Abstract

Background

Trauma patients are characterised by alterations in the immune system, increased exposure to infectious complications, sepsis and potentially organ failure and death. Glutamine supplementation to parenteral nutrition has been proven to be associated with improved clinical outcomes. However, glutamine supplementation in patients receiving enteral nutrition and its best route are still controversial. Previous trials have been limited by a small sample size, use of surrogate outcomes or a limited period of supplementation. The aim of this trial is to investigate if intravenous glutamine supplementation to trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition is associated with improved clinical outcomes in terms of decreased organ dysfunction, infectious complications and other secondary outcomes.

Methods/design

Eighty-eight critically ill patients with multiple trauma receiving enteral nutrition will be recruited in this prospective, triple-blind, block-randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial to receive either 0.5 g/kg/day intravenous undiluted alanyl-glutamine or intravenous placebo by continuous infusion (24 h/day). Both groups will be receiving the same standard enteral nutrition protocol and the same standard intensive care unit care. Supplementation will continue until discharge from the intensive care unit, death or a maximum duration of 3 weeks. The primary outcome will be organ-dysfunction evaluation assessed by the pattern of change in sequential organ failure assessment score over a 10-day period. The secondary outcomes are: the changes in total sequential organ failure assessment score on the last day of treatment, infectious complications during the ICU stay, 60-day mortality, length of stay in the intensive care unit and body-composition analysis.

Discussion

This study is the first trial to investigate the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on reducing severity of organ failure and infectious complications and preservation of lean body mass.

Trial registration number

This trial is registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. NCT01240291.

Article summary

Article focus

Glutamine supplementation has demonstrated improved clinical outcomes in patients receiving parenteral nutrition. However, its effect and the best route of administration remain inconclusive for patients receiving enteral nutrition.

Previous trials for patients receiving enteral nutrition had a number of limitations.

Key messages

This proposed research with other worldwide trials will have implications in improving the practice of glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients.

The results of this trial will provide pilot data for a large multicentre trial to investigate the effect of intravenous glutamine supplementation in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on infectious complications and mortality.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first trial to investigate the effect of intravenous glutamine supplementation in trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on organ failure, infectious complications and body composition.

Supplementation is continued as long as the patient is in the intensive care unit or to a maximum duration of 21 days.

This is a single-centre trial, so it is not powered to investigate the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation on mortality.

Data will not be applicable to trauma patients with severe renal failure or hepatic impairment.

The long-term outcomes (eg, 6-month mortality) are not assessed.

Background

Multiple trauma is life-threatening, not only from the initial trauma insult alone, but also from the subsequent massive immunological dysfunctions and metabolic alterations.1 Multiple trauma is characterised by impairment in the immune response2 3 that is associated with an increased rate of infectious complications and death.4 5 In fact, infectious complications in critically ill patients remain a serious problem worldwide and are independently associated with higher hospital mortalities.6

Metabolic response to critical illness

Critical illness exhibits a metabolic response that is characterised by hypermetabolism,7 insulin resistance associated with hyperglycaemia,8 9 lipolysis10 and accelerated protein catabolism7 that might reach up to 2% per day.11 In critically ill patients, net protein catabolism is accelerated,12–16 despite vigorous nutritional support and increased protein intake.13 14 Loss of lean body mass during critical illness is considered a major clinical problem that delays wound healing and recovery. In parallel, there is a depletion of glutamine levels in muscle.11 16 Although glutamine production is increased in critically ill patients, it is not sufficient to maintain intracellular levels of glutamine in muscle.17

Glutamine supplementation

Glutamine, traditionally considered as a non-essential amino acid under normal physiological conditions, has received considerable attention in becoming ‘conditionally indispensable’ during catabolic states such as major surgery and critical illness.18 Under stress and catabolic conditions such as major surgery,19 burn injury20 21 and multiple trauma,22–25 there is a severe depletion of glutamine levels in plasma. It has been reported that a low plasma glutamine level at intensive-care unit (ICU) admission is an independent risk factor for mortality.26

In the past two decades, numerous trials have documented beneficial effects of glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients.23 27–35 There is good evidence that glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients receiving parenteral nutrition is associated with improved clinical outcomes in terms of improved survival rate, decreased infections, costs and reduced hospital length of stay.27–31 36 Indeed, currently glutamine supplemented parenteral nutrition is the standard of care in critical illness.37–39 However, there are also recent trials that failed to demonstrate any beneficial effect of supplemented total parenteral nutrition.40 41 It has been reported that intravenous glutamine supplementation in surgical patients counteracts muscle glutamine depletion and can enhance the rate of muscle protein synthesis.42 43 However, in critically ill patients, although intravenous glutamine supplementation increased plasma glutamine levels, muscle glutamine concentration and muscle protein synthesis were only marginally influenced.44 45 This might be explained by the increased demand on glutamine in critically ill patients.

Glutamine supplementation in patients receiving enteral nutrition and its best route are still debated. Despite the numerous numbers of clinical trials that have been conducted to investigate the beneficial effects of glutamine supplementation in patients receiving enteral nutrition,23 32–35 46–50 the results are conflicting and inconclusive. Enteral nutrition is advocated in critically ill and trauma patients when the gastrointestinal tract is functioning in terms of reduced infectious complications.51–53 Therefore, enteral glutamine supplementation is attractive when tube feeding is carried out.54 However, in clinical practice with enteral nutrition, especially in critically ill patients, there is a clear difference between what is targeted and what actually could be delivered.46 It has been documented that the systemic bioavailability of glutamine via the enteral route is less than via the intravenous route.55 To overcome the problem of not reaching the target dose by the enteral route, and the possibility of altered gut-absorption capacity, a number of trials investigated the effect of intravenous glutamine supplementation in patients receiving enteral nutrition.56–59 However, these trials were: pilot studies, including both enteral- and parenteral-nutrition-receiving patients, and most measured surrogate outcomes.

As primary outcomes in nutritional intervention trials, infectious complications and mortality require a large number of participants.60–62 Therefore, critical illness scores that relate to mortality and infectious morbidity end points have been considered as an alternative outcome measure.60 61 Multiple organ failure is considered as a reliable predictor of mortality in critically ill patients.63 Since mortality is not a feasible endpoint in a single-centre trial, we decided to use sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score as a surrogate primary outcome measure.

The aim of this study is to determine whether providing intravenous alanyl-glutamine (0.5 g/kg/day) will be associated with improved clinical outcomes in terms of reduced severity of organ dysfunction and reduction in infectious morbidity in mechanically ventilated trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on organ dysfunction and infectious morbidity. In addition, our study is the first clinical trial to investigate the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation on body composition in multiple trauma patients.

Research questions

What is the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation compared with placebo in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on organ dysfunction; Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA); (∆SOFA)?

What is the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation compared with placebo in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on infectious morbidity, 60-day mortality, length of stay in ICU, length of stay in hospital, number of days on mechanical ventilation, number of days of antibiotic use during ICU stay, and fat-free mass and fat percentage as a measure of body composition?

Methods/design

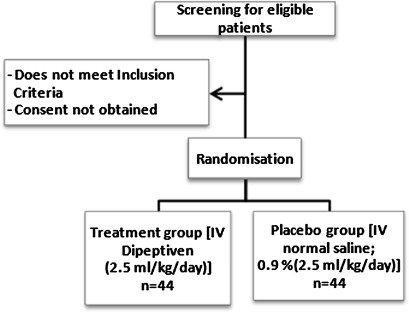

The GLutamine supplementation IN Trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition study protocol (GLINT) Study is a prospective, interventional, single-centre, concealed block-randomisation, triple-blinded (subject, care givers, outcome assessor), placebo-controlled trial (figure 1). The study has been designed with the Consolidated Standards for Reporting of Trials guidelines.64 The trial will be conducted in a tertiary university-affiliated intensive-care unit at Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital (RBWH), Brisbane, Australia. It has been approved by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (Project No 2010001359) and the Human Ethics Committee of RBWH (Protocol No HREC/10/QRBW/131). Dipeptiven is unregistered in Australia, so for the purpose of this trial, clinical trial notification (CTN) has been obtained from the Therapeutic Goods Administration of Australia (TGA) (trial no 2010/0623). The patients will be enrolled in the study after informed consent has been obtained from next of kin.

Figure 1.

Trial flow chart. IV, intravenous.

The duration of supplementation in many previous trials was short (eg, 3–7 days), which might explain why no effect has been found in many of them. In addition, it has been considered that a minimum of 5 days of glutamine supplementation is necessary to show an effect on infectious complications.23 Therefore, we decided to continue supplementation for a longer period of time (ie, 3 weeks) as long as the patient remained in the ICU. Also, the maximum approved dose (0.5 g/kg/day alanyl-glutamine) to ensure maximal beneficial effect will be given.

Selection of participants

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria are: age 18–85 years, patients admitted with a diagnosis of multiple trauma requiring mechanical ventilation, patients requiring enteral feeding for >48 h, expected length of stay in the ICU >48 h, functional access for enteral tube feeding and central access for administration of test solution, and negative β HCG (pregnancy test) in females (18–60 years).

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria are: pregnancy, age <18 years, significant hepatic failure (patients with Childs C Cirrhosis), severe renal failure (glomuerular filtration rate (eGFR) <50 ml/min), patients with inborn errors of amino-acid metabolism (eg, phenylketonurea), patients with metabolic acidosis (pH<7.35), not expected to be in the ICU >48 h (owing to imminent death), unable to tolerate enteral nutrition within 72 h, enrolment in other ICU intervention study if contraindicated, patients in whom parenteral nutrition is required from the outset or an absolute contraindication to enteral nutrition.

Randomisation

Participants will be randomised by opaque sealed envelope after enrolment. Numbers in the envelope have been generated by a computer-generated randomisation (http://www.randomization.com) table based on blocks of four to assign patients to treatment group or placebo group. The solutions will be prepared by the unblinded pharmacist (JR) and placed into identical infusion bags. The study solutions will be indistinguishable by colour, smell or taste.

Intervention

Intervention arm

This group (randomly allocated) will receive intravenous alanyl-glutamine (0.5 g/kg body weight/day; 2.5 ml/kg body weight; ie, 0.35 g l-glutamine/kg body weight/day; Dipeptiven, Fresenius-Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) by continuous infusion (24 h/day) through a dedicated lumen via central venous access until discharge from the ICU, death, or for a maximum duration of 3 weeks. Dipeptiven is a solution (20%, w/v) of glutamine-containing dipeptide, N(2)-l-alanyl-l-glutamine. The normal body weight will be calculated according to Broca's formula (normal body weight (kg)=patient height (cm)–100). This formula has been used by the ‘Reducing Deaths Due to Oxidative Stress’ study,65 and we elected to use it, as each patient's height can be accurately measured. This group represents the treatment group. It has been advised that for the intervention nutrient to have beneficial efficacy, it should be administered as soon as possible after the injury.66 Therefore, the intervention solution will be initiated within 24–48 h after admission to the ICU and independent from the start of enteral nutrition (ie, supplementation will be started even before enteral nutrition starts).

Control arm (placebo)

This group will receive intravenous placebo (normal saline; 0.9% NaCl; 2.5 ml/kg/day) by continuous infusion (24 h/day) through a dedicated lumen via central venous access until discharge from the ICU, death or for a maximum duration of 3 weeks.

All patients in both groups will receive standard, polymeric, high-caloric, high-protien enteral formula (1.2 kcal/1 ml; 12 g/l fibre; 55.5 g/l protein) and start at a rate of 40 ml/h according to the standard feeding protocol followed at RBWH.67 Enteral nutrition will be targeted to be initiated within 24–48 h, and the aim is to reach the target goal by day 3. If enteral nutrition has failed by day 3 post-ICU admission, parenteral nutrition will be started. It will not be initiated until all efforts to maximise enteral nutrition have been attempted, including motility agents and small-bowel feeding. If the subject continues to require enteral nutrition after 3 weeks or is discharged from the ICU, intravenous supplementation will be discontinued.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints

Outcome measures will be taken by a blinded investigator. The primary outcome measure will be taken daily until discharge from the ICU, death or maximum duration of 10 days.

The primary endpoint is organ dysfunction evaluation assessed by the pattern of change in SOFA score over a period of 10 days. This will be analysed by comparing daily measured SOFA score subtracted from the baseline SOFA score (the delta daily total SOFA score) each day and calculating the regression coefficients for each resulting slope. The regression coefficients for the two groups will be compared with a Student t test as described by Beal et al.60

Secondary endpoints

The secondary outcomes are:

The change in total SOFA score on the last day of treatment, where the change in total SOFA score=baseline total SOFA score–last day of treatment total SOFA score. A higher number indicates an improvement compared with baseline.

Infectious morbidity (ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary-tract infection, bloodstream infection, sinusitis, abdominal infection, sepsis) during the ICU stay or a maximum duration of 3 weeks. We will use standardised definitions to limit bias, so modified criteria of the Centre for Disease Control definitions will be followed.68

Sixty-day mortality.

Length of stay in the ICU.

Length of stay in hospital (if delayed discharge owing to placement problems, will record from the date the patient is regarded as fit for discharge by medical staff).

Number of ventilator-free days (VFD). A ventilator-free day is defined as a 24 h period from midnight to midnight that a patient is breathing independently of the ventilator. However, a day with tracheotomy cannula in place but without mechanical ventilation before extubation will be counted as a ventilator-free day.

Number of days of antibiotic use during the ICU stay.

Fat-free mass and fat percentage as a measure of body composition (bioelectric impedance spectroscopy (BIS)).69 BIS will be measured using a multifrequency, spectroscopy bioelectrical impedance analyser (ImpediMed SFB7, ImpediMed, Brisbane, Australia). This will be measured at baseline, and once weekly during the ICU stay or a maximum of 3 weeks. BIS relies on passing a small electric current through the body and measuring impedance (resistance) to the current. This is dependent on total body water and, in combination with information on weight, height and gender, allows an estimation of fat percentage and fat-free mass. In general, bioelectrical impedance analysis has been validated to be used as a tool for nutritional status assessment in critically ill patients,70 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and patients with acute respiratory failure,71 and can give a reasonable estimation of the change in body composition during an ICU day.

Routine ICU blood tests will be recorded daily until discharge from the ICU or a maximum duration of 3 weeks, including white-blood-cell count, platelets, nuetrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, urea, creatinine, protein and albumin. In 15 patients, C-reactive protein will be measured as a marker of inflammation and plasma amino acids profile will be measured and at baseline, day 7, day 14 and day 21.

Statistics

Sample-size calculation

Statistical analysis for the primary point (the delta daily total SOFA score plotted each day over 10 days) would involve linear regression power analysis where y=delta daily total SOFA score and x=day of measurement. Linear regression would therefore provide the slope of line, which is similar to the methodology used by Beale et al.60 Using assumptions about the primary endpoint, the analysis indicated that a sample size of 41 in each group is required to differentiate between the two groups with slopes similar to that reported by Beale et al,60 that is a change in slope from (−0.15) under the null hypothesis to (−0.30) under the alternative hypothesis when the SD of the mean is 3.00, the SD of the residuals is 1.00, and the two-sided significance level is 0.05. Allowing for dropouts, 88 patients will be recruited.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis will be performed using PASW software version 19.0 (SPSS). A baseline comparison of demographics, severity of illness and baseline measures will be carried out between each group, using a combination of Student t tests and χ2 tests. Dichotomous data (infectious complications, ICU mortality, and 60-day mortality) will be compared between groups using the χ2 test. Normally distributed continuous data will be analysed by a parametric test (ie, Student t test or ANOVA) and reported as mean±SD. Non-normally distributed continuous data will be analysed with an appropriate non-parametric test (eg, Mann–Whitney U test) and reported as median±IQR. Data will be analysed on the basis of intention-to-treat analysis (as per randomisation) and per protocol analysis for patients who receive at least 5 days' supplementation. The differences will be considered statistically significant at p<0.05. An intention-to-treat analysis using a carry-forward analysis for missing data will be performed for all participants including withdrawn patients.

Monitoring

Regular team meetings will be held. The principal investigator, coinvestigators and other researchers will review study progress at these meetings, address pertinent issues and identify further actions to be taken. The principal investigator will ensure via this regular review process that data are managed appropriately (ie, stored in ‘potentially reidentifiable’ fashion) and that appropriate steps are taken with regard to data cleansing and dissemination of results. Also, an independent Data Monitoring Committee will monitor patients' safety and treatment efficacy data while the trial is ongoing. This committee is independent of the sponsor and investigators, and has no competing interests.

Confidentiality and privacy

Participants will not be identified by name, and confidentiality of the information in the medical report will be preserved. The information on subjects will be stored in both paper copies, on computer and on a CD in a coded manner. The data will be stored in a locked filing cabinet in a locked office. The computer will be password-protected. The data will be stored for 15 years and disposed after this period in a confidential shredder.

Study termination

There is no plan for early trial termination. The study will be considered terminated upon completion of all patient treatments and evaluations. If an interim analysis is carried out, Bonferroni corrections will be applied in the final stage (ie, significance p<0.05 will be changed to p<0.025, which will require a doubling of the number of subjects). However, there is no plan to carry out any interim analyses.

Adverse events reporting

All serious adverse events (SAEs) that are thought to be related to treatment are subject to expedited reporting and will be reported within 24 h. The principal investigator will be responsible for follow-up of all SAEs to ensure all details are available. The principal investigator will be responsible for reporting to the regulatory authorities (Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia), the study supplement manufacturer (Fresenius Kabi), the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital Research Ethics Committee, and University of Queensland ethics committee all SAE events that occur in the study.

Discussion

This proposed trial with other worldwide trials will have implications in improving the practice of glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients. However, the results of this trial will only be relevant to trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition. It may not be directly applicable to other critically ill patients. The data for this study will not be applicable to trauma patients with severe renal failure or hepatic impairment. This trial is a single-centre trial, so it is not powered to investigate the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation on mortality. This study will not be assessing underlying immunological or inflammatory changes, so the exact mechanism of any beneficial effects will not be clearly understood. Long-term outcomes are not assessed in this trial.

However, this trial is the first to investigate the effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation in multiple trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition on organ dysfunction, infectious complications and body composition. We anticipate that the data from this study will add to the current practices of intravenous glutamine supplementation in trauma patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany for facilitating the provision of Dipeptiven. We thank S Adnan and J Varghese for assistance.

Footnotes

To cite: Al Balushi RM, Paratz JD, Cohen J, et al. Effect of intravenous GLutamine supplementation IN Trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition study protocol (GLINT Study): a prospective, blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000334. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000334

Funding: This trial is supported by a grant from Royal Brisbane Women's Hospital Foundation.

Competing interests: Fresenius Kabi has a non-commercial interest in the project. Fresenius Kabi and Royal Brisbane Women's Hospital foundation have no role in the protocol design and will not be involved in the analysis or interpretation of data.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Human Ethics Committee of Royal Brisbane Women's Hospital (protocol number: HREC/10/QRBW/131) and the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee (Project No 2010001359).

Contributors: RMA developed the study concept. RMA, JP, JC and MB developed the study design and protocol. JD provided statistical advice and will be involved in statistical consultation. JL provided advice and input to the study. JR will be coordinating the randomisation and preparation of study solutions. RMA drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Napolitano LM, Faist E, Wichmann MW, et al. Immune dysfunction in trauma. Surg Clin North Am 1999;79:1385–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Mahony JB, Palder SB, Wood JJ, et al. Depression of cellular immunity after multiple trauma in the absence of sepsis. J Trauma 1984;24:869–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faist E, Mewes A, Strasser T, et al. Alteration of monocyte function following major injury. Arch Surg 1988;123:287–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditschkowski M, Kreuzfelder E, Rebmann V, et al. HLA-DR expression and soluble HLA-DR levels in septic patients after trauma. Ann Surg 1999;229:246–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker CC, Oppenheimer L, Stephens B, et al. Epidemiology of trauma deaths. Am J Surg 1980;140:144–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 2009;302:2323–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monk DN, Plank LD, Franch-Arcas G, et al. Sequential changes in the metabolic response in critically injured patients during the first 25 days after blunt trauma. Ann Surg 1996;223:395–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Crit Care Clin 2001;17:107–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black PR, Brooks DC, Bessey PQ, et al. Mechanisms of insulin resistance following injury. Ann Surg 1982;196:420–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein S, Peters EJ, Shangraw RE, et al. Lipolytic response to metabolic stress in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 1991;19:776–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamrin L, Andersson K, Hultman E, et al. Longitudinal changes of biochemical parameters in muscle during critical illness. Metabolism 1997;46:756–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe RR, Jahoor F, Hartl WH. Protein and amino acid metabolism after injury. Diabetes Metab Rev 1989;5:149–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe RR, Goodenough RD, Burke JF, et al. Response of protein and urea kinetics in burn patients to different levels of protein intake. Ann Surg 1983;197:163–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streat SJ, Beddoe AH, Hill GL. Aggressive nutritional support does not prevent protein loss despite fat gain in septic intensive care patients. J Trauma 1987;27:262–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamrin L, Essen P, Forsberg AM, et al. A descriptive study of skeletal muscle metabolism in critically ill patients: free amino acids, energy-rich phosphates, protein, nucleic acids, fat, water, and electrolytes. Crit Care Med 1996;24:575–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson NC, Carroll PV, Russell-Jones DL, et al. The metabolic consequences of critical illness: acute effects on glutamine and protein metabolism. Am J Physiol 1999;276:E163–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mittendorfer B, Gore DC, Herndon DN, et al. Accelerated glutamine synthesis in critically ill patients cannot maintain normal intramuscular free glutamine concentration. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1999;23:243–50; discussion 50–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacey JM, Wilmore DW. Is glutamine a conditionally essential amino acid? Nutr Rev 1990;48:297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parry-Billings M, Baigrie RJ, Lamont PM, et al. Effects of major and minor surgery on plasma glutamine and cytokine levels. Arch Surg 1992;127:1237–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry-Billings M, Evans J, Calder PC, et al. Does glutamine contribute to immunosuppression after major burns? Lancet 1990;336:523–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore DC, Jahoor F. Glutamine kinetics in burn patients. Comparison with hormonally induced stress in volunteers. Arch Surg 1994;129:1318–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askanazi J, Carpentier YA, Michelsen CB, et al. Muscle and plasma amino acids following injury. Influence of intercurrent infection. Ann Surg 1980;192:78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houdijk AP, Rijnsburger ER, Jansen J, et al. Randomised trial of glutamine-enriched enteral nutrition on infectious morbidity in patients with multiple trauma. Lancet 1998;352:772–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weingartmann G, Oehler R, Derkits S, et al. HSP70 expression in granulocytes and lymphocytes of patients with polytrauma: comparison with plasma glutamine. Clin Nutr 1999;18:121–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boelens PG, Houdijk AP, Fonk JC, et al. Glutamine-enriched enteral nutrition increases HLA-DR expression on monocytes of trauma patients. J Nutr 2002;132:2580–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Bosman RJ, Treskes M, et al. Plasma glutamine depletion and patient outcome in acute ICU admissions. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths RD, Jones C, Palmer TE. Six-month outcome of critically ill patients given glutamine-supplemented parenteral nutrition. Nutrition 1997;13:295–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goeters C, Wenn A, Mertes N, et al. Parenteral l-alanyl-l-glutamine improves 6-month outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002;30:2032–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuentes-Orozco C, Anaya-Prado R, Gonzalez-Ojeda A, et al. l-Alanyl-l-glutamine-supplemented parenteral nutrition improves infectious morbidity in secondary peritonitis. Clin Nutr 2004;23:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou YP, Jiang ZM, Sun YH, et al. The effects of supplemental glutamine dipeptide on gut integrity and clinical outcome after major escharectomy in severe burns: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr Suppl 2004;1:55–60 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dechelotte P, Hasselmann M, Cynober L, et al. l-Alanyl-l-glutamine dipeptide-supplemented total parenteral nutrition reduces infectious complications and glucose intolerance in critically ill patients: the French controlled, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:598–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conejero R, Bonet A, Grau T, et al. Effect of a glutamine-enriched enteral diet on intestinal permeability and infectious morbidity at 28 days in critically ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a randomized, single-blind, prospective, multicenter study. Nutrition 2002;18:716–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garrel D, Patenaude J, Nedelec B, et al. Decreased mortality and infectious morbidity in adult burn patients given enteral glutamine supplements: a prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2444–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou YP, Jiang ZM, Sun YH, et al. The effect of supplemental enteral glutamine on plasma levels, gut function, and outcome in severe burns: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2003;27:241–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng X, Yan H, You Z, et al. Effects of enteral supplementation with glutamine granules on intestinal mucosal barrier function in severe burned patients. Burns 2004;30:135–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grau T, Bonet A, Minambres E, et al. The effect of l-alanyl-l-glutamine dipeptide supplemented total parenteral nutrition on infectious morbidity and insulin sensitivity in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1263–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2009;33:277–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr 2009;28:387–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in the mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patient. 2009http://www.criticalcarenutrition.com/docs/cpg/9.4pnglu_FINAL.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Andrews PJ, Avenell A, Noble DW, et al. Randomised trial of glutamine, selenium, or both, to supplement parenteral nutrition for critically ill patients. BMJ 2011;342:d1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cekmen N, AydIn A, Erdemli Ö. The impact of l-alanyl-l-glutamine dipeptide supplemented total parenteral nutrition on clinical outcome in critically patients. e-SPEN, the European e-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism 2011;6:e64–7 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammarqvist F, Wernerman J, Ali R, et al. Addition of glutamine to total parenteral nutrition after elective abdominal surgery spares free glutamine in muscle, counteracts the fall in muscle protein synthesis, and improves nitrogen balance. Ann Surg 1989;209:455–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blomqvist BI, Hammarqvist F, von der Decken A, et al. Glutamine and alpha-ketoglutarate prevent the decrease in muscle free glutamine concentration and influence protein synthesis after total hip replacement. Metabolism 1995;44:1215–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gore DC, Wolfe RR. Glutamine supplementation fails to affect muscle protein kinetics in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2002;26:342–9; discussion 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tjäder I, Rooyackers O, Forsberg AM, et al. Effects on skeletal muscle of intravenous glutamine supplementation to ICU patients. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:266–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones C, Palmer TE, Griffiths RD. Randomized clinical outcome study of critically ill patients given glutamine-supplemented enteral nutrition. Nutrition 1999;15:108–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brantley S, Pierce J. Effects of enteral glutamine on trauma patients. Nutr Clin Pract 2000;15:S13 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hall JC, Dobb G, Hall J, et al. A prospective randomized trial of enteral glutamine in critical illness. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1710–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schulman AS, Willcutts KF, Claridge JA, et al. Does the addition of glutamine to enteral feeds affect patient mortality? Crit Care Med 2005;33:2501–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McQuiggan M, Kozar R, Sailors RM, et al. Enteral glutamine during active shock resuscitation is safe and enhances tolerance of enteral feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2008;32:28–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jolliet P, Pichard C, Biolo G, et al. Enteral nutrition in intensive care patients: a practical approach. Clin Nutr 1999;18:47–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Fabian TC, et al. Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Ann Surg 1992;215:503–11; discussion 11–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore FA, Moore EE, Jones TN, et al. TEN versus TPN following major abdominal trauma–reduced septic morbidity. J Trauma 1989;29:916–22; discussion 22–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soguel L, Chiolero RL, Ruffieux C, et al. Monitoring the clinical introduction of a glutamine and antioxidant solution in critically ill trauma and burn patients. Nutrition 2008;24:1123–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Melis GC, Boelens PG, van der Sijp JR, et al. The feeding route (enteral or parenteral) affects the plasma response of the dipetide Ala-Gln and the amino acids glutamine, citrulvline and arginine, with the administration of Ala–Gln in preoperative patients. Br J Nutr 2005;94:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wischmeyer PE, Lynch J, Liedel J, et al. Glutamine administration reduces Gram-negative bacteremia in severely burned patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial versus isonitrogenous control. Crit Care Med 2001;29:2075–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo M, Bazargan N, Griffith DP, et al. Metabolic effects of enteral versus parenteral alanyl-glutamine dipeptide administration in critically ill patients receiving enteral feeding: a pilot study. Clin Nutr 2008;27:297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bakalar B, Duska F, Pachl J, et al. Parenterally administered dipeptide alanyl-glutamine prevents worsening of insulin sensitivity in multiple-trauma patients. Crit Care Med 2006;34:381–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eroglu A. The effect of intravenous alanyl-glutamine supplementation on plasma glutathione levels in intensive care unit trauma patients receiving enteral nutrition: the results of a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg 2009;109:502–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beale RJ, Sherry T, Lei K, et al. Early enteral supplementation with key pharmaconutrients improves sequential organ failure assessment score in critically ill patients with sepsis: outcome of a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Crit Care Med 2008;36:131–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Macfie J. European round table: the use of immunonutrients in the critically ill. Clin Nutr 2004;23:1426–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wernerman J. Glutamine and acute illness. Curr Opin Crit Care 2003;9:279–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, et al. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med 1995;23:1638–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:657–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The REDOX Study (REducing Deaths due to OXidative Stress) Pharmacy Manual, 2009. http://www.criticalcarenutrition.com/docs/Manual/REDOXSPharmacyManualJuly2009.pdf

- 66.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Day AG, et al. REducing Deaths due to OXidative Stress (The REDOXS Study): rationale and study design for a randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidant supplementation in critically-ill patients. Proc Nutr Soc 2006;65:250–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clifford ME, Banks MD, Ross LJ, et al. A detailed feeding algorithm improves delivery of nutrition support in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Resusc 2010;12:149–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:309–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr 2004;23:1226–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Robert S, Zarowitz BJ, Hyzy R, et al. Bioelectrical impedance assessment of nutritional status in critically ill patients. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:840–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Faisy C, Rabbat A, Kouchakji B, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in estimating nutritional status and outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med 2000;26:518–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.