Abstract

Background:

There exists a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in dermatological patients. Although, investigators have evaluated psychiatric aspects of the patients suffering from skin diseases; there are rare studies concerning mental health in pemphigus patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate mental health status and quality of life of newly diagnosed pemphigus patients.

Materials and Methods:

Between April 2007 and June 2008, all newly diagnosed pemphigus patients attending the outpatient clinic of a dermatological hospital were given a questionnaire comprising the GHQ-28 and DLQI to fill out.

Results:

Of 283 patients, 212 complete forms were returned. The bimodal score of GHQ ranged from 0 to 26 (Mean = 9.4) and the Likert score of GHQ ranged from 6 to 68 (Mean = 31.9). The DLQI score ranged between 0 and 30 (Mean of 13.8). A total of 157 patients (73.7%) were yielded to be possible cases of mental disorder considering GHQ-28 bimodal scores. Significant correlation was detected between the DLQI score and bimodal and Likert scoring of GHQ-28.

Conclusion:

Our study has depicted high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity in pemphigus patients. It underlines the fact that physicians, who are in-charge of care for these patients, are in an exceptional position to distinguish the psychiatric comorbidity and to take appropriate measures.

Keywords: DLQI, GHQ-28, pemphigus, psychiatric comorbidity

Introduction

Skin diseases are very common in the community and a large number of general practice visits are due to dermatological problems.[1,2] Most dermatologists believe that psychiatric problems are frequent among subjects coming to their attention and several studies on dermatological patients have revealed that they prevalently suffered from psychiatric disorders.[3,4] The presence of a chronic condition is normally associated with lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and disease severity also influences HRQOL.[5]

Besides any underlying mechanism relating psychiatric comorbidity and dermatological diseases, it is important to consider the consequence of the interrelation between these two. For instance, psychiatric comorbidity associated with increased subjective perception of pruritus,[6] is higher among patients whose skin condition does not get better with treatment,[7] and may affect treatment compliance.[8] However, so far, investigators have evaluated psychiatric aspects of the patients suffering from specific skin diseases such as psoriasis, acne, vitiligo, genital herpes, alopecia areata, hirsutism, and port-wine stains;[9–11] there are a few studies concerning mental health in pemphigus patients.

Pemphigus (from Greek pemphix meaning bubble) designates a set of life-threatening autoimmune blistering diseases characterized by intraepithelial blister formation.[12,13] Several forms of pemphigus have been described, including two major sub-types, pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Since pemphigus is a relapsing, difficult-to-treat illness requiring long-term hospitalization and immunosuppressive treatment besides affecting the patient's appearance, it may inflict significant psychological trauma to the patients. Pemphigus patients are prone to different psychiatric disorders such as profound depression and suicidal ideations.[14] Therefore, they should be carefully assessed for comorbid psychiatric disorders and be treated appropriately. Regarding the lack of evidence about mental health in pemphigus patients, it is necessary to evaluate their mental health status and its determinants.

The intent of this present study was to evaluate mental health status, HRQOL, and psychological well-being of newly diagnosed pemphigus patients. The information collected in our study may help to improve dermatologists’ view to pemphigus patients’ psychological aspects and finally to enhance patients’ well-being.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out between April 2007 and June 2008 at the outpatient pemphigus clinic of Razi Hospital, a well-equipped dermatological university hospital located in the center of Tehran. It is by far the largest dermatological hospital with the largest registry of pemphigus patients in Iran. Our study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The population included recently diagnosed pemphigus patients referred to the pemphigus clinic of the hospital. Literate patients who did not mention any prior treatments for the skin disease and did not have any record of documented psychiatric disorder were chosen and given the research questionnaires including an information letter and the consent form. A research assistant was present in the clinic's waiting area to offer further information and aid in answering the questionnaires. The questionnaires had a small section on socioeconomic variables, the Persian version of GHQ-28, and the Persian version of the 10-item DLQI.

GHQ is an extensively validated and highly reliable questionnaire initially developed by Goldberg and Hillier to screen for somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression. This questionnaire was translated into Persian (official language of Iran), which is understandable to almost every Iranian, and its validity and reliability approved in a previous study.[15]

DLQI is a general questionnaire to assess HRQOL in dermatological patients. It can be simply handed to the patient and completed in one to two minutes. The questions are categorized to 6 heading items: symptoms and feelings (questions 1 and 2), daily activities (questions 3 and 4), leisure (questions 5 and 6), and personal relationships (questions 8 and 9) each item with a maximum score of 6; and work and school (question 7), and treatment (question10) each item with a maximum score of 3. The DLQI score was calculated by summing the score of each question resulting in a maximum of 30 and a minimum of 0. The higher the score, the more quality of life is impaired.[16]

All subjects who signed the informed consent were instructed to fill out the questionnaires before the dermatological visit. After the visit, dermatologists registered the type, duration, location, and course of pemphigus. GHQ-28 scores were computed both in the conventional bimodal way, collapsing adjacent responses to get a dichotomous scoring (0-0-1-1), and in the Likert scoring method which assigns separate scores to each response category (0-1-2-3) to carry out correlation analysis.

Independent sample t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for comparing quantitative data between groups with normal distribution. Chi-square was used to test for differences in categorical variables.

Results

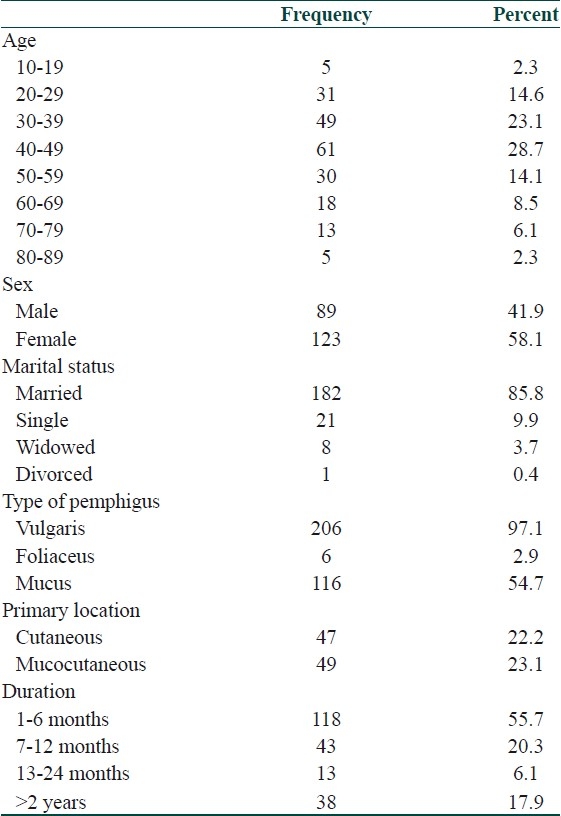

Of the 283 patients (aged 15 to 87 years mean ± SD, 44.9 ± 15.4) who signed the consent and were given the questionnaires, 271 returned them. Of the returned questionnaires, 58 were either blank or incomplete, which were excluded from further analyses. Finally, we had a total of 212 patients for the final analysis, leaving a response rate of 74.9%. Number of female and male participants were almost equal (female = 58.2% and male = 41.8%). Most of them were married (85.9%). Our patients mostly had pemphigus vulgaris (97.2%), and they mostly suffered from pure mucosal lesions (54%) followed by mucocutaneous (23%) and pure cutaneous (22%) lesions. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are all summarized in Table 1. A comparison between the patients who completed the questionnaires and those who did not give it back or returned it blank or incomplete confirmed no significant differences regarding sex, marital status, and educational background.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the patients

The bimodal score of GHQ ranged from 0 to 26 with a mean of 9.4 and the Likert score of GHQ ranged from 6 to 68 with a mean of 31.9. The DLQI score ranged between 0 and 30, with a mean of 13.8.

The best cut-off point for GHQ-28 bimodal score was determined to be 6 in a previous study in Iran, i.e., those scoring 6 and above were designated as possible cases of mental disorder. Sensitivity, specificity, and overall misclassification rate for a GHQ-28 cut-off score of 6 were 84.7%, 93.8%, and 8.2%, respectively.[15] In our study, a total of 157 patients of 212 scored ≥6 on GHQ-28 bimodal scoring, yielding a prevalence of 73.7% for possible cases of mental disorder (95% CI = 67.6-79.8%).

There were no significant correlations between bimodal or Likert score of GHQ and age or gender of the patients. We also could not find any significant correlations between the raw score of DLQI and gender, age, or duration of disease. The bivariant analysis of the data revealed a significant positive correlation between the DLQI score and bimodal and Likert scoring of GHQ with Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.466 and 0.477, respectively (P<0.001). There also was a significant relation between the patients’ mental health and the DLQI raw score shown by ANOVA (P<0.001). The mean score of DLQI was 12.8 among the patients with the first pemphigus presentation and 15.9 among those who suffered recurrent attacks. Thus, there was a significant correlation between the course of disease (first episode or recurrence) and raw score of DLQI. There could not be found any significant relation between the DLQI score and gender or age of the patients.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study has been the first one done to evaluate the psychiatric disorders in pemphigus patients. We had the response rate of 74.9%, which means 212 patients of 283 returned the questionnaires fully answered. It is really an acceptable rate. About 74% of the 212 patients that we studied were identified by the GHQ- 28 as having significant psychiatric comorbidity. This prevalence estimate should be considered reliable as the sample was quite large enough.

In our study, 157 patients of 212 scored ≥6 on GHQ- 28 bimodal scoring, yielding a prevalence of 73.7% for possible cases of mental disorder (95% CI = 67.6-79.8%). Therefore, the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity in pemphigus patients is shown to be three or four times higher compared with studies concerning psychiatric disorders in other dermatological outpatients.[17,18] Many reasons may explain the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders in pemphigus patients. First, psychiatric disorders may often come about as a complication or a result of a primary skin ailment, in reaction to disfigurement, supposed social stigma, or undesirable changes in life-style resulting from skin disease. As the deformity and disfigurement is worse in pemphigus and it is a chronic, difficult to treat disorder that has got a great impact on life style of the patients, more psychiatric disorders can be predictable.[3] Second, pemphigus patients are of older age which may cause possible psychiatric comorbidities. Dermatologists may encounter obsessive-compulsive disorder more commonly among pemphigus patients which may be either due to an autoimmune background of obsessive-compulsive disorder similar to that of the pemphigus or due to the strict abstinence that pemphigus patients should obey which may cause obsession. Finally, some drugs used in pemphigus patients, such as corticosteroids, may cause psychiatric symptoms.[3] Future studies should investigate in more detail the relative importance of these relationships between pemphigus disease and psychiatric comorbidities.

A well-known practical trouble in studying psychiatric comorbidity in the environment of physical illness is that symptoms of somatic disease, for example, reduced appetite, lack of energy, weight changes, autonomic dysfunction, or sleeplessness, may overlie with symptoms of psychiatric illness, consequently creating diagnostic difficulties. Nonetheless, this problem is much less grave with dermatological patients, as the symptoms of the immense majority of dermatological illnesses do not overlap with the somatic disturbances that may be found in psychiatric disorders.[7] In pemphigus patients, however, these constitutional disorders may be of huge importance. Our choice of the GHQ-28 largely avoids this problem as it contains only few items inquiring about somatic symptoms.[7] Probably, most of our GHQ-28 high scorers have a psychiatric condition, usually a depressive disorder or an anxiety disorder. Nonetheless, some GHQ- 28 high scorers may be experiencing considerable distress associated with their pemphigus disease, rather than having a formal psychiatric disorder.

Our findings are approximately consistent with the outcome of earlier studies of the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity in dermatological patients. These studies have been carried out in diverse geographical areas. Hughes et al.[3] studied 196 dermatological outpatients and 40 inpatients, and reported that 30% of outpatients and 60% of inpatients scored above the threshold score on the GHQ-30. Wessely and Lewis[19] studied 160 new attendees of adult age at a dermatology outpatient clinic. The prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity was evaluated both by a questionnaire and an interview, and was found to be 42.7% defining cases by the GHQ-12 and, similarly, 40.2% defining cases by the Clinical Interview Schedule. Johnson and Mostaghimi[4] studied 132 consecutive patients attending the dermatological clinic at the Port Moresby General Hospital in Papua New Guinea. Subjects were screened with the Harding Self Rating Questionnaire, and those scoring above a threshold were examined by a psychiatrist. A very high comorbidity between dermatological diseases and psychiatric disorders was reported, as 71.6% of the female patients and 69.2% of male patients were diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder according to International Classification of Diseases version 9 criteria, in most cases anxiety neurosis or neurotic depression. Aktan et al.[20] studied a sample of 256 outpatients in Turkey. The overall prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity was 41% defining cases by the GHQ-12 and 33.4% defining cases by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder SCID-I. Most identified cases were affected by a depressive disorder, an anxiety disorder or a somatoform disorder.

A significant finding in our study was the positive correlation between DLQI and GHQ-28, which means HRQOL, was probably impaired by psychiatric comorbidities in patients with pemphigus. Our observation revealed a strong relationship between psychiatric comorbidities and poorer HRQOL, both measured using standard self-administered questionnaires of established validity and reliability. This association was constant in a wide variety of skin conditions, representing a broad range of quality-of-life involvement and different clinical severity levels. The association between psychiatric comorbidities and poorer HRQOL did not rely on the severity of the skin condition. These results are of particular interest as they symbolize typical problems encountered by dermatologists in their daily practices. The importance of the differences in quality of life between patients with and those without psychiatric disorders was often outstanding, and has been observed in all domains of quality of life.

It should also be taken into consideration that the high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders in dermatological patients detected in this study, as well as in the mentioned studies, may partly be the result of a selection bias. Anxiety and depression may affect illness behavior of patients, for instance inducing an increment in help-seeking behavior such as frequently visiting a dermatological clinic. It should also be added that as we mainly relied on patient-rated measures, the issue of reporting bias should also be taken into account. It is probable that patients might have thought that the clinician who was about to see them would have access to the questionnaire results, and thus they may have tended to present themselves as more symptomatic and distressed in an attempt to engage the interest and sympathy of the clinician.

Regarding variables associated with the presence of a psychiatric disorder in dermatological patients, it should be emphasized that our study has a cross-sectional design that does not allow us to draw causal inferences. Therefore, the identification of a variable as a predictor does not imply that this variable plays an etiological role in promoting psychiatric disturbance.

We could also have made our study stronger if we had performed a full DSM-IV psychiatric interview with those assigned to have mental disorder according to GHQ-28. Of course, psychological or psychiatric treatment is not commonly and consistently helpful and not all patients with signs of emotional distress should be referred to a mental health professional. Future studies should be aimed at evaluating the benefits pemphigus patients can have by being referred to a psychiatrist.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by Psychiatric and Psychological Research Centre, as a joint project between Razi Dermatology Hospital and Roozbeh Psychiatry Hospital, both affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. We hereby would like to thank all the staff who contributed to this project in both hospital departments. We are also grateful to Dr. Nina Asghari and Dr. Deniz Ozdin for their kind company and comments.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Psychiatric and Psychological Research Centre, as a joint project between Razi Dermatology Hospital and Roozbeh Psychiatry Hospital

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rea JN, Newhouse ML, Halil T. Skin disease in Lambeth: A community study of prevalence and use of medical care. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1976;30:107–14. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick AF, Charlton J. London: Office of Population Censuses and Surveys; 1995. Morbidity statistics from general practice. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes JE, Barraclough BM, Hamblin LG, White JE. Psychiatric symptoms in dermatology patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:51–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attah Johnson FY, Mostaghimi H. Co-morbidity between dermatologic diseases and psychiatric disorders in Papua New Guinea. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:244–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fortin M, Dubois MF, Hudon C, Soubhi H, Almirall J. Multimorbidity and quality of life: A closer look. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Schork NJ, Ellis CN. Depression modulates pruritus perception: A study of pruritus in psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and chronic idiopathic urticaria. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:36–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Picardi A, Abeni D, Renzi C, Braga M, Melchi CF, Pasquini P. Treatment outcome and incidence of psychiatric disorders in dermatological outpatients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:155–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renzi C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Agostini E, Baliva G, Pasquini P, et al. Association of dissatisfaction with care and psychiatric morbidity with poor treatment compliance. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:337–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:846–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent G, Al’Abadie MS. Psychologic effects of vitiligo: A critical incident analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:895–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanigan SW, Cotterill JA. Psychological disabilities amongst patients with port wine stains. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:209–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lever WF. Pemphigus. Medicine. 1953;32:1–123. doi: 10.1097/00005792-195302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanley JR, Amagai M. Pemphigus, bullous impetigo, and the staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1800–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namazi MR. Prescribing antidepressant drugs for pemphigus patients: An important point to keep in mind. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noorbala AA, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Yasamy MT, Mohammad K. Mental health survey of the adult population in Iran. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:70–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayrshofer F, Hertl M, Sinkgraven R, Sticherling M, Pfeiffer C, Zillikens D, et al. Significant decrease in quality of life in patients with pemphigus vulgaris: Results from the German Bullous Skin Disease (BSD) Study Group. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:431–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodiamont P, Peer N, Syben N. Epidemiological aspects of psychiatric disorder in a Dutch health area. Psychol Med. 1987;17:495–505. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regier DA, Boyd JH, Burke JD, Jr, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, et al. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:977–86. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800350011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wessely SC, Lewis GH. The classification of psychiatric morbidity in attenders at a dermatology clinic. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:686–91. doi: 10.1192/s0007125000018201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B. Psychiatric disorders in patients attending a dermatology outpatient clinic. Dermatology. 1998;197:230–4. doi: 10.1159/000018002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]