Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

The cholinergic agonist levamisole is widely used to treat parasitic nematode infestations. This anthelmintic drug paralyses worms by activating a class of levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptors (L-AChRs) expressed in nematode muscle cells. However, levamisole efficacy has been compromised by the emergence of drug-resistant parasites, especially in gastrointestinal nematodes such as Haemonchus contortus. We report here the first functional reconstitution and pharmacological characterization of H. contortus L-AChRs in a heterologous expression system.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

In the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, five AChR subunit and three ancillary protein genes are necessary in vivo and in vitro to synthesize L-AChRs. We have cloned the H. contortus orthologues of these genes and expressed them in Xenopus oocytes. We reconstituted two types of H. contortus L-AChRs with distinct pharmacologies by combining different receptor subunits.

KEY RESULTS

The Hco-ACR-8 subunit plays a pivotal role in selective sensitivity to levamisole. As observed with C. elegans L-AChRs, expression of H. contortus receptors requires the ancillary proteins Hco-RIC-3, Hco-UNC-50 and Hco-UNC-74. Using this experimental system, we demonstrated that a truncated Hco-UNC-63 L-AChR subunit, which was specifically detected in a levamisole-resistant H. contortus isolate, but not in levamisole-sensitive strains, hampers the normal function of L-AChRs, when co-expressed with its full-length counterpart.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

We provide the first functional evidence for a putative molecular mechanism involved in levamisole resistance in any parasitic nematode. This expression system will provide a means to analyse molecular polymorphisms associated with drug resistance at the electrophysiological level.

Keywords: recombinant receptor expression, acetylcholine receptor, nematode, levamisole, anthelminthic drug, drug resistance, Haemonchus contortus

Introduction

Gastrointestinal parasite infections are of major importance for human health and animal welfare. In the absence of effective vaccination strategies, control of parasitic helminths relies mainly on the use of broad spectrum anthelmintics such as levamisole, benzimidazoles (BZ) and avermectins (AVM). Intensive use of these drugs has inevitably led to the selection of resistant parasites. For example, the haematophagous parasite Haemonchus contortus (barber pole worm) is one of the most prevalent and pathogenic trichostrongylid species affecting small ruminants and threatening productivity and profitability in sheep and goat farming worldwide (Kaplan, 2004; Waller and Chandrawathani, 2005). H. contortus populations resistant to these three classes of anthelminthics and even combinations of drugs have been reported around the world (Kaplan, 2004). However, the rate of resistance selection for levamisole appears to be slower in H. contortus in comparison with BZ and AVM. Therefore, levamisole remains a useful tool to control BZ- and AVM-resistant parasites populations (Tyrrell and LeJambre, 2010).

Levamisole and other cholinergic agonists such as pyrantel and oxantel activate acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) expressed in nematode body-wall muscles (Aceves et al., 1970; Aubry et al., 1970; Harrow and Gration, 1985; Colquhoun et al., 1991; Martin et al., 2004). Exposure to these drugs causes spastic paralysis of the worms, which are either killed as with the free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans or expelled from the host organism in the case of H. contortus. The molecular composition of these levamisole-sensitive AChRs (L-AChRs) was first deciphered in C. elegans using the powerful genetic tools available in this model organism (Lewis et al., 1980; Lewis et al., 1987). Forward genetic screens for levamisole-resistant mutants in C. elegans identified the five genes encoding the five subunits of L-AChRs. They include three α-subunits (UNC-63, UNC-38 and LEV-8) and two non-α-subunits (UNC-29 and LEV-1) (Fleming et al., 1997; Culetto et al., 2004; Towers et al., 2005; Boulin et al., 2008). In addition, mutation of three additional genes, ric-3, unc-74 and unc-50, causes a complete loss of L-AChR expression in muscle cells. RIC-3 is a small transmembrane protein thought to act as a chaperone promoting AChR folding in the endoplasmic reticulum (Millar, 2008). It is involved in the assembly or maturation of at least four distinct AChRs in C. elegans, including L-AChRs and nicotine-sensitive AChRs (N-AChRs) in muscle (Halevi et al., 2002; 2003). The gene unc-74 encodes a thioredoxin closely related to the human TMX3 protein (Haugstetter et al., 2005) and this protein is likely to be required for the proper folding of L-AChR subunits, although its function has not been characterized in detail thus far. The gene unc-50 encodes a transmembrane protein mostly localized to the Golgi apparatus. In unc-50 mutants, L-AChRs, but no other ionotropic receptors, are targeted to lysosomes for degradation, suggesting a specific role for this protein in the regulation of L-AChR trafficking (Eimer et al., 2007). These three genes have been widely conserved through evolution from nematodes to humans.

In the absence of an efficient expression system for nematode L-AChRs, the biophysical and pharmacological characterization of these receptors has relied for almost four decades on in vivo electrophysiological analysis, conducted initially in Ascaris suum and Oesophagostomum dentatum (Robertson et al., 1999; Qian et al., 2006), and subsequently in C. elegans (Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Qian et al., 2008). Recently, we have obtained robust expression of C. elegans L-AChRs in Xenopus oocytes by providing cRNAs not only encoding the five L-AChR subunits, but also the three ancillary proteins RIC-3, UNC-50 and UNC-74 (Boulin et al., 2008). Interestingly, the sole expression of the A. suum orthologues of unc-29 and unc-38 in Xenopus oocytes was sufficient to reconstitute AChRs with varying sensitivity to levamisole and nicotine, depending on the relative expression levels of the two subunits (Williamson et al., 2009). Because A. suum is evolutionarily distant from C. elegans, these results suggested that the molecular composition of L- and N-AChRs could vary among nematodes, although the potential contribution of additional subunits in the formation of AChRs and the role of ancillary proteins for AChR expression was not explored in this study.

H. contortus and C. elegans belong to the same phylogenetic group (clade V), which also includes the human parasites Ancylostoma ceylanicum and Necator americanus (Mitreva et al., 2004). The precise molecular mechanisms involved in levamisole resistance are still poorly understood in trichostrongylid nematodes, but L-AChR subunit genes are obvious candidates based on results obtained in C. elegans. The orthologues of unc-29, unc-63, unc-38 and lev-1 have been cloned in H. contortus and other parasitic trichostrongylid species such as Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus colubriformis (Wiley et al., 1996; Hoekstra et al., 1997; Walker et al., 2001; Neveu et al., 2010). No clear orthologue of the C. elegans LEV-8 L-AChR subunit has been found (Williamson et al., 2007; Neveu et al., 2010), but a transcriptomic study carried out in H. contortus has recently identified another AChR subunit, Hco-ACR-8, as a candidate gene implicated in levamisole resistance (Fauvin et al., 2010). Hco-ACR-8 is most closely related to the C. elegans LEV-8 and ACR-8 receptor subunits. A comprehensive analysis performed on the laboratory-selected RHS6 levamisole-resistant isolate identified a truncated isoform of Hco-unc-63 (Hco-unc-63b), which was co-expressed with the full-length Hco-unc-63a transcript (Neveu et al., 2010). Truncated unc-63 transcripts were also identified in levamisole-resistant field isolates of the trichostrongylid species T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis, suggesting a possible link between variants of the unc-63 locus and levamisole resistance phenotypes (Neveu et al., 2010). However, this hypothesis could not be tested because of the lack of a heterologous expression system.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that two L-AChRs of H. contortus can be functionally reconstituted in Xenopus oocytes by co-expressing receptor subunits and conserved ancillary factors. We used this novel expression system to characterize these L-AChRs. Finally, we showed that a truncated AChR subunit found in levamisole-resistant isolates had a dominant-negative effect on the expression of wild-type H. contortus receptors in Xenopus oocytes. This result suggests a novel mechanism by which levamisole resistance can be obtained in trichostrongylid parasites. It further indicates the capability of this novel expression system to test the functional relevance of polymorphisms associated with resistance to levamisole in wild isolates.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures in this study were in strict accordance with guidelines of good animal practice defined by the Center France-Limousin ethical committee (France). Sheep studies were performed under experimental agreement 6623 approved by the Veterinary Services (Direction des Services vétérinaires) from Indre et Loire (France).

Accession numbers

The accession numbers for protein and cDNA sequences mentioned in this article are: C. elegans: ACR-2 NM_076727, ACR-3 NM_076728, ACR-8 – JF416644, ACR-12 NM_077861, LEV-1 NP_502534, LEV-8 NP_509932, RIC-3 NP_501299, UNC-29 NP_492399, UNC-38 NP_491472, UNC-50 NP_499279, UNC-63 NP_491533 and UNC-74 NP_491361; H. contortus: Hco-acr-8 EU006785, Hco-lev-1 GU060987, Hco-ric-3.1 HQ116823, Hco-ric-3.2 HQ116824, Hco-unc-29.1 GU060980, Hco-unc-38 GU060984, Hco-unc-50 HQ116822, Hco-unc-63a GU060985, Hco-unc-63b GU060986, Hco-unc-74 HQ116821; T. circumcincta: Tci-acr-8 HQ215517; T. colubriformis: Tco-acr-8 HQ215518.

Nematodes isolates

Experiments with H. contortus were performed on the levamisole-susceptible ISE (Roos et al., 2004) and the levamisole-resistant RHS6 isolates (Hoekstra et al., 1997). Adult nematodes (males and females) were collected 30 days after infection from the abomasal mucosa of sheep infected with 10 000 infective larvae (L3s). The T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis studies were carried out on the levamisole-susceptible TciSO and TcoSO isolates respectively (Neveu et al., 2010). For these species, sheep were experimentally infected with 5000 infective larvae (L3s) and adult nematodes (males) were collected from the abomasum (T. circumcincta) or the small intestine (T. colubriformis) 30 days after infection. The levamisole susceptibility or resistance status of all isolates used in this study has been confirmed previously (Neveu et al., 2010).

Molecular biology

Total RNA was prepared from 10 adult males from H. contortus ISE and RHS6 isolates, and from 50 adult males of T. circumcincta (TciSO) or T. colubriformis (TcoSO). Frozen worms were homogenized in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RNA pellets were dissolved in 25 µL of RNA secure resuspension solution (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and DNase-treated using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion). RNA concentrations were measured using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed on 3 µg of total RNA using the oligo (dT) RACER primer and superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Full-length cDNA sequences homologous to Cel-acr-8, Cel-ric-3, Cel-unc-50 and Cel-unc-74 were identified in H. contortus (ISE) using first-strand cDNA as a template. 3′ cDNA ends were identified by 3′ RACE PCR using the GeneRacer kit (Invitrogen) with primers based on partial genomic sequences available in the H. contortus genome sequence database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/blast/submitblast/h_contortus). The 5′ end of each cDNA was amplified by using the nematode spliced-leader sequence SL1 (ggtttaattacccaagtttgag). Amplification products were cloned in pGEMt-easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and fully sequenced. Full-length cDNA sequences homologous to Hco- and Cel-acr-8 were identified in T. circumcincta (TciSO) and T. colubriformis (TcoSO) using similar cloning strategies. 3′-RACE and SL1-PCR experiments were carried out using degenerate primers based on an alignment of H. contortus and C. elegans acr-8 cDNA sequences. The full length cDNAs coding for Hco-acr-8, Hco-lev-1, Hco-ric-3.1, Hco-ric-3.2, Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-38, Hco-unc-50, Hco-unc-63a and Hco-unc-74 were amplified by PCR using first-strand cDNA from the H. contortus ISE isolate, whereas Hco-unc-63b was amplified using cDNA from the RHS6 isolate. Next, amplification products were gel purified, and digested with XhoI and ApaI (HindIII and ApaI for Hco-unc-29.1), and cloned into the pTB207 expression vector (Boulin et al., 2008). Each construct was validated by sequencing. Finally, cRNA was synthetized in vitro from linearized plasmid DNA templates using the mMessage mMachine T7 transcription kit (Ambion). Lithium chloride-precipitated cRNA was resuspended in RNAse-free water and stored at −80°C. All primer sequences are reported in Supporting Information Tables S1 and S2.

Sequence analysis

Database searches were performed with the BLAST Network Service (NCBI), using the tBLASTn or BLASTX algorithms (Altschul et al., 1997). Signal peptide predictions were carried out using the the SignalP 3.0 server (Bendtsen et al., 2004) and membrane-spanning regions were predicted using TMpred. Coiled-coil motifs were predicted using the coiled-coil prediction program (http://www.russell.embl.de/cgi-bin/coils-svr.pl) and conserved protein domains were predicted using SMART (Schultz et al., 1998). Phylogenetic analyses were performed on full-length cDNA sequences as follows: the nucleotide sequences were first translated and amino acid sequences aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). The corresponding nucleotide alignment was obtained by concatenating codons using the REVTRANS server. The alignment was analysed using the pipelines available on the phylogeny.fr and the alignment refinement was performed using Gblocks (Castresana, 2000). The Maximum-likelihood (ML) tree was estimated using PhyML taking into account the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model (General Time Reversible) using the Datamonkey server. The statistical support of the inferred tree was evaluated by non-parametric bootstrap analysis with one thousand pseudoreplicates.

Electrophysiological studies in Xenopus laevis oocytes

Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared, injected, voltage-clamped and superfused as described previously (Paoletti et al., 1995), except that gentamycin was omitted from the conservation medium because prolonged treatments with this antibiotic can inhibit AChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Amici et al., 2005). For each oocyte, ∼36 nL of a cRNA injection mix containing 50 ng·µL−1 of each cRNA species were injected into the animal pole. Oocytes were recorded 2–3 days after injection. Unless otherwise noted, the standard external solution had the following composition (in mM): 100 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2 and 5 HEPES; pH 7.3 (NaOH). In some experiments (dose–response experiments, agonist and antagonist pharmacology) the calcium chelator BAPTA was loaded into oocytes to prevent activation of endogenous calcium-activated chloride conductances. BAPTA-AM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was diluted in Barth medium (100 µM final concentration), and oocytes were incubated for ∼4 h in 200 µL BAPTA-AM solution at 19°C. Data were collected and analysed using Clampex 9.2 and Clampfit 9.2 (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Data analysis

Results are shown as means ± SD. Data were fitted using KaleidaGraph 4.0 (Synergy Software). Dose–response curves were established as described previously (Boulin et al., 2008).

Materials

Acetylcholine chloride (ACh), BAPTA-AM, dihydro-β-erythroidine hydrobromide (DHβE), 1,1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium iodide (DMPP) (−)-tetramisole hydrochloride (levamisole) (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate, pyrantel citrate, (+)-tubocurarine chloride hydrate (dTC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Results

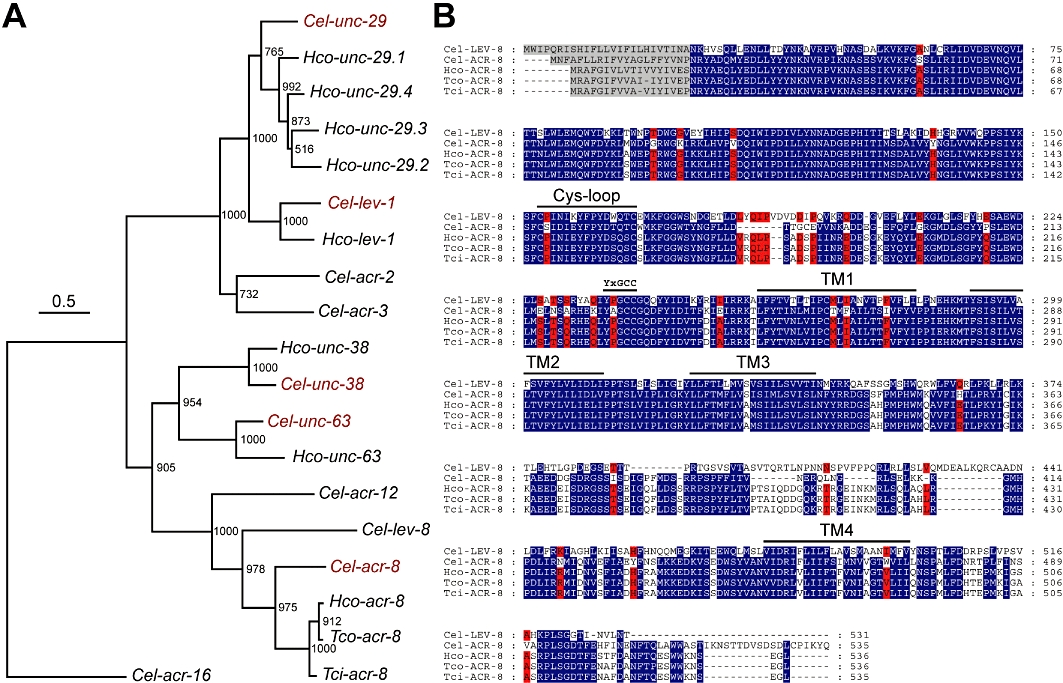

The trichostrongylid ACR-8 subunit might be distantly related to C. elegans LEV-8

Based on genetic, biochemical and electrophysiological data (Lewis et al., 1987; Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999; Gottschalk et al., 2005; Boulin et al., 2008), C. elegans L-AChR are composed of five receptor subunits (Cel-lev-1, Cel-lev-8, Cel-unc-29, Cel-unc-38 and Cel-unc-63). Clearly identifiable orthologues for four of these subunits have been found in the trichostrongylids H. contortus, T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis. Trichostrongylid L-AChR subunits are highly similar to their C. elegans counterparts, with a few notable differences. First, while C. elegans has only a single locus encoding a UNC-29 subunit, H. contortus has four paralogues named Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-29.2, Hco-unc-29.3 and Hco-unc-29.4 (Neveu et al., 2010). Of these four subunits, Hco-UNC-29.1 is the most similar to UNC-29 (79% identity, 88% amino-acid similarity). Second, no signal peptide is readily identifiable in any trichostrongylid LEV-1 subunit (Neveu et al., 2010). Third, no clear homologue of Cel-lev-8 has been found so far using bioinformatic or experimental approaches. The closest homolog of Cel-lev-8 in trichostrongylids is the AChR subunit ACR-8.

Using a PCR-based strategy, we have cloned the full-length acr-8 cDNA sequences from three levamisole-sensitive trichostrongylid nematodes (H. contortus ISE isolate, T. circumcincta TciSO isolate, T. colubriformis TcoSO isolate). The acr-8 orthologues identified in H. contortus, T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis, have been designated Hco-acr-8, Tci-acr-8 and Tco-acr-8, respectively, following recent nomenclature recommendations (Beech et al., 2010). The trichostrongylid ACR-8 sequences contain the typical features of an AChR subunit. All three subunits possess a YxxCC motif in loop C of the ACh-binding site, defining them as α subunits (Figure 1B). Even though trichostrongylid ACR-8 sequences are mostly similar to Cel-ACR-8 (percentage identities ranging from 68 to 69%), they also share common amino-acid signatures with the Cel-LEV-8 sequence, which are absent in Cel-ACR-8 (residues labelled in red in Figure 1B). Interestingly, these conserved amino-acids are mostly located between the cys-loop and the first transmembrane region, which corresponds to the agonist binding site region of AChR subunits. In C. elegans, UNC-29 can interact with the ACR-8 subunit in addition to the L-AChR subunits previously known to contribute to levamisole receptors (Gottschalk et al., 2005). Although acr-8 mutants are not resistant to levamisole, ACR-8 could replace another subunit in the C. elegans L-AChR (Almedom et al., 2009). Taken together, these results suggest that Hco-ACR-8 could be involved in the H. contortus L-AChR subunit composition in the absence of a trichostrongylid LEV-8 homologue.

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of L-AChR subunits in C. elegans and trichostrongylid nematodes. (A) Tree construction was performed on full-length cDNA sequences. Numbers at each node indicate bootstrap values corresponding to 1000 replicates. The scale bar represents nucleotide substitutions per site. The C. elegans acr-16 N-AChR subunit gene was used as an outgroup. The three letter prefixes in AChR subunit gene names Cel, Hco, Tci and Tco refer to C. elegans, H. contortus, T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis respectively. The five C. elegans AChR subunits required for the functional expression of the levamisole-sensitive AChR in Xenopus oocytes are labeled in red. (B) LEV-8 and ACR-8 sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm (Edgar, 2004) and further processed using GeneDoc. Predicted signal peptide sequences are shaded in grey. Amino acids conserved between Cel-LEV-8 and trichostrongylid ACR-8 sequences – but not C. elegans ACR-8 – are highlighted in red. The Cys-loop, the four transmembrane regions (TM1–TM4) and the primary agonist binding site are noted above the sequence.

Ancillary factors required for L-AChR expression in C. elegans are conserved in H. contortus

We previously demonstrated that three ancillary proteins encoded by ric-3, unc-50 and unc-74 are required for the robust expression of C. elegans L-AChRs in Xenopus oocytes (Boulin et al., 2008). We hypothesized that these ancillary proteins could also be necessary for heterologous expression of H. contortus L-AChRs.

After identifying likely candidates by performing BLAST searches on the H. contortus genome, we isolated the corresponding full-length cDNA sequences for Hco-unc-50, Hco-unc-74 and two ric-3 orthologues, Hco-ric-3.1 and Hco-ric-3.2. The H. contortus and C. elegans orthologues share typical sequence features (Table 1 and Supporting Information Figure S1). Hco-UNC-50 harbours a UNC-50 domain and five predicted transmembrane regions that are characteristic of Cel-UNC-50 (Eimer et al., 2007). Hco-UNC-74 contains a predicted signal peptide, a thioredoxin domain and a predicted transmembrane region in its C terminal part. The two H. contortus RIC-3 proteins have two transmembrane regions and C-terminal coiled-coil motifs. They only differ by seven amino-acid substitutions that do not affect transmembrane region and coiled-coil motif predictions. The corresponding genes mapped unambiguously to two distinct supercontigs (0006784 and 0043984) suggesting a recent duplication of the gene in H. contortus. Interestingly, partial coding sequences sharing significant similarity with each of the C. elegans and H. contortus ancillary factors can be easily identified in Brugia malayi and A. suum genomic databanks (Supporting Information Figure S1). This suggests that ancillary proteins are conserved among nematodes distantly related to C. elegans.

Table 1.

Comparison of H. contortus ancillary factors with their C. elegans orthologues

| Gene name | Accession number | Full-length cDNA size (bp) | Protein sequence length (aa) | C. elegans orthologue (e value) | % Amino acid identity / similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hco-ric-3.1 | HQ116823 | 1465 | 365 | Cel-RIC-3 (3e-54) | 56/70 |

| Hco-ric-3.2 | HQ116824 | 1468 | 365 | Cel-RIC-3 (5e-54) | 56/70 |

| Hco-unc-50 | HQ116822 | 1350 | 298 | Cel-UNC-50 (5e-112) | 73/84 |

| Hco-unc-74 | HQ116821 | 1574 | 445 | Cel-UNC-74 (2e-123) | 51/70 |

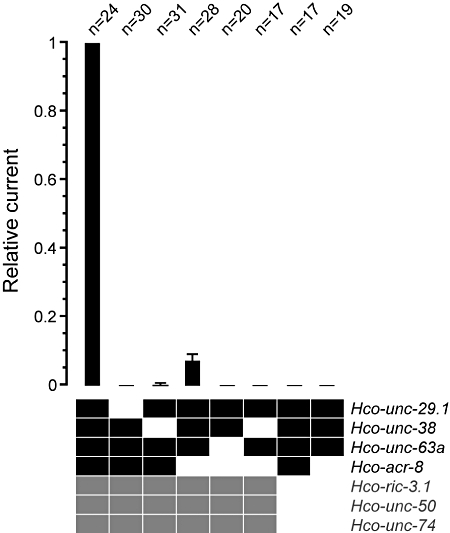

Reconstitution of H. contortus levamisole-sensitive AChRs in Xenopus laevis oocytes

Our strategy to express H. contortus L-AChRs was based on the previous reconstitution of C. elegans L-AChRs (Boulin et al., 2008; Jospin et al., 2009). We co-injected in vitro transcribed cRNAs of the four AChR subunits Hco-acr-8, Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-38 and Hco-unc-63a with cRNAs encoding three conserved ancillary factors Hco-ric-3.1, Hco-unc-50 and Hco-unc-74 (Figure 2). This combination of cRNAs led to the robust expression of levamisole-sensitive AChRs two to three days after injection. Application of 100 µM ACh or 100 µM levamisole elicited rapidly increasing currents in the µA range with little to no desensitization (Figure 3A). Addition of the Hco-lev-1 subunit did not result in any detectable change in expression, suggesting that this subunit is not required for the functional expression of the receptor (data not shown). This result is consistent with the absence of predicted signal peptides in any of the trichostrongylid lev-1 orthologues, suggesting that these subunits cannot be properly inserted in the membrane (Neveu et al., 2010). Hco-LEV-1 was therefore omitted from subsequent expression experiments.

Figure 2.

Four receptor subunits and three ancillary factors are required for efficient expression of Hco-L-AChR1. Co-injection of four receptor subunits (black squares) and three ancillary factors (grey squares) yields the strongest currents (average 540 nA (n = 24) with 500 µM ACh). Removal of the Hco-acr-8 subunit from the injection mix reduced average currents by 93 ± 1.6% (n = 28). No other combination yielded any measurable currents, except in very rare instances when Hco-unc-38 was removed. In particular, co-injection of four Hco-L-AChR1 subunits alone is not sufficient for expression, highlighting the crucial role of the three ancillary factors Hco-RIC-3.1, Hco-UNC-50 and Hco-UNC-74. Currents were measured once the steady state was reached. Numbers above bars indicate the number of oocytes recorded for each condition.

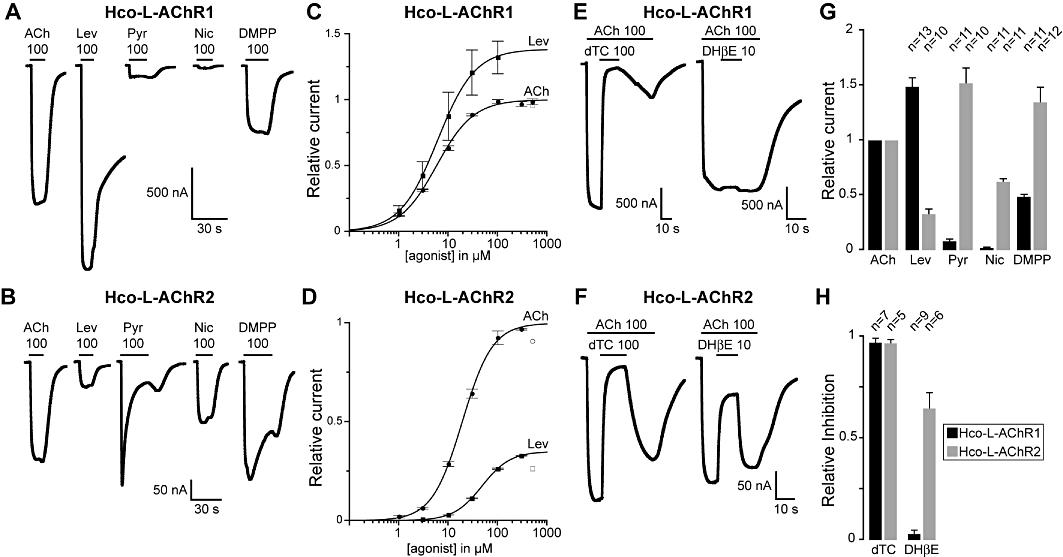

Figure 3.

Pharmacology of H. contortus levamisole-sensitive AChR. (A) Hco-L-AChR1 and (B) Hco-L-AChR2 were challenged with a series of cholinergic agonists (ACh, DMPP, Nic: nicotine) and anthelmintic agents (Lev: levamisole, Pyr: pyrantel). (C) and (D) ACh and levamisole dose–response curves for Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 respectively. The values indicated by open square and open circles were excluded from the fit. (E) and (F) Differential response of Hco-L-AChR to cholinergic antagonists. Currents elicited by 100 µM ACh can be efficiently blocked by 100 µM dTC in Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2. In contrast, the competitive antagonist DHβE only blocks ACh-induced currents in Hco-L-AChR2 but not in Hco-L-AChR1 consistently with the specific sensitivity of Hco-L-AChR2 to nicotine. (G) Relative efficacy of cholinergic agonists on Hco-L-AChR1 or Hco-L-AChR2. All values are normalized to the current elicited by application of 100 µM ACh. Numbers above bars indicate the number of oocytes recorded for each condition. (H) Relative efficacies of cholinergic antagonists on Hco-L-AChR1 or on Hco-L-AChR2. In (A) (B) (E) and (F) black horizontal bars indicate when agonists and antagonists are applied. All concentrations are indicated in µM. All oocytes were treated with 100 µM BAPTA-AM for 4 h prior to recording. All recordings were made with 1 mM external CaCl2.

To determine which receptor genes can be combined to produce functional receptors, we removed receptor subunits either individually or in combination. Removal of the Hco-acr-8 gene reduced expression by 93 ± 1.6% (Figure 2). Despite this strong reduction, expression was reliable and allowed the characterization of a second H. contortus receptor (Figure 3B). The combination of Hco-unc-29.1, −38, −63a and Hco-acr-8 resulting in the expression of the first potential H. contortus L-AChR will be henceforth referred to as Hco-L-AChR1, whereas the combination of Hco-unc-29.1, -38 and -63a will be referred to as Hco-L-AChR2. Hco-ACR-8 is an α-type AChR subunit and could theoretically assemble as a homopentamer, possibly explaining the observed difference between Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 injections. To test this hypothesis, we injected Hco-ACR-8 with the three ancillary factors. Although parallel expression of Hco-L-AChR1 was robust, we observed no currents for Hco-ACR-8 alone (n = 11), demonstrating that Hco-ACR-8 does not assemble into homopentamers in our experimental conditions. Therefore, Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 differ most likely by the inclusion of Hco-ACR-8 in Hco-L-AChR1. Next, we removed Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-38 or Hco-unc-63a from the Hco-L-AChR1 injection mix. In the case of Hco-unc-29.1 or Hco-unc-63a, no current was observed, indicating that these two subunits are essential elements of the Hco-L-AChR1 (Figures 2 and 4B). In the case of Hco-unc-38, we could find very rare instances where a few oocytes showed very small currents (250 times smaller than control currents on average). Because AChRs were obtained by the co-expression of the two AChR subunits Asu-UNC-29 and Asu-UNC-38 alone (Williamson et al., 2009), we co-injected Hco-unc-29.1 in combination with Hco-unc-38 or Hco-unc-63a (in addition to the three ancillary factors). These combinations never yielded any detectable current (Figure 2), indicating that results obtained in Ascaris are not transposable to H. contortus.

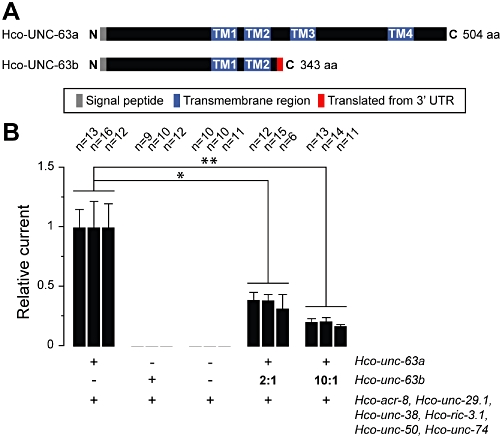

Figure 4.

Dominant-negative effect of a truncated form of Hco-UNC-63 on Hco-L-AChR1 currents. (A) Schematic representation of Hco-UNC-63a and Hco-UNC-63b. The Hco-UNC-63b truncated protein retains a signal peptide, the entire N-terminal extracellular domain, two transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2) and has an additional 26 C-terminal residues resulting from the translation of 3′ UTR sequences. (B) Expression of Hco-UNC-63b in the context of Hco-L-AChR1 decreases receptor expression by 36.5 ± 4.1% (2:1 ratio) and 19.5 ± 2.2% (10:1 ratio). Hco-UNC-63a is an essential component of Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-UNC-63b cannot substitute for wild-type Hco-UNC-63a to form functional receptors. ‘+’ and ‘−’ indicate when a component has been added or not. In each case Hco-acr-8, Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-38, Hco-ric-3.1, Hco-unc-50 and Hco-unc-74 were co-injected with either one or both Hco-unc-63 cRNA variants. ‘2:1’ and ‘10:1’ indicate the relative ratio of truncated to wild-type Hco-unc-63 used. Each wild-type cRNA was injected at 25 ng·µL−1 (vs. 50 ng·µL−1 in all other experiments). Average currents for Hco-L-AChR1 were 161 ± 144 nA. Currents were recorded two days after injection.

Finally, we investigated the requirement for Hco-ric-3.1, Hco-unc-50 and Hco-unc-74. Injection of the Hco-L-AChR1 or Hco-L-AChR2 receptor subunits without the three ancillary factors never yielded any detectable currents (Figure 2). This clearly demonstrates the strict requirement of these factors for expression of H. contortus L-AChR in Xenopus oocytes, as it was previously reported for C. elegans L-AChRs (Boulin et al., 2008).

Pharmacology of H. contortus L-AChRs

Pharmacological profiles of Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 were established using cholinergic agonists (ACh, nicotine and DMPP) and anthelminthic agents (levamisole and pyrantel). Both receptors have strikingly different pharmacological profiles. Although Hco-L-AChR1 strongly responds to levamisole (148.8 ± 7.6% of ACh response), Hco-L-AChR2 response was much weaker (32.7 ± 4.2% of ACh response) (Figure 3). In contrast, pyrantel responses were larger in Hco-L-AChR2 (152.1 ± 13.3%) than Hco-L-AChR1 (8.1 ± 1.4%). DMPP activated both receptors (Hco-L-AChR1: 48.5 ± 1.7%; Hco-L-AChR2: 134.6 ± 13.4%). But similarly to pyrantel, response to DMPP differed qualitatively in Hco-L-AChR2. While continuous application of pyrantel and DMPP on Hco-L-AChR1 yielded a rapidly activating response that quickly reached a plateau value (Figure 3A), continuous application of pyrantel and DMPP on Hco-L-AChR2 resulted in a rapidly decaying response (Figure 3B). In addition, a post-wash rebound could be seen in Hco-L-AChR2, but not in Hco-L-AChR1. These differences could be due to reversible channel block by pyrantel and DMPP. Alternatively, pyrantel and DMPP could promote the desensitized state of Hco-L-AChR2. Finally, although Hco-L-AChR1 failed to respond significantly to nicotine (2.0 ± 0.3%), Hco-L-AChR2 responded robustly to nicotine application (62.2 ± 2.5%), suggesting that at least one nicotine-binding site is created when only the three receptor subunits Hco-unc-29.1, Hco-unc-38 and Hco-unc-63a are co-expressed.

Next, we compared the relative sensitivities of Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 with ACh and levamisole by establishing full dose–response curves (Figure 3C and D). We find that Hco-L-AChR1 has a significantly higher affinity for acetylcholine and levamisole than Hco-L-AChR2. EC50 for acetylcholine was 5.8 ± 0.5 µM (n = 5) for Hco-L-AChR1 compared with 19.2 ± 0.7 µM (n = 7) for Hco-L-AChR2. EC50 for levamisole was 6.08 ± 0.3 µM (n = 5) for Hco-L-AChR1 compared with 48.4 ± 0.9 µM (n = 4) for Hco-L-AChR2. In contrast, cooperativity was more pronounced in the case of Hco-L-AChR2 as measured by the increase in Hill coefficient values (Hco-L-AChR1: ACh nH = 1.16 ± 0.08 and Lev nH = 1.15 ± 0.04; Hco-L-AChR2: ACh nH = 1.42 ± 0.06 and Lev nH: 1.52 ± 0.03).

These results demonstrate that two H. contortus L-AChRs with very different pharmacology can be assembled in Xenopus oocytes depending on the set of receptor subunits that are provided. Given that no in vivo data is available in H. contortus regarding the spatial and temporal expression patterns of these receptor subunits, it is not possible at this stage to state whether both of these receptors are expressed in vivo and whether they could correspond to the multiple types of L-AChRs that have been described in the muscles of other parasitic nematodes (Robertson et al., 1999).

The competitive antagonist DHβE blocks nicotine-sensitive Hco-L-AChR2 but not nicotine-insensitive Hco-L-AChR1

In the presence of 100 µM ACh, both Hco-L-AChR1 and Hco-L-AChR2 are efficiently blocked by the application of 100 µM of the canonical cholinergic antagonist d-tubocurarine (dTC) (97.0 ± 1.9% and 96.6 ± 1.7%, respectively) (Figure 3E, F and H). However, the two receptors respond very differently to the competitive nicotinic antagonist dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE). Consistent with their differential response to nicotine, DHβE blocked ACh-activated currents in the nicotine-sensitive Hco-L-AChR2 very efficiently, but did not antagonize ACh-evoked currents in the nicotine-insensitive Hco-L-AChR1 (64.7 ± 7.6% and 2.9 ± 1.7%, respectively). This further suggests that a typical nicotine binding site must be formed in H. contortus L-AChR when Hco-acr-8 is absent. This pharmacology is also comparable to that observed in C. elegans where L-AChRs are not activated by nicotine and are insensitive to DHβE, while N-AChRs are activated by nicotine and blocked by DHβE, both in vivo (Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999) and in vitro (Boulin et al., 2008).

A truncated form of Hco-UNC-63 antagonizes H. contortus L-AChR expression in Xenopus oocytes

The molecular mechanisms and the genes involved in levamisole resistance are still largely unknown in parasitic nematodes. The unc-63 locus has emerged as a possible candidate as transcripts corresponding to truncated forms of unc-63 mRNAs (unc-63b) were specifically identified in levamisole-resistant isolates of three trichostrongylid species (H. contortus, T. circumcincta and T. colubriformis) (Neveu et al., 2010). Intriguingly, these isolates also expressed full-length unc-63 transcripts (unc-63a) in addition to the truncated mRNAs. The truncated Hco-unc-63b transcript identified in the H. contortus RHS6 isolate encodes a predicted protein of 343 amino acids including a signal peptide, the entire N-terminal extracellular domain, two transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2) and 26 residues resulting from translation of the 3′ UTR (Neveu et al., 2010) (Figure 4A). Because co-expression of mammalian AChR subunits truncated after the M2 domain with wild-type subunits resulted in a decrease of surface receptors and associated receptor currents (Verrall and Hall, 1992; Sumikawa and Nishizaki, 1994), the truncated Hco-UNC-63b form might act as a dominant-negative on L-AChR expression.

To test this hypothesis, we injected increasing amounts of Hco-unc-63b cRNA with a fixed amount of wild-type L-AChR subunit cRNAs (Figure 4B). In agreement with the dominant-negative hypothesis, we observed a dose-dependent effect of Hco-UNC-63b on L-AChR currents. Injection of Hco-unc-63b RNA and Hco-L-AChR1 RNAs at a 2:1 ratio led to a reduction in average current down to 36.5 ± 4.1% of control (average of three independent experiments). When Hco-unc-63b RNA was injected at a 10:1 ratio, average current further decreased to 19.5 ± 2.2% of control (Figure 4B). This significant reduction in expression was not likely to be due to the saturation of the expression machinery as the total amount of injected RNA in the 10:1 ratio experiment was equivalent to the amount of cRNA injected to express Hco-L-AChR1 in other experiments. We also verified that Hco-UNC-63b does not allow the formation of a functional receptor when Hco-unc-63a is omitted.

Taken together, these results suggest that co-expression of the truncated Hco-unc-63b form with wild-type Hco-unc-63 subunits could inhibit the expression levels of the H. contortus L-AChR, and therefore could induce a levamisole-resistance phenotype in parasites expressing this mutant form.

Discussion and conclusion

We demonstrate here that two distinct H. contortus L-AChRs can be functionally reconstituted in Xenopus oocytes by providing different sets of receptor subunits. In addition, robust expression requires the presence of three conserved ancillary factors, as reported in the non-parasitic nematode C. elegans (Boulin et al., 2008). This experimental system provides a unique means to describe the pharmacological and biophysical properties of H. contortus L-AChRs and to analyse the functional impact of sequence polymorphisms detected in levamisole-resistant nematodes.

Functional conservation of L-AChRs between C. elegans and H. contortus

One of the striking features of C. elegans is the number of AChR subunits encoded in the genome, at least 29 (Jones et al., 2007), as compared with 17 in vertebrates. Despite its small number of neurons, C. elegans is the species potentially expressing the most diverse repertoire of AChRs. Genomic studies suggest that many of these subunits are absent in parasitic nematodes including B. malayi and A. suum (Williamson et al., 2007). Specifically, the lev-1 and lev-8 subunits, which are essential for L-AChR expression in C. elegans, were not found in these parasites, and L- and N-AChRs of these parasites can be reconstituted by expressing only different ratios of unc-29 and unc-38 without the need of accessory proteins (Williamson et al., 2009). Such discrepancies might have reflected divergence caused by different life styles between parasitic and free-living nematodes. Our current results rather suggest that it reflects the phylogenetic distance between C. elegans (clade V) and B. malayi and A. suum (clade III), as robust expression of L-AChRs from H. contortus (clade V) requires four different AChR subunits and three ancillary proteins, as we observed previously in C. elegans.

Interestingly, trichostrongylid orthologues of lev-1 were readily identified but a sequence coding for a signal peptide could never be identified by inspection of genomic sequences or in cloned mRNAs. Consistently, injection of the Hco-lev-1 cRNA did not change Hco-L-AChR1 expression and levamisole sensitivity, suggesting that it was indeed not incorporated into the receptor. The absence of deleterious variation in the coding sequence suggests, however, that lev-1 remained under positive selection pressure. Whether complex genetic processing of the mRNA, such as trans-splicing between two mRNAs (Fischer et al., 2008), occurs at specific developmental stages or in some specific cells to introduce a signal peptide into Hco-LEV-1 cannot be ruled out.

lev-8 could not be found in H. contortus, but functional L-AChR reconstitution indicates that ACR-8, the closest homologue of LEV-8 in C. elegans, is assembled in the receptor and plays a pivotal role in drug sensitivity. Two points might be meaningful. First, biochemical data in C. elegans suggest that ACR-8 might associate with other subunits found in muscle L-AChR (Gottschalk et al., 2005). Second, the similarity between Hco- and Cel-ACR-8 is widely spread over the length of the primary amino-acid sequence, except for some motifs which are LEV-8 signatures in C. elegans (Figure 1B). Most notably, the principal ligand site defined by a YxxCC motif is identical for trichostrongylid ACR-8 and C. elegans LEV-8 (YPGCC vs. YAGCC for Cel-ACR-8). It is tempting to hypothesize that the conservation of these particular residues could be associated with their specific agonist-binding properties. It raises the possibility that lev-8 and acr-8 arose from a duplication that occurred after the divergence between strongyloidea and rhabditoidea.

Ancillary factors encoded by ric-3, unc-50 and unc-74 homologues are required for the expression of H. contortus L-AChRs in Xenopus oocytes, as previously reported for C. elegans L-AChRs (Boulin et al., 2008). Although orthologues of these three genes are present in the Xenopus genome, they cannot functionally replace their C. elegans or H. contortus counterparts. They could be expressed at insufficient levels in unfertilized oocytes, or their sequence might have diverged enough that they can not functionally replace their nematode counterparts. Recent work suggests that it is not the case for all parasitic levamisole receptors. A. suum UNC-29 and UNC-38 can assemble into functional levamisole- and pyrantel-sensitive receptors in Xenopus oocytes in the absence of additional A. suum factors (Williamson et al., 2009). However, this required the use of significantly greater amounts of receptor subunit RNA (25 ng of each subunit instead of 1.8 ng in this study) suggesting less efficient assembly or trafficking of the receptor, even though we cannot exclude the possibility that observed differences could reflect specific properties of L-AChRs. A bioinformatic analysis of available genome and EST data from A. suum clearly identified partial sequences homologous to the three ancillary factors (Supporting Figure S1). Whether these factors could be used to enhance the efficiency of A. suum L-AChR expression remains to be investigated.

Diversity of levamisole-sensitive receptors in nematodes

L-AChRs have been studied at the single channel level in C. elegans, A. suum and O. dentatum. These studies have highlighted some major differences between C. elegans and parasitic nematode L-AChR. For instance, three and four conductances ranging from 18 to 53 pS have been described for levamisole-activated channels in A. suum and O. dentatum, respectively (Robertson et al., 1999; Qian et al., 2006), while only one conductance level (around 30 pS) was found in the C. elegans muscle (Rayes et al., 2007; Qian et al., 2008). Consistently, genetic evidence suggests that only a single L-AChR is expressed in C. elegans muscle (Richmond and Jorgensen, 1999). In addition, C. elegans muscle cells express a second class of AChRs, the N-AChR, with strikingly different biophysical and pharmacological properties. N-AChRs desensitize extremely rapidly upon prolonged exposure to agonists. They are activated by nicotine, blocked by DHβE and insensitive to levamisole. These differences are explained by the molecular composition of N-AChRs, which are homomers of the ACR-16 subunit, a subunit closely related to the α7 subunit in mammals. By contrast, the origin of the diversity of parasitic AChRs is not understood at the genetic level.

Different levamisole-sensitive receptors could either contain different receptor subunits or the same subunits could be combined with different stoichiometries. In vitro experiments with A. suum levamisole receptors have suggested that different subunit stoichiometries could explain differences in pharmacology (Williamson et al., 2009). We show here for H. contortus that two L-AChRs with very different pharmacological properties can be formed when the Hco-ACR-8 receptor subunit is present or absent. Strikingly, Hco-L-AChR1, which contain Hco-ACR-8, are very sensitive to levamisole, weakly responsive to pyrantel, and insensitive to nicotine and DHβE. Hco-L-AChR2, in which ACR-8 was removed, are less responsive to levamisole, more sensitive to pyrantel and respond to nicotine and DHβE. Injecting Hco-ACR-8 with only two other receptor subunits never yielded any currents. We could therefore conclude that Hco-ACR-8 does not entirely replace another receptor subunit but rather that it must be included in the receptor in exchange for one or two other subunits. Indeed, the Hco-L-AChR2 receptor is formed when only Hco-UNC-29.1, Hco-UNC-38 and Hco-UNC-63a are co-injected. This allows for only two stoichiometries since each subunit is essential: either 3:1:1 or 2:2:1. When Hco-ACR-8 is added to form Hco-L-AChR1, the new subunit composition must be either (Hco-ACR-8)1: 2:1:1 or (Hco-ACR-8)2: 1:1:1. Therefore, inclusion of Hco-ACR-8 will modify both the receptor's subunit composition and stoichiometry.

Our oocyte expression system allows for the first time to explore the possible subunit compositions of H. contortus AChRs. Ideally, single channel experiments would be required to determine which receptor subtypes correspond to conductances in vivo, potentially mirroring the three and four subtypes identified in A. suum and O. dentatum respectively. In addition, multiple paralogues exist for some of the subunits and it remains possible that specific combinations account for the diversity of conductances observed in parasitic nematode. However, definitive assignment of specific subunit combinations to an in vivo conductance would require genetic experiments, which are not yet feasible in these parasitic nematodes.

Mechanisms of levamisole resistance in trichostrongylid nematodes

In addition to the pharmacological characterization of H. contortus L-AChRs, we propose here the first mechanistic model explaining levamisole-resistance in certain isolates of trichostrongylid parasites. We had recently reported that truncated forms of the L-AChR subunit UNC-63 are co-expressed with their full-length counterparts in levamisole-resistant isolates of three trichostrongylid nematodes (H. contortus RHS6, T. circumcincta TciNZ and T. colubriformis TcoGA) (Neveu et al., 2010). We hypothesized that truncated receptor subunits could have a dominant-negative effect on L-AChR function by competing with wild-type subunits during receptor assembly. This hypothesis was consistent with previous data obtained in mammalian muscle AChR where co-expression of truncated and full-length receptor subunits resulted in the alteration of receptor function or expression (Verrall and Hall, 1992; Sumikawa and Nishizaki, 1994). We demonstrate that when co-expressed with Hco-L-AChR1 receptors in Xenopus oocytes, the truncated Hco-UNC-63b subunit has a strong dose-dependent dominant-negative effect on receptor expression.

Such a resistance mechanism, involving the down-regulation rather than complete loss of L-AChR expression might be more compatible with the parasitic lifestyle of H. contortus. Indeed, complete loss of L-AChRs in C. elegans null mutants of the unc-63 receptor subunit is accompanied by a strong uncoordinated movement phenotype. Because parasites are required to move efficiently to remain infective, the complete loss of L-AChRs might represent a strong selective disadvantage. Accordingly, levamisole-binding experiments performed on wild-type and levamisole-resistant isolates identified changes in the binding characteristics or in the expression level of L-AChR rather than the absence of L-AChRs (Sangster et al., 1988; 1998; Moreno-Guzman et al., 1998). More generally, levamisole-resistant parasites may be less well coordinated than wild-type nematodes, and this loss of general fitness may make selection for levamisole resistance slower to develop and less stable than other types of anthelminthic resistance, in the absence of continuing anthelmintic selection pressure. In the future, our oocyte expression system will provide a means to test the functional relevance of polymorphisms linked to levamisole resistance and to characterize the sensitivity of wild-type and mutated receptors to known and forthcoming anthelminthic compounds.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Laetitia Mony, Morgane Riou, David Stroebel, Shixin Ye and Shujia Zhu for reagents, and Pierre Paoletti for feedback and helpful comments. We also thank Alexandra Blanchard-Letort for help with phylogenetic analyses. The H. contortus ISE and RHS6 isolates were kindly provided by Franck Jackson and Fred Boorgsteed respectively. Aymeric Fauvin is a grateful recipient of a PhD grant from ‘Région Centre’ and Animal Health Division of INRA. This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and by a grant from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale ‘Equipe FRM’.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AVM

avermectins

- BZ

benzimidazoles

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- DMPP

1,1-dimethyl-4-phenylpiperazinium

- dTC

(+)-tubocurarine

- Hco-L-AChR1

H. contortus-levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor 1

- Hco-L-AChR2

H. contortus-levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor 2

- L-AChR

levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor

- N-AChR

nicotine-sensitive acetylcholine receptor

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 Conservation of RIC-3, UNC-50 and UNC-74 ancillary factors in Ascaris suum, Brugia malayi, Caenorhabditis elegans and Haemonchus contortus. Protein alignments were constructed using the MUSCLE algorithm and were further processed using GeneDoc. Consensus regions are shaded in blue. (A) RIC-3 homologues. The seven amino acids which differ between Hco-RIC-3.1 and Hco-RIC-3.2 are labeled in cyan. Domain annotations correspond to C. elegans RIC-3. The two transmembrane domains and the three coiled-coil domains are noted above the sequence. The Brugia malayi alignment is based on two partial sequences: kb29b08.y1 and XP_001898706.1. The names of the partial RIC-3 sequences from A. suum are indicated below the sequence. (B) UNC-50 homologues. Domain annotations correspond to C. elegans UNC-50. The five transmembrane domains are noted above the sequence. The Brugia malayi alignement is based on XP_1895364.1. The names of the partial sequences from A. suum used for the alignment are indicated below the sequence. (C) UNC-74 homologues. Domain annotations correspond to C. elegans UNC-74. The C-terminal transmembrane domain and the thioredoxin domain are noted above the sequence. The Brugia malayi alignement is based on XP_001901171.1. ED247067 was the only partial sequences from A. suum retrieved during our bioinformatic analysis.

Table S1 Primer sequences used for 3′ RACE and SL1-PCR experiments

Table S2 Primers used for cDNA amplification and cloning

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Aceves J, Erlij D, Martinez-Maranon R. The mechanism of the paralysing action of tetramisole on Ascaris somatic muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1970;38:602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb10601.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almedom RB, Liewald JF, Hernando G, Schultheis C, Rayes D, Pan J, et al. An ER-resident membrane protein complex regulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit composition at the synapse. EMBO J. 2009;28:2636–2649. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici M, Eusebi F, Miledi R. Effects of the antibiotic gentamicin on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:627–637. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry ML, Cowell P, Davey MJ, Shevde S. Aspects of the pharmacology of a new anthelmintic: pyrantel. Br J Pharmacol. 1970;38:332–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1970.tb08521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech RN, Wolstenholme AJ, Neveu C, Dent JA. Nematode parasite genes: what's in a name? Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulin T, Gielen M, Richmond JE, Williams DC, Paoletti P, Bessereau JL. Eight genes are required for functional reconstitution of the Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole-sensitive acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18590–18595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806933105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun L, Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. The pharmacology of cholinoceptors on the somatic muscle cells of the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum. J Exp Biol. 1991;158:509–530. doi: 10.1242/jeb.158.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culetto E, Baylis HA, Richmond JE, Jones AK, Fleming JT, Squire MD, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans unc-63 gene encodes a levamisole-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42476–42483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer S, Gottschalk A, Hengartner M, Horvitz HR, Richmond J, Schafer WR, et al. Regulation of nicotinic receptor trafficking by the transmembrane Golgi protein UNC-50. EMBO J. 2007;26:4313–4323. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauvin A, Charvet C, Issouf M, Cortet J, Cabaret J, Neveu C. cDNA-AFLP analysis in levamisole-resistant Haemonchus contortus reveals alternative splicing in a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;170:105–107. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SE, Butler MD, Pan Q, Ruvkun G. Trans-splicing in C. elegans generates the negative RNAi regulator ERI-6/7. Nature. 2008;455:491–496. doi: 10.1038/nature07274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JT, Squire MD, Barnes TM, Tornoe C, Matsuda K, Ahnn J, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans levamisole resistance genes lev-1, unc-29, and unc-38 encode functional nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5843–5857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05843.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk A, Almedom RB, Schedletzky T, Anderson SD, Yates JR, 3rd, Schafer WR. Identification and characterization of novel nicotinic receptor-associated proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 2005;24:2566–2578. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi S, McKay J, Palfreyman M, Yassin L, Eshel M, Jorgensen E, et al. The C. elegans ric-3 gene is required for maturation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:1012–1020. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevi S, Yassin L, Eshel M, Sala F, Sala S, Criado M, et al. Conservation within the RIC-3 gene family. Effectors of mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34411–34417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow ID, Gration AF. Mode of action of the anthelmintics morantel, pyrantel and levamisole on muscle cell membrane of the nematode Ascaris suum. Pestic Sci. 1985;16:662–672. [Google Scholar]

- Haugstetter J, Blicher T, Ellgaard L. Identification and characterization of a novel thioredoxin-related transmembrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8371–8380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra R, Visser A, Wiley LJ, Weiss AS, Sangster NC, Roos MH. Characterization of an acetylcholine receptor gene of Haemonchus contortus in relation to levamisole resistance. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;84:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AK, Davis P, Hodgkin J, Sattelle DB. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene family of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: an update on nomenclature. Invert Neurosci. 2007;7:129–131. doi: 10.1007/s10158-007-0049-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jospin M, Qi YB, Stawicki TM, Boulin T, Schuske KR, Horvitz HR, et al. A neuronal acetylcholine receptor regulates the balance of muscle excitation and inhibition in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RM. Drug resistance in nematodes of veterinary importance: a status report. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Wu CH, Berg H, Levine JH. The genetics of levamisole resistance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1980;95:905–928. doi: 10.1093/genetics/95.4.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JA, Elmer JS, Skimming J, McLafferty S, Fleming J, McGee T. Cholinergic receptor mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3059–3071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03059.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RJ, Clark CL, Trailovic SM, Robertson AP. Oxantel is an N-type (methyridine and nicotine) agonist not an L-type (levamisole and pyrantel) agonist: classification of cholinergic anthelmintics in Ascaris. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NS. RIC-3: a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor chaperone. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S177–S183. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitreva M, McCarter JP, Martin J, Dante M, Wylie T, Chiapelli B, et al. Comparative genomics of gene expression in the parasitic and free-living nematodes Strongyloides stercoralis and Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2004;14:209–220. doi: 10.1101/gr.1524804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Guzman MJ, Coles GC, Jimenez-Gonzalez A, Criado-Fornelio A, Ros-Moreno RM, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F. Levamisole binding sites in Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:413–418. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveu C, Charvet CL, Fauvin A, Cortet J, Beech RN, Cabaret J. Genetic diversity of levamisole receptor subunits in parasitic nematode species and abbreviated transcripts associated with resistance. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:414–425. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328338ac8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Neyton J, Ascher P. Glycine-independent and subunit-specific potentiation of NMDA responses by extracellular Mg2+ Neuron. 1995;15:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Martin RJ, Robertson AP. Pharmacology of N-, L-, and B-subtypes of nematode nAChR resolved at the single-channel level in Ascaris suum. FASEB J. 2006;20:2606–2608. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6264fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Robertson AP, Powell-Coffman JA, Martin RJ. Levamisole resistance resolved at the single-channel level in Caenorhabditis elegans. FASEB J. 2008;22:3247–3254. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayes D, Flamini M, Hernando G, Bouzat C. Activation of single nicotinic receptor channels from Caenorhabditis elegans muscle. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:1407–1415. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Jorgensen EM. One GABA and two acetylcholine receptors function at the C. elegans neuromuscular junction. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:791–797. doi: 10.1038/12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson AP, Bjorn HE, Martin RJ. Resistance to levamisole resolved at the single-channel level. FASEB J. 1999;13:749–760. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos MH, Otsen M, Hoekstra R, Veenstra JG, Lenstra JA. Genetic analysis of inbreeding of two strains of the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster NC, Riley FL, Collins GH. Investigation of the mechanism of levamisole resistance trichostrongylid nematodes of sheep. Int J Parasitol. 1988;18:813–818. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangster NC, Riley FL, Wiley LJ. Binding of [3H]m-aminolevamisole to receptors in levamisole-susceptible and -resistant Haemonchus contortus. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:707–717. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J, Milpetz F, Bork P, Ponting CP. SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5857–5864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumikawa K, Nishizaki T. The amino acid residues 1-128 in the alpha subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor contain assembly signals. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:257–264. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towers PR, Edwards B, Richmond JE, Sattelle DB. The Caenorhabditis elegans lev-8 gene encodes a novel type of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell KL, LeJambre LF. Overcoming macrocyclic lactone resistance in Haemonchus contortus with pulse dosing of levamisole. Vet Parasitol. 2010;168:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrall S, Hall ZW. The N-terminal domains of acetylcholine receptor subunits contain recognition signals for the initial steps of receptor assembly. Cell. 1992;68:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90203-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Hoekstra R, Roos MH, Wiley LJ, Weiss AS, Sangster NC, et al. Cloning and structural analysis of partial acetylcholine receptor subunit genes from the parasitic nematode Teladorsagia circumcincta. Vet Parasitol. 2001;97:329–335. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(01)00416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller PJ, Chandrawathani P. Haemonchus contortus: parasite problem no. 1 from tropics – Polar Circle. Problems and prospects for control based on epidemiology. Trop Biomed. 2005;22:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley LJ, Weiss AS, Sangster NC, Li Q. Cloning and sequence analysis of the candidate nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha subunit gene tar-1 from Trichostrongylus colubriformis. Gene. 1996;182:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson SM, Walsh TK, Wolstenholme AJ. The cys-loop ligand-gated ion channel gene family of Brugia malayi and Trichinella spiralis: a comparison with Caenorhabditis elegans. Invert Neurosci. 2007;7:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s10158-007-0056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson SM, Robertson AP, Brown L, Williams T, Woods DJ, Martin RJ, et al. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptors of the parasitic nematode Ascaris suum: formation of two distinct drug targets by varying the relative expression levels of two subunits. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000517. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.