Abstract

In many macroorganisms, the ultimate source of potent biologically active natural products has remained elusive due to an inability to identify and culture the producing symbiotic microorganisms. As a model system for developing a meta-omic approach to identify and characterize natural product pathways from invertebrate-derived microbial consortia we chose to investigate the ET-743 (Yondelis®) biosynthetic pathway. This molecule is an approved anti-cancer agent obtained in low abundance (10−4–10−5% w/w) from the tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata, and is generated in suitable quantities for clinical use by a lengthy semi-synthetic process. Based on structural similarities to three bacterial secondary metabolites, we hypothesized that ET-743 is the product of a marine bacterial symbiont. Using metagenomic sequencing of total DNA from the tunicate/microbial consortium we targeted and assembled a 35 kb contig containing 25 genes that comprise the core of the NRPS biosynthetic pathway for this valuable anti-cancer agent. Rigorous sequence analysis based on codon usage of two large unlinked contigs suggests that Candidatus Endoecteinascidia frumentensis produces the ET-743 metabolite. Subsequent metaproteomic analysis confirmed expression of three key biosynthetic proteins. Moreover, the predicted activity of an enzyme for assembly of the tetrahydroisoquinoline core of ET-743 was verified in vitro. This work provides a foundation for direct production of the drug and new analogs through metabolic engineering. We expect that the interdisciplinary approach described is applicable to diverse host-symbiont systems that generate valuable natural products for drug discovery and development.

Keywords: Biosynthesis, ET-743, E. turbinata, metagenomics, metaproteomics, natural products, Pictet-Spenglerase, symbiont, tetrahydroisoquinoline, Yondelis

INTRODUCTION

One of the major challenges in gene and metabolic pathway discovery involves access to genomes from unculturable microorganisms. Efficient methods for accessing high quality samples of DNA from specialized ecological niches have enabled metagenomic sequencing, leading to discovery of new enzymes, and in some cases partial assembly of unique genomes (1). Recent work to identify cellulases and other enzymes with bioenergy applications from the cow rumen microbial consortium established the promise of this approach. The potential for metabolic pathway assembly and deep annotation using next-generation sequencing motivated us to explore the seemingly inaccessible wealth of gene clusters for natural product biosynthesis derived from marine and terrestrial symbiont microbial consortia. Our effort has relied on the ready availability of the selected invertebrate-derived metagenomic source material, which enabled direct assembly of the target operon, and represents the development of a new strategy for secondary metabolite discovery and expansion of chemical diversity.

ET-743 (1) is a tetrahydroisoquinoline natural product with potent anti-cancer activity isolated from the tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata (2), and is clinically approved in Europe against ovarian neoplasms and sarcoma (Figure 1). The drug functions by a unique mechanism of action as it alkylates within the minor groove of DNA (3), which can lead to sequence-specific alterations in transcription (4) that trigger DNA cleavage (5). Attempts to repair ET-743 DNA lesions may cause further double-stranded DNA breaks (6). Obtaining sufficient amounts of ET-743 has been a significant challenge since it is isolated in extremely low yields from the natural source (1). Aquaculture of the tunicate (7), or total synthesis (8) cannot provide economical access to the drug (9). Thus, ET-743 for clinical application is produced semi-synthetically from fermentation-derived cyanosafracin B in seventeen chemical steps (10).

Figure 1.

Tetrahydroisoquinoline natural products, biosynthetic pathways, and a novel workflow. a) ET-743 (1) and: saframycin A (2), saframycin Mx1 (3), and safracin (4). b) ET-743 core modular NRPS proteins (EtuA1-3) and previously characterized Sfm, Saf, and Sac NRPS biosynthetic systems. NRPS domains are: AL-acyl ligase, T-thiolation, C-condensation, A-adenylation, RE-reductive. c) The experimental workflow: Ecteinascidia turbinata in its natural environment (Cory Walter, Mote Marine Laboratory) is collected (Erich Bartels, Mote Marine Laboratory), and subjected to meta-omic analysis. ET-743 related secondary metabolites were evaluated by Liquid chromatography FTICR mass spectrometry (LC-FTICR-MS/MS), total metagenomic and 16S DNA by 454 metagenomic sequencing with contig assembly, and total metaproteome by nano-LC-FTICR-MS/MS (nLC) and nLC-Orbitrap-MS/MS.

The similarity of ET-743 to three other bacterial derived natural products, including saframycin A (2) (Streptomyces lavendulae) (11), saframycin Mx1 (3) (Myxococcus xanthus) (12), and safracin B (4) (Pseudomonas fluorescens (13) suggests that the drug is of prokaryotic origin (Figure 1a) (14). The "symbiont hypothesis" has been supported for secondary metabolites isolated from invertebrates including bryostatin (15, 16), onnamide/pederin (17, 18), psymberin (19), patellamides (20), and cyanobactins (21). However, the effort reported here is the first to apply secondary metabolite analysis, cloning-independent next-generation sequencing-based metagenomics, and metaproteomics to this problem from a single sample without prior fractionation. Ascidian-derived microorganisms have previously been linked to production of the patellamides and cyanobactins—further supporting the idea of bacterial symbionts as the true producers of tunicate-derived natural products. The biosynthetic pathways for the tetrahydroisoquinoline natural products noted above have been previously characterized, thus providing a potential genetically conserved “marker” for the ET-743 system (22–24). The tetrahydroisoquinoline pathways each consist of three nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) modules and a series of allied tailoring enzymes. Each module contains three domains: adenylation (A), condensation (C), and thiolation (T) that combine the amino acid building blocks. Two of these pathways are initiated by an acyl-ligase (AL) and a T didomain. All three NRPS trimodules are terminated by a signature reductase domain (RE) that utilizes NAD(P)H to release the enzyme bound intermediate as an aldehyde. The final C domain in the saframycin pathway serves as a "Pictet-Spenglerase" to cyclize the activated intermediate (25). Recent efforts have shown that a fatty acid appended to the growing polypeptide on the NRPS T-domain is required to form the cyclic tri- and tetrapeptide tetrahydroisoquinoline core system (25). In considering a meta-omics discovery strategy, we reasoned that the ET-743 pathway would likely be comprised in part of an AL-T for initiation, three NRPS modules for elongation, and termination by an RE domain (Figure 1b, EtuA1-3).

Previous work directed toward identification of a producing organism and potential biosynthetic pathway assessed the phylogenetic diversity of bacterial species from E. turbinata as a source of ET-743 in the Mediterranean and Caribbean seas. A γ-proteobacterium Candidatus Endoecteinascidia frumentensis (AY054370) was identified as the most prevalent member from the tunicate microbial consortium at all collection sites (26, 27), providing indirect evidence for a potential bacterial producer of the ET-743 anticancer agent. We considered a cloning-independent approach that would avoid technical barriers encountered when handling environmental metagenomic DNA samples, and large clone libraries in order to gain direct access to the elusive gene cluster. Rapid advances in metagenomic and hologenomic sequencing technologies (28), as well as bioinformatic tools for contig assembly, indicated that this direct approach would provide rapid access to the desired biosynthetic system derived from a host/symbiont community.

A key issue with metagenomic DNA derived from environmental samples, and unculturable microorganisms is the lack of an in vivo genetic system to establish the identity of the biosynthetic pathway. This limitation can be overcome by in vitro characterization of heterologously expressed gene products. In vitro characterization provides a direct link between biosynthetic genes derived from field-collected samples and their corresponding metabolites, a key step toward understanding these complex systems. We also considered that metaproteomics would be an effective way to identify gene products in low abundance, particularly for samples consisting of multiple microbial species (29). Direct amino acid sequence evidence for predicted biosynthetic proteins can effectively link gene-based bioinformatics to in vitro biochemical function in diverse microbial symbiont-host systems.

Herein, we describe the identification and initial biochemical characterization of the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway from the host/symbiont community derived from E. turbinata. After confirming the presence of the tetrahydroisoquinoline secondary metabolites from the animal, metagenomic sequencing was conducted to identify the target biosynthetic genes. High-resolution mass spectrometry was then used to mine the metaproteome for the presence of the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway enzymes predicted from gene cluster sequence analysis. Finally, enzymatic activity for a key enzyme to form the tetrahydroisoquinoline core was verified in vitro with a model substrate to corroborate the identity of the metabolic pathway (Figure 1c). This knowledge enables a clear path for accessing ET-743 and new analogs through heterologous expression technologies (30, 31), and provides a general strategy for identification and characterization of host/symbiont derived natural product systems.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Secondary metabolite identification as a starting point for the "ET-743 bacterial symbiont producer" hypothesis

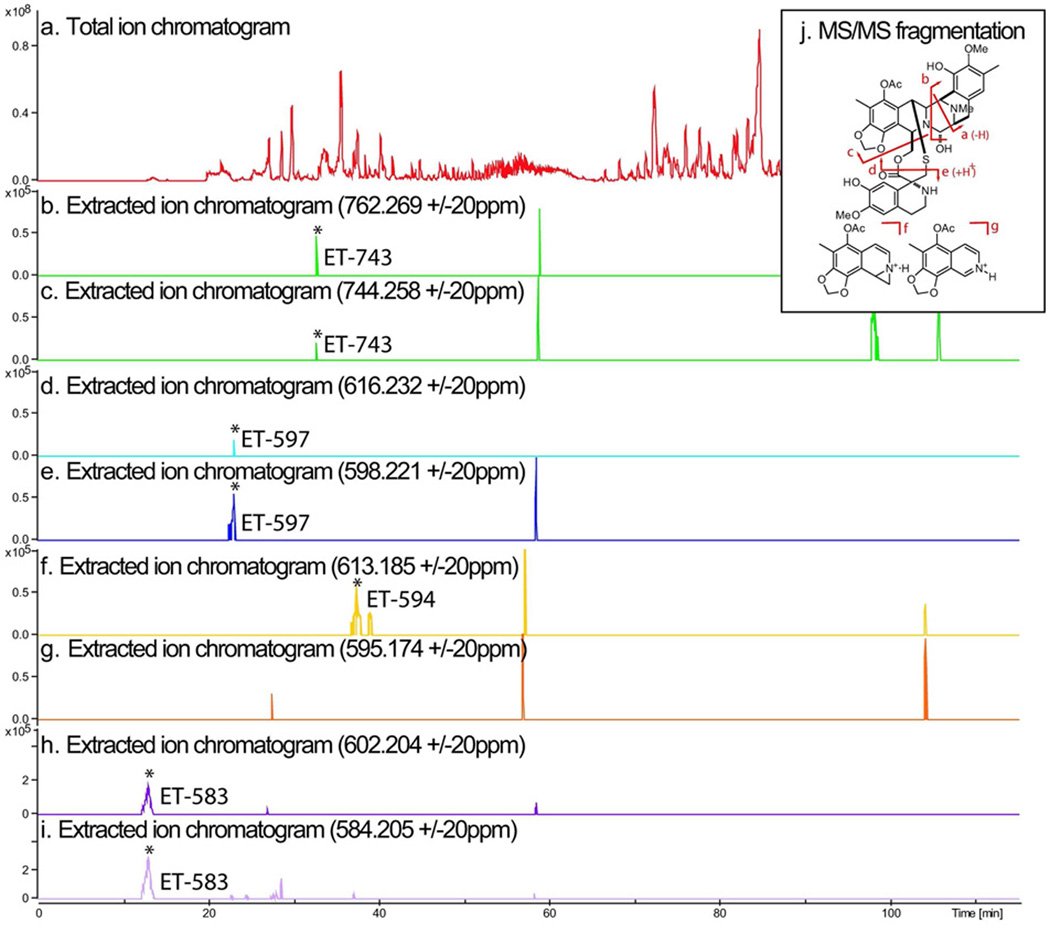

We confirmed that field-collected tunicate samples of E. turbinata from the Florida Keys contained ET-743 and related metabolites using high-resolution, high-mass accuracy, liquid chromatography-Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (LC-FTICR-MS). Known biosynthetic precursors were identified from the tunicate by extracted ion chromatograms at ±20 ppm, including the M + H+ and (M - H2O) + H+ for ET-743 (1), ET-597 (19), ET-594 (21) and ET-583 (18) (Figure 2). Confirmation by LC-MS/MS was performed on-line with FTICR-MS and an iontrap-mass spectrometer (IT-MS). Since all four compounds identified had previously been characterized by MS/MS, assignment of product ions was straightforward (Table S1) as observed fragmentation was consistent between earlier studies using fast atom bombardment (FAB)-collision induced dissociation (CID) (32), and our work with electrospray ionization (ESI)-(CID) on FTICR and IT instruments. The presence of both ET-743 and presumed precursors strongly suggested that ET-743 biosynthesis occurred within the field-collected animal, and thus that the producing symbiont was present.

Figure 2.

ET-743 related metabolites identified from the tunicate/microbial sample. a) LC-FTICR-MS total ion chromatogram and extracted ion chromatograms for M + H+ (b, c, f, h), and (M – H2O) + H+ (c, e, g, i) for ET-743 (1), ET-597 (19), ET-594 (21), and ET-583 (18). Y axis is in arbitrary units. All identified compounds were verified by collision induced dissociation MS/MS (Table S1).

Metagenomic sequencing and phylogenetics

Based on identification of ET-743 from E. turbinata, we prepared total hologenomic DNA from fresh field-collected tunicate samples. This DNA was used to prepare a 16S rRNA gene amplicon library and a random shotgun fragment library for 454 based FLX pyrosequencing. Raw reads from the first shotgun sequencing run, and an assembly of these data were filtered using relatedness of the translated protein sequences to the saframycin and safracin non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) (MXU24657, DQ838002, AY061859) using BLASTx and tBLASTn. Linkage of these sequences was performed using a combination of traditional PCR and restriction-site PCR (RS-PCR) yielding six contigs of high interest containing putative NRPS domains for biosynthesis of ET-743 (33). A second sequencing run combined with the first generated another assembly of 839,923 reads with an average read length of 332 bp, bearing 77,754 total contigs, and 15,097 contigs larger than 500 bp. We identified a 22 kb contig that linked 4/6 of the high interest contigs from the first assembly and extended this putative NRPS-containing contig to > 35 kb using RS-PCR. This DNA fragment was PCR amplified and sequenced for confirmation. Twenty-five presumed ET-743 biosynthetic genes were identified in this contig and annotated with proposed functions which account for all of the core NRPS genes of ET-743 using BLASTx against the NCBI NR database (Figure 4a, Table S4, Genbank HQ609499). The individual genes appear to be of bacterial origin (e.g lacking introns and polycistronic), suggesting that the cluster is not derived from the tunicate genome. Although our 35 kb contig likely contains the majority of the ET-743 biosynthetic gene cluster, we expect that additional tailoring genes might be identified as additional flanking sequences are obtained. In addition to the 35 kb contig encoding a putative multi-modular NRPS, we identified sequences containing 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene fragments. One of these rRNA sequences was located in a large contig (contig00422) that we extended to > 26 kb with RS-PCR. Contig00422 (Table S5, Genbank HQ542106) contains a full 16S rRNA gene, which aligns (> 99% identity) to the 16S rRNA gene reported previously for E. frumentensis (AY054370) (DQ494516) (26, 27).

Figure 4.

ET-743 biosynthesis. a) Gene organization and names on the contiguous 35 kb gene cluster. Names relate to proposed function for each protein:  -NRPS with domains illustrated,

-NRPS with domains illustrated,  -DNA processing,

-DNA processing,  -fatty-acid enzymes,

-fatty-acid enzymes,  hydroxylase,

hydroxylase,  methyltransferases,

methyltransferases,  amidotransferases,

amidotransferases,  monoxygenase,

monoxygenase,  -pyruvate cassette,

-pyruvate cassette,  -regulatory enzymes,

-regulatory enzymes,  -drug transporter, EtuU-unknown function. b) Proposed biosynthetic pathway for ET-743. Named intermediates (characterized), enzymes (if assigned) and enzyme intermediates (thioester-bound) are shown.

-drug transporter, EtuU-unknown function. b) Proposed biosynthetic pathway for ET-743. Named intermediates (characterized), enzymes (if assigned) and enzyme intermediates (thioester-bound) are shown.

Taxonomic classification of the raw reads and of the total assembly was performed using the Metagenomic Rapid Annotations with Subsystems pipeline (MG-RAST) (34). Results from both sets were consistent, with ~40% of the classified sequences being of eukaryotic origin (mainly Ciona [sea squirt/tunicate]) and the remaining 60% being largely proteobacterial sequence (> 90%) of which there were two major populations: α-proteobacterial (primarily Rhodobacteraceae, 78 – 85%) and γ-proteobacterial (10 – 17%) (Tables 1 and S2). 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing runs identified 30 variants but only three significant ones (> 1% of the total reads) (Tables 2 and S3). The largest population of 16S rRNA gene reads was classified as Rhodobacteraceae (~78%), consistent with the classification of shotgun reads by MG-RAST. This 16S rRNA gene variant aligns to contig09113 from the shotgun sequence assembly, found previously in two of the three tunicate sampling sites from the Caribbean (clone 2j, DQ494507, 27). The second most abundant 16S rRNA gene variant is an unclassified γ-proteobacterium (~19%) that aligns to contig00422 and represents E. frumentensis in the sample. A third minor population of 16S rRNA gene reads was identified as unclassified bacteria and corresponded to one read from the shotgun sequencing runs (also identified previously, 26). These three variants account for > 97% of the 16S rRNA gene sequencing reads (Figure 3). None of these three strains form a close phylogenetic relationship with S. lavendulae, M. xanthus, or P. fluorescens, pure culture producers of the three tetrahydroisoquinoline antibiotics whose pathways have been previously characterized (11, 12, 13).

Table 1.

MG-RAST analysis of raw sequencing reads and an assembly. MG-RAST reads are classified by protein homology to a manually curated database. A cutoff of 1e-10 was used. No significant classified populations were observed beyond the Class level except in α-proteobacteria (Rhodobacteraceae). % values represent abundance at each taxonomic level. Classified results <1% are not shown (Table S2).

| Total Assembly | Raw Reads | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77,754 | 815,074 | |||

| Classified by MG-RAST: | 5,510 | 100% | 65,267 | 100% |

| Eukaryota | 2,390 | 43% | 23,413 | 36% |

| Bacteria | 3,107 | 56% | 41,651 | 64% |

| Phylum (in Bacteria) | ||||

| Bacteroidetes/Chlorobi group | 71 | 2% | 944 | 2% |

| Cyanobacteria | 60 | 2% | 684 | 2% |

| Firmicutes | 39 | 1% | 642 | 2% |

| Planctomycetes | 81 | 3% | 942 | 2% |

| Proteobacteria | 2,798 | 90% | 37,615 | 90% |

| Total | 3,107 | 100% | 41,651 | 100% |

| Class (in Proteobacteria) | ||||

| α-proteobacteria | 2,376 | 85% | 29,361 | 78% |

| ------>Rhodobacteraceae | 2,092 | 75% | 24,873 | 66% |

| β-proteobacteria | 74 | 3% | 1,179 | 3% |

| δ/ε subdivisions | 58 | 2% | 716 | 2% |

| γ-proteobacteria | 287 | 10% | 6,312 | 17% |

| Total | 2,798 | 100% | 37,615 | 100% |

Table 2.

16S rRNA gene contig identification. A 454 16S rRNA gene amplicon library was assembled at an identity of 95%. Assembled contigs were submitted to the Ribosomal Database Project 16S Classifier. It should be noted that the generally accepted confidence threshold is 80%. % values represent a bootstrap confidence estimate calculated by the RDP Classifier. Only the three largest populations are shown (Table S3).

| contig00016 | contig00021 | contig00024 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | 100% | Bacteria | 100% | Bacteria | 100% |

| Tenericutes | 11% | Proteobacteria | 74% | Proteobacteria | 100% |

| Mollicutes | 11% | γ-proteobacteria | 38% | α-proteobacteria | 100% |

| Haloplasmatales | 11% | Thiotrichales | 27% | Rhodobacterales | 98% |

| Haloplasmataceae | 11% | Thiotrichaceae | 23% | Rhodobacteraceae | 98% |

| Haloplasma | 11% | Leucothrix | 23% | Ruegeria | 26% |

| # 16S reads: | 753 | 13,264 | 55,573 | ||

| % 16S reads: | 1% | 19% | 78% | ||

| Shotgun library match: | read FS7DT | contig00422 | contig09113 |

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment tree. 16S rRNA gene sequences reported in previous E. turbinata analyses (26, 27) were aligned with 16S rRNA gene sequences representing the most abundant bacterial populations in our tunicate samples. A 16S rRNA gene-containing contig (00422) clusters with previously identified E. frumentensis.

We then sought to link the putative ET-743 35 kb biosynthetic gene cluster to the E. frumentensis 16s contig00422 by evaluating the codon usage bias. Bacteria typically do not employ synonymous codons equally and this can be exploited as a unique marker (34–35). We performed a Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) analysis using the annotated NRPS contig and contig00422 as well as ORFs identified in several contigs chosen at random. The RSCU score is the observed frequency of a codon divided by the frequency expected for equal usage of all synonymous codons, thereby making it a measure of non-randomness. RSCU scores for each codon are similar between the genes on the contig bearing the presumed NRPS biosynthetic genes and the E. frumentensis 16S rRNA gene-containing contig00422, but vary compared to RSCU scores from genes located in the random contigs from the total assembly (Figure S3). The extremely low GC content of the contig bearing the putative ET-743 NRPS genes (~23%) closely matches the GC content (26%) of the contig bearing the 16S rRNA gene corresponding to E. frumentensis, providing another strong marker of genetic linkage. On the other hand, Rhodobacteraceae appear to have uniformly high GC content (54% – 70%) according to current whole genome sequencing data, indicating that the contig containing NRPS genes is unlikely to be linked to this organism. The only fully sequenced and annotated tunicate genome, Ciona intestenilis (36), is 35% GC (NZ_AABS00000000). To account for GC bias in codon usage we included random genes from the low GC bacterium (~29%) Clostridium botulinum str. Okra. A comparison of the mean RSCU values for each codon revealed that only 12/60 values differed significantly (p<.05) between the putative ET-743 NRPS and contig00422 genes while 18/60 differed between the putative NRPS genes and random genes from C. botulinum. The significant differences between C. botulinum genes are most evident in the codons encoding isoleucine (AUU, AUC, AUA), lysine (AAA, AAG), aspartic acid (GAU, GAC), glutamic acid (GAA, GAG) and arginine (CGU, CGC, CGA, CGG, AGA, AGG). 49/60 codons differed significantly between the putative NRPS genes and random tunicate metagenome sequences. In addition to RSCU analysis we used the contig containing the 25 predicted ET-743 pathway genes in a correspondence analysis using codonW to generate a codon adaptive index (CAI). This index was then used as a reference for comparison with the same genes used in the RSCU analysis. Although all differed significantly from the NRPS contig CAI score (p<.05), the C. botulinum CAI score and random gene CAI scores differed to a larger degree (Figure S4). We also analyzed the contig bearing the NRPS genes and contig00422 with the Naïve Bayesian Classifier (NBC) tool, a composition-based metagenome fragment classifier that uses N-mer frequency profiles (37). NBC analysis based on 3- and 6-mer profiles results in high confidence classification of both contigs as γ-proteobacteria/Enterobacteriaceae. This same E. frumentensis 16S rRNA gene sequence has now been linked to E. turbinata collections from the Mediterranean, Caribbean, and Florida Keys. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the sequence contig bearing NRPS module genes are derived from the same organism as contig00422 (E. frumentensis).

EtuA1, EtuA2, EtuA3 are three putative NRPSs with catalytic domains bearing predicted amino acid specificity motifs (38)

Sequence analysis and deep annotation revealed that biosynthetic pathway architecture is non-collinear (as with SafA-B) and is represented by EtuA3→EtuA1→EtuA2. Indeed, other pathway similarities are evident relative to the saframycin and safracin systems, including the architecture of the key NRPS modules central to the cluster with flanking open reading frames transcribed in both forward and reverse directions. The exact arrangement of other genes in the cluster is not fully conserved between these tetrahydroisoquinoline biosynthetic pathways. For example, the genes encoding tyrosine modification are closely linked in the safracin gene cluster, but dispersed along the cluster in ET-743 and saframycin.

EtuA3 (AL-T-C-A-T) contains the AL-T starter module that is common to the saframycin, and saframycin Mx1 metabolic systems. The role of this module was elucidated for the saframycin biosynthetic pathway, where acylation of the precursor is required for further chain extension, cyclization and RE processing (e. g., Pictet-Spenglerase) (25). The NRPS A-domain, based upon the amino acid specificity motif, was predicted to utilize cysteine (DLYNLSI, Table S6) with 100% sequence identity to the top three cysteine A domain sequence motifs. EtuA3 specificity is, therefore, unique to the Etu biosynthetic pathway and represents a unique feature compared to other characterized tetrahydroisoquinoline systems that all utilize alanine (DLFNNALT, Table S6). EtuA1 (C-A-T) has the greatest homology to SafA module 1 by BLASTx; however, the protein sequence identity and similarity are relatively low (29/54) compared to the other NRPSs in the pathway. An A-domain selectivity motif cannot be identified in EtuA1. Based on structural analysis of ET-743, a glycolic acid unit is likely loaded and activated by the EtuA1 A-domain. Loading of hydroxy acids and formation of esters by NRPS modules have been characterized previously (39, 40). This extender unit represents another key difference compared to characterized tetrahydroisoquinoline antibiotics, for which a conserved core motif (7/8 amino acid identity) is both predicted and observed to select glycine (Table S6). EtuA2 (C-A-T-RE) contains the same A-domain specificity motif (DPWGLGLI, Table S6) for the final NRPS module as all known tetrahydroisoquinoline biosynthetic pathways. As verified in the saframycin biosynthetic system (25), the EtuA2 homolog SfmC iteratively extends two 3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr residues. The terminal EtuR2 RE domain serves as a key marker of the pathway and was examined biochemically to assess its activity in elaborating the tetrahydroisoquinoline core molecule (see below).

Non-NRPS biosynthetic genes

Pathway components that mediate production of essential cofactors or substrates are often encoded within biosynthetic gene clusters (23). EtuF1 and EtuF2 appear to represent subunits of an acetyl-CoA carboxylase. These enzymes transform acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA for fatty acid biosynthesis, and may supply substrate for synthesis of the fatty acid for EtuA3 AL. EtuF3 appears to be a penicillin acylase (41). We propose that this key enzyme may act to release the predicted fatty acid modified intermediate of ET-743 after formation of the tetradepsipeptide and Pictet-Spengler cyclization (Figure 4) prior to further processing into mature intermediates that are isolable from the tunicate. ET-743 is derived from at least two units of the unusual amino acid 3-hydroxy-4-O-methyl-5-methyl-tyrosine (3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr). The intermediate may be generated through 3-hydroxylation, 4-O-methylation, and 5-methylation of tyrosine. EtuH, an SfmD homolog, is predicted to hydroxylate tyrosine at the 3-position, whereas EtuM1, a SacF homolog, may be a SAM-dependent methyltransferase and a candidate for C-methylation at the 5-position. SafC, an EtuM2 homolog, has been characterized in vitro as a catechol 4-O-methyltransferase (42). Biochemical studies in the saframycin pathway revealed that SfmD (EtuH homolog), SfmM2 (EtuM1 homolog) and SmfM3 (EtuM2 homolog) form a minimal unit for 3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr production from tyrosine (43). EtuO is an FAD-dependent monooxygenase that shows high similarity to SfmO2 and SacJ. EtuO may catalyze modification of the tetrahydroisoquinoline to produce the hydroxylated species based on previous work involving sacJ gene disruption (Figure 4, 17–18) (22). In vitro biochemical characterization of this enzyme will require synthesis of an advanced biosynthetic intermediate to determine its precise activity.

Genes products of involved in regulation, resistance, and unknown function

EtuT shows high similarity to drug transport proteins. Members of this superfamily are commonly present in natural product biosynthetic pathways and could serve as part of a resistance/export mechanism for ET-743 (44). DNA processing enzymes such as EtuD1-3 are atypical in natural product biosynthetic pathways. We hypothesize that EtuD1-3 may have a role in repairing damage induced by ET-743 given its mechanism of action. EtuD1 appears to be a homolog of the TatD Mg2+ dependent DNAse (45) while EtuD2 shows similarity to a DNA polymerase III subunit δ', which has been characterized as part of the DNA-enzyme assembly complex. EtuD3 is a homolog of the 5'→3' exonuclease domain from DNA polymerase I. Three possible regulatory gene products EtuR1–3 have been identified in the biosynthetic pathway. EtuR1 has significant similarity (59%) to S29×, a protein previously shown to have a role in host-symbiont interactions between Amoeba proteus and the symbiotic Gram-negative “X-bacteria” (46). This fascinating protein is excreted from the bacterium, and localized to the A. proteus nucleus (47). The role of S29x in host-symbiont interactions is unclear with no other homologs characterized. The presence of a homolog to a characterized symbiont-derived gene in the Etu cluster suggests that regulated host-symbiont interactions may be involved in ET-743 biosynthesis. BLASTx analysis of EtuR2 shows (34/58%) identity/similarity to a MerR family transcriptional regulator. This class of regulators has been found in diverse classes of bacteria and responds to toxic effectors including heavy metals and antibiotics (48). EtuR3 resembles the TraR/DksA transcriptional regulator that functions as a DnaK suppressor protein. Three gene products in the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway could not be easily assigned to a possible role in the biosynthetic pathway. EtuU1 is related to a putative EtuP peptidase modulator of DNA gyrase, whereas EtuU2 appears to be a shikimate kinase I. EtuU3 is an unknown hypothetical protein. EtuN1, EtuN2, and EtuN3 appear to encode the three subunits of a Glu-tRNAGln amidotransferase (49). This enzyme forms correctly acylated Gln-tRNAGln by transamidation of aberrant Glu-tRNAGln. The role of these genes in the ET-743 pathway is unknown. EtuP1 and EtuP2 form two components (E1 and E2) of a possible pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, which catalyzes the transformation of pyruvate into acetate, but its function remains unclear in the Etu pathway. Other genes may be missing from the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway, for example, homologues of the proposed SAM recycling system, and a putative N-methyl transferase in the saframycin biosynthetic pathway have not been identified (23).

Proposed scheme for ET-743 biosynthesis

Our proposed scheme begins with assembly of the key subunit 3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr (7) (Figure 4). This non-proteinogenic amino acid is likely formed by 3-hydroxylation of (4), 4-O methylation of (5), and 5-methylation (6) catalyzed by EtuH, EtuM2, and EtuM1 (43), respectively. Next, the fatty acid CoA ligase of EtuA3 loads a fatty acid (8) onto the T domain. We presume that cysteine is N-acylated and loaded by the C-A-T module of EtuA3 (9). Cysteine condenses with a T-loaded glycolate on EtuA1 to form the acylated-depsipeptide (10). Based on Koketsu's model (25), (10) is reductively released by the EtuA2 RE-domain as an aldehydo-depsipeptide (11) from the EtuA1 T-domain. Such a terminal domain "reach-back" model has been previously reported in natural product biosynthesis (50). EtuA2 loaded with 3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr (7) is then condensed with (11) to form the cyclic aldehyde-tridepsipeptide (12) through the presumed Pictet-Spenglerase activity of the EtuA2 C domain. Intermediate (12) is released from the EtuA2 T by the RE-domain activity as an aldehyde (13). In concert with Koketsu's model it is proposed that EtuA2 catalyzes a second Pictet-Spengler reaction between another unit of 3H-4O-Me-5Me-Tyr (7) and (13). The protein-bound tetradepsipeptide (14) is then reductively released to form aldehyde (15) that may undergo a further enzyme-catalyzed Pictet-Spengler reaction to form the fatty-acid bound carbinolamine pre-ET-743 (16). The penicillin acylase EtuF3 (16) is then proposed to cleave the fatty acid unit, which may serve to sequester substrate in the EtuA2 active site during repeated loading/release, forming pre-ET-743 (17). Proposed intermediates ET-583 (18), ET-597 (19), ET-596 (20), and ET-594 (21) have all been isolated, characterized (32), and all except ET-596 (20) have been confirmed by our secondary metabolite analysis (Figure S3). We propose that pre-ET-743 (17) is hydroxylated by EtuO, acetylation and formation of the thioether ring are both catalyzed by unknown enzymes/mechanisms and intermediates to form ET-583 (18). An unidentified N-methyltransferase acts on ET-583 (18) to generate ET-597 (19). In accordance with Sakai, we propose that a transamination reaction proceeds on (19) to produce ET-596 (20). Another unknown protein catalyzes formation of a methylene dioxybridge in the A ring to generate ET-594 (21). Since compounds (18 – 21) are isolable, and tryptophan analogs of ET-743 have also been observed (32), it is reasonable to propose that the final subunit to complete biosynthesis of the drug is added at a late stage, perhaps by formation of an imine to the β-carbonyl and the new tyrosine analog. In both ET-743 total synthesis and semi-synthesis schemes, the α-ketone (21) is transformed to the final tetrahydroisoquinoline ring system by addition of 4-O-methyl-tyrosine under mild conditions (8, 10). Further processing steps are hypothetical, with neither enzyme nor intermediate identified. We propose that another tyrosine analog, 4-O-methyl-tyrosine (22) is condensed with ET-594 (21). The proposed imine intermediate (24) may then undergo another Pictet-Spengler-type reaction to form the final ring system (25). It is unknown if this unusual cyclization reaction and reduction is catalyzed by EtuA2 or an additional enzyme. The mechanism by which the proposed thioester of ET-743 is released from the proposed enzyme as ET-743 (1) remains to be established. Rigorous validation of this proposed pathway will require synthesis of the predicted enzyme substrates, and direct biochemical analysis with the full spectrum of enzymes now available through identification of this biosynthetic system.

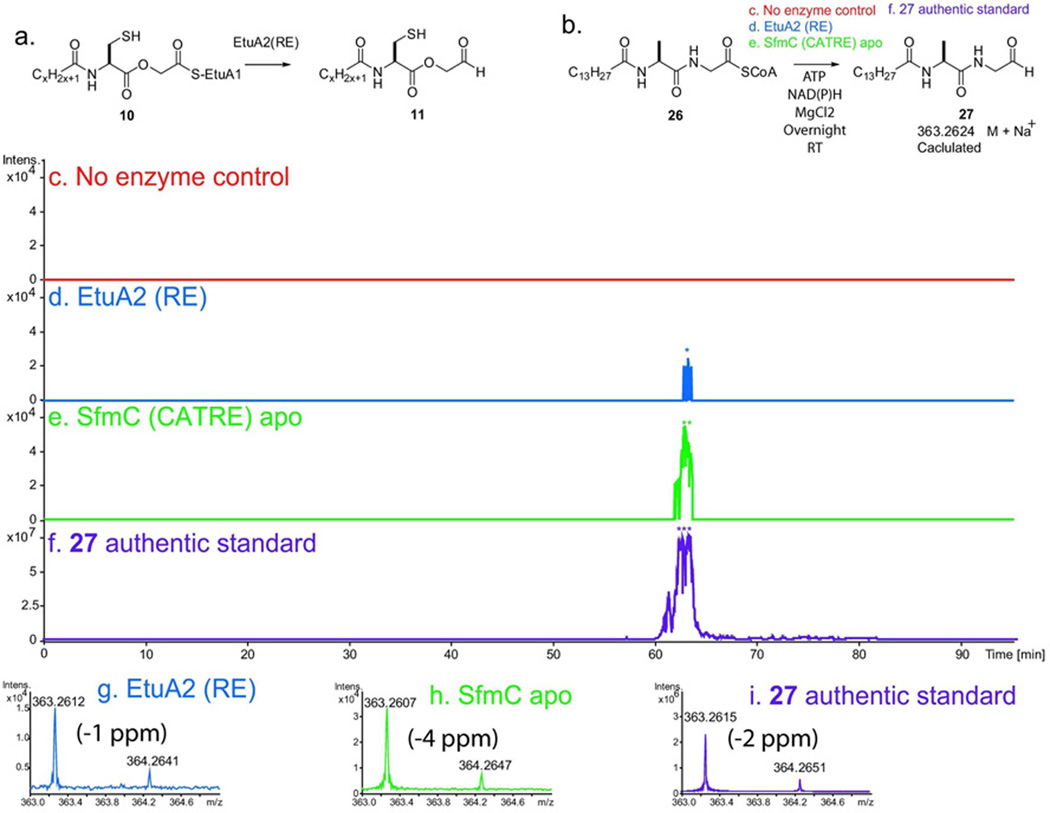

Confirmation of enzymatic activity for the ET-743 NRPS termination domain

The transformation of thioester-bound acylated-depsipeptide (10) to the aldehyde-didepsipeptide (11) is a key enzymatic step thought to be catalyzed by the EtuA2 RE domain. We, therefore, cloned and overexpressed the excised EtuA2 RE domain to test this activity (Figure S1). Koketsu and coworkers demonstrated this reductive termination activity for the corresponding saframycin substrate analogs (26 → 27) with the SfmC A-T-RE-tridomain (25). The saframycin substrate analog (26) previously prepared by Koketsu was synthesized and transformed into the saframycin aldehyde-dipeptide (27) by the EtuA2 RE domain (Figure 5). As a positive control, substrate (26) was converted with high efficiency to (27) by purified apo-SfmC (C-A-T-RE). The differential activity was expected as (26), while clearly an acceptable substrate, lacks the cysteine-derived thiol with a glycine in place of the glycolic acid compared to the native substrate (10). Enzyme reaction products were in complete agreement with an authentic standard (27). Development of a synthetic scheme to generate compounds (10–11) for analysis of RE enzyme activity with the fully native substrate is currently in progress. Confirmation of RE enzyme activity links our predicted biochemical scheme to demonstrated function in the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway.

Figure 5.

EtuA2 RE and SfmC reactions with (26). a) The proposed biochemical activity of EtuA2 RE-domain in transforming activated didepsipeptide acyl-thioester (10) to the aldehyde (11). b) The analogous reaction for SfmC is the transformation of (26) to (27) as reported by Koketsu (25). The reaction of (26) to (27) was investigated with no enzyme control (c), EtuA2 RE-domain (d), SfmC (e), and an authentic standard of (27) (f). The aldehyde-dipeptide product (27) was monitored as the Na+ adduct in positive ion mode by LC-FTICR MS with an EIC at +/−20 ppm. Inset spectra are shown over the peak elution window (g–i).

Metaproteomics to identify ET-743 biosynthetic proteins

Total tryptic peptides from the field-collected E. turbinata sample were fractionated by strong-cation-exchange chromatography, desalted, and then analyzed by reversed-phase nano-LC MS/MS. Datasets were collected on LTQ-Orbitrap and 12T Q-FTICR mass spectrometers, with high-resolution/mass-accuracy MS1 spectra (and MS2 for FTICR). Data were processed in Trans Proteomic Pipeline (51) with four distinct search engines (X!tandem, OMSSA, Inspect, and Spectrast) and the Peptide and Protein Prophet probability models with false discovery rates at the protein level of 0.6–0.9%. The database searched consisted of a six-frame translation of the total metagenome assembly filtered to contain all possible polypeptides >60 amino acids in length. Sequence length-based cutoffs were utilized rather than ORF prediction due to the short length of many metagenomic contigs derived from the 454 sequencing. Filtering resulted in a six-fold reduction in total sequence length versus the unfiltered six-frame translation. A 60 amino acid cut-off represents a 0.2% chance of any random sequence producing a translation without a stop codon appearing. Based upon 23S/16S rRNA gene sequences, the closest fully sequenced organisms to the four principle constituents of the assemblage were included to assign homologous proteins derived from genes that may have been incompletely sequenced in the metagenomic analysis (tunicate: Ciona intestinalis NZ_AABS00000000, α-proteobacteria: Ruegeria pomeroyi DSS-3 NC_003911, γ-proteobacteria: Coxiella burnetii RSA 331 NC_010115, unknown bacteria: Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC str. PG1 NC_005364). Reversed sequences for all proteins were included as decoys in the search database.

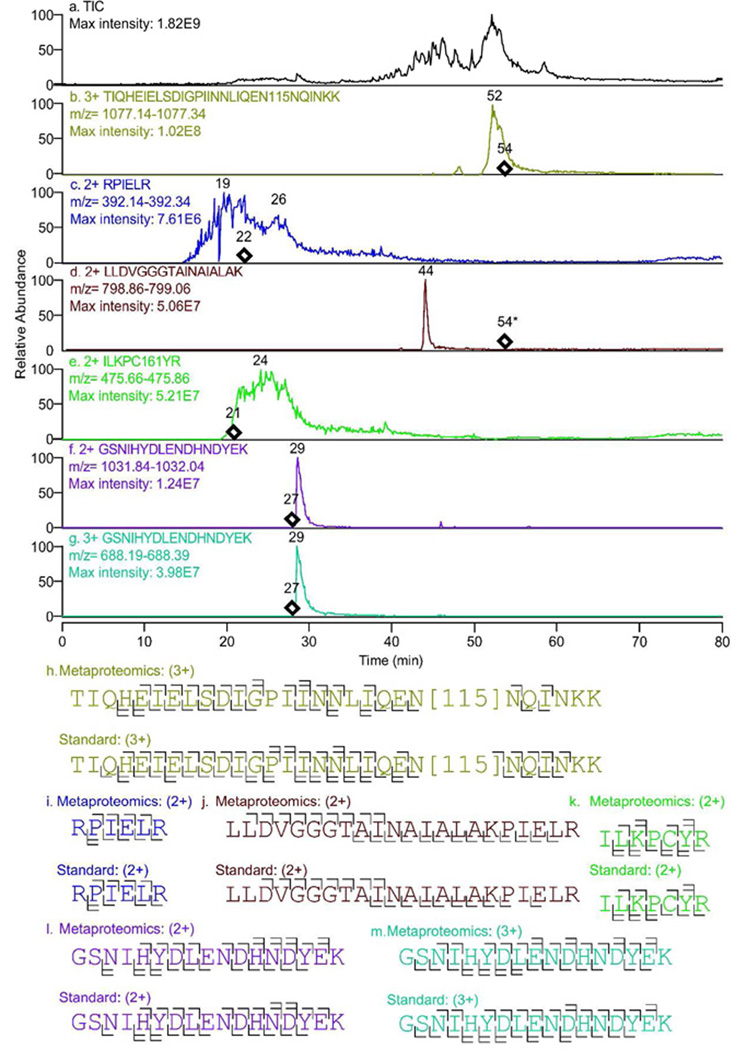

A total of 289 proteins were identified at a probability >95% from Interprophet pooled analysis of all four search engines prior to Protein Prophet analysis (Table S8–9). Three of the proteins identified were derived from the Etu pathway with two identified by Orbitrap and one by FTICR and Orbitrap MS. The penicillin acylase EtuF3 was identified with two unique peptides, 3+ TIQHEIELSDIGPIINNLIQEN115NQINKK (N115=deamidated) and 2+ RPIELR, and the protein was identified in 3/4 search engines providing a total protein probability of 99.99%. The bacterial symbiont protein EtuR1 was identified with two unique peptides, 2+ GSNIHYDLENDHNDYEK and 3+ GSNIHYDLENDHNDYEK, identified by 3/4 search engines at the protein level with a combined protein probability of 100.00% The EtuM1 SAM dependent methyltransferase was identified by one unique peptide, 2+ LLDVGGGTAINAIALAK and 2/4 search engines at the protein level with a probability of 99.16% (Tables S9–16). Identified Etu peptides were validated by comparison with synthetic peptide standards by LC elution time (±2 minutes on the same nano-LC system), and MS/MS fragmentation spectra (Fig 6). This synthetic peptide data strongly supports all Etu peptide and protein assignments from the metaproteomics dataset. Detailed spectral information is provided (Table S20–25, Figure S5–24, Tranche Proteome Commons). These three biosynthetic pathway proteins identified by multiple search algorithms and comparison with authentic standards suggests that ET-743 biosynthetic genes are expressed in the tunicate microbial symbiont assemblage.

Figure 6.

Synthetic peptides as authentic standards to verify metaproteomics peptide assignments. a) Total ion chromatogram for the standard peptide mixture on the LTQ-orbitrap. b–g) extracted ion chromatograms generated at +/− 0.1 m/z for each of the synthetic peptides in the mixture. Chromatograms are presented as time versus normalized intensity. Maximum intensity in each normalized total or extracted ion chromatogram is noted. *Denotes that the experimental retention time for doubly protonated tryptic LLDVGGGTAINAIALAK was obtained on a different LC system with a different gradient and column, as compared to the authentic standard. In the case of all other synthetic standard versus experimental identifications the LC system and gradient were identical, although a different column was used. ◊ denotes the elution time of the experimental MS2 spectra assigned to each of the peptides. Peptide MS2 sequence coverage for metaproteomics versus authentic standard synthetic peptides (h–m). Only b and y ion assignments are shown although other ions (e.g., a, b - H2O, b - NH3, y - H2O, and y - NH3) could also be assigned. Multiple bars indicate that a given fragment can be assigned to multiple charge states.

Metagenomic and metaproteomic technologies enable powerful new approaches to gene, genome, protein and metabolic pathway discovery. Access to next-generation sequencing and development of bioinformatics tools is essential for deconvolution of the enormous databases generated from these technology applications. This study was motivated by the opportunity to identify and characterize an enormous range of host-symbiont derived natural product systems that have remained refractory to analysis. The inability to culture the vast majority of bacterial and fungal symbionts (outside of their natural host or environmental niche) that produce secondary metabolites have limited our access to a huge genetic diversity relating to untapped chemical resources for therapeutic and other industrial applications. This includes complex marine (e.g., sponge, tunicates, dinoflagellates) and terrestrial (e.g., plant-microbe, biofilm, insect-gut, human-gut) microbial consortia where the presence of large populations of diverse microorganisms and their corresponding genomes that bear natural product gene clusters remain unexplored. This new source of metabolic and chemical diversity will lead to important new basic knowledge, and also contribute to on-going drug discovery efforts against many disease indications. In order to initiate this meta-omic analysis, ET-743 was chosen as a model system due to the predicted genetic composition of core components of its biosynthetic pathway. This was based on the assumption of a highly conserved overall architecture from previously characterized pure culture bacterial-derived metabolic pathways for related tetrahydroisoquinoline natural products (11, 12, 13). Moreover, recent advances in next-generation sequencing and bioinformatic tools to assemble contigs from large metagenomic datasets, and analysis of proteomic data to identify low-abundance proteins enabled the approaches described in this report. Although our model system choice was driven by the attributes of the ET-743 system (e.g. potent medicinal properties, complex structural and biosynthetic features), our overall strategy is not limited to symbiont-derived metabolic pathways that generate known natural products. In the future we anticipate that deep metagenomic sequencing will provide access to fully assemble genomes (1) from uncharacterized DNA samples. Bioinformatic prediction of candidate secondary metabolic pathways (52) and structures (53) followed by MSn based network dereplication could then allow identification of the encoded natural product(s). Concurrent efforts can include proteomic analysis to confirm biosynthetic enzyme production (54). Finally, with fully assembled secondary metabolite pathways discovered from these approaches, heterologous expression and metabolic pathway engineering will then play a central role in harnessing the pathways to generate suitable quantities of molecules for drug discovery efforts.

In these studies, several approaches were taken to obtain evidence for identification of the ET-743 biosynthetic pathway and the corresponding producing microbial symbiont. First, the presence of the ET-743 natural product and intermediates were used as markers for the producing bacterium in the tunicate/microbial consortium. Second, codon usage similarity between the biosynthetic gene cluster and a contig containing a 16S rRNA gene sequence are consistent with E. frumentensis as the bacterial producer of ET-743. Direct functional analysis of a key biosynthetic enzyme confirmed its predicted catalytic assignment in the pathway. Finally, symbiont-derived expression of three ET-743 biosynthetic enzymes was confirmed by metaproteomic and bioinformatic analysis, enabling the direct correlation between natural product, the Etu gene cluster, and predicted biosynthetic proteins. This tiered strategy provides a general approach for future efforts to characterize orphan and target natural product biosynthetic systems from complex marine and terrestrial microbial assemblages including invertebrate-microbial symbionts, biofilm mats, and mammalian and insect gut consortia. The ET-743 biosynthetic system was selected as a model for this technological platform due to its importance as an approved chemotherapeutic agent.

The initial characterization of 25 putative ET-743 biosynthetic proteins will enable future efforts to confirm the function of individual enzymes by direct biochemical analysis. These in vitro findings will drive future efforts to engineer production of the ET-743 drug and related analogs. This work also provides the first key step toward supplying ET-743 and new congeners through heterologous expression in an amenable production host.

METHODS

Supporting Information for detailed descriptions of experimental methodology.

E. turbinata sample collection

Tunicate specimens were collected in the Florida Keys, frozen on dry ice, and shipped overnight. See supplemental information for further details.

Secondary metabolite identification by LC-FTICR-MS and confirmation by LC-MS/MS

Tunicate samples were deproteinized with MeOH, the protein was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was concentrated and analyzed on a C18 column. FTICR MS was performed on an APEX-Q by ESI in positive ion mode. A comprehensive peak list of possible ET-743 related metabolites was used for precursor ion selection. Data were processed in Data Analysis and MS/MS spectra were interpreted manually. Metabolite peaks were detected over multiple samples and runs. Iontrap-MS/MS was performed as above and with an LTQ Deca XP Ion trap MS. Data analysis was performed in Excalibur and MS/MS spectra were interpreted manually.

454 and 16S rRNA gene library construction and sequencing methods

Metagenomic DNA was extracted from frozen E. turbinata samples. DNA was used to prepare a 16S rRNA gene targeted amplicon library using primers and a random shotgun 454 FLX library. Sequencing was performed on a Roche/454 Life Sciences FLX Sequencer. A second shotgun library was prepared using the 454 Titanium upgrade.

NRPS module identification

Reads/contigs were filtered by protein homology to the saframycin, saframycin Mx1, and safracin NRPS genes characterized in S. lavendulae (DQ838002), M. xanthus (U24657), and P. fluorescens (AY061859) using BLASTx/tBLASTn searches. Primers were designed from the ends of filtered sequences, and PCR reactions were conducted based on the location of the BLAST hit on the reference sequences. Positive amplification reactions lead to extension of the contigs and further sequencing revealed the intervening DNA. Flanking sequence from high interest contigs was obtained by restriction-site PCR (RS-PCR).

Analysis of the E. turbinate microbial consortium by metagenomic sequence analysis

Classification of the raw reads and total assembly was performed with MG-RAST. Sequences were classified by protein homology to a manually curated database. The 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence data was analyzed by assembling the raw reads. The assembled contigs were submitted to the RDP. Gene-finding was performed on the NRPS contig, E. frumentensis 16S contig (contig00422), and random contigs from the total shotgun assembly.

EtuA2-RE and SfmC cloning and expression

The sfmC gene was amplified using genomic DNA of Streptomyces lavendulae NRRL 11002 as template. The PCR product was digested and cloned into pET-28a to generate pET28a-sfmC. The RE fragment was amplified via PCR using the metagenomic DNA mixture as template, digested, and cloned into pET-28a, to generate pET28a-RE. The N-His-Tagged expression constructs were separately transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) +pRare and expressed and purified under standard conditions using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography.

Synthesis of substrate (26 and 27) for EtuA2 RE reactions

Biochemical reaction of EtuA2 RE-domain and SfmC with the CoA dipeptide fatty acid (26)

The biochemical reaction of compound (26) to (27) was performed as described previously (25). Reactions took place in buffer with either no enzyme, EtuA RE-domain, or SfmC. Cofactors were then added from concentrated stocks. Compound (26) was then added in DMF followed by incubation overnight at room temperature. LC-FTICR MS was performed to monitor the reaction products.

Metaproteomic analysis of ET-743 biosynthetic gene expression

Tunicate protein samples were precipitated with acetone then resolubilized, reduced, alkylated, diluted, and digested with trypsin. The sample was separated into 20 fractions using SCX chromatography. The 20 peptide fractions were analyzed once on an LTQ-Orbitrap XL interfaced with a nanoLC 2D system. Peptides were separated on a capillary column in-house packed with C18 resin after loading on a C18 trap column. LC eluent was introduced into the instrument via a chip-based nanoelectrospray source in positive ion mode. The LTQ-orbitrap was operated in data-dependent mode. The 20 peptide fractions were also analyzed in duplicate on a Solarix 12T hybrid Q-FTICR interfaced with a nanoLC system. Peptides were separated on a capillary column packed in-house with C18 resin after loading on a C18 trap column. The FTICR operated in data-dependent mode. All scans were collected in the profile mode and peak picking was performed from the profile mode spectra. Bioinformatics analysis was performed with the Transproteomic Pipeline and all assigned Etu peptides were validated by comparison with synthetic peptide standards.

Accession Codes

Sequence data have been deposited in Genbank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank (Accession numbers HQ542106 and HQ609499). The proteomics dataset has been deposited in Tranche Proteomic commons: (https://proteomecommons.org/dataset.jsp?i=FOIwaTzxhqbiEK1DShCVR4shblJ4c%2BAR%2BKAKY3c5fBd7uFYC6Ti6pdjvPxSPK2VgaSHDTEzDPeu%2FyshMZLe9qMe2gooAAAAAAACkEg%3D%3D)with the password: tunicate_et

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Erich Bartels, Vicki Woodbridge, and Mote Marine Laboratories for assistance with sample collection, and Kate Noon at the UM Department of Pharmacology Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with IT-MS. Bruker Daltonics is gratefully acknowledged for access to the 12T FTICR-MS, and Philip Andrews for access to the Orbitrap-MS (supported by NCRR-P41) used in this study. We thank Damian Fermin of the Nesvizhskii laboratory for help with the TPP, and George Chlipala for assistance with Perl scripts. Work was supported by NIH Grant CA070375 (R.M.W. and D.H.S), the H. W. Vahlteich Professorship (D.H.S), a Microfluidics in Biomedical Sciences Training Grant fellowship (C.M.R.), and the Allegheny Singer Research Foundation and DHHS/HRSA C76HF00659 (G.D.E). This work was also inspired by NIH grant U01 TW007404 as part of the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group initiative at the Fogarty International Center.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Detailed methods, additional figures, tables, and discussion are presented in the supplement. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Author Contributions. C.M.R, and B.J. contributed equally to this work; C.M.R., B.J., F.Z.H, K.H., R.M.W., G.D.E., and D.H.S. designed research; C.M.R., B.J., J.E., A.A., F.Z.H., L.H., M.D., R.K., F.Y., J.W., H.K., and M.C. performed the experiments; C.M.R., B.J., K.H., G.D.E, and D.H.S analyzed data; C.M.R., B.J., K.H., G.D.E. and D.H.S. wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Hess M, Sczyrba A, Egan R, Kim T-W, Chokhawala H, Schroth G, Luo S, Clark DS, Chen F, Zhang T, Mackie RI, Pennacchio LA, Tringe SG, Visel A, Woyke T, Wang Z, Rubin EM. Metagenomic discovery of biomass-degrading genes and genomes from cow rumen. Science. 2011;331:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1200387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinehart KL, Holt TG, Fregeau NL, Stroh JG, Keifer PA, Sun F, Li LH, Martin DG. Ecteinascidins 729, 743, 745, 759A, 759B, and 770: potent antitumor agents from the Caribbean tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:4512–4515. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izbicka E, Lawrence R, Raymond E, Eckhardt G, Faircloth G, Jimeno J, Clark G, Von Hoff DD. In vitro antitumor activity of the novel marine agent, ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743, NSC-648766) against human tumors explanted from patients. Annals Oncol. 1998;9:981–987. doi: 10.1023/A:1008224322396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minuzzo M, Marchini S, Broggini M, Faircloth G, D'Incalci M, Mantovani R. Interference of transcriptional activation by the antineoplastic drug ecteinascidin-743. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6780–6784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pommier Y, Kohlhagen G, Bailly C, Waring M, Mazumder A, Kohn KW. DNA sequence- and structure-selective alkylation of guanine N2 in the DNA minor groove by Ecteinascidin 743, a potent antitumor compound from the Caribbean tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. Biochem. 1996;35:13303–13309. doi: 10.1021/bi960306b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takebayashi Y, Pourquier P, Zimonjic DB, Nakayama K, Emmert S, Ueda T, Urasaki Y, Kanzaki A, Akiyama S-I, Popescu N, Kraemer KH, Pommier Y. Antiproliferative activity of ecteinascidin 743 is dependent upon transcription-coupled nucleotide-excision repair. Nat. Med. 2001;7:961–966. doi: 10.1038/91008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carballo JL, Naranho S, Kukurtzu B, De La Calle F, Hernandez-Zanuy A. Production of Ecteinascidia turbinata (Ascidiacea: Perophoridae) for obtaining anticancer compounds. J. World Aquaculture Soc. 2000;31:481–490. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corey EJ, Gin DY, Kania RS. Enantioselective total synthesis of Ecteinascidin 743. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:9202–9203. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuevas C, Francesch A. Development of Yondelis (trabectedin, ET-743). A semisynthetic process solves the supply problem. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:322–336. doi: 10.1039/b808331m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuevas C, Pérez M, Martín MJ, Chicharro JL, Fernández-Rivas C, Flores M, Francesch A, Gallego P, Zarzuelo M, Calle F, García J, Polanco C, Rodríguez I, Manzanares I. Synthesis of ecteinascidin ET-743 and phthalascidin Pt-650 from cyanosafracin B. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2545–2548. doi: 10.1021/ol0062502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai T, Takahashi K, Nakahara S, Kubo A. The structure of a novel antitumor antibiotic, saframycin A. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1980;36:1025–1027. doi: 10.1007/BF01965946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irschik H, Trowitzschi-Kienast W, Gerth K, Hofle G, Reichenbach H. Saframycin Mx1, a new natural saframycin isolated from a myxobacterium. J. Antibiotics. 1988;41:993–998. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda Y, Shimada Y, Honjo K, Okumoto T, Munakata T. Safracins, new antitumor antibiotics. J. Antibiotics. 1983;36:1290–1294. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piel J. Bacterial symbionts: prospects for the sustainable production of invertebrate-derived pharmaceuticals. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006;13:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudek S, Lopanik NB, Waggoner LE, Hildebrand M, Anderson C, Liu H, Patel A, Sherman DH, Haygood MG. Identification of the putative bryostatin polyketide synthase gene cluster from "Candidatus Endobugula sertula", the uncultivated microbial symbiont of the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:67–74. doi: 10.1021/np060361d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopanik NB, Shields JA, Buchholz TJ, Rath CM, Hothersall J, Haygood MJ, Hakansson K, Thomas CM, Sherman DH. In vivo and in vitro trans-acylation by BryP, the putative bryostatin pathway acyltransferase derived from an uncultured marine symbiont. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1175–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piel J. A polyketide synthase-peptide synthetase gene cluster from an uncultured bacterial symbiont of Paederus beetles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14002–14007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222481399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piel J, Hui D, Wen G, Butzke D, Platzer M, Fusetani N, Matsunaga S. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16222–16227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405976101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisch KM, Gurgui C, Heycke N, van der Sar SA, Anderson SA, Webb VL, Taudien S, Platzer M, Rubio BK, Robinson SJ, Crews P, Piel J. Polyketide assembly lines of uncultivated sponge symbionts from structure-based gene targeting. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:494–501. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt EW, Nelson JT, Rasko DA, Sudek S, Eisen JA, Haygood MG, Ravel J. Patellamide A and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Procholoron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc. Nat. Acad. USA. 2005;102:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501424102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donia MS, Ravel J, Schmidt EW. A global assembly line for cyanobactins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:341–343. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velasco A, Acebo P, Gomez A, Schleissner C, Rodríguez P, Aparicio T, Conde S, Muñoz R, De La Calle F, Garcia JL, Sánchez-Puelles JM. Molecular characterization of the safracin biosynthetic pathway from Pseudomonas fluorescens A 2-2: designing new cytotoxic compounds. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:144–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Deng W, Song J, Ding W, Zhao Q-F, Peng C, Song W-W, Tang G-L, Liu W. Characterization of the saframycin A gene cluster from Streptomyces lavendulae NRRL 11002 revealing a nonribosomal peptide synthetase system for assembling the unusual tetrapeptidyl skeleton in an iterative manner. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:251–263. doi: 10.1128/JB.00826-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pospiech AC, B Bietenhader J, Schupp T. A new Myxococcus xanthus gene cluster for the biosynthesis of the antibiotic saframycin Mx1 encoding a peptide synthetase. Microbiol. 1995;141:1793–1803. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-8-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koketsu K, Watanabe K, Suda H, Oguri H, Oikawa H. Reconstruction of the saframycin core scaffold defines dual Pictet-Spengler mechanisms. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:408–411. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss C, Green DH, Perez B, Valasco A, Henriquez R, Mckenzie JD. Intracellular bacteria associated with the ascidian Ecteinascidia turbinata: phylogenetic and in situ hybridisation analysis. Mar. Biol. 2003;143:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parez-Matos AE, Rosado W, Govind NS. Bacterial diversity associated with the Caribbean tunicate Ecteinascidia turbinata. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2007;92:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s10482-007-9143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrlich G, Hiller NL, Hu F. What makes pathogens pathogenic. GenomeBiology.com. 2008;9:225–225. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilmes P, Bond PL. Metaproteomics: studying functional gene expression in microbial ecosystems. Trends in Microbiol. 2006;14:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ro D-K, Paradise EM, Ouellet M, Fisher KJ, Newman KL, Ndungu JM, Ho KA, Eachus RA, Ham TS, Kirby J, Chang MCY, Withers ST, Shiba Y, Sarpong R, Keasling JD. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel SC, Muller R. Recent developments towards the heterologous expression of complex bacterial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Cur. Op. Biotech. 2005;16:594–606. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakai R, Jares-Erijman EA, Manzanares I, Silva Elipe MV, Rinehart KL. Ecteinascidins: putative biosynthetic precursors and absolute stereochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:9017–9023. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ragin CCR, Reshmi SC, Gollin SM. Mapping and analysis of HPV16 integration sites in a head and neck cancer cell line. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;110:701–709. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer F, Paarmann D, D'Souza M, Olson R, Glass EM, Kubal M, Paczian T, Rodriguez A, Stevens R, Wilke A, Wilkening J, Edwards RA. The metagenomics RAST serve: a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:386–394. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharp KH, Davidson SK, Haygood MG. Localization of ‘Candidatus Endobugula sertula’ and the bryostatins throughout the life cycle of the bryozoan Bugula neritina. ISME J. 2007;1:693–702. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dehal P, et al. The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science. 2002;298:2157–2167. doi: 10.1126/science.1080049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto S, He Y, Arakawa K, Kinashi H. Gamma-butyrolactone-dependent expression of the Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein gene srrY plays a central role in the regulatory cascade leading to lankacidin and lankamycin production in Streptomyces rochei. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:1308–1316. doi: 10.1128/JB.01383-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachmann BO, Ravel J. Chapter 8 methods for in silico prediction of microbial polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthetic pathways from DNA sequence data. Meth. Enzymology. 2009;458:181–217. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magarvey NA, Ehling-Schulz M, Walsh CT. Characterization of the cereulide NRPS α-hydroxy acid specifying modules: activation of α-keto acids and chiral reduction on the assembly line. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10698–10699. doi: 10.1021/ja0640187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calderone CT, Bumpus SB, Kelleher NL, Walsh CT, Magarvey NA. A ketoreductase domain in the PksJ protein of the bacillaene assembly line carries out both alpha and beta-ketone reduction during chain growth. Proc. Nat. Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12809–12814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806305105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arroyo M, Mata I, Acebal C, Castillion MP. Biotechnological applications of penicillin acylases: state-of-the-art. Ap. Microbiol. Biotech. 2003;60:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson JT, Lee J, Sims JW, Schmidt EW. Characterization of SafC, a catechol 4-O-methyltransferase involved in saframycin biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:3575–3580. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00011-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu C-Y, Tang M-C, Chao P, Lei L, He Y-L, Wen L, Tang GL. Biosynthesis of 3-hydroxy-5-methyl-o-methyltyrosine in the saframycin/ safracin biosynthetic pathway. J. Microbiol. Biotech. 2009;19:439–446. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0808.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jack DL, Yang NMH, Saier M. The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:3620–3639. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wexler M, Sargent F, Jack RL, Stanley NR, Bogsch EG, Robinson C, Berks BC, Palmer T. TatD is a cytoplasmic protein with DNase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;275:16717–16722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pak J, Jeon KW. The s29× gene of symbiotic bacteria in Amoeba proteus with a novel promoter. Gene. 1996;171:89–93. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pak J, Jeon KW. A symbiont-produced protein and bacterial symbiosis in Amoeba proteus. J. Eurk. Microbiol. 1997;44:614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:145–163. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curnow AW, Hong K-W, Yuan R, Kim S-I, Martins O, Winkler W, Henkin TM, Söll D. Glu-tRNAGln amidotransferase: a novel heterotrimeric enzyme required for correct decoding of glutamine codons during translation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11819–11826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kittendorf JD, Beck BJ, Buchholz TJ, Seufert W, Sherman DH. Interrogating the molecular basis for multiple macrolactone ring formation by the pikromycin polyketide synthase. Chem Biol. 2007;14:944–954. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deutsch EW, Mendoza L, Shteynberg D, Farrah T, Lam H, Tasman N, Sun Z, Nilsson E, Pratt B, Prazen B, Eng JK, Martin DB, Nesvizhskii AI, Aebersold R. A guided tour of the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline. Proteomics. 2010;10:1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nuc. Acid. Res. 2011;39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li MHT, Ung PMU, Zajkowski J, Sylvie Garneau-Tsodikova S, Sherman DH. Automated genome mining for natural products. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:185. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bumpus SB, Evans BS, Thomas PM, Ntai I, Kelleher NL. A proteomics approach to discovering natural products and their biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Biotech. 2009;27:951–956. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.