Abstract

This study examines whether levels of father engagement (e.g., verbal stimulation, caregiving, and physical play) vary by race/ethnicity using a model that controls for fathers’ human capital, mental health, and family relationships. It also tests whether the models work similarly across race/ethnic groups. Its sample of N=5,089 infants and their families is drawn from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). We found that, after including controls, African American and Latino fathers had higher levels of engagement in caregiving and physical play activities than White fathers. There were no differences in verbal stimulation activities across race/ethnicity. Fathers’ education (college level) predicted more verbally stimulating activities whereas fathers’ report of couple conflict predicted less caregiving and physical play. Although levels of engagement differed across the groups, the overall models did not differ by race/ethnicity, except for physical play. African American mothers who reported high levels of depressive symptoms had partners who engaged in more physical play than White mothers with high levels of depressive symptoms.

Keywords: father engagement, infancy, race/ethnicity

One-fifth of American children are of minority background (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2009) and a high proportion of these children are infants. Yet, this diversity is not represented in studies of parenting. The parenting literature is dominated by research on mother-child interactions in majority two-parent White families. Although mothers and fathers still differ in the amount of time they spend with their children, fathers’ involvement with their children has increased over the last three decades (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). However, the extant literature has more frequently focused on older children than on infants (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000). Thus, it is difficult to discern whether fathers engage with infants similarly to the ways they engage with older children. Finally, there is an increased awareness in the field that more studies need to be conducted on parenting of infants by minority fathers (Cabrera & Garcia-Coll, 2004; Campos, 2008; Coley, 2001; Gavin et al., 2002). The present study attempts to correct these omissions.

Developmental perspectives posit that parental behavior during the first few years of life is critical for optimal development (Edwards, Sheridan, & Koche, 2010). To develop and thrive, infants require consistent and high-quality parental investment. Parents’ and other caregivers’ engagement in caregiving (e.g., changing diapers), physical play (e.g., playing peek-a-boo, tickling), and cognitively stimulating activities (e.g., reading to child, singing songs) is critical for infants’ developing attachment, communication, and social cognition (Hart & Risley, 1995, 1999; Risley & Hart, 2006). Thus, infancy is a time in which fathers might uniquely influence their children’s rapidly developing social, cognitive, and language skills, influences that last beyond the earliest years (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000; Snow, Porche, Tabors, & Harris, 2007). When fathers engage with their children in ways that support their healthy development, they also increase their own enjoyment of and commitment to their infants, which can lead to long-term involvement (Cabrera, Fagan, & Farrie, 2008; Lamb, 2004; Lamb & Lewis, 2004). Although recent trends suggest increased overall father involvement, variation in fathering behaviors has also been noted, some fathers being more committed and engaged than others (Bianchi et al., 2006; Lerman, 1993; Perloff & Buckner, 1996; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Research suggests that father engagement varies by fathers’ biological relationship to the child, human capital, psychological well being (e.g., depression), and sources of social support and stress (e.g., marital quality) (Belsky, 1984; Hossain & Roopnarine, 1994; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004; Toth & Xu, 1999). Given that infancy represents a critical opportunity to support and encourage men in their new roles as fathers, it is important to understand how fathers engage with their children during infancy and the factors that predict variation in levels of engagement. Moreover, as minority families become an increasingly larger part of American society, it is critical to understand how race/ethnicity is linked to differential levels or types of father engagement.

In this study, we use the Early Childhood Longitudinal-Birth Cohort data (ECLS-B), a nationally representative sample of infants and their fathers. We address the gaps in the literature by, first, describing levels of father engagement with infants and, then, testing a model of the predictors of father engagement for African American, Latino, and White fathers. More specifically, this study is framed by the following research questions: (1) In a model of father engagement that includes fathers’ human capital, mental health, and family relationships, does race/ethnicity predict different levels of involvement? And (2) Are models similar across race/ethnic groups? This study contributes to the literature in three ways: (1) it compares a model of father involvement across three race/ethnic groups; (2) it tests Belsky’s (1984) model of parenting with Latino fathers; and, (3) it uses nationally representative data.

Father Engagement in Infancy

The research on father engagement distinguishes between engagement in caregiving activities and engagement in play, leisure, or affiliative activities with the child because these types of involvement have different correlates and consequences (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). In detailed time studies, these activities occupy the majority of fathers’ time (Yeung, Sandberg, Davis-Kean, & Hofferth, 2001). From the developmental and parenting literatures, parent engagement in caregiving, physical play, and in activities such as reading and singing songs that stimulate children’s cognitive development is critical for children’s development (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; De Wolff & Van Ijzendoorn, 1997; Hart & Risley, 1995, 1999; Risley & Hart, 2006). Research shows that babies pay attention to human voices and nonverbal communication, coo and babble, and build relationships through responsive interactions with their caregivers (Risley & Hart, 2006). Thus caregivers, including fathers, who engage with their infants in verbally stimulating ways, are more likely to promote and facilitate cognitive development in their children than those who do not (Bruner, 1981; Hart & Risley, 1995; Hoff, 2006; Nelson, 1996; Pancsofar & Vernon-Feagans, 2006; Vygotsky, 1978). More importantly, parents who read to their children as infants are more likely to read to their children during childhood (Bardige & Bardige, 2008). Two recent studies suggest that early father-infant engagement in various activities, including taking care of baby’s basic needs, engaging in play and reading or telling stories, is not only associated with later father involvement and promotes cognitive development, but it may also reduce the likelihood of infant cognitive delay (Bronte-Tinkew, Carrano, Horowitz, & Kinukawa, 2008; Cabrera et al., 2008; Pancsofar & Vernon-Feagans, 2010).

Comparisons across racial and ethnic groups of fathers have revealed a few differences in the level of father engagement mainly with older children (Yeung et al., 2001). Cultural models of parenting and socialization practices suggest that Latino values of familism (e.g., family obligations, family reciprocity) are linked to behaviors that encourage the fulfillment of family roles, such as taking care of children, and are thus related to high levels of father engagement (Buriel, 1993; Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002; Grau, Azmitia, & Quattlebaum, 2009; Landale & Oropesa, 2001). Evidence suggests that Latino fathers in the U.S. are generally warm and nurturing, and spend more time with their children in shared and caregiving activities than White fathers (Mirande, 1991, 1997; Roopnarine & Ahmeduzzaman, 1993; Toth & Xu, 1999). One study of 3-to-12- year-olds and their parents found that Latino fathers spent more time in caregiving activities than fathers from other ethnic groups (Hofferth, 2003).

High levels of father engagement have also been reported for African American fathers. Studies of young children show that levels of involvement in primary caregiving (e.g., feeding, and bathing) by African American fathers in middle- and lower-income two-parent families with infants and preschool children exceeded those reported for fathers from other ethnic groups (Ahmeduzzaman & Roopnarine, 1992; Hossain & Roopnarine, 1994; Roopnarine & Ahmeduzzaman, 1993). Other studies show that African American fathers engaged with their infants in physical play and are as likely as White fathers to spend time playing with them (Fagan, 1996; Roopnarine & Ahmeduzzaman, 1994). These studies are based on convenience samples and have limited generalizability. To our knowledge, there is no research using national samples of American children on whether levels of physical play vary across fathers by race/ethnicity.

Based on this review, we find that there are similarities and differences in levels of father engagement types across racial and ethnic groups. Minority fathers engage in caregiving activities with higher frequencies than White fathers. Although researchers have found some cross-cultural differences in terms of physical play (Edwards, 2000), and there are a couple of small-scale studies using samples from the United States, to our knowledge none have used national samples to explore how fathers are engaged with their infants across racial and ethnic groups. In terms of engaging in verbally stimulating activities with infants, there is little research with fathers and none comparing father engagement in this type of activity across race/ethnic groups.

Theoretical Framework

In this study, we use Belsky’s (1984) process model of parenting because it has been extensively tested, mainly with mothers, and has shown that parenting is best explained by the joint contributions of parents and children as well as the context in which these relationships unfold. It includes multiple factors identified by research as important predictors of father engagement, including parent’s mental health and family relationships (Fagan, 1998; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004). Moreover, this model has clear implications for programs and policy. Parents’ mental health and family relationships, for example, can be targeted for intervention. Although this model has also been used to explain variation among African-American mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors (Bluestone & Tamis-LeMonda, 1999), it has rarely been used with Latino families, with one exception (Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006). Cabrera and colleagues, using data from the ECLS-B, found that Latino fathers’ report of happiness with their partner was most consistently linked to fathers’ engagement with their children.

According to Belsky’s (1984) parenting process model, parenting that leads to optimal development is directly influenced by interacting systems that operate at different levels over the life course and include parents’ psychological functioning (e.g., depressive symptoms), child’s characteristics (e.g., child age), and contextual sources of stress and support (e.g., marital quality). For example, compared to nondepressed parents, depressed parents are more likely to use harsh discipline and display hostility toward their children, which can directly compromise development (Downey & Coyne, 1990). Findings also show that negativity and conflict between parents is a source of stress that is likely to influence their parenting behaviors (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Thus, it is expected that parents with high depressive symptoms and more reported conflict in their relationships with their partners would also exhibit more negative parenting than their counterparts.

In addition to mental health and family relationship quality, fathering behaviors have also been linked to fathers’ human capital. Resource theory stipulates that parents with greater human capital (e.g., education, employment) will invest more money and time in their children and engage in more learning and verbally stimulating activities with them than those with less such capital (Edwards et al., 2010; Guo & Harris, 2000; Haveman & Wolfe, 1994; McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000). In Belsky’s (1984) model, human capital can be conceptualized as a father’s personal characteristic, which can directly influence fathering behaviors (Wood & Repetti, 2004). One way in which this can happen is that fathers with higher levels of education are better able to provide for their children, which may lead to increased involvement (spending time with them) than fathers who cannot fulfill this role (McLanahan, 2009). Because White parents have, on average, higher levels of education, White children are likely to have access to more social and economic resources than minority children (Huang, Mincy, & Garfinkel, 2005). Thus, it is expected that lower educational levels among racial and ethnic minority fathers might contribute to lower levels of engagement, specifically in activities that promote cognitive development. If differential resources across groups are the reason for differential engagement, then racial and ethnic differences will disappear or be highly reduced once we control for fathers’ education. Thus, fathers’ years of education can explain variation in levels of father engagement both across and within racial and ethnic groups. It is also possible that fathers’ work hours may constrain fathers’ ability to be involved with their children (Brayfield, 1995). That is, fathers who spend greater time at work might have less time to spend with their children. Because one cannot identify all ways in which ethnic and racial groups are different, there may still be some group differences. In summary, using Belsky’s (1984) model, we expect levels of father engagement to differ across groups; however, we do not expect any racial and ethnic differences in the set of factors that predict father engagement.

Conceptual Model

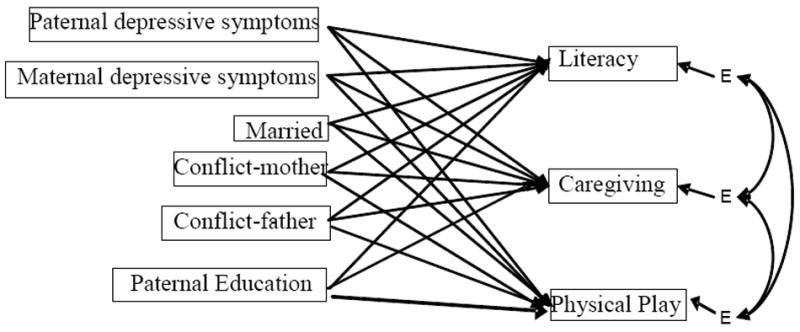

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model based on Belsky’s (1984) parenting model. Fathers’ depressive symptoms are hypothesized to have a direct effect on father engagement (e.g., singing songs, reading, bathing). In White European samples, maternal or paternal depression has been shown to be associated with more marital problems and higher levels of hostile or negative parenting such as insensitivity to infants’ cues and inadequate stimulation (Conger et al., 1992; Cummings et al., 2000; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Parke et al., 2004). However, few studies have examined whether depressive symptoms have similar influences on fathering behavior in Latino and African American families. Using data from the ECLS-B, one study demonstrates that paternal depressive symptoms, but not maternal depressive symptoms, predict fewer caregiving activities by fathers in a national sample of Mexican American infants and their fathers, after controlling for socioeconomic status (Cabrera et al., 2006). Based on this review, we expect that minority fathers who are depressed would be less engaged with their children than those who are not. There is some evidence that fathers are sensitive to mothers’ risk, including depression (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Raymond, 2004; Doherty, Kouneski, & Erickson, 1998). Thus we expect that maternal depression will be related to father engagement.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

According to our model, marital status is hypothesized to be an important determinant of fathers’ type and level of engagement with his children. This is particularly relevant for minority families because African American children are more likely than other children to be born into single-mother households (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Compared to nonresident fathers, fathers who reside with their families are more involved with their children because they have more access to them on a daily basis (Cabrera, Ryan, Jolley, Shannon, & Tamis-Lemonda, 2008). For similar reasons, residential fathers are also more likely to engage in sensitive behaviors with their children than nonresidential fathers (Brophy-Herb, Gibbons, Omar, & Schiffman, 1999). Fathers who are married are more likely to be involved with their children than fathers who are cohabiting, although the evidence here is mixed (Hofferth & Anderson 2003; Laughlin, Farrie, & Fagan, 2009).

Our model also hypothesizes that conflict between parents, a source of stress, can undermine parenting (Allen & Hawkins, 1999; Fagan & Barnett, 2003). The evidence on the effects of marital conflict on fathering is mixed. Some studies of African American and White fathers have found that greater paternal involvement was more likely to occur when fathers established warm and close relationships with their children’s mother (Cochran, 1997; Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1999; Danziger & Radin, 1990; Florsheim et al., 1997; Lamb & Elster, 1985). Other findings based on White and African American families have shown that hostility between parents can reduce father engagement with their children but not mother engagement with their children (McKenry, Price, Fine, & Serovich, 1992), perhaps because fathers are more susceptible to partner influence than are mothers (Belsky, Rovine, & Fish, 1989; Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley, & Roggman, 2007). A more recent study that uses the ECLS-B data, however, finds no association between parent-reported conflict and Mexican American fathers’ reports of engagement with their infants (Cabrera et al., 2006). The inconsistent findings might be accounted for by differences in how partner conflict is measured across studies and the fact that most studies only include conflict reported by one parent. In this study, we ask both parents to report on the frequency of arguments.

Fathers, who are better educated (have more human capital), are hypothesized to be more involved with their children than fathers who are not (Haveman & Wolfe, 1994). Highly educated fathers may have stronger beliefs about involvement or may be more able to be involved because they have higher earnings and more financial stability. There is some support for this notion. Studies show that more educated fathers show higher involvement in achievement-related activities than less-educated fathers, after controlling for hours spent at work (Hofferth & Anderson, 2003; Yeung et al., 2001).

Based upon our review, we expect that race/ethnic differences in verbal stimulation, physical play, and caregiving will be significant but small, once other variables are controlled. There is little reason to expect ethnic group differences in these patterns of relationships. Nonetheless, we allowed associations to vary across ethnic groups, conducting appropriate between-group comparisons of the overall models.

Method

Participants

To address our research questions, we used the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), the first study to follow a nationally representative cohort from birth through the early school years. The ECLS–B collected data on mothers, fathers, and children using multiple methods (e.g., interviews, child assessments, videotaped interactions) and sought to identify factors that influence children’s development in multiple domains that are important to later school readiness. The ECLS–B is one of the few national U.S. studies to obtain information directly from fathers through self-report, thus providing an opportunity to examine levels of father engagement as well as the unique contributions they can make to children’s well-being.

The ECLS-B sample was designed to represent the nearly four million children born in the United States in 2001. The sample was selected using a clustered list frame approach and the sampling frame included registered births in the National Center for Health Statistics’ (NCHS) vital statistics system. Children were sampled by occurrence of birth within a set of primary sampling units defined by counties or county groups. The initial sample excluded children who had died or who had been adopted after the issuance of the birth certificate and infants whose birth mothers were younger than 15 years at the time of their child’s birth (National Central for Education Statistics, 2005a).

This research used Wave 1. Analyses were conducted using questions about father engagement from the parent interview. In the first wave of data collection, a home visit was conducted with 10,688 primary caregivers. Fathers were recruited after mothers identified them. Three quarters (73%, n=6,938) of eligible resident fathers completed the self-administered questionnaire and half (50.9%, n=679) of eligible nonresident biological fathers completed the interviews. NCES created probability weights that were used to adjust for differential selection probabilities and nonresponse rates for the mother interview and father questionnaire (National Central for Education Statistics, 2005b). The sample for this study included 9-month-old infants (n=5,089) living with both biological parents in households with their African American (n=470), Latino (n=1,586), and White fathers (n=3,102). Children of “other” race/ethnic origins were deleted. Because we were only concerned with the race/ethnicity of the father, we did not exclude interracial couples, which represent a very small group in the ECLS-B. Weights were used to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and for differential response to the first interview.

To understand the selective nature of our analytical sample of infants with resident biological parents (i.e., married and cohabiting compared to infants residing in other family structures such as single parent, and non-biological married or cohabiting parents), we examined whether household income, mothers’ age, education, and mental health, and maternal report of couple quality differed by marital status. Married and cohabiting biological mothers had higher household incomes [t (9,038) = 38.79, p < 0.001], were older [t (8,926) = 33.48, p <0.001), and were more educated [t (7,810) = 3.32, p < 0.001] than were mothers from other family structures. They also reported fewer depressive symptoms [t (6,813) =16.36, p<0.001], more family support, and more happiness in their relationships with their partner [t (4,195) =7.59, p<0.001] than did those mothers who did not reside with their child’s biological father. The findings in this paper pertain to the population of children who live with both biological parents at 9 months of age. The data are representative of infants born in 2001 into two-parent families.

At 9 months, 57.49% of the full sample of ECLS-B infants’ resident fathers completed a questionnaire that asked about their involvement with their children. A nonresponse bias analysis that compared the characteristics of children, their mothers, and fathers using data from the birth certificate frame and from the ECLS-B mother interview showed few differences between responding and nonresponding fathers for the full ECLS-B sample. Moreover, the few differences found between these groups were corrected by adjustments to the sampling weights (Nord, Edwards, Andreassen, Green, & Wallner-Allen, 2006).

The final analytic sample for our study was n=5,089 infants (1,586 Latino, 3,102 White, and 401 African American) who lived with both biological parents, whose mothers completed a parent interview, whose fathers completed a resident father questionnaire, and who completed a cognitive assessment at approximately 9-months of age (see Table 1). All data were weighted using the ECLS-B custom longitudinal weights for analyses that utilize father information at 9 months (Nord et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Infant Age, Fathers’ Demographic Characteristics, Mother-Father Relationship, and Father Engagement in Two-Parent Families by Race and Ethnicity

| Variables | Total n = 5089 M(SD)/% |

African American n= 401 M(SD)/% |

Latino n= 1586 M(SD)/% |

White n = 3102 M(SD)/% |

ANOVA Statistics F-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Age (M) | 10.5(1.82) | 10.6(1.86) | 10.5(1.76) | 10.4(1.77) | |

| Parents’ Characteristics(Education and Mental Health) | |||||

| Father depressive symptoms | 1.31(0.4) | 1.4(0.51)*1 | 1.27(0.38) | 1.31(0.38)*2 | 16.7* |

| Father education | |||||

| Up to high school | 39.8% | 45.90% | 69.80% | 30.40% | 276* |

| Some college | 28.9% | 34.3% | 19.1% | 31% | 30* |

| College plus | 31.3% | 19.8% | 11.1% | 38.6% | 159* |

| Mother depressive symptoms | 1.38(0.41) | 1.44(0.48)*3 | 1.38(0.45) | 1.37(0.39) | 6.38* |

| Father working | 31.3(15.8) | 32.10(15) | 30.7(17.1) | 29.1(17.3) | 14.2* |

| Contextual Sources | |||||

| Married | 81.60% | 63.90% | 68.10% | 88% | 168* |

| Conflict - father report (1-3) | 1.78(.47) | 1.91(0.60)*4 | 1.79(0.56) | 1.87(.48) | 13.49* |

| Conflict -mother report | 1.77(.47) | 1.83(0.55)*5 | 1.55(0.50) | 1.77(0.44) | 5.93* |

| Father Engagement | |||||

| Verbal stimulating (4-pt.) | 2.32(0.73) | 2.35(0.73) | 2.32(0.72) | 2.32(0.73) | 0.3 |

| Caregiving (6-pt.) | 4.81(0.73) | 4.94(0.76)*6 | 4.79(0.78) | 4.79(0.71) | 16.3* |

| Physical Play (5-pt.) | 3.03(0.81) | 3.39(0.78)*7 | 3.3(0.83)*8 | 2.91(0.77) | 146* |

Note:

p<.01

African American fathers are more depressed than White and Latino fathers;

White more depressed than Latino fathers;

African American mothers more depressed than White and Latino mothers;

African American fathers report more conflict than White and Latino fathers;

African American mothers report more conflict than White mothers;

African American fathers engage in more caregiving than Latino and White fathers;

African American engage in more physical play than White fathers

Latino fathers engage in more physical play than White fathers

Procedure

The first wave of data was collected in 2001. During home visits, field staff conducted a computer-assisted interview with the children’s primary caregiver (99% of whom were the child’s biological mother), conducted assessments of children’s mental and motor development, took physical measures, and videotaped caregiver-child interactions. Each visit lasted 1 ½ to 2 hours. Resident fathers (biological or father figure) completed a 20-minute questionnaire. If the father was not at home during the visit, the questionnaire was left with the mother to give to her spouse/partner and mail back in a self-addressed stamped envelope.

Measures

Sociodemographic data

The birth certificate provided date of birth, which was used to calculate the infants’ ages at the time of the home visit. The father questionnaire asked fathers to report on family structure (1=married, 0=cohabiting), race/ethnicity (dummy variables for African American and for Latino, with White the omitted variable), and educational attainment, which was coded using three dummy variables (less than and up to high school, some college, and more than college, with up to high school omitted). We included education as a categorical variable because research has shown that certification such as getting a high school or college degree, not just number of years, is an important determinant of certain parenting behaviors. For example, parents with a high school diploma may act quite differently from those with just one fewer or one more year of schooling; this association is not linear (Cabrera et al., 2007; Entwisle & Astone, 1994). In our study, we collapsed the “less than high school” and “completed high school” into one category because of the small number of men who had not completed high school.

Depressive symptoms

Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale–Short Form (CESD-SF; Ross, Mirowsky, & Huber, 1983), which comprised 12 of the 20 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a self-report scale that measured the absence or presence of negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors during the prior week. Sample items include “How often in the past week did you … feel depressed? feel lonely?, have crying spells?, and have difficulty sleeping?” Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = rarely or never to 3 = most or all days). Mean scores were computed for cases with responses to at least 11 of 12 items. Higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. The scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency for this sample with a coefficient alpha of .88 for mothers and .87 for fathers.

Mother-father relationship quality

To rate the quality of parents’ relationships with their partners, both mothers and fathers were asked 10 specific questions about their level of conflict with their spouses/partners around various issues such as chores and responsibilities, children, money, not showing love/affection, sex, religion, leisure time, drinking, other women/men, and in-laws. Items were rated on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = never/hardly ever to 3 = often). Mean scores were computed for cases with scores on at least 5 of the 10 items. Higher scores indicated more conflict with spouse/partner. The scales demonstrated adequate internal consistency for this sample with a coefficient alpha of .80 for mothers and .81 for fathers.

Father engagement

Fathers were asked to rate how frequently they engaged in three types of activities (i.e., verbal stimulation, caregiving, and physical play) with their infants. We calculated the mean for each type of engagement. For the verbal stimulation subscale fathers were asked to rate how frequently (4-point Likert scale) they engaged with their infants in a typical week in the following activities: reading books, telling stories, and singing songs (alpha = .70). For the caregiving subscale, on a 6-point Likert scale, fathers were asked to rate how frequently they engaged in the following caregiving activities in the past month: changing diapers, preparing meals or bottles, feeding their children, putting their children to sleep, washing or bathing their children, and dressing their children (alpha = .80). For the physical play subscale fathers were asked to rate, on a 6-point Likert scale, how often they engaged in the following physical contact activities in the past month: tickling their children and blowing on their bellies, and holding their children to play with them (alpha = .71).

Control Variables

In this study, we controlled for father employment and child age. One study found that fathers’ working hours may influence the amount of time they spend with their children, which, in turn, could influence how fathers engage with their infants (Hofferth & Anderson 2003). We controlled for child age because of the differences in the timing of the child outcome data collection within each round of the ECLS-B. For example, at the 9-month data collection, children’s age ranged from 8 to 13 months at the time of the home visits.

Analysis Plan

To address our research questions, we conducted a path analysis, a type of structural equation model. First, from the literature review and based on our conceptual model of father engagement (see Figure 1) we selected variables representing African American and Latino origin, parents’ depressive symptoms, fathers’ education, infants’ age, marital status, mothers’ and fathers’ report of marital/couple conflict, and father engagement (e.g., verbal stimulation, caregiving, and physical play activities). The father engagement variables were used as three separate dependent variables and all the other variables were used as independent variables in the final model. We first entered the variables noted above and ran the model for the full sample, with race/ethnicity included as two dummy variables (African American (1) vs. White (0) and Latino (1) vs. White (0) using EQS v. 6.1 (Bentler, 2005). The final model was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Chi-square index, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). To test whether the model held across the three racial groups, we then ran a multigroup analysis for White, African American, and Latino fathers. We ran this twice, once allowing all paths to vary and, second, constraining all paths to be equal. We tested a few of the paths that appeared to differ across the three groups in the unconstrained model. The coefficients for African American and Latino fathers were contrasted with White fathers. We tested whether coefficients were similar or different by constraining the model so that only that specific model parameter was similar across two groups and comparing it with a model without that constraint. If the chi-square for the change was not significant, then the coefficients did not differ from each other. If the chi-square for the change was significant, this suggested that the coefficients differed. Effect sizes were calculated by dividing the unstandardized coefficient by the standard error of the dependent variable (Cohen, 1988).

Only one percent of data were missing at baseline and there were no significant differences in the amount of missing data by ethnic group. Missing data were included in the model and the results estimated using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in EQS (Enders, 2006). FIML uses an algorithm to provide maximum likelihood estimation; it does not impute missing values (Acock, 2005). This method has been shown to offer several advantages over more traditional approaches (Acock, 2005). All data were weighted using the appropriate longitudinal weights (Nord et al., 2006).

Results

Descriptive Results

In Table 1, we show the weighted sample characteristics of fathers and their infants. Results from ANOVAS suggested that the means or proportions in the groups were not equal. We then ran multiple comparisons between selected groups and used the Bonferroni test to correct for type I error. Results showed that although fathers and mothers, in the total sample, reported a moderate number of depressive symptoms, African American reported more depressive symptoms than White and Latino fathers (t (525) =-5.75, p<.0001; t (725) =-2.49, p<.04, respectively). White fathers reported more depressive symptoms than Latino fathers (t (1,361) =4.76, p<.0001). Similarly, African American mothers reported more depressive symptoms than White mothers (t (539) =-2.82, p<.01). In the total sample, both mothers and fathers reported relatively high levels of conflict. However, African American fathers reported significantly more couple conflict than White and Latino fathers (t (894) = -4.48, p<.0001; t (1,361) = -4.55, p<.0001). African American mothers reported more conflict than White mothers (t (519) =2.47, p<.01). White and Latino mothers reported similar levels of conflict with their partners. Most Latinos (70%) had completed high school or less, compared to about half of African American fathers (46%) and a third (30%) of White fathers. In contrast, almost 70% of White, 54% of African American, and 30% of Latino fathers reported having completed some college or a college education.

Table 1 also shows mean levels of father-reported engagement with their infants by race/ethnicity. All fathers engaged in high levels of caregiving, moderately high levels of physical play, and moderate levels of verbal stimulation of their infants. There were group differences only for caregiving and physical play. African American fathers reported engaging in significantly more caregiving activities than White and Latino fathers, whose levels of caregiving were similar. Both Latino and African American fathers reported engaging in higher levels of physical play than White fathers (t (4,684) =14.50, p<.0001; t (3,051) =10.63, p<.001, respectively).

Multivariate Results

Several model-data fit indices were used to test whether the full model differed significantly from the null model (i.e. with no paths) for the full sample and for each subsample. Using the CFI and RMSEA fit indices and according to Hu and Bentler’s (1999) rule of thumb (CFI >.95; RMSEA<.06), the final model (Tables 2-4) was a good fit for the total sample (i.e. including all three racial groups) and for each type of father engagement (CFI=0.972, RMSEA=0.04). The RMSEA was between .038 and .048 with 90% confidence. The likelihood ratio Chi-Square was 249.39, DF=24. In other words, the variables in the model, including marital status, mother and father report of couple conflict, father’s education, race/ethnicity, fathers’ working hours, and infant’s age helped us predict three types of father engagement with infants. The overall model explained 2% of the variance in caregiving, 8% in physical play, and 2% in verbal stimulation.

Table 2.

Path Coefficients for Verbal stimulation

| Variables | All Model | African American | Latino | White | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | |

| Paternal depressive sympt | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Maternal depressive sympt | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.05 | -0.08 | 0.03 | -0.13 * | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.03 |

| Married | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.04 |

| Conflict – father report | -0.10 | 0.02 | -0.14 * | -0.22 | 0.02 | -0.30 * | -0.12 | 0.03 | -0.16 * | -0.09 | 0.02 | -0.12 * |

| Conflict – mother report | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.01 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.03 |

| Infant age (months) | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 * | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.07 * | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.04 * | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.04 * |

| Father Working Hours | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.00 * | -0.06 | 0.00 | -0.00 * | -0.04 | 0.00 | -0.00 * | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.00 * |

| African American | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| Latino | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Some college | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.09 * | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.08 * |

| College plus | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.13 * | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.21 * | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.12 * | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.15 * |

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2= .02 | R2=.12 | R2=0.37 | R2=.03 | |||||||||

Note:

p < .05,

S.E.=Standard Error

Table 4.

Path Coefficients for Physical Play

| Variables | All Model | African American | Latino | White | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | |

| Paternal depressive symptoms | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.04 | -0.09 | 0.03 | -0.18 * | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.04 |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.21 * | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.17 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.02 |

| Married | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.22 * | -0.24 | 0.03 | -0.52 * | -0.16 | 0.03 | -0.37 * | -0.15 | 0.03 | -0.32 * |

| Conflict – father report | -0.05 | 0.03 | -0.08 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.04 * | -0.05 | 0.03 | -0.09 * |

| Conflict – mother report | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.05 | -0.06 | 0.03 | -0.1 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Infant age (months) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 * | -0.04 | 0.01 | -0.02 * | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 * |

| Father Working Hours | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.00 * | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.00 * | -0.01 | 0.00 | -0.01 | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.00 * |

| African American | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.41 * | |||||||||

| Latino | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.31 * | |||||||||

| Some college | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.02 | -0.11 | 0.03 | -0.19 * | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.13 * | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.07 * |

| College plus | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.12 * | -0.06 | 0.03 | -0.11 * | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.03 * | -0.12 | 0.03 | -0.21 * |

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2=.076 | R2=.097 | R2=.056 | R2=.051 | |||||||||

Total sample

In the full sample, there were no differences in verbally stimulating activities by race/ethnicity (Table 2, column 1). Table 3, column 1, shows that after controlling for a number of variables, African American fathers participated in more caregiving activities than White fathers (B = .19, p < .05) and Latinos engaged in less caregiving than White fathers (B = -0.06 p < .05); the effect sizes were .26 and .08, respectively. Table 4, column 1, shows that both Latino and African American fathers participated in more physical play activities than White fathers (B = .41 and =.31, p < .05, respectively; the effect sizes were .50 and .39, respectively).

Table 3. Path Coefficients for Caregiving.

| Variables | All Model | African American | Latino | White | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | Beta | S.E. | B | |

| Paternal depressive symptoms | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 * | -0.16 | 0.03 | -0.34 * | -0.09 | 0.03 | -0.19 * | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.07 * |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.10 * | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 * |

| Married | -0.08 | 0.03 | -0.15 * | -0.15 | 0.03 | -0.30 * | -0.07 | 0.03 | -0.15 * | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.19 * |

| Conflict – father report | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.05 * | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | -0.04 | 0.02 | -0.05 * | -0.05 | 0.03 | -0.07 * |

| Conflict – mother report | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 | -0.04 | 0.03 | -0.06 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Infant age (months) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 * | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Father Working Hours | -0.07 | 0.00 | -0.00 * | -0.03 | 0.00 | -0.00 | -0.02 | 0.00 | -0.00 | -0.05 | 0.00 | -0.00 * |

| African American | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.19 * | |||||||||

| Latino | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 * | |||||||||

| Some college | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 * | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| College plus | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.05 | -0.10 | 0.03 | -0.18 * | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.03 | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.01 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2=.023 | R2=.058 | R2=.022 | R2=.018 | |||||||||

Note:

p < .05,

S.E.=Standard Error

Verbal stimulation

Fathers who had some college or had completed college engaged in higher levels of verbally stimulating activities with their infants than fathers who finished high school but did not attend college (B = .09 p < .05; effect size = .12) (Table 2). Greater father-reported conflict was associated with fewer verbally stimulating activities (B = -0.14 p < .05 effect size = .19).

Caregiving

Father’s educational level was not associated with caregiving (Table 3). Fathers who were married reported less involvement in caregiving than fathers who were not married to their partners (B = -0.15 p < .05; effect size = .21). As with verbal stimulation, fathers reporting more couple conflict were less involved in caregiving; this was a small effect (B = -0.05 p < .05, effect size = .07).

Physical play

Fathers who had completed college or more were less involved in physical play than fathers who had not completed college (B = -0.12 p < .05; effect size = .15) (Table 4). Compared to cohabiting fathers, married fathers were less likely to engage in physical activities with their infants (B = -0.22, p < .05, effect size = .27). Greater father-reported conflict was associated with less physical play (B = -0.001 p < .05, effect size = .001).

Differences in the models for the three race/ethnic groups

Tables 2 to 4, columns 2 to 4, show the path coefficients for each type of father engagement for the three race/ethnic groups. For verbal stimulation, the model explained 12% of the variance for African Americans, 37% for Latinos, and 3% for Whites. For caregiving, the model explained 6% of the variance in African American, 2% in Latino, and 2% in White fathers. For physical play, the model explained 10% of the variance for African Americans, 6% for Latinos, and 5% for Whites. An overall comparison of the fit of the models for the three race/ethnic groups found that the model fit was excellent when it was run with all constraints, that is, with identical coefficients for separate race/ethnic groups (CFI=0.996, RMSEA=0.014; with 90% confidence, the RMSEA was between .005 and 0.021). The likelihood ratio Chi-Square was 45.342, DF= 27. There was no significant difference between the fully constrained model and one freeing all coefficients (CFI =. 997. RMSEA=.02, Range =.007-.030).

Overall, therefore, the model does not differ by race/ethnicity. That is, fathers’ human capital (i.e., education, employment), mental health (i.e., depressive symptoms), and contextual sources of stress and support (i.e., marital status and couple relationship quality) predicted levels of father-infant engagement for the three race/ethnic groups. Fathers with similar characteristics engaged their infants at similar levels in verbal stimulation, caregiving, and physical play. For example, marital status was significantly associated with less physical play across the three race/ethnic groups (B = -0.52, -.37, and -.32, p < .05 for African American, Latino, and White, respectively; the effect sizes were .66, .45, and .42 respectively). Maternal depressive symptoms were significantly associated with more paternal caregiving across all three groups (B = 0.17, .10, and .06, p < .05 for African American, Latino, and White, respectively; the effect sizes were .22, .13, and .10 respectively). After examining the models more closely, we found that only two coefficients differed across the three race/ethnic groups. For physical play, African American mothers who had more depressive symptoms had partners who engaged in more physical play than White mothers (B = 0.21 p < .05; effect size = .27).

Discussion

As one of the few studies using nationally representative data on fathers, this study extended previous research on father engagement to infants and minority populations. Specifically, this study was guided by two research questions: (1) In a model of father engagement that includes fathers’ human capital, mental health, and family relationships, do race/ethnicity predict different levels of involvement? And (2) Are models similar across race/ethnic groups? We expected that levels of father engagement would differ across race/ethnic groups but we did not expect any racial and ethnic differences in the set of factors that predict father engagement with infants.

With respect to our first research question, we found that our model of predictors of father engagement based on current scholarly thinking (Belsky, 1984; Pleck, 1997) was significantly linked to father engagement, although there were some differences by levels of engagement. As expected, the model for the total sample revealed significant associations between fathers’ education levels, employment hours, marital status, and father report of marital conflict and types of father engagement (Belsky, 1984; Black, Dubowitz, & Starr, 1999; Cabrera et al., 2006; Tamis-LeMonda,Shannon, Cabrera, & Lamb, 2004). We note that the effect sizes were small. Moreover, this model across race/ethnic groups explained only two percent of the variance in levels of father engagement suggesting that other variables (child age, motivation to father a child, maternal gatekeeping, maternal employment, kin support) not included in this model might be more predictive of father-infant engagement. Parents who might be experiencing depressive symptoms, arguing with their partners, or stressed due to lack of employment might find it easier to neglect the demands of toddlers, who are more independent, than the demands of infants, who completely rely on their parents for basic caregiving. There is a need for more longitudinal studies on father involvement across developmental periods.

It is also worth noting that our model explained a substantial amount of variance for analyses when we ran them separately for each group (37% in verbal stimulation for Latinos and 12% for African American in contrast to 3% for White fathers). This suggests that our model of father engagement explains more of the variance in father engagement for Latino fathers than it does for African American and White fathers. Unobserved factors such as motivation to parent and maternal gatekeeping, for example, might be more important for African American and White families than for Latinos. This is a testable hypothesis. Other cultural variables may be relevant for African American and White fathers’ engagement. For example, for African American fathers issues of paternity establishment, multipartner fertility, and kin support (or lack of) might be better predictors of how engaged fathers are with their children (Morgan et al., 2008). This issue merits further research.

Our hypothesis that parents’ depressive symptoms would be linked to father engagement was partially supported for minority fathers, not for white fathers, and only for caregiving and physical play; however, the effect size was small. Across all three racial/ethnic groups, fathers whose partners reported more depressive symptoms engaged in higher levels of caregiving than men whose partners reported fewer depressive symptoms. However, the influences of maternal depressive symptoms on father’s verbal stimulation and physical play were only significant for African American fathers. African American men whose partners reported more depressive symptoms were less engaged in verbally stimulating activities but more engaged in physical play than fathers whose partners reported fewer depressive symptoms. That caregiving is greater when a father’spartner is depressed makes sense as does increased physical play; fathers maybe compensating when mothers’ depressive symptoms make them unavailable. It is unclear, however, why verbal stimulation is lower under these circumstances, particularly for African American men. These findings are difficult to interpret and suggest that further research addressing the differential effect on mental health of family processes in minority families is needed.

Although the coefficients were small, fathers with more human capital (college education) read and sang songs to and engaged in verbally stimulating activities with their infants at higher levels than fathers who had only completed high school. Higher levels of education were not linked to levels of caregiving and were negatively linked to physical play. Keeping in mind that fathers across the three groups engaged in verbally stimulating activities less frequently than they did in caregiving or physical play, this finding suggests that because fathers are already engaged in caregiving and physical play, which can promote positive parent-child relationships, programs and policies could specifically target father involvement in literacy activities during infancy. Efforts to engage fathers, particularly low-income fathers, in literacy-type activities in early childhood education settings have proven difficult for several reasons, including men’s own literacy skill levels (Trepper, Hawkins, & Fagan, 2001). Perhaps encouraging men to begin to read to their children during infancy can build their own sense of competence, which, over time, can only strengthen this behavior.

As hypothesized, we found that marital status predicted father’s level of engagement but in the opposite direction expected. Controlling for fathers’ working hours, we found that married fathers reported lower levels of engagement in caregiving and physical play (but not in verbal stimulating activities) than cohabiting fathers. This finding is consistent with recent research using the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing dataset that found that previously cohabitating fathers were more involved with children than previously married fathers (Laughlin et al., 2009). It is unclear, however, why married fathers are less engaged with their infants than cohabiting fathers. One hypothesis is that cohabiting fathers are motivated to demonstrate their commitment to the mother and child in order to marry the mother (England & Edin, 2007; Hofferth & Anderson, 2003). It is also possible that division of labor among partners is more prescriptive in married couples than cohabiting couples (England & Edin, 2007). This could explain the lesser participation of married fathers in physical play and caregiving but equal involvement in verbal stimulation. Further research needs to be conducted to understand the links between marriage and levels of father involvement, especially for African American families.

We also found that fathers who reported more conflict with their partner were less engaged with their infants across all three types of activities than fathers who reported less conflict. The coefficients were small for couple conflict (with the largest for African Americans, B=.30, p<.05 for verbal stimulation) and moderate to large for marital status (with the largest for African Americans, B=.52, p<.05 for physical play). One testable hypothesis might be that in families that are characterized by conflict, fathers withdraw from their children resulting in less engagement. There is some evidence that hostility between parents has a direct influence on the time that fathers spend engaging with their children in various activities (Cabrera et al., 2007; Cummings et al., 2000, Fagan & Barnett, 2003). These findings have important implications for child well-being given that studies have shown that low-income fathers’ positive involvement with their children can make a difference in their children’s language and cognitive skills (Black et al., 1999; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004).

Another important finding is the presence of ethnic differences in levels of father engagement with infants, after controlling for a host of variables. Consistent with previous findings based on older children that show that minority fathers engage in higher levels of caregiving than other fathers (Ahmeduzzaman & Roopnarine, 1992; Hossain & Roopnarine, 1993, 1994; Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004; Roopnarine, 2004; Tooth & Xu, 1999; Yeung et al., 2001), we find the same pattern with fathers of infants. Although all fathers reported being engaged with their infants in physical play and caregiving activities, African American and Latino fathers were more engaged in these activities than White fathers. These group differences remained after controlling for fathers’ human capital, infants’ age, fathers’ working hours, and couple conflict. Our hypothesis that these differences would disappear after accounting for fathers’ human capital was not supported. A possible explanation is that these differences reflect African American values of family closeness and connection (McAdoo, 1993) and Latinos’ emphasis on familism (Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002; Grau et al., 2009). To date, this view of family involvement and commitment has generally applied to mothers rather than fathers because fathers, especially African American fathers, have been perceived to be more likely to be absent (or nonresident) from their children’s lives. In our study of families in which both biological fathers and mothers live with their infants, there is evidence that African American fathers are highly engaged with their infant, challenging the popular perception of noninvolvement. This finding is consistent with new and emerging views on positive fathering in African American families (Smith, Krohn, Chu, & Best, 2005).

Also notably, we found that across race/ethnic groups, married fathers reported being less engaged in caregiving and physical play than cohabiting fathers, and the effect size was medium to large. However, we also found that fathers’ depressive symptoms and the quality of his relationship with his partner (i.e., couple conflict, and marital status) were significantly associated (the coefficient was moderate) with less caregiving and physical play among African American fathers, who also reported higher levels of depressive symptoms and couple conflict than other fathers. Given that couple conflict and depressive symptoms have been linked to negative parenting (Cummings et al., 2000), not engaging with children when one is depressed and upset might be beneficial for them. On the other hand, children benefit from positive father involvement and so children, especially low-income children, whose fathers are not positively engaged, might be at a further disadvantage. Thus, focusing on partner conflict and parents’ mental health might be an important target of intervention for programs and policies.

There were no race/ethnic group differences for father engagement in verbally stimulating activities; all fathers engaged in these activities at lower levels than they did in other types of engagement. Although the coefficient was small, only fathers’ education (college level) was related to higher levels of engagement in verbally stimulating activities. Minority fathers who had a college education were more likely to read to their children than fathers with only a high school education. This means that our hypothesis that ethnic/race differences are mainly explained by fathers’ human capital is partially supported only for one type of father engagement, namely verbally stimulating activities. This is a new finding suggesting that deconstructing the broad term of “father engagement” has important implications for tailoring programs and policies to address specific families’ needs. Given that many minority children are at risk for school failure because of poor language skills, investing in programs that encourage fathers to read to their children as early as nine months could be a low-investment and potentially high-dividend program strategy.

With respect to our second research question, we found that our conceptual model of predictors of father engagement does not vary by race/ethnicity for two types of father engagement: verbal stimulation and caregiving. Although levels of father involvement varied across race/ethnic groups, the conceptual model fit the data equally well for all three groups for these two types of father engagement. There was, however, one significant race/ethnic difference in the factors associated with fathers engaging in physical play. That is, the pathways from our predictors to father engagement were the same for all fathers across race/ethnicity, except for physical play. For physical play, compared to White mothers who reported high levels of depressive symptoms (B=-0.02, p,.05), African American mothers who reported high levels of depressive symptoms had partners who engaged in more physical play (B =.21, p<.05). There may be cultural differences in the way that minority parents respond to stressful situations (Sullivan, 1993). Further research needs to be conducted to understand how cultural expectations and beliefs influence the level and type of father engagement with their infants.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

There are several strengths of this study. First, the present analysis is based on a nationally representative sample of infants and their fathers. Second, it uses fathers’ reports of their own demographic characteristics, fathering behaviors, and family relationships, rather than mother’s reports of these variables. Third, the present analysis examines an important developmental period, infancy. Fourth, it is able to test hypotheses about differences and similarities in how fathers engage with their infants across race/ethnic groups.

One weakness of the study is the lack of inclusion of maternal involvement in the model. Based on past findings with older children that fathers make a unique contribution to their children’s development, over and above mothers’ contribution (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004), we suggest that our findings would hold had we included mother’s reports of engagement, but we cannot be certain. We did not include maternal report of these activities because the ECLS-B did not collect these data. A second weakness is that the data were collected at the same point in time; causality cannot be determined. A third weakness is related to measurement. The self-report measure of father engagement is not optimal to assess father engagement; observations of father-child interactions are preferred. Fathers’ self-report may reflect fathers’ desires to appear more engaged than they might be. The self-report measure of couple conflict is also limited, but at least is reported by the father himself. Another potential problem might be shared variance because fathers reported on both their demographic profile and their levels of engagement.

Overall, the study highlights the importance of considering not only the level, but also type of engagement. This is especially important if the intent is to promote and encourage types of father engagement that are linked to improved child outcomes. For example, across race/ethnic groups, fathers engage in high levels of caregiving, but engage less in verbally stimulating activities; the latter is particularly important for language and cognitive development (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2004). An implication of this study is the need to encourage fathers to engage in literacy activities with their infants.

Another finding worth highlighting, because of its relevance for practitioners interested in shaping fatherhood programs, is the importance of family processes such as conflict and family structure in promoting father engagement; the effect of these variables on father engagement is strongest for African American families. Fathers who report more conflict with their partners tend to engage less in verbally stimulating, caregiving, and play activities with their infants than their counterparts. We expected this result. What was unexpected is the finding that marriage does not necessarily mean more father engagement. In this study, cohabiting biological fathers were more engaged in caregiving and physical play activities than married fathers, after controlling for fathers’ working hours and couple conflict. One possible explanation is that gender roles are less firmly fixed in cohabiting compared to married couples; thus, cohabiting fathers may do an increased share of caregiving compared to married fathers (England & Edin, 2007). It may also reflect cohabitating men’s greater commitment to the mother; unmarried fathers may need to prove their value compared those already married (England & Edin, 2007). Further research is needed to understand how marital status is linked to levels of father engagement and the mechanism that might explain it. Finally, it is worth noting that only college-level education predicted to father engagement in verbally stimulating activities in the total sample. This is an important finding given the link between verbal and cognitive stimulation and school readiness, even for very young children.

In summary, our findings show that fathers are engaged with their infants in high levels of caregiving and physical play but less so in verbal stimulating activities. Predictors of father engagement depend on the type of father engagement; fathers’ human capital (college level) is most predictive of fathers engaging with their infants in verbally stimulating activities. Higher levels of mothers’ psychological well-being are related to more father engagement in caregiving and physical play and lower quality of couple relationships consistently predicted to less engagement in caregiving and physical play. This is especially important for African American families because in this study they report higher levels of conflict and depressive symptoms than fathers in the other groups. Finally, our model of father engagement reveals only one race/ethnic difference for physical play. African American mothers’ depressive symptoms predict father engagement in physical play differently than White mothers’ depressive symptoms predict father engagement for White fathers. Perhaps cultural differences better express themselves in play rather than in other types of engagement with children. This highlights the importance of continuing to understand the differences and similarities across race/ethnic groups in order to guide program and policy development aimed at promoting positive father involvement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmeduzzaman M, Roopnarine JL. Sociodemographic factors, functioning style, social support, and fathers’ involvement with preschoolers’ in African-American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:699–707. [Google Scholar]

- Allen SM, Hawkins AJ. Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers’ beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father engagement in family work. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61(1):14. [Google Scholar]

- Bardige B, Bardige KM. Talk to me, Baby! Supporting language development in the first 3 years. Zero to Three. 2008:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS Windows 6.1. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing rhythms of American family life. New York, NY: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Dubowitz H, Starr RH. African American fathers in low-income, urban families: Development, behavior, and home environment of their three-year-olds. Child Development. 1999;70:967–978. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone C, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Correlates in parenting style in predominantly working- and middle-class African American mothers. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Markman L. The contributions of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. The Future of Children. 2005;15:139–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayfield A. Juggling jobs and kids: The impact of employment schedules on fathers’ caring for children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57(2):321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bronte-Tinkew J, Carrano J, Horowitz A, Kinukawa K. Involvement among resident fathers and links to infant cognitive outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(9):1211–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy-Herb HE, Gibbons C, Omar MA, Schiffman RF. Low-income fathers and their infants: Interactions during teaching episodes. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20:305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. The social context of language acquisition. Language & Communication. 1981;1:155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Buriel R. Childrearing orientation in Mexican American families: The influence of generation and sociocultural factors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55:987–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Fagan J, Farrie D. Explaining the long reach of fathers’ prenatal involvement on later paternal engagement with children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:1094–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Fitzgerald H, Bradley R, Roggman L. Modeling the dynamics of paternal influences on children over the life course. Applied Developmental Science. 2007;11(4):185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Garcia Coll C. Latino fathers: Uncharted territory in need of much exploration. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of father in child development. 4. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 417–452. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Ryan R, Jolley S, Shannon J, Tamis-Lemonda C. Low-income, nonresident father involvement with their toddlers: Variation by fathers’ race/ethnicity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(4):643–647. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Shannon JD, West J, Brooks-Gunn J. Parental interactions with Latino infants: Variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1190–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bradley RH, Hofferth S, Lamb ME. Fatherhood in the twenty-first century. Child Development. 2000;71(1):127–136. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos R. Considerations for studying father engagement in early childhood among Latino families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:133–160. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodríguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras J, Kerns K, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran DL. African American fathers: A decade review of the literature. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services. 1997;11:340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Stability and change in paternal involvement among urban African American fathers. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13(3):416–435. [Google Scholar]

- Coley R. (In)visible men: Emerging research on low-income, unmarried, and minority fathers. American Psychologist. 2001;56:743–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL, Whitbeck LG. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63:526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings ME, Davies P, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Raymond JL. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 196–221. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger SK, Radin N. Absent does not equal uninvolved: Predictors of fathering in teen mother families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52:636–642. [Google Scholar]

- De Wolff M, Van Ijzendoorn M. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Development. 1997;68:571–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W, Kouneski E, Erickson M. Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP. Children’s play in cross-cultural perspective: A new look at the six cultures study. Cross-Cultural Research. 2000;34(4):318–338. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP, Sheridan SM, Knoche L. Parent-child relationships in early learning. In: Baker E, Peterson P, McGaw B, editors. International encyclopedia of education. Oxford, England: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Analyzing structural equation models with missing data. In: Hancock GR, Mueller RO, editors. Structural equation modeling: A second course. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2006. pp. 313–342. [Google Scholar]

- England P, Edin K. Unmarried couples with children. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle J, Astone N. Some practical guidelines for measuring youth’s race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Child Development. 1994;65:1521–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. A preliminary study of low-income African American fathers’ play interactions with preschool-age children. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J. Correlates of low-income African American and Puerto Rican fathers’ involvement with their children. Journal of Black Psychology. 1998;24:351–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Barnett M. The relationship between maternal gatekeeping, paternal competence, mothers’ attitudes about the father role, and father engagement. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(8):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: Key to national indicators of well-being. National Center for Health Statistics; Washington, D.C: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, Moore D. The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;17:65–79. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.17.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LE, Black MM, Minor S, Abel Y, Papas MA, Bentley MA. Young, disadvantaged fathers’ involvement with their infants: An ecological perspective. Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2002;31:266–276. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau J, Azmitia M, Quattlebaum J. Latino families: Family and developmental processes. In: Villaruel FA, Carlo G, Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera N, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook on U.S. Latino psychology. New York, NY: Sage; 2009. pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Harris K. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development. Demography. 2000;37(4):431–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley T. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley T. The social world of children learning to talk. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman RH, Wolfe BS. Succeeding generations: On the effects of investments in children. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review. 2006;26:55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL. Race/ethnic differences in father engagement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Hofferth SL, Anderson K. Are all dads equal? Biology vs. marriage as basis for paternal investment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:213–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Z, Roopnarine J. Division of household labor and child care in dual earner African-American families with infants. Sex Roles. 1993;29:571–583. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Z, Roopnarine JL. African-American fathers’ involvement with infants: Relationship to their functioning style, support, education, and income. Infant Behavior and Development. 1994;17:175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Mincy R, Garfinkel I. Child support obligation of low income fathers. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67(5):1213–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Elster AB. Adolescent mother-infant-father relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1985;20:504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb ME, Lewis C. The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 4. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 272–306. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin L, Farrie D, Fagan J. Father involvement with children following marital and non-marital separations. Fathering. 2009;7(3):226–248. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Father engagement in the lives of mainland Puerto Rican children: Contributions of nonresident, cohabiting and married fathers. Social Forces. 2001;79:945–968. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman R. A national profile of fathers. In: Lerman R, Ooms T, editors. Young unwed fathers Changing roles and emerging policies. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993. pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo JL. The roles of African American fathers: An ecological perspective. Families in Society, Special Issue: Fathers. 1993;74(1):28–35. [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Price SJ, Fine MA, Serovich J. Predictors of single, non-custodial fathers’ physical involvement with their children. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1992;153:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Fragile families and the reproduction of poverty. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621(1):111–131. doi: 10.1177/0002716208324862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Mirande A. Ethnicity and fatherhood. In: Bozett FW, Hanson S, editors. Fatherhood and families in cultural context: Focus on men. New York. NY: Springer; 1991. pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mirande JL. Hombres y machos: Masculinity and Latino culture. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP Executive Committee. Designing new models for explaining family change and variation Recommendations to the Demographic and Behavioral Sciences Branch of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2008 Retrived from http://www.soc.duke.edu/~efc/Docs/pubs/EFCFINALAUGappendice.pdf.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Early childhood longitudinal study, birth cohort: 9-month public-use data file users’ manual (NCES Publication No. 2006–046) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2005a. [Google Scholar]