The importance of mental health in the global health scenario has been amply demonstrated. Worldwide, community-based epidemiological studies have estimated that lifetime prevalence rates of mental disorders in adults are 12.2–48.6%, and the 12-month prevalence rates are 8.4–29.1%.[1] In India, the prevalence of mental illness has been estimated to be around 7.3%.[2] Neuropsychiatric disorders account for about 10.8% of the global burden of disorders in the country.[3] As per the Government of India's National Commission on Economics and Health Report of 2005, the prevalence of serious mental illness in the Indian population is at least 6.5%, which, by a rough estimate, would be 71 million people.[4]

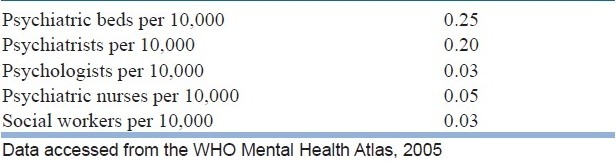

Despite these unnerving statistics, the treatment gap, as measured by the absolute difference between the true prevalence of a disorder and the treated proportion of individuals affected by the disorder, has been found to be very high. A large multicountry survey supported by the WHO showed that 35–50% of the serious cases in developed countries and 76–85% in the less-developed countries had received no treatment in the previous 12 months.[5] One of the major reasons attributed to such a wide treatment gap is the problem of inadequate resources, which is more apparent in developing countries like India. In India, inadequacy exists for infrastructure as well as for human resources. This has been made apparent by the statistics provided by the WHO Mental Health Atlas,[6] as summarized in Table 1. For example, India has 0.20 psychiatrists per 10,000 population. This can be compared with the ideal of 1 per 10,000 population.[7]

Table 1.

Mental health resources in India

The inadequacy has been reported not only in the form of quantity but also in the quality of mental health services. Human rights violations in mental health institutions have been widely criticized as well. The National Human Rights Commission Report[8] (1999) highlights these issues. The report mentions that many institutions still retained a prison-like structure and ambience and prison-like practices such as roll-call and lining up for handover still existed. Exclusively closed wards existed in 59% of the hospitals examined. The building maintenance was unsatisfactory in many hospitals with leaking roofs, eroded floors, overflowing toilets and broken doors. The overall ratio of beds to patients was 1:1.4, indicating that many patients slept on the floor. Some hospitals had no toilets and patients urinated and defecated in the cell, and archaic practices like shaving heads (for both male and female patients) and wearing uniforms were still prevalent.[9]

BRIDGING THE GAP

These deficits in the quantity and quality of mental health services have not been ignored and steps have been taken to bridge the treatment gap, especially to decrease the deficits in human resources. This has been attempted through the National Mental Health Program (NMHP), which envisages integration of mental health care with general health services, especially at the primary care level. Although the District Mental Health Program (DMHP), the basic unit of the NMHP, was launched with huge fanfare, the program failed to gain the desired momentum, and progress has been very slow. Stagnation in sectors like Departments of Psychiatry in medical colleges and mental hospitals has not only robbed the DMHPs of vital managerial support but had also led to an attitude of indifference and apathy among mental health professionals.[10] Even if properly implemented, this program would have the disadvantage that it may have a long latency time before having the desired effect. Other “innovative” strategies have also been proposed to improve the gap, like starting short-duration courses for post-graduate training in psychiatry through distance learning. These may improve the quantity of mental health resources at the cost of quality.

ALTERNATIVE STRATEGY

It has often been assumed that the effective improvement in services can only be done through a marked increase in manpower and infrastructure, which is not possible in the near future. I would beg to differ in this aspect. I propose an alternative strategy to improve the infrastructure and human resources, which can be done in a cost- and time-efficient manner with the available human resources and infrastructure. The following changes are proposed to be a supplement and not as a replacement of the current strategies.

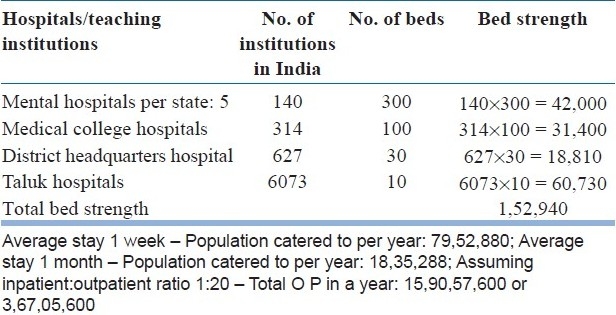

Mental hospitals

As mentioned in various reports, most of the mental hospitals in the country have an archaic infrastructure. Downsizing the bed strength could lead to an improvement in the quality of care. Hospitals running with bed strengths of around 300 patients would function comparatively well. Hence, 300 could be considered as an ideal number to run a mental hospital catering to long-term care. It is necessary to have at least five such mental hospitals per state. Because many of the existing institutions are too old to be amenable for repair, new hospitals may have to be built to replace the old ones. This could be done within a year. Further, the presence of hospitals in five different places within the state instead of a single one could ensure equitable distribution of resources across the state. The state could therefore be divided into five regions. This would provide easy accessibility as well as affordability for the common man. This will also remove the long prevailing stigma attached to specific areas like “kilpauk.” Altogether, this could give rise to an estimated bed strength of 42,000 beds in mental hospitals across the country.

Medical college hospitals

Currently, there are 314 medical college hospitals imparting undergraduate medical education.[11] All medical colleges have a Department of Psychiatry, as per norms set forth by the Medical Council of India. Because most of these departments have adequate manpower, they can be upgraded so that they have at least 100 beds available for inpatient treatment of mental health conditions like mood disorders, schizophrenia, puerperal psychosis, acute disturbance of obsessive compulsive disorder, hysteria, organic brain syndromes and psychiatric emergencies. This excludes beds for drug abuse and alcoholism. Of these, 40 beds could be allotted for male patients, 40 for female patients and 20 for children and adolescents. That would give rise to a bed strength of around 31,400 throughout the country. It could also be necessary to make mandatory that at least one professor, two assistant professors and three senior residents man all psychiatry departments.

District headquarters hospitals

Each District headquarters hospital could have 30 beds each for the management of acute cases, psychiatric emergencies, relapses, attempted suicide and puerperal psychosis. One psychiatrist and two assistants with general medical qualification could man each district hospital. As there are around 627 districts in the country,[12] this would give rise to bed strength of 18,810 beds.

Taluk hospitals

Each Taluk hospital could have 10 beds each for the management of all acute disturbances. A general practitioner trained in psychiatry could man these hospitals. There are around 6073 Taluks in the country,[13] giving rise to a bed strength of 60,730 beds in Taluk hospitals.

Manpower development

Apart from the postgraduate psychiatric training and training of general medical practitioners in psychiatry, there is also a need to increase other paramedical staff, like psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists and nursing professionals, who also come under the ambit of “mental health professionals.” Currently, there are very few institutes imparting postgraduate training to such allied personnel in mental health care. Increasing people with postgraduate training could be an effective strategy. However, this could be time consuming. An alternate strategy would be to recruit nurses, occupational therapists, social workers and psychologists with basic qualification and post them in psychiatry departments for a minimum of 36 months. They could be considered as mental health professionals after a stipulated period of training, say 36 months.

ESTIMATED BENEFITS

By implementing the above strategies, the bed strength could be increased to a total of 1,52,940 in India. Assuming an average stay of 1 week per patient, these beds could cater to up to 79,52,880 patients per year as inpatients [Table 2] if it is 1 month stay per patient then it could cater to 18,35,288 persons per year. Assuming an inpatient:outpatient ratio of 1:20, such a setup could manage around 4–15 crore people per year, i.e. around 16% of the population, which could accommodate the entire prevalence of mental disorders.

Table 2.

Bed Strength in hospitals/teaching institutions in India

By making use of the available resources effectively to cater to the needs of the population to meet the minimum standard, the treatment gap could be abridged within a relatively short period of time. With a proper mental health policy, we could plan for meeting higher standards on par with the developed countries in another 20 years. By adopting such a strategy, the mental health resources in our country could be perceived as being scarce enough and could be upgraded in a time- and cost-efficient manner if planned effectively. Appropriate advocacy is the need of the hour.

In summary, the benefits are as follows:

Small, clean mental hospitals could avoid long stay and promote good turnover.

Mental hospitals in the vicinity of 100 km could promote easy accessibility and acceptability.

When the hospital is small, it tends to get the full attention of the administrators and doctors. (Most of the bigger hospital superintendents are wasting their quality time in protecting and maintaining the property.)

When inpatient facility is made mandatory, the medical colleges would keep the resource professionals available in-house. (Because no inpatient facility is available, the doctors tend to be away from the teaching hospitals and the students also are not trained.)

When the inpatient facilities are available, it necessitates improvement of the infrastructure.

When inpatient services are made available at the primary care level, the patients would obtain full advantage of the treatment.

When the treatment is available at the nearest places, the patients would seek help at an early date. Relapses could be better prevented.

Treatment gap could be abridged.

Mental health promotional activities could be more efficiently done when the above goals are realized.

Overall, the quality of life of the patients could be expected to improve dramatically.

It might look grandiose and magical, but with will and sincerity, I think this could be made a reality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author would like to thank the following in preparing the article: Dr. A. Shyam Sundar, Dr. Sathya Cherukuri, Assistant Professors in SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Kattankulathur - 603 203 India, and Dr. Pragatheeshwar Thirunavukarasu, MD, Resident, University of Pittsburg Medical Centre, USA, for their contributions and suggestions to the content and review of the above manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization: mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: scaling up care for mental, neurological and substance use disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganguli HC. Epidemiological findings on prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2000;42:14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization: Global burden of disease project. Department of Measurement and Health Information. 2004. [Last accessed in 2010 Dec]. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html .

- 4.NCMH Background Papers – Burden of diseases in India, National Commission of Macroeconomics and Health. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization: Mental health atlas: 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thirunavukarasu M, Thirunavukarasu P. Training and National deficit of psychiatrists in India - A critical analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:83–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quality Assurance in Mental Health. New Delhi: National Human Rights Commission; 1999. National Human Rights Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channabasavanna SM, Murthy P. In: The National Human Rights Commission Report 1999: A defining moment, in Mental Health: An Indian Perspective 1946-2003. Agarwal SP, Goel DS, Ichhpulani RL, editors. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gururaj G, Isaac MK. In: Psychiatric epidemiology in India: Moving beyond numbers, in Mental Health: An Indian Perspective 1946-2003. Agarwal SP, Goel DS, Ichhpulani RL, editors. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/Information Desk/Medical College Hospitals/List of Colleges Teaching MBBS.aspx .

- 12. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar 14]. Available from: http://districts.nic.in/dstats.aspx .

- 13. [Last accessed on 2011 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.geopostcodes.com/indiaandregion=4 .