Abstract

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis constitutes about 10% of all cases of tuberculosis, and cutaneous tuberculosis makes up only a small proportion of these cases. Despite prevention programs, tuberculosis is still progressing endemically in developing countries. Commonest clinical variant of cutaneous tuberculosis in our study was lupus vulgaris seen in 55% patients followed by scrufuloderma seen in 25% patients followed by orificial tuberculosis, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum seen in 5% each. The commonest site of involvement was limbs seen in 50% patients followed by neck seen in 25% patients, face in 15%, and trunk in 10% patients. Maximum percentage of patients (55%) had duration of cutaneous tuberculosis between 6–12 months followed by 35% between 13–24 months, 5% had duration of cutaneous tuberculosis less than 6 months, and the rest 5% had duration more than 24 months. The commonest histopathological feature in our study was tuberculoid granuloma with epitheloid cell and Langhans giant cells seen in 70% patients, hyperkeratosis was seen in 15% patients and AFB bacilli were seen in 5% patients.

Keywords: Chancre, cutaneous, gumma, lupus vulgaris, scufuloderma, tuberculids, tuberculosis

Introduction

Cutaneous involvement is a rare manifestation of tuberculosis (TB).[1] Diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis (CTB) is complicated and requires a full work-up, including a detailed history and physical examination, careful consideration of clinical presentation, skin biopsy with histological analysis, and special staining methods for identification of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and the use of other diagnostic tests, such as chest X-ray and sputum culture.[2–4]

Materials and Methods

We selected 30 patients who were clinically suspected to have cutaneous tuberculosis. To rule out tuberculosis in other organs, chest X-ray and sputum-smear examination for AFB on three consecutive days were performed for all patients. Skin biopsy was performed in all cases and examined after staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Skin biopsy, Mantoux test, chest X-ray, haemogram, and serum biochemistry were performed on these patients. Other tests including fine needle aspiration cytology, lymph node biopsy, and radiological imaging were conducted when clinically indicated.

Results

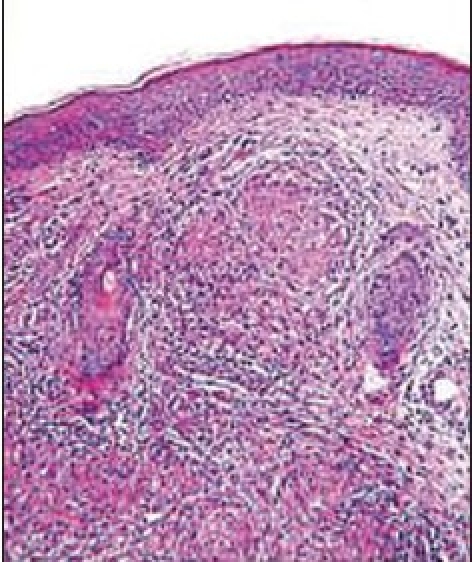

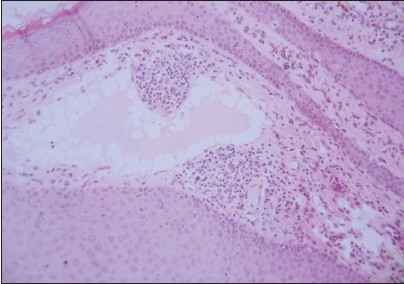

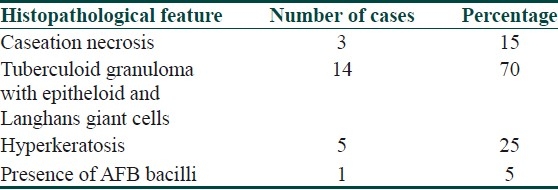

In our study, maximum (50%) patients were between 21–30 years, 20% patients were between 31–40 years, 10% patients were between 11–20 years, and 41–50 years each and 5% patients were between 0–10 years and 51–60 years each. Males outnumbered females and male to female ratio was 1.5: 1. Commonest clinical variant of cutaneous tuberculosis in our study was lupus vulgaris [Figure 1a and b] seen in 55% patients followed by scrufuloderma [Figure 2] seen in 25% patients followed by orificial tuberculosis [Figure 3a and b], tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum seen in 5% each [Table 1]. The commonest site of involvement was limbs seen in 50% patients followed by neck seen in 25% patients, face in 15% and trunk in 10% patients. Maximum percentage of patients (55%) had duration of cutaneous tuberculosis between 6–12 months followed by 35% between 13–24 months, 5% had duration of cutaneous tuberculosis less than 6 months, and rest 5% had duration more than 24 months. The commonest histopathological feature in our study was tuberculoid granuloma with epithelioid and Langhans giant cells seen in 70% patients, hyperkeratosis was seen in 15% patients and AFB bacilli were seen in 5% patients [Table 2]. The Mantoux test positivity was seen in ten patients and varied from 10-24 mm in diameter.

Figure 1a.

Plaque of lupus vulgaris on the knee with central atrophy

Figure 1b.

Histopathology of lupus vulgaris showing noncaseasting granuloma with epithelioid and Langhans giant cells (H and E stain × 100)

Figure 2.

Scrufuloderma below the ear

Figure 3a.

Anal tuberculosis

Figure 3b.

Photomicrograph of perianal swelling showing hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with multiple lymph spaces in upper dermis (H and E stain, ×100)

Table 1.

Clinical variants of cutaneous tuberculosis

Table 2.

The histopathological feature of cutaneous tuberculosis

To conclude, although the incidence of CTB is rare, it should be considered in patients presenting with atypical skin lesions suggestive of an underlying infectious etiology.[5] The laboratory diagnosis of cutaneous tuberculosis is difficult.[6] Microbiological tests such as direct microscopy and culture are usually negative in cutaneous tuberculosis because it is paucibacillary. Histopathological findings are characteristic but not pathognomonic and are shared by other granulomatous diseases including leprosy, sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, and subcutaneous fungal infections.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Bravo FG, Gotuzzo E. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacGregor RR. Cutaneous tuberculosis. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:245–55. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00019-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutto AM, Solangi A, Khaskhely NM. Clinical and epidemiological observations of cutaneous tuberculosis in Larkana, Pakistan. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:159–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbagallo J, Tager P, Ingleton R. Cutaneous tuberculosis: Diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2002;3:319–28. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai-Chong JE, Perez A, Tang V. Cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:461–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sehgal VN, Jain MK, Srivastava GP. Changing patterns of cutaneous tuberculosis.A prospective study. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:231–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb04810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]