Abstract

An estimated 8 million children, mostly birth to approximately 6–8 years of age, live in institutions worldwide. While institutional environments vary, certain characteristics are common, including relatively large groups; high children:caregiver ratios; many and frequently changing caregivers; homogeneous grouping by age and disability status; periodic graduations to new groups of peers and caregivers; and an “institutional style of caregiving” that minimizes talking, provides rather dispassionate perfunctory care, and offers little warm, sensitive, contingently-responsive caregiver-child interactions. The development of children in residence is usually delayed, sometimes extremely so, in every physical and behavioral domain. Although efforts are being made in many countries to care for children without permanent parents in family environments (e.g., domestic adoption, foster and kinship care, reunification with biological parents), it is not likely that transitions to family alternatives will be completed in all countries in the near future; thus, institutions are likely to exist for many years if not decades. But institutions need not operate in the current manner; they can be modified to be substantially more family-like in structure and in the behavior of caregivers. Research indicates that when such changes are made the development of children, both typically developing and those with special needs, is improved substantially. Based on the available literature and the authors' experience, this paper describes steps that can be taken to implement such changes in residential institutions for infants and young children.

Nearly every country has housed children without permanent parents in orphanages and other residential institutions at one time in its history, and it is estimated (Human Rights Watch, 1999) that approximately 8 million children currently reside in institutions worldwide, mostly in low-resource countries. Although family alternatives to institutions are preferred, this paper assumes that institutions are likely to continue to exist in many countries for many years. Institutions worldwide tend to have certain common characteristics that contrast sharply with those of families; resident children's development is substantially delayed; and research shows that changes in the structure, operation, and behavioral nature of institutions can produce marked improvement in children's development. But changing decades-long traditions in an entire institution is a challenging endeavor with little research available to guide the process, so this paper reports the experience of the authors, who have been involved in implementing family-like interventions in orphanages in several countries, on methods of implementing change in institutions.

Rationale for Institutional Change

The Nature of Institutions

Children without permanent parents include those who have no birth parents (i.e., “true orphans”) and those who have one or both parents who for a variety of reasons are unable or unwilling to raise their children (i.e., “social orphans”). Worldwide, most of these children are reared in informal situations, but some reside in institutions, mostly orphanages but also hospitals (especially newborns) and other facilities. Most of the published literature pertains to orphanages, so this term will be used in these contexts.

While orphanages vary in their physical and operational characteristics and the caregiving provided to children, a review of the published literature that spans the last six decades reveals certain common characteristics of orphanage environments in a variety of countries (Rosas & McCall, 2010). Specifically, orphanages tend to house large numbers of children (typically from 35 to 100, but some up to 600 children at one time). Children are housed in rather large groups, approximately 9 to 16 per ward but sometimes up to 70, and the number of children per caregiver during waking hours averages approximately 6–8, although it is much higher in some institutions. These groups tend to be homogeneous by age, and children with disabilities are usually placed in separate wards or even in separate institutions. Caregivers tend to have minimum educational backgrounds and may receive some specialized training, typically in health, safety, and nutrition, but often not in the behavioral care of young children.

Staffing patterns in orphanages usually result in children experiencing many different and changing caregivers over the course of a few years. For example, caregiver turnover may be high due to low pay, caregivers often work 24-hour shifts and then are off for three days, caregivers may be given numerous days of vacation, substitutes are assigned wherever needed rather than consistently to one or another ward, and children may be graduated to new wards of peers and caregivers when they reach certain developmental milestones or even transferred to other orphanages at certain ages. Thus, while “only” 9–12 caregivers may be assigned to a single ward per week, the net effect of all of these practices can be that a child is exposed to 60–100 different caregivers during the first 19+ months of life and no caregiver today whom the child saw yesterday or will see tomorrow (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008).

Caregiver behaviors with children tend to be perfunctory with little talking and even less conversation, little interaction outside of routine caretaking duties, minimum responsiveness to children's individual needs (e.g., such as crying), caregiver-directed rather than child-directed interactions when they do occur, and almost no attempt by caregivers to form relationships with children (for sample narrative descriptions, see Muhamedrahimov, 1999; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008). Thus, there are few warm, caring, sensitive, contingently-responsive caregiver-child interactions and a constantly changing set of caregivers that precludes consistency of care and relationships.

Institutional versus family environments

This environment is almost totally opposite to that provided by most families, which throughout nearly all human history has been the preferred environment in which to rear children. Although variations exist worldwide, the typical family environment consists of a small group of children, a mixture of different ages and genders including children who are typically developing and those with special needs, a few primary caregivers (parents) responsible for raising the children helped by a relatively small set of secondary caregivers (e.g., grandparents, relatives, friends) all of whom are relatively consistent and stable in the children's lives. Further, the children:caregiver ratio is typically low, and most parents provide children with much oneon-one time and warm, sensitive, and contingently-responsive interactions that are more child-directed than in institutions. Attachment theory, for example (e.g., Ainswoth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1975; Bowlby, 1969), emphasizes all of these characteristics as crucial for typical social-emotional and other development.

The development of children in institutions

Most developmental theory, empirical evidence, and common sense stipulate that children residing in such orphanages tend to be delayed in their development in every physical and behavioral domain, sometimes very substantially (Gunnar, 2001; MacLean, 2003). For example, institutionalized children are physically smaller in height, weight, and head and chest circumference (van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Juffer, 2007). Even in orphanages that provide adequate medical care, nutrition, sanitation, and safety but inadequate psychosocial environments, nearly half the children can be below the 10th percentile and 92%–97% below the median of physical growth standards for parent-reared children in that country (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005). Similar delays occur for general behavioral development. Institutionalized children on average are more than a standard deviation below parent-reared children on tests of general behavioral development and IQ (van IJzendoorn, Luijk, & Juffer, 2008), and it is not uncommon to find as many as 80% of young children scoring below a developmental quotient of 70, which would occur in only approximately 2.2% of USA parent-reared children (McCall, Groark, Fish, & The Whole Child International Team, in press).

Also, institutionalized children have immature social-emotional behavior, in which they are often indiscriminately friendly, running up and hugging strangers, and 65%–85% may have disorganized attachment relationships with caregivers as reflected in a D classification of their behavior in the Strange Situation Procedure (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; Vorria, Papaligouria, Dunn, Van IJzendoorn, Steele, Kontopoulou et al., 2003; Zeanah, Smyke, Koga, Carlson, & the Bucharest Early Intervention Project Care Group, 2005).

Long-term consequences

Exposure to such orphanages early in the lives of children is associated with a great variety of long-term deficiencies and problems. If children are adopted, usually into highly educated and resourced families, before the age of 6, 12, or 18 months depending on the nature of the institution and the particular developmental outcome, they may have no unusual developmental delays or problems (at least through adolescence). However, higher than expected rates of developmental delays and problems occur in adopted post-institutional children including delayed physical and general behavioral development and higher rates of problems with respect to executive functioning (e.g., attention, memory, inhibitory control, sequencing, rule shifting, compliance), social-emotional behavioral regulation, relationships with parents and peers, externalizing (e.g., aggressiveness), and internalizing (extreme shyness and withdrawal), especially as such children emerge into late childhood and adolescence (Gunnar, 2001; MacLean, 2003; McCall, van IJzendoorn, Juffer, Groark, & Groza, 2010). Further, broadly similar kinds of problems apparently persist well into adulthood (Julian, 2009).

The Future of Orphanages

Clearly, something should be done worldwide to provide better environments to children without permanent parents.

Many international advocacy organizations (e.g., UNICEF, USAID) promote several types of family care as alternatives to institutions, and a review of the literature indicates that children display better development in nearly all domains if they are reared in adoptive, kinship, or non-relative foster care than in institutions (Julian & McCall, 2010; Nelson, Zeanah, Fox, Marshall, Smyke, & Guthrie, 2007). It is less clear that they do better if reunified with their biological parents, at least without services and supports that can help the biological parents overcome the circumstances that originally led to placing the child in an institution (Julian & McCall, 2010). Although advocates sometimes argue explicitly or implicitly that essentially any family environment is better for children than any institution (e.g., Moore & Moore, 1977), this is unlikely to be uniformly true (Julian & McCall, 2010; but see Dobrova-Krol, van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Juffer, 2010); in any case the quality of care in adoptive, foster, and biological families certainly matters. Similarly, the quality of care in orphanages also matters. The published literature (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2008; Rosas & McCall, 2010) shows very substantial variations in the general behavioral development of children residing in orphanages, and comprehensive intervention programs designed to improve the caregiving environment in orphanages using existing staff have been successful at improving children's development (McCall, Groark, Fish, Harkins, Serrano, & Gordon, in press; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

Advocates typically focus energy and resources on developing kinship and non-relative foster care and domestic adoption as alternatives to institutionalization as well as services to support parents to keep their children rather than to relinquish them or to be able to take their children back from the orphanage. These efforts are certainly worthwhile, but they often come with the overt or defacto admonition that nothing should be done to improve orphanages (e.g., Groark, McCall, & Li, 2010), which is considered a waste of resources that otherwise could be devoted to alternative family care.

However, from a practical standpoint, the transition in a low-resource country from institutions to family care alternatives likely faces a variety of challenges, including cultural and religious aversion to adoption or rearing someone else's child, insufficient numbers of families with a desire and financial means to rear children even with government support, a variety of thorny policy issues pertaining to providing support and incentives for families to take children, inadequate preparation for and professional support to help parents deal with the special problems they are likely to face, and the greater willingness of parents to adopt or foster young and typically developing rather than older children or those with special needs (McCall et al., 2010). Indeed, even high-resource countries took decades to complete the transition from orphanages to family care, so it is likely that orphanages in low-resource countries will still provide care for substantial numbers of children for years to come.

While advocates lament devoting financial resources to improving orphanages that otherwise could be used to support family alternatives, the actual situation may not be so clearly dichotomous. In some low-resource countries, financial resources may exceed the number of families willing to adopt or provide foster care (e.g., Groark et al., 2010). Further, family care is generally cheaper than institutional care, so as family care increases the cost savings may be returned to improving orphanages. Finally, while there is some cost to changing an orphanage, the changes may be maintained for little or no additional resources (e.g., The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

Consequently, although family alternatives are preferred, from a practical standpoint, it seems reasonable to consider the possibility of improving the remaining orphanages to be more family-like to improve the development of children who must remain there in addition to those who are able to live in families.

Potential Changes in Orphanages

What should be changed?

Many orphanages are globally and severely deficient in the environment and care they provide children (Gunnar, 2001). The 1990s orphanages in Romania are perhaps the best known example in which every aspect of the environment and care for children was appallingly deficient. In other orphanages, medical care, sanitation, safety, nutrition, and the availability of toys and equipment may not be as deficient, but the psychosocial environment nevertheless often is (e.g., Hodges & Tizard, 1989; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2005, 2008). Indeed, perhaps the most common deficiency across most orphanages is that children experience too many and changing caregivers who do not provide warm, caring, sensitive, and contingently-responsive interactions with children. This situation appears to derive from tradition, the group care structure of the institution, typical work schedules and staffing procedures, and a psychological unwillingness of caregivers to get close to children almost all of whom soon leave their care for one reason or another (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; Tizard & Hodges, 1989). Thus, both “structural” and “behavioral” characteristics of orphanages converge in support their current environments and both should be the focus of efforts to change orphanages to improve the psychosocial aspects of orphanages and children's development.

More specifically, caregivers can be trained to be more nurturing and to provide more warm, caring, sensitive, and contingently-responsive interactions with children, especially during routine caregiving activities but also during free play. Of course, parents vary in how they provide such care to their own children, but basically caregivers should be encouraged to “love these children like you would love your own.” Caregivers generally do not have much training in the behavioral aspects of the development and care of young children, especially early intervention and other techniques to care for children with disabilities and special needs. Such training needs to be very practical, not predominately theoretical (Groark et al., 2010), and focused on concrete behaviors that caregivers should implement in their interactions with children. Consequently, some training in these matters is likely to convey not only useful new information but to also encourage--even give “permission” to--caregivers to behave with orphanage children in ways more typical of parents with their own children.

But training alone is rarely very effective (Kelley, 1999); it requires two additional circumstances. First, monitoring, mentoring, and positive supervision are typically necessary to help and encourage caregivers to apply on the wards what they learn in training. Unless there are supervisors who in partnership with caregivers champion the new behaviors and continuously encourage caregivers to implement them on the wards, behavioral changes are unlikely (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). Second, caregivers need to work in a physical and operational environment that allows them to implement their training, and most orphanages will need a set of structural and staffing changes so that there are fewer and more consistent caregivers who have the time and opportunity to interact with fewer children in more psychosocially appropriate ways.

Effectiveness of orphanage changes

Over the past several decades, a variety of attempts have been made to improve orphanage children's development (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al., 2008; Rosas & McCall, 2010). Some have consisted of having additional personnel provide supplementary stimulation to infants and toddlers typically for a few minutes every day for several weeks. Such interventions have been shown to improve children's behavioral development a small amount, more for children with lower initial developmental levels, or to prevent the progressive decline that occurs in unstimulated children; but there is little or no long-term benefit once the supplementary stimulation terminates. Of course, more extensive nurturing continued over longer periods of time might have larger and more persistent benefits; although such programs exist, they have not been formally evaluated or published.

More comprehensive attempts to change the entire orphanage and the behavior of regular orphanage staff have been much more successful, especially if implemented in orphanages in which the initial developmental levels of resident children are quite low. Such interventions may involve both training and structural changes and the more comprehensive and intensely implemented they are, the better the results (Rosas & McCall, 2010).

For example, in the most comprehensive and successful orphanage intervention, caregivers were provided with extensive training on the behavioral development of young children and practical ways of providing warm, sensitive, contingently-responsive care and child-directed interactions with children (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008). A system of mentoring and supervision was established to help caregivers implement the training on the wards with both typically developing children and those with a broad range of disabilities. Moreover, a variety of structural changes were introduced, including 1) reducing group sizes from 12–14 to 6–7, 2) integrating such groups by age (birth to 4 years) and disability status, 3) assigning two primary caregivers and four secondary caregivers to the smaller groups, 4) staggering work schedules so that one of the two primary caregivers was present for most of the children's waking hours throughout the week, 5) assigning substitutes to particular groups, 6) eliminating transitioning to new groups so children stayed with the same caregivers and many of the same peers throughout their residency in the orphanage, and 7) instituting family hour in which visitors were prohibited and caregivers were to spend time with their assigned children for an hour in the morning and an hour in the afternoon (free play).

Relative to children in a training only and a no-treatment orphanage, children in this maximum intervention condition 1) improved in height, weight, and chest circumference; 2) increased their general behavioral development scores substantially, including personal-social, motor, communication, and cognition; 3) showed more mature and typical social interaction and engagement with their caregivers; and 4) were 2.5 times more likely to display organized attachment behavior with their caregiver. Some of these improvements were among the largest ever reported. For example, typically developing children improved from an average DQ of 57 to 92 = 45 DQ points, and children with disabilities improved on average from DQ=23 to 42 = 19 points (27% increased more than 30 points and 14% increased more than 40 points). Moreover, although caregivers were initially skeptical or resistant to the changes, fearing they would create more work for them and that caregivers would be unable to handle mixed-age groups and children with disabilities, after 2–3 years of the intervention just the opposite was the case—caregivers reported greater reductions in job stress, anxiety, mild depression, inflexibility, work overload, and difficulties working with children with disabilities (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

Implementing Orphanage Change

Implementing such substantial changes in the very core structural operation of an orphanage and changing the traditional behavior of caregivers is not an easy task, and unfortunately the scholarly literature has more to say about programs of change than about how to implement them (Fixsen, Thomas, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Groark & McCall, 2008). Given the lack of research on implementation, case studies will need to suffice until more systematic and experimental evidence is available. Consequently, what follows is a description of the authors' experience accumulated in the USA (Groark & McCall, 2008), Russian Federation (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008), Central America (McCall et al., in press), and more recently China on how to implement such changes. These procedures fit parts of the more comprehensive scheme offered by Wandersman, Duffy, Flaspholer, Noonan, Lubell, Stillman et al. (2008), and will need to be modified to fit the particular residential institution, culture, resources, and other factors that may be idiosyncratic to the particular situation and discovering these factors and working with them is part of the implementation process. Although these procedures were developed specifically for orphanages, the general principles also might be useful to guide changes in non-residential group care, including early care and education programs that often lack the same features promoted here (The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008).

Step 1: Developing a Local Team

Changes in decade-old traditional structures and practices are more likely to be accepted, supported, implemented, and successful if they are generated from within the institution, locality, and country. But changes often are stimulated from outside the institutions that are to be changed by local or national policy makers, academics, and professionals from other countries. Interventions that are created outside the institution and its locale are often viewed skeptically by the people who are needed to support and implement them and later to expand them to other institutions; change is challenging under the best circumstances, but it is easier to dismiss if the proposed changes are “someone else's program, not ours.”

Thus, the instigators of change need to organize a local team of stakeholders that might include national and local policy makers and relevant administrators, academics and service professionals who are respected for their relevant expertise and experience, and directors and senior staff of institutions, especially the institution(s) likely to be targeted for changes. Private meetings with such potential stakeholders might assess their receptivity toward possible changes and their willingness to participate. Members of groups need to respect each other and work well together, so possible political and personal antagonisms need to be assessed and avoided if possible. Members also need to bring to the table something necessary for a successful project now or in the future, including expertise, local knowledge of institutions, financial resources, policy influence, and the operation of a target institution. This local team should participate in Step 2 below and meet periodically thereafter to monitor the progress of the intervention.

Although this team needs to be conducted with an attitude of equality and collaboration, there is no substitute for a strong, fair, respected, neutral, trusted leader of the project (Groark & McCall, 2008). The leader should have some relevant experience and be committed to but somewhat independent of the actual project. Sometimes outside consultants, who have expertise and are neutral with respect to other stakeholders, are useful as the project director or implementation specialists (Fixsen et al., 2005).

Step 2: Promoting the Desire and Commitment for Change

It is imperative that the local team and especially the orphanage director and senior staff, often consisting of an assistant director who manages staff schedules and child assignments and specialized professionals, are energized and committed to the philosophy and basic changes that need to take place. This consensus and commitment are necessary to ride out the inevitable difficulties and initial uncertainties and resistance of staff, minimize senior staff rivalries (e.g., between medical and behavioral staff), and decrease the likelihood of one or two senior staff undermining the changes. Generally, orphanage staff are dedicated individuals who want to help resident children, but decades of tradition and lack of knowledge of alternatives may blind them to the possibilities for change that might improve children's development.

Logic model strategy

A contemporary program development strategy is to conduct logic model sessions (Groark & McCall, 2005; W. K. Kellogg Foundation, 2000), initially with directors and senior staff and later with line staff, of possible goals and general strategies for meeting them. The task for the independent leader of these structured discussions is to get the participants to discover the changes to be made on their own, thereby building ownership and commitment to enacting them.

The logic model discussion begins socratically by declaring that the consensus through human history is that the family is the best environment in which to rear children and then having the group identify the characteristics of the family that make it the best environment for rearing children. This discussion leads to the principles of small groups, primary caregivers, few and stable caregivers, mixed or integrated groups (ages, genders, special needs children), and few if any transitions to other caregivers or families (e.g., through death, divorce, disease, armed conflict). In addition, the behavioral characteristics of good parents should be discussed, including warm, sensitive, contingently-responsive, and child-directed interactions. These characteristics are listed on one column of a chalkboard or flip chart.

Next, participants are asked what the circumstances are in the orphanage(s) for each of these characteristics. It should be readily apparent that the environment at the orphanage is nearly opposite to the environment of the family for each of the characteristics listed above.

The third stage is to ask socratically if the group agrees that the family characteristics are desirable for the orphanage. If so, then what could be done to change the orphanage to be more like a family with respect to each of these characteristics? This discussion is largely limited to setting goals (e.g., smaller groups, primary caregivers, etc.) rather than the details of how to actually achieve such changes. The end result should be consensus and some commitment and enthusiasm for “an ideal orphanage.”

Subsequent sessions address further questions, such as, what would be the first steps to achieving each of these goals; what are the resources necessary; what are the challenges to implementing them; what indices or measurements could be made that would testify that they have been achieved; and what do we expect the orphanage, caregivers, and children to be like once such changes are completely implemented? This is a “blue sky activity” in which directors and senior staff dream without holding back of how the institutional environment would look and operate if all the changes were successfully implemented. This provides an ideal conceptual model that describes the proposed environment, staff attitudes, and child outcomes, and this activity not only provides clear definitions of goals but drives implementation. It is often helpful to have a few key phrases that capture these desired goals in ordinary language, such as “love these children like you would love your own,” let us create a “more family-like environment,” and “let's give it a try,” the latter phrase to be used by a director when staff are uncertain or resistant. Generally, the major purpose is to build consensus on a common set of goals and changes to be made and engender some enthusiasm and commitment to implementing them.

Individual meetings with key staff may be necessary to sense their commitment, answer their questions, address their uncertainties, and inquire about the enthusiasm of other senior staff. Further, “champions” need to be developed and supported, both from the ranks of senior staff of the orphanage and local administrative, political, academic, and practice professionals who have a stake in the operation of the orphanage. These individuals should be part of the local team (Step 1), participate in the initial logic model process (Step 2), and support orphanage staff in their commitment to change.

Step 3: Training

The training of orphanage staff is typically designed to encourage more warm, caring, sensitive, and contingently-responsive caregiving interactions with children. Training materials specifically designed for orphanages are available (e.g. The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team, 2008; www.fairstart.net; www.globalorphanage.net), and some materials aimed at non-residential child care workers and parents may also be appropriate (Bradekamp & Copple, 1997.). Senior staff and consultants should select the training materials, modify and supplement them to fit local circumstances and needs, and determine the amount of training and how it will be scheduled and implemented.

Step 4: Supervision, Mentoring, and Monitoring

Some system of mentoring and monitoring staff needs to be developed that will encourage caregivers to incorporate training in their behavior on the wards with children. This is likely to involve the trainers, one or more training consultants, but mainly senior staff of the orphanage who have or could have some professional and supervisory responsibilities. Training should include material on supervision as well as being supervised and a structured system of observation and guidance for each caregiver.

This system of observation is conducted with each caregiver individually. The observations can include a checklist with strengths and challenges that were observed, or the observations might be videotaped and critiqued together. Ideally the observations should be collaborative, reflexive sessions initiated soon after the training. They should include target behaviors to improve and solutions for improvement. Follow-up supervision is scheduled and these records are reviewed.

Step 5: Data and Information Gathering for Structural Changes

This step determines the current status of the institution through review of documents, facility blueprints, interviews with the administrators, and a walking tour of the wards and grounds. The information to be obtained pertains to ward assignments, staff scheduling, and the physical structure of the wards. This information may be gathered anytime before this point in the total process.

Current ward assignments should be charted in the manner of Table 1, which includes a listing of each ward, the current number of children in that ward, the age range of those children, the ages of most children in that ward, the total number of caregivers assigned to the ward per week, the number of caregivers present at any one time during waking hours, and the children:caregiver ratio during waking hours. This information is supplemented by knowledge of the configuration of the physical characteristics of each ward, including approximate size of the ward; location of toilets, bathing facilities, and sinks; location of entrances to the outside and to support rooms; and available furniture and equipment. This information is necessary to determine how the physical facility can be modified to create smaller groups of children, either by erecting walls or inserting partitions. It may be necessary for all children in the current groups to sleep in the same room but have separate daytime quarters in which they eat and play.

Table 1.

Example of Current Ward Assignments

| Ward | N Children | Age Range | Ages of Most Children | Total N Caregivers | N Caregivers at One Timec | Children:Caregiver Ratio at One Timec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 (Intake) | 5 | 3–8 mos. | 6–7 mos. | 3 | 1 | 5:1 |

| #2 | 10 | 7 mos-5.9 yrs.a | 7–12 mos. | 3 | 1 | 10:1 |

| #3 | 10 | 1/3a4.6 yrs.a | 1–2 yrs. | 6 | 2 | 5:1 |

| #4 | 8 | 1.7–2.9 yrs. | 1–2+ yrs. | 6 | 2 | 4:1 |

| #5 | 12 | 2–7.7 yrs. | 2–3 yrs. | 6 | 2 | 6:1 |

| #6 (males) | 10 | 3–7 yrs. | 4 yrs. | 3 | 1 | 10:1 |

| #7(females) | 9 | 3.5–9+ yrs.a | 4–5 yrs. | 3 | 1 | 9:1 |

| #8(females) | 16 | 7–13 yrs.a | 9–10 yrs. | 3 | 1 | 16:1 |

|

| ||||||

| 8 Wards | N=80 | N=33+1=34b | N=11 | |||

Oldest child has special needs; two in #8: total of 5 special needs. Five children in #5 have behavioral control issues.

Caregivers work 24-hr, shifts, 8 am – 8 am, and off 48 hrs.; one extra caregiver works 8 am – 4 pm five days per week to take children to hospital.

“At one time” refers to the main daytime hours when all children are present on the ward.

A second type of information is staff schedules. This includes the number of hours caregivers work per day and days per week; the number of days off a staff person is allowed for sick days, vacation, maternity leave, and personal days; employment limitations such as transportation restrictions (e.g., caregivers do not want to come to work when it is dark because it is unsafe), availability and safety of public transportation; and any legislation or standards that guide or limit work hours. Also, what is the earliest time someone can start and the latest they could leave work safely, and how are substitutions for staff absences currently handled? All this information is needed to plan new staffing patterns to provide children with fewer different caregivers who are more consistently available to them, and such circumstances and staffing patterns are likely to be unique to each institution.

Step 6: Children's Schedules

It is necessary to have a description of the typical daily schedule, such as wakeup time, meal time, bath time, nap time, hours at school, free play, bedtime, and other scheduled activities for a typical day. This helps to determine the hours of the day that need to be covered, with more staff needed during the busier parts of the day and fewer when children are sleeping at night, for example.

Step 7: Integration by Age and Disability

To prepare groups of children that are integrated by age and disability, it is necessary to know how many children currently in the orphanage are of which ages, an example of which is presented in Table 2 for the groups in Table 1. This age distribution helps planners determine how many children of each age should be assigned to how many different groups. In addition to age, gender, and disability diversity, groups might be formed with other priorities, such as 1) keeping siblings together, 2) children who are especially attached to any given caregiver, and 3) children who are especially close to another child.

Table 2.

Frequency Distribution of Ages of Children

| Children's Ages | Frequency | Distribution to 8 Groups |

|---|---|---|

| 0 – 6 mos. |

|

each go to separate group |

| 6 – 12 mos. |

|

1 to 5 groups, 2 to 3 groups 1 to each group 1 to 5 groups, 2 to 3 groups 1 to 5 groups, 2 to 3 groups 2 to 6 groups, 1 to 2 groups + special 1 to 7 grps, 1 to 1 grp. + special needs |

| 12 – 18 mos. |

|

|

| 18 – 24 mos. |

|

|

| 24 – 36 mos. |

|

|

| 3 – 5 yrs. |

|

|

| 5 + yrs. |

|

|

N= 64 including special needs plus 16 children who will remain in #8.

Integrated groups may be greeted with more uncertainty and resistance than other structural changes, because simultaneously dealing with children of different ages and some with disabilities initially may appear overwhelming to caregivers who are accustomed to children who are all the same age simultaneously participating in each daily activity. Further, there may be concerns about older children being aggressive and harming younger children, especially infants, and about sexual activities. These may be real concerns and may need to be dealt with by initially integrating only up to certain ages and subsequently integrating by attrition as children naturally grow older or leave and are replaced with newly arrived infants.

Step 8: Planning Ward Assignments and Staff Schedules

With the above information in hand, senior staff need to plan ward assignments of children and new staff schedules. A staffing pattern must be designed so there are enough staff to cover 24 hours, seven days a week, and that these hours comply with the minimum and maximum amount allowable by any legislation or policy. More staff should be available during children's waking time when they are present in the institution whereas fewer staff are needed when children are sleeping or at school. Mainly, fewer different staff should be assigned to individual groups of children than they currently experience, and the same individuals should work with the same group of children consistently over time. This frequently requires staff to work more days per week but fewer hours per day than the common 24-hour shifts followed by several days off. Caregivers may find this objectionable, because it increases their costs for transportation and reduces their opportunities for time with their own families or to hold another job, so additional compensation may be necessary.

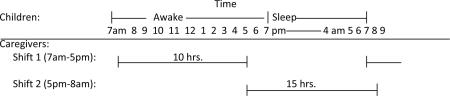

This planning phase can be complex, take considerable creativity, require some compromises, and be unique to each institution. For example, Tables 3 and 4 present two different examples of new staff schedules. Table 3 was designed for the orphanage providing the data in Tables 1 and 2. In this case, the goal was to have only four different caregivers per ward with the Floater working in two different wards; caregivers would work 40 hours per week. Table 4 gives another plan for a different orphanage both before and after staffing changes. This plan emphasized two primary caregivers who worked 5 days per week for 40 hours per week, did not change other staff that wanted 24-hour shifts, but eliminated two part-time positions.

Table 3.

Example of Staff Schedules

| Day of Month (One Group) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ------ | |

| Cgr. A | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | ------ |

| Cgr. B | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | ------ |

| Cgr. C | X | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | ------ |

| Cgr. F | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | X | 1 | 2 | -- | ------ | |||||||||

1 = Shift 1, 2 = Shift 2, X = off all day,--works shift am hours that day and off remainder of day.

For Cgr. A, B, C: Works Shift 1 (7am–5pm); next day works Shift 2 (5pm–8am next day); then next day off; and so on. Cgr. F (Floater) is shared with two wards.

Table 4.

Example of Schedule of Caregiver Work in a Group of 12–14 Children Before Staffing Changes (Top) and a Subgroup of 5–7 Children After Staffing Changes (Bottom)

| Before Staffing Changes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Hours Worked | |||||||

| Caregiver | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| a | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||||

| b | 14 | 14 | |||||

| c | 14 | 14 | |||||

| d | 24 | 24 | |||||

| e | 24 | 24 | |||||

| f | 24 | 24 | |||||

| g | 24 | ||||||

| h | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| i | 10 | 10 | |||||

| After Staffing Changes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Work Hours | |||||||

| Caregiver | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

| Primary a | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 12 | ||

| Primary b | 7 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 7 | ||

| Secondary c | 24 | 24 | |||||

| Secondary d | 24 | 24 | |||||

| Secondary e | 24 | 24 | |||||

| Secondary f | 24 | ||||||

|

|

|||||||

Step 9: Involving Staff

The same kind of activities described in Step 2 need to be conducted with line staff, whose enthusiasm and commitment is also required to implement changes successfully. These activities may be conducted earlier in the process, but sometimes it helps for senior staff to have clearly defined their goals and to have developed substantial commitment to them before engaging the staff. But line staff also need to participate in the planning and not feel these changes are being “totally forced on them.” So there should be meetings of staff similar to those described above with ample opportunity for questions and answers. Ultimately, however, it needs to be clear to staff that the director and senior staff are committed to implementing these changes, and when staff are uncertain or resistant, senior staff need to invoke “let's give it a try.”

Step 10: Implementation

The sequence of the tasks and activities to actually enact such major changes is very important. First, if there are any administrative issues to be resolved, such as approval of staff schedules by government institutions or administrative units, these need to be accomplished before a staff scheduling plan can be implemented.

Steps in actually enacting the previously described plans include:

The staff scheduling plan should be reviewed with the staff so they know what changes will take place in their work and personal lives. Some staff may not want to or cannot work the new schedule, and the director needs to be prepared to reassign or even replace such staff.

An inventory of the environmental needs must be composed and include any remodeling as well as new furniture, additional equipment, different or additional toys, and other materials that will be needed, especially if group size is to be reduced thus producing more groups to equip.

A minimum of two caregiver training sessions pertaining specifically to implementation should be conducted. The first meeting should include any details that are known at the time, philosophy to back up the need for changing schedules and integrating children, and discussion of future training sessions so that all staff members are prepared for the age, gender, and disability integration. The agenda for the second session is to answer any questions that may have developed and to resolve any problems. Caregivers often raise real problems that were unanticipated, such concerns need to be treated with respect, and often other caregivers will propose workable solutions. Caregivers also are often concerned about how they are going to handle age and disability integration. In our experience, while they will no longer have 2 and 3 hours with nothing to do except record keeping while children nap, neither will they have to feed 12 or 15 infants in an hour. It turns out to be easier to feed 2 or 3 infants while older children play, and to play with older children while infants sleep. Contrary to caregivers' initial expectations, the result is that caregivers are less harried and stressed than under the old system. Further, training should include techniques on how to position, handle, and relate to children with disabilities, if they are housed in the same orphanage and will be integrated into groups.

Consultants should meet with the directors and senior staff so that they are comfortable with all of the next steps and feel the consultants will support and assist them in the implementation process.

Children must be prepared psychologically and physically for the changes that will take place. They may want to visit the new ward, get to know the new staff people by visiting them in their current places, know which children are going to go with them, and older and younger children may visit each other so they can see the wards from which they will come to the new integrated group.

Near to moving day, each ward should begin to be set up so that age appropriate items are placed in a way to provide an efficient, but homey, environment. This initial set up should be described as temporary, so that once the children and staff move in they may feel free to change it to be more comfortable and efficient consistent with health and safety issues.

On moving day, there needs to be a schedule of what will be moved first. All remodeling should be completed unless there are things that can be done while the groups are residing in the ward. There may be “treat stations,” music, and other things to create a pleasant, upbeat atmosphere. All furniture, toys, equipment, and the children should be coded so that they match the new ward to which they are assigned. Coding could be done with colors (e.g., red tags for the “red ward”), numbers, animals, or whatever way appeals to the children and caregivers.

Staff should start on their new work schedules on moving day so that the needs of the new groupings can be accomplished with the appropriate number of adults.

These changes and especially moving day may seem overwhelming, and there can be a tendency for directors and senior staff to want to implement one change at a time, such as changing staff schedules first, implementing integration progressively over a period of time by attrition and replacement, etc. Such a strategy may be workable.

However, directors and senior staff may also want to implement all the changes but only in a few wards at a time. They may feel some staff members are more receptive to the changes than others, and that it would be best to ask for volunteers to be the first to participate in changes. We discourage this strategy. If there is uneven commitment to the changes, implementing them on a few wards especially with volunteers will only exacerbate the schism between those staff members who are in favor and those who are against the changes. Transitions, even very positive ones, are typically stressful, and as long as there is an option not to change, there is refuge for those who resist—“let's all give this a try.”

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F. Earlier is better: A meta-analysis of 70 years of intervention improving cognitive development in institutionalized children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2008;73:279–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2008.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. 2nd ed. Basic Books; New York, NY: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bradekamp S, Copple C. Developmentally appropriate practices in early childhood programs. rev. ed. NAEYC; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrova-Krol NA, Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F. Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on physical and cognitive development of children in Ukraine. Child Development. 2010;81(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature; University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; Tampa, FL. 2005. FMHI Publication #231. [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB. Integrating developmental scholarship into practice and policy. In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, editors. Developmental psychology: An advanced textbook. 5thEdition Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 570–601. [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB. Community-based interventions and services. In: Rutter M, et al., editors. Rutter's child and adolescent psychiatry. 5thedition Blackwell Publishing; London: 2008. pp. 971–988. [Google Scholar]

- Groark CJ, McCall RB, Li J. Unpublished manuscript, authors. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh PA: 2010. Characterizing the status and progress of a country's child welfare reform. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar M. Effects of early deprivation: Findings from orphanage-reared infants and children. In: Nelson CA, Luciana M, editors. Handbook of developmental cognitive neuroscience. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2001. pp. 617–629. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges J, Tizard B. IQ and behavioral adjustment of ex-institutional adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1989;30:53–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch . Human Rights Watch world report 1999. Human Rights Watch; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Julian M. Adult outcomes of early institutionalization. University of Pittsburgh; Pittsburgh, PA: 2009. Unpublished manuscript, author. [Google Scholar]

- Julian M, McCall RB. The development of children within different alternative residential care environments. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh, PA: 2010. Unpublished manuscript, authors. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley S. Regulatable factors in early childhood services. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Briefing Paper. Pittsburgh, PA: Sept., 1999. [Google Scholar]

- W. K. Kellogg Foundation . W. K. Kellogg Foundation logic model development guide. W. K. Kellogg Foundation; Battle Creek, MI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean K. The impact of institutionalization on child development. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:853–884. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish L, Harkins D, Serrano G, Gordon K. A social-emotional intervention in a Latin American Orphanage. Infant Mental Health Journal. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20270. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Groark CJ, Fish L, The Whole Child International Team Characteristics of environments, caregivers, and children in three Central American orphanages. Infant Mental Health Journal. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20292. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK. Children without permanent parental care: Research, practice, and policy. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh, PA: 2010. Unpublished manuscript, authors. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RS, Moore DN. Better late than early. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Muhamedrahimov RJ. New attitudes: Infant care facilities in St. Petersburg, Russia. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH handbook of infant mental health. Vol. 1. Perspectives on infant mental health. Wiley; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 245–294. [Google Scholar]; Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science. 2007;318:1934–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.1143921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas J, McCall RB. Characteristics of institutions, interventions, and resident children's development. University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development; Pittsburgh, PA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team Characteristics of children, caregivers, and orphanages for young children in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology: Special Issue on Child Abandonment. 2005;26:477–506. [Google Scholar]

- The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young orphanage children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2008;73 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2008.00483.x. Serial No. 291(3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F. Plasticity of growth in height, weight and head circumference: Meta-analytic evidence for massive catch-up after international adoption. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(4):334–343. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811320aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Luijk M, Juffer F. IQ of children growing up in children's homes: A meta-analysis on IQ delays in orphanages. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly – Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2008;54:341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, van IJzendoorn MH, Steele H, Kontopoulou A, Sarafidou Y. Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:1208–1220. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flospohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, Blackman M, Dunville R, Saul J. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The Interactive Systems Framework for Dissemination and Implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project Care Group Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child Development. 2005;76(5):1015–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]