Abstract

Purpose

The well-known excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) assessment, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), is not consistently qualified for patients with diverse living habits. This study is aimed to build a modified ESS (mESS) and then to verify its feasibility in the assessment of EDS for patients with suspected sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in central China.

Methods

A Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire (10-ISQ) was built by adding two backup items to the original ESS. Then the 10-ISQ was administered to 122 patients in central China with suspected SDB [among them, 119 cases met the minimal diagnostic criteria for obstructive sleep apnea by sleep study, e.g., apnea and hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 h−1] and 117 healthy central Chinese volunteers without SDB. Multivariate exploratory techniques were used for item validation. The unreliable item in the original ESS was replaced by the eligible backup item, thus a modified ESS (mESS) was built, and then verified.

Results

Item 8 proved to be the only unreliable item in central Chinese patients, with the least factor loading on the main factor and the lowest item-total correlation both in the 10-ISQ and in the original ESS, deletion of it would increase the Cronbach’s alpha (from 0.86 to 0.87 in the 10-ISQ; from 0.83 to 0.85 in the original ESS). The mESS was subsequently built by replacing item 8 in the original ESS with item 10 in the 10-ISQ. Verification with patients’ responses revealed that the mESS was a single-factor questionnaire with good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86). The sum score of the mESS not only correlated with AHI (P < 0.01) but was also able to discriminate the severity of obstructive apnea (P < 0.01). Nasal CPAP treatment for severe OSA reduced the score significantly (P < 0.001). The performance of the mESS was poor in evaluating normal subjects.

Conclusion

The mESS improves the validity of ESS for our patients. Therefore, it is justified to use it instead of the original one in assessment of EDS for patients with SDB in central China.

Keywords: Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Excessive daytime sleepiness, Sleep-disordered breathing

A well-known self-perceptive assessment of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) (Appendix, items 1–8) [1]. The ESS has been translated into several languages and validated in populations of different lifestyles and economic backgrounds [2–11]. Two Chinese language versions have been previously validated using test groups from Hong Kong [12] and Taiwan [13]. However, the lifestyles and economic backgrounds of the populations in these two regions differ from those in mainland China.

Given the behavioral differences between regions and ethnic groups, as well as evidence of the inaccuracy of the ESS from previous studies [14–16], we believe that modification of the questionnaire is necessary before it can be applied as a routine clinical tool for EDS assessment in mainland China.

Materials and methods

The eight situations described in the original English language ESS were translated into official Chinese language (Mandarin) as suggested by previous guidelines [17, 18]. The first author of this article, a native Chinese speaker, made the initial English–Chinese translation. The Chinese version was then verified via backward translation into English by two bilingual physicians. Each item was discussed until agreement was reached on an appropriate translation, always striving to keep the sentences conceptually understandable and simple (Appendix, item 1–8). The final Chinese translation of the questionnaire is nearly the same as the translation made by a group of physicians in Taiwan [13], where Mandarin Chinese is also the official language. Consent for the use of ESS for validation in China was obtained from its creator, Dr. Murray Johns.

Two newly designed backup items, in accordance with the living habits of the people in central China (Appendix, items 9 and 10), were added to the original ESS. The Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire (10-ISQ) and the original ESS were used as the basis for identifying eligible items.

Selection of the two back up items was based on the following reasons:

Games such as mahjong, poker, and chess are very popular in the region studied;

The majority of people in this region habitually takes a nap after lunch;

It has been long noticed in our clinical practice that the patients with SDB were likely to doze off in these two situations.

If an item in the original ESS was proved unreliable by multivariate exploratory statistics as detailed below, it would be replaced by an eligible backup item, thus a modified ESS (mESS) with the same scale as the original one would be built.

All subjects, whether patients or normal subjects, came from Hubei and Henan, two provinces in central China that share a common border. The patients recruited in this study were consecutive patients referred to our sleep laboratory for sleep evaluation because of suspected sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Their ages ranged between 18 and 65 years. Chief complaints of most of our patients were feeling sleepy during the daytime, loud snoring at night or longstanding abnormal pauses in breathing during sleep. None of the subjects reported chronic use of medicines with hypnotic effects, such as antihistamines, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates. The normal subjects recruited were healthy, aged between 18 and 65 years. They did not snore, did not do regular shift work, or have any other medical conditions requiring chronic treatment.

Prior to the nocturnal sleep study, the patient was asked to rate on a scale of 0 ~ 3 how likely he/she would be to doze off in the situations described in the 10-ISQ based on his/her usual way of life in recent months (1 to 3 months or so). If the subject had not experienced some situations, he/she was recommended to imagine how each might affect him/her. Patients were also asked to note their experience with driving. Refusal to cooperate was rare and only happened in two or three cases with very late arrival; inadequate time was their main excuse for not participating.

Multivariate exploratory techniques, including reliability/item analysis and factor analysis, were used for item validation, and then the mESS was built. Patients diagnosed with severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) [apnea and hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 30 h−1] who tolerated long-term treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) were administrated the mESS again 3 months later in order to assess interpretability of score changes.

Results

The performances of the 10-ISQ and the original ESS were good for patients but not for normal subjects (Table 1). However, item 8 in the patients’ response showed a very low item-to-total correlation. Deletion of it would increase the standardized values of Cronbach’s alpha, from 0.86 to 0.87 for the 10-ISQ and from 0.83 to 0.85 for the original ESS. The items had more factor loading on the principal factor, which was supposed to be the assessment of EDS, were items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 but not 8 (Table 2). Only 31 out of 122 (25.4%) patients reported that they drive often.

Table 1.

Reliability/item analysis for the Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire, the original Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and the modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale (mESS)*

| Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire | ESS | mESS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal subjects (n = 117) | Patients (n = 122) | Normal subjects (n = 117) | Patients (n = 122) | Normal subjects (n = 117) | Patients (n = 122) | |||||||

| Item number | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted | Item-total correlation | Alpha if deleted |

| Item1 | 0.28 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 0.80 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.70 | 0.84 |

| Item2 | 0.23 | 0.47 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| Item3 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.83 |

| Item4 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.86 |

| Item5 | 0.23 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.85 |

| Item6 | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.85 |

| Item7 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.81 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.85 |

| Item8 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 0.22 | 0.85 | ||||

| Item9 | 0.31 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.85 | ||||||||

| Item10 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.85 | ||||

| Total | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.40 | 0.83 | 0.42 | 0.86 | ||||||

* Original Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is the composition of items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8; modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale (mESS) is the composition of items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 10; Alpha in this table indicates standardized Cronbach’s alpha

Table 2.

Factor loadings (Varimax normalized) and eigen values for Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaires and modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale (mESS)*

| Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaires | mESS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal subjects (n = 117) | Patients (n = 122) | Normal subjects (n = 117) | Patients (n = 122) | ||||

| Item number | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 1 |

| Item1 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 0.79 |

| Item2 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.76 |

| Item3 | 0.67 | 0.25 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.14 | 0.81 |

| Item4 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.64 |

| Item5 | 0.16 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.05 | 0.56 | 0.68 |

| Item6 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.69 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.65 |

| Item7 | 0.17 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| Item8 | 0.01 | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.79 | |||

| Item9 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 0.23 | |||

| Item10 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.69 |

| Eigen valuea | 1.89 | 1.48 | 4.57 | 1.20 | 1.66 | 1.40 | 4.11 |

* mESS is the composition of items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 10 from Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire

aOnly eigen values > 1 are shown

The mESS was thus built by substitution of item 8 in the original ESS with item 10 in the 10-ISQ. Improvement was demonstrated in patients’ response (but not in normal subjects’ response) that the mESS had better internal consistency than the original ESS (Cronbach’s alpha increased from 0.83 to 0.86) and assessed only one main factor (Table 1 and 2).

Among the 122 patients with suspected SDB, 119 met the minimal diagnostic criteria for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) by sleep study, e.g., apnea and hypopnea index (AHI) ≥ 5 h−1. The patients with more severe OSA had higher mESS scores (P < 0.01 by ANOVA and post hoc Scheffés test, Table 3). Among those parameters relevant to SDB, such as age, body mass index (BMI), AHI, and percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation below 90% (SpO2 < 90), AHI was the best predictor of the mESS score, as demonstrated by multiple regression test (P < 0.01, Table 4).

Table 3.

Demographic data and mESS scores in patients and in normal subjects

| OSA (n = 119) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 122) | Mild (5 ≤ AHI < 15 h−1, n = 25) | Moderate (15 ≤ AHI < 30 h−1, n = 20) | Severe (AHI ≥ 30 h−1, n = 74) | Normal subjects n = 117 | |

| Age, years | 46.7 ± 11.9a | 44.3 ± 9.7 | 45.2 ± 14.3 | 47.8 ± 11.9 | 44.2 ± 9.3 |

| Gender, female/male | 17/105 | 5/20 | 4/16 | 7/66 | 27/117 |

| BMI | 26.1 ± 3.7b | 24.6 ± 3.4 | 25.4 ± 2.7 | 27.0 ± 3.5 | 20.9 ± 2.4 |

| AHI | 36.0 ± 20.1 | 10.9 ± 3.0 | 20.8 ± 3.4 | 50.0 ± 11.8 | |

| SpO2 < 90, % | 16.2 ± 19.3 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 6.4 | 25.5 ± 19.7 | |

| mESSc | 11.0 ± 5.0b | 5.7 ± 2.6 | 8.8 ± 3.5 | 13.8 ± 3.8 | 5.7 ± 2.2 |

Data expressed as mean ± SD

OSA = Obstructive sleep apnea, confirmed by sleep study; AHI = apnea and hypopnea index; SpO2 < 90 = percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation below 90%

a P > 0.05, vs. normal subjects, by ANOVA

b P < 0.01, vs. normal subjects, by ANOVA

cDifferences in the mESS scores in patients with mild, moderate, and severe OSA are statistically significant; P < 0.01, by ANOVA and post hoc Scheffé test

Table 4.

Correlation of mESS score to parameters of sleep study for patients with OSA, evaluated by multiple regression test*

| Beta | P values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.07 | 0.27 |

| BMI | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| AHI | 0.59 | <0.01 |

| SpO2 < 90 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

*Adjusted R2 = 0.50, n = 119, P < 0.01

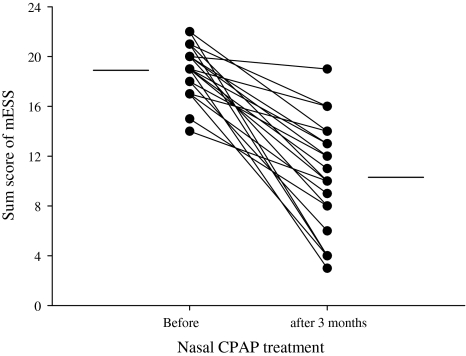

The mESS scores for the 21 patients (aged 41.8 ± 11.9 years; 19 men, 2 women) with severe OSA and good compliance to nCPAP were 18.9 ± 2.1 before treatment and 10.3 ± 4.4 after 3 months of treatment, as shown in the Fig. 1 (t test, t = 8.50, P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

For 21 patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea, the sum scores of the modified ESS before and after nasal CPAP treatment for 3 months are shown (P < 0.001). The two values for individual patients are connected with straight lines; mean values before and after the treatment period are represented by horizontal lines

Discussion

Previous validations of the Chinese versions of the ESS using multivariate exploratory techniques in Hong Kong [12] and Taiwan [13] had consistently shown that the internal homogeneity was satisfactory when the questionnaire was applied to OSA patients (Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 and 0.81, respectively). Unlike our results, the Taiwanese study [13] (the Hong Kong study did not provide information about item reliability) showed that item 8 was reliable, and the ESS measured one main factor. Therefore, the application of ESS to Taiwanese patients without any modification seems to be reasonable.

Lack of driving experience might be one of the reasons for our patients’ poor responses to item 8; nearly 75% of them did not drive or was rare to drive. Our current study is not the only one indicating that item 8 is unreliable. A recent study for ESS using confirmatory factor analysis based on OSA patients in Australia also demonstrated that the original ESS was not an accurate measurement [16]. Of particular note in this study was that item 8 had the lowest standardized regression weights, and 78% of patients with OSA responded that they “would never doze” to it.

Given the poor performance of item 8, replacement of it with more reliable item is necessary. As a result of this substitution, the mESS not only improved the internal validity (increased Cronbach’s alpha) but also congregated the measurement into one dimension, i.e., EDS. It was just what the original one did while applied to Australian patients [11]. When constructing the mESS, we chose item 10 instead of item 9 in the 10-ISQ to replace item 8 in the original ESS, because item 10 had contributed slightly more than item 9 to the principal measurement of the 10-ISQ.

The mESS scores seemed to be capable of discerning the severity of OSA (Table 3). The interpretability of mESS to score change was good and comparable to an investigation based on a validated German version of ESS [10]; alleviation of sleep apnea by nasal CPAP treatment led to significant reduction in the scores in both studies.

The discovery that our subjects’ mESS scores correlated only to the frequency of apneas and hypopnea (R2 = 0.50, P < 0.001) by multiple linear regression is very similar to what Jones found (R2 = 0.23, P < 0.001) [19], except for the higher coefficient of correlation in our study. Sampling bias might be one of the reasons for this discrepancy. Our patients were much more severe: 64% OSA patients in our study had AHI more than 25 h−1, compared to just 36% in Jones’s study. We postulate that the more severe OSA a patient suffers, the less likely his or her EDS is contributed by confounding factors or overlapping comorbidities.

However, the mESS is not reliable for normal subjects because of low internal consistency and more than one measurement dimension (Tables 1, 2). The studies based on Australian [11], German-speaking Swiss [10], and Hong Kong Chinese [12] also indicated that the internal consistency of the ESS as applied to normal subject was inferior to that for patients (Cronbach’s alphas of normal subjects vs. SDB patients were 0.73 vs. 0.88, 0.60 vs. 0.83, and 0.69 vs. 0.80, respectively) implying the irrelevancy of this questionnaire to subjects without EDS. Although the Australian study obtained an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha (0.73) for the medical students, the students could not be regarded as normal. They were more sleepy (ESS 7.6 ± 3.9) than the healthy Australian subjects (ESS 5.9 ± 2.2) in another investigation [1, 11].

We conclude that not only is the modification of ESS necessary, but also that the mESS improves the validity of ESS in assessment of EDS for patients with SDB in central China.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry. We are grateful to Mr. Dave Carini and Ms. Oloo Stella Anne for their assistance on revision of this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- AHI

Apnea and hypopnea index

- CPAP

Continuous positive airway pressure

- EDS

Excessive daytime sleepiness

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- mESS

Modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

- SpO2 < 90

Percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation below 90%

- SDB

Sleep-disordered breathing

- 10-ISQ

Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire

Appendix

Ten-item Sleepiness Questionnaire and its Chinese translation (in parenthesis) *

How likely are you to doze off or fall asleep in the following situations, in contrast to feeling just tired? This refers to your usual way of life in recent times. Even if you have not done some of these things recently, try to work out how they would have affected you. Use the following scale to choose the most appropriate number for each situation (请根据您近期的通常状况,参照以下的"自我评分办法",评价自己白天在下列10种情况下,是否有打瞌睡或入睡(而不是仅仅感到疲劳)的可能性,如近期没有经历以下列举的某些情景,也请想象在那样的情况下,您可能会受到的影响).

0 –no chance of dozing(完全不会打瞌睡)

1–slight chance of dozing(偶尔打瞌睡)

2–moderate chance of dozing(一半会打瞌睡)

3–high chance of dozing (很可能会打瞌睡)

| Situation (情景) | Chance of dozing (打瞌睡的机会) |

|---|---|

| Sitting and reading(坐着阅读时) | |

| Watching TV(看电视时) | |

| Sitting inactive in a public place (e.g., a theater or a meeting) [在公共场所平静坐着时(如在剧场或会场)] | |

| As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break (作为乘客连续坐车超过1小时) | |

| Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit(下午有空能躺下休息时) | |

| Sitting and talking to someone (坐着与人交谈时) | |

| Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol(未饮酒的午餐后静坐休息时) | |

| In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic(开车中因交通问题停下数分钟时) | |

| When sitting and playing a game, such as mahjong, poker, or chess (白天坐下进行诸如扑克、麻将等娱乐活动时) | |

| When working or studying in the late afternoon or in the early evening on the days without an after-lunch nap(没午睡,在当天下午、傍晚进行工作和学习时) |

* Epworth Sleepiness Scale includes items 1–8; mESS includes items 1 ~ 7 and 10

References

- 1.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chica-Urzola HL, Escobar-Cordoba F, Eslava-Schmalbach J. Validating the Epworth sleepiness scale. Review Salud Publication (Bogota) 2007;9:558–567. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642007000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izci B, Ardic S, Firat H, et al. Reliability and validity studies of the Turkish version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breath. 2008;12:161–168. doi: 10.1007/s11325-007-0145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen AT, Baltzan MA, Small D, et al. Clinical reproducibility of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2006;2:170–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeZee KJ, Jackson JL, Hatzigeorgiou C, Kristo D. The Epworth sleepiness scale: relationship to sleep and mental disorders in a sleep clinic. Sleep Medicine. 2006;7:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gander PH, Marshall NS, Harris R, Reid P. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: influence of age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation. Epworth Sleepiness scores of adults in New Zealand. Sleep. 2005;28:249–253. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsara V, Serasli E, Amfilochiou A, et al. Greek version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breath. 2004;8:91–95. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-829632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Barbato A, et al. Italian version of the Epworth sleepiness scale: external validity. Neurology Science. 2003;23:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s100720300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiner E, Arriero JM, Signes-Costa J, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in patients with a sleep apnea syndrome. Archivos de Bronconeumologia. 1999;35:422–427. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2896(15)30037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloch KE, Schoch OD, Zhang JN, Russi EW. German version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration. 1999;66:440–447. doi: 10.1159/000029408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15:376–381. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung KF. Use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnea and normal hospital employees. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2000;49:367–372. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen NH, Johns MW, Li HY, et al. Validation of a Chinese version of the Epworth sleepiness scale. Quality of Life Research. 2002;11:817–821. doi: 10.1023/A:1020818417949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tachibana N, Taniguchi M. Why do we continue to use Epworth sleepiness scale? Sleep Medicine. 2007;8:541–542. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumru H, Santamaria J, Belcher R. Variability in the Epworth sleepiness scale score between the patient and the partner. Sleep Medicine. 2004;5:369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SS, Oei TP, Douglas JA, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Medicine. 2008;9:739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herdman M, Fox-Rushby J, Badia X. A model of equivalence in the cultural adaptation of HRQoL instruments: the universalist approach. Quality of Life Research. 1998;7:323–335. doi: 10.1023/A:1008846618880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns MW. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest. 1993;103:30–36. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]