Abstract

Background

Eating disorders are of major significance both in clinical medicine and in society at large. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa almost exclusively afflict young persons, severely impairing their physical and mental health. The peak ages for these diseases are in late adolescence and young adulthood; patients therefore suffer setbacks both in school and/or in their occupational careers. This scientifically based S3 guideline was developed with the intention of improving the treatment of eating disorders and motivating future research in this area.

Methods

The existing national and international guidelines on the three types of eating disorders were synoptically compared, the literature on the subject was systematically searched, and meta-analyses on bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder were carried out. 15 consensus conferences were held, as a result of which 44 evidence-based recommendations were issued.

Results

Anorexia and bulimia nervosa are diagnosed according to the ICD-10 criteria (International Classification of Diseases), binge-eating disorder according to those of the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). Psychotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for all three disorders, and cognitive behavioral therapy is the form of psychotherapy best supported by the available evidence. The administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) can be recommended as a flanking measure in the treatment of bulimia nervosa only. The evidence does not support any type of pharmacotherapy for anorexia nervosa or binge-eating disorder. Bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder can usually be treated on an outpatient basis, as long as they are no more than moderately severe; full-fledged anorexia nervosa is generally an indication for in-hospital treatment.

Conclusion

This guideline contains evidence- and consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders. If strictly implemented, it should result in improved care for the affected patients.

The main symptom of anorexia nervosa (AN) is self-induced malnutrition with weight loss that may amount to cachexia. According to the diagnostic criteria, the body weight is so low that health impairment is to be feared. In adults, this danger is seen when the body mass index (BMI) drops below 17.5kg/m2; in children and adolescents, it corresponds to being below the 10th BMI-for-age percentile. Since children have a much smaller fat mass than adults or adolescents, the somatic sequelae of starving during AN occurring early in life are more serious and have negative consequences for, e.g., bone density, growth in height, and cerebral maturation. AN is often accompanied by other psychological illnesses such as depression, anxiety, or compulsive disorder. The average frequency of AN in young women aged between 14 and 20 years varies between 0.2% and 0.8% (1) (eBox 1).

eBox 1. ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa (F 50.0) (2).

Actual body weight at least 15% below expected weight, or body mass index 17.5 or less (in adults).

-

Weight loss is caused by the avoidance of high-calorie foods and at least one of the following:

Self-induced vomiting

Self-induced purging

Excessive exercise

Use of appetite suppressants and/or diuretics

Distorted body image as a specific psychological disorder

Endocrine disorder, manifest in the female as amenorrhea and in the male as a loss of libido

If onset is prepubertal, the puberty in boys and girls may be delayed (growth ceases; in girls the breasts do not develop)

The 10-year mortality in this group is around 5%. This is considerably more than 10 times the mortality from other causes in this age group in the general population (1, 2). Follow-up studies have shown that around 40% of patients with AN show good treatment success, while 25% have moderate and 30% poor treatment success (3).

The term “bulimia nervosa” (BN) refers to the uncontrollable urge for frequent high-calorie food. Episodes of excessive uncontrolled eating alternate with rigorous fasting, vomiting, and abuse of laxatives and/or diuretics. At 2%, BN has a notably higher prevalence than AN. Both of these eating disorders affect women in the large majority of cases; men are affected in only 5% to 10% of cases (1) (eBox 2).

eBox 2. ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa (F 50.2) (2).

The constant obsession with eating and the overwhelming desire for food leads to episodes of eating large amounts of food in short time periods.

There are efforts made to reduce the effect of eating foods perceived as fattening in the form of self-induced vomiting and other purging techniques, alternating episodes of calorie restriction, using appetite suppressants, thyroid preparations or diuretics. People with diabetes may refrain from using their insulin treatment.

There is an intense fear of becoming fat, which leads to the desire to reach a specific body weight much lower than is considered normal or healthy for height and age.

In many cases, the bulimia follows an episode of anorexia nervosa, although the period of time between the two disorders may vary considerably.

According to studies in the USA, about 50% of patients with BN are free of symptoms after more than 5 years, while about 20% continue to fulfill all the criteria of the disorder (4).

The diagnosis “binge eating disorder” (BED) was incorporated by the American Psychiatric Association in the fourth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) in 1994 (5); in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) it can only be coded under the category “eating disorder, unspecified” (F50.9). The course of BED has been the object of less research than AN and BN, but its prognosis is better. Remission rates in outpatient psychotherapy range between 50% and 80% (5– 7) (eBox 3).

eBox 3. Diagnostic criteria for binge eating disorder (7).

-

Recurring episodes of binge eating. The two characteristics of a binge eating episode are:

Eating a much larger amount of food than most people would consider normal under similar circumstances and within the same time frame (eating may continue for several hours).

While eating, there is a feeling of loss of control over the amount of food or type of food being consumed.

-

Binge eating episodes are related to at least three of the following:

Eating until feeling uncomfortably full.

Eating large quantities of food when not even hungry.

Eating noticeably faster than is considered normal.

Eating alone due to embarrassment of overeating.

Feelings of disgust, depression, or guilt after a binge.

There is obvious distress concerning binge eating behavior.

On average, binge eating takes place twice weekly, and has done so for 6 months.

There are no recurring efforts to compensate for binge eating, such as purging or excessive exercise. The disorder occurs at times other than during episodes of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

The prevalence of BED varies in the general population between 0.7% (8) and 4.3% (9); women are affected about 1.5 times as often as men (10).

The eating disorders AN and BN are of great social significance because they almost exclusively affect young people—with serious consequences for their physical and mental health. Overall, eating disorders give rise to enormous direct and indirect costs. Costs of 5300 EUR for AN and 1300 EUR for BN per patient per year are to be expected. Haas et al. (11) calculated an average of 4647 EUR in inpatient costs per patient. Krauth et al. (12) calculated overall costs of 12 800 EUR for a patient with AN. These costs are way above the average costs for inpatients with other diseases. So far as the authors know, no cost analyses have yet been done for BED.

Methods

The initiator of the S3 guideline was the German Society for Psychosomatic Medicine and Medical Psychotherapy (DGPM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Ärztliche Psychotherapie) and the German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM, Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin) in collaboration particularly with the German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Medicine, and Psychotherapy (DGKJP, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Psychotherapie) the German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy, and Neurology (DGPPN, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Neurologie) and the German Psychological Society (DGPs, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie), supported by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenleschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (Box 1). Following the procedure required by the AWMF, 44 statements and recommendations were agreed by consensus at a total of 15 meetings of experts and four moderated meetings. An attempt was made to integrate international guidelines: the British guideline from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (13) and the guideline of the American Psychiatric Association (14) were important sources. In addition, systematic literature searches and meta-analyses (15, 16) were carried out in order to include more recent studies, but also to allow for the fact that the recommendations in the Anglo-American guidelines do not always mesh with the German health care system.

Box 1. Guideline group.

Responsible for the S3 guideline

German Society of Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (DGPM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie), German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM, Deutsches Kollegium für Psychosomatische Medizin)

Coordination and spokesperson

Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Herpertz, Klinik für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, LWL-Universitätsklinikum Bochum, Ruhr-Universität Bochum

Working group members

PD Dr. med. Dipl.-Psych. Ulrich Cuntz (Prien am Chiemsee)

Prof. Dr. med. Dipl.-Psych. Manfred M. Fichter (Prien am Chiemsee)

PD Dr. med. Hans-Christoph Friedrich, Heidelberg

Dr. rer. nat. Dipl.-Psych. Gaby Groß, Tübingen

Dr. med. Ulrich Hagenah, Aachen

Dr. phil. Dipl.-Psych. Armin Hartmann, Freiburg

Prof. Dr. med. Beate Herpertz-Dahlmann, Aachen

Prof. Dr. med. Wolfgang Herzog, Heidelberg

PD Dr. med. Kristian Holtkamp, Bad Neuenahr

PD Dr. rer. nat. Dipl.-Psych. Burkard Jäger, Hannover

Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Dipl.-Psych. Corinna Jacobi, Dresden

Prof. Dr. med. Annette Kersting, Leipzig

Prof. Dr. rer. soc. Dipl.-Psych. Reinhard Pietrowsky, Düsseldorf

Dr. phil. Dipl.-Psych. Stephan Jeff Rustenbach, Hamburg

PD Dr. Dr. rer. medic. Dipl.-Psych. Harriet Salbach-Andrae, Berlin

Prof. Dr. med. Ulrich Schweiger, Lübeck

Prof. Dr. phil. Dipl.-Psych. Brunna Tuschen-Caffier, Freiburg

PD Dr. rer. nat. Dipl.-Psych. Silja Vocks, Bochum

Prof. Dr. phil. Dipl.-Psych. Jörn von Wietersheim, Ulm

Prof. Dr. med. Almut Zeeck, Freiburg

Prof. Dr. med. Stephan Zipfel, Tübingen

Prof. Dr. med. Martina de Zwaan, Erlangen

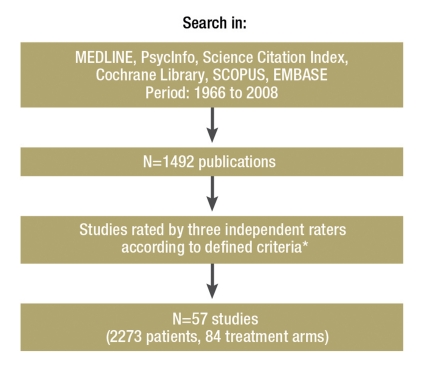

As an example, the Figure shows the literature search for studies on the treatment of AN.

Figure.

Literature search for studies of treatment of anorexia

*Evaluation criteria:

Diagnosis: Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa must be according to a defined diagnostic system (ICD-9/10, DSM-II, DSM-III-R or DSM-IV or Morgan–Russell criteria).

Psychotherapeutic treatment: The study must contain at least one psychotherapeutic treatment arm (psychotherapeutic intervention may include counseling. All settings – outpatient, day patient, inpatient – and combinations thereof are included).

Repeated measurements: Studies must report at least two observation time points (pre- and post-, or pre- and follow-up). One of these measurement points must describe the status before treatment began.

Weight data: Weight data must be reported, such as for example body mass index, % ABW (average body weight), % MMPW (mean matched population weight).

Sample size: The sample size of the entire study must be equal to or greater than the number of study arms × 10 (e.g., 11 + 9 = 20; > = 10 × 2).

No mixed samples: Study arms must not mix patients with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Patients with bulimic anorexia and restrictive anorexia may be mixed, but the weight criterion (<17.5 BMI or <85% MMPW on admission) must be fulfilled.

Observation period: The mean observation time, i.e., the time from T1 to T2, must be less than 3.5 years.

Diagnosis

A preliminary diagnosis of AN in a young woman is easier than one of BN or BED, not least because of the patient is so under weight. Good indicators of BN are female sex, peak manifestation at the age of 18, weight fluctuations, and in particular emotional and mental fixation on body weight, eating, and physical activity. BED, unlike AN and BN, does not usually reach the level of a disorder except in the context of overweight and obesity, especially when the eating disorder is perceived both subjectively and objectively as counterproductive in the desire to lose weight. Diagnosis of an eating disorder requiring treatment should be on the basis of positive screening according to the criteria of ICD-10 (2) or DSM-IV (4) (Box 2).

Box 2. Criteria for suspecting an eating disorder.

Low body weight

Amenorrhea or infertility

Dental damage, especially in young patients

Worries about body weight even though it is normal

Unsuccessful attempts to lose weight in patients who are overweight or obese

Gastrointestinal disorders that cannot be ascribed to another medical cause

Delayed growth in children

Parents worried about their child’s weight and eating behavior

In addition to measuring height and weight, the screening questions in Box 3 are appropriate.

Box 3. Screening questions.

“Are you happy with your eating behavior?”

“Are you worried about your weight or your food?”

“Does your weight affect your feeling of self-worth?”

“Do you worry about your figure?”

“Do you eat in secret?”

“Do you vomit when you feel uncomfortably full?”

“Are you worried because sometimes you can’t stop eating?”

Because of the danger that eating disorders will become chronic, with physical and psychological complications, motivating the patient to undertake treatment is the focus of the first consultations. These should include giving comprehensive factual information about the eating disorder, including its risks, but without frightening the patient. In patients with AN in particular, cognitive impairment due to the cachexia must be taken into account. The information should include the causes and course of the disorder, and also its possible complications and co-morbidities. The formation of the therapeutic relationship is particularly important, whether the patient is an adult or a child or adolescent. Including parents or guardians in the therapeutic process is essential. A solid therapeutic relationship should be built up with both the child/adolescent and the parents, and if appropriate with any other significant persons.

Anorexia nervosa

Studies on the treatment of AN show only a moderate to low level of evidence, among other things because of low case numbers, the lack of valid control conditions, and the use of multimodal therapy approaches in which the individual treatment elements are not described. A meta-analysis shows large effect sizes (>1) (17) in relation to weight gain in both the outpatient (260 g/week) and the inpatient setting (530 g/week) (16). Controlled studies exist for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), psychodynamic therapy (PT), and family therapy, among others. However, these studies do not allow any conclusion about which method of treatment is to be preferred (level of evidence [LOE] Ib). A disorder-specific psychotherapy targeted at AN is, however, to be preferred over a nonspecific procedure (LOE II, grade of recommendation [GoR] B) (Table).

Table. Level of evidence and grade of recommendation.

| Level of evidence = LOE | |

| Ia | Evidence from a meta-analysis of at least three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) |

| Ib | Evidence from at least one RCT or a meta-analysis of fewer than 3 RCTs |

| IIa | Evidence from at least one well-designed controlled trial without randomization |

| IIb | Evidence from at least one well-designed quasi-experimental descriptive study |

| III | Evidence from well-designed nonexperimental observational studies, e.g., case-control studies, correlation studies, and case reports |

| IV | Evidence from reports by expert committees or expert opinion and/or clinical experience of recognized authorities |

| Grade of recommendation = GoR | |

| A | “Should“ recommendation: At least one RCT of overall good quality and consistency, directing related to the recommendation and not extrapolated (levels of evidence Ia and Ib) |

| B | „Ought to“ recommendation: Well-conducted clinical studies, but not RCTs, directly related to the recommendation (levels of evidence II or III), or extrapolation from level of evidence I, if there is no relation to the specific question at issue |

| O | „May“ recommendation: Reports from expert groups or expert opinion and/or clinical experience of recognized authorities (evidence category IV) or extrapolation from levels of evidence IIa, IIb, or III; this grade show that no directly applicable good-quality clinical studies exist or were available |

| CCP | (Clinical consensus point): Recommended as good clinical practice in consensus and on the basis of the clinical experience of the members of the guideline group as standard in treatment, for which no experimental scientific research is possible or aimed at |

Treating AN is a long process that will continue for months even if all goes well, and usually requires a management plan including inpatient, day patient, and outpatient treatment (LOE IV; GoR clinical consensus point [CCP]). However, there are no confirmed empirical data that allow an evidence-based decision for a particular setting (16). As a rule, for a patient with full-blown AN who is markedly under weight, treatment on an inpatient basis is indicated initially (GoR CCP).

The goal of treatment of AN is normalizing body weight and eating behavior and overcoming the psychological problems associated with AN. Clearly structured symptom-orientated treatment components are very important, especially at the start of treatment (GoR CCP), and as are considerations of nutrition management.

To achieve adequate weight gain requires an energy input considerably higher than what is needed for ordinary metabolism; how much higher depends on the patient’s body weight. During the initial therapy phase, patients may show a marked tendency to edema as part of a pseudo-Bartter syndrome, leading to a gain in weight without any substantial change in body mass. Patients with AN generally have an ambivalent attitude to changing their weight and eating behavior. Working to motivate them is therefore a central task of the therapist and should be kept in view throughout the entire treatment process (LOE III, GoR B).

Since the low body weight often leads to a life-threatening condition, in rare cases, among patients with little insight into their disorder, forced treatment may be necessary. Forced treatment is experienced by the patients as extremely stressful and should therefore be avoided as much as possible through intensive motivational support and treatment. Should it still be necessary, it should only be performed in stages (arrangement of guardianship, compulsory admission, forced feeding) (GoR CCP).

Children and at least younger adolescents often are not yet sufficiently mature to be able to realize the gravity of the disease and the need for treatment; in these cases usually the parents or guardians are of prime importance in ensuring that treatment is arranged and carried out. For this reason, they should be given comprehensive information about the disorder and the treatment it requires (GoR CCP).

Psychopharmaceuticals have been shown to be ineffective in AN (LOE Ib). In patients who are constantly preoccupied with eating and weight-related anxiety, and in those with physical hyperactivity that cannot be controlled in any other way, the use of low-dose neuroleptics such as olanzapine may be justified, as an off-label medication on an individual basis (LOE II, GoR B). Drugs with low extrapyramidal side effects should be preferred. Antidepressants do not improve the course of AN (LOE Ia, GoR A). They are occasionally used to treat co-morbid depressive symptoms (Box 4).

Box 4. Recommendations for treatment of anorexia nervosa.

Treatment should be adapted to the disorder and should take into account the physical aspects of the disease (clinical consensus point [CCP]).

Outpatient, day patient, and inpatient treatments should take place in centers or with therapists with expertise in the treatment of eating disorders and should contain disorder-specific elements (CCP).

In the treatment it should be borne in mind that the healing process usually takes many months if not years (CCP).

Forced treatment of anorexia nervosa should only take place when all other measures have been exhausted, including contact with other centers (CCP).

With young patients (children, adolescents) who are still living with their family of origin, the parents, close relatives, or guardians should be involved in the treatment (grade of recommendation B).

In inpatient treatment, the attempt should be made to restore weight to normal or near normal (grade of recommendation B).

In the inpatient setting, a weight gain of between 500 g and a maximum of 1000 g per week should be aimed at; in the outpatient setting, the goal should be a gain of 200 to 500 g per week. Patients should be weighed at the same time regularly in the morning wearing light clothing (CCP).

In everyday clinical routine, the best guide to the appropriate nutrition to give during treatment for anorexia nervosa is body weight (CCP).

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is often accompanied by psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disorders, which can be severe; often these must be regarded as separate conditions and they need to be taken into account in the treatment plan (18). The symptom burden is higher in co-morbid patients and the level of psychosocial functioning more impaired. In diagnosing BN, it is important to obtain data from the life areas listed in Box 5.

Box 5. Diagnostic considerations in patients with bulimia nervosa.

Family history of eating disorders and eating-related behaviors in the family

Patient history of emotional neglect, experience of physical or sexual violence, problems with self-worth, and problems with impulse control, dieting, and excessive preoccupation with their own body (CCP)

Co-morbid psychological disorders, especially anxiety disorders (chiefly social phobia), depression, substance abuse or dependency, and cluster B or C personality disorders

Psychotherapeutic methods have been shown to be effective and are the treatment methods of choice (LOE Ia, GoR A). In relation to the core symptoms—loss of control in eating, and vomiting as the most frequent compensatory behavior—they achieve moderate to large effect sizes (mean reduction by 70%, Cohen’s d = 0.78; or 67%, Cohen’s d = 0.94; post-effect sizes).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for BN (CBT-BN) is the psychotherapeutic method that has been most researched and for which the highest level of evidence exists, and it should therefore be offered to patients with BN as the treatment of choice (LOE Ia, GoR B).

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) shows a comparable efficacy to CBT (ES Ib, GoR B), but is not licensed as an insurance refunded psychotherapy in Germany.

Other psychotherapies are possible if CBT is not available, appears to be ineffective in a particular case, or is not wanted (LOE II, GoR B). Psychodynamic therapy (PT) may be recommended as an alternative (LOE II, GoR 0).

Even in uncomplicated cases of BN, treatment should last for at least 25 sessions at a frequency of 1 therapy session per week (GoR CCP). In more complex cases or those with more extensive psychological co-morbidity, much longer treatment is necessary (GoR CCP). Self-help programs have long been under discussion as an alternative to existing psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic treatments, sometimes in the context of “stepped care models.” Most of them are based on therapy manuals that contain the essential elements of CBT. The effects of self-help programs are smaller than those of the psychotherapies, but have nevertheless been clearly demonstrated (eating binges reduced by 57%, Cohen’s d = 0.68; vomiting reduced by 50%, Cohen’s d = 0.21). For some patients, a guided self-help program may be sufficient therapy.

In the pharmacotherapy of BN, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) represent the first choice of drug therapy in terms of symptom reduction, adverse effects profile, and patient acceptance (LOE Ia, GoR B). However, the efficacy of SSRIs on the core symptoms of BN is relatively weak (binge eating: Cohen’s d = 0.22; vomiting: Cohen’s d = 0.18). In Germany, the only substance licensed for the treatment of BN is fluoxetine in combination with psychotherapy, and then only in adults (LOE Ia, GoR B). The effective dose of fluoxetine in BN is 60 mg/day (LOE Ib, GoR B). Any attempt at treatment should be for not less than 4 weeks. If treatment is successful, it should be assumed that it should be continued for some time (GoR CCP) (Box 6).

Box 6. Recommendations for treatment of bulimia nervosa.

Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for bulimia nervosa (BN).

Treatment should be symptom-oriented according to the disorder (clinical consensus point [CCP]).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is regarded as the treatment of choice in children, adolescents, and adults.

Treatment should last for at least 25 sessions at a frequency of at least 1 session per week (CCP).

In bulimia patients with co-morbidities, e.g., borderline symptoms, treatment should be enhanced with further disorder-adapted therapeutic elements (CCP).

In the case of children and adolescents with BN, family members should be involved in the treatment (CCP).

For some patients with BN, an evidence-based self-help program carried out under guidance (guided self-help) and based on elements of CBT may represent adequate treatment (B, level of evidence Ia).

Administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is the drug therapy of choice. In Germany, only fluoxetine in combination with psychotherapy is licensed for use in adults with BN (B, level of evidence Ia).

Binge eating disorder

The aim of most patients with BED is usually to receive treatment for their co-existing obesity, i.e., they want to lose weight. This desire must be taken into account in the treatment or treatment plan for BED and must be carefully discussed with the patient. The various aspects of the therapeutic goals are shown in eBox 4.

eBox 4. Treatment goal in binge eating disorder.

Treating the symptoms of binge eating disorder (BED) (bingeing, any overweight/obesity, eating-disorder-specific psychopathology)

Treating any other existing psychological complaints (e.g., problems with self-worth and shame; regulation of affect)

Treating co-morbid psychological disorders (e.g., depression, social phobia)

Preventing relapse (communication of meta-knowledge)

Psychotherapeutic studies of BED are mainly based on CBT, a few of them on IPT. While BED-adapted CBT (CBT-BED) in particular is very effective in terms of symptoms, i.e., on the frequency of bingeing or the number of days with binges (d = 0.82–1.04; LOE Ia, GoR A), only small effects are shown in terms of weight loss. More recent studies have also shown IPT to be effective (LOE Ib) (19). Interventions on the basis of guided self-help manuals largely correspond to those of CBT-BED. The interventions are classified as highly effective in terms of reduction of the frequency of bingeing (d = 0.84; LOE Ib, GoR B). In terms of weight reduction, however, no effects are seen here either. As a proviso, it needs to be said that the number of studies on self-help is small.

In Germany, no drug is officially licensed for the treatment of BED (off-label use). Patients with BED who receive antidepressants (tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) and anticonvulsants (topiramate and zonisamide) had higher remission rates for binge eating frequency than those who received placebo (d = 0.52; LOE Ia, GoR B), and co-morbid depressive symptoms also improved (20, 21). In a few studies weight reduction is seen with certain drugs, but the dropout rate is very high (20, 21).

Combining drug therapy with CBT does not lead to additional effects in terms of the symptoms of the eating disorder, but has small effects for weight loss. CBT-BED appears to be superior to pure pharmacotherapy (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine) (21, 22). Obese patients with BED appear to benefit from weight reduction programs as much as obese patients without BED (LOE Ib) (23). BED-adapted CBT shows no extra effects on weight compared with ordinary, conservative weight reduction measures, which as a rule also contain treatment elements from behavioral therapy (5, 23, 24) (LOE Ib–IIb). Although more recent studies were unable to show a correlation between calorie-restrictive nutrition (hypocaloric diet) and exacerbation of BED symptoms (LOE IIa, IIb) (25), it ought at least to be investigated whether BED is regularly preceded by dieting. As in BN, it does not appear to be sensible to recommend restrictive eating behavior, with the aim of losing weight, and undertaking treatment for BED at the same time. The criteria for inpatient treatment for BN and BED are listed in Box 7.

Box 7. Indication criteria for inpatient treatment for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

Insufficient change during outpatient treatment

Failure of outpatient or day patient treatment

Absence of adequate outpatient care facilities near the patient’s home

Extensive psychological and physical co-morbidity (e.g., self-harm, type I diabetes mellitus) that necessitates close monitoring by a physician

Severe disease (e.g., poor motivation, strong habituation of symptoms, very chaotic eating behavior)

Significant conflict in the social and family environment

Suicidal tendencies

Requirement for treatment by a multiprofessional team with hospital-type treatment methods (inpatient intensive care)

The S3 guideline is accessible on the AWMF website: www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/051–026.html.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Professor Herpertz has received lecture fees from Lilly, Lundbeck and Pfizer.

Dr. Hagenah has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca and Medice.

Dr. Vocks, Prof. von Wietersheim, Dr. Cuntz and Prof. Zeeck declare that no conflict of interest exists.

The authors of this article wish to thank the following for their commitment, for helping to organize the expert meetings, for moderating, and for their contributions to discussions, all of which contributed to the successful completion of this guideline: Prof. Ina Kopp (AWMF), for moderating the consensus meeting for the S3 Guideline on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Eating Disorders; Kristiane Göpel, Tübingen (VAKJP); Timo Harfst, Berlin (BPtK); Dr. Claus-Dieter Munz, Stuttgart (DGPT); Prof. Günter Reich, Göttingen (DGPT); Dr. Ingo Spitzczok von Brisinski, Viersen (BKJPP); Dr. Wally Wünsch-Leiteritz, Bad Bevensen (BFE).

References

- 1.Fichter MM. Epidemiologie der Essstörungen. In: Herpertz S, de Zwaan M, Zipfel S, editors. Handbuch Essstörungen und Adipositas. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (1992) Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zipfel S, Löwe B, Reas DL, Deter HC, Herzog W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2000;26:721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keel PK, Mitchell JE, Miller KB, Davis TL, Crow SJ. Long-term outcome of bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:63–69. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association (APA) 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Mussell MP, Raymond NC, Seim HC, Specker SM, Crosby RD. Short-term cognitive behavioral treatmen does not improve long-term outcome of a comprehensive very-low-calorie diet program in obese women with binge eating disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Nugent S, Mussell MP, Crow S J, Thuras P. Self-help versus therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder at follow-up. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:363–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basdevant A, Pouillon M, Lahlou N, Le Barzic M, Brillant M, Guy-Grand B. Prevalence of binge eating disorder in different populations of French women. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18:309–315. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199512)18:4<309::aid-eat2260180403>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spitzer RL, Yanowki SZ, Wadden T, Wing R. Binge eating disorder: its further validation in a multisite study. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 1):51–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas L, Stargardt T, Schreyoegg J, Schlösser R, Danzer G, Klapp BF. Inpatient costs and predictors of costs in the psychosomatic treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2011 doi: 10.1002/eat.20903. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krauth C, Buser K, Vogel H. How high are the costs of eating disorders - anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa - for German society? Eur J Health Econ. 2002;3:244–250. doi: 10.1007/s10198-002-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute of Clinical Excellence Eating Disorders. London: British Psychological Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2004. National Clinical Practice Guideline No CG6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Disorders, revised. New York: American Psychiatric Association; 2006. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, Herpertz S. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:205–217. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann A, Weber S, Herpertz S, Zeeck A. Psychological Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa. A Meta-Analysis of Standardized Mean Change Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80:216–226. doi: 10.1159/000322360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean change measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1988;41:257–278. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson-Brenner H, Eddy K, Franko D, Dorer D, Vashchenko M, Herzog D. Personality pathology and substance abuse in eating disorders: a longitudinal study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:203–208. doi: 10.1002/eat.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments for Binge Eating Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefano SC, Bacaltchuk J, Blay SL, Appolinário JC. Antidepressants in short-term treatment of binge eating disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Behav. 2008;9:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Bertelli M. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behaviour therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:298–306. doi: 10.1159/000056270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wonderlich SA, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Peterson C, Crow S. Psychological and dietary treatments of binge eating disorder: conceptual implications. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:58–73. doi: 10.1002/eat.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadden TA, Foster GD, Sarwer DB, Anderson DA, Gladis M, Sanderson RS. Dieting and the development of eating disorders in obese women: results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J of Clin Nutr. 2004;80:560–568. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munsch S, Biedert E, Meyer A, Michael T, Schlup B, Tuch A. A randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss treatment for overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(2):102–113. doi: 10.1002/eat.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]