Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common form of localized, nonscarring hair loss. It is characterized by the loss of hair in patches, total loss of scalp hair (alopecia totalis, AT), or total loss of body hair (alopecia universalis, AU). The cause of AA is unknown, although most evidence supports the hypothesis that AA is a T-cell-mediated autoimmune disease of the hair follicle and that cytokines play an important role.

Aims:

The aim of the study was to compare the serum levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in patients with AA and the healthy subjects and also to investigate the difference between the localized form of the disease with the extensive forms like AT and AU.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty patients with AA and 20 healthy controls were enrolled in the study. Forty-six patients had localized AA (LAA), and 14 patients had AT, AU, or AT/AU. The serum levels of TNF-α were measured using enzyme-linked immunoassay techniques.

Results:

Serum levels of TNF-α were significantly higher in AA patients than in controls (10.31 ± 1.20 pg ml vs 9.59 ± 0.75 pg/ml, respectively). There was no significant difference in serum levels of TNF-α between patients with LAA and those with extensive forms of the disease.

Conclusion:

Our findings support the evidence that elevation of serum TNF-α is associated with AA. The exact role of serum TNF-α in AA should be additionally investigated in future studies.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, immunoassay, tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is common cause of reversible hair loss afflicting approximately 1 to 2% of the general population.[1] A wide range of clinical presentations can occur, from a single patch of hair loss to complete loss of hair on the scalp (alopecia totalis, AT) or over the entire body (alopecia universalis, AU). The cause of AA is unknown, although there is evidence to suggest that the link between lymphocytic infiltration of the follicle and the disruption of the hair follicle cycle in AA may be provided by a combination of factors, including cytokine release, cytotoxic T-cell activity, and apoptosis.[2] It is also considered that a disequilibrium in the production of cytokines, with a relative excess of proinflammatory and Th1 types, vs. anti-inflammatory cytokines may be involved in the persistence of AA lesions, as shown in human scalp biopsies.[3] Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic inflammatory disorders with an autoimmune component. This cytokine is synthesized in epidermal keratinocytes along with several other cytokines and is known to be a very potent inhibitor of proliferation.[4] The changes in serum TNF-α levels were found in many diseases, such as psoriasis[5,6] and systemic lupus erythematosus.[7] In some of these diseases, serum TNF-α concentration correlated with activity and intensity of the disease, and may be used as a prognostic factor.

Although it is well known that multiple cytokines simultaneously play role in AA, many authors have measured only one particular cytokine. Our study has focused only on TNF-α because there are only a few studies that have measured the serum levels of this cytokine with controversial results. Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate serum levels of TNF-α in AA patients and control subjects, and also to assess the difference between the localized and extensive forms of the disease such as AT and AU.

Materials and Methods

The study included 60 patients with AA (36 females and 24 males; median age, 35.6 years). Forty-six patients had localized AA (LAA) and 14 patients had AT, AU, or AT/AU. The patients were characterized according to AA investigational assessment guidelines.[8] The patients who had received any treatment within previous 3 months were excluded from the study, as well as patients with any diseases based on the immune pathomechanism, which could influence serum concentrations of TNF-α.

Control group consisted of 20 generally healthy subjects (11 females and 9 males; median age, 32.6 years).

Serum levels of TNF-α were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique, using Quantikine Human TNF-α Immunoassay (R and D System, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, a monoclonal antibody specific for TNF-α has been precoated onto a microplate. Standards and samples are pipetted into the wells and any TNF-α present is bound by the immobilized antibody. After washing away any unbound substances, an enzyme-linked polyclonal antibody specific for TNF-α is added to the wells. Following a wash to remove any unbound antibody-enzyme reagent, a substrate solution is added to the wells and color develops in proportion to the amount of TNF-α bound in the initial step. The color development is stopped and the intensity of the color is measured.

The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The test distribution was done by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and comparisons were performed by t-test. The data were considered statistically significant if P values were less than 0.05.

Results

The study group comprised of 60 (36 females and 24 males; the mean age was 35.6 years, ranging from 5 to 69 years) patients with AA and 20 healthy controls (11 females and 9 males; the mean age 32.6 years, ranging from 6 to 63 years). There were no significant difference in age and female/male ratio between the patients and controls (P >0.05). The mean duration of AA was 14.5 ± 25.4 (range, 1-119 months). In the total of patients with AA, 46 of them were LAA and 14 were AT, AU, or AT/AU group.

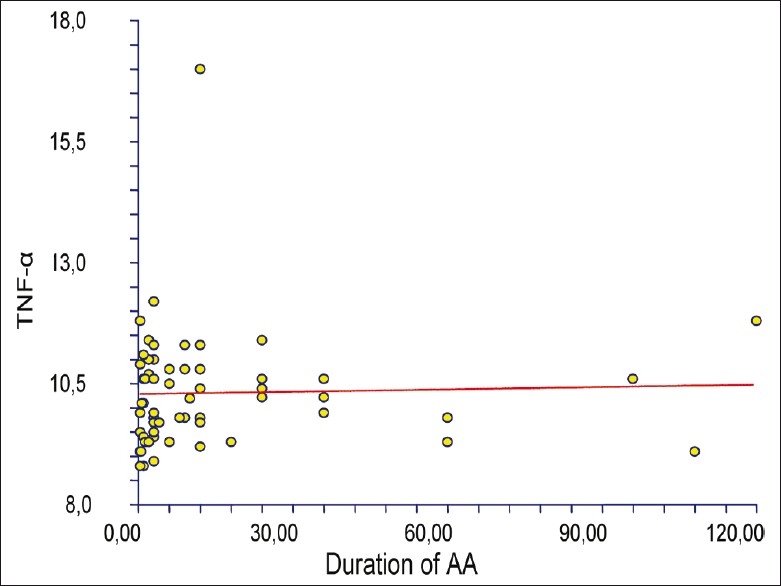

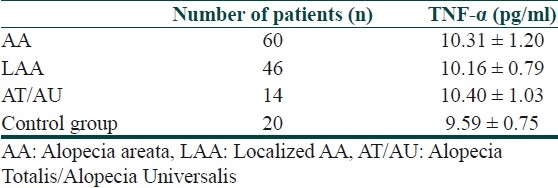

Serum TNF-α levels ranged from 8.8 to 17.0 pg/ml, with the highest values observed in the AU patients. The mean serum TNF-α in AA patients was 10.31 ± 1.20 pg/ml (mean ± SD), whereas that of LAA or extensive (AT, AU, or AT/AU) was 10.16 ± 0.79 pg/ml or 10.40 ± 1.03 pg/ml, respectively. Patients with longer duration of the disease had higher concentration of TNF-α, but not significantly [Figure 1]. The mean serum TNF-α level in controls was 9.59 ± 0.75 pg/ml. Table 1 presents some of the features of the study groups.

Figure 1.

Correlation between the duration of the AA and concentration of TNF-α,r = 0.034; ρ (rho) = 0.1142; 95% CI (-0,144; 0,358); P >0.05;-n.s

Table 1.

Serum concentrations (mean±SD) of TNF-α in patients with AA, LAA, AT/AU and in healthy controls

Serum levels of TNF-α in patients with AA were significantly higher than those in controls (P = 0.044). There was no significant difference in levels of TNF-α between patients with LAA and the extensive group (P=0.2272).

Discussion

Recent progress in the understanding of AA has shown that the regulation of local and systemic cytokines plays an important role in its pathogenesis. Hair loss may occur because proinflammatory cytokines interfere with the hair cycle, leading to premature arrest of hair cycling with cessation of hair growth.[9] This concept may explain typical clinical features of AA such as a progression pattern in centrifugal waves[10] and spontaneous hair regrowth in concentric rings,[11] suggesting the presence of soluble mediators within affected areas of the scalp.

TNF-α is a multifunctional proinflammatory cytokine which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many infections and inflammatory disorders. However, this cytokine not only acts as mediator of immunity and inflammation, but also affects not-immune responses within tissues such as cell proliferation and differentiation.[12] In vitro studies have shown that TNF-α, along with IL-1α and IL-β, causes vacuolation of matrix cells, abnormal keratinization of the follicle bulb and inner root sheath, as well as disruption of follicular melanocytes and the presence of melanin granules within the dermal papilla.[13] Experiments in cultured human hair follicles by Hoffmann et al. showed that TNF-α completely abrogated hair growth.[14] Additionally, TNF-α induced the formation of a club-like hair follicle, similar to catagen morphology of the hair bulb. A study by Thein et al. examined cytokine profiles of infiltrating activated T-cells from the margin of involved AA lesions.[15] It was found that T-cell clones from involved lesions inhibited the proliferation of neonatal keratinocytes. In examining the cytokine profiles and relating them to regulatory capacity, the authors found that T-cell clones that released high amounts of IFN-γ and/or TNF-α inhibited keratinocyte growth.

A limited number of studies in the literature have evaluated the serum levels of TNF-α in patients with AA. The results presented in our study demonstrate that the mean serum levels of TNF-α were significantly elevated in AA patients in comparison with healthy subjects. There was no significant difference in levels of TNF-α between patients with LAA and the extensive group. In contrast to our results, Teraki et al. reported that serum levels of TNF-α in patients with LAA were significantly higher than those in patients with AU.[16] In the study of Koubanova and Gadjlgoroeva, serum levels of TNF-α in patients with AA did not differ from that in controls.[17] However, TNF-α was lower in patients with severe form of AA than in patients with mild form. They hypothesized that similar levels of TNF-α in patients with both forms of AA and controls may indirectly indicate the absence of systemic immunopathological reactions in patients with AA, and the lowering of TNF-α level in the mild form may indicate the tendency to formation of immunodeficiency in patients with severe AA. In addition, Lis et al. found that serum levels of sTNF-α receptor type I were significantly elevated in patients with AA in comparison with healthy subjects.[18] As they conclude, these results indicate that immune mechanisms in AA are characterized by activation of T-cells and other cells, possibly keratinocytes.

Conclusion

TNF-α seems to be a useful indicator of the activity of AA and that it may play an important role in the development of this disease. Further investigations are required to clarify the pathogenic role and clinical significance of TNF-α and these findings may provide important clues to assist in the development of new therapeutic strategies for patients with AA.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, Moshell AN, Melton IJ. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted Country, Minesota, 1975-1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628–33. doi: 10.4065/70.7.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexis AF, Dudda-Subramanya R, Sinha A. Alopecia areata: Autoimmune basis of hair loss. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:364–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodemer C, Peuchmaur M, Fraitag S, Chatenoud L, Brousse N, De Prost Y. Role of cytotoxic T cells in chronic alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:112–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symington FW. Lymphotoxin, tumor necrosis factor, and gamma interferon are cytostatic for normal human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;92:798–805. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12696816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roussaki-Schulze AV, Kouskoukis C, Petinaki E, Klimi E, Zafiriou E, Galanos A, et al. Evaluation of cytokine serum levels in patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Int J Pharmacol Res. 2005;25:169–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;5:273–9. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez D, Correa PA, Gomez LM, Cadena J, Molina JF, Anaya JM. Th1/Th2 cytokines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Is tumor necrosis factor alpha ptotective? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;33:404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen E, Hordinsky M, McDonald-Hull S, Price V, Roberts J, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:242–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areta. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckert J, Church RE, Ebling FJ. The pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:203–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1968.tb11960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Rio E. Targetoid hair regrowth in alopecia areata: The wave theory. Arch Derm. 1998;134:142. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whicher JT, Evans SW. Cytokines in disease. Clin Chem. 1990;36:1269–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, Kealey T. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumor necrosis factor-á in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1996.d01-1099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann R, Eicheler W, Huth A, Wenzel E, Happle R. Cytokines and growth factors influence hair growth in vitro: Possible implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996;288:153–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02505825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thein C, Strange P, Hansen ER, Baadsgaard O. Lesional alopecia areata T lymphocytes downregulate epithelial cell proliferation. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:384–8. doi: 10.1007/s004030050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teraki Y, Imanishi K, Shiohara T. Cytokines in alopecia areata: Contrasting cytokine profiles in localized form and extensive form (alopecia universalis) Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1996;76:421–3. doi: 10.2340/0001555576421423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koubanova A, Gadjlgoroeva A. EHRS Brussels, Conference abstracts. 2002. Jul 27, 29, On the problem of pathogenetic heterogeneity of alopecia areata; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lis A, Pierzchala E, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. The role of cell-mediated immune response in pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Wiad Lek. 2001;54:159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]