Abstract

Although community development and social change are not explicit goals of community-oriented primary care (COPC), they are implicit in COPC’s emphasis on community organization and local participation with health professionals in the assessment of health problems. These goals are also implicit in the shared understanding of health problems’ social, physical, and economic causes and in the design of COPC interventions.

In the mid-1960s, a community health center in the Mississippi Delta created programs designed to move beyond narrowly focused disease-specific interventions and address some of the root causes of community morbidity and mortality.

Drawing on the skills of the community itself, a selfsustaining process of health-related social change was initiated. A key program involved the provision of educational opportunities.

EARLY IN HIS CAREER, THE distinguished social epidemiologist John Cassel worked for a time as clinical director of the Pholela Health Center, the pioneering South African program at which Sidney and Emily Kark and their colleagues first created and implemented communityoriented primary care (COPC). Their work transformed the health status of an impoverished rural Zulu population and, ultimately, served as a worldwide model for the integration of clinical medicine and public health approaches to individuals and communities.1–4 During a window of opportunity that opened in the 1950s, Pholela’s center and a network of other South African health centers elaborated the core goals of COPC: epidemiological assessment of demographically defined communities, prioritization, planned interventions, and evaluation.5 By decade’s end, however, these centers had all been shut down by a rigidly racist apartheid government.

A few years later, Dr Cassel—by then a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Public Health—made a return visit to a Pholela that was even more deeply impoverished. After conducting a thoroughly informal and anecdotal survey, he saw no signs that the earlier improvements in health status had persisted. But he was struck by the target population’s unusually high levels of educational aspiration and educational achievement. (Indeed, one of the health center’s pediatric patients later went on to become a physician, a leader of the African National Congress in exile, and—after liberation—Nelson Mandela’s first minister of health.6)

Cassel’s observation illustrates a goal of COPC—community development—that the Karks, fully aware that social, economic, and environmental circumstances are the most powerful determinants of population health status, understood very well. Although only occasionally specified in their publications, it was implicit in their programs focusing on community organization and involvement, training and development of local residents as staff members, employment of Zulu nurses as role models, intensive health education, and environmental improvements. Even in the constrained social and political circumstances of apartheid-era South Africa, such efforts apparently had a lasting educational effect.

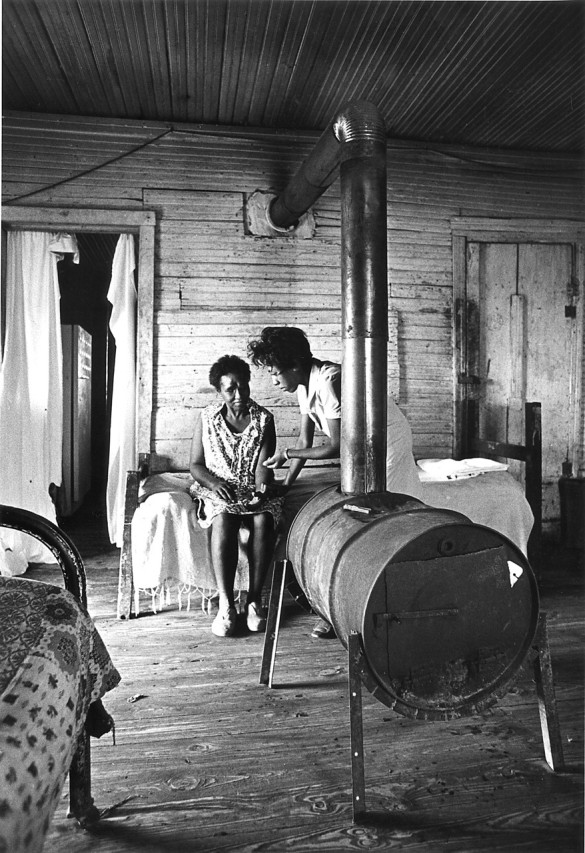

Figure.

A health center nurse makes a home visit to a stroke-disabled patient living in a plantation shack near Shelby in Bolivar County, Mississippi, in 1967. Most such housing is less substantial than this. (Photo by Dan Bernstein.)

In the mid-1960s, half a world away, another—and much bigger—window of opportunity opened in the United States. The “war on poverty” and its federal implementing agency, the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), proposed in principle to address the root causes of deprivation and inequality. The OEO’s largest arm, the Community Action Program, was committed to ideas of community involvement and program participation. Of equal importance, the flourishing civil rights movement embodied bedrock principles of community empowerment and political and economic equity. When health services—and, specifically, COPC-based health centers—were added to this rich mix, the stage was set for an experimental test of the idea that a health program, in addition to its traditional curative and preventive roles, could be deliberately fashioned as an instrument of community development and as a lever for social change.

This experiment was conducted, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Tufts Medical School proposed the community health center model to OEO. The Tufts-Delta Health Center was the first in what is now a national network of more than 900 federally qualified health centers. Closely modeled on the Pholela experience,7 it was designed to serve a primarily African American population of 14 000 persons residing in a deeply impoverished 500-square-mile area of northern Bolivar County in the Mississippi Delta. As was the case with many other areas of the cotton-growing delta, this was a population of sharecroppers increasingly displaced by mechanization and living in crumbling wooden shacks with no protected water supplies, untouched by food stamps or commodity surplus foods. These families had a median income of less than $900 per year, had a median level of education of 5 years (and were exposed to segregated and inferior schools), and were suffering the inevitable consequences of malnutrition, infant mortality, infectious and chronic diseases, and adult morbidity and mortality.

Figure.

A typical plantation shack near Alligator, Mississippi, in 1968. A whole generation is often missing from the home, as parents—displaced by mechanical cotton-harvesting—leave children with grandparents while they search for other work in northern cities. (Photo by Dan Bernstein.)

Detailed descriptions of the Tufts-Delta Health Center’s personal medical service programs, outreach services, health education efforts, and environmental and other interventions involving housing, water supplies and sanitation, and other public health approaches have been published elsewhere.8,9 What is of interest here is the center’s community empowerment program.

With the guidance of Dr John Hatch, the head of the center’s community organization department, 10 local health associations were formed and began to survey and assess local needs, nominate people for employment at the center, and plan satellite centers. Each association elected a representative to an overarching organization, the North Bolivar County Health Council. The council served as the health center’s required community advisory board but was deliberately chartered as a nonprofit community development corporation to broaden the scope of its work.

Its first effort was to end the local racist banking custom that denied mortgages to Black applicants altogether, demanded a White cosigner, or charged exorbitant (and illegal) under-the-table interest rates. Members of the health council visited all of the local banks and informed them that the center’s million-dollar annual funding and cash flow would be deposited in whichever bank opened a branch in a Black community, hired residents as tellers instead of janitors, and engaged in fair mortgage loan practices.

After successful completion of this process, the local health associations obtained mortgages to buy buildings for satellite centers, rented them to the health center during the day, used the rental income to cover the loan payments, and used the buildings as community centers at night. Local health center staff members obtained mortgages to build modest new homes. Next, because there was no public transportation and few people had cars, the health council—on contract from the health center—established a bus transportation system that linked the satellites to the health center (and provided economic mobility for workers and shoppers).

This was just the beginning. Subsequently, the council developed a pre–Head Start early childhood enrichment program and a nutritional and recreational program for isolated elderly rural residents. In addition, the council hired a part-time lawyer to ensure that federal and state agencies (which had often ignored Black communities) provided equitable assistance in housing development, recreational facilities, water systems, and other elements of physical infrastructure.

Also, by means of a federal grant and its own budget, the health council developed a supplemental food program. And when staff of the health center suggested that local residents grow vegetable gardens, the council had a better idea: with a foundation grant and help from the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, it spun off a new nonprofit organization, the North Bolivar County Farm Co-op, in which a thousand families pooled their labor to operate a 600-acre vegetable farm and share in the crops. This unique enterprise—nutritional sharecropping—built on the agricultural skills people already possessed.

What made all of this possible? One of the principal factors was ending the isolation that had kept members of poor rural minority communities cut off from knowledge of, or help from, such traditional sources of support as government agencies, philanthropic foundations, and universities and professional schools. By 1970, for example, the health council and health center had ties to 7 universities, a medical school, and numerous foundations and agencies. In addition, in the summer of 1970 alone, the programs were host to Black and White student interns from 8 medical schools, 2 nursing schools, 3 schools of social work, 2 public health schools, and 3 environmental health programs.

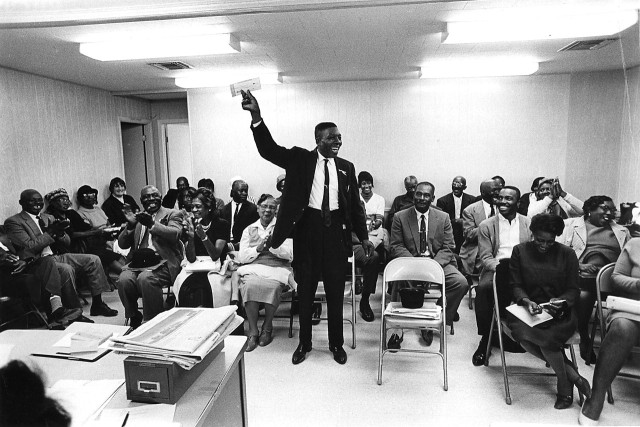

Figure.

At a 1968 meeting of the North Bolivar County Health Council at the Delta Health Center, Mound Bayou, Mississippi, William Finch announces the arrival of a Ford Foundation check that will launch a farming cooperative to grow vegetables for a malnourished population. (Photo by Dan Bernstein.)

As was the case at Pholela, however, the most important impact was educational, in this instance in the form of a structured and multifaceted program. The health center established an office of education, seeking out bright and aspiring local high school and college graduates, assisting them with college and professional school applications, and providing scholarship information and university contacts. At night, health center staff taught high school equivalency and college preparatory courses, both accredited by a local Black junior college. In the first decade in which it was in place, this effort produced 7 MDs, 5 PhDs in health-related disciplines, 3 environmental engineers, 2 psychologists, substantial numbers of registered nurses and social workers, and the first 10 registered Black sanitarians in Mississippi history.

One of the physicians returned to become the center’s clinical director, and another returned as a staff pediatrician. A sharecropper’s daughter acquired a doctorate in social work and a certificate in health care management and returned as the center’s executive director. (Her successor 8 years later, similarly well credentialed, had once been a student in the college preparatory program.) Other center staff members completed short-term intensive training as medical records librarians, physical therapists, and laboratory technicians.

Moreover, as John Cassel’s observation at Pholela suggested, this process has proved to be selfperpetuating. Today, the number of Black northern Bolivar County residents and their next-generation family members working in healthrelated disciplines, at every level from technician to professional, is well over 100. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that other health centers, even without special programs of this sort, may have a similar effect. Local residents who become center staff members tend to invest their increased earnings in two areas: better housing and college education for their children.

The effect is more than economic, however. Building community-based institutions and replacing the race-and class-based isolation of poor and minority communities with ties to other institutions in the larger society may create a new kind of social capital that facilitates social change. This in turn enlarges the health effects of the traditional clinical and public health interventions that are the core of COPC. Other community health centers established in the first wave of the OEO’s Office of Health Affairs program similarly invested vigorously in community organization, environmental change, and (in urban areas with more existing resources) links with other organizations to create multisectoral interventions.

There are two important lessons to be gained from the Mississippi Delta experience. The first is that communities of the poor, all too often described only in terms of pathology, are in fact rich in potential and amply supplied with bright and creative people. The second is that health services, which have sanction from the larger society and salience to the communities they serve, have the capacity to attack the root causes of ill health through community development and the social change it engenders.

As at Pholela, after too few years the window that was open to expanded programs and community development began to close. This happened in part because of program costs and in larger measure because conservative national administrations were (to put it mildly) not overly interested in community empowerment and social change. As a result, health center programs were squeezed back toward more traditional roles of delivering personal medical services and more limited public health interventions.

Good ideas, however, may be rediscovered, and the potential is still there. The North Bolivar County Health Council, no longer in need of university sponsorship, now owns and operates the freestanding Delta Health Center, with branches in 2 additional counties, and most other federally qualified health centers have analogous community control and practice elements of COPC. Over the next few years, the number of community health centers will double. The recent and growing national interest in community–campus partnerships, including but not limited to health services, may be a first step in the rediscovery of community development as a legitimate goal of health care interventions.

Peer Reviewed

References

- 1.Kark SL, Cassel J. The Pholela Health Centre: a progress report. S Afr Med J. 1952;26:101–104, 131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uach D, Tollman SM. Public health initiatives in South Africa in the 1940s and 1950s: lessons for a post-apartheid era. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1043–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susser M. A South African odyssey in community health: a memoir of the impact of the teachings of Sidney Kark. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1039–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philips HT. The 1945 Gluckman report and the establishment of South Africa’s health centers. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1037–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kark SL, Steuart G, eds. A Practice of Social Medicine. Edinburgh, Scotland: E & S Livingstone Ltd; 1962.

- 6.Geiger HJ. A piece of my mind. The road out. JAMA. 1994;272:1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geiger HJ. Community-oriented primary care: the legacy of Sidney Kark. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:946–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geiger HJ. The meaning of community-oriented primary care in the American context. In: Connor E, Mullan F, eds. Community Oriented Primary Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1982:73–114.

- 9.Geiger HJ. A health center in Mississippi: a case study in social medicine. In: Corey L, Saltman SE, Epstein MF, eds. Medicine in a Changing Society. St. Louis, Mo: CV Mosby Co; 1972:157–167.