. K., Baker B. M. (2009) Immunity 31, 885–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Armstrong K. M., Insaidoo F. K., Baker B. M. (2008) J. Mol. Recognit. 21, 275–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davis M. M., Boniface J. J., Reich Z., Lyons D., Hampl J., Arden B., Chien Y. (1998) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 523–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fabian H., Huser H., Loll B., Ziegler A., Naumann D., Uchanska-Ziegler B. (2010) Arthritis Rheum. 62, 978–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fabian H., Loll B., Huser H., Naumann D., Uchanska-Ziegler B., Ziegler A. (2011) FEBS J. 278, 1713–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cole D. K., Edwards E. S., Wynn K. K., Clement M., Miles J. J., Ladell K., Ekeruche J., Gostick E., Adams K. J., Skowera A., Peakman M., Wooldridge L., Price D. A., Sewell A. K. (2010) J. Immunol. 185, 2600–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ding Y. H., Baker B. M., Garboczi D. N., Biddison W. E., Wiley D. C. (1999) Immunity 11, 45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goddard T. D., Kneller D. G. (2007) Sparky 3.113, University of California, San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.