Abstract

We evaluated the drug release capability of optically transparent recombinant silk-elastinlike protein polymer, SELP-47K, films to sustainably deliver the common ocular antibiotic, ciprofloxacin. The ciprofloxacin release kinetics from drug-loaded SELP-47K films treated with ethanol or methanol vapor to induce different densities of physical crosslinking was investigated. Additionally, the drug-loaded protein films were embedded in a protein polymer coating to further prolong the release of the drug. Drug-loaded SELP-47K films released ciprofloxacin for up to 132 hours with near first-order release kinetics. Polymer coating of drug-loaded films prolonged drug release for up to 220 hours. The antimicrobial activity of ciprofloxacin released from the drug delivery matrices was not impaired by the film casting process or the ethanol or methanol treatments. The mechanism of drug release was elucidated by analyzing the physical properties of the film specimens, including equilibrium swelling, soluble fraction, surface roughness and hydrophobicity. Additionally, the conformation of the SELP-47K and its physical crosslinks in the films was analyzed by FTIR and Raman spectroscopy. A three-parameter physics based model accurately described the release rates observed for the various film and coating treatments and attributed the effects to the degree of physical crosslinking of the films and to an increasing affinity of the drug with the polymer network. Together, these results indicate that optically transparent silk-elastinlike protein films may be attractive material candidates for novel ophthalmic drug delivery devices.

Keywords: Silk-elastinlike protein polymer, Ophthalmic material, Optical transparency, Sustained drug release, Antimicrobial assay

1. Introduction

Drug delivery systems for sustained release of therapeutic drugs to the precorneal regions of the eye are of considerable interest. Approximately 90% of ophthalmic medications on the market today are administered by topical eye drops [1]. The method is very inefficient and it fails to maintain a prolonged period of effective therapeutic drug concentration especially beneficial for the treatment of some ocular diseases. The availability of topically delivered drugs tends to be very low, as once applied to the surface of the eye, the drop is rapidly diluted and washed away by reflex tearing and dispersed by blinking. Overdosing of ocular drug solutions can compensate these effects, but greater doses can also lead to increased side effects, toxicity, and decreased patient compliance. The use of hydrophilic polymer hydrogels as ocular drug delivery devices was introduced as early as 1960 with the aim of improving drug retention on the ocular surface [2]. Since then, several researchers have designed hydrogel-based ocular drug delivery systems [3-9]. The drug release kinetics of these systems is characterized by a burst of drug delivered during the first few hours, followed by declining, sub-therapeutic drug levels in the subsequent hours. Very little drug is eluted by the second day of use. Prolonging the release of drugs at sustained therapeutic levels to the eye could be beneficial for many ophthalmic applications.

Polymers in drug release systems effectively regulate the release of drug molecules. In recent years, genetically engineered protein polymers have been developed and evaluated as matrices for controlled drug delivery [10-12]. In contrast to chemically synthesized polymers, genetic engineering of recombinant proteins has enabled the design of protein polymer biomaterials with uniform composition, molecular weight, and precisely controlled polypeptide sequences [13-15]. The repeating blocks of amino acids, responsible for distinct mechanical, chemical, and biological properties of many natural proteins, like collagen [16,17], silk [17,18], and elastin [19,20] have been widely used as design motifs. Recombinant protein polymers composed of these motifs often display properties similar to the natural proteins. For example, elastinlike proteins (ELPs) display elasticity and other physical properties like native elastin, and silklike proteins (SLPs) capable of forming β-sheet crystals have high tensile strength like native silks. By combining polypeptide sequences derived from silk and elastin, we have produced a series of silk-elastinlike protein polymers (SELPs) [10]. Notably, the silklike blocks of these protein co-polymers are able to crystallize into β-sheets via inter/intramolecular hydrogen bonding to act as physical crosslinks. In turn, the elastinlike blocks decrease the overall crystallinity of the polymer and thus enhance the solubility of SELPs. Consequently, SELPs form materials with useful mechanical strength, elasticity, and resiliency, and they have been evaluated as controlled drug release devices for a variety of biomedical applications [10,21-24].

To evaluate SELPs for ocular drug delivery, important physicochemical properties of the drug carrier, such as the equilibrium weight swelling ratio in the physiological environment, the nature of crosslinking, and the crosslinking density of the polymer, and their influence on the rate and extent of drug release must be characterized. Additionally, possible drug-carrier interactions, which may have a profound effect on drug transport within the carrier matrix, must also be assessed. Finally, for drug delivery in ocular applications, the optical transparency of the carrier is of considerable importance especially as the duration of drug delivery is increased.

In the present study, we explore the potential of SELPs to be fabricated as optically transparent thin films capable of drug loading and release. The SELP films were stabilized by EtOH or MeOH vapor treatments to induce the crystallization of the silklike polymer. The resultant films were characterized for optical transmittance, soluble fraction, and crosslinking density. The secondary structures of the polymer chains in the films with different treatments were assessed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy. The contact angle and surface roughness were measured to examine the surface properties of the films. We used ciprofloxacin, a representative broad-spectrum antibiotic typically found in eye drop formulations, to examine the drug release profiles of the films. We also evaluated the possible effects of film formation on the antimicrobial activity of the drug. We evaluated the effect on drug release of SELP coatings on the drug loaded films. Finally, we developed a physics-based model to elucidate the mechanism of ciprofloxacin transport from the drug delivery systems.

2. Materials and Methods

The SELP-47K protein polymer (884 amino acids; MW 69814) solution was generously provided by Protein Polymer Technologies, Inc. (San Diego, CA). The SELP-47K protein polymer has the repeating monomer unit of (E)4(S)4(EK)(E)3, in which S is the silklike sequence GAGAGS (one-letter amino acid abbreviation), E is the elastinlike sequence GVGVP, and EK is the pentapeptide sequence GKGVP. The complete amino acid sequence of SELP-47K has been previously reported [10], and its purity and molecular weight were examined by MALDI-TOF and SDS-PAGE in our recent study [25]. The SELP-47K solution was lyophilized and dissolved in deionized (DI) water at a concentration of 5% (w/w) at room temperature.

2.1. Optical characterization

SELP-47K films of 30 μm thickness were prepared by casting the protein solution on coverslips. Film thickness was controlled by the amount of protein solution used in the sample preparation and was measured by a Dektak 150 Surface Profiler (Veeco). Cast films were stabilized either by exposure to MeOH vapor for 24 h, denoted as MeOH-treated films, or to EtOH vapor for 48 h, denoted as EtOH-treated films. Vapor exposure was performed in a tightly sealed desicator. Following a protocol detailed elsewhere [26,27], three types of SELP-47K films, including non-treated, EtOH-treated, and MeOH-treated samples, were analyzed for optical transmittance. Briefly, a sample was taped to a sample holder with the sample facing the incident beam, and transmittance was measured using a Cary 5000 UV/VIS-NIR spectrometer (Varian). The transmittance of glass coverslip without any film sample was used to subtract the minimal effect of the coverslip from the transmittance measurement of SELP-47K films [28].

2.2. Soluble fraction and Equilibrium weight swelling analysis

The soluble fraction of EtOH- and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films was evaluated in 2 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.2 mg/ml NaN3 [29,30]. The non-treated films were not water stable, thus they could not be used for soluble fraction and swelling studies. Prior to the study, the mass of the films was measured. At predetermined time points, films were removed from PBS, extensively washed in DI water, and reweighed after drying in a fume hood with laminar air flow overnight at room temperature. The fraction of remaining mass was determined by dividing the mass at each time point by the initial mass value. The measurements were conducted on triplicate samples.

Swelling ratios of the EtOH- and MeOH-treated film samples were evaluated in DI water containing 0.2 mg/ml NaN3 to prevent biological contamination. The DI water was regularly changed several times over 72 h to ensure that dissolved solids were removed during the soak. The weight of the swollen samples (Ws) was measured after gently blotting each sample with a lint-free wipe to remove excess water. The weight of the swollen films (Ws) was measured every 24 h until they reached an equilibrium weight (<1% change in weight in 24 hours). Dry films were obtained by placing swollen films in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 24 h. After equilibrating to room temperature in a dessicator containing Drierite, dry film samples were weighed and placed back into the oven for 24 h and then reweighed. The equilibrium weight of dry films (Wd) was recorded when two consecutive measurements differed by less than 1%. The weight swelling ratio (q = Ws/Wd) and the equilibrium water content (H = (1 − Wd/Ws)×100%) of the SELP-47K film samples were calculated [29,31,32], where Ws is the swollen film weight and Wd is the dry film weight.

2.3. Raman and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The secondary structure of the SELP-47K in the films was also analyzed on a Thermo Nicolet Almega microRaman system (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a 532 nm solid-state laser as the excitation source. Additionally, the secondary structure was analyzed by FTIR on a Magna-IR 560 Nicolet spectrometer (Madison, WI) equipped with a CsI beam splitter, ZeSe attenuated total reflection (ATR) crystal, and DTGS-detector. For each spectrum, 400 scans were collected over the spectral range of 4000-650 cm-1 at a resolution of 4 cm-1. The spectrometer was continuously purged with CO2 free dry air to eliminate CO2 and H2O absorbance.

The amide I spectra of SELP-47K films in the spectral range of 1720-1580 cm-1 were deconvoluted with Gaussian band profiles on GRAMS/AI 8.0 (Thermo). The second derivative and Fourier self-deconvolution (FSD) were used to resolve individual characteristic peaks representing different secondary structures [33]. Specifically, the peak at 1616 cm-1 was assigned to aggregated strands, while peaks at 1624, 1635, 1675, and 1695 cm-1 were assigned to β-sheet and sheet like structure. Peaks at 1662 and 1684 cm-1 were assigned β-turns, and peaks at 1646 and 1653 cm-1 were assigned to irregular structures, including random coils and extended chains.

2.4. Solvent casting drug-protein films

Lyophilized SELP-47K was dissolved in DI water at a concentration of 5% (w/w). Ciprofloxacin (Sigma) was dissolved in the protein solution with a ciprofloxacin to SELP-47K mass ratio of 1:10. They were mixed thoroughly by Vortex and air bubbles were removed by centrifugation. 80 μl of ciprofloxacin-loaded protein solution was then poured into a custom-made polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) well with a diameter of 6 mm. The solvent was evaporated at room temperature in a fume hood with laminar air flow overnight at room temperature. The air-dried films which contained 0.33 mg ciprofloxacin were denoted as non-treated drug-loaded films. Some of the films were stabilized in either MeOH vapor for 24 h, denoted as MeOH-treated drug-loaded films, or EtOH vapor for 48 h, denoted as EtOH-treated drug-loaded films. Vapor exposure was performed in a tightly sealed desiccator.

2.5. Encapsulating the drug-loaded films in SELP-47K

The three types of drug-loaded films, including non-treated, EtOH-, and MeOH-treated films, were prepared as indicated above. 0.1 ml of 5% (w/w) SELP-47K solution in DI water was added to another PDMS mold with a diameter of 8 mm. After the solvent had completely evaporated, it formed the bottom layer of the composite. The non-, MeOH-, and EtOH-treated drug-loaded films were then manually pressed against the dried bottom layer [34]. 0.1 ml of 5% (w/w) SELP-47K solution in DI water was added over the film. After evaporation, the three-layered film composite samples were removed from the molds and stabilized in either MeOH vapor for 24 h or EtOH vapor for 48 h, in a tightly sealed desiccator. The final composite consisted of a thin drug-loaded film core, which was either originally untreated or treated with EtOH or MeOH, and an outer protein coating, the entire composite being either treated with EtOH- or MeOH. While the ethanol or methanol treatment of the composite affects the stability of the coating, it should be noted that it likely also affects the core. The thickness of drug-loaded protein films is in the range of 60-70 μm, while the thickness of coated drug-loaded films varies from 180-190 μm. The eight types of resultant drug-loaded film specimens and composite specimens are listed in Table 3 according to their core and coating treatments.

Table 3.

Final release amount and time required achieving 50% release of various devices and parameters used for model fit in Figs. 3-5

| Sample types * | Final release | Time to 50% release | Model parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ks (hr-1) | koff (hr-1) | ΔG (10-21J) | |||

| E | 84.0 ± 2.6% | 10 h | 0.080 | 0.0030 | 5.4 |

| M | 71.2 ± 3.2% | 15 h | 0.050 | 0.0033 | 2.5 |

| DE | 85.2 ± 4.3% | 22 h | 0.034 | 0.0010 | 7.4 |

| EE | 73.0 ± 1.9% | 18 h | 0.040 | 0.0010 | 4.0 |

| ME | 66.3 ± 1.7% | 20.5 h | 0.040 | 0.0015 | 2.2 |

| DM | 73.9 ± 4.4% | 31.5 h | 0.028 | 0.0018 | 3.5 |

| EM | 69.8 ± 2.0% | 48 h | 0.015 | 0.0020 | 3.0 |

| MM | 56.4 ± 4.3% | 46 h | 0.018 | 0.0010 | 0.5 |

E: EtOH-treated drug-loaded film without coating; M: MeOH-treated drug-loaded film without coating; DE: Originally non-treated drug-loaded core film with EtOH-treated SELP-47K coating; EE: Originally EtOH-treated drug-loaded core film with EtOH-treated SELP-47K coating; ME: Originally MeOH-treated drug-loaded core film with EtOH-treated SELP-47K coating; DM: Originally non-treated drug-loaded core film with MeOH-treated SELP-47K coating; EM: Originally EtOH-treated drug-loaded core film with MeOH-treated SELP-47K coating; MM: Originally MeOH-treated drug-loaded core film with MeOH-treated SELP-47K coating.

2.6. In vitro drug release studies

The ciprofloxacin-loaded films with and without protein coatings were placed in cylindrical polypropylene elution tubes with polyethylene caps that had been pre-warmed to 34°C. A 2 ml aliquot of pre-warmed (34°C) PBS was immediately dispensed to each tube and incubated at 34°C. At predetermined times, the elution tubes were removed from the incubator, agitated by inversion, and a 1 ml aliquot of the release medium was withdrawn and replaced with an equal volume of fresh PBS. The amount of ciprofloxacin contained in the PBS was measured with a UV/Vis NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) at a wavelength of 270 nm. The concentration and mass of the released ciprofloxacin was calculated using a standard curve prepared with known ciprofloxacin concentrations. The loading amount of ciprofloxacin was predetermined such that 100% release would allow readings within the linear measurement range of the spectrophotometer.

2.7. Model simulation of drug release

A simple, three-parameter, physics-based drug release model that considers reversible drug-carrier interaction and first-order kinetics was recently developed [35]. In this model, the drug concentration change due to mass convection/diffusion follows first-order kinetics:

| (1) |

where m and c are the mass and average drug concentration in the matrix. V and A are the volume and outer surface area of the drug carrier, and k1 is the rate constant. Rearranging the above equation results in the following form:

| (2) |

Here, kS = Ak1/V is considered a convection/diffusion rate constant.

In addition to convection/diffusion, drug-matrix interaction is another important mechanism affecting drug release kinetics. Simply assuming the drug-carrier interaction is reversible, the concentrations of free and bound drug molecules, cF and cB can be derived as follows by taking the convection/diffusion mechanism into consideration:

| (3) |

Here, kon and koff are rate constants of the association and dissociation processes. When association and dissociation reach equilibrium at t = 0, the initial amounts of free and bound drug is determined by the free energy difference between the two states, ΔG = -kBTln (kon/koff) = -kBTln (cB(0)/cF(0)). Here, kB is the Boltzmann’s constant and T is the absolute temperature (assumed to be 300 K).

The derived linear ordinary differential equations (2) can be readily solved analytically, giving the following expression used to describe the cumulative release (%) M̆t of ciprofloxacin from the drug-loaded specimens:

| (4) |

where , and − λ1,2 are the corresponding eigenvalues of the linear differential equations. In this model simulation, three independent parameters, ks, koff, and ΔG are used to fit the experimental drug release data.

2.8. Ciprofloxacin antimicrobial assay

The antibacterial activity of the eluted ciprofloxacin samples was tested using the ciprofloxacin sensitive strain, E. coli 136, and a ciprofloxacin resistant strain, E. coli 132. The ciprofloxacin resistant strain was used to insure that the bacterial killing was indeed due to the ciprofloxacin and not to any unknown inhibitory agent. The two E. coli strains (EC136S and EC132R) were cultured in Muller-Hinton medium. Before the experiment, the bacteria were grown to log phase and diluted to the appropriate concentrations for the assay. 0.1 ml of the eluted ciprofloxacin solutions were added to 1 ml aliquots of the diluted bacteria in 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes to yield a ciprofloxacin concentration of 3.5 μg/ml. Controls consisted of cultures with addition of freshly prepared ciprofloxacin at the same concentration and cultures without antibiotic. The tubes were incubated in an orbital shaker (BarnStead Inc) at 300 RPM and 37 °C. At predetermined times, the concentration of the bacteria was measured in a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000) by measuring the absorbance of the culture at 600 nm.

2.9. Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at an α level equal to 0.05 was used to determine the statistically significant differences between samples. All studies were performed in triplicate unless otherwise noted. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Optical transparency of protein polymer

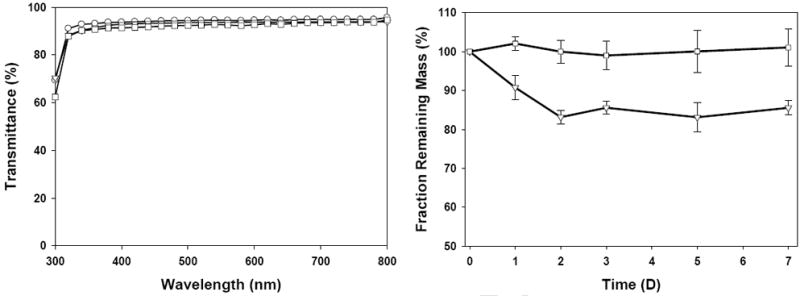

SELP-47K thin films (30 μm in thickness) are optically transparent to visible light but are opaque to ultraviolet (UV) light (Fig. 1 left). Transmittances of non-, EtOH-, and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films decrease slightly at shorter wavelengths from 95.6% at 800 nm to 93.0% at 350 nm, 93.8% at 800 nm to 90.9%, 94.6% at 800 nm to 90.4% at 350 nm, respectively. The low transmittance of SELP-47K films at wavelength below 350 nm is due to the UV absorbance of the SELP-47K amino acid side chains and the polypeptide main chain. UV absorption at 280 nm arises from aromatic amino acids [36] and absorption from 190 nm to 230 nm is due to the π −> π* transition of peptide bonds [37]. Treatment of the films with EtOH or MeOH had little effect on their transmittance.

Fig 1.

Light transmittance (left) and mass retention (right) of SELP-47K films with different treatments, including non-treated (○), EtOH-treated (▽), and MeOH-treated (□). Measurements were done in triplicate.

3.2. Protein polymer soluble fraction analysis

The soluble fraction represents the percentage of polymer chains in the initial aqueous solution that does not participate in network formation [29]. After extensive immersion in 1X PBS, EtOH-treated SELP-47K films were determined to have 15 wt% soluble fraction. The elution of the soluble fraction occurred over the first 48 hours and no further appreciable change occurred thereafter. In contrast, MeOH-treated films were determined to be stable in 1X PBS showing no detectable soluble fraction out to one week (Fig. 1 right). These results suggest that MeOH treatment induces more polymer chain entanglements and physical interactions, thus higher extent of physical crosslinking of the protein polymer chain network than does EtOH treatment. Nonetheless, EtOH treatment does substantially stabilize the structure of the SELP-47K films, in marked contrast to non-treated films that dissolve in 1X PBS (data not shown).

3.3. Equilibrium swelling study

The degree of swelling in water of SELP-47K films is an important property that may affect drug delivery. The equilibrium swelling ratio (q) and the water content (H) of MeOH- and EtOH-treated SELP-47K films were evaluated in DI water containing 0.2 mg/ml NaN3 (Table 1). Once fully hydrated, EtOH-treated SELP-47K films displayed an equilibrium swelling ratio (q) of 3.05 ± 0.14, which corresponds to 67.13 ± 1.48% (w/w) water content. For MeOH-treated films, the equilibrium swelling ratio drops to 2.03 ± 0.08, and a corresponding water content of 50.59 ± 1.97% (w/w). The decreased equilibrium swelling ratio is mainly attributed to the higher density of physical crosslinks of the MeOH-treated films. It should be noted that while the weight of the films increased substantially during swelling, their dimensions only increased slightly, e.g., less than 5% in length and width. The absorbed water likely filled the existing micro and nanopores of the films, which can be seen from SEM images of their cross-sections (Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Physical Properties of EtOH- and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films

| EtOH-treated | MeOH-treated | |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium swelling ratio (q) | 3.05 ± 0.14 | 2.03 ± 0.08 |

| Water content (H) | 67.13 ± 1.48 | 50.59 ± 1.97 |

| Contact angle | 62.61 ± 3.43° | 67.80 ± 2.15° |

| Mean surface roughness (nm) | 1.394 ± 0.217 | 1.421 ± 0.271 |

The swelling ratios of EtOH- and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films are much lower than SELP-47K hydrogels (e.g., q values in the range of 8 to 9) [29]. The major difference between SELP-47K hydrogels and films resides in the fabrication process and the resulting microstructures. When preparing films, the complete evaporation of solvent and the subsequent ethanol or methanol vapor treatment of the films enhance the interactions between the polymer chains, leading to the formation of intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds and the crystallization of the silklike blocks that greatly stabilizes the films. In contrast, the solvent retained when SELP-47K hydrogels are cured results in less crystallization of the silklike blocks. This would explain the significant differences between the swelling ratios of SELP-47K films and hydrogels.

3.4. Contact angle and Surface roughness (Ra)

The hydrophilicity of the SELP-47K film surfaces, an important parameter of films intended for use as ophthalmic materials, was evaluated by contact angle measurements (Fig. S2). The contact angles measured for EtOH- and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films were 62.61 ± 3.43° and 67.80 ± 2.15°, respectively (Table 1), comparable to those of contact lens materials such Asmoficon (71.2 ± 1.5°) and Enfilcon (68.3 ± 1.5°) [38].

The surface roughness of EtOH- and MeOH-treated SELP-47K films was analyzed using AFM. Three 2 μm × 2 μm AFM images at different locations on the film surface were acquired under the tapping mode (Fig. S3). The mean surface roughness values calculated from the three images for each type of sample were averaged (Table 1). The results indicated that the surface roughness of both types of film was comparable at the 1 nanometer scale. The typical surface roughness of polished SiO2 wafer is around 0.115 nm [39], which is about an order of magnitude less than the SELP-47K films.

3.5. Secondary structure analysis

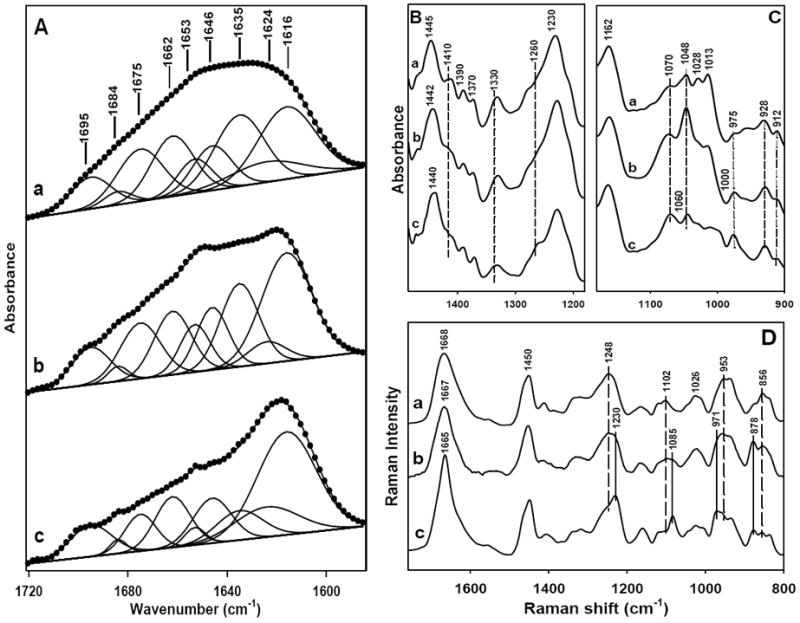

The changes in the secondary structures of SELP-47K due to physical crosslinking of the films induced by EtOH and MeOH treatment was assessed by FTIR and Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 2). In the FITR spectra, the amide I band of non-, EtOH-, and MeOH-treated films shifted from 1630 cm-1 to 1620 cm-1 and 1617 cm-1, respectively (Fig. 2A). The band shift suggested a transition from antiparallel β-sheets structure to aggregated strands[40], likely a consequence of strong intermolecular hydrogen bonding induced by the EtOH and MeOH treatments. The characteristic band of the silk I structure which comprises less-ordered conformations at 1410 cm-1 (CαH2 stretching [33]) was displayed by non-treated films but was weakened after EtOH treatment and completely disappeared after MeOH treatment. Likewise, the absorption band at 1330 cm-1 (CH3 symmetric stretching [33]) was reduced after physical crosslinking (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the band intensity at 1070 cm-1, typical of the silk II structure, which largely consists of well-defined structures, increased after EtOH treatment and became more pronounced after MeOH treatment (Fig. 2C).

Fig 2.

Spectroscopic characterization of non-treated (a), EtOH-treated (b), and MeOH-treated (c) SELP-47K films. (A) FTIR amide I spectra were fitted with Gaussian band profiles; (B) and (C) FTIR spectra; (D) Raman spectra. The spectra were intensified by about 10-fold in (C).

Raman analysis of non-treated SELP-47K films revealed Raman marker bands at 1248, 1102, 954, and 856 cm-1 (Fig. 2D), which are characteristic of the silk I structure [41,42]. After EtOH treatment, these marker bands became less distinctive. Interestingly, after MeOH treatment, SELP-47K films displayed Raman marker bands of the silk II structure at 1230, 1085, 971, and 878 cm-1 [43,44]. The silk I to silk II conversion induced by EtOH and MeOH treatments resulted in the formation of more packed, insoluble structures. Although the conversion was not complete which is indicated by the existence of weak Raman maker bands for silk I in EtOH- and MeOH-treated films, the partial conformational transition from silk I to silk II correlates with the improved stability of treated films in water, while the non-treated films were unstable once hydrated. Quantitative structural contents of SELP-47K films was obtained by deconvolution of the FTIR amide I bands with Gaussian functions (Fig. 2A, Table 2). EtOH and MeOH treatment, compared to no treatment, increased the aggregated strands from 22% to 28% and 38%, respectively, at the expense of β-sheets. Aggregated β-strands, which are more extensively hydrogen bonded, but are not necessarily more ordered than antiparallel β-sheets, likely provide SELP-47K films more robust physical crosslinks and thus greater material integrity in water.

Table 2.

Secondary structure content (%) as determined by deconvolution of the amide I bands of non-, EtOH-, and MeOH-treated films

| aggregated strands | β-sheets | β-turns | unordered structures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nontreated | 22.0 | 46.6 | 15.8 | 15.6 |

| EtOH-treated | 28.2 | 40.1 | 13.9 | 17.8 |

| MeOH-treated | 38.1 | 36.2 | 13.1 | 12.7 |

3.6. Drug release studies

3.6.1. Influence of physical crosslinking on release kinetics

The release of ciprofloxacin from eight types of drug-loaded film specimens under sink conditions at 34 °C was studied. There were statistically significant differences among the release results at an α level equal to 0.05. The release profile was characterized by two parameters used to describe release mechanisms adhering to first-order kinetics. One is the cumulative final release expressed as a percentage of the total incorporated drug. The other is the time to achieve 50% final release, which is an indicator of the drug release rate. The final cumulative release and the time required for 50% release from each type of drug-loaded specimen are summarized in Table 3.

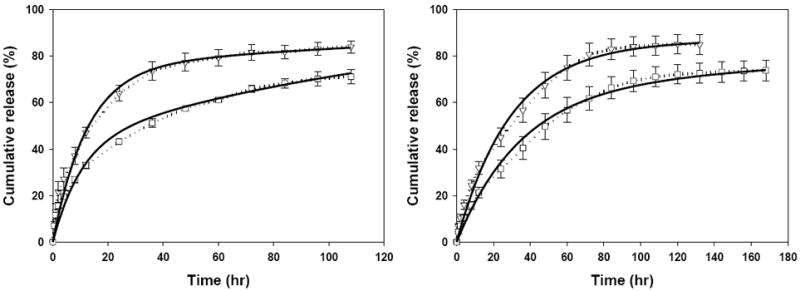

The uncoated drug-protein films E and M displayed drug release with first-order kinetics for 108 h (Fig. 3). Moreover, the device E released ciprofloxacin at a higher rate than device M. The time to 50% release for the devices E and M was 10 h and 15 h, respectively. The cumulative ciprofloxacin release reached 84.0 ± 2.6% and 71.2 ± 3.2% after 108 h for the devices E and M, with less than 1% additional release per day thereafter. The reduced release rate of ciprofloxacin from MeOH-treated drug-loaded films is likely due to their increased physical crosslinking density and enhanced stability when compared to the EtOH-treated films. As the density of physical crosslinking increases, the micro/nano-pores or channels formed inside the films become lesser and smaller which would retard the drug’s mobility through the network.

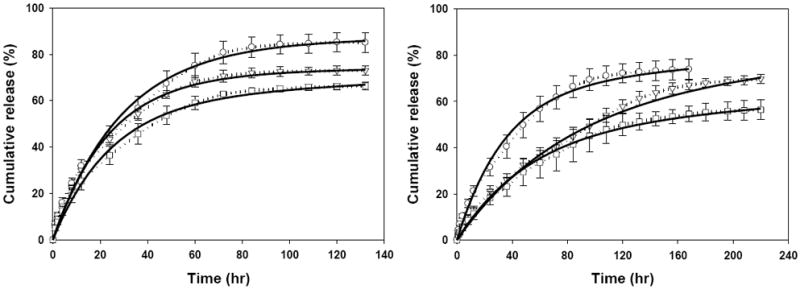

Fig 3.

Cumulative ciprofloxacin release from uncoated EtOH-treated (E, ▽), and MeOH-treated (M, □) drug-loaded films (left), and from non-treated drug-loaded film core with EtOH-treated (DE, ▽), and MeOH-treated (DM, □) SELP-47K coatings. Solid lines represent the model fit results.

3.6.2. Influence of coatings on release kinetics

With the aim towards the sustained release, we further fabricated the protein coated drug release devices which consisted of a thin drug-protein film core with a protein layer on two sides. There are six different types of coated drug release devices, including originally non-treated, EtOH-, and MeOH-treated drug-loaded film cores with the additional SELP-47K coating, the entire composite being EtOH- or MeOH-treated and abbreviated as DE, EE, ME, DM, EM, and MM. The ciprofloxacin release of these drug-loaded composite specimens was compared to investigate the influence of the different coatings and cores on the drug release parameters.

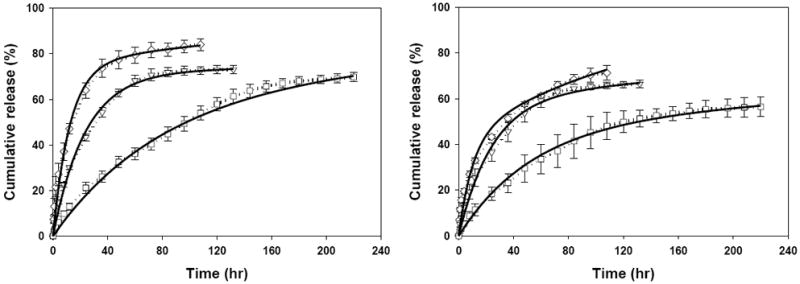

Both coated DE and DM devices displayed first-order ciprofloxacin release patterns, which continued for about 132 h (Fig. 3 right), at which time 85.2 ± 4.3% and 73.9 ± 4.4 %, respectively, of total encapsulated drug was eluted. In addition, although DE and DM specimens were composed of the same core film, the time to 50% release of the DM device was about 10 h greater than DE. The effect of different coatings was further illustrated in Fig. 4 where ciprofloxacin release from E, EE, EM (Fig. 4, left) and M, ME, MM (Fig. 4, right) was compared. We hypothesize that the coating reduces the rate of ciprofloxacin release due to its barrier effect. It follows that because MeOH-treatment induces greater physical crosslinking density compared to EtOH-treatment, MeOH-treated coatings should be more effective barriers. The barrier effect of the coatings should be evident by prolonging 50% release times. Indeed, the time required for 50% release of ciprofloxacin for devices E, EE, and EM were 10 h, 18 h, and 48 h, respectively. Likewise, the 50% release times of devices M, ME, and MM were 15 h, 20.5 h, and 46 h, respectively.

Fig 4.

Cumulative release of ciprofloxacin from EtOH-treated (left) and MeOH-treated drug-loaded film core (right) with no coating (◇), EtOH-treated (▽), and MeOH-treated (□) SELP-47K coatings. Solid lines represent the model fit results.

The barrier effect should make no appreciable difference to the final cumulative release, if there is no interaction between ciprofloxacin molecules and the SELP-47K polymer chains. Interestingly, devices E, EE, and EM had final cumulative release amounts of 84.0 ± 2.6%, 73.0 ± 1.9%, and 69.8 ± 2.0%, respectively. The final cumulative release amounts for M, ME, and MM devices were 71.2 ± 3.2%, 66.3 ± 1.7%, and 56.4 ± 4.3%, respectively. These results indicate that the ciprofloxacin could interact with the SELP-47K protein polymer chains affecting their transport from the network.

3.6.3. Influence of core properties on release kinetics

The ciprofloxacin release from DE, EE, and ME (Fig. 5, left) and DM, EM, and MM (Fig. 5, right) was compared to elucidate the influence of core physical stability on the release kinetics. The cumulative ciprofloxacin release for DE, EE, and ME specimens occurring at 130 h was 85.2 ± 4.3%, 73.0 ± 1.9%, and 66.3 ± 1.7%, respectively. Similarly, the cumulative drug release for DM, EM, and MM at up to 220 h was 73.9 ± 4.4%, 69.8 ± 2.0%, and 56.4 ± 4.3%, respectively. Therefore, the final cumulative release inversely correlated with the increased stability of the film core and the film coatings as judged by the physical analyses. However, the time to achieve 50% release did not show a consistent correlation. The 50% release times for DE, EE, and ME were 22 h, 18 h, and 20.5 h, respectively, and the values for DM, EM, and MM were 31.5 h, 48 h, and 46 h, respectively.

Fig 5.

Ciprofloxacin release kinetics from non-treated (○), EtOH-treated (▽), and MeOH-treated (□) drug-loaded film cores with EtOH-treated SELP-47K coating (left), and non-treated (○), EtOH-treated (▽), and MeOH-treated (□) drug-loaded film cores with MeOH-treated SELP-47K coating (right). Solid lines represent the model fit results.

3.7. Model simulation of drug release

The drug release observations suggest that SELP-47K film configurations affect the mechanism of ciprofloxacin release and, especially in the case of the EM and MM devices, can cause deviation from first order kinetics. A physics-based model was constructed to gain new insights into the influence of physical crosslinking, protein coatings and core composition on the release of ciprofloxacin. The comparison of model fit (solid lines) with the experimental ciprofloxacin release measurements (dashed lines) is presented in Fig. 3 to Fig. 5. The parameters used in the simulations are listed in Table 3. Notably, the model fits well the ciprofloxacin release observed from all the specimen configurations studied. In particular, both kS and ΔG values fitted for M are less than those of E, suggesting MeOH-treatment not only induces less permeability of the SELP-47K protein polymer chain network which accounts for the lower convection rate constant kS but also increases the probability of ciprofloxacin to interact with the chain network. The result agrees well with the results of the soluble fraction study and swelling test demonstrating that MeOH treatment generates higher physical crosslinking density than does EtOH treatment.

For groups DE and DM, the model simulation indicates that both kS and ΔG decrease while koff increases when comparing EtOH-treated SELP-47K coatings to MeOH-treated counterparts. For E, EE, and EM, kS and ΔG derived from the simulation decrease when the drug-loaded films are embedded in the EtOH-treated and MeOH-treated coatings. The same trend for kS and ΔG is observed for M, ME, and MM. Clearly, both types of coatings retard convection of ciprofloxacin from the drug release system to the extra-system buffer solution when compared to the non-coated devices. Furthermore, MeOH-treated coatings decrease the drug convection rate more than EtOH-treated coatings. In addition to affecting ks, the coatings, especially with MeOH treatment, increase or enhance the interaction between ciprofloxacin drug molecules and the polymer chains.

For group DE, EE, and ME, the free energy difference ΔG simulated from the physics-model decreases while the convection rate constant ks remains at a comparable level. Model fit of DM, EM, and MM revealed the same tendency for ΔG and ks. This suggests that ciprofloxacin convection/diffusion is largely affected by the type of treatment of the entire composite rather than by the original treatment of the core. This is consistent with the likelihood that EtOH- or MeOH-treatment of the composite would undoubtedly affect the structure of the core whether it was originally untreated or EtOH-treated. Compared to the non-coated EtOH- and MeOH-treated films, the decrease in ΔG in the EE and MM devices indicates that there is a combined effect of the drug-loaded core and the protein coatings, which both can intensify the interaction between ciprofloxacin molecules and the SELP-47K protein polymer chain network.

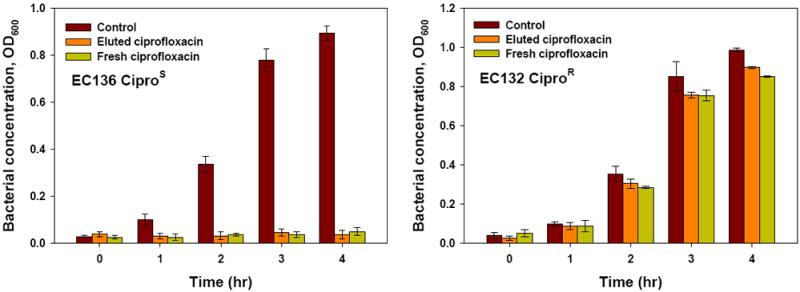

3.8. Ciprofloxacin antimicrobial assay

The antimicrobial activity of ciprofloxacin eluted from the drug-loaded film specimens was tested to ensure that the drug was not impaired by the processing steps involved in film casting or physical crosslinking, or by the extended time in buffer solution at 34 °C. The released ciprofloxacin solution was collected after 24 h of release and tested with EC136 CiproR and EC 132 CiproS bacterial strains grown in Muller-Hinton medium. Complete inhibition of ciprofloxacin sensitive E. coli 136 growth was observed, comparable to that of fresh ciprofloxacin (Fig. 6, left). For comparison, the ciprofloxacin resistant E. coli 132 exposed to ciprofloxacin continuously grew (Fig. 6, right). For both E. coli strains, their growth without any ciprofloxacin was used as control.

Fig 6.

Ciprofloxacin-sensitive E. coli strain EC 136 CiproS (left) and Ciprofloxacin-resistance E. coli strain EC 132 CiproR growth (right) with ciprofloxacin freshly prepared or released from the drug release specimen.

4. Conclusion

We have explored the potential of optically transparent protein polymer SELP-47K films in various configurations for the sustained release of a common ocular antibiotic, ciprofloxacin. The drug release kinetics can be modulated by the treatment of the films with EtOH and MeOH, which alters their physical crosslinking density and, possibly, their drug/polymer chain interactions, as measured experimentally and simulated using a physics-based mathematical model. SELP-47K film specimens released ciprofloxacin over a period of up to 220 hours, with near-first order kinetics. The rate of release was affected by the degree of physical crosslinking of the films and the presence and treatment of the SELP-47K coating. Treating the specimens with ethanol or methanol vapor controlled the degree of crosslinking of the film while not altering the chemical structure of the polymer or the drug. The incorporation of ciprofloxacin in and its release from the protein polymer films did not affect its antimicrobial activity. Thus, the optically transparent recombinant protein polymer SELP-47K could well serve as an ophthalmic material to sustainably deliver drugs of considerable therapeutic interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIBIB (R21EB009801) and NSF (CMMI0856215).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Le Bourlais C, Acar L, Zia H, Sado PA, Needham T, Leverge R. Ophthalmic drug delivery systems - Recent advances. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17:33–58. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(97)00002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wichterle O, Lim D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature. 1960;185:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlgard CC, Jones LW, Moresoli C. Ciprofloxacin interaction with silicon-based and conventional hydrogel contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens. 2003;29:83–89. doi: 10.1097/01.ICL.0000061756.66151.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulsen D, Chauhan A. Dispersion of microemulsion drops in HEMA hydrogel: a potential ophthalmic drug delivery vehicle. Int J Pharm. 2005;292:95–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiratani H, Fujiwara A, Tamiya Y, Mizutani Y, Alvarez-Lorenzo C. Ocular release of timolol from molecularly imprinted soft contact lenses. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1293–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali M, Horikawa S, Venkatesh S, Saha J, Hong JW, Byrne ME. Zero-order therapeutic release from imprinted hydrogel contact lenses within in vitro physiological ocular tear flow. J Control Release. 2007;124:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danion A, Brochu H, Martin Y, Vermette P. Fabrication and characterization of contact lenses bearing surface-immobilized layers of intact liposomes. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82A:41–51. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkatesh S, Sizemore SP, Byrne ME. Biomimetic hydrogels for enhanced loading and extended release of ocular therapeutics. Biomaterials. 2007;28:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.dos Santos JFR, Couceiro R, Concheiro A, Torres-Labandeira JJ, Alvarez-Lorenzo C. Poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-methacrylated-beta-cyclodextrin) hydrogels: Synthesis, cytocompatibility, mechanical properties and drug loading/release properties. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappello J, Crissman JW, Crissman M, Ferrari FA, Textor G, Wallis O, Whitledge JR, Zhou X, Burman D, Aukerman L, Stedronsky ER. In-situ self-assembling protein polymer gel systems for administration, delivery, and release of drugs. J Control Release. 1998;53:105–117. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(97)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagarsekar A, Ghandehari H. Genetically engineered polymers for drug delivery. J Drug Target. 1999;7:11–32. doi: 10.3109/10611869909085489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Megeed Z, Cappello J, Ghandehari H. Genetically engineered silk-elastinlike protein polymers for controlled drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2002;54:1075–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Designing materials for biology and medicine. Nature. 2004;428:487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Hest JC, Tirrell DA. Protein-based materials, toward a new level of structural control. Chem Commun (Camb) 2001:1897–1904. doi: 10.1039/b105185g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maskarinec SA, Tirrell DA. Protein engineering approaches to biomaterials design. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:422–426. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsen D, Yang CL, Bodo M, Chang R, Leigh S, Baez J, Carmichael D, Perala M, Hamalainen ER, Jarvinen M, Polarek J. Recombinant collagen and gelatin for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2003;55:1547–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foo CWP, Kaplan DL. Genetic engineering of fibrous proteins: spider dragline silk and collagen. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2002;54:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Numata K, Hamasaki J, Subramanian B, Kaplan DL. Gene delivery mediated by recombinant silk proteins containing cationic and cell binding motifs. J Control Release. 2010;146:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chilkoti A, Dreher MR, Meyer DE. Design of thermally responsive, recombinant polypeptide carriers for targeted drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1093–1111. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: Examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:357–367. doi: 10.1021/bm015630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megeed Z, Haider M, Li D, O’Malley BW, Jr, Cappello J, Ghandehari H. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of recombinant silk-elastinlike hydrogels for cancer gene therapy. J Control Release. 2004;94:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinerman AA, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Hoag SW. Solute diffusion in genetically engineered silk-elastinlike protein polymer hydrogels. J Control Release. 2002;82:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gustafson J, Greish K, Frandsen J, Cappello J, Ghandehari H. Silk-elastinlike recombinant polymers for gene therapy of head and neck cancer: From molecular definition to controlled gene expression. J Control Release. 2009;140:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Megeed Z, Cappello J, Ghandehari H. Controlled release of plasmid DNA from a genetically engineered silk-elastinlike hydrogel. Pharm Res. 2002;19:954–959. doi: 10.1023/a:1016406120288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teng WB, Cappello J, Wu XY. Recombinant Silk-Elastinlike Protein Polymer Displays Elasticity Comparable to Elastin. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:3028–3036. doi: 10.1021/bm900651g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drummy LF, Koerner H, Phillips DM, McAuliffe JC, Kumar M, Farmer BL, Vaia RA, Naik RR. Repeat sequence proteins as matrices for nanocomposites. Materials Science & Engineering C-Biomimetic and Supramolecular Systems. 2009;29:1266–1272. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kharlampieva E, Kozlovskaya V, Gunawidjaja R, Shevchenko VV, Vaia R, Naik RR, Kaplan DL, Tsukruk VV. Flexible Silk-Inorganic Nanocomposites: From Transparent to Highly Reflective. Advanced Functional Materials. 2010;20:840–846. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teng W, Huang Y, Cappello J, Wu X. Optically transparent recombinant silk-elastinlike protein polymer films. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:1608–1615. doi: 10.1021/jp109764f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dinerman AA, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Hoag SW. Swelling behavior of a genetically engineered silk-elastinlike protein polymer hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4203–4210. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pritchard EM, Valentin T, Boison D, Kaplan DL. Incorporation of proteinase inhibitors into silk-based delivery devices for enhanced control of degradation and drug release. Biomaterials. 2011;32:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Macosko CW, Urry DW. Swelling behavior of gamma-irradiation cross-linked elastomeric polypentapeptide-based hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2001;34:4114–4123. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domb A, Davidson GWR, Sanders LM. Diffusion of Peptides through Hydrogel Membranes. J Control Release. 1990;14:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taddei P, Monti P. Vibrational infrared conformational studies of model peptides representing the semicrystalline domains of Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Biopolymers. 2005;78:249–258. doi: 10.1002/bip.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ciolino JB, Hoare TR, Iwata NG, Behlau I, Dohlman CH, Langer R, Kohane DS. A drug-eluting contact lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3346–3352. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng LK, Wu XY. Modeling the sustained release of lipophilic drugs from liposomes. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitaker JR, Granum PE. An Absolute Method for Protein Determination Based on Difference in Absorbance at 235 and 280 Nm. Anal Biochem. 1980;109:156–159. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scopes RK. Measurement of Protein by Spectrophotometry at 205-Nm. Anal Biochem. 1974;59:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Read ML, Morgan PB, Maldonado-Codina C. Measurement errors related to contact angle analysis of hydrogel and silicone hydrogel contact lenses. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;91:662–668. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teichert C, Mackay JF, Savage DE, Lagally MG, Brohl M, Wagner P. Comparison of Surface-Roughness of Polished Silicon-Wafers Measured by Light-Scattering Topography, Soft-X-Ray Scattering, and Atomic-Force Microscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 1995;66:2346–2348. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson M, Mantsch HH. The Use and Misuse of Ftir Spectroscopy in the Determination of Protein-Structure. Crit Rev Biochem Mol. 1995;30:95–120. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asakura T, Ashida J, Yamane T, Kameda T, Nakazawa Y, Ohgo K, Komatsu K. A repeated beta-turn structure in poly(Ala-Gly) as a model for silk I of Bombyx mori silk fibroin studied with two-dimensional spin-diffusion NMR under off magic angle spinning and rotational echo double resonance. J Mol Biol. 2001;306:291–305. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asakura T, Yao JM, Yamane T, Umemura K, Ultrich AS. Heterogeneous structure of silk fibers from Bombyx mori resolved by C-13 solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:8794–8795. doi: 10.1021/ja020244e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng SD, Li GX, Yao WH, Yu TY. Raman-Spectroscopic Investigation of the Denaturation Process of Silk Fibroin. Appl Spectrosc. 1989;43:1269–1272. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monti P, Taddei P, Freddi G, Asakura T, Tsukada M. Raman spectroscopic characterization of Bombyx mori silk fibroin: Raman spectrum of Silk I. J Raman Spectrosc. 2001;32:103–107. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.