Abstract

We report a 48-year-old immunocompetent male, resident of Central India, who presented with slowly progressive asymptomatic multiple red lesions on different parts of body. On enquiry, the patient gave history of travel to Middle East 6 months back. Examination showed 10 crusted erythematous indurated plaques and nodules over forearms, left leg, right index finger, left wrist and dorsa of both feet. Histopathological examination of tissue biopsy showed multiple intracellular as well as extracellular leishmania donovan bodies. Keeping in mind the higher rate of side effects to pentavalent antimony, we treated this patient with oral miltefosine 50 mg bid and the lesions showed complete resolution over 4 months of therapy.

Keywords: Leishmaniasis, miltefosine, multifocal

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a clinically heterogeneous protozoan infection belonging to genus Leishmania and is transmitted by sandflies.[1] This condition is uncommon in the state of Maharashtra and is occasionally encountered in people travelling to Middle East, foreign immigrants and military personnel.[2] Current treatment option includes amphotericin B and its lipid formulations, pentamidine, miltefosine, and paromomycin.[3] We came across multifocal cutaneous leishmaniasis in an immunocompetent male and treated it with oral miltefosine.

Case Report

A 48-year-old immunocompetent male presented to our out-patient department with multiple red colored raised lesions on different parts of the body since 3 months. Initially, a single, red, raised lesion appeared on the forehead, which was associated with fever and chills. Then, many similar lesions appeared on other body parts like forearms, left leg, right index finger, left wrist and dorsa of both feet in the following 3 weeks. On enquiry, the patient gave a history of travelling to Saudi Arabia about 6 month back. Further enquiry revealed that he was bitten by insects during night sleep, when he only used to wear modesty garments. On examination, there were multiple erythematous plaques of sizes varying from 3 to 8 cm in diameter. All the lesions were slowly progressive in nature and showed ulceration and crusting with minimal oozing of blood stained discharge [Figures 1 and 2]. Some of the lesions were showing typical volcano like morphology [Figure 3]. His general and systemic examination was within normal limits. There was no associated enlargement of regional lymph glands.

Figure 1.

A single erythematous plaque on forehead

Figure 2.

Erythematous plaque topped with hemorrhagic crust on dorsa of right foot

Figure 3.

A plaque showing central ulceration resembling a volcano around left ankle

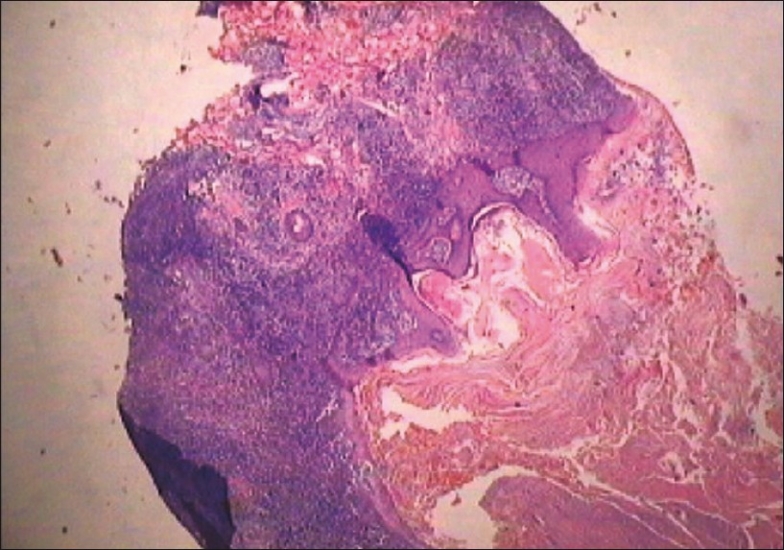

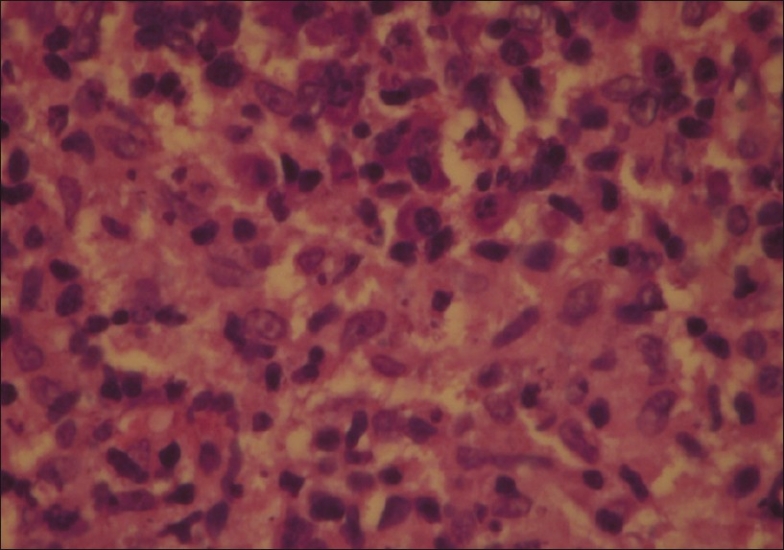

His blood biochemistry and complete blood count were within reference range. His hemoglobin was 13.6 g/dl, total leukocyte count 6600/mm3, serum creatinine 0.8 mg/dl, and blood urea nitrogen was 18 mg/dl. Serological studies for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus were negative. A differential diagnosis of disseminated fungal infection, atypical mycobacteriosis and sporotrichosis was entertained. Histopathology of lesional biopsy showed diffuse and dense granulomatous infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and histiocytes in superficial as well as deep dermis, along with abundant plasma cells [Figure 4]. Giemsa stained preparation showed leishmania donovan (LD) bodies intracellularly as well as extracellularly [Figure 5]. Bone marrow examination for parasite was negative. Abdominal ultrasound did not show any hepatosplenomegaly. However, culture of lesional tissue on Nicolle-Novy-McNeal (NNN) media was reported negative at the end of 4 weeks.

Figure 4.

Diffuse and dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate in whole of dermis (H and E, ×10)

Figure 5.

Amastigote stage of parasite (LD bodies) seen H&E stained tissue biopsy

With a working diagnosis of leishmaniasis and due to side effect profile of pentavalent antimonial, and the fact that the patient preferred oral medication, the patient was started on oral miltefosine (Impavido®) (2 mg/kg/day), 50 mg twice daily, on out-patient basis. Gradually, all the lesions showed resolution over 4 months of miltefosine therapy [Figures 6a and b]. Except two episodes of vomiting which were managed symptomatically, the patient did not report any significant side effects or any changes in biochemical parameters. As per telephonic conversation with the patient, he reported no relapse of skin lesion.

Figure 6.

(a) Forehead plaque showing complete resolution after 4 months of miltefosine therapy [compare with Figure 1]; (b) complete resolution of right foot plaques after 4 months of miltefosine therapy [compare with Figure 2]

Discussion

Our patient was diagnosed to have Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, given the geographic origin of the condition and the infecting parasite being either Leishmania major or Leishmania tropica. Most of the patients present with typical morphology and do not pose any diagnostic dilemma. Our patient presented with 10 lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis and posed a diagnostic confusion due to its multifocal nature. In an immunocompetent individual, natural evolution is that the condition remains localized to the site of parasitic inoculation and then resolves spontaneously over a period of 1 month to 3 years.[4] Leishmania species are transmitted by bites of infected sandflies (Phlebotomus species in the Old World and Lutzomyia species in the New World).[5,6] Until proven otherwise, any chronic cutaneous ulcer in a patient who has traveled between the 40th parallels is suspicious for leishmaniasis.[7] The gold standard for diagnosis is direct pathogen detection. Culture is frequently negative in cutaneous leishmaniasis (as in our case), and diagnosis may be made on demonstration of organism on either smear or culture or histopathology specimen.[8]

Standard treatment in multiple lesions is parenteral drug therapy. There are several injectable drugs available, such as the pentavalent antimonials, pentamidine, and liposomal amphotericin B, some of them with considerable toxicity.[9] Miltefosine (hexadecylphosphocholine) is an oral drug that was originally studied as an antitumor agent. After serendipitous laboratory finding that miltefosine was active against Leishmania in vitro and, after oral administration in laboratory animals, the drug was developed for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis or kala-azar.[10] Miltefosine inhibits phospholipid and sterol biosynthesis of trypanosomids and is effective in vivo against Leishmania.[5] Endogenous production of interferon-gamma (IFN γ) is necessary for killing of parasite in the macrophages.[11] Macrophages infected by Leishmania parasite have reduced activity of IFN γ; miltefosine enhances the IFN γ responsiveness of macrophages, thereby clearing the intracellular load of parasite. Miltefosine activates the macrophages to produce inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), leading to production of nitric oxide, the reactive radical necessary for killing of parasite.[12]

Our patient was started on oral miltefosine (Impavido®) in view of its minimal side effects and consequent better patient compliance with excellent results. The frequently reported side effects of miltefosine include vomiting, nausea and diarrhea.[13] Because miltefosine is teratogenic, women of child-bearing age need contraception and preferably miltefosine should be avoided as far as possible.[14] Apart from this, miltefosine is an ideal treatment option and can be used in all forms of leishmaniasis on out-patient basis.[15] In future, after lowering of cost, this drug may be used as a first-line agent in endemic regions of North-Eastern Indian states like Bihar and other countries in Indian subcontinent like Pakistan and Afghanistan. Miltefosine has been approved for oral and topical treatment of leishmaniasis.[16]

We hope that the drug becomes more affordable (current cost is US$2 per tablet) in future and has the potential to be used as the standard therapy for cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in India, where resistance to pentavalent antimony is very high (up to 30%) and intravenous liposomal amphotericin is prohibitively expensive even in developed countries. Guidelines for use of miltefosine have been drafted by Directorate of National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, New Delhi.[17] These guidelines have been developed for treatment of visceral and post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, in which the drug, miltefosine was used at a dose of 1.5-2.5 mg/kg for 28 days. Our patient did show definite, but incomplete resolution of lesions after 28 days; hence, the treatment was continued for 4 months. However, it cannot be said whether stopping of miltefosine therapy after 28 days would have resulted in clearing of lesions and it is a matter of conjecture. Our case has demonstrated the efficacy of miltefosine only in a single patient and, hence, more case studies are needed to support the above findings. It is urged to other investigators working in this field to publish their experience with miltefosine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Bailey MS, Lockwood DN. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright NA, Davis LE, Aftergut KS, Parrish CA, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Texas: A northern spread of endemic areas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:650–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerin PJ, Olliaro P, Sundar S, Boelaert M, Croft SL, Desjeux P, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: Current status of control, diagnosis, and treatment, and a proposed research and development agenda. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:494–501. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herwaldt B. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 1999;354:1191–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soto J, Soto P. Miltefosine: Oral treatment of leishmaniasis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:177–85. doi: 10.1586/14787210.4.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soto J, Arana BA, Toledo J, Rizzo N, Vega JC, Diaz A, et al. Miltefosine for New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1266–72. doi: 10.1086/383321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuber H. Leishmaniasis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;9:754–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S, Sivakumar R. Recent advances in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:55–60. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: Current and future management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2003;1:563–70. doi: 10.1586/14787210.1.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundar S, Jha TK, Thakur CP, Engel J, Sindermann H, Fischer C, et al. Oral miltefosine for Indian visceral leishmaniasis. N Eng J Med. 2002;347:1739–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray HW, Delph-Etienne Visceral leishmanicidal activity of hexadecyl-phosphocholine (miltefosine) in mice deficient in T cells and activated macrophage microbicidal mechanisms. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:795–9. doi: 10.1086/315268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wadhone P, Maiti M, Agarwal R, Kamat V, Martin S, Saha B. Miltefosine promotes IFN-gamma-dominated anti-leishmanial immune response. J Immunol. 2009;182:7146–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Æterna Zentaris. Impavido®? [last accessed on 2010 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.aeternazentaris.com/en/page.php?p=60andq=102 .

- 14.Sundar S, Gupta LB, Makharia MK, Singh MK, Voss A, Rosenkaimer F, et al. Oral treatment of visceral leishmaniasis with miltefosine. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93:589–97. doi: 10.1080/00034989958096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wöhrl S, Schnedl J, Auer H, Walochnik J, Stingl G, Geusau A. Successful treatment of a married couple for American leishmaniasis with miltefosine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:258–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walochnik J, Obwaller A, Gruber F, Mildner M, Tschachler E, Suchomel M, et al. Anti-acanthamoeba efficacy and toxicity of miltefosine in an organotypic skin equivalent. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;6:539–45. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Directorate of National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP) under Ministry of Health and Family welfare, New Delhi. Guidelines on use of miltefosine. [last accessed on 2010 Mar 12]. Available from: http://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/Guidelines%20on%20miltefosine.pdf.