Background: Cyclophilin D, a known mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) regulator, is associated with cellular protection.

Results: Mutation of cysteine 203 of cyclophilin D inhibits mPTP opening and improves cell viability.

Conclusion: Cysteine 203 of cyclophilin D is a critical residue for mPTP activation.

Significance: This work provides novel mechanistic insights into mPTP regulation.

Keywords: Adenovirus, Mitochondria, Mutant, Nitric Oxide, Post-translational Modification, Cyclophilin D, Cysteine Modification, Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore, Redox, S-nitrosylation

Abstract

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening plays a critical role in mediating cell death during ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. Our previous studies have shown that cysteine 203 of cyclophilin D (CypD), a critical mPTP mediator, undergoes protein S-nitrosylation (SNO). To investigate the role of cysteine 203 in mPTP activation, we mutated cysteine 203 of CypD to a serine residue (C203S) and determined its effect on mPTP opening. Treatment of WT mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with H2O2 resulted in an 50% loss of the mitochondrial calcein fluorescence, suggesting substantial activation of the mPTP. Consistent with the reported role of CypD in mPTP activation, CypD null (CypD−/−) MEFs exhibited significantly less mPTP opening. Addition of a nitric oxide donor, GSNO, to WT but not CypD−/− MEFs prior to H2O2 attenuated mPTP opening. To test whether Cys-203 is required for this protection, we infected CypD−/− MEFs with a C203S-CypD vector. Surprisingly, C203S-CypD reconstituted MEFs were resistant to mPTP opening in the presence or absence of GSNO, suggesting a crucial role for Cys-203 in mPTP activation. To determine whether mutation of C203S-CypD would alter mPTP in vivo, we injected a recombinant adenovirus encoding C203S-CypD or WT CypD into CypD−/− mice via tail vein. Mitochondria isolated from livers of CypD−/− mice or mice expressing C203S-CypD were resistant to Ca2+-induced swelling as compared with WT CypD-reconstituted mice. Our results indicate that the Cys-203 residue of CypD is necessary for redox stress-induced activation of mPTP.

Introduction

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP)2 plays a critical role in mediating cell death during ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (1–3), and inhibition of mPTP is the target of cytoprotective signaling in various organs, including the heart, brain, kidney, and liver (4–8). mPTP has been suggested to be a multiprotein complex that can form a nonspecific pore, which renders the inner mitochondrial membrane permeable to molecules smaller than 1500 daltons (9–11). The opening of mPTP during I/R injury results in loss of membrane potential, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, matrix swelling, ATP depletion, and production of reactive oxygen species, ultimately leading to cell death. mPTP opening is reported to be a major cause of reperfusion injury, and thus it is an important target for cytoprotection. Interestingly, mPTP has been shown to be redox-sensitive (12–14). Low levels of N-ethylmaleimide can reduce susceptibility of mPTP opening, but high levels enhance mPTP opening (15). It also has been shown previously that critical thiols in the pore can be oxidized and facilitate mPTP opening (16–20). Despite extensive research, the molecular identity of the mPTP remains controversial.

At present, cyclophilin D (CypD) is the only defined element of the mPTP, serving as a regulator of mPTP but not as a pore component (3). Mitochondria isolated from CypD−/− mice have been shown to be more resistant to mPTP opening than WT mice, which correlates with a reduction in cell death during I/R in vivo (3, 21). CypD is a mitochondrial matrix protein from a family of cyclophilin proteins that have peptidylprolyl isomerase (PPIase) activity, catalyzing the cis-trans isomerization of peptidylprolyl bonds. In addition, CypD catalyzes the folding of newly imported mitochondrial proteins. In light of the redox sensitivity of mPTP, it is also interesting that CypD has recently been shown to be regulated by redox-sensitive processes (12–14).

S-nitrosylation (SNO), the covalent attachment of an NO moiety to a protein thiol group, is a reversible, redox-dependent post-translational modification that has been shown to reduce I/R injury (22–24). NO donors such as GSNO have been shown to increase SNO of a number of proteins. SNO could exert protective effects by modifying cysteine residues and thereby shielding crucial cysteine residues from further irreversible modification such as oxidation in I/R injury (23). Moreover, SNO has the ability to modify the activity of target proteins such as enzymes that are involved in oxidative phosphorylation (25–27). In addition, SNO has also been shown to modulate the activity of proteins involved in apoptosis and oxidative stress (28–29). Studies show that depending on the concentration and redox state of the cell, NO can enhance or inhibit the mPTP (30–32). SNO of proteins occurs with cardioprotection (33). Kohr et al. (34) recently demonstrated that treatment of heart homogenates with GSNO results in SNO of cysteine 203 on CypD. These observations led us to hypothesize that Cys-203 of CypD might be important in CypD regulation of the mPTP. Therefore, the goal of this work was to determine the effect of mutation of Cys-203 of CypD on mPTP opening. In this work, we show that mutation of the SNO site Cys-203 of CypD significantly reduced mPTP opening in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), suggesting that Cys-203 of CypD is required for mPTP opening.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

S-Nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) was purchased from Calbiochem/EMD Bioscience (La Jolla, CA). Hydrogen peroxide, trypsin, glutamate, malate, carbonyl cyanide p-chlorophenylhydrazone, and all other standard chemicals (unless indicated otherwise) were purchased from Sigma. DMEM was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Hank's buffered salt solution and tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester were purchased from Invitrogen. Protease/phosphatase inhibitor tablets were purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Sources for other reagents/chemicals are specified for each procedure outlined below.

Animals

All animals were treated and cared for in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, revised 1996), and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6 mice (12 to 15 weeks) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME).

Heart Perfusion

After anesthesia, mouse hearts were excised and quickly placed in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer: 120 mmol of NaCl, 11 mmol of d-glucose, 25 mmol of NaHCO3, 1.75 mmol of CaCl2, 4.7 mmol of KCl, 1.2 mmol of MgSO4, and 1.2 of mmol KH2PO4. The aorta was cannulated on a Langendorff apparatus and the heart was perfused in retrograde fashion with oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer at 37 °C. After 20 min of equilibrium perfusion, hearts were perfused for an additional 40 min or subjected to ischemic preconditioning (four cycles of 5 min of ischemia and 5 min of reperfusion). At the end of the perfusion period, hearts were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Crude mouse heart homogenates were prepared as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, each heart was powdered on liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Powdered hearts were then resuspended in 1.5 ml of homogenization buffer containing the following: sucrose (300 mm), HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.7 (250 mm), EDTA (1 mm), and neocuproine (0.1 mm). An EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was introduced just before use. Samples were then homogenized via Dounce glass homogenization on ice and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 2 min. The supernatant was recovered as total crude homogenate.

S-Nitrosylation Protein Identification and Site Determination with S-Nitrosylation Resin-assisted Capture

S-Nitrosylated proteins were identified using the SNO-resin-assisted capture method as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, samples (1 mg) were diluted in HEPES EDTA neocuproine buffer with 2.5% SDS and an EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet (Roche Diagnostics). Samples were then incubated with 50 mmol/liter N-ethylmaleimide for 20 min at 50 °C to block unmodified (i.e. free) thiol groups; N-ethylmaleimide was removed via acetone precipitation. Samples were resuspended in HEN buffer with 1% SDS and incubated with 20 mmol/liter ascorbate and thiopropyl-Sepharose resin (GE Healthcare) for 4 h at room temperature to reduce and capture SNO cysteine residues. Samples were then subjected to tryptic digestion, and the remaining resin-bound peptides were eluted via 10 mmol/liter DTT and identified using an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The MASCOT search engine was used for protein identification as described previously (33, 34).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

The expression vector of mutated C203S-CypD was constructed using a QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using plasmid pCMV6-XL5-CypD as a template. The human full-length CypD clone was constructed using the pCMV6-XL5 mammalian expression vectors obtained from OriGene (Rockville, MD). The forward (TCATCACAGACTCTGGCCAGTTGAGC) and reverse complement (CTCAACTGGCCAGAGTCTGTGATGAC) primers containing a base mismatch (indicated by boldface letters) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (San Diego, CA). DNA sequencing was confirmed using VP1.5 (GGACTTTCCAAAATG-TCG) and XL 39 (ATTAGGACAAGGCTGGT-GGG) primers by Genewiz, Inc. (South Plainfield, NJ).

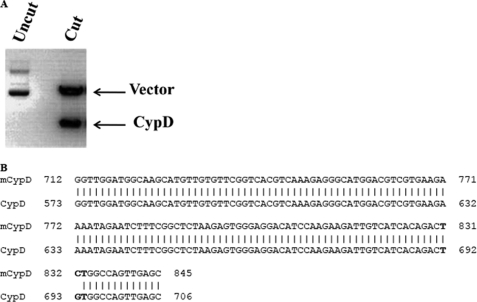

The mutated C203S-CypD plasmid was digested with the restriction enzyme NotI to release the CypD insert, and the resulting sample was analyzed on 1% agarose gel. As expected, after digestion with NotI, the CypD plasmid generated two fragments: the pCMV6-XL5 vector (4.7 kb) and CypD insert (1.7 kb) (Fig. 3A). The mutation was further confirmed by DNA sequencing and analyzed using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST). The cysteine corresponding codon TGT was replaced with the serine corresponding codon TCT (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Confirmation of C203S-CypD mutation by restriction digestion and DNA sequencing. In A, 1 μg of mutated CypD (mCypD) plasmid was digested with 2 units of restriction enzyme, NotI, at 37 °C for 1 h. The resulting reaction and undigested samples were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. A representative ethidium bromide stained gel is shown. In B, a mutated C203S-CypD plasmid sample was sequenced to confirm the site-directed mutagenesis. The replaced serine corresponding codon TCT is in boldface.

MEF Isolation

MEFs were isolated from CypD+/+ and CypD−/− embryos from 12.5 to 14.5-day-pregnant mice by trypsin digestion, as described previously (3). MEFs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Transfection

Isolated WT MEFs were transfected with pCMV-XL5 (control vector) (OriGene, Rockville, MD). CypD−/− MEFs were transfected with control vector, WT CypD, or mutated C203S-CypD plasmids using Fugene HD (Roche Diagnostics). MEFs were cultured for 48 h prior to experiments.

LIVE/DEAD Viability

After transfections, MEFs were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 6 h to induce cell death. Cell death was assessed using the LIVE/DEAD viability kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

mPTP Assay

mPTP opening in MEFs was assessed using the MitoProbe Transition Pore Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were loaded with 40 nm of calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (AM) at 37 °C for 15 min. Cells were then washed with Hank's buffered salt solution and were treated with 0.4 mm CoCl2 or 0.4 mm CoCl2 plus 1 mm H2O2 for 10 min at 37 °C. The samples were then analyzed using a CYAN flow cytometer with appropriate excitation and emission filters for fluorescein. The change in fluorescence intensity between samples incubated with only calcein AM/CoCl2 and samples incubated with calcein AM/CoCl2+H2O2 indicates mPTP-induced opening by H2O2.

Generation of Recombinant CypD and Mutated CypD Adenoviral Particles

Adenoviral CypD and mutated CypD were generated using the AdEasy adenoviral vector system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Adenovirus stocks were further amplified in AD-293 cells, and adenovirus titers were determined using the AdEasy viral titer kit (Genomics), an enzyme-linked immunoassay, according the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vivo Gene Transfer

Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to the liver was carried out by tail vein injection of 5.4 × 107 pfu/g of adenoviral particles. Three experimental groups were evaluated after 72 h. In group 1, CypD−/− mice received intravenous injection of adenovirus CMV-GFP (control). In group 2, CypD−/− mice received a recombinant adenovirus encoding WT CypD. In group 3, CypD−/− mice were injected with a recombinant adenovirus encoding mutated C203S-CypD.

Mitochondria Isolation from Liver Tissue

Liver tissue was rinsed four times with PBS, and the tissue was homogenized in 225 mm mannitol, 75 mm sucrose, 5 mm MOPS, 0.5 mm EGTA, and 2 mm taurine (pH 7.25) (Buffer B) with protease/phosphatase inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 × g, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 11,000 × g to pellet the mitochondria. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in Buffer B and protease/phosphatase inhibitors.

Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Measurement

Oxygen consumption was measured in a chamber connected to a Clark-type O2 electrode (Instech) and O2 monitor (Model 5300, YSI, Inc.) at 25 °C. Mitochondria were incubated in respiration buffer (120 mm KCl, 5 mm MOPS, 1 mm EGTA, 5 mm KH2PO4, and 0.2% BSA). After addition of 10 mm glutamate/2 mm malate, state 3 respiration was measured by addition of 0.5 mm ADP.

Mitochondrial Swelling and Calcium Retention Capacity Assays

Ca2+-induced swelling of isolated liver mitochondria were measured spectrophotometrically as a decrease in absorbance at 540 nm. Isolated liver mitochondria (100 μg) were washed twice with Buffer B with protease/phosphatase inhibitors without EGTA and resuspended in swelling buffer (120 mm KCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl, 5 mm MOPS, 5 mm Na2HPO4, 10 mm glutamate, and 2 mm malate) in a total volume of 200 μl. Pore opening was induced by 250 μm of CaCl2 in the presence and absence of 200 nm cyclosporine A (CsA), a known mPTP inhibitor, and measured at 540 nm.

In addition, mPTP opening of MEFs expressing WT CypD or mutated CypD was assessed using the calcium retention capacity (CRC) assay. To measure CRC of MEFs, after transfections, MEFs were harvested using trypsin, washed in PBS, and permeabilized with 0.002% digitonin for 10 min. After permeabilization of the plasma membrane, MEFs were washed once in PBS before being resuspended in the swelling buffer. CRC was assessed using 10 μm fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Calcium Green-5N (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) with the addition of 5 μm Ca2+ pulses to induce mPTP opening.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement

Membrane potential of isolated mitochondria was measured using 1 μm tetramethylrhodamine, ethyl ester in a quenching mode in 200 μl of swelling buffer. To dissipate the membrane potential, 1 μm protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-chlorophenylhydrazone was used.

PPIase Activity

PPIase activity was measured spectrophometrically using recombinant CypD (Abnova, Walnut, CA) with buffer (50 mm HEPES, 100 mm NaCl, pH 8.0). Immediately before assaying activity, freshly prepared α-chymotrypsin (60 mg/ml, final concentration, 6 mg/ml, Sigma) was added. The freshly made PPIase substrate N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe p-nitroanilide (substrate) (Sigma) was dissolved in the solvent trifluoroethanol with LiCl (470 mm) to a 3 mm stock concentration. The PPIase substrate was added to the reaction to give a final concentration of 75 nm. The absorbance was recorded at 410 nm. All assay solutions/reagents were at 4 °C. Data were fitted into a first-order rate equation. The assay relies on the ability of α-chymotrypsin to release p-nitroanilide from N-succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe p-nitroanilide only if the bond on the N-terminal side of the proline side is in the trans conformation. Addition of the substrate in the presence of α-chymotrypsin causes a very rapid release of p-nitroanilide since a large proportion (70–80%) of the substrate is in the trans conformation, followed by the slower release of p-nitroanilide as the cis isomer spontaneously isomerizes to the trans form. CypD enhances the rate of the second stage of the reaction. The rate constant of the second stage of the reaction represents PPIase activity. Data obtained in the presence of 20 nm CypD were fitted to a first order rate equation to obtain the kobs as described (13). The spontaneous PPIase activity or non-enzymatic rate (Ko, in the absence of recombinant CypD) was also calculated from each independent experiment. The data presented as kobs − Ko.

Western Blot

After 48 h of transfection, proteins were extracted in cold radioimmune precipitation assay buffer plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific). Equivalent amounts of protein (40 μg) from each sample were separated on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Gel transfer efficiency and equal loading were verified using reversible Ponceau S staining. The resulting blots were probed with cyclophilin D and β-ATP synthase antibodies (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR) or β-actin antibody (Sigma).

Statistical Analyses

All data were expressed as mean ± S.E. The Student's two-sample t test or one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's post hoc analyses were used for comparison of differences between groups, and a p value 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

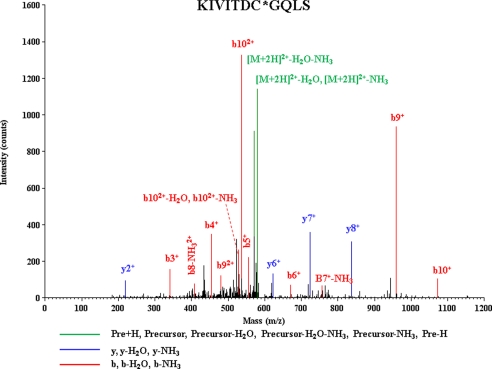

S-Nitrosylation of CypD

Protein SNO has been shown to play important role in cardioprotection (22–24, 33, 34). To determine whether CypD was S-nitrosylated with cardioprotection, we subjected Langendorff perfused hearts to ischemic preconditioning as described in the methods. Using a modified SNO-Resin-Assisted Capture method (33, 34), we found S-nitrosylation of CypD on cysteine 203 (KIVITDC*GQLS) (asterisk indicates the S-nitrosylated cysteine residue). A representative spectrum for CypD identification is shown in Fig. 1. This finding is consistent with our previous data (34) showing that Cys-203 is S-nitrosylated in heart homogenates following GSNO treatment.

FIGURE 1.

MS/MS spectra for CypD. Representative MS/MS spectra showing fragmentation of the KIVITDC*QLS peptide (IonScore, 38). Peaks in the spectrum that are marked red correspond to matched b ions and peaks that are marked blue correspond to matched y ions. The number paired with each ion identification (i.e. b2, y4, etc.) indicates the number of amino acids present on N-terminal fragments for b ions and C-terminal fragments for y ions. This peptide identification was observed with ischemic preconditioning in two of five biological replicates; this modification was not observed in any of the hearts with control perfusion.

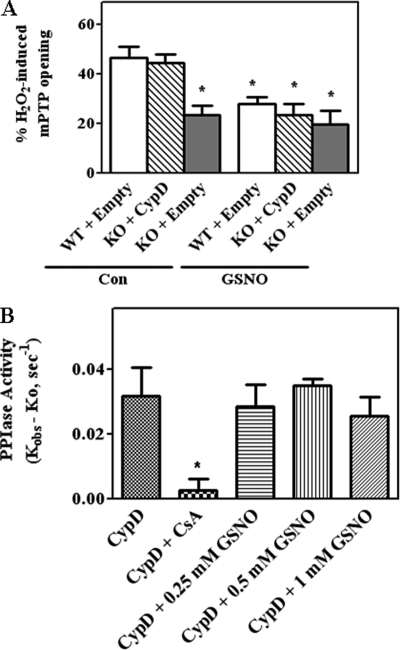

GSNO Inhibited mPTP Opening

Addition of NO donors, which lead to an increase in protein SNO, have been shown to be cytoprotective and to reduce mPTP opening (25, 33). As CypD has the ability to undergo SNO at Cys-203, we wanted to examine whether mutation of Cys-203 to a serine would block GSNO-mediated protection or modulate mPTP opening. Initially, we assessed mPTP opening induced by H2O2 in WT CypD MEFs transfected with control plasmids or CypD−/− MEFs transfected with WT CypD using the calcein AM-cobalt chloride quenching method (Fig. 2A). In this technique, calcein/acetoxy-methyl ester enters the cell (cytosol and mitochondria) and becomes fluorescent upon de-esterification. Co-loading of cells with cobalt chloride quenches the fluorescence in the cytosol but not in the mitochondria since cobalt is not transported across the mitochondrial membranes. H2O2 is used as it is a known inducer of mPTP opening (3). As mPTP is induced, mitochondrial calcein fluorescence is quenched by cobalt. Treatment of WT MEFs with H2O2 for 10 min induced a 46 ± 4.4% quenching of calcein fluorescence consistent with mPTP opening in 46% of the mitochondria (Fig. 2A). CypD−/− MEFs that were reconstituted with WT CypD showed similar induction of mPTP as WT MEFs. Furthermore, as expected, H2O2 treatment of CypD−/− MEFs resulted in a much reduced quenching of calcein fluorescence consistent with resistance to mPTP opening in the absence of CypD. As NO can decrease mPTP opening (28–32) and also leads to SNO of CypD (32), we reasoned that GSNO treatment might inhibit activation of mPTP. To test this hypothesis, WT MEFs and CypD−/− MEFs transfected with either an empty vector or with WT CypD were treated with an NO donor, GSNO, for 15 min prior to H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2A). Treatment with 1 mm GSNO significantly attenuated H2O2-induced mPTP opening by 29 ± 2.6% in WT MEFs (n = 5, p < 0.05). GSNO treatment similarly attenuated H2O2-induced mPTP opening in MEFs transfected with WT CypD. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that SNO of CypD is important in cytoprotection. As expected, GSNO treatment did not provide any additional protection in CypD−/− MEFs treated with H2O2 (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

H2O2-induced mPTP opening is blocked by GSNO. In A, CypD WT MEFs were transfected with pCMV-XL6 (control (Con) plasmids). CypD−/− MEFs (KO) were transfected either with pCMV-XL6 (control plasmids) or WT CypD for 48 h as labeled in each panel. After transfections, mPTP opening was assessed using H2O2 in the presence and absence of a NO donor, GSNO, using the calcein-cobalt quenching technique. *, p < 0.05 versus WT+empty or KO+CypD (n = 5). In B, PPIase activity was measured using recombinant CypD in the presence of 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 mm GSNO. The reaction was initiated with PPIase substrate and chymotrypsin as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The kobs for PPIase activity was calculated using non-linear regression analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The k0 is the PPIase activity in the absence of CypD (the non-enzymatic rate) was also calculated using non-linear regression and was subtracted from the kobs. The results represent average measurements from three independent assays.

We next wanted to determine whether GSNO would alter PPIase activity of CypD. We measured PPIase activity of recombinant CypD in the presence of GSNO (Fig. 2B). GSNO has no effect on PPIase activity although the PPIase activity was sensitive to CsA (Fig. 2B).

Cys-203 of CypD Is Required for mPTP Opening

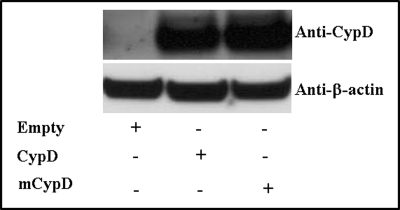

We next wanted to investigate whether Cys-203 of CypD is necessary for inhibition of mPTP with GSNO treatment. Protein SNO has been shown to play an important role in cytoprotection (22–26, 33). Previously, Kohr et al. (34) found CypD is SNO on cysteine 203 (KIVITDC*GQLS) after GSNO treatment. We also found (Fig. 1) that CypD is SNO at Cys-203 in preconditioned Langendorff-perfused hearts. We hypothesized that SNO of Cys-203 in CypD might alter its ability to activate mPTP opening. To assess the role of SNO on CypD, we mutated Cys-203 of CypD to a serine residue (C203S) using site-directed mutagenesis. We then confirmed the mutation by restriction digestion (Fig. 3A) and by DNA sequencing (Fig. 3B). We next expressed C203S-CypD in CypD null (CypD−/−) MEFs. We isolated primary CypD−/− MEFs and transfected them with either the WT CypD or mutated C203S-CypD for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 4, similar levels of C203S-CypD and WT CypD were expressed in the CypD−/− MEFs.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of mutated C203S-CypD in CypD−/− MEFs. CypD−/− MEFs (KO) were transfected with pCMV-XL6 (control plasmids), WT CypD, or mutated C203S-CypD plasmids for 48 h. After 48 h of transfection, proteins were extracted, and samples were analyzed by Western blot analysis using anti-CypD or anti-β-actin (as a loading control). Representative autoradiographs are shown (n = 4). mCypD, mutant CypD.

We next examined the ability of C203S-CypD to regulate the mPTP (Fig. 5). If our hypothesis is correct, we would expect that C203S-CypD should behave as WT CypD MEFs in the absence of GSNO, but C203S-CypD should not allow protection by GSNO treatment. We pretreated CypD−/− MEFs transfected with either mutated C203S-CypD (mCypD) or WT CypD with GSNO followed by H2O2 addition. Unexpectedly, we found that MEFs expressing mutated C203S-CypD showed a reduced susceptibility to mPTP opening in the absence of GSNO and that GSNO treatment had no additional effect. Mutation of Cys-203 to a serine inhibited mPTP to the same extent as was observed in the CypD null MEFs. Quenching of calcein was similar in the presence (23%) and absence of GSNO (19%) (Fig. 5A); thus, GSNO provides no additional protection to mCypD−/− MEFs. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5B, consistent with data in the literature, the mPTP opening of MEFs transfected with WT CypD is blocked by CsA, a known mPTP inhibitor. However, addition of CsA to MEFs transfected with C203S CypD provided no additional protection from H2O2-induced mPTP opening (Fig. 5B).

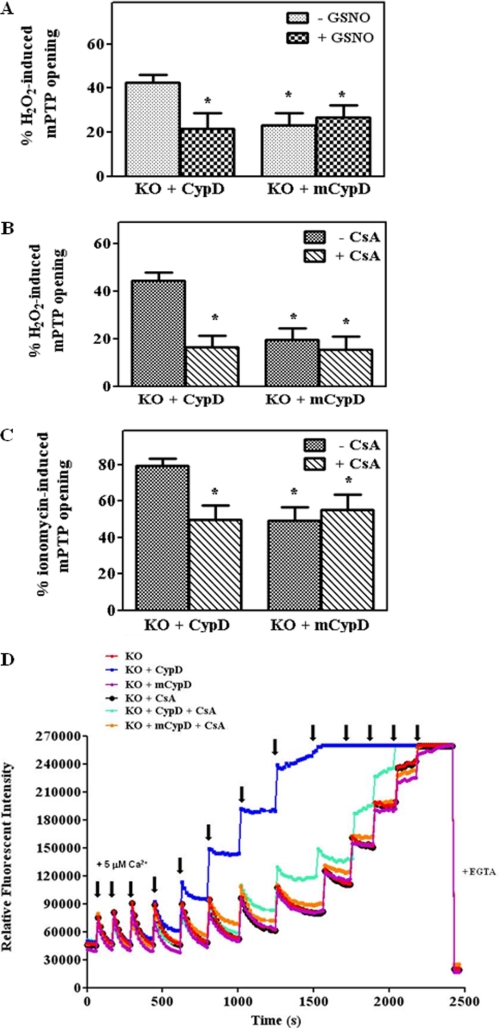

FIGURE 5.

mPTP opening is blocked by C203S-CypD. CypD−/− MEFs (KO) were transfected either with WT CypD or C203S-CypD plasmids for 48 h as labeled in each panel. After transfections, mPTP opening was assessed using H2O2 (A and B) or ionomycin (C) in the presence and absence of an NO donor, GSNO, or CsA using the calcein-cobalt quenching technique. In D, after transfections, CRC was measured using calcium-sensitive probe calcium green-5N in the presence of 5 μm Ca2+ pulses. A representative figure is shown from three independent assays. *, p < 0.05 versus WT+empty or KO+CypD (n = 5). mCypD, mutant CypD.

We next investigated whether C203S-CypD would protect MEFs against another mPTP inducer ionomycin, a Ca2+ ionophore. MEFs expressing WT CypD or C203S-CypD were assessed for mPTP opening in the presence of ionomycin. As shown in Fig. 5C, ionomycin induced a robust mPTP opening. After ionomycin treatment, MEFs expressing WT CypD exhibited a 79 ± 4.2% quenching of calcein fluorescence as compared with 49 ± 7.4% in MEFs expressing C203S-CypD (Fig. 5C). The mPTP opening in MEFs expressing WT CypD is sensitive to CsA. However, addition of CsA to MEFs expressing C203S CypD resulted in no further inhibition of mPTP. In addition to the calcein AM-cobalt chloride quenching method, we measured mPTP opening with the CRC assay using the calcium sensitive probe calcium green-5N (Fig. 5D). Consistent with the H2O2 and ionomycin-induced mPTP results, we found that CypD−/− MEFs or CypD−/− MEFs expressing the mutated CypD can sequester more calcium than MEFs expressing WT CypD (Fig. 5D, red or purple versus blue lines). The mPTP opening is sensitive to CsA in the group of KO MEFs transfected with WT CypD (turquoise versus blue line), but CsA has no additional inhibition on Ca2+ uptake in KO MEFs transfected with the mutated CypD (orange versus purple line). Taken altogether, these data indicate a critical role of Cys-203 in CypD and suggest that Cys-203 is necessary for CypD to facilitate mPTP opening.

C203S-CypD Reduces H2O2-induced Cell Death

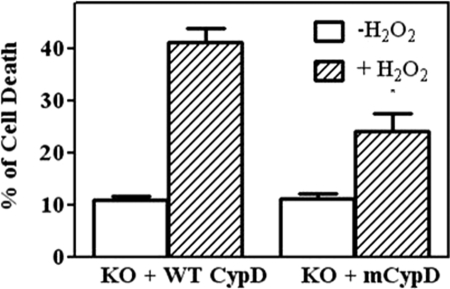

To determine whether C203S-CypD would protect MEFs from H2O2-induced cell death, MEFs expressing WT CypD or C203S-CypD were treated with H2O2 for 6 h to induce cell death. After treatment, we determined the percent of cell death using the LIVE/DEAD viability kit. MEFs expressing C203S-CypD showed reduced cell death as compared with MEFs expressing WT CypD (24 ± 3.5% versus 41 ± 2.7%, Fig. 6). Our results indicate the importance of cysteine 203 in modulating mPTP opening in response to oxidative stress-induced cell death.

FIGURE 6.

C203S-CypD reduces H2O2-induced cell death. CypD−/− MEFs (KO) were transfected with WT CypD or mutated C203S-CypD plasmids for 48 h. After transfections, MEFs were treated with 1 mm H2O2 for 6 h to induce cell death. Cell death was assessed using the LIVE/DEAD viability kit (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The results represent average measurements from three independent assays. mCypD, mutant CypD. *, p < 0.05, versus KO + WT CypD in the presence of H2O2.

In Vivo Expression of WT CypD and Mutated C203S-CypD in CypD−/− Mouse Liver

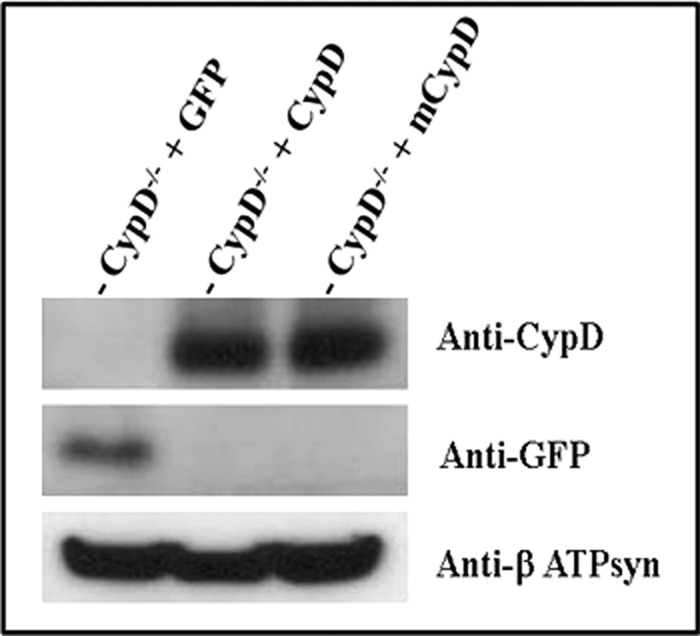

As we showed the importance of Cys-203 of CypD in MEFs, we next wanted to express the mutated C203S-CypD in vivo and determine its effect on mPTP opening. We first generated adenovirus vectors encoding WT CypD or mutated C203S-CypD and injected viral particles into CypD−/− mice via tail vein at 5.6 × 107 pfu/g mouse. Seventy-two hours after injection, we extracted the liver tissue and determined the expression of CypD (Fig. 7). Adenovirus-mediated transfer of CypD and mutated C203S-CypD resulted in similar levels of expression in liver tissue (Fig. 7). As a control, we injected CypD−/− mice with an adenovirus harboring a gene encoding GFP to determine infection efficiency and to ensure the lack of virus related effects. As expected, proteins extracted from CypD−/− mice have no expression of CypD but only express GFP. Our results confirmed similar expression of WT CypD and mutated C203S-CypD in liver tissue.

FIGURE 7.

Induction of mutated C203S-CypD expression in the liver mitochondria of CypD−/− mice abolished Ca2+-induced mPTP opening. Liver samples were obtained 72 h after adenovirus injections with an adenoviral vector driving WT CypD, mutated C203S-CypD, or AdCMV-GFP (used as a control) expressions. Immunoblot analysis of 40 μg of mitochondrial protein extracted from mouse livers, and the resulting blots were probed with anti-CypD, GFP, and β-ATP synthase (ATPsyn) antibodies. Representative blots are shown (n = 6). mCypD, mutant CypD.

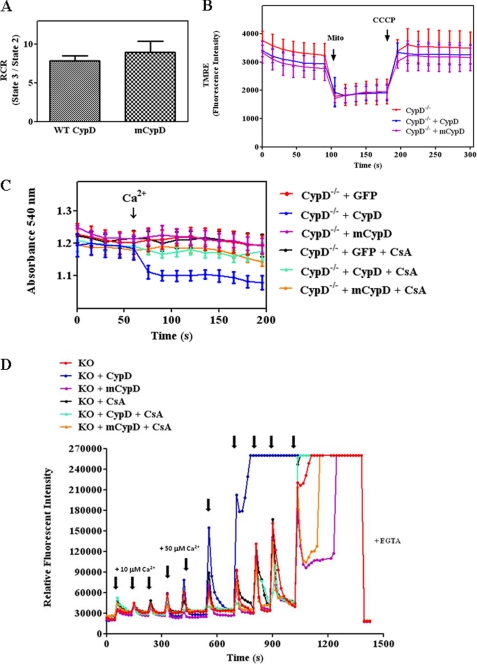

We next investigated whether C203S-CypD would alter oxygen consumption or membrane potential. Respiratory control ratio was measured as the ratio between mitochondrial respiration states 3 and 2. Isolated mitochondria expressing WT CypD or mutated CypD exhibited similar respiratory control ratio (state 3/state 2) (Fig. 8A). We measured membrane potential using the fluorescent probe TMRE. There was no difference in maximal membrane potential or dissipated membrane potential (carbonyl cyanide p-chlorophenylhydrazone treatment) (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

C203S-CypD expression in the liver mitochondria of CypD−/− mice does not alter mitochondrial oxygen consumption and membrane potential. Liver mitochondrial samples were obtained as described in Fig. 7. Respiratory control ratio (RCR) (A) was determined using glutamate and malate as substrates by calculating state 3/state 2 using a Oxygraph electrode. In B, membrane potential was monitored using the fluorescent dye TMRE in coupled respiring mitochondria and then in the presence of 1 μm protonophore carbonyl cyanide p-chlorophenylhydrazone. In C, mitochondrial swelling assay was measured by absolute absorbance at baseline and after Ca2+ (250 μm) addition in the presence and absence of CsA in isolated liver mitochondria from each of the indicated groups as described in A. The data show the profile of absorbance at 540 nm of mitochondrial suspensions after exposure to 250 μm CaCl2. The results represent average measurements from four independent preparations of liver mitochondria from separate mice. In D, CRC was measured using the calcium-sensitive probe calcium green-5N in the presence of 10 μm and 50 μm Ca2+ pulses. mCypD, mutant CypD.

To determine whether mutated CypD altered the response to mPTP opening, liver mitochondria isolated from CypD−/− mice, CypD−/− mice infected with WT CypD, or CypD−/− mice infected with mutated C203S-CypD were assessed for their ability to undergo Ca2+-induced swelling (Fig. 8C). As expected, mitochondria isolated from CypD−/− mice exhibited resistance to swelling after addition of Ca2+, which is consistent with previous data showing that CypD regulates mPTP opening (3). Mitochondria isolated from livers of CypD−/− mice reconstituted with WT CypD underwent mPTP opening as indicated by Ca2+-induced swelling, which results in a decrease in absorbance at 540 nm (Fig. 8C, blue line). This effect was sensitive to CsA (turquoise line). In contrast, mitochondria isolated from livers of CypD−/− mice with mutated C203S-CypD (purple line) exhibited similar mPTP opening as the mitochondria isolated from CypD-KO mice (red line), and mPTP opening in the mitochondria expressing mutated CypD showed no additional inhibition with CsA (orange line). In addition, we have measured mPTP opening using the CRC assay as in Fig. 5D. Consistent with the swelling assay (Fig. 8C), we found that liver mitochondria isolated from CypD−/− mice with mutated C203S-CypD can sequester more calcium than mitochondria isolated from CypD−/− mice expressing WT CypD (Fig. 8D, purple versus blue traces). Furthermore, CsA has no additional effect on Ca2+ uptake in CypD−/− mice with mutated C203S-CypD (orange trace). Taken together, these results indicate that Cys-203 of CypD is required for mPTP opening.

DISCUSSION

CypD is currently the only defined element of the mPTP. In this study, we show that CypD activation of the mPTP is critically dependent on Cys-203. Mutation of Cys-203 to a serine impairs CypD activation of mPTP such that mutated C203S-CypD results in a similar reduction in mPTP opening as total loss of CypD. Consistent with previous studies, CypD−/− cells exhibit reduced susceptibility to mPTP opening with calcium overload or oxidative stress (3). In this study, we show that mutation of Cys-203 results in a CypD that is unable to activate mPTP (Figs. 5 and 8, C and D) and improves cell viability (Fig. 6); however, this mutation has no effects on mitochondrial bioenergetics (Fig. 8, A and B). These data suggest that Cys-203 is necessary for CypD to activate the mPTP. A previous study identified Cys-203 of CypD as a redox-sensitive residue (13). The inability of C203S-CypD to activate the mPTP is not due to complete loss of structure as Linard et al. (13) showed that C203S-CypD did not impair isomerase activity. CypD catalyzes a peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerization (PPIase). Linard et al. (13) showed that PPIase activity of WT CypD is reduced by 20% if CypD is oxidized, whereas PPIase activity of C203S-CypD is unaffected by oxidation.

SNO has been reported to reduce cell death in the setting of I/R injury (22–24, 33). Nitric oxide at low levels has also been shown to reduce mPTP opening, although high levels of nitric oxide can stimulate mPTP (30–32). Activation of the mPTP is generally thought to be the primary mediator of cell death in I/R injury. Taken together, this would suggest that SNO might reduce cell death by directly or indirectly inhibiting the mPTP. It was therefore of interest that CypD is SNO following cardioprotection with ischemic preconditioning (Fig. 1). We also have shown previously that GSNO can SNO Cys-203 of CypD (34). Our data showed that GSNO reduces mPTP opening with WT CypD (Fig. 2A); however GSNO has no effects on PPIase activity using recombinant CypD (Fig. 2B). However, we do not know the percentage of CypD that is SNO with GSNO addition, and it is possible that the percentage is too small to have an effect on isomerase activity. However, the lack of effect of GSNO on isomerase activity is consistent with data in the literature showing mutation of Cys-203 does not inhibit PPIase activity (13). Nevertheless, mutation of Cys-203 inhibits mPTP opening to a similar extent as total loss of CypD. These data suggest a critical role of Cys-203 in the activation of mPTP. In addition, these data also support the hypothesis that CypD is a target of SNO and that SNO of Cys-203 acts similar to mutation of Cys-203 or to CypD deletion. It is possible that a free SH group is important to form a disulfide bond perhaps involved in targeting CypD to the pore. Mutation of Cys-203 or SNO of this cysteine could alter protein-protein interactions between CypD and mPTP component(s). Alternatively, oxidation of this Cys-203 could be an important factor in mPTP activation, and oxidation would be blocked by SNO or mutation of this site. Previous studies by Kohr et al. (34) suggest that Cys-203 of CypD is oxidized during I/R and to a lesser extent in preconditioning, a known cardioprotective phenomena. It has been suggested that cysteine residues which are SNO are shielded from further oxidative damage (23, 33). Further studies are necessary to elucidate the role(s) of Cys-203 of CypD in modulating I/R injury.

In summary, the Cys-203 residue of CypD is a critical residue for SNO and mPTP activation. Mutation of Cys-203 to a serine impairs CypD activation of mPTP similar to CypD ablation. Further investigation of the role of this cysteine residue may provide a better understanding of the molecular identity of the mPTP and the mechanistic basis for mPTP opening as well as how cytoprotective interventions inhibit mPTP opening for protection from I/R injury. Taken together, these data provide a novel regulatory role for cysteine 203 of CypD in mPTP regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffery Molkentin (University of Cincinnati) for the CypD+/+ and CypD−/− mice. We also thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility, the Laboratory of Animal Medicine and Surgery, the NHLBI Proteomics Core Facility for assistance with the flow cytometry calcein-cobalt assay, tail vein injections of viral particles, and mass spectrometry analyses, respectively.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants Z01HL006059 and Z01HL002066 (to T. T. N. and E. M.), 1F32HL096142 (to M. K.) and 5R01HL039752 (to C. S.).

- mPTP

- mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- CypD

- cyclophilin D

- I/R

- ischemia/reperfusion

- GSNO

- S-nitrosoglutathione

- SNO

- S-nitrosylation

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PPIase

- peptidylprolyl isomerase

- AM

- acetoxymethyl ester

- CsA

- cyclosporine A

- CRC

- calcium retention capacity.

REFERENCES

- 1. Griffiths E. J., Halestrap A. P. (1993) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 25, 1461–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petronilli V., Penzo D., Scorrano L., Bernardi P., Di Lisa F. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12030–12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baines C. P., Kaiser R. A., Purcell N. H., Blair N. S., Osinska H., Hambleton M. A., Brunskill E. W., Sayen M. R., Gottlieb R. A., Dorn G. W., Robbins J., Molkentin J. D. (2005) Nature 434, 658–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baines C. P. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H903–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matsumoto S., Friberg H., Ferrand-Drake M., Wieloch T. (1999) J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 19, 736–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldkamp T., Kribben A., Weinberg J. M. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 288, F1092–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Devalaraja-Narashimha K., Diener A. M., Padanilam B. J. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 297, F749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morin D., Pires F., Plin C., Tillement J. P. (2004) Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 2065–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bernardi P., Petronilli V. (1996) J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 28, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Halestrap A. P. (2009) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 46, 821–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crompton M. (1999) Biochem. J. 341, 233–249 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chernyak B. V. (1997) Biosci. Rep. 17, 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linard D., Kandlbinder A., Degand H., Morsomme P., Dietz K. J., Knoops B. (2009) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 491, 39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kowaltowski A. J., Castilho R. F., Vercesi A. E. (1996) FEBS Lett. 378, 150–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petronilli V., Costantini P., Scorrano L., Colonna R., Passamonti S., Bernardi P. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 16638–16642 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halestrap A. P., Woodfield K. Y., Connern C. P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3346–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McStay G. P., Clarke S. J., Halestrap A. P. (2002) Biochem. J. 367, 541–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cruz T. S., Faria P. A., Santana D. P., Ferreira J. C., Oliveira V., Nascimento O. R., Cerchiaro G., Curti C., Nantes I. L., Rodrigues T. (2010) Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 1284–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costantini P., Chernyak B. V., Petronilli V., Bernardi P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 6746–6751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salet C., Moreno G., Ricchelli F., Bernardi P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21938–21943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakagawa T., Shimizu S., Watanabe T., Yamaguchi O., Otsu K., Yamagata H., Inohara H., Kubo T., Tsujimoto Y. (2005) Nature 434, 652–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun J., Murphy E. (2010) Circ. Res. 106, 285–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun J., Steenbergen C., Murphy E. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1693–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin J., Steenbergen C., Murphy E., Sun J. (2009) Circulation. 120, 245–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun J., Morgan M., Shen R. F., Steenbergen C., Murphy E. (2007) Circ. Res. 101, 1155–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shiva S., Sack M. N., Greer J. J., Duranski M., Ringwood L. A., Burwell L., Wang X., MacArthur P. H., Shoja A., Raghavachari N., Calvert J. W., Brookes P. S., Lefer D. J., Gladwin M. T. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 2089–2102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burwell L. S., Nadtochiy S. M., Tompkins A. J., Young S., Brookes P. S. (2006) Biochem. J. 394, 627–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maejima Y., Adachi S., Morikawa K., Ito H., Isobe M. (2005) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 38, 163–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Atar S., Ye Y., Lin Y., Freeberg S. Y., Nishi S. P., Rosanio S., Huang M. H., Uretsky B. F., Perez-Polo J. R., Birnbaum Y. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290, H1960–1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brookes P. S., Salinas E. P., Darley-Usmar K., Eiserich J. P., Freeman B. A., Darley-Usmar V. M., Anderson P. G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20474–20479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pagliaro P., Moro F., Tullio F., Perrelli M. G., Penna C. (2011) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 833–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burwell L. S., Brookes P. S. (2008) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 579–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kohr M. J., Sun J., Aponte A., Wang G., Gucek M., Murphy E., Steenbergen C. (2011) Circ. Res. 108, 418–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohr M. J., Aponte A. M., Sun J., Wang G., Murphy E., Gucek M., Steenbergen C. (2011) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H1327–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]