Abstract

Background:

Intimate partner violence against women is seen in all cultures. It has wide-ranging effects on the physical and psychological health of women. In the local language, available questionnaires are either too exhaustive or inadequate to assess domestic violence comprehensively.

Objective:

To develop a Domestic Violence Questionnaire in Malayalam and validate it for married women aged 18–55 years in the local population.

Study design:

Descriptive study – Validation of questionnaire.

Materials and Methods:

A 29-item questionnaire, to identify domestic violence over the past 1 year, was developed in the local language, by selecting items from two other questionnaires and based on expert opinion. Item reduction was done after pilot testing. Then, this 25-item questionnaire was administered to 276 married women aged 18–55 years. Reliability and validity were estimated. Factor analysis was done for item reduction. Poor-loading, wrong-loading and cross-loading items were removed from the questionnaire. Taking the subjective perception of the participants regarding themselves experiencing domestic violence as the gold standard, a Receiver Operator Characteristic curve was drawn to decide the cut-off score with optimum sensitivity and specificity.

Results:

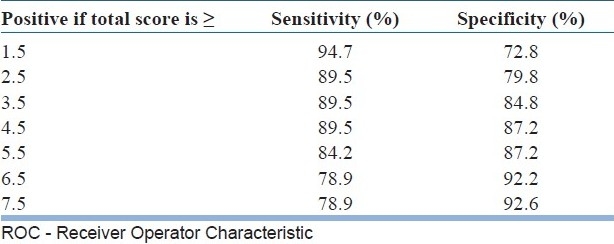

The final questionnaire had 20 items – 13 items for psychological and 7 items for physical violence. Internal consistency reliability was 0.92. At a cut-off score of 5, sensitivity was 89.5% and specificity 87.2%.

Conclusions:

The Domestic Violence Questionnaire in Malayalam has adequate psychometric properties to identify intimate partner violence against women in the local population.

Keywords: Domestic violence, intimate partner violence, questionnaire, women

INTRODUCTION

Violence against women constitutes a violation of the rights and fundamental freedom of women. The United Nations defines violence against women as “any act of gender based violence that results in, or is likely to result in physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life”.[1] It is predominantly women who experience such abuse and men who perpetrate this violence. This scenario prevails across all countries, cultures, religions and sectors of society.[2] Spousal violence has wide-ranging effects on the physical and psychological health of women. Recent studies in both developed and developing countries show that exposure to domestic violence is strongly associated with attempted suicide in women.[3]

Rationale of the study

In 48 population-based studies conducted around the world from 1982 to 1999, between 10 and 69% of women reported physical abuse by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.[4] In a large multi-site household survey conducted in India by the International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN), about 50% of women reported exposure to a minimum of one act of domestic violence at least once in their married life – 43.5% reported at least one psychologically abusive behavior and 40.3% at least one form of violent physical behavior.[5] The National Family Health Survey-3, conducted in India during 2005–06, reported that 34% of all women aged 15–49 years had experienced violence at any time since the age of 15 years and 19% experienced the same in the 12 months preceding the survey.[6] Eighty-five percent of those ever-married women, who had experienced violence since the age of 15 years, reported their current husband to be the perpetrator. The prevalence of emotional, physical or sexual violence by current husband was found to be 39.7%. The least prevalence was reported from Himachal Pradesh (6.9%) and the highest from Bihar (60.8%), with Kerala reporting a prevalence of 19.8%.[6]

The WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women focused primarily on violence experienced by women, from an intimate partner.[7] This study found significant association between lifetime experience of partner violence and both self-reported poor health and specific health problems in the previous 4 weeks. Mental health problems, emotional distress and suicidal behavior were common among women who had suffered partner violence.[8] Psychological consequences of intimate partner violence include depression, anxiety disorders, chronic mental illness and suicidal attempt.[9] A study conducted in Spain found that 58.7% of physically or psychologically abused and 43.6% of psychologically abused women had experienced suicidal thoughts, while 34.7 and 12.7%, respectively, had suicidal attempts. These were significantly higher than the observations made among non-abused women.[9] A study done in Indian women showed increased risk of poor mental health in women reporting any physical violence (OR 2.2, 95% CI 2.0–2.5) or all forms of physical violence (OR 3.5, 95% CI 2.94–3.51).[10] Domestic violence is found to be a contributing source of psychiatric morbidities like depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and even substance abuse in women, but not so in men.[11] The WHO study clearly demonstrated that violence against women was widespread and deeply ingrained, and had serious impacts on women's health and well-being. One of the recommendations drawn from the findings of this study was the need to monitor for violence against women, using both regular surveys and routine data collection in different service points.[8]

A variety of questionnaires, both oral and written, have been designed to screen for intimate partner violence. The Conflict Tactics Scale is considered the gold standard among the screening tools for domestic violence.[12] The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2) measures violence against a partner in a dating or marital relationship.[13] Other common questionnaires include the Partner Violence Screen, the Women Abuse Screening Tool, the Two-Question Screening Tool and the Composite Abuse Scale.[14–19] The WHO multi-country study used a standardized structured questionnaire, built on the tradition of the Conflict Tactics Scale, to assess physical and sexual violence and controlling behavior by an intimate partner.[20] Many of the tools are either too comprehensive for practical use in a clinic, or too brief, often lacking adequate sensitivity.[21,22]

A multi-center study conducted by the International Clinical Epidemiology Network in India – Study of Abuse in the Family Environment (India SAFE) study – at seven medical schools in New Delhi, Lucknow, Bhopal, Nagpur, Chennai, Trivandrum and Vellore used a family questionnaire which assessed physical and psychological violence by a husband against his wife also.[10] The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) Woman's Questionnaire included items on physical, sexual and emotional violence.[23] Both these questionnaires were available in the local language, Malayalam. But the former was too exhaustive for use in clinical settings. The latter included questions which assessed physical, psychological and sexual violence, but the translated version had a few inaccuracies. Hence, it was found necessary to develop and validate a comprehensive questionnaire in Malayalam to assess domestic violence. For this, domestic violence was conceptually defined as any reported violence, whether physical, sexual or psychological, perpetrated by a husband against his wife.

Objective

To develop a self-administered Domestic Violence Questionnaire in Malayalam for the assessment of intimate partner violence against women, over the past 1 year, and to validate it for the local population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Descriptive study – Validation of questionnaire.

Study setting and study population

A Domestic Violence Questionnaire was developed primarily by selecting items from two other questionnaires in the local language.[10,23] Validation was done for the local population of Thiruvananthapuram, in community setting. The study population comprised married women aged 18–55 years. The study sample was constituted by employees from the headquarters of a bank and members of various units of Kudumbashree, selected purposively from Thiruvananthapuram district. Kudumbashree is a women-based poverty eradication program initiated by the Government of Kerala in 1998, with the active support of the Government of India and National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development.[24] Kudumbashree units are neighborhood groups, constituted exclusively by women members.[24] Kudumbashree units were selected purposively – three rural, two urban, one semi-urban and two coastal units – to represent the population of Thiruvananthapuram district. All the married women from both these settings, who were in the age group 18–55 years and gave consent to participate, were included in the study sample. The sample size was 276, which included 234 women from different Kudumbashree units and 42 bank employees. The study was conducted over a period of 45 days from September 2009.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using MS Excel and SPSS version 11. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability were assessed along with face and content validity. Construct validity was demonstrated through factor analysis. Principal component factor analysis was done for the initial extraction of factors and varimax rotation to bring about a simplification of the initial solution. Criterion validity was established, taking the subjective perception of the participant as the gold standard.

Development of domestic violence questionnaire

The Domestic Violence Questionnaire was intended to be a short, simple, self-administered, discriminative instrument. It was designed with the intention of capturing the major dimensions of the concept of domestic violence – physical, sexual and psychological violence. The summary scores were expected to be amenable to statistical analysis, with adequate reliability and validity.

Item generation

Items to assess domestic violence were selected from two questionnaires in the local language – the National Family Health Survey-3 Questionnaire[23] and the India SAFE Questionnaire.[10] Eleven items were selected from the former, nine items from the latter, and six items commonly from both. Qualitative interviews were done with experts – psychiatrists, clinical psychologist and social workers – to assess the dimensionality and comprehensive coverage of items. Three items were added based on expert opinion. Thus, a 29-item questionnaire was developed to assess domestic violence over the past 1 year. There were 17 items to assess psychological violence and 12 items to assess physical (including sexual) violence. The items were worded without ambiguity and sequenced such that the more threatening ones came later in the questionnaire. Each item was scored from 0 to 4 (0: never, 1: once/twice, 2: 3–5 times, 3: 6–10 times, and 4: 11 times or more). The questionnaire was pre-tested among peers and experts to ensure face and content validity.

Pilot testing and item reduction

After obtaining clearance from the Human Ethical Committee of our institution, pilot testing was done on 30 married women aged 18–55 years. Descriptive statistics was calculated using MS Excel. The items which showed maximum skewing were identified. Four items showing very high endorsement frequency (>95%) were deleted as they could not contribute to the discrimination ability of the instrument.

Validation of 25-item questionnaire

After item reduction, the 25-item questionnaire was administered to the study sample. The subjective perception of the participants regarding themselves experiencing domestic violence was also assessed. This item was not a part of the proposed Domestic Violence Questionnaire. It was scored as yes/no and was used to decide a cut-off score for the questionnaire. The questionnaire was re-administered to 30 participants within a span of 2 weeks for test–retest analysis.

RESULTS

The age of the study sample ranged from 22 to 55 years. The mean age was 40.1 years (standard deviation (SD) 8.24) and the median age was 40 years. Majority of the study population had studied up to high school (40.2%). Almost 19% each had studied up to primary school and pre-degree/plus two, while 20% had degree/post-graduate education. Only 2.2% of the population was illiterate, which was in accordance with the educational standards of Kerala.

The total scores of the questionnaire ranged from 0 to 79. The mean of the total score was 3.9 (SD 10.11) and the median was 0.

Reliability and validity

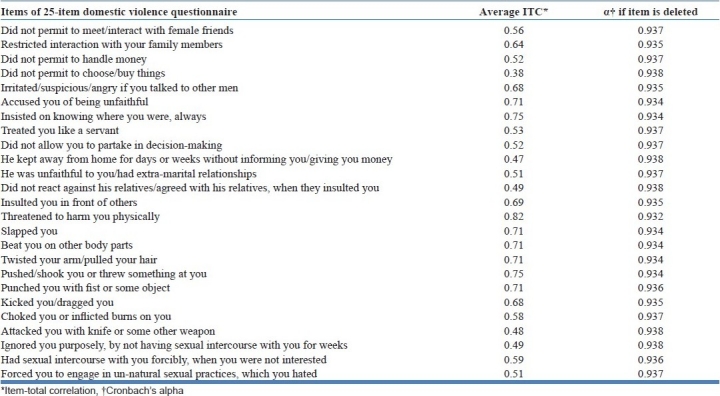

After entering the data in MS Excel, cleaning and editing was done. Data analysis was done using SPSS version 11. Item analysis was done and correlation matrix obtained. Estimated common inter-item correlation was 0.38. Item-total correlation was found to be greater than 0.2 for all the items [Table 1]. The internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach's alpha) for the 25-item questionnaire was 0.94. Test–retest reliability was 0.96 (95% CI 0.93–0.98), when the questionnaire was re-administered within a period of 2 weeks. Further, factor analysis was done to demonstrate construct validity. Criterion validity was established by plotting Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve.

Table 1.

Item-total correlation of 25-item domestic violence questionnaire

Factor analysis and item reduction

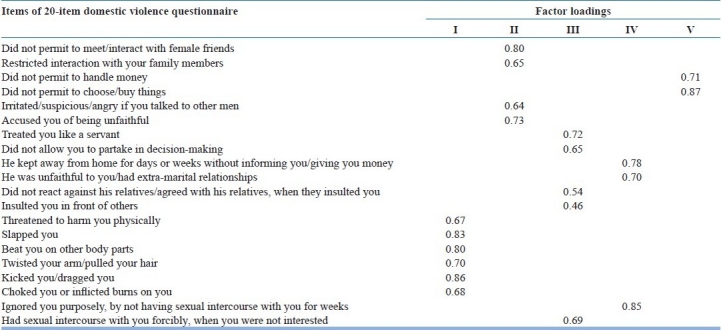

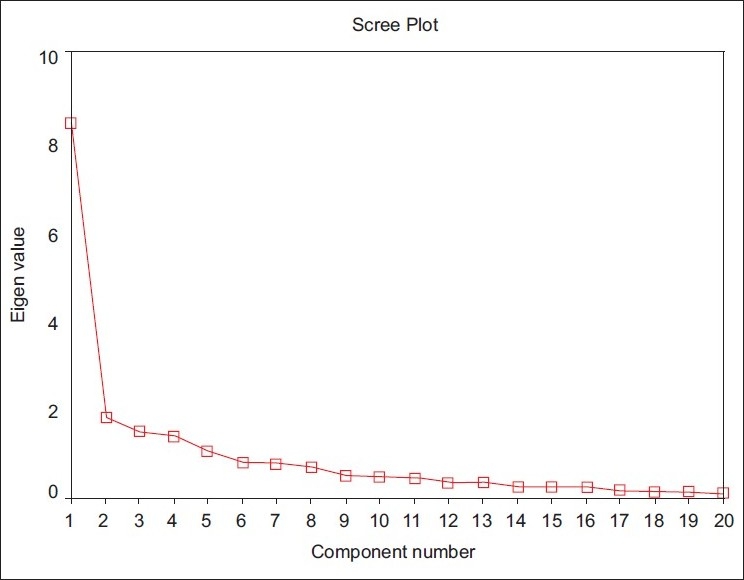

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.84. Bartlett's test of sphericity was significant (χ2=5605.34, df 300, Sig.=0.0001). This showed that the data were amenable to factor analysis. Principal component factor analysis was done to extract the initial factors. An orthogonal rotation of the initial factor structure was done by varimax method [Table 2] to maximize the variance explained by each factor independently and to obtain simpler results, which could be interpreted more readily. Item reduction was done by removing those items with poor loading (less than 0.35) initially, followed by those which loaded wrongly and showed cross-loading. Altogether, five items were removed. One item with cross-loading was retained in the factor in which it showed maximum loading, as it was considered to be clinically significant. After removing every item, internal consistency reliability was assessed. There was no significant difference in the reliability after removing each of these item variables. Cronbach's alpha, after removing five items, was found to be 0.92.

Table 2.

Rotated component matrix of the 20-item domestic violence questionnaire after factor analysis and item reduction

Rotated factor structure of the 20 items yielded five factors, with Eigen value greater than 1 as evidenced by scree plot [Figure 1]. These factors were labeled as follows: I, physical violence; II, controlling behavior; III, insulting behavior; IV, neglecting behavior; and V, economic restriction. Together, they determined 71.14% of the variance among the observed variables. The final questionnaire had 20 items – 13 items for psychological violence (including factors identified as its variants) and 7 items for physical violence. The rotated component matrix of the 20-item questionnaire is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Scree plot showing factors with Eigen value more than one

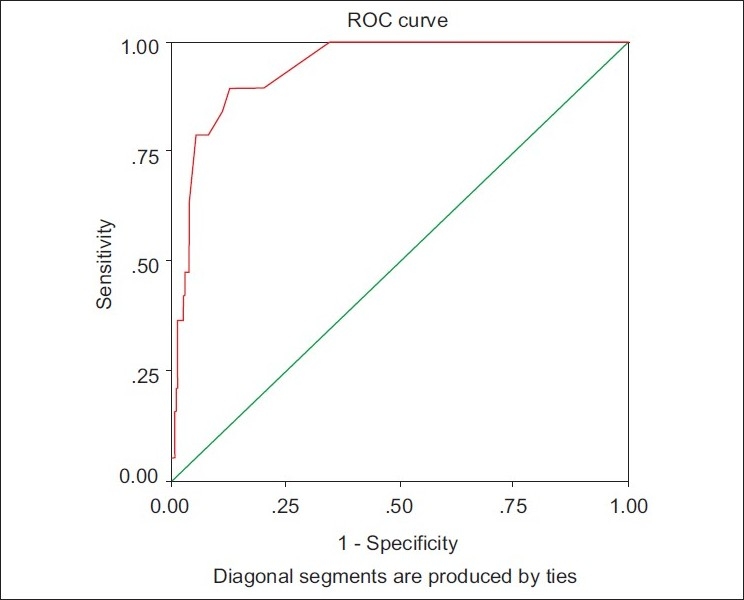

In the absence of an ideal gold standard in the local language, the item to assess the subjective perception of domestic violence by the participant was used as the gold standard to decide a cut-off score for the questionnaire. An ROC curve was drawn with the total score of the questionnaire against the subjective perception of the participant as the gold standard [Figure 2]. Area under the curve was 0.942. Using the ROC curve, a score of 5 was taken as the cutoff. At this cutoff, both sensitivity and specificity were optimum, i.e. 89.5 and 87.2%, respectively [Table 3].

Figure 2.

Receiver Operator Characteristic curve with subjective perception as gold-standard

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity of the 20-item questionnaire at different total scores, as derived from ROC curve

DISCUSSION

This 20-item Domestic Violence Questionnaire had internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of 0.92, which is greater than the acceptable level of 0.7. The test–retest reliability was 0.94, when re-administered within a period of 2 weeks. Greater than 85% sensitivity and specificity were seen at a cut-off score of 5. That the retained factors explain more than 70% of the total variance seems to be a desirable property of the instrument.

It is found that, in a majority of studies regarding domestic violence, having “ever” been exposed to physical or psychological abuse during the lifetime or in the past 1 year is assessed.[10,25–29] In this study, by incorporating the subjective perception of the participant to decide a cut-off score for this questionnaire, a more realistic assessment of domestic violence has been made.

The items of this questionnaire were conceived to represent the domains of physical, sexual and psychological violence. But factor analysis revealed five factors. Items for physical violence were found to load under the same factor. But items intended to measure psychological violence loaded under different factors, which could be identified as sub-domains of the same. Those items which were intended to assess sexual violence were subsumed under different sub-domains of psychological violence. This could be due to the fact that sexual violence has a psychological component also. All the factors derived by factor analysis could be labeled by the researcher.

This questionnaire was used for another study, which hypothesized domestic violence to be a risk factor for attempted suicide in married women. In that study, domestic violence was found to increase the risk of attempted suicide in married women of reproductive age group by almost four times.[30] This provides further evidence for the construct validity of the Domestic Violence Questionnaire.

Limitations

As the two questionnaires available in the local language on domestic violence were the sources for majority of the items in this questionnaire, convergent validity could not be assessed. Due to lack of questionnaires to assess a dissimilar construct, divergent validity also could not be assessed.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the analysis of the psychometric properties, it can be concluded that the 20-item Domestic Violence Questionnaire is a reliable and valid tool for use among the married, women population of Thiruvananthapuram. At a cut-off score of 5, the questionnaire shows favorable sensitivity and specificity in identifying domestic violence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ramdas Pisharody, Principal, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, and Dr. Rajamohanan K, Director, Clinical Epidemiology Resource and Training Centre Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, for the invaluable guidance given. We are grateful to Dr. Kumar KA, Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry, Gokulam Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, Dr. Ramachandran A, Professor of Psychiatry, SUT Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, and Dr. Janaki KN, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, for the valuable suggestions given in developing the questionnaire. We express our gratitude to Dr. Anil Prabhakaran, Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, for his support and permission to publish this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Resolution A/RES/48/104. “Declaration on the elimination of violence against women” adopted by the UN General Assembly. 1993 Dec 20; [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Republic of Moldova. 2006. Response to domestic violence in pregnancy- Report. Making pregnancy safer and gender mainstreaming; 2005 April 12- 13; pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V. In: Gender and health research series. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. Patel V. Gender in mental health research; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heise L, Garcia- Moreno C. Violence by intimate partners. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 87–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahuja RC, Bangdiwala S, Bhambal SS, Jain D, Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, et al. Domestic violence in India: A summary report of a multi-site household survey. Washington DC: International Clinical Epidemiology Network and International Centre for Research on Women; 2000. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06. I. India: Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International; pp. 507–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia- Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. In: WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. Definitions and questionnaire development; pp. 13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: Summary report of Indian results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. pp. 15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falsetti SA. Screening and responding to family and intimate partner violence in the primary care setting. Prim Care. 2007;34:641–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Suresh S, Ahuja RC. Domestic violence and its mental health correlates in Indian women. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:62–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrensaft MK, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Is domestic violence followed by an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among women but not in men.A longitudinal cohort study? Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:885–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunter J. Intimate Partner Violence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:367–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss MA. Conflict Tactics Scales. In: Jackson NA, editor. Encyclopedia of domestic violence. New York: Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group; 2007. pp. 190–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, Abbott JT. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown JB, Lent B, Brett PJ, Sas G, Pederson LL. Development of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool for use in family practice. Fam Med. 1996;28:422–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFarlane J, Greenberg L, Weltge A, Watson M. Identification of abuse in emergency departments: Effectiveness of a two-question screening tool. J Emerg Nurs. 1995;21:391–4. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(05)80103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegarty K, Sheehan M, Schonfeld C. A multi-dimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:399–415. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The composite abuse scale: Further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multi-dimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence Vict. 2005;20:529–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, Boyle M, McNutt LA, Worster A, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:530–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi- country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zolotor AJ, Denham AC, Weil A. Intimate Partner Violence. Prim Care. 2009;36:167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Control and Prevention; 2007. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in health care settings: version 1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06. II. India: Mumbai: IIPS; 7. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International; pp. 61–133. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadiyala S. Food Consumption and Nutrition Division no. 180; May 2004. Washington D.C: International Food Policy research Institute; 2004. Scaling up Kudumbashree- collective action for poverty alleviation and women empowerment; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegarty K, Gunn J, Chondros P, Small R. Association between depression and abuse by partners of women attending general practice: Descriptive cross-sectional survey. BMJ. 2004;328:621–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varma D, Chandra PS, Thomas T, Carey MP. Intimate partner violence and sexual coercion among pregnant women in India: Relationship with depression and post traumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maselko J, Patel V. Why women attempt suicide: The role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:817–22. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chowdhary N, Patel V. The effect of spousal violence on women's health: Findings from the Stree Arogya Shodh in Goa, Indian. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:306–12. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.43514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellsberg M, Jansen HA, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia- Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60522-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indu PV. Dissertation for M. Phil in Clinical Epidemiology. Kerala, India: University of Kerala; 2010. Domestic violence as a risk factor for attempted suicide in married women aged 18 to 45 years: A case-control study. [Google Scholar]