Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

The satisfaction of the family is essential to the success of home care support services. This study aimed to assess home caregivers’ satisfaction with support services and to identify potential factors affecting their satisfaction.

DESIGN AND SETTINGS:

The study was conducted in the Family and Community Medicine Department at Riyadh Military Hospital using cross-sectional design over a period of six months.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

Two hundred forty participants were recruited by systematic random sampling from the division registry. Data were collected through telephone calls using a designed structured interview form. All research ethics principles were followed.

RESULTS:

The response rate was 76.25%. Most caregivers were patients’ sons or daughters. The duration of patients’ disabling illnesses varied from less than 1 year to up to 40 years. The majority of caregivers agreed that a home care services team provided the proper healthcare-related support to the patients and improved caregivers’ self-confidence in caring for their patients. Overall, on a scale of 100%, the median level of satisfaction was 90%, and 73.2% of caregivers had a satisfaction score of 75% or higher. Increased age, female gender, and more frequent home visits were positive independent factors associated with caregivers’ satisfaction scores.

CONCLUSION:

Although most caregivers are satisfied with the services provided by a home care support program, there are still areas of deficiency, particularly in physiotherapy, vocational therapy, and social services. The implications are that caregivers need to be educated and trained in caring for their patients and need to gain self-confidence in their skills. The program's administration should improve physiotherapy, vocational therapy, social services, and procedures for hospital referral.

Worldwide, the availability of home support services has grown considerably, as a result of longer life spans and advances in technology.1 One example of new technology is home tele-health, a technology that supports long-distance clinical health care.2 Various models have been constructed for efficient medical home support services. These models are designed to mainly identify and integrate the needs of patients and their family members.3 Understanding these various needs enhances the quality of work done and guarantees continuing improvement.4 Other models are based on nurse-led case management, which streamlines access to health care services and resources, thus decreasing caregiver burden and increasing satisfaction.1

The shift of care from hospitals and hospices to home can benefit patients and their family caregivers.5 Family caregivers perceive this shift as helpful to them.6 Costwise, Magnusson and Hanson7 found that all the cases that they studied achieved cost savings, with considerable benefits to all parties. Similarly, Dahi8 reported reductions in costs related to visits to specialty clinics and emergency rooms of 68% and 73%, respectively, among patients under home health care in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. However, for home care to be beneficial, the safety and comfort of patients and caregivers must be guaranteed,9 and the diversity of the caregivers should be taken into account.10

Support for family caregivers is crucial; otherwise, home care responsibilities add to family suffering.11 It is also crucial that the home care support services that are provided respond to family caregivers‘ needs, which are often culture specific.12 Hence, caregivers’ perceptions and evaluations of the support services provided are of major importance in establishing and optimizing these services.5,13

National and international studies have seldom focused on the care provided and the needs and experiences of the care recipients.14 Moreover, no specific satisfaction measurement tool has been in use.15 Therefore, it is essential to identify the elements of home support services that contribute to family caregiver satisfaction in order to improve home support services.16 This study was carried out with the ultimate goal of improving the home support services provided by the Family and Community Medicine Department at Riyadh Military Hospital. Our main objective was to assess home caregivers’ satisfaction with home care support services and to identify factors associated with their satisfaction.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in the Family and Community Medicine Department at Riyadh Military Hospital. Its home care service division was started in 2005 with about 200 clients. Currently, the division provides home support services to more than 1000 clients with different types of disabling health problems. For this study, we used a cross-sectional survey design.

The study population consisted of all patients registered for home care services at Riyadh Military Hospital and their home caregivers. About 900 patients fulfilled the eligibility criterion of having been registered in the program for at least 6 months, which was stipulated to ensure that participants were familiar with the services sufficiently enough to be able to evaluate them. For caregivers to participate in the study, they needed to be adults (18 years or older), co-living with the patient, and able to be interviewed. A systematic random sample was recruited from those whose names appeared in the home care service division registry. The estimated sample size was calculated based on an expected satisfaction rate of 50% or higher among respondents, with a 95% confidence level and a 13% standard error, using a sample size equation for a single proportion, with finite population correction (Epi-Info, 6.04d). Accordingly, the required sample size, after correction for a 25% dropout rate, was 241 participants.

An interview questionnaire form was designed for data collection. It included questions regarding basic information about the patient and the caregiver, with details about the patient's medical condition and the duration and frequency of requiring home care services. It also included general questions about the caregiver's satisfaction with the services, and a three-point Likert scale for indicating satisfaction with specific procedures and services. Vigorous review of the questionnaire was done to validate the theoretical construct of the satisfaction scale through experts’ opinions in areas of home support, physiotherapy, family and community medicine, internal medicine, health administration, and research. The reliability of the satisfaction scale was assessed by measuring its internal consistency. Its Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.86, indicating good reliability, and was near the higher end of the range of 0.67 to 0.92 reported by Huber et al for a similar questionnaire.17 Data collection was done through telephone interviews. A data collector was trained in interviewing and tested for reliability and consistency. To avoid interviewer bias, the interviewer was not a member of the home care service division, although this could not totally eliminate such bias.

The study protocol was approved by pertinent committees. We followed research ethics principles in the conduct of this study, including informed consent, right to refuse or withdraw, and confidentiality. This study could not include any maneuvers that could harm the respondents. This study would be of benefit through application of its results in improving services provided.

Data entry and statistical analysis were done using the SPSS 16.0 statistical software package. For the satisfaction scale, a three-point Likert scale of 2 (satisfied), 1 (somewhat satisfied), and 0 (dissatisfied) was used, and a simple summative score was calculated for each survey and then converted into a percentage to facilitate interpretation. To identify the independent factors associated with each caregiver's satisfaction score, multiple stepwise backward linear regression analysis was used, and analysis of variance for the full regression model was done. P values less than .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

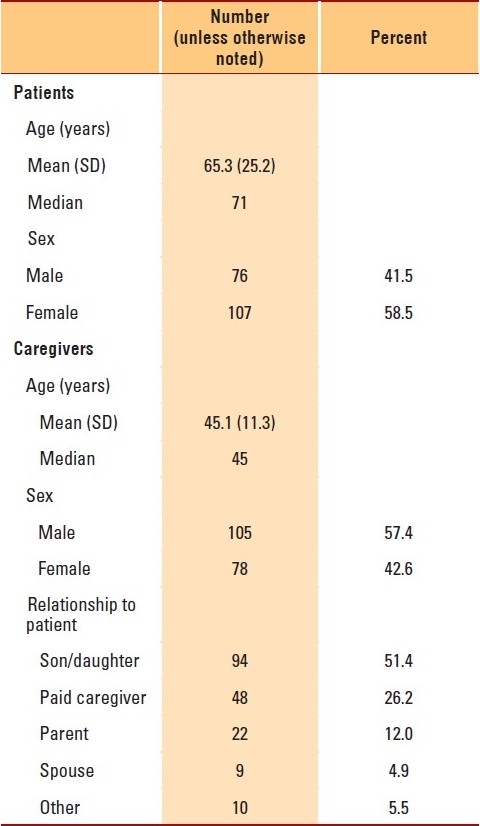

A total of 240 interview forms were filled out; 57 forms were disqualified and discarded from the analysis because of incomplete data, giving a response rate of 76.25%. Most patients were 60 years old or older, with a median age of 71 years; more than half of the patients were women (Table 1). Caregivers were much younger, with a median age of 45 years, and more than half were men. Slightly more than half of the caregivers were the patients’ sons or daughters, whereas spouses represented a small minority (4.9%). Furthermore, about one-fourth of the patients had paid caregivers.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and their caregivers (n=183)

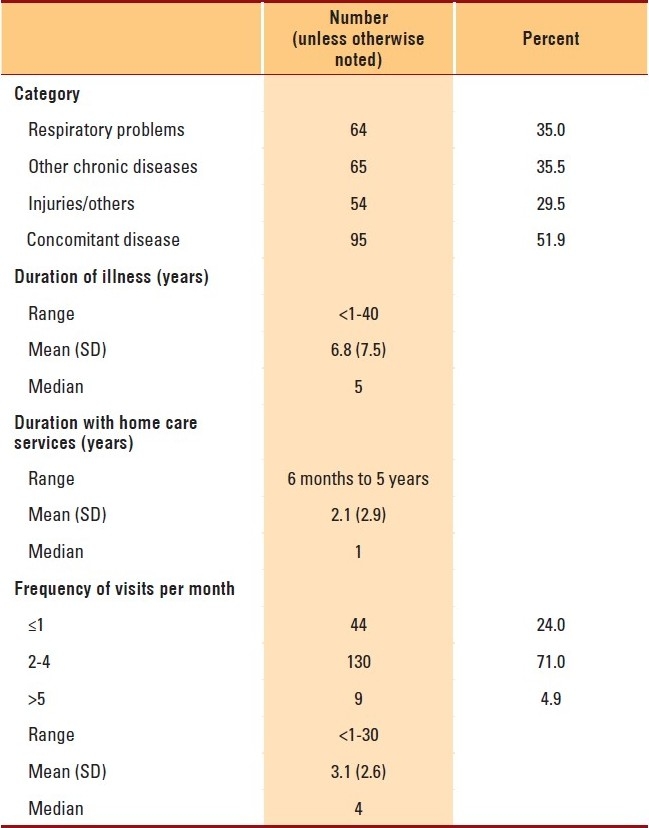

Patients were almost equally distributed among three categories of medical conditions: chronic respiratory problems, other chronic diseases, and injuries or other conditions. The duration of the disabling illnesses ranged from less than 1 year to 40 years, with a median duration of 5 years. Meanwhile, the median duration of the utilization of home care support services was only 1 year. The frequency of home support visits ranged from once daily to once monthly, with a median frequency of 4 days per month (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of illness and utilization of home care services by patients (n=183)

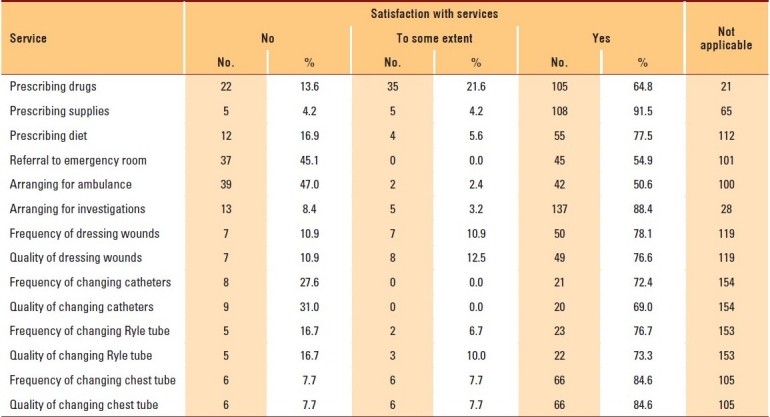

More than 80% of the caregivers agreed that the home care services team provided proper health-care–related support to the patients, in addition to providing the caregivers with self-confidence to administer care (Table 3). Thus almost all of the caregivers expressed a preference for care at home. More than 80% of the caregivers were satisfied with the procedures for prescribing supplies, dealing with chest tubes, and arranging for investigations. On the other hand, about half of them were dissatisfied with arrangements for ambulance transportation and emergency room referrals. Overall, on a scale of 100%, the median level of satisfaction was 90% (Tables 4 and 5). Moreover, 73.2% of caregivers had a satisfaction score of 75% or higher.

Table 3.

Overall opinion of caregivers about home care team (n=183)

Table 4.

Caregivers’ satisfaction with various home care procedures (n=183)

Table 5.

Caregivers’ total satisfaction scores

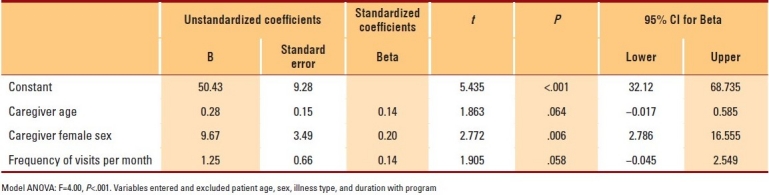

When the factors influencing caregivers’ satisfaction were investigated, statistically significant relations with the type of illness and its duration and the frequency of home visits were revealed. In multivariate analysis, the caregiver's age and gender and the frequency of home visits were all independent factors associated with the satisfaction score (Table 6). As evident from beta coefficient values, an increase in the caregiver's age by 1 year was associated with a 0.28% increase in his or her satisfaction score, whereas each monthly home visit was associated with a 1.25% increase in this score. Furthermore, when the caregiver was female, the satisfaction score was higher by about 10%.

Table 6.

Best-fitting multiple linear regression model for caregivers’ satisfaction score

DISCUSSION

This study was carried out to help improve the services provided by the home care service program at Riyadh Military Hospital. The findings revealed an overall high level of satisfaction among caregivers. However, areas of dissatisfaction were also identified. In addition, the study also identified some of the factors influencing caregivers’ satisfaction.

A telephone-interviewing approach was chosen because of the availability of telephone contacts for all of our registered patients, which would obviate any potential selection bias. This technique was reported to be successful in similar studies.18 It also has the advantage of giving the respondents more freedom to express themselves openly, compared with face-to-face interviews. However, lengthy phone calls could have a negative effect on the completeness of the data. Nonetheless, the response rate (76.25%) was higher than that reported by Huber et al17 in a similar study, where it ranged from 32% to 60%. Analysis of the nonrespondents’ characteristics revealed no significant differences in basic data, which obviates the possibility of differential nonresponse bias.

A major task to be accomplished by home care services, in addition to patient care, is the education of home caregivers in order to enhance their confidence in caring for their patients. In our study, the majority of caregivers were satisfied with this aspect of the services. The finding is in congruence with that of many previous studies that emphasized the importance of this educational role in enhancing satisfaction.19–21

The choice of home care versus hospital care could be influenced by many factors. Some of these factors pertain to logistics, which favor home care; others are related to emotional aspects and family ties. In our study, almost all caregivers preferred home care. Most of the reasons given were related to the psychological well-being of patients and caregivers. In agreement with our finding, Wang et al3 found that home care was the first choice of caregivers in Taiwan. Similarly, in Japan, Numata et al22 reported that 68% of their patients requested transfer to home care.

Most (73.2%) of our caregivers were satisfied with the care provided by the home care services program. This high level of satisfaction could not be attributed to the respondents’ desire to please the interviewer, since the latter was not a member of the program. Furthermore, the respondents freely expressed their dissatisfaction with some areas and services. The finding is in agreement with that of Dahi,8 who reported an overall satisfaction rate of 80.4% among 112 patients who employed home-health-care in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia. Similarly, high levels of satisfaction were reported in the United States23 and in Taiwan.24 On the contrary, lower satisfaction rates were noticed in Korean12 and Finnish25 studies, with the most common reason for dissatisfaction was the caregivers’ perception of having no influence on the services offered, a finding that has also been reported by Tornatore and Grant.16 This reason might explain the discrepancy between those findings and ours, as the majority of our caregivers felt that the home care services team involved them and gave them more confidence in caring for their patients.

Although the level of satisfaction of our caregivers was high, these levels varied for different services. Satisfaction with supplies and investigations was high, but it was low with regard to ambulance and referral services, as well as with how equipment was managed. The findings point to two different types of deficiencies: one related to administrative procedures and the other related to the skills of the home care services team. The approaches to amend these deficiencies are quite different. In contrast, the high satisfaction with supplies is certainly due to their abundant availability; however, there is a problem with their proper utilization. In congruence with this, Paterson et al26 reported that caregiver-identified problems with home care services in Australia included providers’ ignorance about the use of certain medical equipment. Moreover, Katbamna et al27 and Tung and Beck24 in the United Kingdom and Taiwan, respectively, reported on caregivers’ dissatisfaction with the speed of response of home care support teams, coordination of home care services, support given to at-home caregivers, and access to appropriate services.

Caregivers’ satisfaction also varied among services. The least satisfaction was with vocational therapy and physiotherapy. This could be attributed to a shortage of staff in these areas due to the program's commitment to recruit only highly qualified personnel. Additionally, there was some shortage of equipment, along with logistical problems related to transportation. Another plausible explanation is the high expectations of clients. These findings are in congruence with those of Raivio et al25 who found that physiotherapy was the most often needed service as reported by family caregivers. In addition, Kealey and McIntyre5 pointed to the discrepancy between caregivers’ overall satisfaction and their dissatisfaction with the area of occupational therapy. Therefore, these two areas need to be addressed in any plans to improve home care services.

The present study also attempted to identify the factors that could influence caregivers’ satisfaction. Being older and female were two characteristics that positively influenced caregivers. This finding is in agreement with that of Meyers and Gray,28 who reported that being a patient's wife or daughter was significantly related to increased satisfaction with patient care. This gender effect is known in the area of caregiving, as women by nature feel responsible for the care of their family members, even at the expense of their own physical and psychological health. Despite this, most women still consider caregiving to family members or even friends to be a rewarding experience.29 In addition, the positive effect of age can be explained by maturity and a more tolerant attitude gained with advancing age.

Concerning service factors, the frequency of home visits was positively associated with the caregiver's satisfaction score. This is quite plausible, since family members could equate more frequent visits with more care. Furthermore, frequent visits increase the depth of relations between the family and the home support team, which would make the team more responsive to the family's needs. A similar finding was reported by Tornatore and Grant16 in a study in which frequent visiting was one of the positive influential factors on caregivers’ satisfaction.

In conclusion, although most caregivers were satisfied with the services provided by home support, areas of deficiency still exist, mainly related to physiotherapy, vocational therapy, and social services. The strength of the program at Riyadh Military Hospital lies in its ability to give caregivers increased confidence in providing care to their patients. Therefore, the majority of caregivers expressed their preference for home care rather than hospital care. A limitation of the study could be a bias created by collecting data through interviews rather than from self-administered surveys, which might increase the recorded levels of satisfaction. We have tried to minimize this bias by selecting the interviewer from outside the team and by using objective questions in the interview form. Our study implies that family caregivers should be considered as members of the home care team, and they need to be educated and trained in the care of their patients, which would result in increased self-confidence. Home caregiving programs need to provide better facilitation of referral to hospital, especially in cases of emergency, and to improve the quality of physiotherapy, vocational therapy, and social services. Lastly, the home care team members need periodic practical refresher courses to foster their skills in dealing with equipment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morales-Asencio JM, Gonzalo-Jimenez E, Martin-Santos FJ, Morilla-Herrera JC, Celdraan-Manas M, Carrasco AM, et al. Effectiveness of a nurse-led case management home care model in Primary Health Care.A quasi-experimental, controlled, multi-centre study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:193. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutz BJ, Chumbler NR, Lyles T, Hoffman N, Kobb R. Testing a home-telehealth programme for US veterans recovering from stroke and their family caregivers. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:402–9. doi: 10.1080/09638280802069558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang YC, Chung MH, Lai KL, Chou CC, Kao S. Preferences of the elderly and their primary family caregivers in the arrangement of long-term care. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:533–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boumans NP, Berkhout AJ, Vijgen SM, Nijhuis FJ, Vasse RM. The effects of integrated care on quality of work in nursing homes: A quasi-experiment. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:1122–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kealey P, McIntyre I. An evaluation of the domiciliary occupational therapy service in palliative cancer care in a community trust: A patient and carers perspective. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:232–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiese CH, Morgenthal HC, Vossen-Wellmann A, Kriegler M, Klie S, Heidenblut B, et al. Expectations of relatives concerning palliative home care. Pflege Z. 2009;62:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnusson L, Hanson E. Supporting frail older people and their family carers at home using information and communication technology: Cost analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:645–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahi S. Home Health Care Cost Analysis [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomioka K, Kumagai S, Higuchi Y, Tsujimura H, Arai Y, Yoshida J. Low back load and satisfaction rating of caregivers and care receivers in bathing assistance given in a nursing home for the elderly practicing individual care. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2007;49:54–8. doi: 10.1539/sangyoeisei.49.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Cloud GC, Wilson N. Informal primary carers of stroke survivors living at home-challenges, satisfactions and coping: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:337–51. doi: 10.1080/09638280802051721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brazil K, Bedard M, Krueger P, Abernathy T, Lohfeld L, Willison K. Service preferences among family caregivers of the terminally ill. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:69–78. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park YH. Day healthcare services for family caregivers of older people with stroke: Needs and satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:619–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jong JD, Boersma F. Dutch psychogeriatric day-care centers: A qualitative study of the needs and wishes of carers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:268–77. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208008247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCann S, Evans DS. Informal care: The views of people receiving care. Health Soc Care Community. 2002;10:221–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon C, Little P, Birtwistle J, Kendrick T. A questionnaire to measure satisfaction with community services for informal carers of stroke patients: Construction and initial piloting. Health Soc Care Community. 2003;11:129–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2003.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tornatore JB, Grant LA. Family caregiver satisfaction with the nursing home after placement of a relative with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:S80–8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber JP, Saldutto B, Hurny C, Conzelmann M, Beutler M, Fusek M, et al. Assessment of patient satisfaction in geriatric hospitals: A methodological pilot study. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;41:124–31. doi: 10.1007/s00391-007-0454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrow-Howell N, Proctor E, Rozario P. How much is enough? Perspectives of care recipients and professionals on the sufficiency of in-home care. Gerontologist. 2001;41:723–32. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.6.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habermann B, Davis LL. Caring for family with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease: Needs, challenges and satisfaction. J Gerontol Nurs. 2005;31:49–54. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20050601-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tearl DK, Hertzog JH. Home discharge of technology-dependent children: Evaluation of a respiratory-therapist driven family education program. Respir Care. 2007;52:171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakas T, Farran CJ, Austin JK, Given BA, Johnson EA, Williams LS. Stroke caregiver outcomes from the Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK) Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16:105–21. doi: 10.1310/tsr1602-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Numata K, Shirotani N, Iwamoto Y. Home medical treatment and the transfer of medical care of patients at Tokyo Women's Medical University. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2006;33:299–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madeo A, Feld S, Spencer B. Ethical and practical challenges raised by an adult day program's caregiver satisfaction survey. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23:423–9. doi: 10.1177/1533317508320891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tung WC, Beck SL. Family caregivers’ satisfaction with home care for mental illness in Taiwan. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2007;16:62–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raivio M, Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Laakkonen ML, Saarenheimo M, Pietila M, Tilvis R, et al. How do officially organized services meet the needs of elderly caregivers and their spouses with Alzheimer's disease? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22:360–8. doi: 10.1177/1533317507305178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson J, Dunn S, Kowanko I, van Loon A, Stein I, Pretty L. Selection of continence products: Perspectives of people who have incontinence and their carers. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:955–63. doi: 10.1080/096382809210142211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katbamna S, Bhakta P, Ahmad W, Baker R, Parker G. Supporting South Asian carers and those they care for: The role of the primary health care team. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:300–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers JL, Gray LN. The relationships between family primary caregiver characteristics and satisfaction with hospice care, quality of life, and burden. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGuire LC, Anderson LA, Talley RC, Crews JE. Supportive care needs of Americans: A major issue for women as both recipients and providers. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:784–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.CDC6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]