Various functions have been proposed for the 40–50 independent origins of bioluminescence across the tree of life—for example, mate recognition, prey attraction, camouflage, and warning coloration [1]. Millipedes in the genus Motyxia produce a greenish-blue bioluminescence at a wavelength of 495 nm that can be seen in darkness [2]. These detritivores are chemically defended by cyanide, which they generate internally and discharge through lateral ozopores [3]. Motyxia are blind, and thus provide an ideal model system to investigate the ecological role of bioluminescence since discrimination of their visual appearance is limited to other organisms, for example predators. Detailed studies have been made of the biochemical mechanisms underlying Motyxia bioluminescence [2, 4]. In contrast, the adaptive significance of the bioluminescence in these millipedes remained unknown [5, 6]. We show that bioluminescence has a single evolutionary origin in millipedes and it serves as an aposematic warning signal to deter nocturnal mammalian predators. Contrary to the intuitive expectation that luminescence might attract curious predators, we obtained strong experimental evidence in field trials that luminescence deters predation attempts, with living and artificial non-luminescent millipedes being attacked up to four times more often than their luminescent counterparts. Among the numerous examples of bioluminescence, this is the first field experiment in any organism to demonstrate that bioluminescence functions as a warning signal.

Aposematic colors warn predators of distasteful or unpleasant qualities, such as spines, venoms, or chemical explosions [7]. When disturbed, blind millipedes in the order Polydesmida generate a toxin by means of a cyanohydrin reaction in which a stable precursor, mandelonitrile, is enzymatically converted into hydrogen cyanide [3]. Many diurnal species display aposematic coloration in yellow, orange, or red [8]. In contrast, those in the genus Motyxia (= Luminodesmus) are nocturnal and do not display conspicuous color in daylight. Instead, Motyxia species are bioluminescent, producing a greenish-blue light that gradually intensifies when the millipede is disturbed (Fig. 1A, B). Currently, 8 species of luminescent millipedes are known among the 12,000 millipede species that have been described [5, 6]. The 8 species comprise a single clade and are globally restricted to 3 counties in California [Figure S1, Supplemental Information]. Light from Motyxia originates in the exoskeleton and involves a photoprotein that contains a chromophore with porphyrin as its functional group [2, 4]. The basic photogenic mechanism is more similar to that of the GFP-jellyfish, Aequorea victoria, than that of the more closely-related firefly Photinus pyralis [4]. Nevertheless, the structure of the luminescent molecules remains unknown and their homologies to molecules of other animals are uncertain [2, 4]. Several hypotheses for the function of bioluminescence in Motyxia have been suggested. One hypothesis states that luminescence serves as an aposematic signal, warning would-be predators of its noxiousness [6]. It has also been suggested that the bioluminescence serves no function at all [5], or even that it inadvertently attracts predators. Until now, these competing hypotheses have not been tested.

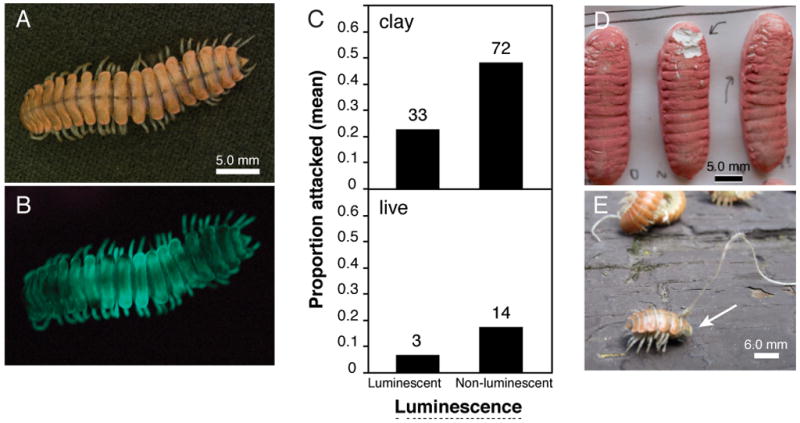

Figure 1.

Luminescent millipede and results of the field experiment. A. Motyxia sequoiae photographed in natural light, and B. entirely with light from luminescence; C. Mean proportion of millipedes attacked versus luminescence. Number of individuals attacked above bars; D. Rodent incisor marks in clay millipede, E. Live millipede (arrows) with anterior segments 1 – 14 missing. (Phylogeny of Motyxia species and close relatives in Supplemental Information online, Figure S1)

We used live and clay model millipedes in field trials (where Motyxia naturally occur in California) to test the prediction that luminescent individuals are attacked less often than non-luminescent individuals. We collected 164 living millipedes of the species Motyxia sequoiae from Giant Sequoia National Monument in California, and painted the surface of half (82 individuals) with paint to conceal their bioluminescence. Using polymer clay, we also constructed 300 clay millipedes from a bronze cast of M. sequoiae. Clay models were covered with the same paint, and in half, a chemiluminescent pigment was mixed into the paint to generate luminescence. To capture the naturally patchy distribution of indigenous predators, we distributed living and model millipedes along separate transects, with a random distribution of luminescent and non-luminescent millipedes spaced five meters apart. Experiments were run over night, after which predation marks among luminescent and non-luminescent groups were tallied and statistically analyzed to evaluate the null hypothesis of parity between treatments.

As predicted, significantly more of the non-luminescent millipedes (both clay and live) were attacked than luminescent millipedes (Fig. 1C – E). Nearly half (48.6%) of the non-luminescent clay millipedes were attacked, while only 22.4% of the luminescent models were attacked. Experiments conducted with live millipedes exhibited a similar attack pattern. Nearly one-fifth (17.9%) of the non-luminescent live millipedes were attacked as opposed to only 4.0% of the luminescent individuals. The asymmetrical attack ratios between luminescent and non-luminescent groups differed significantly from the null hypothesis of a one-to-one ratio for clay millipedes (G-test, G = 14.839, 1 df, P < 0.001; exact binomial test P < 0.001) and for live millipedes (G = 7.723, 1 df, P = 0.005; exact binomial test P = 0.013). Rodents were found to inflict most of the predation marks, as indicated by oppositional incisor impressions on the clay surface (Fig. 1D). Most nocturnal rodents can detect millipede luminescence by way of scotopic (night) vision, as a result of a reflective tapetum and a high density of rod photoreceptor cells in the retina [9]. While surveying the experiment site, small neotomine rodents, likely the southern grasshopper mouse (Onychomys torridus), were observed to be active nocturnally.

Our results demonstrate strong predatory avoidance of luminescent coloration, results which are inconsistent with the expectation that a luminescent object would attract nocturnal predators and initiate exploratory sampling. We found that non-luminescent millipedes were attacked more than twice as often. Thus, our experimental evidence indicates luminescence serves an aposematic function of deterring predators. Aposematism involves two main qualities: noxiousness and a signal of noxiousness. By using actual live millipedes in conjunction with clay models, our experiment indicates that these two main qualities (noxious chemical defense and luminescent signal), even when treated separately, function to deter predator attacks. With our clay model experiment, we demonstrate that luminescence in and of itself, and no other cue such as odor or taste repels predators. The live millipede data show that a luminescent millipede does not repel attack as well if the light is concealed. (Luminescent millipedes were attacked four times less often than their non-luminescent counterparts.) This finding suggests that visual luminescent cues are sufficient to deter predation. However, non-visual cues such as olfactory and gustatory (e.g., from chemical defenses in live millipedes), though not directly compared against luminescence, also contribute to Motyxia aposematism. How much more protection is conferred by the combinatory effect of visual plus non-visual cues is uncertain, and how predators come to recognize Motyxia bioluminescence as an indication of their cyanogenic-based noxiousness remains unclear. As with aposematic signals generally, the response to the signal may reflect avoidance learning, dietary conservatism (including neophobia), and/or unlearnt avoidance that evolved in predator populations [10]. Future work to investigate how predators develop an avoidance of Motyxia is of considerable interest. A simple follow-up would be to repeat the experiment in a similar habitat outside the geographical range of bioluminescent millipedes. If allopatric predator populations similarly avoided bioluminescent millipedes, it might suggest that avoidance is rooted in neophobia, or a prior evolutionary association with bioluminescent millipedes that led to unlearnt avoidance. If predator populations in allopatry do not avoid bioluminescent millipedes, then it would suggest there has been coevolution between predators and millipedes, which would provide a basis for future investigations into whether learning is involved. Bioluminescence in Motyxia provisionally represents an adaptive innovation, which is particularly impressive in terms of the small geographic and evolutionary scale at which it appears to have occurred.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We show that bioluminescence has a single evolutionary origin in millipedes

Of 12,000 millipede species described, only 8 Californian species emit light

Our field experiment demonstrates that bioluminescence repels predation attempts

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a U.S. National Institutes of Health Training Grant to the Center for Insect Science at the University of Arizona (2 K12 GM000708) and a U.S. National Science Foundation Phylogenetic Systematics grant to Paul Marek (DEB-1119179). We thank Charity Hall for casting the bronze millipede. Roland Himmelhuber and Bree Gomez assisted with measuring bioluminescence. David Maddison, Annie Leonard, Rick Brusca, Michael Nachman, Wallace Meyer, and two anonymous reviewers contributed critical discussion. Kojun Kanda, Mary Jane Epps, Rob Marek, and Eric O’Donnell provided field assistance. Robin Galloway of Giant Sequoia National Monument, Steve Anderson of Sequoia National Forest, and Harold Warner of Sequoia National Park provided essential logistical support and permissions to conduct the experiment.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes detailed experimental procedures and the phylogeny of Motyxia species and close relatives (Figure S1). It can be found with this article online at doi: XXXXXX.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haddock SHD, Moline MA, Case JF. Bioluminescence in the sea. Annu Rev Mar Sci. 2010;2:443–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120308-081028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastings JW, Davenport D. The luminescence of the millipede, Luminodesmus sequoiae. Biol Bull. 1957;113:120–128. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisner T, Eisner HE, Hurst JJ, Kafatos FC, Meinwald J. Cyanogenic glandular apparatus of a millipede. Science. 1963;139:1218–1220. doi: 10.1126/science.139.3560.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimomura O. Porphyrin chromophore in Luminodesmus photoprotein. Comp Biochem Phys B. 1984;79:565–567. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Causey NB, Tiemann DL. A revision of the bioluminescent millipedes in the genus Motyxia (Xystodesmidae: Polydesmida) Proc Am Philos Soc. 1969;113:14–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shelley RM. A re-evaluation of the milliped genus Motyxia Chamberlin, with a re-diagnosis of the tribe Xystocheirini and remarks on the bioluminescence (Polydesmida: Xystodesmidae) Insecta Mundi. 1997;11:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poulton EB. The Colours of Animals: Their Meaning and Use, Especially Considered in the Case of Insects. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1890. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marek PE, Bond JE. A Müllerian mimicry ring in Appalachian millipedes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9755–9760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solovei I, Kreysing M, Lanctôt C, Kösem S, Peichl L, Cremer T, Guck J, Joffe B. Nuclear architecture of rod photoreceptor cells adapts to vision in mammalian evolution. Cell. 2010;137:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruxton GD, Sherratt TN, Speed MP. Avoiding Attack: The Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Warning Signals, and Mimicry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.