Abstract

Background:

There is a great deal of studies on the relationship between the existence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in oral cavity (dental plaque) and in stomach of patients, with conflicting results worldwide. The purpose of this study was to systematically review the existing litreature to assess if the dental plaque could be a source of gastric H. pylori infection and to explore the source of heterogeneity around it.

Methods:

We searched all the papers published since 2000 on international (Medline, ISI, Embase) databases using standard keywords. Two researchers evaluated the articles with standard critical appraisal form independently and those articles with the quality acquired greater than 70% were included in the study. The combined results were calculated with weighted average and the source of hetrogeneity was tested by meta-regression (random) model.

Results:

Finally, 23 studies were included (1861 patients). The prevalence of co-infection of gastric and dental plaque H. pylori was 49.7% (95% CI 16–83.4%) and the percent of agreement between the dental plaque H. pylori status and the gastric H. pylori was estimated as 82%. Only one study has reported that dental treatment has a preventive effect on the recurrence of gastric H. pylori infection.

Conclusion:

Co-infection of gastric H. pylori and dental plaque is reported by half of the studies. However, there is not enough evidence for the efficacy of dental treatment on prevention of recurrent gastric H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, meta-analysis, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is known as a risk factor for chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer.[1,2] H. pylori infection is one of the most common bacterial infections in humans,[3,4] and on an average, 50% of people in the world are infected by this microorganism.[5–7] This digestive infection is successfully curable by systematic antibiotic therapy and can be highly (up to 80–90%) eradicated after a therapeutic period called “Triple Therapy”.[4,7,8] However, this infection can be observed again in people who have been previously treated and this reappearance is a very challenging obstacle concerning peptic ulcer treatment.[9,10] Thus, the hypothesis arises that this microorganism remains in some parts of patients′ bodies as a re-colonization etiology.[1,6] Observing H. pylori in patients′ saliva, tongue dorsum and dental plaque, many researchers introduced the mouth cavity as a suitable place for H. pylori and thus recurrence of gastric infection.[9,10] Since dental plaque can create an ideal micro-aerophilic environment and can form a matrix of glycolproteins for reproduction and protection of microbial population, it is regarded as the most probable place for H. pylori;[8] it is likely that when H. pylori goes to this place, it can be immune to antibiotics and can cause the gastric infection to return. However, in various studies, inconsistent results have been reported concerning the appearance of H. pylori in dental plaque.[3] Therefore, the question, “can mouth cavity act as a store for this pathogen?” has remained unanswered. Although a series of studies have reported the simultaneous appearance of H. pylori in mouth and stomach samples of patients, other attempts have failed to find H. pylori in the mouth of patients with gastric infection.[1,2,7–9]

Based on the litreture review on H. pylori in dental plaque and its relation to peptic ulcer, we found that the results are somehow heterogenous and mainly inconsistent. So, we decided to systematically review the existing evidence to assess if the dental plaque could be a source of gastric H. pylori infection and to explore the sources of heterogeneity around it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Searching

The present study was a systematic review and meta-analysis. All articles published in Farsi or English from January 2000 to December 2008 were reviewed. To do this , ISI web of science, EMBASE and Medline Digital Library Electronic Databases were used. In this case, the medical keywords of Helicobacter, Helicobacter pylori and H. pylori were searched in combination with the words Dental plaque, Dyspepsia, Peptic ulcer and gastritis. In addition, summaries of all articles presented in congresses were used. After searching the electronic resources, we started searching non-electronic resources including all handbooks presented in seminars related to mouth health. References of the papers found were used for finding other related papers.

Selection

All related original articles published during the above-mentioned period in the Farsi or English language were reviewed. The outcome was the H. pylori testing results in both dental plaque and the stomach.

Paper selection and data extraction

All the selected articles and studies were separately and critically analyzed by two researchers. To do this, they used a standard checklist according to Cochrane site guide to evaluate the main characteristics of these studies like sampling method and reliability of evaluations (www.equator-network.org). Therefore, the articles which could not obtain the minimum quality score (8 out of 14) were excluded. Also, studies that reported some special cases or a special diagnostic technique instead of studying the given relationship were excluded too. In case these two researchers did not agree about accepting or rejecting the quality of an article, a third researcher made the final decision.

Quantitative data synthesis

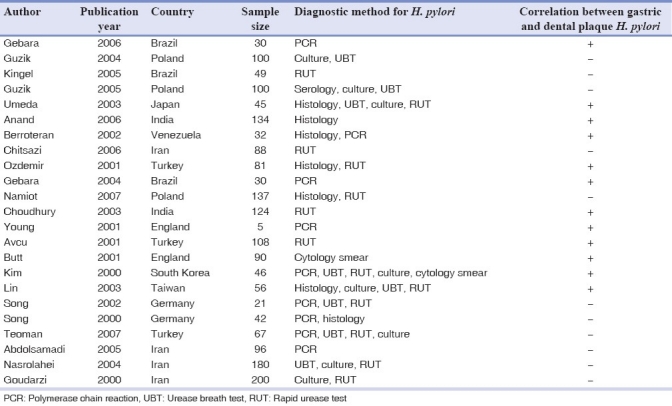

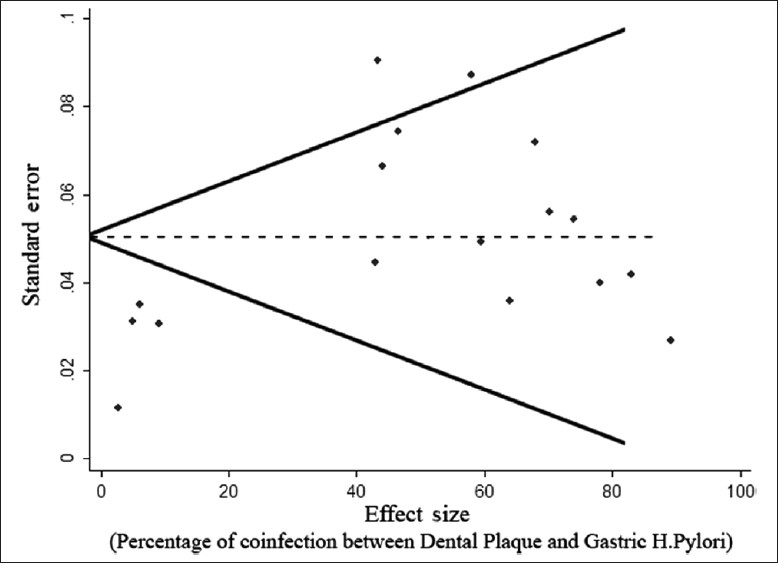

Data from the well-qualified studies were extracted into an Excel worksheet. Publication year, research location, sample size, diagnostic methods and the percentage of co-infection were calculated [Table 1]. As the results were significantly heterogeneous, we calculated the random effect confidence interval 95% in Stata v. 10. Sex, age and diagnostic method were tested in meta-regression of being as a possible source for publication bias. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot illustration [Figure 1].

Table 1.

The description of studies that met our eligibility criteria

Figure 1.

Funnel plot for the association between the reported effect size and the standard error in each study

RESULTS

Finally, 23 articles (20 English and 3 Farsi) were included in the study.[1–23] The study by Chitsazi et al,[9] was conducted in Iran but published in an English language Journal. All studies were critically appraised. All articles were reviewed and data were extracted and stratified. The details of the 23 studies are shown in Table 1. The average correlation coefficient between the reviewers was (0.9). The total quality score of each study was calculated but was not significant. The results of 12 articles showed a significant correlation between the occurrence of H. pylori in the stomach and in the oral cavity. Generally, the aggregated data of 1861 patients were reviewed. In five studies, results were not reported by sex. In other 18 studies, totally 745 male and 790 female patients were studied; their ages varied between 9 and 90 years, and the average age was 42.8±7.4 years. Co-infection of H. pylori in dental plaque and stomach was estimated as 49.7% (95% CI 16–83.4%). Only 32.3% (95% CI 0.1–73%) of the reported cases were infected whether by dental plaque or gastric H. pylori. H. pylori was diagnosed in 37.2% (95% CI 33.5–49.9%) of patients only in stomach but not in dental plaque (33.5–49.9%). H. pylori was diagnosed in 24.7% (95% CI 21.3–28.0%) of patients only in dental plaque. The percent of agreement between the dental plaque H. pylori status and the gastric H. pylori was estimated as 82% (range of 16–100%).

The meta-regression coefficient of the relationship between age and the percentage of infection in dental plaque, stomach or both was not statistically significant.

The funnel plot [Figure 1] indicated that although some publication bias might have happened in this study, the effect is not too much and it is not statistically significant (P=0.256).

DISCUSSION

The results showed that the co-infection of dental plaque and gastric H. pylori is about 50%. Out of the 23 reviewed papers, 12 were inconsistent with this co-occurrence and 11 disagreed to this hypothesis. Difference in disease diagnostic indices in mouth, H. pylori diagnostic methods, H. pylori antibiotic treatments and criteria for selecting the patients are among the causes of inconsistency.

As shown in Table 1, a total of 23 studies reviewed have used seven different diagnostic methods to determine the presence of H. pylori. Among them, rapid urease test (RUT) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were the ones mostly used (in 10 and 13 studies, respectively). The researchers preferred RUT and PCR significantly because these methods have high level of accuracy. However, they are not unanimous concerning the priority of PCR over other methods. Some believe that since PCR is very sensitive, it can cause a series of pseudo-positive answers in some cases. In eight studies, microbial culture method was used as a gold standard to determine the presence of H. pylori. Since some types of this bacterium cannot be cultured, it was not used frequently in these studies. It seems that using different tests such as PCR or microbial culture is one of the serious factors involved in the lack of agreement between the results of different researchers. Finding a correlation between H. pylori diagnostic method and its occurrence in the dental plaque was also not possible because almost all of the researchers used more than two tests in each study.

In some studies like those of Gebara and Ozdemir, the method was different; in these studies, the patients were studied before and after the three-medicine treatment.[2,10] Carrying out these studies seems very applicable. In all reviewed studies, totally five three-medicine treatments were used with Omeprazol being similar in all five regimes and Clarithromycin and Amoxycilin being prescribed in three and four regimens, respectively.

In almost all studies, the criterion for entering the study was similar. Most studies examined the patients with dyspeptic symptoms referred to digestive specialty wards. These patients were supposed to undergo endoscopy of their upper digestive system. Only two studies, i.e. Kim and Guzik studies, did not mention the criterion for choosing the patients.[5,17]

The data from some relevant studies such as what has been reported in Song et al, cannot be pooled with other data due to the very different method used for H. pylori diagnosis and different inclusion criteria.[18]

Avcu has also divided the patients into three groups as good, moderate and poor concerning oral health. Thus, it was not easy to pool this subgroup analysis with the findings from other studies.[11]

One of the limitations of such a study was that dental plaque is not the only source of H. pylori and tongue dorsal and saliva of patients should also be taken into consideration. However, studies like those of Gebara and Guzik have examined the presence of H. pylori in saliva.[1,3] Since the present research shows a high agreement upon the simultaneous presence of H. pylori in dental plaque and stomach of patients, it can be concluded that these two conditions occur and come together; however, it does not mean that dental plaque can be a suitable place for H. pylori infection return.

Butt′s study was the only one to review the therapeutic effect of dental treatment on removing dental plaque to prevent gastric H. pylori re-infection.[12]

Although three of four Iranian researchers used the most reliable methods (PCR and culture), all of these four studies have shown that Hp could not play a role in the recurrence or incidence of dyspepsia in the studied patients, hence the results of Iranian studies support the hypothesis that Hp may belong to the normal microflora of the oral cavity.[9,21–23]

Results of this study suggest that periodontal treatment, removal of dental plaque and thus promotion of patients′ oral health can be used as a complementary method for the usual triple therapy for patients with H. pylori gastritis. But we still do not have enough evidence in this field, So, carrying out further interventional studies to prove that dental care after H. pylori eradication including bacterial plaque control procedures such as chlorhexidine irrigation and mechanical dental plaque removal is a critical step for preventing recurrence of H. pylori seems very essential. The serotype similarity between H. pylori in dental plaque and stomach should also be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was financially supported by Physiology Research center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Research No: 86/139). The authors wish to thank sincere cooperation of this center.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Physiology Research center of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (Research No: 86/139)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik E, Karczewska WB, Guzik TG, Kapera P, Targosz A, Konturek SJ, et al. Association of the presence of Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and in the stomach. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;55:105–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gebara EC, Faria CM, Pannuti C, Chehter L, Mayer MP, Lima LA. Persistence of Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity after systemic eradication therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:329–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebara EC, Pannuti C, Faria CM, Chehter L, Mayer MP, Lima LA. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori detected by polymerase chain reaction in the oral cavity of periodontitis patients. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:277–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2004.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kignel S, Almeida Pina F, Andre EA, Mayer MP, Birman EG. Occurrence of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva of dyspeptic patients. Oral Dis. 2005;11:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik E, Bielanski W, Guzik TG, Loster B, Konturek SJ. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and its implications for gastric infection, periodontal health, immunology and dyspepsia. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umeda M, Kobayashi H, Takeuchi Y, Hayashi J, Morotome-Hayashi Y, Yano K, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori detected by PCR in the oral cavities of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2003;74:129–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand PS, Nandakumar K, Shenoy KT. Are dental plaque, poor oral hygiene, and periodontal disease associated with Helicobacter pylori infection? J Periodontol. 2006;77:692–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berroteran A, Perrone M, Correnti M, Cavazza ME, Tombazzi C, Goncalvez R, et al. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in the oral cavity and gastroduodenal system of a Venezuelan population. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:764–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-9-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitsazi MT, Fattahi E, Farahani RM, Fattahi S. Helicobacter pylori in the dental plaque: is it of diagnostic value for gastric infection? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:325–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozdemir A, Mas MR, Sahin S, Saglamkaya U, Ateskan U. Detection of Helicobacter pylori colonization in dental plaques and tongue scrapings of patients with chronic gastritis. Quintessence Int. 2001;32:131–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avcu N, Avcu F, Beyan C, Ural AU, Kaptan K, Ozyurt M, et al. The relationship between gastric-oral Helicobacter pylori and oral hygiene in patients with vitamin B12-deficiency anemia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:166–9. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.113589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butt AK, Khan AA, Izhar M, Alam A, Shah SW, Shafqat F. Correlation of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and gastric mucosa of dyspeptic patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namiot DB, Namiot Z, Kemona A, Bucki R, Gotebiewska M. Oral health status and oral hygiene practices of patients with peptic ulcer and how these affect Helicobacter pylori eradication from the stomach. Helicobacter. 2007;12:63–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhury CR, Choudhury AD, Alam S, Markus AF, Tanaka A. Presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity of betel-quid (′Paan′) chewers with dyspepsia: Relationship with periodontal health. Public Health. 2003;117:346–7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young KA, Allaker RP, Hardie JM. Morphological analysis of Helicobacter pylori from gastric biopsies and dental plaque by scanning electron microscopy. Oral MicrobiolImmunol. 2001;16:178–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2001.016003178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teoman I, Ozmeric N, Ozcan G, Alaaddinoglu E, Dumlu S, Akyon Y, et al. Comparison of different methods to detect Helicobacter pylori in the dental plaque of dyspeptic patients. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11:201–5. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim N, Lim SH, Lee KH, You JY, Kim JM, Lee NR, et al. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva. Korean J Intern Med. 2000;15:187–94. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2000.15.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song O, Lange T, Spahr A, Adler G, Bode G. Characteristic distribution pattern of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva detected with nested PCR. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:349–53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-4-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Q, Haller B, Ulrich D, Wichelhaus A, Adler G, Bode G. Quantitation of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque samples by competitive polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:218–22. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin NC, Ho KY, Tsai CC, Wu DC, Jen CM, Wang WM. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque: A possible source of gastric re-infection. J Dent Res. 2003;82:154. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdolsamadi HR, Hooshmand B, Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Evaluation the existence of the Helicobacter pylori in stomach, subgingival plaque and samples taken from periodontal pockets in dyspeptic patients by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J Dent Mashhad Univ Med Sci. 2005;29:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasrolahei M, Maleki I, Fakheri H. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori colonization in dental plaque and gastric infection. MJIRC. 2004;7:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goudarzi H, Islami G, Pourmohammad A, Riazi M. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori colonization in the dental plaque and its colonization in the gastric mucosa. Shahid Beheshti Med Sci Univ J Dent School. 2000;1:54–9. [Google Scholar]