Abstract

Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) is a rare cause of ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome and has characteristic gross and microscopic pathologic findings. We report a case of PPNAD in a 15-year-old boy, which was not associated with Carney's complex. Bilateral adrenalectomy is the treatment of choice.

KEY WORDS: Cushing's syndrome, primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease

INTRODUCTION

Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) is rare and manifests as ACTH-independent Cushing's syndrome (CS). It can be associated with Carney's complex and has a characteristic gross and microscopic appearance.

CASE REPORT

A 15-year-old boy presented with puffiness of face, progressive weight gain, increased pigmentation of skin over groins and arms and episodic headache for 3 years. He was obese, cushingoid and had gynaecomastia and striae over the axillary region. There was no significant family history. The systemic examination was normal. He was hypertensive (170/120 mmHg) at admission and was started on antihypertensives. The magnetic resonance imaging done was reported as bilateral adrenal hyperplasia. Computed tomography of the brain and the pituitary fossa was normal. Serum electrolytes were normal. The 24-h urine cortisol level was 451 and serum ACTH was 5.5 (normal range up to 46). The serum cortisol level at 8 am was 21.2 μg and there was no diurnal variation.

He underwent bilateral adrenalectomy under general anesthesia, through subcostal transverse incision.

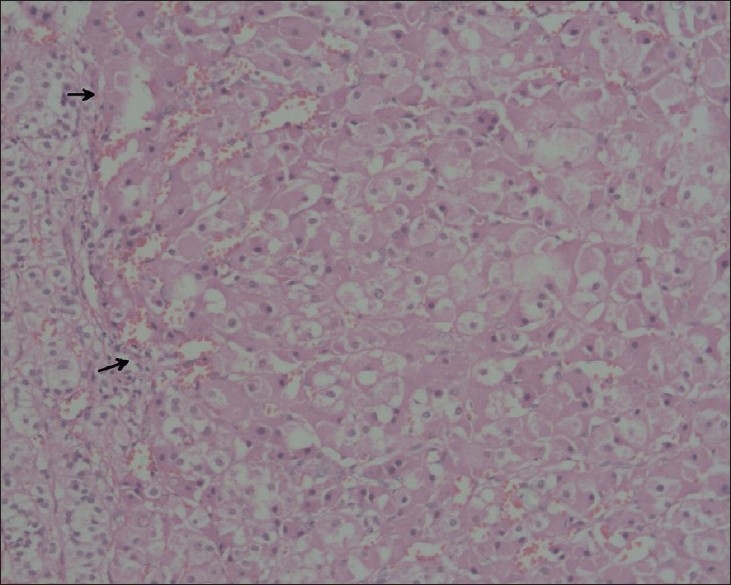

The left adrenal measured 5 cm × 3 cm × 0.9 cm and weighed 4.67 g; the right adrenal measured 4.3 cm × 2.3 cm × 0.4 cm and weighed 2.71 g. The external surface of both adrenals was nodular and black. The cut surface showed black nodules measuring 2–6 mm in diameter with intervening yellow areas [Figure 1]. Sections from both adrenals showed well-circumscribed nodules composed of large polygonal cells with focal anisokaryosis and abundant granular eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm with variable golden-brown pigment [Figure 2]. The intervening cortex showed moderate atrophy. The pigment stained like lipofuscin (positive for PAS and negative for iron stain [Perl's Prussian blue]). Masson Fontana stain was noncontributory. The findings were consistent with PPNAD. The postoperative period was uneventful. Other features of Carney's complex (CNC) were looked for. There were no skin lesions. Echocardiogram was negative for cardiac myxomas. Genetic studies for PRKAR1A could not be done. He was started on hormone replacement therapy. He has been on regular follow-up for 30 months and has not developed any other manifestations of CNC.

Figure 1.

Cut section of the right and left adrenals with multiple small, pigmented nodules

Figure 2.

Microscopy of the adrenals shows cortical nodule (arrows) composed of large polygonal cells surrounded by a rim of normal cortex (H and E, X200)

DISCUSSION

PPNAD is a rare cause of CS. The patients present with ACTH- independent CS. It can occur isolated or as part of CNC. The symptoms are often mild and patients usually present much after the onset of symptoms.[1] The disease usually presents in the second decade, but an age range of 4–44 years has been recorded in the literature.[1,2] There is a female preponderance.[3] The hypercortisolism is resistant to the dexamethasone suppression test.[1,2] The pituitary will be normal on radiological examination. Serum ACTH levels are low or undetectable. PPNAD in children and adolescents can also manifest as variants of CS, like periodic CS (intermittent hypercortisolism) or atypical CS associated with asthenia, muscle wasting and severe osteoporosis.[4] The indolent and/or periodic nature of CS can lead to difficulties in clinical diagnosis. The treatment of choice for PPNAD is bilateral adrenalectomy. Unilateral or subtotal adrenalectomy was followed by recurrence.[2] Bilateral adrenalectomy is indicated to avoid the morbidity associated with CS. PPNAD does not increase the risk for malignancy.[4]

The gross and histological appearance of PPNAD is characteristic and genetic studies are not necessary for a diagnosis. Detailed investigations and careful follow-up and screening, like annual echocardiogram and thyroid and testicular ultrasound at regular intervals, is indicated to detect other manifestations of CNC.[4]

The earlier terms used to describe this condition include primary micronodular adrenal disease, micronodular adrenal hyperplasia, pigmented adrenal micronodular dysplasia and primary adrenocortical micronodular adenomatosis.[3,5] The term PPNAD was first used by Carney in 1984 and later supported by Travis et al.[2,6] The other terminologies were found inappropriate because of the frequent presence of macronodules >1 cm and atrophy of intervening cortex and the absence of hyperplasia.

Typically, both adrenal glands are involved. The size can vary from normal to slightly larger than normal. The typical gross appearance is of multiple nodules of varying sizes and colors studding the cortex. The size can vary from <1 mm to 3.0 cm and the color from yellow tan to black. In rare cases, the nodules cannot be identified grossly. On microscopy, the nodules are separated by atrophic or normal cortical tissue. The nodules are circumscribed, but unencapsulated and varied from small clusters of cells to large nodules filling the entire cortex. The nodules are composed of polygonal cells with eosinophilic, granular to clear cytoplasm. The intracytoplasmic pigment varies in amount and shows staining characteristics of lipofuscin or neuromelanin, positive for PAS, Zeihl Neelsen and Masson Fontana and negative for iron stain. Atypical histological features reported include necrosis, hyperplasia of the internodular cortex, a trabecular growth pattern, mitotic figures and a diffuse rather than a nodular arrangement of cells. These have been reported to be associated with a positive family history of PPNAD.[6] The pathological findings can vary with age, the changes being more marked in the adult or older age group.[6]

More than 90% of the reported PPNAD have been associated with CNC. In fact, PPNAD is one of the major criteria for the diagnosis.[4,7] Among the endocrine manifestations of CNC , PPNAD is the most frequent, seen in about 25% of the patients.[7] Although it may not be grossly evident, histological evidence for PPNAD has been found at autopsy in almost every patient with CNC.[7] Common molecular pathways have been observed in both isolated and CNC-associated PPNAD.[4]

The pathogenesis of PPNAD has recently been well established. Sasao et al. observed that nodules of PPNAD arise from the zona reticularis and demonstrate autonomous hypersecretion of cortisol, supporting the theory of abnormal development of the zona reticularis.[8] Recently, molecular studies have demonstrated inactivating mutations of the PRKAR1A gene on chromosome 17q22-23 or of the PDE11A gene, both of which are key components of the cAMP signaling pathway.[4]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the help rendered by Prof. Noel Walter, M.D, FRCPath, in making the diagnosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi KM, Seu JH, Kim YH, Lee EJ, KIm SJ, Baik SH, et al. Cushing's syndrome due to primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease: A case report and review of literature. Korean J Intern Med. 1995;10:68–72. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1995.10.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shenoy BV, Carpenter PC, Carney JA. Bilateral primary pigmented adrenocortical disease. Rare cause of Cushing's syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:335–44. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasleton PS, Ali HH, Anfield C, Beardwell CG, Shalet S. Micronodular adrenal disease: A light and electron microscopic diagnosis. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:1078–85. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.10.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvath A, Stratakis C. Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease and Cushing's syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab. 2007;51:1238–44. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000800009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweizer-Cagianut M, Froesch ER, Hedinger C. Familial Cushing's syndrome with primary adrenocortical microadenomatosis (primary adrenocortical nodular dysplasia) Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1980;94:529–35. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0940529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travis WD, Tsokos M, Doppman JL, Nieman L, Chrousos GP, Cutler GB, Jr, et al. Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease. A light and electron microscopic study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:921–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantine A, Stratakis Y. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A Type I alpha regulatory subunit (PRKAR1A) in patients with the complex of spotty skin pigmentation, myxomas, endocrine over activity and schwannoma (Carney complex) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;968:3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasano H, Miyazaki S, Sawai T, Sasano N, Nagura H, Funahashi H, et al. Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD): Immunohistochemical and in Situ Hybridisation analysis of steroidogenic enzymes in 8 cases. Mod Pathol. 1992;5:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]