Abstract

Background

The role of acute phase cytokines generated in the nasopharynx during viral upper respiratory infection (URI) in subsequent development of acute otitis media (AOM) has not been examined.

Methods

We studied 326 virus-positive URI episodes in 151 children of age 6–36 mos. Nasopharyngeal secretions (NPS) collected within 1–7 days of URI onset were studied for viruses by conventional and molecular techniques, and for concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα by multiplex ELISA. Children were followed for 28 days to document AOM complication.

Results

IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα concentrations correlated positively with each other (P<0.001). IL-6 and TNFα concentrations were higher in males than females (P = 0.01 and 0.02). IL-6 and TNFα concentrations were inversely correlated with age (P = 0.02 and 0.05). IL-6 concentrations correlated positively with duration of fever (P = 0.006) and correlated negatively with the number of days of URI symptoms (P = 0.026). Furthermore, IL-6 concentrations were significantly higher during adenovirus and influenza virus URIs as compared with enterovirus and rhinovirus URIs (P<0.01). IL-1β concentrations were higher during URI episodes with AOM than those without AOM (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

We found IL-6 NPS concentrations to be higher with adenovirus and influenza infection, and in children with systemic febrile response during URI. However, IL-1β was found to play a more important role in the development of AOM following URI. Additional studies are needed to further define the role of acute phase cytokines in virus-induced AOM.

Keywords: acute otitis media, acute phase cytokines, upper respiratory tract infection

INTRODUCTION

Various studies have shown that 10–50% of young children with viral URI develop acute otitis media (AOM) (1). Despite the well-known role of viruses in causation of AOM, the mechanisms of differential risks of AOM with different viruses remain poorly defined.

During acute viral URI, several cytokines and other inflammatory molecules are found in the nasal secretions of children (2–6), suggesting that these cytokines participate in the regulation of virus-induced inflammation and/or recovery from the infection. IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α are found in significant quantities during viral URI (2–6) and considered to be the key cytokines that regulate the acute phase of the inflammatory response.

We have previously shown the relationship between high cytokine-inducing single nucleotide polymorphic (SNPs) genotypes, namely IL- 6-174 and TNFα-308, and susceptibility to recurrent AOM (7). It is possible that the enhanced cytokine production in the nasopharynx during viral URI plays a role in the intricate cascade of host responses leading to increased or prolonged inflammatory responses during URI and development of complications such as AOM. However, the risk of AOM development in relation to cytokine production in the nasopharynx during the preceding viral URI has previously not been reported.

In the present study, we performed quantitative measurements of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα in the nasopharyngeal secretions (NPS) during URI episodes, and correlated them with the virus etiology, host factors, and development of AOM.

METHODS

(i) Clinical evaluation

This was a sub-cohort study of virus-positive URI episodes in children who were enrolled in a prospective, longitudinal study of the incidence and characteristics of AOM complicating URI in children (8). The study was performed at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston and was approved by the UTMB Institutional Review Board. Children were recruited from the primary care pediatrics clinics at UTMB, Galveston. Children were otherwise healthy at enrollment. Children with anatomic and physiologic defect of the nasopharynx or ear (including tympanostomy tubes), or with major medical condition were excluded.

Children were enrolled from 6 mos. to 3 yrs. of age. Each child was followed for one year for occurrences of URI and AOM. Children were seen by a study physician as soon as possible after the onset of URI symptoms (nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, cough, and/or sore throat with or without fever) and then followed again a few days later (days 3–7 in the course) for complications. Home tympanograms were performed in the second and third weeks of URI. Parents were advised to bring the child for examination whenever they suspected the child to have any symptom of AOM.

AOM complicating URI was considered when the episode occurred within 28 days of the onset of URI unless a new URI occurred within this period; in that case, AOM was considered the complication of the most recent URI episode. AOM was defined by acute onset of symptoms (fever, irritability, or earache), signs of tympanic membrane inflammation and presence of fluid in the middle ear documented by pneumatic otoscopy and/or tympanometry. Children diagnosed with AOM were observed or given antibiotic therapy consistent with standard of care.

(ii) Sample collection

NPS samples were collected from children at the initial visit for each URI episode. NPS samples for viral studies were collected by swabs and sent immediately for virus isolation. NPS samples for cytokine analysis were collected by vacuum suction and specimen traps. After the suction, additional 1 ml of sterile phosphate-buffered saline was aspirated through the suction tubing to collect the residual amount coated on the inner parts of the tubing; the volume of diluted secretions was then measured for calculation of the dilution factor. Aliquots of NPS were stored at −70° C until used for quantitative cytokine analysis.

(iii) Virologic Studies

Viral isolation was performed in the Clinical Virology Laboratory at UTMB using standard tissue culture methods; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) antigen detection was done by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) in the laboratory of the investigators (performed at UTMB only during RSV season). NPS samples from the initial URI visit that were negative by culture and RSV-EIA techniques were further studied by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques in the laboratory of Dr. Kelly J. Hendrickson at the Medical College of Wisconsin as previously described (8). For detection of adenovirus, rhinovirus and enterovirus, individual real-time PCR was used; for RSV, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3 and influenza virus A and B, real time-PCR with electronic microarray detection (NanoChip® 400 system) was performed as described previously (9–10).

(iv) Quantitative Cytokine Analysis

Concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα in NPS samples from the initial visit of all virus-positive URI episodes were measured by multiplex ELISA (BioSource kit,® Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA) on Luminex™ 100 platform (Luminex Corp, Austin, TX). An internal range of standards was used to establish the standard curve and to define the upper and lower detection limits of cytokine concentrations at each run. The lowest detection limit of the assay was <10 pg/ml for IL-6 and TNFα, and <5 pg/ml for IL-1. All samples that were above the upper range of calculation were further diluted until within the range of assay. All NPS samples were processed in duplicate, the average value of cytokine was used for analysis. Final concentrations of cytokines were standardized with the dilution factor and reported in pg/ml of the undiluted NPS.

(v) Statistical Analysis

The statistical approaches to data analysis accounted for multiple episodes of URI (as many as eight) which result in clusters of correlated data from each subject. We used a class of models called general linear mixed models (GLMM) utilizing general estimating equations (GEE) for parameter estimation. Parameter estimates and P values were derived from the GENMOD procedure in SAS® specifying a normal distribution with an AR(1) working correlation structure.

Our GLMM was fit specifying a normal distribution and assumes that the outcome variables follow an approximate normal distribution. Cytokine data, however, tends to be skewed away from normality in the direction of larger values. A natural log transformation was used for all IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα values as the bases of all statistical procedures. The natural logs of the cytokines resulted in distributions that better meet the assumption of an approximate normal distribution. The means and standard errors in Tables 3, 4 and 5 were back transformed from model generated estimates and least squares means.

Table 3.

Cytokine concentrations in nasopharyngeal secretions by fever and acute otitis media (AOM) status at initial evaluation of 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children

| IL-1β Mean ± SE pg/ml |

P value | IL-6 Mean ± SE pg/ml |

P value | TNFα Mean ± SE pg/ml |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever a | ||||||

| Yes | 502 ± 75 | 0.32 | 2,704 ± 325 | <0.001 | 939 ± 125 | 0.06 |

| No | 398 ± 80 | 1,231 ± 179 | 659 ± 101 | |||

|

| ||||||

| AOM b | ||||||

| Yes | 695 ± 64 | <0.001 | 2,200 ± 384 | 0.20 | 959 ± 140 | 0.15 |

| No | 356 ± 115 | 1,705 ± 203 | 717 ± 102 | |||

Presence of fever on the day of sample collection;

AOM development within 28 days of onset of URI symptoms;

Mean values shown above were derived by back-transformation of natural log data as described in Methods. The general estimating equation approach was used for analysis of log transformed data. This model took into account multiple episodes of URI in the same child;

SE = standard error.

Table 4.

Cytokine concentrations in nasopharyngeal secretions by virus type at initial evaluation of 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children

| Virus Type | Episodes N (%)a |

IL-1β Mean ± SE pg/ml |

IL-6 Mean ± SE pg/ml |

TNFα Mean ± SE pg/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhinovirus | 94 (29) | 406 ± 105 | 1,348 ± 241 | 673 ± 125 |

| Adenovirus | 83 (25) | 505 ± 127 | 3,196 ± 712b | 1,130 ± 237 |

| Enterovirus | 51 (16) | 273 ± 89 | 1,044 ± 274 | 558 ± 142 |

| Parainfluenza virus | 36 (11) | 402 ± 105 | 1,964 ± 533 | 739 ± 211 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 35 (11) | 829 ± 227 | 1,472 ± 433 | 963 ± 283 |

| Influenza virus | 27 (8) | 621 ± 235 | 4,152 ± 1,233c | 838 ± 215 |

Figures in parenthesis represent percent of column total;

Adenovirus > enterovirus and rhinovirus, P = 0.005 and 0.008, respectively;

Influenza > enterovirus and rhinovirus, P = 0.007 and 0.018, respectively;

Mean values shown above were derived by back-transformation of natural log data as described in Methods. The general estimating equation approach was used for analysis of log transformed data. This model took into account multiple episodes of URI in the same child;

SE = standard error.

Table 5.

Comparison of nasopharyngeal cytokine concentrations by virus detection methods at initial evaluation of 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children

| Culture and RSV Antigen Positive Samples (n = 173) | PCR-Positive Samples (n = 153) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | Mean ± SE pg/ml | Mean ± SE pg/ml | P value |

| IL-1β | 679 ± 87 | 281 ± 70 | 0.002 |

| IL-6 | 2,243 ± 305 | 1,507 ± 229 | 0.05 |

| TNFα | 751 ± 88 | 849 ± 158 | 0.57 |

P values comparing cytokine concentration with virus type were calculated after natural log transformation of data, and by using general estimating equation approach which took into account multiple episodes of URI in the same child;

Mean values shown above were derived by back-transformation of natural log data as described in Methods;

SE = standard error;

PCR = polymerase chain reaction;

RSV = respiratory syncytial virus.

Table 1 and Figure 1 present episodes-level descriptive statistics of the original distributions of the cytokine concentrations prior to log transformation for all episodes of URI. In Table 2, Pearson correlations are reported for the last URI episode for each child; this approach was taken since the correlation test cannot be performed on multiple-episode data from the same child. In Table 6, for the test of association of each cytokine with AOM development adjusting for other predictors, we used GLMM with parameter estimation based on GEE to account for the inherent correlation that occurs when multiple episodes of data are contributed from the same child. All P values were considered significant at 0.05.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of cytokine concentrations in nasopharyngeal secretions at initial evaluation of 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection in 151 children

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | IL-6 (pg/ml) | TNFα pg/ml | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range (min – max) | 2.8 – 289,829 | 3 – 91,839 | 0.28 – 19,994 |

| Median | 2,049 | 816 | 615 |

| Mean | 1,751 | 6,806 | 3,024 |

| Standard deviation | 2,807 | 18,829 | 8,246 |

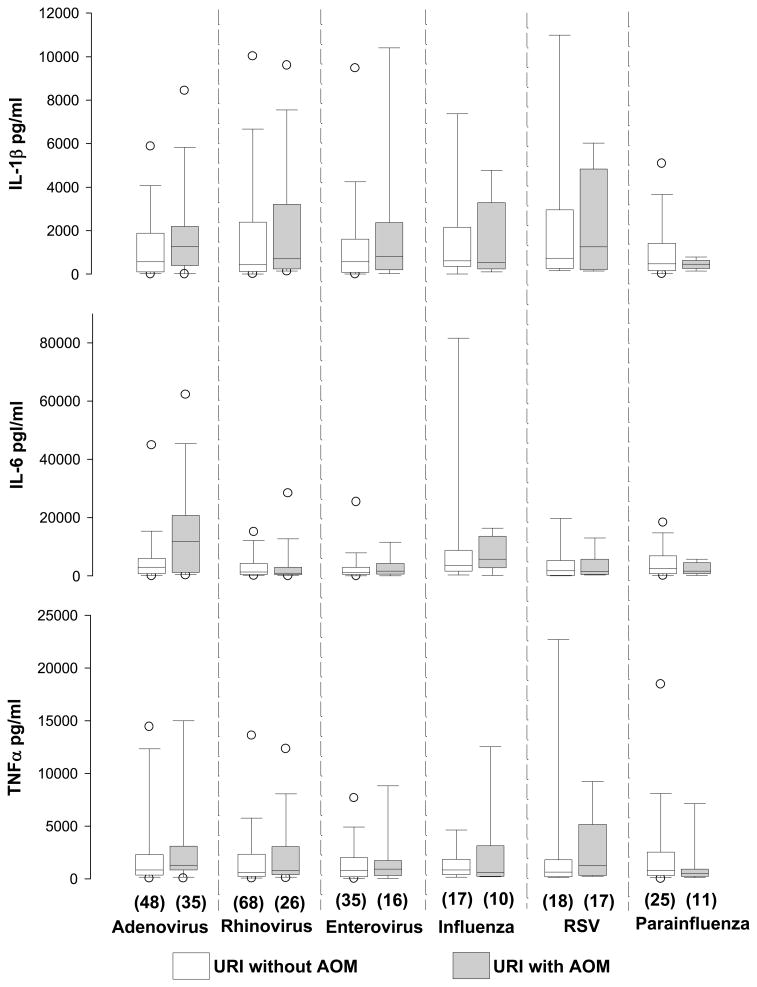

Figure 1.

Comparison of cytokine concentrations with respect to development of acute otitis media (AOM) in relation to various viral pathogens at initial evaluation of 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children

Above box plot graphs the percentiles and the median of column data. The ends of the boxes define the 25th and 75th percentiles, with a line at the median and error bars defining the 10th and 90th percentiles. The open circles define 5th and 95th percentiles.

Table 2.

Correlation of clinical factors with nasopharyngeal cytokine concentrations in the last episode of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children

| Log IL-1β | Log IL-6 | Log TNFα | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | r = 0.47 | r = 0.72 | |

| P <0.001 | P <0.001 | ||

| IL-6 | r = 0.62 | ||

| P <0.001 | |||

| Age (mos) | r = −0.08 | r = −0.19 | r = −0.16 |

| P = 0.32 | P = 0.02 | P = 0.05 | |

| Fever duration (days) | r = −0.01 | r = 0.224 | r = 0.09 |

| P = 0.93 | P = 0.006 | P = 0.29 | |

| Day of URI (days) | r = −0.05 | r = −0.18 | r = −0.13 |

| P = 0.54 | P = 0.03 | P = 0.12 |

Above Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated after natural log transformation of the cytokine concentration values (pg/ml). The last URI episode data was used in order to account for multiple episodes in the same child;

r = Pearson correlation coefficient

Table 6.

Statistical prediction of each cytokine using GLMMa, and including all 326 episodes of upper respiratory infection (URI) in 151 children.

| Variable | DF | Log IL1-β P value |

Log IL-6 P value |

Log TNFα P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus type b | 5 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Acute otitis media developed (Yes) | 1 | 0.046 | 0.88 | 0.20 |

| Age (mo) | 1 | 0.91 | <0.001 | 0.60 |

| Gender (Male) | 1 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Race/ethnicity (Caucasian, Hispanic, Asian, Black) | 3 | 0.68 | 0.04 | 0.46 |

GLMM = general linear mixed model. GLIMM analysis accounted for multiple episodes of URI per child with parameter estimation based on general estimating equation approach. The analysis was conducted after natural log transformation of the cytokine concentration values (pg/ml);

Virus types analyzed were adenovirus, enterovirus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus; DF = degrees of freedom.

RESULTS

(i) Relationship with Demographic and Clinical Factors

Between January 2003 and March 2006, 294 children were enrolled who had a total of 1295 episodes of URI, 867 of which were evaluated by the study team. Included in this cytokine study were NPS samples from 326 episodes of URI in 151 children that were confirmed to have single virus associated with new URI episode. The studied NPS samples were collected within seven days of onset of URI (mean = 3.7 days). Samples with multiple viruses detected were not included in the analysis because our main objective was to study the effect of individual viruses on cytokine production and disease manifestation.

The range of URI episodes in this cohort was 1–8 episodes per child. The mean age of the children at URI episodes was 19.6 mos (median = 18.3 mos, range = 6 to 46 mos). There were 73 (48%) males; the ethnic/racial distributions were 63 (42%) Hispanics, 43 (28%) blacks, 34 (23%) Caucasians, 6 (4%) Asians, and 5 (3%) of mixed races. The cohort of children with single positive virus in NPS included in this analysis was not different from the overall study population for gender and ethnicity/race, but were found to be older (mean age 19.6 mos versus 13.7 mos).

The descriptive statistics of cytokine concentrations are shown in Table 1. All NPS samples contained detectable amounts of cytokines. In Table 2, we show correlations of cytokine concentrations with each other, age, and duration of fever and URI symptoms at the time of NPS collection for the last episode of URI in each child. When the correlation tests were performed on data from the initial episodes of URI, similar results were noted. All three cytokine concentrations correlated positively with each other. IL-6 and TNFα concentrations were inversely correlated with age. IL-6 concentrations were also inversely correlated with the number of days of URI symptoms. Furthermore, the concentrations of IL-6 were positively correlated with the duration of fever prior to NPS collection (Table 2), and were significantly higher when the children had fever on the day of NPS collection (Table 3).

(ii) Relationship with AOM Development and Virus Type

One hundred and fourteen (35%) URI episodes were associated with AOM development. Higher mean concentrations of IL-1β were associated with higher rate of AOM (Table 3). The overall concentrations of IL-6 and TNFα were not significantly different when comparing the presence/absence with AOM. Figure 1 displays the levels of cytokines in relation to the virus type and AOM development. Using GEE model accounting for multiple episodes of URI in the same child, the association of IL-1β with AOM development was found not to be due to any specific virus.

Table 4 shows the concentrations of all three cytokines by virus type. Influenza and adenovirus infections were associated with significantly higher mean concentrations of IL-6 in NPS when compared to rhinovirus and enterovirus infections. The concentrations of IL-1β and TNFα were not associated with any specific virus type. We also compared the concentrations of cytokines in relation to the method of virus detection. The mean concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly higher in NPS samples with viruses identified by conventional culture and antigen detection tests as compared with PCR tests (Table 5).

(iv) Analysis of Independent Predictors

Table 6 shows the test of independent association of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and AOM development with cytokine concentrations. The virus type (influenza), age and Caucasian race independently predicted higher concentrations of IL-6, AOM predicted higher concentrations of IL-1β, and male gender predicted higher concentrations of IL-6 and TNFα.

DISCUSSION

While the acute phase cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα have previously been detected in the NPS during URI due to a variety of viruses (2–6), the relationship of these cytokines in NPS with the risk of developing AOM during or after URI has not been reported previously. Whether these cytokines are simply mediators of acute of inflammation in URI or play an important role in the pathogenesis of AOM complicating URI is not clear. In the present study, we show that during URI, all of the viruses induced significant quantities of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα which correlated with each other; this suggests a common pathway in acute inflammation during viral URI. To our knowledge, the present study represents the largest number of virus-confirmed episodes of URI examined for acute phase cytokines.

Our data also show an independent association between high concentrations of IL-1β in NPS and increased rate of AOM development. The role of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of AOM requires further exploration. Possible mechanisms by which this cytokine can promote AOM during URI include neutrophil activation and chemokine production, which in turn cause local tissue edema leading to Eustachian tube blockage and bacterial invasion of the middle ear. While Gentile et al reported in a study of adult volunteers that intranasal administration of recombinant IL-6 led to increased production of nasal secretions and decreased Eustachian tube function (11), similar studies of topical effects of IL-1β are lacking. IL-1β can act through increasing the expression of IL-6 and several other cytokines (12). The acute phase cytokines may also play a beneficial role in the pathogenesis of AOM as well; Lindberg et al showed that the NPS concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly lower in children with history of recurrent AOM (13), suggesting that a robust cytokine response may enhance immune responses that protect against recurrent episodes of AOM. However, these investigators did not evaluate the NPS cytokine levels during episodes of viral URI or AOM.

In our study, high concentrations of IL-6 were associated with the presence of fever at and prior to NPS collection. Fever may be a marker of severity of local and systemic inflammation. Previous studies have shown a relationship between concentrations of IL-6 and clinical course of URI. For example, in a study of experimental influenza virus infection, duration of virus shedding was associated with concentrations of IL-6 and TNFα in nasal secretions, and the concentrations of these cytokines were associated with increased local and systemic symptoms, including fever (14). IL-6 can mediate these inflammatory effects by induction of C-reactive protein synthesis, promoting neutrophil aggregation, activation and apotosis, enhancing production of chemokines, and regulation of T cell adhesion (15). However, in the present study, despite the association of IL-6 concentrations in NPS with systemic febrile response, its effect on the development of AOM was not observed. The lack of association of IL-6 and TNFα with AOM does not exclude their potential role in the pathogenesis of AOM as the levels of these cytokines in NPS had large variability and the time of NPS collection during URI episode was not standardized. Furthermore, these cytokines could exert their actions in the intricate cascade of cytokine network. Overall, our study suggests that IL-6 and TNFα are more involved in systemic responses such as fever, while IL-1β is more involved in the local nasopharyngeal inflammation that leads to AOM.

Differential production of cytokines in the nasopharynx by different respiratory viruses has been described previously (2–6), but these studies have either examined fewer viruses, fewer URI episodes, or have studied children who have complications of the lower airway following URI; none have studied the NPS cytokines in the context of AOM. We show that viruses such as adenovirus and influenza induce high concentrations of IL-6 when compared with rhinovirus or enterovirus. However, whether the virus-specific differences in AOM development are due to the differences in concentrations in acute phase cytokines could not be confirmed in the present study; this may require a larger prospective study that includes determination of the relative quantity of virus in NPS. Our study also did not take into account the effect of local virus-bacteria interactions on cytokine concentrations in NPS; this requires further study.

Another interesting observation of our study was that IL-1β and IL-6 concentrations in NPS samples that contained viruses detected by conventional methods were substantially higher than when the viruses were detected by the more sensitive PCR (ie. require lower virus quantity for detection). We used the PCR method for NPS samples that were negative for viruses by conventional methods, although the types of viruses evaluated by PCR were the same types that could potentially be identified by conventional methods. Our results therefore suggest that the samples identified by the PCR technique contained relatively low concentrations of infectious viruses, which in turn lead to the reduced production of cytokines. While this observation needs further study using quantitative virologic techniques, previous studies suggest that virus quantity can affect cytokine concentrations. For example, Sheeran et al have shown that nasal wash RSV concentrations correlate with nasal wash concentrations of IL-6 and all other cytokines and chemokines measured (4).

The independent association of high concentrations of IL-6 and TNFα cytokines with male gender in our study was surprising as this has not been reported previously in children with URI. Whether the high cytokine concentrations in NPS correlate with the known high risk of AOM in males (16) is not clear, although this is plausible. In a study of pediatric burn patients, serum concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 were significantly higher in males; males also had more prolonged intensive care and higher muscle protein loss than females (17). In our study, IL-6 concentrations were also higher in Caucasian children. While there are many studies of variable distributions of cytokine gene polymorphisms in various races/ethnic groups, there very few studies of cytokine concentrations analyzed by race/ethnicity in children and adults. Ryckman et al reported that Caucasian women with bacterial vaginosis had significantly higher cervical concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 than blacks (18). Thus, some of the gender and race/ethnicity specific differences in disease burden may be explained by differences in cytokine responses.

In summary, our study highlights the role of respiratory viruses in induction of acute phase cytokines in the nasopharynx and their role in AOM development. While only IL-1β concentrations in NPS were associated with the AOM during URI episode, we cannot exclude the potential role of IL-6 and TNFα as cytokines work together in a complex network. Additional studies are needed to investigate the interaction between viruses and nasopharyngeal bacterial flora on cytokine production, the mechanism by which specific viruses interact with the cytokine network and other arms of the immune system, and the role of host cytokine gene polymorphisms in regulation of respective cytokines in the nasopharynx.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DC005841 and DC 005841-02S1. The study was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Texas Medical Branch, which is funded by National Center for Research Resources (National Institutes of Health, US Public Health Service) grant M01 RR 00073.

We thank M. Lizette Rangel, Kyralessa B. Ramirez, Syed Ahmad, Michelle Tran, Liliana Najera, Rafael Serna and Carolina Pillion for assistance with study subjects.

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 DC 5841 (to T.C.) The study was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, funded by grant M01 RR 00073 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH, USP.

References

- 1.Heikkinen T, Chonmaitree T. Importance of respiratory viruses in acute otitis media. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:230–41. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.230-241.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noah TL, Henderson FW, Wortman IA, et al. Nasal cytokine production in viral acute upper Respiratory infection of childhood. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:584–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung RY, Hui SH, Wong CK, Lam CW, Yin J. A comparison of cytokine responses in respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A infections in infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:117–22. doi: 10.1007/s004310000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheeran P, Jafri H, Carubelli C, Saavedra J, Johnson C, Krisher K, Sánchez PJ, Ramilo O. Elevated cytokine concentrations in the nasopharyngeal and tracheal secretions of children with respiratory syncytial virus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:115–22. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199902000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitrez PM, Brennan S, Sly PD. Inflammatory profile in nasal secretions of infants hospitalized with acute lower airway tract infections. Respirology. 2005;10:365–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2005.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laham FR, Israele V, Casellas JM, Garcia AM, Lac Prugent CM, Hoffman SJ, Hauer D, Thumar B, Name MI, Pascual A, Taratutto N, Ishida MT, Balduzzi M, Maccarone M, Jackli S, Passarino R, Gaivironsky RA, Karron RA, Polack NR, Polack FP. Differential production of inflammatory cytokines in primary infection with human metapneumovirus and with other common respiratory viruses of infancy. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:2047–56. doi: 10.1086/383350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel J, Nair S, Revai K, Grady J, Kokab S, Matalon R, Block S, Chonmaitree T. Association of proinflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to otitis media. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chonmaitree T, Revai K, Grady JJ, Clos A, Patel JA, Nair S, Fan J, Henrickson KJ. Viral upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media complication in young children. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:815–23. doi: 10.1086/528685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan J, Henrickson KJ, Savatski LL. Rapid simultaneous diagnosis of infections with Respiratory Syncytial Viruses A and B, Influenza Viruses A and B, and Human Parainfluenza Virus Types 1, 2, and 3 by multiplex quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction-enzyme hybridization assay (Hexaplex) Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1397–1402. doi: 10.1086/516357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henrickson KJ, Kraft A, Shaw J, Canter D. Comparison of electronic microarray (NGEN RVA) to enzyme hybridization assay (Hexaplex) for multiplex RT-PCR detection of common respiratory viruses in children. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter (Elsevier) 2007;29(15):113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentile DA, Yokitis J, Angelini BL, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP. Effect of intranasal challenge with interleukin-6 on upper airway symptomatology and physiology in allergic and nonallergic patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86:531–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1beta. Crit Care Med. 2005;33 (Suppl):S460–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000185500.11080.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindberg K, Rynnel-Dagöö B, Sundqvist KG. Cytokines in nasopharyngeal secretions; evidence for defective IL-1 beta production in children with recurrent episodes of acute otitis media. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;97:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser L, Fritz RS, Straus SE, Gubareva L, Hayden FG. Symptom pathogenesis during acute influenza: interleukin-6 and other cytokine responses. J Med Virol. 2001;64:262–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones SA. Directing transition from innate to acquired immunity: defining a role for IL-6. J Immunol. 2005;175:3463–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teele DW, Klein JO, Rosner B. Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:83–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeschke MG, Mlcak RP, Finnerty CC, Norbury WB, Przkora R, Kulp GA, Gauglitz GG, Zhang XJ, Herndon DN. Gender differences in pediatric burn patients: does it make a difference? Ann Surg. 2008;248:126–36. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176c4b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Racial differences in cervical cytokine concentrations between pregnant women with and without bacterial vaginosis. J Reprod Immunol. 2008;78:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]