Abstract

Objective

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) is most widely used as a mortality prediction score in US intensive care units (ICUs), but its calculation is onerous. The authors aimed to develop and validate automatic mapping of physicians' admission diagnoses to structured concepts for automated APACHE IV calculation.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in medical ICUs of a tertiary healthcare and academic centre. Boolean-logic text searches were used to map admission diagnoses, and these were compared with conventional APACHE database entry by bedside nurses and a gold-standard physician chart review. The primary outcome was APACHE IV predicted hospital mortality. The tool was developed in a larger cohort of ICU patients.

Results

In a derivation cohort of 192 consecutive critically ill patients, the diagnosis coefficient coded by three different methods had a positive correlation, highest between manual and gold standard (r2=0.95; mean square error (MSE)=0.040) and least between manual and automatic tool (r2=0.88; MSE=0.066). The automatic tool had an area under the curve (95% CI) value of 0.82 (0.74 to 0.90) which was similar to the physician gold standard, 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) and standard manual entry, 0.81 (0.73 to 0.89). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test demonstrated good calibration of automatically calculated APACHE IV score (χ2=6.46; p=0.6). The automatic tool demonstrated excellent discrimination with an area under the curve value of 0.87 (95% CI 0.83 to 0.92) and good calibration (p=0.58) in the validation cohort of 593 patients.

Conclusion

A Boolean-logic text search is an efficient alternative to manual database entry for mapping of ICU admission diagnosis to structured APACHE IV concepts.

Article summary

Article focus

To develop a fully automated APACHE IV calculator.

To evaluate the efficiency of automatic tool.

To validate the automated APACHE IV calculator on a large cohort of ICU patients.

Key messages

Fully automated calculation of the APACHE IV prognostic score with good discrimination and calibration is possible.

A Boolean logic text search is feasible to map the medical ICU admission diagnosis to the corresponding APACHE IV disease group.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe a fully automatic calculation of the APACHE IV score.

The automated tool presented in this study has a number of limitations. The tool was developed and validated using medical ICU populations in a single institution. Another limitation of the presented tool is related to the difficulty in coding the reason for ICU admission from unstructured clinical notes.

Introduction

Intensive care medicine consumes a large proportion of hospital budgets (10–30%) and national healthcare expenditures.1 Owing to increased demands for quality assessment, qualification of patient treatment and cost–benefit analysis, the need for an accurate outcome prediction score has increased.2 One of the earliest modern risk-adjustment systems, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) score, was introduced in 1981.3 Modified versions (APACHE II, APACHE III and APACHE IV) and various other scores have been developed over the past 20 years.4–6

A major limitation in the use of any prediction score is the amount of time required for its calculation. For example, to calculate the APACHE II score,4 medical personnel have to collect 12 physiological parameters, age, patient's chronic diseases and ICU admission diagnosis. The number of collected variables increased to 26 in APACHE IV along with the number of admission disease categories (116 different groups).

APACHE IV shows a better discrimination ability in predicting hospital mortality than other mortality-prediction models such as MPM0 III and SAPS III. However, the data collection for the APACHE IV calculation takes twice as long as SAPS, and three times as long as the MPM0 III7 calculations. The average time required to calculate APACHE IV manually is 37.3 min (95% CI 28.0 to 46.6 min) per patient. Even the online interfaces offered to calculate the APACHE IV score require a manual entry of up to 52 data points.8 The development of fully automated calculators, which exploit the strengths of high-fidelity Electronic Medical Records (EMRs), could support the use of better prediction models without the additional data-collection burden usually associated with their adoption.

Shabot et al already demonstrated the usefulness of automatic extraction of data from a computerised intensive care unit (ICU) flow sheet for the calculation of an intensity-intervention score.9 Today, programs for automatic calculation of manually entered values are more widely available. Some patient-data-management systems now offer ‘automatic score calculation.’10 Nevertheless, in all these systems, some or all of the data values must be entered manually through a separate interface. In addition to saving time, completely computerised score calculation can reduce interobserver and intraobserver variability and transcription error.11–13 The ideal system would search EMRs automatically for all the components of score calculation including demographics, hospital monitoring, medication administration, laboratory values, and physician and nursing narrative clinical notes.14

For an automated APACHE IV calculation to succeed, the major challenge to be overcome is that associated with ‘mapping’ (matching) chronic conditions and ICU admission diagnoses to structured APACHE disease groups. With this challenge in mind, the specific aims of this study were:

to develop a fully automated APACHE IV calculator, which reliably maps free text physician's notes to structured APACHE IV diagnostic disease groups, using Boolean logic text search of the EMRs of medical ICU patients;

to evaluate the efficiency of this tool by comparing its performance with conventional APACHE manual data entry by bedside nurses and a gold-standard posthoc physician review;

to validate the tool's performance in a larger cohort.

Methods

The study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, an academic medical centre with 1900 beds and 135 000 hospital admissions per year. The combined capacity of the ICUs is 204 beds and 14 800 admissions per year. Saint Mary's Hospital has 183 ICU beds: 24 general medical, 16 medical cardiology, 25 cardiac surgery, eight transplant surgery, 20 thoracic or vascular surgery, 24 trauma critical care, 20 neurological, 26 neonatal (with the option of dual-occupancy stay for twins in four of them) and 16 paediatric. Rochester Methodist Hospital has a 21-bed medical-surgical ICU. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and waived the need for informed consent for this minimal-risk observational study (approval number 07-005642).

Subject selection

In this study, we included a retrospective cohort of patients admitted to Medical ICU. For the derivation cohort, we evaluated consecutive patients' EMRs over 50 days (October–November 2006). Randomly selected patients from the entire year 2006 (excluding derivation cohort) were included in the validation cohort. Patients who had an ICU stay of less than 24 h were excluded.

Data source and data collection

The structural query language (SQL)-based integrative Multidisciplinary Epidemiology and Translational Research in Intensive Care (METRIC) database (METRIC Data mart) accumulates data within 1 h from its entry into the EMRs.15 METRIC Data mart was the primary data source, providing the linked demographic, monitoring, laboratory, intervention and outcome data required for the automated APACHE IV score calculator.

Age was recorded as a continuous variable and calculated from the date of birth to the date of admission to ICU. For acute physiological variables, the most abnormal value available in the first 24 h of ICU was used. Chronic health variables were extracted from the APACHE database and were collected manually by nurses. To capture the required ICU admission diagnosis (the reason for ICU admission), a free-text search was applied to the physician's ICU admission note. In a pilot study, we compared natural-language processing and a Boolean-logic text search to map the ICU admission diagnosis.16 The performance of the Boolean logic free-test search was equivalent. Also, the use of natural-language processing required additional hardware and software resources that increased the complexity. Because of this, we chose to use the Boolean-logic free-test search in this project.

The first diagnosis mentioned under the subheading of ‘Impression’ (Problems/diagnoses) was captured, and this was mapped to the structured APACHE IV diagnostic groups. The rules which matched the impression diagnosis with the APACHE IV diagnostic group were developed by the authors, who linked them directly to the disease group. When the ICU admission diagnosis was unavailable or not coded by the automatic tool, the corresponding predictive coefficient was replaced by the ‘generic’ adjusted diagnosis coefficient of −0.42772. Adjusted diagnosis coefficients were calculated using mean structured diagnosis coefficients, adjusted for diagnosis prevalence.

Free-text search

A free-text search is a technique where the designed search engine screens all the words in a document or database to match the provided search words. When screening large databases, the major limitation of a free-text search is precision. Several techniques have been described to improve the precision. In the current project, we have used field-restricted search and Boolean logic to perform a more specific search. A field-restricted search enables the search to be limited to a particular section of the document. We have limited the search to the first diagnosis mentioned under the ‘Impression’ section of the clinical notes. The Boolean logic or operators (eg, AND, OR, NOT) further refine the search based on the logic used. The use of AND operator limits the search until both the given search terms are matched where the OR operator includes either of the terms matched.

APACHE score

APACHE is the most widely used mortality prediction model in adult ICUs in the USA. In the APACHE score, the physiological variables are derived from the worst values in the first 24 h period of the patients' ICU stay.4 5 The score is also derived from textual concepts including chronic health status, physiological measures and acute diagnoses.17

Standard manual mapping of admitting diagnosis for APACHE score calculation

As a standard practice in the host institution, diagnosis mapping is performed by trained bedside nurses, and data entered into the APACHE database in the 24 h time frame after admission to the ICU. Diagnosis mapping is based on the nurses' interpretation of the free-text admission diagnosis. As a nurse standard practice we used APACHE III coded diagnoses recorded in hospital EMR. For the purposes of this study, APACHE III structured diagnoses (78) were mapped to APACHE IV structured diagnoses (116) by a coinvestigator clinician intesivist (OG).

Development of the gold standard for mapping of admission diagnosis for APACHE score calculation

ICU admission diagnosis was mapped using the ICU admission note of the attending physician. Attending physicians at our institution are present on site 24/7 and dictate their notes which are transcribed with priority and 24 h a day. Admission notes are usually available within 2–6 h after their dictation and within 24 h of patients' ICU admissions. Admission diagnoses were defined as originally described by Zimmerman et al6:‘injuries, surgical procedures, or events that were most immediately threatening to the patient and required the services of the ICU.’ Two physician researchers reviewed cases and assigned APACHE diagnostic codes (κ=0.58). First reviewer utilised all clinical information available in EMR and second only pertinent admission note. Mismatched cases were analysed by a physician coinvestigators (CAT-A). Agreement between two of the three reviewers was considered the gold standard. Where there was no agreement between the three reviewers, a super reviewer (physician researcher) was utilised to adjudicate. In five cases, the gold standard could not be determined, as the super reviewer refused to accept the diagnosis of any of the three earlier reviewers, and so the records were excluded from the study.

Automatic calculation of APACHE IV predicted mortality

The automatic tool was an SAS program that retrieves all information necessary for APACHE IV calculation data from METRIC Data mart using SQL queries. For text processing, a Boolean-logic text search of predefined terms was used. APACHE IV outcome data were saved back to METRIC Data mart. The SAS program ran automatically using a schedule and required minimal ongoing support. For APACHE IV calculation, the automated APACHE IV calculation system was based on the equations available at Cerner Corporation web page (http://www.cerner.com/public/filedownload.asp?LibraryID=40394).

Statistical analysis

Correlation statistics and Bland–Altman plots were used to compute the agreement in coding diagnosis coefficient using different mapping methods, manual, gold standard and automatic. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) and determine the accuracy of the APACHE IV prediction of hospital mortality. An AUC of >0.70 is considered evidence of a good predictive value.18 Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-fit statistics were used to test the calibration of the automated calculator. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP and SAS statistical software packages.

Results

After excluding patients who did not have research authorisation (n=14), those for whom the ICU length was less than 24 h (N=138) and patients whose gold standard diagnosis could not be determined (n=5), a total of 192 patients were enrolled in the derivation cohort. Complete data on physiological parameters, chronic health conditions and admission diagnosis required for APACHE IV calculation and hospital mortality were available for all patients in the cohort. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the derivation cohort are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the derivation and validation cohorts

| Variables | Derivation cohort (n=192) | Validation cohort (n=593) | p Value |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 61±19.6 | 60.8±20.9 | 0.92 |

| Gender, male (%) | 100 (52) | 308 (51.8) | 0.97 |

| APACHE III score, median (IQR) | 56 (40–75) | 51 (32–71) | <0.05 |

| Most common APACHE IV diagnosis groups; n (%) |

|

|

|

| ICU mortality (%) | 9.4 | 4.7 | 0.01 |

| Hospital mortality (%) | 16.1 | 12.3 | 0.17 |

| ICU length if stay, median (IQR) | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | <0.01 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR) | 5.6 (2.6–10.1) | 3.7 (1.8–6.8) | <0.01 |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BACPNEU, pneumonia, bacterial or other; GIBLEED, bleeding, GI, upper or unknown location; ICU, intensive care unit; OD, overdose, drug withdrawal; RESPOTH, sleep apnoea, atelectasis, pulmonary haemorrhage/haemoptysis, haemothorax, primary/idiopathic hypertension—pulmonary, near-drowning accident, pneumothorax, respiratory—medical, other, restrictive lung disease (ie, sarcoidosis, pulmonary fibrosis), smoke inhalation, weaning from mechanical ventilation (transfer from another unit or hospital only).

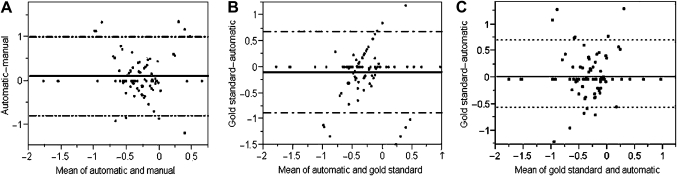

The diagnosis coefficient coded by three different methods had a positive correlation, the highest correlation being between the manual and the gold standard (r2, mean square error (MSE)=0.95, 0.040), the lowest between the manual and the automatic calculation tool (r2, MSE=0.88, 0.066) and an intermediate correlation between the automatic tool and the gold standard (r2, MSE=0.91 (0.058)). The bias in value of diagnosis coefficient was least when manual calculation was compared with the gold standard, 0.013 (95% CI −0.547 to 0.574) and maximal when comparing the manual with the automatic calculation tool; 0.115 (95% CI −0.778 to 1.008). On drawing Bland–Altman plot for diagnosis coefficient coded by three methods, bias between gold standard and automatic calculation tool, calculation was intermediate: −0.102 (95% CI −0.881 to 0.677) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bland–Altman plot of the predictive mortality coefficient showing the correlation between manual and automatic calculation (A), gold standard and automatic calculation (B), and gold standard and manual calculation (C) in the derivation cohort.

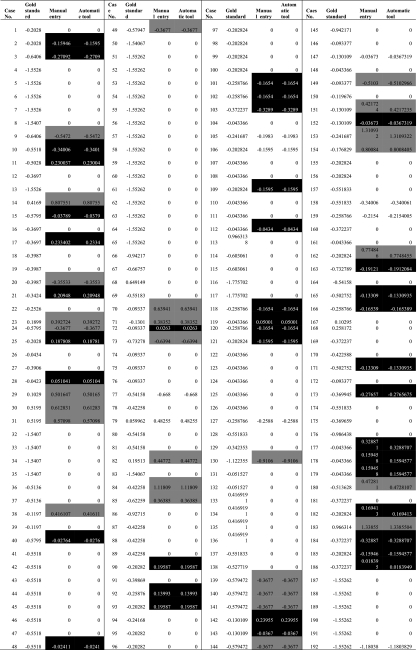

Table 2 shows the mismatch in coding admission diagnosis by manual, gold standard and automatic tools. A Boolean-logic text search did not code ICU admission diagnoses for 37 (19.3%) subjects. Among diagnoses that were not coded by a Boolean-logic text search, hypotension was most prevalent (in 10 subjects) followed by altered mental status (in four subjects) and alcohol intoxication (in two subjects). ‘Hypotension,’ ‘altered mental status’ and ‘alcohol intoxication’ are not directly available in the list of APACHE IV diagnoses.

Table 2.

Disagreement among automatic tool, manual entry and the gold standard, and the corresponding differences in predictive coefficients

|

For the remaining patients (n=155), where a first ICU diagnosis was available in the APACHE diagnoses list, the automatic tool mapped APACHE IV diagnoses correctly in 143 (93.8%) patients and miscoded in 12 patients (6.2%). Among diagnoses which were miscoded, respiratory distress was the most common (six subjects with respiratory distress were coded as ‘RESPCA’ which is allotted for ‘Cancer, laryngeal/oral/tracheal/lung’). A common minor mismatch was the coding of lower GI bleeding as GIBLEED (unspecified GI bleed, three subjects) and SGIBLEE (surgery for GI bleed, one subject).

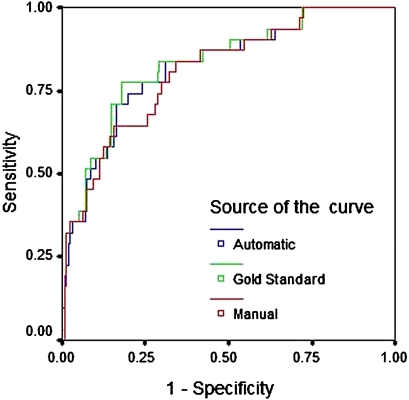

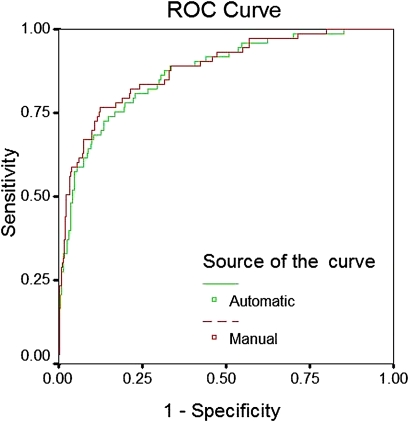

On plotting the receiver operating characteristic curve of predicted hospital mortality, the automatic calculation tool using a Boolean logic text search showed an AUC (95% CI) value of 0.82 (0.74 to 0.90), which was similar to the physician gold standard, 0.83 (0.75 to 0.91) and standard manual entry, 0.81 (0.73 to 0. 89) (figure 2). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test demonstrated sufficient calibration of automatically calculated APACHE IV scores (χ2=6.4651; 8 degrees of freedom; p=0.5953).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curve showing the predictive performance of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV calculation when the diagnosis was mapped by an automatic tool, manual entry and a gold standard (derivation cohort).

Validation cohort

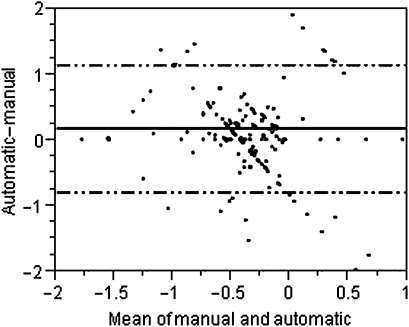

Based on the analysis of the derivation cohort, additional concepts for automatic calculation were added; likewise, ‘alcohol intoxication’ was coded as ‘OD,’ ‘code 45/cardiac arrest’ as ‘CARDARR’ and ‘hypokalemia’ as ‘ACIDBASE.’ Modified rules were tested on 593 random subjects. The automatic tool did not code ICU admission diagnoses for 192 (32.2%) patients. On plotting the Bland–Altman plot using the difference and mean value of the diagnosis coefficient coded manually and by the automatic tool, the bias between methods in coding diagnosis coefficient was found to be 0.168 (95% CI −0.799 to 1.135) (figure 3). The discriminatory power of APACHE IV score calculated using the automatic tool remained excellent (AUC=0.87 (0.83 to 0.92)) and was similar to manual coding of the admission diagnosis: AUC (95% CI)=0.88 (0.84 to 0.93) (figure 4). The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test showed a good calibration for the APACHE IV score calculated by the automatic tool (χ2 6.6381; 8 degrees of freedom; p=0.5761).

Figure 3.

Bland–Altman plot of predictive mortality coefficient on manual and automatic calculation in the validation cohort. The correlation between manual and automatic model coding of the predictive mortality coefficient was less than it was in the derivation cohort (r2, mean square error=0.42, 0.423).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing the predictive performance of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV calculation when the diagnosis was mapped using an automatic tool or manual entry (validation cohort).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we developed and internally validated a model for automatic calculation of APACHE IV using Boolean logic text search for mapping medical ICU admission diagnosis. The automatic model showed a modest agreement in coding medical ICU admission diagnosis with routinely performed manual coding by trained bedside nurses, and the study initiated a physician gold standard. Despite this limitation, the APACHE IV calculated using the developed automatic model demonstrated excellent discrimination in predicting hospital mortality. The discriminatory ability of the automatic tool was improved by reviewing the mismatches, and this was confirmed in the larger validation cohort. Having an excellent prognostic value in spite of moderate interobserver agreement with the Gold Standard is likely due to the modest specific contribution of ‘diagnosis’ to the overall APACHE IV calculation which also takes into account multiple physiological and laboratory values. Therefore, the small differences seen between the coefficients of clinically related diagnoses were unlikely to influence the overall accuracy of the fully automatic APACHE IV calculation. This study also demonstrates the poor interobserver agreement in medical ICU admission diagnosis mapping for the purpose of APACHE IV calculation.

The major factors influencing the use of any mortality prediction model in ICU include the electronic availability of risk scores, resources and technology.19 The increasing availability of EMR in conjunction with the significant burden associated with manual collection and calculation of mortality prediction parameters will likely drive the development of automated alternatives such as that presented in this paper.

In the past, little effort was made in developing automatic calculations based on mortality-prediction scores such as APACHE IV. Some of the key barriers to their development included the unavailability of data within EMRs and difficulties associated with mapping admission diagnoses and chronic health status to structured APACHE IV concepts. Automated calculation of the APACHE II score from EMRs in the ICU has been attempted previously. Junger and colleagues at University Hospital Giessen, Germany,20 used SQL scripts on a dataset of 524 patients. In their retrospective study, physiological parameters and age were extracted directly from the EMR database, and International Classification of Diseases, Version 9 (ICD-9) was used to map chronic diseases. The AUC for the automatically calculated modified APACHE II score was 0.790 (95% CI 0.712 to 0.825) and a goodness-of-fit test showed good calibration.20 They found all the acute physiological parameters easy to collect, but chronic health conditions, which are entered manually as free text by the medical personnel, were difficult to map. The major limitation of their study was the unavailability of the comparison group, no-manual-entry comparison group and the absence of the gold standard. Mapping from APACHE IV classification to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms has also been carried out in previous studies. Eighty-four per cent of diagnostic categories in APACHE IV could be mapped to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms concepts.21

Similar efforts were made to calculate the SAPS II score automatically in a retrospective cohort of 524 patients from an academic surgical ICU at University Hospital Giessen, Germany.2 The study cohort had many missing laboratory values and clinical parameters required for SAPS II score calculation. Despite these limitations, their automatic tool demonstrated a good discriminatory power and calibration.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe a fully automatic calculation of the APACHE IV score. Several limitations need to be acknowledged for appropriate interpretation of our results. The automated tool presented in this study was developed and validated using medical ICU populations in a single institution. The tool has not been developed for the surgical ICU population, and an algorithm for surgical diagnoses needs to be included and tested prior to deployment in this environment. To ensure external validity, the methodology should be replicated in other institutions equipped with EMRs and using the expertise of local clinical experts. The major limitation of the presented tool is related to the difficulty in coding the reason for ICU admission from unstructured clinical notes. In this study, we used the first diagnosis mentioned under the heading ‘impression’ in the ICU admission note, assuming this to be the primary reason for medical ICU admission. On other hand, the Boolean-logic text search was not run on all the diagnoses in the admission note. A larger number of diagnoses would reduce the discrepancy, as the computer algorithm developed did not have the ability to determine the primary reason for ICU admission from a list of diagnoses. The automatic tool coded the first diagnosis accurately in three-quarters of patients. In missed subjects, the diagnosis mentioned in the ICU admission note was not present in the APACHE diagnosis groups (unspecified ‘hypotension’). Despite coding the admission diagnosis with good accuracy, the bias between gold-standard and automatic calculations suggests that the first listed diagnosis in the ICU admission note is not always the primary reason for ICU admission in our setting. An effort to distinctly document the primary ICU admission diagnosis could potentially improve the efficacy of such computer-based automatic calculations.

Alternative solutions such as mapping of the APACHE IV diagnosis to ICD-9 codes are problematic, as the ICD-9 coding in the ICU is often delayed until after hospital discharge. Moreover, in many health systems (including US), ICD-9 codes are used for billing, which limits its clinical accuracy.22

On reviewing mismatching in coding admission diagnosis, it was observed that relatively similar diagnoses were allotted different diagnosis groups for APACHE calculation. For example, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and lower GI bleeding are coded as GIBLEED and GIBLEUL, respectively. The structured diagnosis coefficients for these conditions are very similar to each other, −0.55183 and −0.57947, respectively. As a result, many of the miscoded diagnoses did not affect predicted mortality to any great extent. In 16 subjects, mismatched codes contributed to a significant difference in structured diagnosis coefficient (ie, >0.35). This was largely attributed to the fact that many of these patients had than one admission diagnosis and that the first diagnosis in the list of diagnosis in ICU admission note was not always the primary reason for ICU admission.

Conclusion

This study outlines the development and validation of a fully automated calculation of the APACHE IV score, which utilised a Boolean-logic text search to map the medical ICU admission diagnosis to the corresponding APACHE IV disease group. The tool developed here demonstrated consistent and good discrimination and calibration compared with the established and gold-standard references, when used for medical ICU mortality prediction.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Chandra S, Kashyap R, Trillo-Alvarez CA, et al. Mapping physicians' admission diagnoses to structured concepts towards fully automatic calculation of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation score. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000216. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000216

Funding: This publication was made possible by Grant Number 1 KL2 RR024151 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research and the Mayo Foundation. This study was supported in part by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute K23 HL78743-01A1.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Contributors: SC contributed to data management and drafting of the manuscript. RK contributed to data collection, case reviews and management, and revision of the manuscript. CAT-A contributed to case reviews and revision of the manuscript. MY contributed to data collection, case reviews and revision of the manuscript. MT contributed to case reviews and revision of the manuscript. ACH contributed to automatic tool development, data analysis and revision of the manuscript. BWP contributed to the design of the study and revision of the article. OG contributed to the design of the study and revision of the article. VH contributed to the design of the study and revision of the article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Polderman KH, Metnitz PG. Using risk adjustment systems in the ICU: avoid scoring an ‘own goal’. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:1471–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel JM, Junger A, Bottger S, et al. Outcome prediction in a surgical ICU using automatically calculated SAPS II scores. Anaesth Intensive Care 2003;31:548–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knaus WA, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE—acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Crit Care Med 1981;9:591–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest 1991;100:1619–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, et al. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2006;34:1297–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuzniewicz MW, Vasilevskis EE, Lane R, et al. Variation in ICU risk-adjusted mortality: impact of methods of assessment and potential confounders. Chest 2008;133:1319–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.APACHE ® IV Calculator: Middle East Critical Care Assembly, 2010. http://www.mecriticalcare.net/icu_scores/apacheIV.php [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shabot MM, Leyerle BJ, LoBue M. Automatic extraction of intensity-intervention scores from a computerized surgical intensive care unit flowsheet. Am J Surg 1987;154:72–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metnitz PG, Lenz K. Patient data management systems in intensive care—the situation in Europe. Intensive Care Med 1995;21:703–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen LM, Martin CM, Morrison TL, et al. Interobserver variability in data collection of the APACHE II score in teaching and community hospitals. Crit Care Med 1999;27:1999–2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polderman KH, Christiaans HM, Wester JP, et al. Intra-observer variability in APACHE II scoring. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1550–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polderman KH, Jorna EM, Girbes AR. Inter-observer variability in APACHE II scoring: effect of strict guidelines and training. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1365–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herasevich V, Keegan MT, Tines D, et al. ICU Data Mart: Informatics Infrastructure for Automatics Calculation of Critical Care Prognostic Scores. 2008 Summit of Translation Bioinformatics Proceeding, AMIA, 2008:156 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herasevich V, Pickering BW, Dong Y, et al. Informatics infrastructure for syndrome surveillance, decision support, reporting, and modeling of critical illness. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:247–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trillo Alvarez CA, Trusko B, Hanson AC, et al. Automatic Calculation of APACHE Admission Diagnoses: Natural language Processing (NLP) vs. ‘Natural Brain Processing’. AMIA 2009, San Fransisco, AMIA, 2009:1054 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemeshow S, Le Gall JR. Modeling the severity of illness of ICU patients. A systems update. JAMA 1994;272:1049–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner DP, Knaus WA, Draper EA. Statistical validation of a severity of illness measure. Am J Public Health 1983;73:878–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon EG, Jha AK, Christino M, et al. Assessing the level of healthcare information technology adoption in the United States: a snapshot. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2006;6:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junger A, Bottger S, Engel J, et al. Automatic calculation of a modified APACHE II score using a patient data management system (PDMS). Int J Med Inform 2002;65:145–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakhshi-Raiez F, Cornet R, de Keizer NF. Cross-mapping APACHE IV ‘reasons for intensive care admission’ classification to SNOMED CT. Stud Health Technol Inform 2008;136:779–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shenefelt PD. Limits of ICD-9-CM code usefulness in epidemiological studies of contact and other types of dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat 1998;9:176–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.