Abstract

GPER/GPR30 is a seven-transmembrane G protein-coupled estrogen receptor that regulates many aspects of mammalian biology and physiology. We have previously described both a GPER-selective agonist G-1 and antagonist G15 based on a tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline scaffold. The antagonist lacks an ethanone moiety that likely forms important hydrogen bonds involved in receptor activation. Computational docking studies suggested that the lack of the ethanone substituent in G15 could minimize key steric conflicts, present in G-1, that limit binding within the ERα ligand binding pocket. In this report, we identify low-affinity cross-reactivity of the GPER antagonist G15 to the classical estrogen receptor ERα. To generate an antagonist with enhanced selectivity, we therefore synthesized an isosteric G-1 derivative, G36, containing an isopropyl moiety in place of the ethanone moiety. We demonstrate that G36 shows decreased binding and activation of ERα, while maintaining its antagonist profile towards GPER. G36 selectively inhibits estrogen-mediated activation of PI3K by GPER but not ERα. It also inhibits estrogen- and G-1-mediated calcium mobilization as well as ERK1/2 activation, with no effect on EGF-mediated ERK1/2 activation. Similar to G15, G36 inhibits estrogen- and G-1-stimulated proliferation of uterine epithelial cells in vivo. The identification of G36 as a GPER antagonist with improved ER counterselectivity represents a significant step towards the development of new highly selective therapeutics for cancer and other diseases.

1. Introduction

Estrogens mediate a range of physiological processes, including roles in reproduction, the immune, nervous and cardiovascular systems [1]. Additionally, estrogen signaling plays a role in breast, ovarian and other types of cancer [2]. Estrogen signaling is mediated through at least three receptors, including the soluble nuclear receptors ERα and ERβ, and GPER, a seven transmembrane-spanning G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) [3]. All three of these receptors can mediate gene transcription events, either directly, as in the case of ERα and ERβ [1], or indirectly, as in the case of GPER [4, 5]. ERα, ERβ and GPER can also mediate rapid signaling events through activation of MAPK, PI3K, Src kinase and related pathways [2, 3]. In vivo, these receptors vary in their tissue distribution and the estrogen responsiveness of a given tissue is determined both by receptor expression, co-regulator expression and by signaling interplay between receptors in response to estrogen [1, 3].

Estrogen receptors overlap in some physiological functions as well as in their ligand specificity. The triphenylethylene derivative tamoxifen is representative of the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) anti-estrogen class of therapeutics that inhibit the binding of the endogenous ligand, 17β-estradiol (E2, 1), to ERα and ERβ, while fulvestrant (faslodex, ICI182,780) represents the “pure” antiestrogen class of therapeutics that initiates ERα and ERβ receptor down-regulation. Paradoxically, both of these compounds act as GPER agonists [6, 7], and the resulting agonist/antagonist properties of these compounds vary by receptor status and/or tissue [8]. Thus, compounds with selectivity towards a single receptor are of great use for probing receptor function in complex systems where multiple estrogen receptors are expressed. We have previously developed a GPER-selective agonist, G-1 2 [9], and a GPER-selective antagonist, G15 3 [10], which have been used to elucidate GPER function in a variety of systems, both in vitro as well as in vivo. For example, G-1 has been used to define a role for GPER in proliferation [4, 11], protein kinase C activation [12], PI3K activation [9] and calcium mobilization in a range of cells [9, 13, 14]. Additionally, G-1 has been used in in vivo systems to investigate the roles of GPER in uterine epithelial proliferation [10], thymic atrophy [15], immune regulation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (a murine model of multiple sclerosis) [15, 16] and vascular regulation [17]. The antagonist G15 has now been used by several groups to establish the role of GPER in estrogen-mediated events, including vasodilation,[18] zebrafish oocyte maturation [19], neuroprotection [20] and inhibition of chondrogenesis [21]. These results indicate that selective ligands for GPER have a wide range of functional applications and can contribute to our understanding of the contributions of GPER signaling in complex systems expressing ERα and/or ERβ in addition to GPER.

Particularly in systems expressing multiple estrogen receptors, the utility of these compounds derives from and is limited by their selectivity for GPER versus ERα and ERβ. These small molecules are based on a common tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline scaffold, with the key difference between agonist G-1 and antagonist G15 being the presence of an ethanone moiety on G-1 [9, 10]. Since G15 lacks this bulky substituent group and, as we demonstrate here, exhibits increased ERα/β activity compared to G-1, we synthesized G36, a G-1 analog that contains an isopropyl moiety substituted for the ethanone in G-1. We postulated that the increased bulk present in G-1 and G36 would increase steric clashes within the binding pocket of ERα and ERβ compared to G15, thus limiting the binding and downstream signaling activity observed when high doses of G15 are used.

In this report, we describe the identification and characterization of G36 4, a GPER-selective antagonist with enhanced selectivity for GPER and decreased activity towards ERα and ERβ compared to the previously described antagonist, G15. We show that high doses of G15 induce low levels of transcription via ERα and that G36 minimizes this off-target effect. Additionally, G36 maintains equal efficacy as an antagonist of GPER compared to G15 in a range of functional assays, both in vitro and in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Molecular Docking

The crystal structure of the human estrogen receptor (ER) ligand-binding domain in complex with 17β-estradiol from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1ERE) was used [22]. The receptor was prepared for docking using the standard protocol implemented in fred_receptor, a wizard like graphical utility that prepares an active site for docking with FRED (version 2.2.5, OpenEye Scientific Software, Inc., Santa Fe, NM, USA, www.eyesopen.com, 2010). Three-dimensional conformations for the chosen ligands (E2, G-1, G15, and G36) were generated using OMEGA (version 2.3.2, OpenEye Scientific Software, Inc., Santa Fe, NM, USA, www.eyesopen.com, 2010) and the ligands were docked in the binding site of the receptor with FRED, using the default docking parameters. The Chemgauss3 scoring function, which uses Gaussian smoothed potentials to measure the complementarity of ligand poses within the active site, was used to evaluate and compare how well the different ligands fit in the ligand binding site.

2.2. Chemical synthesis and characterization of G36 (4-(6-Bromo-benzo[1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-8-isopropyl-3a,4,5,9b-tetrahydro-3H-cyclopenta[c]quinoline)

A catalytic amount of Sc(OTf)3 (0.049 g, 0.1 mmol, 10 mol%) in anhydrous acetonitrile (1 mL) was added to a mixture of 6-bromopiperonal (0.229 g, 1.00 mmol), 4-isopropylaniline (0.135 g, 1.0 mmol) and cyclopentadiene (0.33 g, 5.0 mmol) in acetonitrile (3 mL). The reaction was stirred at ambient temperature (~23°C) for 2 h with monitoring of product formation by thin layer chromatography using 20% ethyl acetate/ hexanes eluent (Rf 0.5). The product crystallized from acetonitrile, and was filtered and washed with additional acetonitrile (5 mL) to provide the pure endo isomer as colorless solid (390 mg, 94%). Mp 135–136° C; FT-IR (KBr): 3435, 2955, 1613, 1504, 1040 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.18 (s, 1H), 7.02 (s, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.99 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 5.89-5.85 (m, 1H), 5.68-5.64 (m, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 4.10 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (bs, 1H), 3.22-3.11 (m, 1H), 2.84-2.73 (m, 1H), 2.64-2.55 (m, 1H), 1.83-1.75 (m, 1H), 1.22 (d, J = 1.5, 3H), 1.20 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.4, 147.2, 143.1, 139.9, 134.7, 134.0, 130.2, 126.8, 125.9, 124.2, 116.0, 113.0, 112.8, 108.1, 101.7, 56.8, 46.2, 42.2, 33.3, 31.3, 24.3, 24.1; HPLC-MS: Electrospray positive ion (cone voltage 62 V, Capillary Voltage 3 kV). G36 (1mg/mL CH3CN, 20 µL) was injected onto a Symmetry® C18 (5 µm, 3.0 X 150 mm, Waters) column and eluted with 60–90 % acetonitrile (gradient 1.5 % min−1) in water showed a single peak at 22.42 min (Fig 4). UV-Vis λmax 294 nm (Fig. 5). ESI-MS m/z (ES+) calcd for C22H22BrNO2 (M+H)+ 412.08; found 412.11; HRMS: calcd [M+H]+ for C22H22BrNO2 412.0905, found 412.0912.

2.3. Reagents

17β-estradiol was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). G-1 and G15 were synthesized as previously described [9, 10, 23]. pERK antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Goat-anti-rabbit HRP was from GE-Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). DMEM and RPMI 1640 were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). 32% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was obtained from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA).

2.4. Cell culture and transfection

COS7 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. SKBr3 cells were maintained in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Cells were grown as a monolayer at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. For microscopy experiments, cells were seeded onto 12 mm glass coverslips and allowed to adhere for at least 12 h prior to transfection. Twenty-four hours prior to PI3K or pERK experiments, medium was replaced with serum-free, phenol red free RPMI 1640. For experiments requiring transient transfection of PH-mRFP, ERα-GFP, ERβ-GFP or GPER-GFP, Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) was used according to manufacturers instructions. PH-mRFP was transfected at ¼ the recommended amount to achieve appropriate expression levels.

2.5. ERE activation assays

ERE activity was determined using MCF-7 cells stably transfected with an ERE-GFP reporter construct [24]. Briefly, cells were deprived of estrogen for 4 days (with one intermediate medium change) in phenol red free DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped FBS. In 24 well plates, ~80,000 cells were seeded, and 24 hours later treated with the indicated compounds (dissolved in DMSO, final DMSO 0.1% for each compound added) for 24 hours in triplicate, trysinized, washed and analyzed for green fluorescence by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence intensities were determined and normalized to E2 values following subtraction of vehicle control values.

2.6. Ligand binding assays

Binding assays for ERα and ERβ were performed as previously described [7]. Briefly, COS7 cells were transiently transfected with either ERα-GFP or ERβ-GFP. Following serum starvation for 24 h, cells (~5x104) were incubated with G36 for 20 min in a final volume of 10 µL prior to addition of 10 µL 20 nM E2-Alexa633 in saponin-based permeabilization buffer. Following 10 min at RT, cells were washed once with 200 µL PBS/2%BSA, resuspended in 20 µL and 2 µL samples were analyzed on a DAKO Cyan flow cytometer using HyperCyt™ as described [25].

2.7 Intracellular calcium mobilization

SKBr3 cells (1×107 cells/mL) were incubated in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS, Gibco) containing 3 µM indo1-AM (Invitrogen) and 0.05% pluronic acid for 1 h at RT. Cells were then washed twice with HBSS, incubated at RT for 20 min, washed again with HBSS, resuspended in HBSS at a density of 108 cells/mL and kept on ice until assay, performed at a density of 2×106 cells/mL. Ca++ mobilization was determined ratiometrically using λex 340 nm and λem 400/490 nm at 37°C in a spectrofluorometer (QM-2000-2, Photon Technology International) equipped with a magnetic stirrer.

2.8. PI3K activation

The PIP3 binding domain of Akt fused to mRFP1 (PH-mRFP1) was used to localize cellular PIP3. COS7 cells (cotransfected with GPER-GFP or ER-GFP and PH-mRFP1) cells were plated on coverslips and serum starved for 24 h followed by stimulation with ligands as indicated. The cells were fixed with 2% PFA in PBS, washed, mounted in Vectashield and analyzed by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal fluorescent microscope. Cells were preincubated with 1 µM G36 as indicated for 20 min prior to stimulation and G36 was present during stimulation.

2.9. Western Blotting

Cells were starved in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 for 24 h prior to treatment for pERK Western blots. For activation of pERK, cells were treated as indicated, washed once with ice-cold PBS and lysed using NP-40 buffer. Twenty µg protein was loaded per lane. Cells were preincubated with G15 or G36 as indicated prior to stimulation and inhibitors were present during stimulation. Band quantitation was carried out using ImageJ [26].

2.10. Mouse uterine estrogenicity assay

C57Bl6 female mice (Harlan) were ovariectomized at 10 weeks of age. E2 and G36 were dissolved in absolute ethanol at 1 mg/mL and further diluted in ethanol. For treatment, 10 µL of the appropriate dilution (of single or of combined compounds) was added to 90 µL aqueous vehicle (0.9% NaCl with 0.1% albumin and 0.1% Tween-20). Ethanol alone (10 µL) was added to 90 µL aqueous vehicle as control (sham). At 12 days post-ovariectomy, mice were injected subcutaneously with compound. Eighteen hr after injection, mice were sacrificed and uteri were dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micron sections were placed on slides, and proliferation in uterine epithelia was quantitated by immunofluorescence using anti-Ki-67 antibody (LabVision) followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa488 (Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). At least 4 animals per treatment were analyzed, and the Ki-67 immunodetection was repeated three times per mouse.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. G-1/G15 ERE-mediated activity and design/synthesis of G36

In our original identification of the GPER antagonist G15 [10], we speculated that the ethanone moiety of G-1 might be critical for GPER activation through the formation of hydrogen bonds with the receptor and that loss of this bonding would result in a compound that could still bind but not activate GPER, thus acting as a competitive antagonist. In our initial characterization of G15, we detected weak binding of G15 to ERα and ERβ at high concentrations (≥10 µM) of G15; however, there were no effects of G15 on estrogen receptor-mediated signaling observed in multiple functional assays [10]. These results supported the use of G15 as a selective GPER antagonist for in vitro and in vivo investigations. In order to assess the structural basis of the observed low-affinity binding, we performed docking studies with the 3-dimensional X-ray crystal structure of the estrogen-bound ligand binding domain of ERα (PDB ID 1ERE) [22]. E2, as expected, displayed a high binding score (−99.6) for the receptor site, the docking pose being almost identical to the ligand in the X-ray structure (RMSD=0.53 Å). Docking of G-1 resulted in a significantly worse score (−52.8), mostly due to a steric clash with the Arg394 residue in the binding site (Fig. 1), which could explain the high level of GPER selectivity shown by this ligand. However, the docking score of G15 (−76.2) indicates that this ligand has a lower steric clash than G-1 within the binding site and might therefore exhibit binding to the receptor, but with a much lower affinity than E2.

Figure 1.

Docking poses of selected ligands in the ER binding site: E2 green, G-1 magenta, G15 yellow. Arg394, which displays steric clashes with G-1 is depicted in orange in the lower left corner. The Pro399-Leu402 loop was hidden in order to better present the ligands.

To test whether G15 exhibits any activity towards ERα, we utilized a highly-sensitive estrogen response element (ERE) transcriptional assay, in which estrogenic activity through either ERα (or potentially ERβ) results in activation of a stably transfected ERE-GFP reporter construct in MCF-7 cells yielding a readout of GFP expression (Fig. 2) [24]. In this assay, high doses (≥1 µM) of G15 (concentrations 105–106 greater than that required for E2) resulted in weak activation of the ERE reporter (≤ 20% of E2 response), consistent with the initial results that G15 binds weakly to ERα and ERβ at high concentrations. To establish that the expression of GFP is mediated by ERα (or potentially ERβ), we coincubated E2 and G15 with ICI182,780 (a full ER antagonist that results in ER downregulation), which yielded complete ablation of GFP induction by both E2 and G15 (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that at high concentrations, G15 is capable of mediating limited ER-dependent transcriptional activity.

Figure 2.

High concentrations of G15 mediate weak activation of ERE. MCF-7 cells stably transfected with an ERE-GFP reporter were treated for 24 hours with the indicated concentration of E2, G-1 or G15. Whereas E2 shows half maximal activation at approximately 100 pM, G-1 shows no activation up to 10 µM. G15 exhibits limited activation (~15–20%) at concentrations ranging from 1–10 µM.

With these results in mind, we revisited the structural similarity of the GPER-selective agonist G-1 and G15. Both GPER-selective compounds are based on the same cyclopenta[c]quinoline scaffold, with the difference being the presence of an ethanone moiety on G-1 which is lacking in G15 (Fig. 3A). Based on the docking study, we postulated that the presence of this side chain on G-1 resulted in additional steric conflicts and reduced binding ability of G-1 for ERα. Since we speculated that the inability of G15 to form hydrogen bonds through the ethanone group is responsible for its antagonist activity, we further hypothesized that replacing the reactive ethanone group with a hydrophobic isopropyl group might generate a GPER antagonist with increased selectivity for GPER over ERα and ERβ compared to G15. Thus, we identified the isopropyl group as a potential isosteric replacement of the ethanone group that would lack both H-bond donor and acceptor capacity. The target compound G36 was synthesized using a three-component Povarov cyclization of 4-isopropylaniline, 6-bromopiperonal and cyclopentadiene catalyzed by Sc(OTf)3 in acetonitrile (Fig. 3B). The product crystallized from acetonitrile to afford G36 in excellent yield as a racemic mixture of the analytically pure syn/endo diastereomer.

Figure 3.

(A) Structures of estrogen (17β-estradiol) 1, G-1 2, G15 3 and G36 4. (B) Synthetic route for G36.

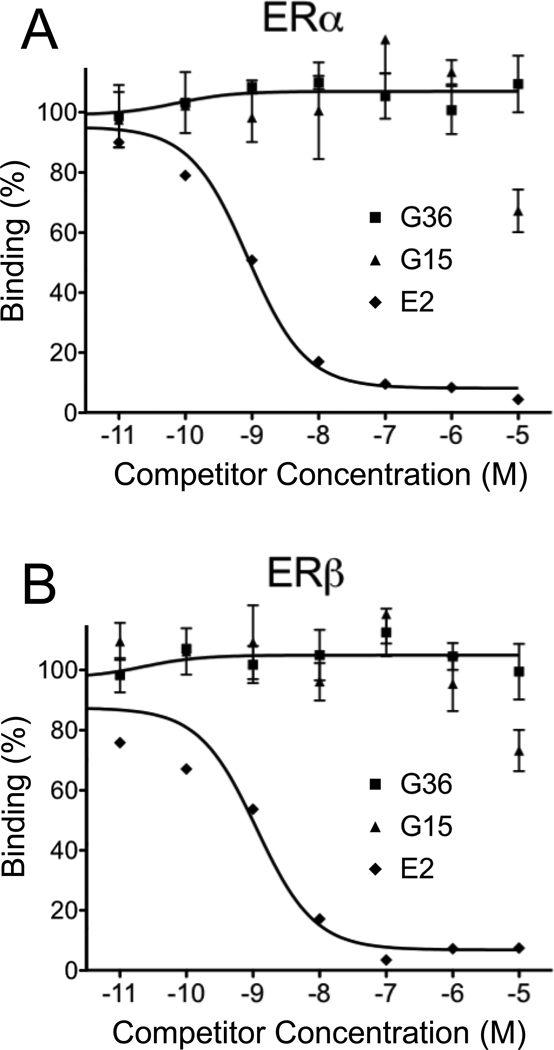

3.2. ER docking, binding and activation of G36

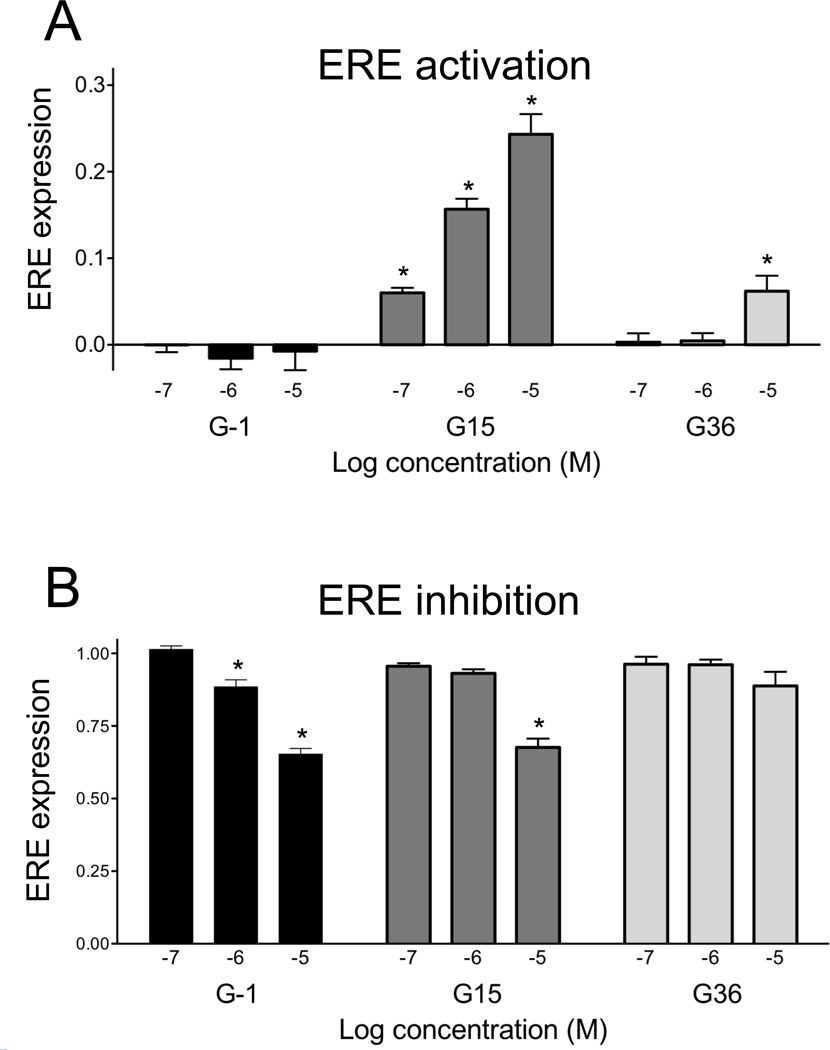

Docking analysis with G36 yielded a score (−52.3) very similar to that of G-1 with a similar steric clash of the isopropyl group with Arg 394 (Supplemental Fig. 1). To examine the binding selectivity of G36 towards ERα and ERβ, we compared the binding of G36 to that of G15 and E2 using a competitive fluorescent estrogen ligand binding assay. Results from dose-response curves confirm that G15 displays weak but significant binding to ERα and ERβ only at the highest concentration, 10 µM, with G36 lacking detectable binding activity to both ERα and ERβ over the entire range of concentrations tested (Fig. 4). It should be noted that the binding of G15 to ERα and ERβ is nevertheless weak, between 104 and 105 fold less than that of E2. These results suggested that G36 may exhibit reduced activation of ERE in comparison to G15. In addition to being a highly sensitive functional assay, one benefit of the ERE assay is that it can be used to investigate both agonist and antagonist properties of compounds. We took advantage of this property to probe more fully the activities of G-1, G15 and G36 against ERα/β (Fig. 5). We confirmed that G-1, when administered to MCF7 cells stably expressing the ERE-GFP reporter, displayed no agonist activity at doses up to 10 µM; however, when G-1 is administered at high doses it does show weak antagonism of the 1 nM E2-mediated ERE response. This finding is noteworthy, as it suggests that G-1 should optimally be used at sub-micromolar concentrations when investigating GPER function in complex systems where transcriptional effects may be relevant, thus limiting possibly confounding results from potential inhibition of estrogen-mediated transcriptional effects via ERα/β. Most published work has employed G-1 at sub-micromolar doses (typically 10–100 nM, occasionally ~1 µM), so the finding that G-1 antagonizes ERα/β function at high doses does not detract from such studies, particularly since most studies are carried out over short (i.e. non-genomic) time frames and in the absence of added estrogen.

Figure 4.

G36 exhibits improved binding selectivity towards ERα and ERβ compared to G15. Dose response profile of E2, G15 and G36 for competition of E2-Alexa633 binding to ERα-GFP (A) or ERβ-GFP (B). G36 shows decreased binding to ERα and ERβ at the highest concentration compared to G15.

Figure 5.

G36 exhibits reduced activity towards ERE activation and inhibition compared to G15. (A) Activation of ERE-GFP response in MCF7 cells by increasing concentrations of G-1, G15 and G36. (B) Inhibition of ERE response induced by 1 nM E2 as a function of increasing concentrations of G-1, G15 and G36. *, p<0.05 vs. DMSO alone (A) or 1 nM E2 (B).

In contrast to G-1, G15 demonstrates limited agonism of the ERE reporter (Fig. 5) with ~15% activity at 1 µM and ~25% activity at 10 µM compared to the maximal E2 response (10 nM, see Fig. 2). Additionally, G15 inhibits the E2-induced ERE response by ~30% when administered at 10 µM with no significant effect at 1 µM. These results suggest that G15 likely functions as a partial agonist of transcription mediated by ERs. Our prior studies however demonstrated that G15 does not mediate rapid signaling events via either the MAPK or PI3K pathways in ERα- or ERβ- expressing cells [10], suggesting that the partial agonist activity seen here applies only to transcriptional signaling through the classical ERs and not to ER-mediated rapid signaling events. This separation of rapid and genomic signaling events has previously been observed with androgen receptor ligands, with some promoting genomic signaling and others preferentially activating non-genomic pathways [27, 28]. In contrast to G15, G36 shows much lower activity in the ERE activation assay, with no significant ERE response elicited by G36 concentrations up to 1 µM and only ~5% activation at 10 µM compared to ~25% for G15 at 10 µM. G36 also shows no ability to antagonize E2-mediated ERE response at concentrations up to 10 µM. It should be noted that the inhibitory effects of G-1 and G15 on estrogen-induced transcription were absent when E2 was used at 10 nM (data not shown), suggesting that the inhibitory effects are only present at low estrogen concentration. Nevertheless, these results, along with the ERα and ERβ binding data, suggest that G36 has decreased activity via ERα and ERβ compared to the previously described GPER antagonist, G15.

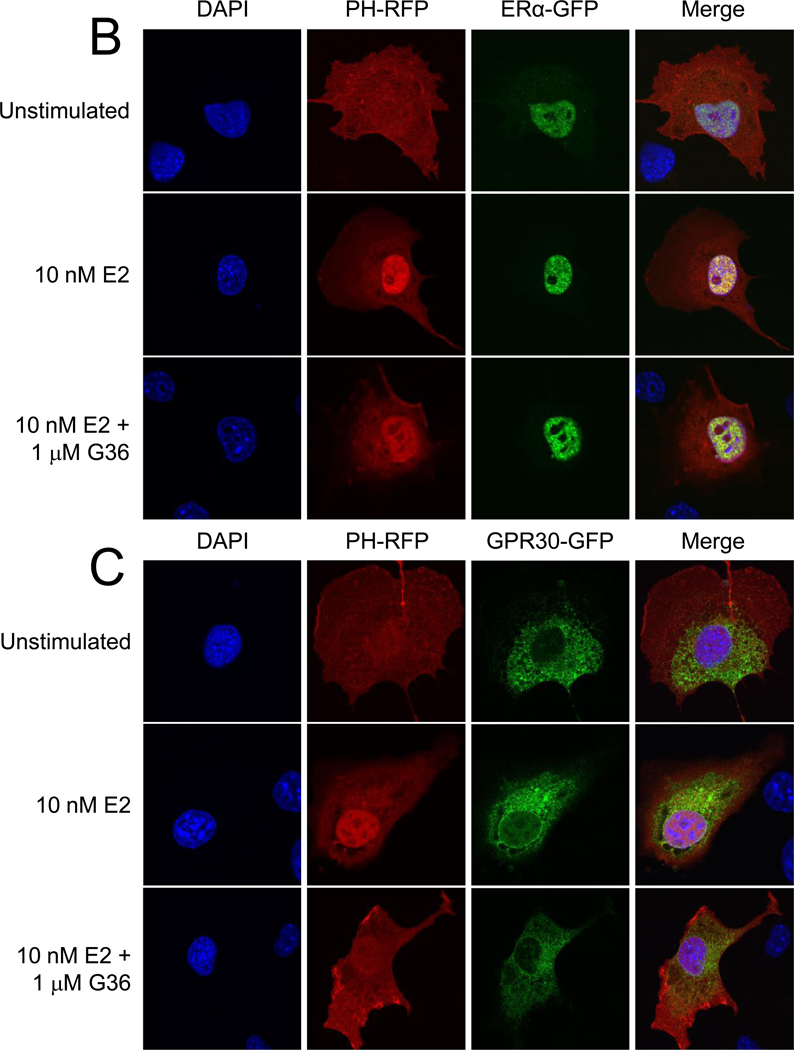

3.3. G36 selectively inhibits estrogen-mediated PI3K activity through GPER

We next investigated whether G36 maintains the inhibitory activity towards GPER displayed by G15 [10]. First, to examine PI3K activation of endogenous receptors, COS7 cells were transfected with PH-RFP, a fluorescent reporter of PIP3 localization whose nuclear translocation is used to assess PI3K activation [7]. Neither E2 nor G-1 nor G36 at a concentration of 10 uM demonstrated any activation of PI3K, indicating that COS7 cells do not exhibit either receptor-mediated or non-specific responses to any of these ligands (Fig. 6A). Next, COS7 cells were transiently transfected with either ERα-GFP or GPER-GFP and PH-RFP. As expected, due to its minimal activity in ERE assays, G36 did not inhibit E2-mediated PI3K activation in cells expressing ERα-GFP (Fig. 6B). Conversely, in cells expressing GPER-GFP, G36 effectively inhibited PI3K activation induced by E2 (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the modifications made to the initial chemical scaffold had maintained the GPER antagonist activity while decreasing the ERα activity of G15.

Figure 6.

G36 inhibits E2-induced PI3K activation in cells expressing GPR30, but not in cells expressing ERα. (A) COS7 cells (which lack endogenous ERα, ERβ and GPER) transiently transfected with only PH-RFP show no activation of PI3K, as evidenced by the lack of nuclear translocation of PH-RFP, in response to E2, G-1 or G36 (all at 10 µM). (B) COS7 cells transiently transfected with ERα-GFP and PH-RFP activate PI3K, as evidenced by nuclear translocation of PH-RFP, in response to E2 and this response is not inhibited by the presence of G36. (C) In COS7 cells transiently transfected with GPR30-GFP and PH-RFP, G36 inhibits the PI3K activation induced by E2.

3.4. G36 inhibits estrogen- and G-1-mediated calcium mobilization

In order to determine the potency of G36 compared to G15, we assayed the ability of G36 to inhibit both E2- and G-1-mediated calcium mobilization in SKBr3 cells, which endogenously express only GPER and neither ERα nor ERβ. Both E2 and G-1 mediated similar levels of calcium mobilization at 200 nM (Fig. 7A). To determine the potency of G36, cells were stimulated with a constant dose of E2 or G-1 and increasing concentrations of G36 were used to generate a dose-response curve (Fig. 7B). IC50 values for G36 inhibition of E2 and G-1 mediated calcium mobilization were similar, with G36 having an IC50 of 112 nM for E2 and 165 nM for G-1. These values compare favorably with those found for G15 in the same assay [10], with G36 showing slightly higher potency for inhibiting E2-mediated (G36 IC50 = 112 nM, G15 IC50 = 190 nM) calcium mobilization and essentially identical potency for G-1-mediated (G36 IC50 =165 nM, G15 IC50 =185 nM) calcium mobilization. To assess whether G36 might act non-specifically to inhibit calcium mobilization, we tested G36 at 10 µM for its effect on calcium mobilization by an unrelated GPCR, specifically endogenous purinergic receptors (Fig. 7C). G36 exhibited no inhibition of calcium mobilization by 1 µM ATP, indicating high selectivity for GPER. Furthermore, G36 itself did not alter the basal calcium level in cells (Fig. 7C, first arrow). Thus, G36 affords enhanced selectivity as an antagonist of GPER with similar potency in the inhibition of GPER function when compared to G15.

Figure 7.

G36 inhibits E2 and G-1 mediated calcium mobilization in SKBr3 cells. (A) SKBr3 cells, which endogenously express only GPR30 but neither ERα nor ERβ, were monitored for calcium mobilization induced by either E2 (200 nM) or G-1 (200 nM). DMSO was added at the first arrow as a control and either E2 or G-1, as indicated at the second arrow. (B) Purinergic receptor activation (by 1 µM ATP, second arrow) was not inhibited by pretreatment with 10 µM G36 (first arrow). (C) E2- and G-1-mediated calcium mobilization are inhibited by increasing concentrations of G36 (pre-incubated for ~2 min, following the scheme in A). Data is normalized to E2 (200 nM) or G-1 (200 nM) activation of calcium mobilization in the presence of vehicle control (DMSO) as shown in A.

3.5. G36 inhibits estrogen- and G-1-mediated but not EGF-mediated ERK activation

Since activation of the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway was one of the functions first attributed to GPER [6], we verified the activity of G36 as an antagonist of GPER function in ERK activation (Fig. 8). SKBr3 cells, which express only GPER and neither ERα nor ERβ, were stimulated with E2, the GPER-selective agonist G-1. With both stimuli, we detected a 5–6 fold increase in the level of pERK. Upon stimulation in the presence of either G15 or G36, we observed a significant decrease in the E2- and G-1-induced ERK activation. To test for possible non-specific effects of G36 or G15, we examined EGF-induced ERK activation, which was unchanged by the presence of either G15 or G36, illustrating the selectivity of each of these molecules for GPER.

Figure 8.

G36 inhibits ERK activation induced by E2 and G-1 via GPR30. SKBr3 cells were stimulated with E2 (10 nM), G-1 (10 nM) or EGF (10 ng/mL) in the presence of vehicle control (DMSO), 1 µM G15 or G36 (pre-incubated for 15 min) and analyzed for pERK and total ERK levels by Western blot. Quantitation of pERK activation was from three independent experiments. *, p<0.05 vs. DMSO alone.

3.6. G36 inhibits estrogen- and G-1-mediated uterine proliferation

In order to extend our findings in vivo, we evaluated the effect of G36 in the proliferative response of the uterine epithelium (Fig. 9). Upon administration of E2, uterine epithelia exhibit increased proliferation, as evidenced by the increase in the percent of cells staining positive for the proliferation marker Ki-67. As we have previously observed [10], G-1 can also induce significant proliferation of uterine epithelia, albeit to a substantially lesser extent than E2. This result is most likely due to E2 activating the full cohort of estrogen receptors in the mouse (ERα, ERβ and GPER), whereas G-1 only activates GPER, which alone cannot fully recapitulate the response of ERα and ERβ. G36 administered alone had no effect on proliferation, whereas G36 administered with G-1 completely abrogated the proliferative response to G-1, as expected of a GPER antagonist. Combination treatment with E2 and G36 resulted in a significant decrease in proliferation compared to E2 treatment, consistent with the inhibition previously observed with G15. These in vivo results confirm our in vitro findings that G36 is a GPER antagonist and demonstrate the utility of GPER-selective agonists and antagonists in a complex model system.

Figure 9.

G36 inhibits GPR30-mediated proliferation in vivo. Epithelial uterine cell proliferation was assessed in the presence of E2, G-1, G36, G-1 + G36 or E2 + G36. Amounts injected were as follows: E2: 10 ug/kg; G-1: 10 ug/kg; G36 (alone or in combination): 50 ug/kg. Ki-67 positivity of the uterine epithelium was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. *, p<0.05 vs. sham; **, p<0.05 vs. E2.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a second generation GPER antagonist G36 with improved performance and selectivity that exhibits significantly decreased off-target effects on ERα and ERβ compared to our previously described antagonist, G15. It is however important to note the context in which both G-1 and G15/G36 are likely to be used. G-1 has typically been used to determine the contribution of GPER activation to a cellular or physiological response in the absence of estrogen, either by its omission in culture medium or following ovariectomy in mice. Thus, although G-1 may exhibit slight inhibitory activity on estrogen-mediated ERE activation, its complete lack of stimulatory activity represents the more important consideration. For G-1, it is not clear that the inhibitory activity is a result of ER binding, as we were previously unable to detect significant competition even at 10 µM [9]. It is therefore possible that this inhibitory effect is indirect as a result of rapid signaling initiated by GPER. Interestingly, very high doses of G-1 have recently been shown to inhibit estrogen-mediated uterine epithelial cell proliferation in vivo through inhibition of stromal ERK1/2 activation and ERα phosphorylation [29]. Alternatively, G15 demonstrates both binding at high concentrations as well as stimulatory activity in the absence of estrogen and inhibitory activity in the presence of estrogen. The observation of binding suggests that these functional effects may be direct via ERα binding. However, G15 would typically not be used alone (except as a negative control) and thus the stimulatory activity would likely not be of concern, unless potentially used in combination with G-1, where ERE activation could confound results. Furthermore, any effects would be limited to “long-term” assays where ERE activation could be involved and not rapid or acute events (e.g. <1 hour).

The improved selectivity of G36 in terms of <~5% activation and inhibition of ERE-mediated transcription at 10 µM will make it highly useful for probing the functions of GPER in a wide range of complex assays and model systems that express one or both of the classical ERs in addition to GPER. Nevertheless, as with any pharmacological agent, conclusions regarding the involvement of the presumed target should be confirmed with the use of siRNA or knockout mice where possible. Building from the numerous documented successful applications using G15 to examine the contributions of GPER to estrogen physiology, we believe that the development of G36 will give researchers a more selective tool to investigate GPER function.

Highlights.

We identify a GPER antagonist G36 with increased selectivity against ERα/β

G36 exhibits reduced ER binding/activation compared to G15

G36 inhibits GPER activity with similar efficacy to G15

Highly selective GPER ligands provide an important tool to discover GPER biology

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Docking pose of G36 (dark blue) in the ER binding site compared to G-1 (magenta). Arg394, which displays strong steric clashes with G-1 and G36, is depicted in the lower left corner with the side chain in dark orange with nitrogen atoms in lighter blue. The Pro399-Leu402 loop was hidden in order to better see the docked ligands. Oxygen and bromine atoms on G-1 and G36 are shown in red.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA127731 (ERP, JBA, TIO), CA118743 (ERP) and CA116662 (ERP), and MH084690 (LAS); the New Mexico Cowboys for Cancer Research Foundation (JBA, ERP); Oxnard Foundation (ERP); and the Stranahan Foundation (ERP). Fluorescence microscopy images were generated in the University of New Mexico Cancer Center Fluorescence Microscopy Facility supported as at http://hsc.unm.edu/crtc/microscopy/Facility.html.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information Available: This material is available free of charge via the Internet at www…….

References

- 1.Edwards DP. Regulation of signal transduction pathways by estrogen and progesterone. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lange CA, Gioeli D, Hammes SR, Marker PC. Integration of rapid signaling events with steroid hormone receptor action in breast and prostate cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007;69:171–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.160319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Hathaway HJ. Estrogen signaling through the transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor GPR30. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albanito L, Madeo A, Lappano R, Vivacqua A, Rago V, Carpino A, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Musti AM, Ando S, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) mediates gene expression changes and growth response to 17beta-estradiol and selective GPR30 ligand G-1 in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(4):1859–1866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandey DP, Lappano R, Albanito L, Madeo A, Maggiolini M, Picard D. Estrogenic GPR30 signalling induces proliferation and migration of breast cancer cells through CTGF. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):523–532. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14(10):1649–1660. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307(5715):1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prossnitz ER, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Arterburn JB. GPR30: a novel therapeutic target in estrogen-related disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29(3):116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2(4):207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis MK, Burai R, Ramesh C, Petrie WK, Alcon SN, Nayak TK, Bologa CG, Leitao A, Brailoiu E, Deliu E, Dun NJ, Sklar LA, Hathaway HJ, Arterburn JB, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. In vivo effects of a GPR30 antagonist. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(6):421–427. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng J, Wang ZY, Prossnitz ER, Bjorling DE. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 inhibits human urothelial cell proliferation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(8):4024–4034. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhn J, Dina OA, Goswami C, Suckow V, Levine JD, Hucho T. GPR30 estrogen receptor agonists induce mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;27(7):1700–1709. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noel SD, Keen KL, Baumann DI, Filardo EJ, Terasawa E. Involvement of G-Protein Coupled Receptor 30 (GPR30) in Rapid Action of Estrogen in Primate LHRH Neurons. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:349–359. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and characterization of estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the rat central nervous system. J. Endocrinol. 2007;193(2):311–321. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Dehghani B, Li Y, Kaler LJ, Proctor T, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Membrane estrogen receptor regulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through up-regulation of programmed death 1. J. Immunol. 2009;182(5):3294–3303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blasko E, Haskell CA, Leung S, Gualtieri G, Halks-Miller M, Mahmoudi M, Dennis MK, Prossnitz ER, Karpus WJ, Horuk R. Beneficial role of the GPR30 agonist G-1 in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2009;214(1–2):67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas E, Bhattacharya I, Brailoiu E, Damjanovic M, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Mueller-Guerre L, Marjon NA, Gut A, Minotti R, Meyer MR, Amann K, Ammann E, Perez-Dominguez A, Genoni M, Clegg DJ, Dun NJ, Resta TC, Prossnitz ER, Barton M. Regulatory role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor for vascular function and obesity. Circ. Res. 2009;104(3):288–291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindsey SH, Carver KA, Prossnitz ER, Chappell MC. Vasodilation in response to the GPR30 agonist G-1 is not different from estradiol in the mRen2.Lewis female rat. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182135f1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peyton C, Thomas P. Involvement of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling in Estrogen Inhibition of Oocyte Maturation Mediated Through the G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor (GPER) in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Biol. Reprod. 2011 doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088765. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gingerich S, Kim GL, Chalmers JA, Koletar MM, Wang X, Wang Y, Belsham DD. Estrogen receptor alpha and G-protein coupled receptor 30 mediate the neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol in novel murine hippocampal cell models. Neuroscience. 2010;170(1):54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenei-Lanzl Z, Straub RH, Dienstknecht T, Huber M, Hager M, Grassel S, Kujat R, Angele MK, Nerlich M, Angele P. Estradiol inhibits chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via nonclassic signaling. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;62(4):1088–1096. doi: 10.1002/art.27328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brzozowski AM, Pike AC, Dauter Z, Hubbard RE, Bonn T, Engstrom O, Ohman L, Greene GL, Gustafsson JA, Carlquist M. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature. 1997;389(6652):753–758. doi: 10.1038/39645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burai R, Ramesh C, Shorty M, Curpan R, Bologa C, Sklar LA, Oprea T, Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB. Highly efficient synthesis and characterization of the GPR30-selective agonist G-1 and related tetrahydroquinoline analogs. Org Biolmol Chem. 2010;8:2252–2259. doi: 10.1039/c001307b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamaguchi Y, Takei H, Suemasu K, Kobayashi Y, Kurosumi M, Harada N, Hayashi S. Tumor-stromal interaction through the estrogen-signaling pathway in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4653–4662. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez S, Aiken CT, Andrzejewski B, Sklar LA, Edwards BS. High-throughput flow cytometry: validation in microvolume bioassays. Cytometry A. 2003;53(1):55–65. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasband W. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, O'Brien CA, Bodenner DL, Han L, Han K, DiGregorio GB, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104(5):719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gill A, Jamnongjit M, Hammes SR. Androgens promote maturation and signaling in mouse oocytes independent of transcription: a release of inhibition model for mammalian oocyte meiosis. Molecular Endocrinology. 2004;18(1):97–104. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao F, Ma X, Ostmann AB, Das SK. GPR30 Activation Opposes Estrogen-Dependent Uterine Growth via Inhibition of Stromal ERK1/2 and Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ER{alpha}) Phosphorylation Signals. Endocrinology. 2011 doi: 10.1210/en.2010-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Docking pose of G36 (dark blue) in the ER binding site compared to G-1 (magenta). Arg394, which displays strong steric clashes with G-1 and G36, is depicted in the lower left corner with the side chain in dark orange with nitrogen atoms in lighter blue. The Pro399-Leu402 loop was hidden in order to better see the docked ligands. Oxygen and bromine atoms on G-1 and G36 are shown in red.