Sir,

A long life is a cherished desire of every man, but all are not destined to enjoy it. The elderly are defined as those who are 60 years of age and above.[1] The population of the elderly in India is steadily growing and the number is already quite large. As per SRS estimation, in 2003, the elderly formed 7.2% of the total population of India.[2]

No cutaneous examination is complete without a careful evaluation of the nails of the patient. Nail changes associated with ageing are common in the elderly and include changes in color, contour, growth, surface, thickness, and histology.

The calcium content of the ageing nail is increased and the iron content is decreased.[3] Histologically, the keratinocytes of the nail plate are increased in size and have an increased number of ‘pertinax bodies’ (remnant of keratinocyte nucleus).[4] The nail bed dermis also shows thickening of the blood vessels and elastic tissue, especially beneath the pink part of the nail.[5] Nail growth decreases by approximately 0.5% per year between the ages of 20 and 100 years.[6]

There have not been many studies in our country on nail changes in ageing and the prevalence of nail disorders in the elderly. Hence, we have undertaken this study.

Elderly patients of 60 years and above were included in our study. Every second elderly patient attending the OPD each day was included in the study, irrespective of the presenting symptoms. A total of 100 patients were enrolled by this method that was designed to eliminate observer bias in the study. A detailed history of each patient was taken, after which we conducted a thorough general examination and an examination of the nail and hair. In all the suspected cases of onychomycosis we examined a KOH preparation of nail clipping microscopically to detect fungal infection.

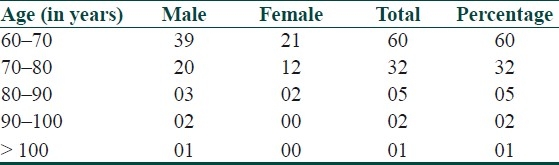

The following Table shows the age- and sex-wise breakup of the patients enrolled for the study [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of subjects

The youngest elderly patient was 60 years and the oldest was 101 years old. Six percent of the subjects reported that they had the habit of occasional nail biting.

The majority of the patients were not conscious of their nail changes and nail diseases. However, in 14 cases (14.28%) it was the presenting complaint.

General examination of the patients showed that 44 had mild conjunctival pallor, suggesting the presence of mild anemia. It was also seen that they suffered from various systemic diseases like hypertension (19%), diabetes mellitus (5%), COPD and bronchial asthma (5%), ischemic heart disease (4%), arthritis (2%), prostatic hypertrophy (1%), and parkinsonism (1%).

Out of 100 patients, 98 showed at least one change in the nails due to ageing. Two patients, both incidentally female, did not show any change due to ageing.

With regard to age-related color changes of nail plate, a pale, dull, and lustreless nail plate was seen in 73% of patients, opacity in 8%, and grey color in 6%.

As the age increases, lunular visibility decreases. In 31 cases, the lunula was visible. Among those who had visible lunula, 23 were from the age-group of 60–70 years. In these patients lunular visibility was maximum (100%) in the LF1 (first left finger, i.e., the left thumb) and RF1 (first right finger, i.e., right thumb), followed by 67.8% and 64.5% lunular visibility for the RT1 (right first toe) and RT2 (right second toe), respectively. Lunular visibility was very low to 0% in the other fingers and toes.

Among the age-related changes in the nail surface, prominent longitudinal ridges were the commonest (in 85%), followed by rough nails in 33% of the patients, transverse ridges in 23%, and lamellar split in 15% of cases.

Brittleness of the nail is a common condition related to aging. Twenty-six (40%) males and 8 (26%) females showed brittle nails. The prevalence of brittle nail was higher in the toe nails in both sexes. Among males, 25 had brittleness of toe nails, 5 had brittleness of finger nails, and 4 had brittleness of both finger and toe nails. Among females, 8 had brittle toenails, 2 had brittle fingernails, and 2 had brittleness of both finger and toe nails.

Onychauxis or thickening of the nail plate, which is associated with ageing, was noticed in 23% of the subjects, with the prevalence being 10% in the left great toe and 13% in the right great toe, followed by 7% in right fifth toe and 4% in left fourth toe.

With regard to changes in nail contour, increased transverse curvature was seen in five cases, pincer nail [Figure 1] in two, and platonychia in one case.

Figure 1.

Pincer nails

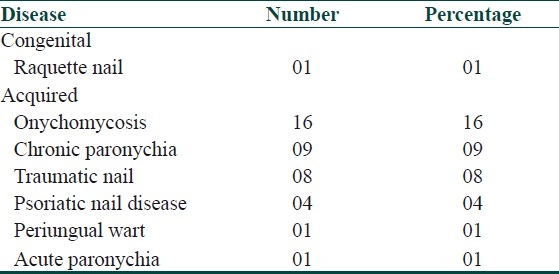

Table 2shows the prevalence of nail disorders in the elderly. Out of 33 cases of acquired disorders, the majority were infective disease. Onychomycosis was seen in 16%, followed by chronic paronychia [Figure 2] in 9%. A single disorder was seen in 31%, two disorders were seen in 4%, and three disorders were seen in 1% of the patients.

Table 2.

Prevalence of nail disorders

Figure 2.

Chronic paronychia with periungual warts

The prevalence of onychomycosis was 22% in women and 12% in men. The commonest change in onychomycosis was loss of lustre, subungual hyperkerotosis, onycholysis, brittleness, and color change with blackish brownish or yellowish discoloration.

The finger nails were involved in 10 patients and the toe nails in 12 patients.

Out of the nine patients suffering from chronic paronychia, five were male. Of them, three were retired, one was a farmer, and another jobless. Of the four female patients, three were housewives and one a maidservant. The right thumb, index, and ring fingers were affected in four cases each; the left thumb and right middle finger in three cases; the left index, middle, ring, and little fingers in two cases; and the right little finger and left toe in two cases each. Hence, overall, the right hand was found to be affected more commonly. Common changes seen in chronic paronychia were loss of cuticle and nail fold erythema and edema. Common nail plate changes were transverse furrows, loss of lustre, and thickening.

Traumatic nail disorders were the third most common disorder seen in the study, with eight patients affected. Subungual hematoma was seen in three cases, nail loss in two, and onycholysis in two. One case of splinter haemorrhage was also seen.

In our study we found that senile changes in elderly could be classified under four headings: (1) change in color, with emphasis on lunular color change; (2) change in contour of nail; (3) change in the surface of nail and brittleness of nails; and (4) gross change in thickness of nail, with presence of onychauxis.

The commonest change seen in the ageing nail was a pale, dull and lustreless appearance, which was apparent in 73% of the patients. The color of the ageing nail varied from yellow to grey and there was a dull opaque appearance.[7] Other authors have reported that the senile nail may appear pale, dull and opaque, with color varying from white or yellow to brown to grey.[5]

Though the lunula is often not visible in all fingers and toes, it is most consistently observed on the thumb, in the index finger, and the great toes.[8] The same was true in our study also. The lunular size decreased with age and this has been previously noted as an ageing-related nail change in elderly persons.[4] In our study, we found that the lunula was not visible in 69 cases and the visibility of the lunula decreased consistently with ageing.

Changes on the surface of the nail due to ageing can be seen as increased longitudinal furrowing or ridges and increased friability and fissuring.[9] Ageing is the commonest cause of onychorrhexis or superficial longitudinal ridges.[10] Transverse furrows/ridges are also found very frequently. The nails may be rough (trachyonychia, with lamellar splitting and fissuring). In our study we found prominent/increased longitudinal ridges in 85% of cases, with no significant difference between the percentages of finger and toe nails involved. Transverse ridges/furrows (22%) were seen in the toe nails in all 22 patients (mainly in the great toe nails), while it was seen in the finger nails in 2 cases. Rough nail (33%) was also seen mostly in the toes.

Repeated cycles of hydration and dehydration, as occurs during excessive domestic wet work or with overuse of dehydrating agents, nail enamel, nail enamel removers, or cuticle removers may precipitate brittle nails. Brittle nail is a common finding in the elderly.[3] Similar observations have been made by Lubach et al.[11] In their study on elderly patients of 60 years and above, the incidence of brittle nails was 31% in males and 36% in females. The first three fingers of the dominant hand are particularly susceptible to brittle nails. In our study, we found the prevalence of brittle nails to be 34%. The incidence of brittle nails is higher in the toe nails in our study because our study population mainly comprised poor patients who walk barefoot or use ill-fitting shoes and sandals. Constant low-grade trauma hastens the onset of brittle nail changes seen in elderly patients.

Senile nails may have an increased transverse curvature and a decreased longitudinal curvature.[7] Flattening of the nail plate (platonchia), spooning (koilonychia), and pincer nail deformity are found more frequently in the elderly.[5] In our study, we observed increased transverse curvature in five cases. We also found two cases of pincer nail and one case of platyonychia. No case of koilonychia was seen in our study.

The prevalence of onychomycosis increases with age and reaches nearly 20% in patients over 60 years.[12] In our study we found the prevalence of onychomycosis to be 15%. Among the elderly, onychomycosis is more common in men than in women.[13] In our study we found that the prevalence of onychomycosis in women was 22%, whereas in men it was 12%. The most common type of onychomycosis observed in our study was distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis; this has also been reported earlier.[14] Chronic paronychia (9%) was also not uncommon in the present study. The right hand, being the working hand of the majority, is found to be predominantly affected. Most of the patients in our study were from the poorer section of the society. Many of them walked barefoot most of the time. Due to their unsanitary environment, their feet are usually exposed to dirty and wet conditions. The above factors probably induced and hastened the onset of brittle nails in our study group. The occupation of many patients (as well as household work, especially in women) makes their hands and feet vulnerable to repeated minor trauma and exposure to water, chemicals and irritants for relatively long periods. These factors may have contributed to the ageing-related changes in our study group, besides contributing to onychomycosis and paronychia.

In our study we found six cases of psoriasis, out of which four presented with nail changes. The prevalence of nail involvement in psoriasis was thus 67%. Nail involvement is common in psoriasis and has been reported in between 50%[15] and 56% of patients.[16] It is estimated that over their lifetime 80%–90% of patients with psoriasis will suffer from nail disease.[17] Pitting was the most common finding seen in all the four cases in our study, consistent with the descriptions by others.[18] Pitting was more common in the finger nails than on the toe nails and were scattered rather than forming a regular pattern. Other common findings were subungual keratin deposits and onycholysis. Yellowish discoloration and loss of texture were also common. Though loss of cuticle has been a common finding reported by some workers[3] it was not found in the present study.

As socioeconomic conditions improve and awareness increases, more and more geriatric patients will visit dermatologists with problems of their nails. Dermatologists will have to be prepared to handle such common geriatric problems in an organ that is part and parcel of their discipline.

References

- 1.WHO Scientific group, Health of elderly, TRS NO. 779, WHO, General. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park K. Park's Text Book of Preventive and Social Medicine. 9th ed. Jabalpur India: Banarasidas Bhanot; 2007. Preventive Medicine in Obstetrics Paediatrics and Geriatrics; p. 471. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baran R, Dawber RP. The nail in childhood and old age. In: Baran R, Dawber RP, editors. Diseases of the nails and their management. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1994. pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis BL, Montgomery H. The senile nail. J Invest Dermatol. 1955;24:11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen PR, Scher RK. Aging. In: Hordinsky MK, Sawaya ME, Scher RK, editors. Atlas of hair and nails. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 213–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh G, Haneef NS, Uday A. Nail changes and disorders among the elderly. Indian J Dermatol Veneveol Leprol. 2005;71:386–92. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.18941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baran R, Dawber RP. The ageing nail. In: Fry L, editor. Skin problems in the elderly. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1985. pp. 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flukman P. Anatomy and physiology of the nail. Dermatol Clin. 1986;3:373–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baran R, Dawber RP. The nail in childhood and old age. In: Baran R, Dawaber RP, editors. Diseases of the nails and their management. Oxford: Backwell Scientific; 1984. pp. 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzberg M. Nail signs of systemic disease. In: Hordinsky MK, Sawaya ME, Scher RK, editors. Atlas of hair and nails. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubach D, Cohrs W, Wurzinger R. Incidence of brittle nails. Dermatologics. 1986;172:144–7. doi: 10.1159/000249319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo DS. Cutaneous fungal infections in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:33–50. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinberg JW, Vafaie J, Scheinfeld NS. Skin infections in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta AK, Lynde CW, Jain HC, Sibbald RG, Elewski BE, Daniel CR, 3rd, et al. A higher prevalence of onychomycosis in psoriatics compared with non- psoriatics: a multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:786–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaias N. Psoriasis of the nail, a clinical- pathology study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur I, Handa S, Kumar B. Natural history of psoriasis: a study from the Indian subcontinent. J Dermatol. 1997;24:230–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salomon J, Szepietowski JC, Proniewicz A. Psoriatic nails: a prospective clinical study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:317–21. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babu RK. Nail and its disorders. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL Textbook and atlas of dermatology. 2nd ed. Mumbai: Bhalani Publishing House; 2001. pp. 763–98. [Google Scholar]