Abstract

Background:

The association between psoriasis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease remains largely unelucidated in the Indian population.

Aims:

To study the prevalence of diabetes, insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis.

Materials and Methods:

Seventy-seven patients of chronic plaque psoriasis and ninety two age- and sex-matched controls were enrolled in the study over a period of one year. Clinical and biometric data were noted and fasting venous blood samples were collected. Nondiabetic patients were subjected to an oral glucose tolerance test with 75 g glucose and postprandial venous blood samples collected at 120 mins. The fasting glucose, insulin, lipid levels, postprandial glucose and postprandial insulin levels were measured in samples from nondiabetic patients whereas fasting lipid levels only were measured in diabetic patients.

Results:

The prevalence of impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes mellitus in psoriatics was 5.2%, 9.1%, and 32.5%, respectively, as compared to 6.5%, 3.3%, and 15.2%, respectively, in the controls. The difference was statistically significant. The odds ratio of having an abnormal glucose metabolism in psoriasis was 2.63. Smoking had a positive association with insulin resistance in psoriatic cases. The serum cholesterol levels were elevated in 29 (37.7%) cases with a mean of 186.27 ± 43.18 and 34 (37%) controls with a mean of 194.38 ± 57.20. The serum HDL-cholesterol levels were reduced in 50 (64.9%) cases with a mean of 53.29 ± 15.90 as compared to 71 (74.7%) in controls with a mean of 48.76 ± 12.85. The serum LDL-cholesterol levels were elevated in 38 (49.4%) cases with a mean of 102.56 ± 44.02 and 36 controls with a mean of 115.62 ± 54.37. The serum triglyceride levels were elevated in 25 (32.5%) cases with a mean of 129.99 ± 61.32 and 38 (41.3%) controls with a mean of 141.04 ± 80.10. The differences between the two groups were not statistically significant. The two groups did not differ with respect to other cardiovascular risk factors such as increased body mass index, increased waist size, increased waist-to-hip ratio, and hypertension.

Conclusion:

There is a positive association between insulin resistance and psoriasis. No association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia has been found in this study.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the skin and occasionally the joints. It causes significant physical and psychological morbidity to the patient, and is a considerable economic burden to both the patient and the health care system, largely associated with medication costs and frequent outpatient visits. Traditionally viewed as an inflammatory skin disorder of unknown etiology, recent advances in the understanding of immunopathogenesis and genetics of the disease have shifted the focus from a single organ disease confined to skin structures to a systemic inflammatory condition analogous to other inflammatory immune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

There is evidence for an inflammatory basis for diseases such as diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome that has stimulated research in examining the risk of these conditions in patients with systemic inflammatory disorders such as psoriasis. Should an excess risk of the above conditions be present among patients with psoriasis, this would represent an important unrecognized cause of morbidity and mortality.

Our aim was to study the prevalence of diabetes, insulin resistance, lipid abnormalities, and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with plaque psoriasis.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Topiwala National Medical College and B.Y.L. Nair Charitable Hospital, Mumbai, between August 2007 and September 2008 after being approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. It was a case-control, observational, cross-sectional study on patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The study group included 77 patients of chronic plaque psoriasis above 18 years of age attending the dermatology department. Ninety-two age- and sex-matched nonpsoriatic patients, attending the dermatology out-patient department were included as controls. Informed consent from all patients and controls was obtained prior to the study. Patients with guttate, pustular and unstable psoriasis, skin disorders with a systemic inflammatory component, e.g., immunobullous disorders, and autoimmune connective diseases were excluded from the study. All patients were observed by a dermatologist and a complete history was taken including duration of disease, course of disease, treatment history, concomitant illnesses, personal habits such as smoking, alcohol, tobacco consumption, family history of psoriasis, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. All patients were thoroughly examined and the extent and severity of disease was calculated by the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score, presence of nail, or joint involvement noted. Biometric data such as weight, height, waist, and hip circumference were noted. To determine waist circumference, a measuring tape was placed at the level of the umbilicus and the widest part of the hip for hip circumference. Blood pressure was recorded after subjects had been sitting for 5 min.

Venous samples were taken at the enrolment visit after the subjects after 12 h fasting overnight. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed using 75 g of glucose in nondiabetic patients and postprandial venous samples collected at 120 mins. The fasting glucose, fasting insulin, fasting lipid (cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, and triglycerides) levels, postprandial glucose, and postprandial insulin levels were measured in samples from nondiabetic patients whereas fasting lipid levels only were measured in diabetic patients.

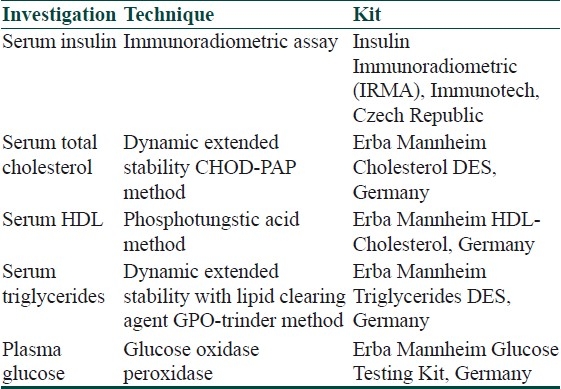

The following kits were used for the various biochemical tests [Table 1]:

Table 1.

Biochemical tests and kits used

The serum LDL was calculated by the formula “Total cholesterol - HDL–30” (Adult Treatment Panel III of the National Cholesterol Education Program).[1]

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria for diagnosis and classification of diabetes were used to categorize the results of OGTT as follows.

Normal glucose homeostasis (NGH) – fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of less than 100 mg/dL and 2-h OGTT result of less than 140 mg/dL after a 75-g oral glucose load.

Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) – fasting plasma glucose level of 100 mg/dL or greater but less than 126 mg/dL.

Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) – 2-h OGTT result of 140 mg/dL or greater but less than 200 mg/dL.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) – FPG level of 126 mg/dL or greater and a casual plasma glucose level of 200 mg/dL or greater.[2]

Insulin resistance in those with normal glucose homeostasis was evaluated using the following criteria.

Homeostasis model for assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR): blood glucose (fasting)/18 X Insulin (fasting) /22.5. Values ≥ 4 suggest insulin resistance.

Fasting glucose to insulin ratio ≤ 4.5.

Fasting serum levels of insulin > 30 μU/ml.

Body mass index or BMI (Quetelet's index) was calculated using the formula:

Weight (kg) /[Height (m)].[2]

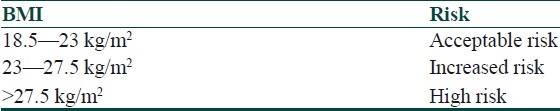

WHO expert consultation on risk of cardiovascular diseases based on recommended BMI in Asian populations are given below [Table 2].

Table 2.

WHO expert consultation on risk of cardiovascular diseases based on recommended BMI in Asian populations

Waist-to-hip ratios greater than 0.95 in men and greater than 0.8 in women are the thresholds for significantly increased potential cardiovascular risk. It was proposed that cut-off values for waist circumference for Indian men and women be 85 cm and 80 cm, respectively.[5,6]

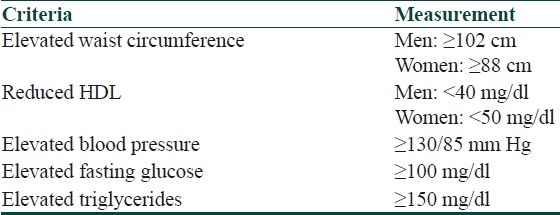

Criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program's Adult Panel III (ATP III) for diagnosis of metabolic syndrome have been given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Criteria of the national cholesterol education program's adult panel III (ATP III) for diagnosis of metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome can be identified by presence of three or more of the above criteria.[1]

The National Cholesterol Education Program Blood Lipid guidelines for optimal blood lipid levels:

Total cholesterol <200 mg/dl

HDL-cholesterol >60 mg/dl

LDL-cholesterol <100 mg/dl

Triglycerides <150 mg/dl.[1]

Following tests were applied for statistical analysis.

Pearson's chi-square (with continuity correction where applicable) test for nominal data.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and Tukey HSD tests for comparison between multiple variables within the study and control groups.

Unpaired t-test to compare numerical variables.

Values were reported as the mean ± SD; statistical significance was attributed to two-tailed P<0.05.

Results

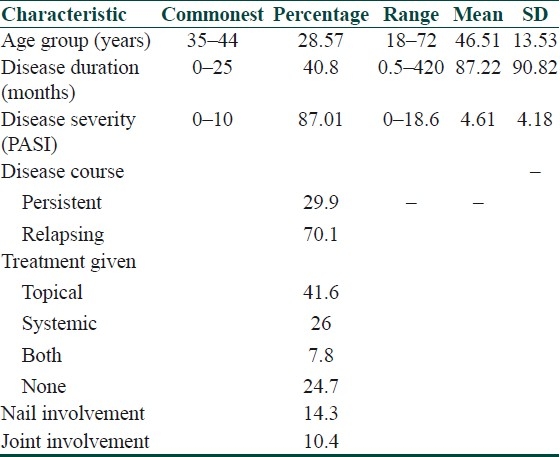

The commonest age group was 35–44 (n=22, 28.57%) followed by 55–64 (n=21, 27.27%). The mean age in the control group was 43.24 ± 12.33. The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to age (Student's t-test; t=1.641, P=0.105). The disease duration ranged from a low of 15 days to a maximum of 35 years. Thirty-one (40.8%) patients had disease duration of 25 months or less with a mean duration of 87.22 months. Sixty-seven (87.01%) patients had a PASI score of less than ten, i.e., mild disease. Fifty-four (70%) patients had a relapsing course of psoriasis. Thirty-two (41.6%) patients were on topical therapy, mainly topical glucocorticoids. Twenty (26%) patients were on systemic therapy, i.e., oral methotrexate. Nail involvement was seen in 11 (14.3%) cases and joint involvement in 8 (10.4%) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Characteristics of the study group (n=77)

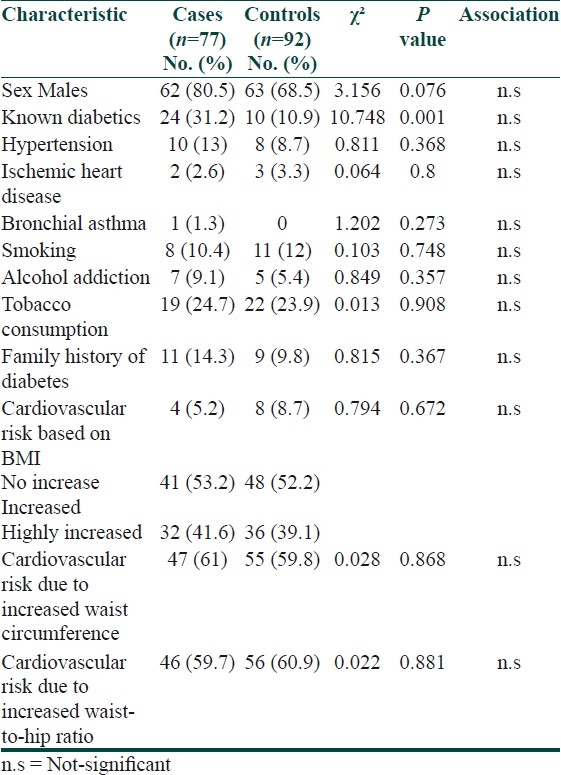

Diabetes was significantly more common in cases than in controls (P=0.001). The two groups did not differ with regard to medical illnesses such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and bronchial asthma; substance addiction such as smoking, alcohol, and tobacco consumption, family history of diabetes. Although majority of the patients showed an increased risk of cardiovascular disease based on BMI, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio, it did not differ between the two groups [Table 5].

Table 5.

Clinical profiles of both groups

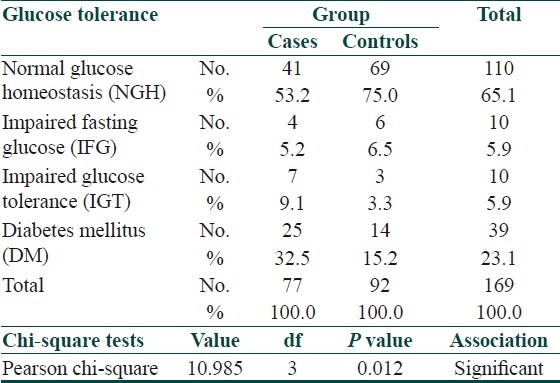

In addition to those who were known diabetics, one in the case group and four in the controls were diagnosed as having diabetes on OGTT. Thus, psoriatics had IFG, IGT, and DM rates of 5.2%, 9.1%, and 32.5%, respectively, as compared to 6.5%, 3.3%, and 15.2%, respectively, in the controls. The difference was statistically significant [Table 6].

Table 6.

Results of the OGTT

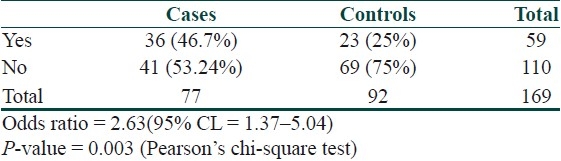

The odds ratio of having an abnormal glucose metabolism in psoriasis was 2.63 [Table 7].

Table 7.

Odds ratio of abnormal glucose metabolism in psoriasis

The fasting insulin levels, postprandial insulin levels, fasting glucose-to-insulin ratio, and HOMA-IR in those with normal glucose homeostasis on OGTT did not differ significantly between the two groups [Table 8].

Table 8.

Insulin sensitivity indices in those with normal glucose homeostasis

The insulin resistance in psoriatics did not appear to be related to the following variables.

Duration of disease [one-way ANOVA; F-value = 0.278, P=0.841]

Disease severity (PASI score) [one-way ANOVA; F-value = 0.757, P=0.522]

Treatment received [Pearson's Chi square value = 13.95 degree of freedom (df) = 9, P=0.124]

Presence of nail involvement [Pearson's Chi square value = 3.906 df = 3, P=0.272]

Presence of joint involvement [Pearson's Chi square value = 3.214 df = 3, P=0.360]

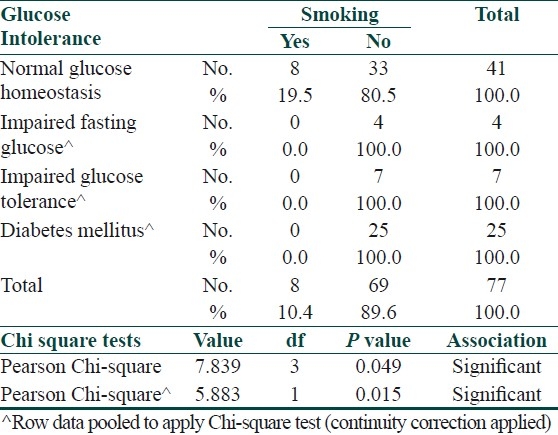

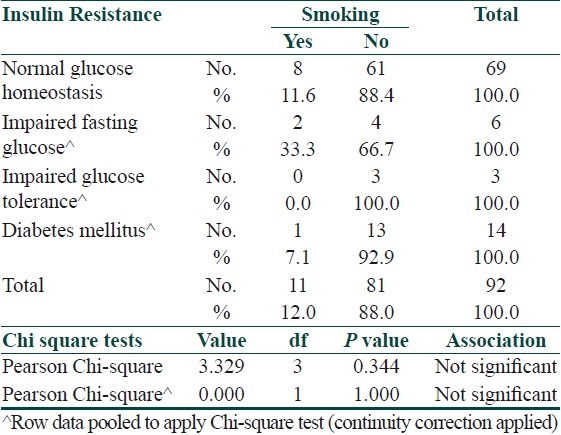

Smoking appeared to have a positive association with insulin resistance in cases however it did not do so in controls [Tables 9 and 10].

Table 9.

Association between insulin resistance and smoking in cases

Table 10.

Association between insulin resistance and smoking in controls

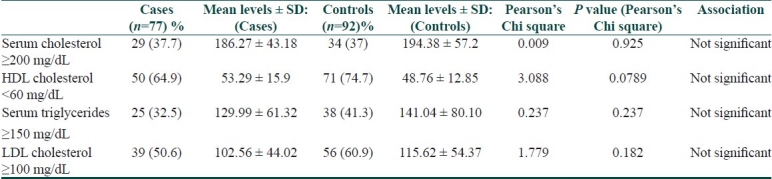

The mean LDL cholesterol levels were elevated and the mean HDL cholesterol levels were reduced in both groups; however, the differences were not significant. Interestingly, the mean cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides were lower in cases and the mean HDL higher as compared to controls, though not statistically significant [Table 11].

Table 11.

Comparison of lipid profiles between the two groups

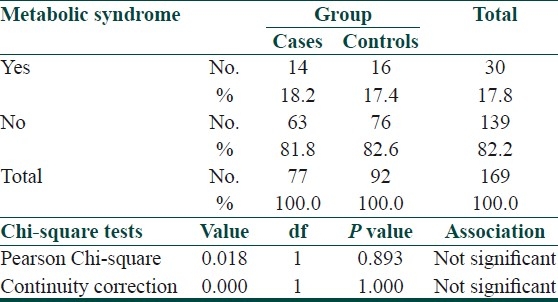

No significant association of metabolic syndrome was seen in patients of psoriasis as compared to controls [Table 12].

Table 12.

Association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome

Discussion

The occurrence of one or multiple disorder(s) in association with a given disease (comorbidity) has recently gained interest in various fields of medicine. Often comorbidity appears to be related to common pathogenetic pathways. In contrast to syndromes, which comprise symptoms that appear synchronously, comorbidities reflect timely unrelated secondary disease involving the same or additional organs. Comorbidities tend to arise in complex disorders, they are frequently multigenic and multifactorial, and most often demonstrate an inflammatory background. Such is the case with psoriasis.[7] Many studies undertaken in western populations highlight the association between psoriasis and diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemias, and cardiovascular disorders. As a race, Asian-Indians have a higher predisposition to obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders as compared to western populations.[8] There is a paucity of literature highlighting the association of psoriasis with diabetes, dyslipidemias, and cardiovascular disorders in Indian populations.

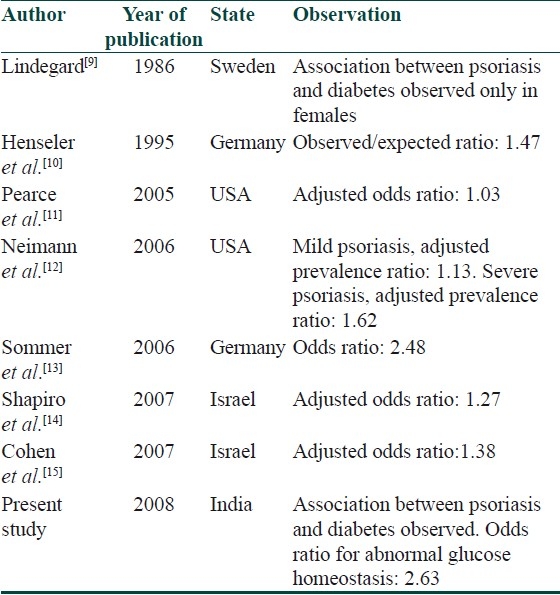

Psoriasis, insulin resistance and diabetes

In our study, we found a significant association between psoriasis, diabetes, and insulin resistance with an odds ratio of 2.63 of abnormal glucose homeostasis in psoriatics as compared to controls. No significant differences was found between the two groups with respect to HOMA-IR, fasting insulin-to-glucose ratio, fasting, and postprandial serum insulin levels in those with normal glucose homeostasis. Further studies will have to be carried out in larger number of patients with normal glucose homeostasis. Our study supports previous observations [Table 13].

Table 13.

Literature review of association of psoriasis and diabetes

In a similar case-control study of 110 patients, impaired glucose tolerance was seen in 18.6% psoriatics as compared to only 2.5% controls. Similar to our study, duration and severity of psoriasis had no effect on insulin resistance. The fasting insulin, HOMA-IR was significantly higher in psoriatics but the fasting insulin to glucose ratios did not differ significantly between cases and controls. Markers for insulin resistance were higher in older patients as compared to younger patients.[16]

Nigam et al., demonstrated abnormal glucose tolerance in 27.7% of 65 uncomplicated cases of psoriasis.[17] In a small study of 20 patients of psoriasis by Sundharam et al., 30% showed an abnormal glucose tolerance.[18]

The PASI score in our study ranged from 0 to 18.6, i.e., severity of psoriasis was mild in most of the patients. This might be an explanation why no correlation between severity and insulin resistance was found. Also, it is known that the PASI index score may not exactly reflect the severity and activity of the disease.[19]

A possible explanation for the association between psoriasis and diabetes is the presence of chronic inflammation that occurs due to persistent secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and other proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6, which precipitates both psoriasis and diabetes. Chronic systemic inflammation induces endothelial dysfunction, altered glucose metabolism, and insulin resistance that play a significant role in the development of obesity, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease.[15]

It is also possible that patients with psoriasis use topical corticosteroids for long periods, which are absorbed systemically and predispose the patients to diabetes.[20]

Psoriasis and dyslipidemias

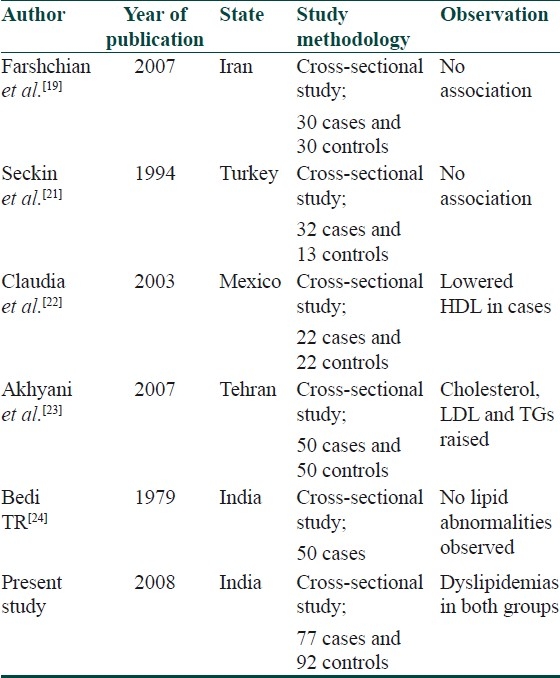

In our study, the mean LDL cholesterol was elevated and the mean HDL cholesterol was lowered in both groups; however, they were not significantly different. The results are similar to a case-control study in 60 patients which show no correlation between lipid profiles in patients with psoriasis as compared to matched controls.[19] Association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia has been conflicting and controversial [Table 14].

Table 14.

Literature review of association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia

Psoriasis and cardiovascular disease

The risk factors for cardiovascular disease did not differ between the two groups. Increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors were seen in both groups, namely increased BMI, increased waist circumference and increased waist-to-hip ratio. Diabetes mellitus, which is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease was significantly more common in psoriatics as compared to controls in our study. In a study by McDonald and Calabresi, the risk of arterial and venous vascular diseases (e.g., myocardial infarction, thrombophlebitis, pulmonary embolization, and cerebrovascular accident) was 2.2 times higher among the 323 patients with psoriasis compared with 325 control patients with other dermatologic conditions. Disease duration did not appear to have an effect on the risk, but extent of skin involvement was associated with a slightly higher risk in older age groups.[25]

Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors including dyslipidaemia, glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, central obesity, and hypertension, and is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and stroke. In a study by Gisondi et al., a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome was seen in psoriatic patients.[26] In our study no differences were found between the two groups with respect to metabolic syndrome. A high prevalence of metabolic syndrome is seen in Indians, and psoriasis could represent an additional source of morbidity due to its positive association with insulin resistance.[27]

Study Limitations

Selection bias – hospital-based controls were enrolled instead of general population.

Patients of psoriasis were on treatment like topical corticosteroids and oral methotrexate whereas the control group consisted of patients who were not on these medications. More studies are needed in untreated psoriasis patients or in those after a drug washout period.

Wide ranges of duration of psoriasis in this study and the mixture of early state and chronic disease could bias the estimates toward decreased differences between cases and controls.

Inability to evaluate additional risk factors for occlusive vascular disease and cardio-vascular events such as apolipoproteins.

Conclusion

This is the first comprehensive study in the Indian setting with age-, sex-, and BMI-matched cases and controls using contemporary biochemical investigative modalities.

A positive association between psoriasis and insulin resistance and diabetes has been observed. Smoking has shown to have a positive association with insulin resistance in psoriatics. Therefore, cutting back on smoking which is known to exacerbate psoriasis and cause cardiovascular disease may also help improve insulin resistance.

Our study did not show an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemias; however, an interesting observation was lower mean cholesterol, LDL, triglycerides and elevated mean HDL in cases as compared to controls.

Psoriasis was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular risk factors except diabetes mellitus as compared to controls.

On the other hand, an increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes is seen in Indians; therefore, treatments must be designed to encourage lifestyle alterations such as diet modifications and exercise in addition to pharmacotherapy for psoriasis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus: Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–97. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses A. Syndromes of extreme insulin resistance. In: Kahn RC, Weir GC, King Gl, Moses AC, Smith RJ, editors. Joslin's Diabetes mellitus. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lipincott, Williams and Wilkins Publishing; 2005. pp. 493–520. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legro RS, Finegood D, Dunaif A. A fasting glucose to insulin ratio is a useful measure of insulin sensitivity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2694–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO expert consultation. Appropriate body mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies concept. Lancet. 2004;363:157–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snehalatha C, Viswanathan V, Ramachandran A. Cut-off values for normal anthropometric variables in Asian Indian adults. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1380–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christophers E. Comorbidities in Psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mukhopadhyay B, Sattar N, Fisher M. Diabetes and cardiac disease in South Asians. [cited 2010 Jan 29];Br J Diab Vasc Dis. 2005 5:7. Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/518073 . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindegard B. Diseases associated with psoriasis in a general population of 159 200 middle-aged, urban, native Swedes. Dermatologica. 1986;172:298–304. doi: 10.1159/000249365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982–6. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearce DJ, Morrison AE, Higgins KB, Crane MM, Balkrishnan R, Fleischer AB, Jr, et al. The comorbid state of psoriasis patients in a university dermatology practice. J Dermatolog Treat. 2005;16:319–23. doi: 10.1080/09546630500335977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:829–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommer DM, Jenisch S, Suchan M, Christophers E, Weichenthal M. Increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298:321–8. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0703-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, Hodak E, Chodik G, Viner A, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: A case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Shapiro Y, Vidavsky L, Vardy DA, Davidovici B, et al. Psoriasis and diabetes: A population-based cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:585–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ucak S, Ekmekci TR, Basat O, Koslu A, Altuntas Y. Comparison of various insulin sensivity indices in psoriatic patients and their relationship with type of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:517–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nigam P, Dayal SG. Diabetic status in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1979;45:171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundharam A, Singh R, Agarwal PS. Psoriasis and diabetes mellitus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1980;46:158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farshchian M, Zamanian A, Farshchian M, Monsef AR, Mahjub H. Serum lipid level in Iranian patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:802–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, Belloni Fortina A, Peserico A, Virgili AR, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: Results from an Italian case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seçkin D, Tokgözoğlu L, Akkaya S. Are lipoprotein profile and lipoprotein (a) levels altered in men with psoriasis? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:445–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynoso-von Drateln C, Martínez-Abundis E, Balcázar-Muñoz BR, Bustos-Saldaña R, González-Ortiz M. Lipid profile, insulin secretion, and insulin sensitivity in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:882–5. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akhyani M, Ehsani AH, Robati RM, Robati AM. The lipid profile in psoriasis: A controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1330–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedi TR. Blood sugar and serum cholesterol levels in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1979;45:272–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald CJ, Calabresi P. Psoriasis and occlusive vascular disease. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:469–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisondi P, Tessari G, Conti A, Piaserico S, Schianchi S, Peserico A, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: A hospital-based case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Satyavani K, Sivasankari S, Vijay V. Metabolic syndrome in urban Asian Indian adults: A population study using modified ATP III criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;60:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(03)00060-3. Original Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]