Abstract

Background

Several recent studies have suggested that oestrogen exposure may increase the risk of prostate cancer (PCa).

Objectives

To examine associations between PCa incidence and mortality and population-based use of oral contraceptives (OCs). It was hypothesised that OC by-products may cause environmental contamination, leading to an increased low level oestrogen exposure and therefore higher PCa incidence and mortality.

Methods

The hypothesis was tested in an ecological study. Data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer were used to retrieve age-standardised rates of prostate cancer in 2007, and data from the United Nations World Contraceptive Use 2007 report were used to retrieve data on contraceptive use. A Pearson correlation and multivariable linear regression were used to associate the percentage of women using OCs, intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers to the age standardised prostate cancer incidence and mortality. These analyses were performed by individual nations and by continents worldwide.

Results

OC use was significantly associated with prostate cancer incidence and mortality in the individual nations worldwide (r=0.61 and r=0.53, respectively; p<0.05 for all). PCa incidence was also associated with OC use in Europe (r=0.545, p<0.05) and by continent (r=0.522, p<0.05). All other forms of contraceptives (ie, intra-uterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers) were not correlated with prostate cancer incidence or mortality. On multivariable analysis the correlation with OC was independent of a nation's wealth.

Conclusion

A significant association between OCs and PCa has been shown. It is hypothesised that the OC effect may be mediated through environmental oestrogen levels; this novel concept is worth further investigation.

Article summary

Article focus

Several recent studies have suggested that oestrogen exposure may increase the risk of prostate cancer (PCa).

Associations between PCa incidence and mortality and population-based use of oral contraceptives (OCs) have been examined.

It is hypothesised that OC by-products may cause an environmental contamination, leading to an increased low level oestrogen exposure and therefore higher PCa incidence and mortality.

Key messages

In this hypothesis generating ecological study, a significant association between female use of OCs and prostate cancer has been demonstrated.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study is an ecological study and thus has significant limitations with respect to causal inference. It must be considered hypothesis generating, and thought provoking.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common male malignancy in the Western world, and risk factors associated with this cancer remain ill defined.1 The only acknowledged risk factors thus far are: age, ethnicity and family history.1 Several studies have suggested that oestrogen exposure may increase the risk of prostate cancer,2–4 while other studies have not found an association.5 6

The use of oral contraceptives (OCs) has exploded over the past 40 years and has had a patchy uptake in terms of global utilisation. Emerging literature suggests that OC use may be associated with a variety of medical conditions among consumers, such as atheroembolic disease and even breast cancer.7–10 Aside from disease risk among actual drug consumers, there is also increasing concern about environmental contamination by endocrine disruptive compounds (EDCs) and their association with diseases of increasing incidence such as breast cancer (men and women), early onset puberty and testicular cancer. EDCs include a variety of compounds used in commercial applications, such as detergents, pesticides, cosmetics and building materials.11 It is plausible that by-products of OC metabolism could be passed via urine into the environment in general or drinking water, thus exposing the population at large.

In this report we examine associations between prostate cancer incidence and mortality and population-based use of OCs. In addition, to explore the specific effect of OCs, we also examined these outcomes in association with other modes of contraception.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This study utilised a geographic or ecological design to identify associations between aggregate use of contraception and rates of prostate cancer. We utilised data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer to retrieve age-standardised rates of country-specific prostate cancer incidence and mortality in 2008.12 The incidence data are derived from population-based cancer registries. These mostly cover entire national populations but may cover smaller, subnational areas, and, particularly in developing countries, only major cities. While the quality of information from most of the developing countries might not be of sufficient quality, this information is often the only relatively unbiaised source of information available on the profile of cancer in these countries.

The United Nations World Contraceptive Use 2007 report13 was used to retrieve data on contraceptive use. In this report, data were obtained from surveys of nationally representative samples of women of reproductive age. The estimates for each nation represent weighted averages derived for each country by the estimated number of women aged 15–49 in 2007 who are married or in union. These estimates are based on data on the proportion of women married or in union in each country contained in the World Marriage Database 200614 and on estimates of the number of women by age group obtained from World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision.15 Again information may be less accurate for developing countries; however, this is the best available information on contraceptive use.

The following information was collected: percentage of woman of reproductive age using OCs, intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers. The rationale for examining alternate uses of birth control was to examine specificity for OCs, as it is plausible that this measure is a marker of sexual activity, which itself has demonstrated some inconsistent association with prostate cancer.16 In addition to global incidence and mortality, we also examined continent specific and Europe specific outcomes as we wanted to test this association among a more homogenous group with narrower ranges of both OC use and prostate cancer incidence/mortality.

We also used data from The World Factbook (ISSN 1553-8133; also known as the CIA World Factbook) to retrieve information on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in each country.17 GDP refers to the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given period. GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of a country's standard of living. We used this data to control for prostate cancer screening tendencies since countries with a higher GDP are more prone to PCa screening.

The World Factbook is prepared by the CIA for the use of US government officials. However, it is frequently used as a resource for academic research papers.

Statistical analysis

Pearson correlation was used to associate age-adjusted prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates to the percentage of women using OCs, intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers. We performed these analyses by individual nations and by continents worldwide. We randomly identified 87 different nations for the survey, ensuring sampling of each continent (the list of countries included in the analysis can be found in appendix 1). We used 50% of countries available from each continent (25 of 50 in Africa, 25 of 50 in Asia, 24 of 47 in Europe, and 11 of 23 in America, Australia and New Zealand were also included). We did not use all available countries since we aimed at a equal representation of developed and under-developed countries (using the entire sample would have caused over-representation of under-developed countries and may have biased our results).

We performed a linear regression model to assess whether mode of contraceptive use is associated with prostate cancer incidence; mortality variables included in our model were: percentage of women of reproductive age using OCs, intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers; and GDP per-capita in each nation. Probability values <0.05 were deemed significant.

Results

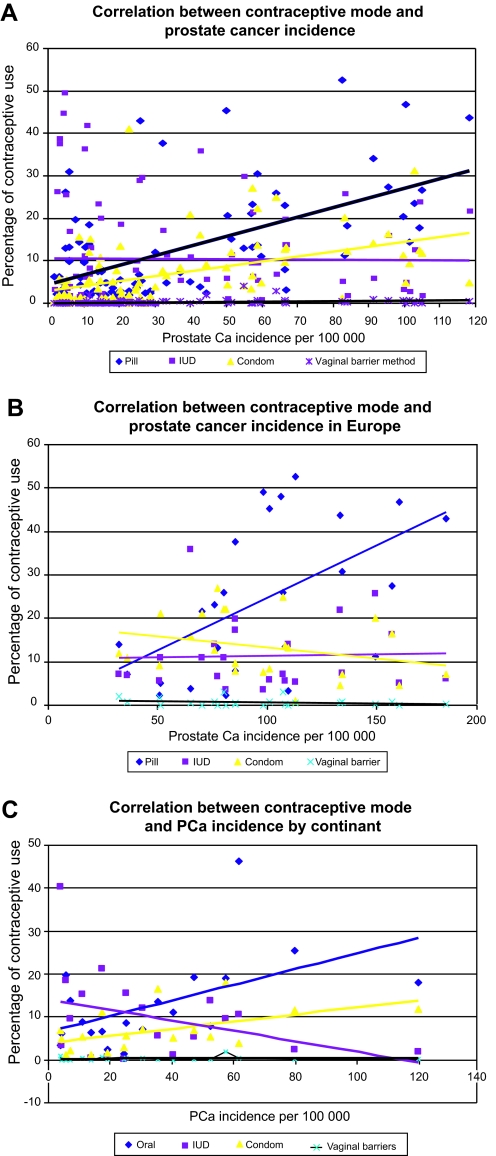

As shown in figure 1A–C, OC use was significantly correlated with prostate cancer incidence in the individual nations worldwide (figure 1A; r=0.61, p<0.05), in Europe (figure 1B; r=0.545, p<0.05), and by continent (figure 1C; r=0.522, p<0.05). All other forms of contraceptives (ie, intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers) were not correlated with prostate cancer incidence.

Figure 1.

Correlation between prostate cancer (PCa) incidence expressed as age standardised per 100 000 persons and percentage of contraceptive use in women aged 15–49, in individual nations: worldwide (A), in Europe (B), and by continent (C).

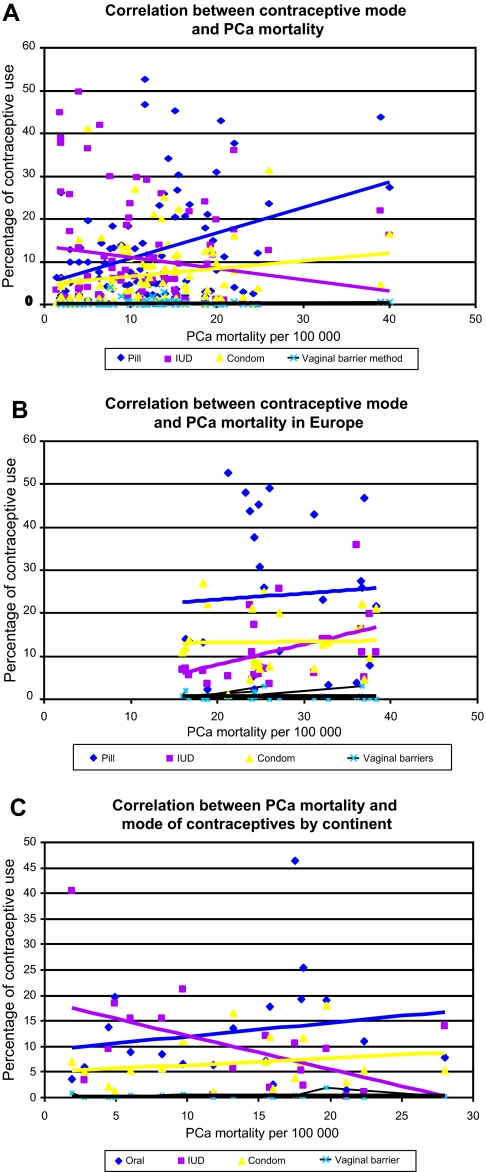

Mortality correlated with OC use in the individual nations worldwide (figure 2A; r=0.53, p<0.05). However, no correlation was found in prostate cancer mortality rates within Europe or by continent. In addition we did not demonstrate any correlation between other modes of contraceptives and prostate mortality rates.

Figure 2.

Correlation between prostate cancer (PCa) mortality expressed as age standardised per 100 000 persons and percentage of contraceptive use in women aged 15–49, in individual nations: worldwide (A), in Europe (B), and by continent (C). IUD, intrauterine device.

Table 1 shows the multivariable analysis of the association of PCa incidence and mortality with mode of contraceptives controlling for GDP per-capita. As shown, both incidence and mortality were associated with OC use even after controlling for an indicator of a country's wealth (adjusted estimate 1.06 (95% CI 0.58 to 1.6) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.1), for incidence and mortality respectively; p<0.01 for all).

Table 1.

Multivariable linear regression of the association of mode of contraception and GDP (a measure of country's wealth) with prostate cancer (PCa) incidence and PCa mortality

| Estimate | 95% CI | p Value | |

| PCa incidence | |||

| Oral contraceptive use | 1.06 | 0.58 to 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Intrauterine device | 0.01 | −0.4 to 0.4 | 0.9 |

| Condom use | 0.9 | −0.1 to 1.9 | 0.3 |

| Vaginal barrier | 0.07 | −4 to 10 | 0.5 |

| GDP | 0.6 | 0.1 to 1.1 | 0.055 |

| PCa mortality | |||

| Oral contraceptive use | 0.75 | 0.31 to 1.1 | 0.06 |

| Intrauterine device | −0.02 | −0.4 to 3 | 0.2 |

| Condom use | 0.2 | −0.1 to 0.329 | 0.3 |

| Vaginal barrier | 0.01 | −2.1 to 2 | 0.9 |

| GDP | 0.16 | 0.04 to 0.9 | 0.09 |

GDP, gross domestic product per capita. GDP refers to the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given period. GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of a country's standard of living.

Discussion

In this study we have shown a strong correlation between the country-specific female OC use and incidence of prostate cancer among worldwide, continent and even intra-European nations. This correlation appeared specific to OC as no association was demonstrated with other forms of contraception such as intrauterine devices, condoms or vaginal barriers. Furthermore, prostate cancer mortality was also associated with OC use when examined globally. The correlation to OC use was independent of GDP as a measure of a country's wealth, and strongest in Europe.

This study represents the first systematic analysis of associations between OC use and prostate cancer. It is an ecological study and thus has, as with all correlational studies, significant limitations with respect to causal inference.18 As such, it must be considered hypothesis generating.

There are several plausible explanations for this association. Prostate cancer has been associated with sexual transmission. Although no particular infectious agent has been identified, recent interest in the xenotropic murine leukaemia virus-related virus and its discovery in semen has raised this as a possible candidate.17 19 Clearly more studies are needed. We would hypothesise, however, that if sexual activity were the explanation for the above observations, similar outcomes would be noted for other forms of contraception and that one could even assume a protective effect. As we do not have individual level data, these hypotheses are not testable and would require a long latency period.

Another plausible explanation for the association between OC use and prostate cancer is the potential environmental impact of OCs. The last two decades have witnessed growing scientific concerns and public debate over the potential adverse effects that may result from exposure to a group of chemicals that have the potential to alter the normal functioning of the endocrine system in wildlife and humans. These chemicals are typically known as endocrine disturbing compounds (EDCs). Temporal increases in the incidence of certain cancers (breast, endometrial, thyroid, testis and prostate) in hormonally sensitive tissues in many parts of the industrialised world are often cited as evidence that widespread exposure of the general population to EDCs has had adverse impacts on human health. OCs in use today can potentially act as EDCs as they frequently contain high doses of ethinyloestradiol, which is excreted in urine without degradation. This can then end up either in the drinking water supply or passed up the food chain.11 OCs were made publicly available in the 1960s, and have been widely used since the 1980s, hence the exposure to these substances, even in small quantities, may be chronic enough (20–30 years) to have a clinically significant effect.

There are limited epidemiological data that have examined associations between prostate cancer and exposure to environmental EDCs. These are largely derived from occupational exposures, and many lack internal exposure information. In one retrospective cohort epidemiology study of Canadian farmers linked to the Canadian National Mortality Database, a weak but statistically significant association between acres sprayed with herbicides and prostate cancer deaths was found.20 Multigner et al21 have recently demonstrated that environmental exposure to chlordecone, an organochlorine insecticide with well defined oestrogenic properties, increases the risk of prostate cancer. Studies on workers in Germany22 and the USA23 showed a small but statistically significant excess in prostate cancer mortality, based on a limited number of cases. Other studies have failed to demonstrate this association.24–26 All former studies looked at occupation exposure to high concentrations in pesticides; however, in our study we speculate that low concentrations in drinking water supply may cause PCa, due to the more chronic everyday exposure. Furthermore, environmental EDCs may affect the unborn child in the state of organogenesis and cause significant genetic or epigenetic malformations.

In contrast, several recent studies have demonstrated that PCa may not be related to endogenous androgens. The Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group, analysing5 18 prospective studies of 3886 men with PCa and 6438 control subjects, found no associations between PCa risk and serum concentrations of testosterone, calculated free testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, androstenedione, androstanediol glucuronide, oestradiol or calculated free oestradiol. However, this study investigated serum hormonal levels. EDCs may increase the risk of PCa by affecting tissue levels or causing genetic or epigenetic changes that may not be found using serum levels. Li Tang et al6 studied the association between repeat polymorphisms of three key oestrogen-related genes (CYP11A1, CYP19A1, UGT1A1) and risk of prostate cancer in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. The results indicate that repeat polymorphisms in genes involved in oestrogen biosynthesis and metabolism may influence risk of PCa. Further studies are needed to determine the role of EDCs in PCa.

Some may argue that our results only reflect screening and treatment patterns for prostate cancer, with the more developed countries having both a higher use of OCs and a higher incidence of prostate cancer. Unfortunately data on worldwide screening tendencies or prostate specific antigen (PSA) use is unavailable. However, we included a multivariable analysis controlling for GDP per capita. GDP refers to the market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a given period. GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of a country's standard of living. In our multivariable analysis, OC use was associated with both incidence and mortality, even when controlling for GDP. We believe this analysis has strengthened our hypothesis considerably; however, additional confounding does exist and should be explored in future studies. Finally, we cannot report the true levels of EDCs in the water supply and food chain. We hope such data will be available in the near future.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a significant correlation between OC use and prostate cancer incidence and mortality. Classic case–control and cohort studies may not reveal this association as we are hypothesising an environmental effect. Tissue correlation and environmental studies are encouraged.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1

A. List of countries included in analysis

Kenya

Mozambique

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

Angola

Cameroon

Central African Republic

Chad

Congo

Gabon

Egypt

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

Sudan

Botswana

Namibia

South Africa

Benin

Ghana

Mali

Mauritania

Niger

Nigeria

Senegal

Sierra Leone

Togo

China

Japan

Republic of Korea

Afghanistan

Bangladesh

India

Iran (Islamic Republic of)

Kazakhstan

Pakistan

Tajikistan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Indonesia

Myanmar

Philippines

Thailand

Viet Nam

Israel

Jordan

Lebanon

Oman

Saudi Arabia

Syrian Arab Republic

Turkey

Yemen

Belarus

Czech Republic

Hungary

Poland

Romania

Russian Federation

Slovakia

Ukraine

Estonia

Finland

Latvia

Lithuania

Norway

Sweden

United Kingdom

Albania

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Italy

Portugal

Spain

Belgium

France

Germany

Switzerland

Mexico

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Chile

Paraguay

Peru

Uruguay

Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of)

Canada

United States of America

Australia

New Zealand

B. List of Continent analysed

Eastern Africa

Middle Africa

Northern Africa

Southern Africa

Western Africa

Eastern Asia

South-Central Asia

South-Eastern Asia

Western Asia

Eastern Europe

Northern Europe

Southern Europe

Western Europe

Caribbean

Central America

South America

Northern America

Australia/New Zealand

Footnotes

To cite: Margel D, Fleshner NE. Oral contraceptive use is associated with prostate cancer: an ecological study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000311. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000311

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: Both authors have directly participated in the planning, execution or analysis of the study, and have read and approved the final version submitted.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data is available from the corresponding author at: sdmargel@gmail.com

References

- 1.Damber JE, Aus G. Prostate cancer. Lancet 2008;371:1710–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosland MC. The role of steroid hormones in prostate carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2000;27:39–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platz EA, Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of sex steroid hormones and their signaling and metabolic pathways in the etiology of prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004;92:237–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leav I, Lau KM, Adams JY, et al. Comparative studies of the estrogen receptors beta and alpha and the androgen receptor in normal human prostate glands, dysplasia, and in primary and metastatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol 2001;159:79–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, et al. ; Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:170–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang L, Yao S, Till C, et al. Repeat polymorphisms in estrogen metabolism genes and prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. Carcinogenesis 2011;32:1500–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farmer RD, Lawrenson RA, Thompson CR, et al. Population-based study of risk of venous thromboembolism associated with various oral contraceptives. Lancet 1997;349:83–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White E, Malone KE, Weiss NS, et al. Breast cancer among young U.S. women in relation to oral contraceptive use. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994;86:505–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellem SJ, Wang H, Poutanen M, et al. Increased endogenous estrogen synthesis leads to the sequential induction of prostatic inflammation (prostatitis) and prostatic pre-malignancy. Am J Pathol 2009;175:1187–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellem SJ, Risbridger GP. Aromatase and regulating the estrogen:androgen ratio in the prostate gland. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;118:246–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The United Nations World Water Development Report. http://www.unesco.org/water/wwap/wwdr/index.shtml

- 12.GLOBOCAN Prostate Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide in 2008. http://globocan.iarc.fr/factsheets/cancers/prostate.asp [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations World Contraceptive Use, 2007. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/contraceptive2007/WallChart_WCU2007_Data.xls

- 14.World Marriage Data 2006. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/worldfertility2007/UNPD_Mar_2006_OrderForm_Documentation.pdf

- 15.World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2006/wpp2006.htm

- 16.Schlaberg R, Choe DJ, Brown KR, et al. XMRV is present in malignant prostatic epithelium and is associated with prostate cancer, especially high-grade tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:16351–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.List of countries by GDP (nominal) per capita. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)_per_capita

- 18.Morgenstern H. Ecologic studies in epidemiology: concepts, principles, and methods. Annu Rev Public Health 1995;16:61–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong S, Klein EA, Das Gupta J, et al. Fibrils of prostatic acid phosphatase fragments boost infections with XMRV (xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus), a human retrovirus associated with prostate cancer. J Virol 2009;83:6995–7003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison H, Savitz D, Semenciw R, et al. Farming and prostate cancer mortality. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:270–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Multigner L, Ndong JR, Giusti A, et al. Chlordecone exposure and risk of prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;28:3457–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becher H, Flesch-Janys D, Kaupinen T, et al. Cancer mortality in German male workers exposed to phenoxy herbicides and dioxins. Cancer Causes Control 1996;7:312–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fingerhut MA, Halperin WE, Marlow DA, et al. Cancer mortality in workers exposed to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. New Engl J Med 1991;324:212–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertazzi PA, Riboldi L, Pesatori A, et al. Cancer mortality of capacitor manufactoring workers. Am J Ind Med 1987;11:165–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown DP. Mortality of workers exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls—an update. Arch Environ Health 1987;42:333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinks T, Steele G, Smith AB, et al. Mortality among workers exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Am J Epidemiol 1992;136:389–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.