“Draw what can’t be seen, watch what's never been done, and tell thousands about it without saying a word.”

- Frank Netter, M.D.

When I was a medical student, I found the medical illustrations accompanying voluminous texts extremely helpful in aiding my understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pathology. Many years later, as a practicing physician, I still find such illustrations enormously useful, especially when viewing technical and digital images of various disease processes. Indeed, the proverb, “One picture is worth more than a thousand words” is right on tract.

BACKGROUND

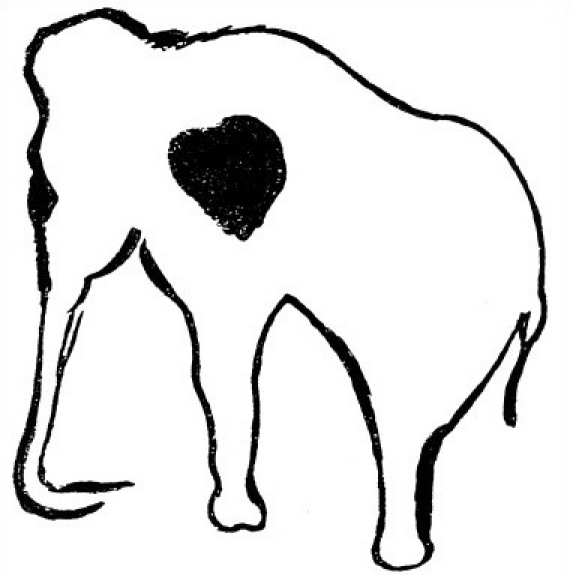

Before there were written words, there were pictograms – pictorial representations of objects. Pictorial representations date back thousands of years and predated history. The ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, and Indians recorded medically related illustrations on stone, metal, ceramic, porcelain, bamboo, and silk. Historians claim that the first pictorial signs appeared 30,000 years ago in the form of cave paintings.[1] One remarkable drawing in a prehistoric cave (c.15000 BC) depicts a mammoth with a leaf-shaped dark area where the heart should be. If it were truly the drawing of a heart, (which it probably was), it would be the first anatomical illustration.[2] Prehistoric societies were primarily hunting societies and the heart must have been the organ that attracted the attention of man from earliest times because he found it beating as long as there was life and he soon must have discovered that the best way to kill an animal was to spear it through the heart.[3] The drawing probably also served as teaching material to young hunters. I can imagine an older and seasoned hunter using such illustration to coach young hunters which part of the animal they should direct their arrows.

Cave-drawing of a mammoth in El Pindal cave in Spain, with dark smudge at shoulder, which may represent the heart. The drawing may have been used to teach young hunters where to aim their arrow or spear. (Photo Source: Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. Medicine: An Illustrated History. New York. Harry N. Abrams Inc:1987.

Knowledge of anatomy in early societies was minimal because dissection of the human body was forbidden. The concept that the human body housed the soul and therefore sacred was prevalent in the ancient world (Greece, Egypt, and China) and persisted well into the 19th century.

Alexandria in antiquity

Alexandria, Egypt is an important city in the history of medicine. Radical new thinking and understanding of disease processes came out from the fertile intellectual and scientific climate prevailing in Alexandra from the 3rd century B.C. to the 7th century A.D. During that period, Alexandria was a place of inspiration. There, King Ptolemy, who ruled Egypt from 323 – 282 BC, established the Alexandrian Museum and the Great Library of Alexandria, fabled in antiquity for its treasures of wisdom. The king mandated the “collection of all books in the inhabited world.” He personally sent letters to “all the sovereigns and governors on earth” requesting that they furnish works by “poets and prose-writers, rhetoricians, and sophists, doctors and soothsayers, historians and all the others too.” Agents were sent to scout the cities of Asia, North Africa, and Europe, and were authorized to spend whatever was necessary.[4]

The library gave poets, historians, musicians, mathematicians, astronomers, and scientists an opportunity to live and work under royal patronage. The results were grandly impressive: Euclid worked out the elements of geometry; Ptolemy mapped the heavens; Eratosthenes determined the circumference of the earth; Ctesibius designed a waterclock and built the first keyboard instrument (perhaps the prototype of our present computer keyboard); Archimedes refined his theory on the weight and displacement of liquids and gases; Callimachus, the famous poet and librarian, catalogued the huge collection of scrolls; Zenodus produced authentic versions of Homer's epics by collating every known text that he could find.[4] Alexandria became world-renowned as a great center of Greek learning.

The intellectual and scientific ferment taking place in Alexandria attracted medical talent. Both the medical school and the medical research in Alexandria were the most famous in antiquity. At Alexandria, dissection of corpses was permitted and was a regular practice, for the first time in history.[4]

The two outstanding medical investigators in Alexandria were Herophilus (c. 330 – 260 B.C.) and Erasistratus (c. 304 – 250 B.C.). They were the two leading professors of the “new medicine” that sprouted and flowered in Alexandria. In contrast to the physical observations and disease descriptions of the Hippocratic School, Herophilus was concerned with direct knowledge and precise terminology. In order to achieve this, Herophilus embarked upon a new study of the human body, based on anatomy and human dissection. Tertullian, a prolific early Christian author in Rome, indignantly denounced Herophilus’ pioneer work: “Herophilus the physician or that butcher who cut up hundreds of human beings so that he could study nature”.[4]

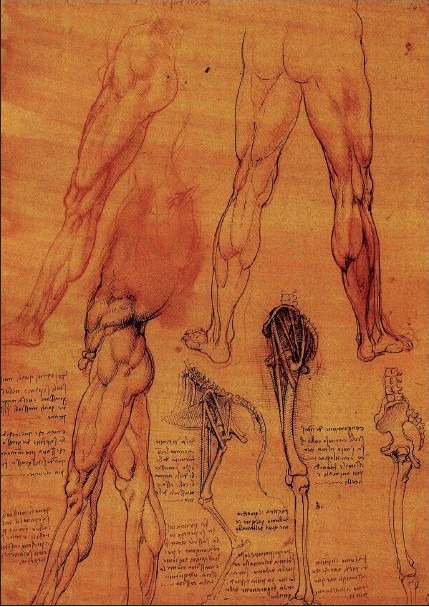

Surface and topographical anatomical views of the lower extremity by Leonardo Da Vinci. (Photo Source: Clayton M. Leonardo Da Vinci. The Anatomy of Man. Drawings from the Collection of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Houston. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and Bulfinch Press: 1992)

Herophilus was a Greek physician and was the first to base his writings on authorized, legitimate dissection of the human body. He recorded his observations in On Dissections. Despite the bitter criticism of the Roman Tertullian for dissecting human corpses, Herophilus is considered the father of anatomy. It has been said that Herophilus occasionally performed dissections in public (!). I suppose one can forgive his weakness in giving in to the elemental human need for showmanship. His contemporary, Erasistratus, is also best known for his work on human cadavers and his knowledge of the human body. Erasistratus is considered the father of physiology.

The medical school in Alexandria was in the forefront in the move towards a “scientific” medicine. The contributions of Herophilus to our knowledge of anatomy and medical terminology are enormous. Through his anatomical studies on the nervous system, Herophilus proved that the brain and not the heart was the seat of intelligence, a revolutionary breakthrough for that period since it contradicted a prevailing Aristotelian concept which stated that the heart is the seat of intelligence, rational thoughts, emotions, and desires.

Unfortunately, neither Herophilus nor Erasistratus illustrated or made drawings of their anatomical observations from their dissections. Their writings have been lost and most of our knowledge of these two is derived from commentators, especially Celsus and Galen.

Galen's shadow: “Though he sees the truth, he does not use it.”

Ancient philosophers were especially concerned with the what, why, and how of things. The subject that preoccupied them was the nature of the human soul – the life-principle or substance of every living being; in other words the spirit: where is it located? In the heart? In the brain? What is the function of each organ? Through observation and experimentation they struggled to sort out which organ was responsible for what function.

Where is the center of emotions and feelings? Where is the seat of intelligence? These issues were a source of confusion in ancient times. Traces of such confusion live on in the tradition of metaphorically describing feelings and emotions as if they actually originated from the heart. This tradition has enriched our language and literary heritage. The Babylonians thought that the liver was the most important organ of the body because it was used for divination, which was an integral part of their daily life. Hence, the liver was thought of as the center of feelings and emotions; the heart was the center of the mind; the stomach was the center of strength and courage; and the uterus was the center of motherly love.[5]

We now know that the heart is only a pumping organ and that the brain is the center of thoughts, emotions, intelligence, and cognitive and motor function. The heart perfuses the brain and all the other organs of the body. The heart and the brain are closely interdependent and interrelated. The brain in turn exerts some control over cardiac function.[5] The famous Arab philosopher from Andalusia, Ibn Rushd (AD1128 - 1198), who is known as Averroes in the West, succinctly stated in his book Kulliyat (General Medicine): “The brain is the master and the heart serves the brain with nourishment”.[6]

The ancient Egyptians cited the heart as the center of feelings and emotions,[4] which later Greek and Arab physicians adapted. Aristotle believed in it; and so did Galen (c. 130 – 200 A.D.). There was even a time when it was believed that the heart was the center of thoughts and reasoning until Herophilus, as a result of his anatomical studies on the nervous system, proved that the brain and not the heart was the seat of intelligence.[7] Galen believed in Aristotle and Herophilus. In contrast, the stoics, a philosophical school of thought in classical Greece, believed that the human soul pervades and breathes through all the body – informing and guiding it, a doctrine that Galen strongly opposed. Galen wrote of Chrysippus, the leader of the stoics, “Though he sees the truth, he does not use it”.[8]

Galen, in his writings appreciated and admired the work of Herophilus: “his knowledge of facts acquired through anatomy was exceedingly precise, and most of his observations were made not, as in the case of most of us, on brute beasts but on human beings themselves”.[5] Galen believed that dissection was essential to medical understanding.

Galen is a giant in the history of medicine and casts a long shadow. His medical theories dominated European medicine for 1500 years. He was a Greek physician who practiced in Rome, becoming physician to five Roman emperors. He was prolific and wrote hundreds of treatises, compiling all significant Greek and Roman medical thought, and adding his own discoveries and theories, foremost of which was the humoral basis of disease: illness was caused by an imbalance of the four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. He showed, through experimentation, that the arteries carried blood, and not air, as was commonly believed. He almost discovered the circulation but failed to make the correct deductions from the data available to him.[8]

Andreas Vesalius

Many historians of medicine have analyzed Galen's writings, trying to understand why, brilliant as he was, he did not make the conclusion that the heart is only a pump organ, devoid of emotions or feelings. One partial explanation, according to them, was that Galen was more concerned with proving the stoics wrong, and once he proved that reason or rational thought resided in the brain, he went no further, and thus failed to recognize the true role of the heart as merely a pump organ.[8] In retrospect, we can also claim, with a touch of irony and using Galen's tongue, that though he [Galen] saw the truth, he failed to use it.

Galen did not illustrate with drawings or sketches his writings and observations on anatomy based on vivisections of apes or the anatomical knowledge he gained from treating wounded gladiators. I wonder if in illustrating his theories with sketches and drawings, he would eventually have seen the light – that the heart was only a circulatory pump, as Harvey did 1400 years later? It is possible...

Galen's writings contained many erroneous descriptions of human anatomy because he performed dissections on apes and extrapolated his findings to humans. It is possible that the errors might have been picked up earlier and rectified by subsequent investigators had there been drawings and sketches to accompany the voluminous written texts. Had that been the case, it makes me wonder what advances, what leaps we would have made in our current understanding of the heart. Where would we be now? It is a tantalizing thought.

Artists and physicians in Renaissance Europe

Artists were instrumental in bringing about a reinterpretation or rebooting of medical dogma that have been recycled, unchanged, throughout the centuries. This period in European history is termed “renaissance”, from French, meaning “rebirth.” It began in Italy, in the 14th century and lasted through to the 17th century. It was a European cultural movement that spread from Italy to the rest of Europe and encompassed the growth and blossoming of literature, science, art, religion, and politics as well as a re-awakening and re-discovery of the learning of antiquity. Artists began to reject the authority of Galen and rediscover the classical traditions of Greek art: observation and portrayal of natural forms. Artists wanted to make more realistic art and they used human anatomy to depict an accurate human form and to see how systems (like muscles) worked.

Paintings, drawings, and sculptures of the human body during the Renaissance were imbued with energy and realism, and hence, it is believed that artists like Raphael (AD 1483 – 1520) and Michelangelo (AD 1475 – 1564) may have performed anatomical dissections. Leonardo da Vinci (AD 1452 – 1519), the celebrated master artist as well as great inventor, engineer and scientist made numerous observations and experiments that he recorded in his sketches accompanied with his notes (written backwards!).[9] Very few people know of his drawings on the anatomy of man. Da Vinci was one of the most original and perceptive “anatomists” of his time. He drew detailed illustrations of bones, muscles, and organ systems with elaborate and insightful observations. He combined techniques familiar to him from engineering and architecture to represent the human body.

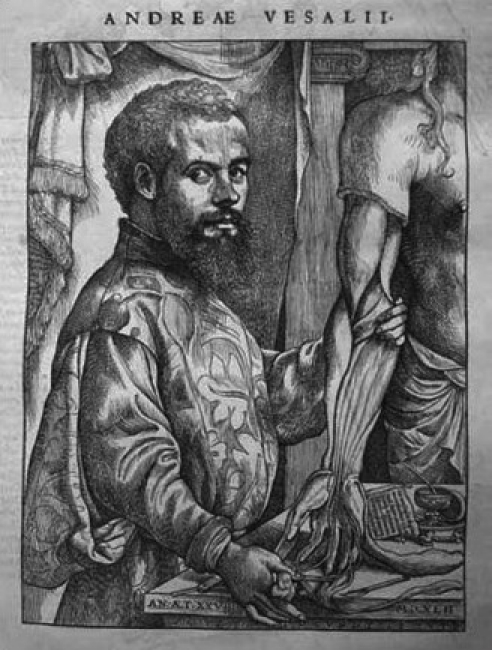

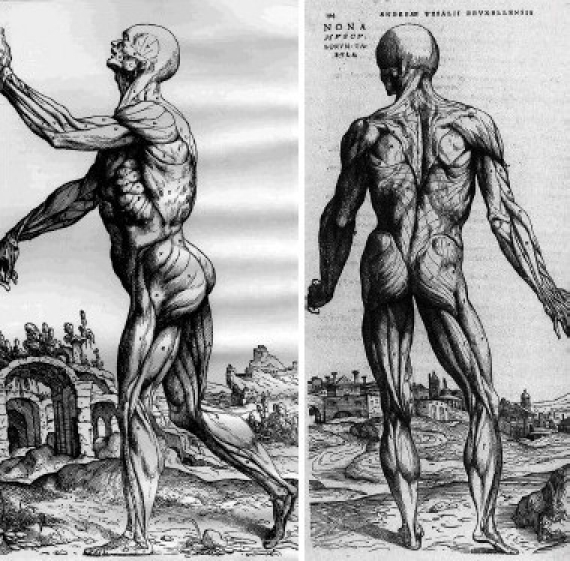

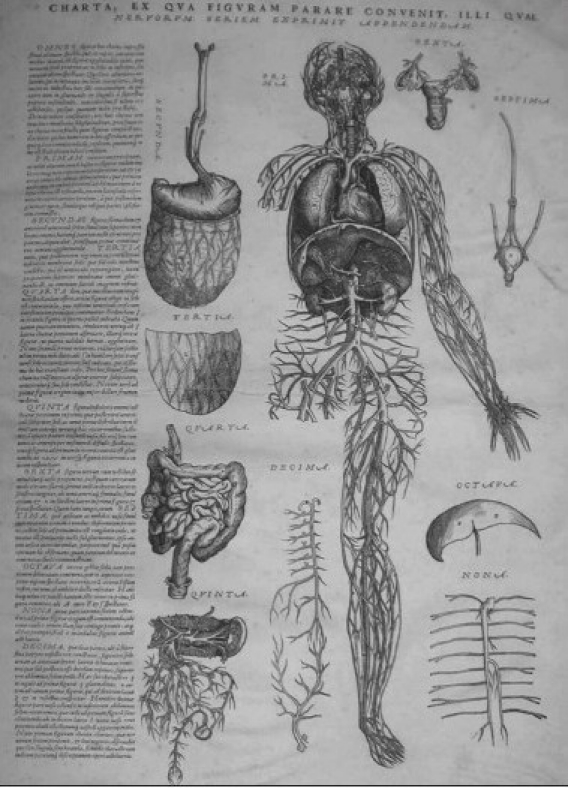

Anatomical illustration from De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius

Illustration showing the cardiovascular system from De Humani Corporis Fabrica by Andreas Vesalius

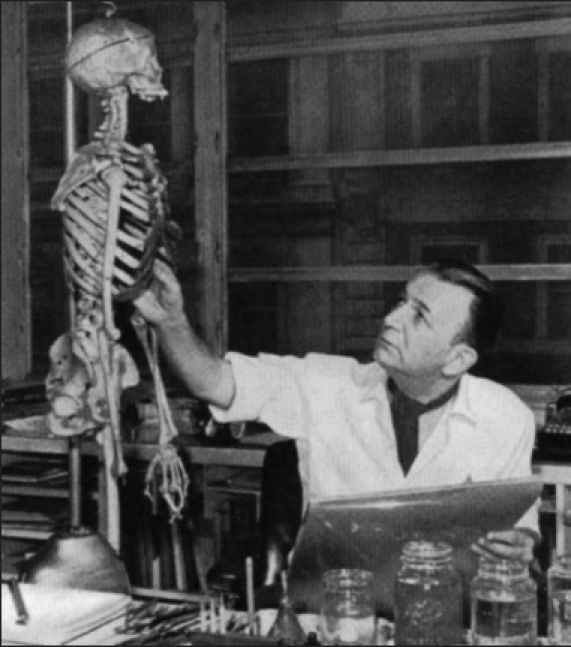

Frank Netter, M.D. “Medical Michelangelo.” Dr. Netter produced exquisite paintings of human anatomy, physiology, and pathology as well as illustrations of groundbreaking discoveries in medicine. (Photo Source: Netter FH.. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations. Volume 5)

Of course, it is not necessary for an artist to have performed dissections to render a realistic depiction of the human body but they have to have seen the human body, hence the nude models. But knowledge of anatomy makes for a highly skilled depiction of the human form, and artists during the Renaissance knew its value. Therefore, it was not unusual for artists and physicians to collaborate in producing an artistic and scientific work. Artists were interested in the study of proportion; scientists were interested in visualizing the anatomical relationships of various organs as well as depicting their function to understand and promote a particular theory. The symbiotic artist/physician interaction was extremely useful in advancing art and science.

When the physician-scientists saw the artistic and real-life renditions of the human body, they understood the power of these drawings and paintings and realized how visual illustration of systems clarified functions. Thus, during the Renaissance, physician-scientists were able to make a flood of new discoveries and inventions, and advance medical knowledge. Drawings, paintings, and sketches helped to better show and explain a medical finding.

Andreas Vesalius: De Humani Corporis Fabrica

“Anatomy is the foundation of medicine and should be based on the form of the human body” declared Hippocrates. The first complete and systematic description of the human body produced in Europe was De Humani Corporis Fabrica, a 16th century book authored by Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564), a Belgian anatomist and physician whose dissections of the human body helped correct many anatomical misconceptions dating from ancient times. During his time, surgery and anatomy were not considered important compared to other branches of medicine. Vesalius believed that surgery had to be grounded in anatomy. He performed many dissections and realized that many of Galen's ideas were wrong. He showed how anatomical dissection could be used to test speculation and underlined the importance of understanding the structure of the body in medicine.

Vesalius was lucky in his anatomical dissections because a Paduan judge who was interested in his work made bodies of executed criminals available to him so that he was able to make repeated and comparative dissections of humans. Through his dissections, Vesalius realized that many of Galen's anatomical descriptions were incorrect because Galen extrapolated his animal dissection findings to humans. After all, humans are not apes.

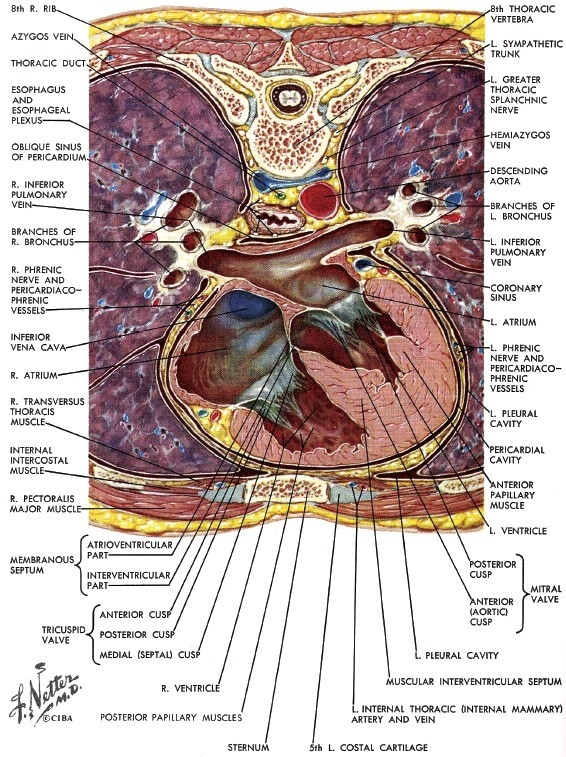

View of the thoracic cage as drawn by Dr. Netter. (Photo Source: Netter FH. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations. Volume 5)

When Vesalius published his book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) in 1543, he had already performed numerous dissections. The book contained 670 pages of texts and 186 anatomical plates of the human body, which were accurate in their observation and artistically superb. Vesalius commissioned a student of Titan (the famous Venetian master artist), and other artists to create the illustrations in his book. Vesalius worked with these artists, providing them with sketches of his dissections and guiding their drawings so that they would be accurate as well as appealing to the taste of Renaissance people. De Fabrica contained intricately detailed drawings of the human anatomy and became the standard anatomy book in Europe for centuries. Today, images from his book are still being used to inspire and instruct art students in the challenging task of drawing not only the human form but also the skeleton and muscles beneath the skin. The anatomical illustrations in the book are truly outstanding in their skill of execution and artistry.

Frank Netter, M.D.: “Medicine's Michelangelo”

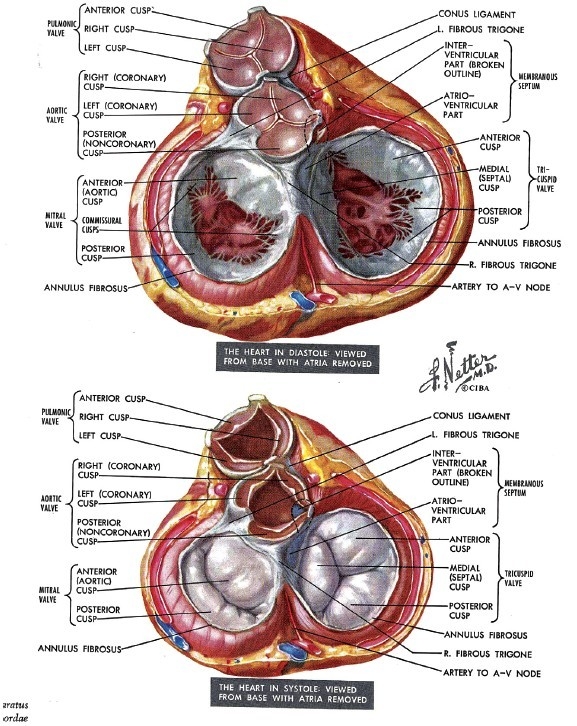

I am certain that many physicians are familiar with the work of Dr. Frank Netter (1906 – 1991), the surgeon-artist. He illustrated the major organs and their pathology for CIBA Pharmaceutical who then published them in a book. Dr. Netter produced exquisite paintings of human anatomy, physiology, and pathology as well as illustrations of groundbreaking discoveries in medicine. Later, he illustrated a series of atlases, a group of volumes individually devoted to each organ system, which cover human anatomy, embryology, physiology, pathology, and pertinent clinical features of the diseases arising in each system. Once seen, who can forget his atlases? In 1986, The New York Times dubbed him “The Medical Michelangelo.” Dr. Netter died in 1991 but his work lives on in books and electronic products that continue to educate millions of healthcare professionals worldwide.

Exquisite renditions of the cardiac valves in systole and diastole by Dr. Netter. (Source: Netter FH. The Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations. Volume 5)

The legacy of Max Brödel: Father of modern medical illustration

Max Brödel was a German artist who immigrated to the United States of America at the end of the 19th century. He went to Johns Hopkins and illustrated the works of Harvey Cushing, William Halsted, Howard Kelly, and other clinicians. His magnificent works are celebrated and is a well-known figure in surgical illustration. His work served an invaluable tool in educating students about anatomy, physiology and surgical procedures. His drawings have been reproduced in numerous textbooks, articles, and advertisements for over half a century.

Medical illustration is a highly difficult skill to master. Often the work is generated by an artist without medical training, or by doctors with limited artistic skills. Brödel worked hard to strike a balance between having sufficient medical knowledge and artistic skill. He revolutionized medical illustration. His important legacy is the establishment of the first school of medical illustrators at Johns Hopkins. His school was such a success that other medical illustration programs sprang up across the United States and Canada. Graduates of Brödel's school and the other schools would transform medical illustration into a profession so that medical illustrators nowadays have a master degree in medical illustration. The aim was to create professionals with an exceptional scientific background as well as being accomplished artists. Medical illustrators usually complete courses in anatomy and physiology, biology, art, chemistry, design, graphic art, computer illustration, and medical terminology.

Medical illustrators create many different types of graphic representations for a variety of purposes. They often create illustrations of human anatomy or surgical procedures for books and publications as well as produce animations and 3-dimensional models for seminars and lectures. Medical illustrators sometimes draw the steps taken during procedures and create illustrations of both healthy and diseased body parts to explain the effects of medical conditions. Some help create artificial body parts such as eyes. Medical illustrators often sketch by hand and use computer software to create their illustrations. Some specialize on specific area such as the heart or brain.

The use of art in medical education

“One might begin with philosophy but would end with medicine; or start with medicine and find oneself in philosophy”, so Aristotle pointed out in the 4th century B.C. I suppose we might say, “one might begin with art but would end with medicine; or start with medicine and find oneself in art.” Medicine and art, science and beauty: both seem to meet in the human body. Medicine seeks to reveal the mechanisms of the human body while art uses the human form to represent ideals of beauty in drawings and paintings. These two fields of human endeavor – medicine and art – are combined in the art of the medical illustrator.

There is no doubt that illustration in a medical text aids in the learning process. Although in medieval times, many medical manuscripts were illuminated, notably the Arabic scholarly treatises, the illustrations representing various anatomical systems, pathologies, or treatment methodologies reflect early reliance on classical scholarship, especially Galen, and hence, were unreliable. In addition, representations of internal organs were often fanciful. Andreas Vesalius's book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, was a landmark textbook in the history of medicine and art. Besides its value in teaching anatomy, it underlined the close collaboration between art and science and how each inspires the other to new heights.

Vesalius commissioned artists to do the detailed anatomic drawings in his book. The medical illustrator is an artist who explains medical concepts through art. Illustrating a medical concept is difficult and can be tricky. The medical illustrator must draw or paint the human body with scientific precision and at the same time brings artistic creativity to his work. In addition, he must possess problem solving skills as well as the spatial awareness of an architect. The medium through which he works consists of traditional pen and ink drawings and use of computer software. Today, animated computer based art is synergistically used with medical illustration to educate students about anatomy.

New advances in imaging technology are powerful tools to show pathology but illustration remains a cornerstone for selectively communicating disease processes. A drawing can highlight the important features of a structure for teaching and discussion purposes. A graphic representation of any medical subject is a very effective tool in communicating medical knowledge. Medical students depend on illustration to learn anatomical facts and details that maybe too subtle for the written or spoken word. Oftentimes, an illustration transmits the pertinent, useful, and important information much more effectively than words. They “tell a story” through their drawings. For surgical disciplines especially, students rely on tools such as 2-dimensional illustrations and 3-dimensional models to learn important concepts. The use of illustration is an integral aspect in teaching, learning, and communication with colleagues as it can highlight details not obvious in a photograph.

Nowadays, modern anatomical illustrations are based on our understanding of the body through modern imaging techniques rather than on studying cadavers. Much pathology previously only seen at autopsy is now picked up by modern imaging techniques while the patient is still living. In cardiology for instance, the echocardiographer and cardiac surgeon communicate through imaging and illustration. Traditional illustration and computerized images mutually aid one another in medical education. For example, video-assisted surgery seems to be synergistically working with traditional illustration to enhance the surgical learning experience for students.

Art has always helped solve communication dilemmas in medical education. There will always be a need to illustrate medical concepts as long as there are doctors and students eager to learn the intricacies of the human body and its complex functions. Visualization is the key to understanding; hence visual aids are fundamental to the learning process. Advances in computer graphics and imaging are generating vast new opportunities for creating and producing such visual aids. Subcellular processes too small to be seen even by the most advanced microscopes can come alive through computer animations. The Internet and wireless technology enables information to be widely and readily available to everybody. As medical and scientific information exponentially expands, as the methods of visual creation continue to grow and evolve, and as the ways in which information is distributed to doctors, patients and the public proliferate, medical illustration takes those concepts and methods – both the simple and the complex – and brings them to life.

REFERENCES

- 1.The history of pictograms. http://www.brocketthorne.com/iWeb/gclone/links_files/pictograms.pdf .

- 2.Lyons AS, Petrucelli RJ. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc; 1987. Medicine: An Illustrated History. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajar R. The pulse in antiquity. Heart Views. 1999;1:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajar R. Past Glories: The Great Library of Alexandria. Heart Views. 2000;1:278–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajar R. Body, Mind, and Medicine: Heart Views. 2000;1:412–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammed W. Ibn Rushd. Kulliyat Fi Tib (General Medicine) Al Hia’ Al Masria Al A’imah Lilkitab. :72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Abbadi M. Paris: Unesco; 1992. Life and fate of the ancient library of Alexandria; pp. 118–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Megill M. Galen and Circulation. Available from: http://ablemedia.com/ctcweb/showcase/megill5.html .

- 9.Hajar R. Da Vinci's Anattomical Drawings: The heart. Heart Views. 2002;3:100–1. [Google Scholar]