Abstract

The overall goal of this study was to assess the longitudinal changes in bone strength in women reporting rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n=78) compared to non-arthritic control participants (n=4,779) of the Women's Health Initiative Bone Mineral Density sub-cohort. Hip structural analysis program was applied to archived dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scans (baseline, years 3, 6, and 9) to estimate bone mineral density (BMD) and hip structural geometry parameters in three femoral regions: narrow neck, intertrochanteric and shaft. The association between RA and hip structural geometry was tested using linear regression and random coefficient models (RCM). Compared to the non-arthritic control the RA group had a lower BMD (p=0.061) and significantly lower outer diameter (p=0.017), cross-sectional area (p=0.004), and section modulus (p=0.035) at the narrow neck region in the longitudinal models. No significant associations were seen at the intertrochanteric or shaft regions, and the association was not modified by age, ethnicity, glucocorticoid use, or time. Within the WHI-BMD, women with RA group had reduced BMD and structural geometry at baseline, and this reduction was seen at a fixed rate throughout the nine years of study.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Hip Structural Geometry, Osteoporosis, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a multi-system disorder characterized by chronic destructive synovitis, associated with substantial adverse health consequences (1). Osteoporosis, a major public health concern for aging populations, is one of the common adverse health consequences seen in RA (2). Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD), and significant decreases in BMD are correlated with increases in fracture risk (3–6). RA patients have lower BMD than non-arthritic comparison populations (7–9), and this decrease in BMD subsequently increases the risk for a variety of osteoporotic fractures (10, 11).

The mechanism of fracture in RA populations has been under investigation for several years. Molecular factors including inflammatory cytokines such as, interleukin (IL) – 1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, have direct and indirect effects on osteoclasts, increasing bone resorption (12). Glucocorticoids, a class of common therapeutic agents used in RA, have known effects on calcium absorption and bone remodeling (13, 14), and are associated with increased risk for fractures (15). General lifestyle and demographic osteoporosis risk factors, such as age, smoking, and physical activity play a significant role in fracture risk (16), and have been considered as covariates in a variety of RA and fracture studies.

As stated by Griffith and Genant, osteoporotic fractures occur “when bone strength is less than forces applied to the bone” (17). Bone strength is comprised of both the material properties, including mineralization density and collagen composition, and structural properties, including architecture and geometry (18). Because low BMD is strongly correlated with increased fracture risk, BMD is commonly measured as a marker of bone strength; although it is not a direct measure of either structural geometry or tissue material properties.

Beck and colleagues developed a hip structural analysis (HSA) program that utilizes dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) images to extract limited structural parameters. This is particularly advantageous to clinical and research practice as DXA is the method routinely used in the assessment of BMD. The HSA program has been used in a variety of studies, and significant improvements in hip structure have been observed with the use of a variety of agents used in the treatment of osteoporosis such as raloxifene (19), teriparatide (20), postmenopausal hormone therapy (21, 22), bisphosphonates (23), and denosumab (24), and modest benefit from calcium and vitamin D supplementation (25, 26) when compared to age-matched control or placebo groups.

To date, there have been no hip structure studies in RA populations. It is possible that the risk factors associated with low BMD in RA also have a negative effect on structural geometry, which could further increase the risk for fracture in this population. Structural instability has been observed in hip fracture cases compared to controls using HSA (27, 28), and recently LaCroix and colleagues found that outer diameter width at the intertrochanteric region was independently associated with hip fracture risk (29), highlighting the importance of having structural measures in the examination of fracture risk, as there are no non-invasive methods for measuring bone material properties. This epidemiologic investigation assessing the structural dynamics of bone over time may provide information on the role of hip structure in fracture risk in postmenopausal women with RA. The objectives of this study are to: 1) assess the longitudinal changes in hip structural geometry in RA compared to non-arthritic controls, and 2) test if age, ethnicity, time, or glucocorticoid use alters the association between RA and hip structural geometry in a population of postmenopausal women from the Women's Health Initiative.

METHODS

Women's Health Initiative (WHI)

This study was performed in participants of the Women's Health Initiative Bone Mineral Density (WHI-BMD) centers. The WHI is a nationwide study that investigated the risk factors and preventive strategies of the major contributors to morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women: including heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and osteoporotic fractures (30). The WHI recruited 161,808 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 from 40 centers across the country to participate in the clinical trials (CT) component; including the hormone therapy trials (HT), dietary modification trial (DM), and the calcium and vitamin D trial (CaD); or the observational study (OS). Details of recruitment strategies and baseline participant information have been previously published (31).

Three clinical centers (Tucson/Phoenix, AZ; Birmingham, AL; and Pittsburgh, PA) comprised the BMD sub-cohort. Women enrolled in these centers (n=11,020) had DXA scans on a Hologic QDR 2000 or 4500W machine (Bedford, MA ) to measure bone density at the spine, areal hip, and total body; in addition to whole body and regional body composition. The scans were completed at baseline, years 3, 6, and 9 for participants of the OS; and baseline, years 1, 3, 6, 9, and closeout of the study for CT participants. All participants gave signed consent to participate in the WHI study, and the current study was approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board.

Defining Rheumatoid Arthritis Status

The WHI health assessment form was used to identify arthritis status at baseline. The participants were asked, “Did your doctor ever tell you that you have arthritis?” with responses of yes or no. The participants answering “no” were placed in the non-arthritic control group. Women responding “yes” were then asked “What type of arthritis do you have?” with responses of “rheumatoid arthritis” and “other” or “do not know”. Using the methodology of Walitt and colleagues (32), the RA group was defined to include those women who self-reported RA and one or more of the following commonly used anti-rheumatic agents at baseline including: methotrexate, gold, biologic anti-TNF agents, leflunomide, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, hydroxychloroquine, minocycline, sulfasalazine, and glucocorticoids. Non-responders, those answering “other/do not know”, those self-reporting RA without medications, and those not responding to the follow-up arthritis question were excluded.

Assessing Hip Strength using Hip Structural Analysis

The outcome of this study, the structural geometry of the proximal femur, was ascertained using the hip structural analysis (HSA) program. The HSA program was applied to the archived DXA (baseline, years, 3, 6, and 9) scans to produce estimates of bone strength at three femur cross-sections; the narrow neck (NN), intertrochanteric (IT), and shaft (S). Details on the specifics of HSA have been previously published (33), but in summary, the HSA program computes at each of the 3 cross-sections: conventional BMD, bone cross-sectional area (CSA) bone outer diameter (OD), the center of mass of each cross-section, and the section modulus (SM). Section modulus is an index of bending strength of a cross-section. Femur neck length, and neck-shaft angle are measured, and estimates of cortical thickness at each cross-section is used for an estimate of buckling ratio. Buckling ratio is an index of susceptibility to local cortical buckling under compressive loads and has been shown to be elevated in hip fracture cases (27, 28).

DXA Quality Control

The WHI center at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF Prevention Sciences, San Francisco, CA) served as the BMD quality control center, which included monitoring DXA operator performance, DXA machine performance, and managing DXA databases from the three WHI clinic centers. Three Hologic spine, hip, and linearity phantoms were exchanged among the centers to assess quality control and cross-calibration. For the structural measurements, a separate cross-calibration was conducted using a special phantom designed for the HSA method. Sensitivity of HSA was not examined in this study, however, previous studies using the program have found moderate to good reliability with coefficient of variations ranging from 0.8% to 7.2% (34, 35).

Covariates

Variables potentially related to RA, BMD or to hip structural geometry were assessed as covariates. These variables included: age, ethnicity, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), total body percent lean mass, smoking status, hormone use status, physical activity, physical function dietary energy, total calcium intake, total vitamin D intake, use of certain medications (thiazide diuretic, statins, anti-convulsants, thyroid drugs, proton pump inhibitors, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, estrogens, phenobarbital, and heparin), and variables relevant to the WHI (clinical center, participation in HT or CaD trial). Covariates were assessed at baseline using either questionnaire data (age, ethnicity, smoking, hormone use, physical activity, physical function, nutritional factors, and medications), physical measurements (height, weight, BMI), or DXA derived estimates (percent lean mass).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive variables reported by the two groups (non-arthritic control vs. RA) were compared using t-tests for continuous variables and χ-squared test for categorical variables. The association between RA and hip geometry was tested using both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. For the cross-sectional analysis, the mean age-adjusted BMD and hip structural geometry variables were compared at each time point between the groups using linear regression. Linear mixed effects models (LMM), which incorporate all time observations (baseline, year 3, 6, and 9) in one model, were used to analyze the association between RA and hip strength longitudinally. The random coefficient model (RCM), a type of LMM, was used to control for serial correlation in the data by allowing each subject to have a different slope and intercept estimate fitted as random effects. The base model included the hip geometry measure as the dependent variable and RA status, the baseline measure, and visit as the independent variables. Marginal analyses were performed for each of the covariates, and those with a p-value <0.20 were tested in the full model. Backwards elimination techniques were used to generate the final model, which included all variables p<0.05, any clinically or biologically important variables not meeting the significance level, and variables related to WHI design. The interaction between age, ethnicity, time, and GC use were tested. All analyses were performed in STATA v.10 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

A total of 11,020 women were enrolled in the WHI-DXA cohort. The baseline health assessment questionnaire was completed by 10,858 participants of whom 5,253 women reported not having arthritis, and 5,605 responded yes to the initial arthritis question. Of the self-reported arthritis patients, 584 self-reported RA and 4,348 reported other types of arthritis. After reviewing baseline medication, 83 (14.2%) of the self-reported RA cases also reported at least one of the commonly used anti-rheumatic agents. Baseline hip structural geometry measurements were available for 4,779 of the non-arthritic controls and 78 of the RA cases. Sample size at each study visit and the number of observations used in modeling can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Size and Observation Count by Arthritis Status

| Sample Size at Each Study Visit | ||

|---|---|---|

| No Arthritis |

RA |

|

| Baseline | 4779 | 78 |

| Year 3 | 3834 | 49 |

| Year 6 | 3447 | 38 |

| Year 9 | 1878 | 20 |

|

| ||

| Number of Observations | ||

|

| ||

|

No Arthritis |

RA |

|

| 1 | 741 | 25 |

| 2 | 903 | 19 |

| 3 | 2053 | 22 |

| 4 | 1308 | 14 |

Baseline Characteristics

Significant differences were seen between the two groups in several baseline demographic variables. The RA cases were significantly older than the non-arthritic control group with mean (SD) values of 65.4 (7.5) years compared to 61.7 (7.4) years. The non-arthritic control group was slightly taller (0.60 cm on average) than the RA group, and the non-arthritic control group weighed less (2.5 kg less on average) than the RA group. Ethnicity also varied significantly (p<0.001) between the groups, with a higher percentage of African Americans in the RA group (29%) compared to the non-arthritic group (13%).

There were slight differences in lifestyle factors between groups. The RA group had a higher but non-significant percentage of women currently using postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) than the control group (42.3% vs. 35.3%). There were no significant differences between reports of energy intake, energy expended through physical activity, and intake of vitamin D between groups. Physical function was significantly reduced by RA status (p<0.001). Non-arthritic controls had a mean (SD) physical function score of 85.9 (16.4), whereas RA group had a mean score of 53.8 (25.0). Complete information on baseline demographics by RA status can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics by Rheumatoid Arthritis Status

| No Arthritis |

RA |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value | |

| Participant of Observational Study | <0.001 | ||

| No | 2078 (43.5) | 18 (23.1) | |

| Yes | 2701 (56.5) | 60 (76.9) | |

| Participant of Hormone Trial | 0.118 | ||

| No | 3929 (82.2) | 68 (87.2) | |

| Yes | 850 (17.8) | 10 (12.8) | |

| Participant of CaD Trial | 0.003 | ||

| No | 3676 (76.9) | 71 (91.0) | |

| Yes | 1103 (23.1) | 7 (9.0) | |

| Participant of Dietary Modification Trial | <0.001 | ||

| No | 3277 (68.6) | 69 (88.5) | |

| Yes | 1502 (31.4) | 9 (11.5) | |

| Baseline Age Group | <0.001 | ||

| 50–59 | 2039 (42.7) | 19 (24.4) | |

| 60–69 | 1917 (40.1) | 29 (37.2) | |

| 70–79 | 823 (17.2) | 30 (38.5) | |

| Ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 50 (1.1) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 20 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Black or African-American | 618 (13.0) | 22 (28.6) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 330 (7.0) | 8 (10.4) | |

| White (not of Hispanic origin) | 3728 (78.6) | 46 (59.7) | |

| Baseline HT usage | 0.214 | ||

| Never used | 2370 (49.6) | 33 (42.3) | |

| Past user | 719 (15.1) | 12 (15.4) | |

| Current user | 1688 (35.3) | 33 (42.3) | |

| BMI Category | <0.001 | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 43 (1.0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Normal (18.5 – 24.9) | 1420 (34.1) | 15 (26.8) | |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 1539 (37.0) | 22 (39.3) | |

| Obesity i (30.0 – 34.9) | 764 (18.4) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Obesity ii (35.0 – 39.9) | 283 (6.8) | 6 (10.7) | |

| Extreme obesity iii (>= 40) | 111 (2.7) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Baseline Smoking Status | 0.045 | ||

| Never smoked | 2608 (55.2) | 34 (44.2) | |

| Past smoker | 1695 (35.9) | 39 (50.7) | |

| Current smoker | 420 (9.0) | 4 (5.2) | |

|

NoRA |

RA |

||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 61.7 ± 7.4 | 65.4 ± 7.5 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 161.9 ± 6.4 | 161.3 ± 5.7 | 0.395 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.2 ± 15.5 | 74.7 ± 15.8 | 0.160 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 ± 5.5 | 28.7 ± 5.5 | 0.055 |

| Total Energy Expended per Week (METs) | 12.3 ± 14.6 | 11.7 ± 16.4 | 0.697 |

| Physical Function | 85.9 ± 16.4 | 53.8 ± 25.0 | <0.001 |

| Dietary Energy (kclas) | 1644.1 ± 836.3 | 1539.8 ± 717.2 | 0.274 |

| Total Calcium (mg) | 1087.7 ± 707.6 | 1198.1 ± 915.6 | 0.174 |

| Total Vitamin D (IU) | 315.6 ± 266.5 | 341.1 ± 291.1 | 0.402 |

The Association between RA and Hip Structural Geometry

A decrease in BMD and strength was observed over the nine years of study in all groups (Table 3). Though not statistically significant, after adjusting for age, the mean BMD and the hip geometry variables was smaller at baseline and each year of study in the RA group compared to the non-arthritic control group (Table 3). This trend was observed at all regions; however, the mean difference between the two groups was greatest at the narrow neck.

Table 3.

Age-Adjusted BMD and Hip Structural Geometry by RA Status at the Narrow Neck Region

| No Arthritis |

RA |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | p-value | |

| BMD (g/cm2) | |||

| Baseline | 0.717 ± 0.002 | 0.707 ± 0.013 | 0.468 |

| Year 3 | 0.726 ± 0.002 | 0.695 ± 0.018 | 0.093 |

| Year 6 | 0.716 ± 0.002 | 0.700 ± 0.021 | 0.457 |

| Year 9 | 0.702 ± 0.003 | 0.667 ± 0.026 | 0.181 |

| OD (cm) | |||

| Baseline | 2.998 ± 0.003 | 3.043 ± 0.024 | 0.067 |

| Year 3 | 3.015 ± 0.004 | 3.025 ± 0.031 | 0.753 |

| Year 6 | 3.026 ± 0.004 | 2.999 ± 0.038 | 0.480 |

| Year 9 | 3.068 ± 0.005 | 3.002 ± 0.050 | 0.190 |

| CSA (cm2) | |||

| Baseline | 2.041 ± 0.005 | 2.045 ± 0.039 | 0.917 |

| Year 3 | 2.078 ± 0.006 | 2.002 ± 0.052 | 0.150 |

| Year 6 | 2.057 ± 0.007 | 1.994 ± 0.063 | 0.318 |

| Year 9 | 2.045 ± 0.008 | 1.907 ± 0.077 | 0.074 |

| SM (cm3) | |||

| Baseline | 0.907 ± 0.003 | 0.923 ± 0.021 | 0.448 |

| Year 3 | 0.936 ± 0.003 | 0.901 ± 0.030 | 0.243 |

| Year 6 | 0.932 ± 0.004 | 0.918 ± 0.035 | 0.697 |

| Year 9 | 0.934 ± 0.005 | 0.871 ± 0.043 | 0.143 |

| BR | |||

| Baseline | 12.363 ± 0.038 | 12.766 ± 0.299 | 0.182 |

| Year 3 | 12.318 ± 0.044 | 12.930 ± 0.389 | 0.118 |

| Year 6 | 12.572 ± 0.049 | 12.943 ± 0.469 | 0.431 |

| Year 9 | 13.018 ± 0.067 | 13.548 ± 0.619 | 0.394 |

BMD=Bone Mineral Density; OD=Outer Diameter; CSA=Cross- Sectional Area; SM=Section Modulus; BR=Buckling Ratio

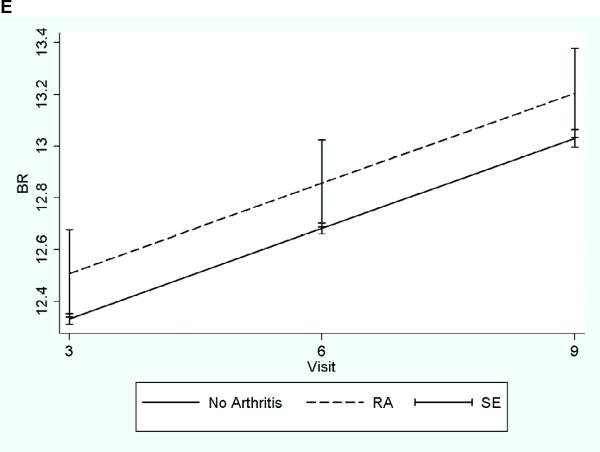

For the longitudinal analysis, no differential effect in hip strength was seen by age or ethnicity, and there was no statistical difference in the rate of loss between three groups over time. No statistically significant glucocorticoid (GC) interaction was also found using traditional interaction methods (main effect of arthritis * main effect of GC use). The final RCM was adjusted for visit and the following baseline variables: baseline strength parameter, age, ethnicity, clinical center, BMI, total body percent lean mass, randomization status (not randomized, intervention or placebo) in the CaD and HT trial, HT use, anticonvulsant medication use, osteoporosis medication use, and physical function. With incorporation of all time points in one model, significant declines in BMD and hip structural geometry variables were seen in the RA group compared to the non-arthritic control group (Table 4 & Figure 1). The RA group had a significantly lower mean OD, CSA, and SM over the study period at the narrow neck region. Though not statistically significant, the mean BMD was lower in the RA group than the nonarthritic control group, and the mean BR was higher (indicating decreased ability to resist local buckling) in the RA group than the non-arthritic control group. The magnitude of the association between RA and hip strength in the intertrochanteric and the shaft regions was not as large as at the narrow neck resulting in non-statistically significant effects, but similar decreasing trends in strength were seen in the RA group. Results from the random coefficient models for each region can be found on table 4 and the longitudinal graphs for the predicted narrow neck region can be found in Figure 1.

Table 4.

The Association between Rheumatoid Arthritis, BMD and Hip Structural Geometry based on Random Coefficient ModelA

| Narrow Neck |

Intertrochanteric |

Shaft |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| coef.B (95%CI) | coef.B (95% CI) | coef.B (95% CI) | |

| BMD | −0.013* (−0.027, 0.001) | −0.002 (−0.016, 0.011) | 0.002 (−0.018, 0.022) |

| OD | −0.035** (−0.064, −0.006) | 0.003 (−0.042, 0.047) | −0.008 (−0.029, 0.014) |

| CSA | −0.061*** (−0.102, −0.012) | −0.005 (−0.068, 0.058) | −0.003 (−0.055, 0.049) |

| SM | −0.027** (−0.052, −0.002) | −0.022 (−0.090, 0.046) | −0.015 (−0.050, 0.020) |

| BR | 0.175 (−0.158, 0.508) | 0.102 (−0.154, 0.358) | 0.006 (−0.094, 0.107) |

p<0.1;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

BMD=Bone Mineral Density; OD=Outer Diameter; CSA=Cross-Sectional Area; SM=Section Modulus; BR=Buckling Ratio

All models adjusted for visit, baseline age, ethnicity, center, BMI, total body % lean mass, CaD Trial arm, HT trial arm, hormone use, physical function, anticonvulsant medication use, and osteoporosis medication usage

BMD and HSA coefficients of RA reference to the no arthritis group are presented.

Figure 1. Longitudinal Changes in BMD and Hip Structural Geometry by Arthritis Status.

Longitudinal graph of predicted values from random coefficient model adjusted for mean value of the total population for continuous variables and mean proportion of total population for categorical variables.

A-Bone Mineral Density; B- Outer Diameter; C- Cross Sectional Area; D- Section Modulus; E-Buckling Ratio

DISCUSSION

Our study provides confirmation on the adverse effects of RA on hip BMD, and also showed that RA is associated with a decrease in structural integrity. Though small in number, the RA group within the WHI-BMD centers had reduced BMD and structural geometry at baseline, which further decreased throughout the nine years of study after adjustment for several variables. Inflammation, the primary driver of deteriorating bone health in RA patients, has been shown to be associated with markers of bone remodeling (36). Though not exclusively studied, one can hypothesize that inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, or other known inflammatory cytokine with adverse effects on osteoclasts, also have a negative effect on bone structure, providing molecular evidence for the declines in both bone quantity and quality in RA.

Although significant positive effects of various treatments on hip structure at all regions have been shown, our study only found significant results at the narrow neck region. For example, Bonnick and colleagues recently reported a significant effect at all regions with once weekly aledronate and risendronate therapy, with the treatment effect being the strongest at the intertrochanter (23). Our study showed similar trends in decreased strength in the intertrochanteric and shaft regions; however, the magnitude of the association between RA and hip structure was smaller in magnitude and unlike the narrow neck region, did not reach statistical significance. Systemic inflammation is a manifestation of RA, however, the joints are the primary region affected by the disease. Of the regions analyzed, the narrow neck is closest to the hip joint and its placement makes it either intracapsular or close to the capsule margin. This should make it more vulnerable to the erosive effects of the proliferative synovium of RA on bone mass and structure than the other regions, possibly explaining the findings of our study.

Though GC use has adverse effects on bone health, our study did not show any modification on the RA and hip geometry association by GC use. In the non-RA population, GC use slightly reduced the mean BMD and strength estimates to that of the GC negative RA population, and further slightly reduced BMD and strength estimates in the GC positive RA population. Studies on GC use and bone strength are limited. In 2007, Burnham and colleagues reported a study on the effects of glucocorticoid use on bone strength in a population of children with Crohn's disease and nephrotic syndrome (37). They found that cumulative glucocorticoid use was negatively correlated with and inversely associated with outer diameter and section modulus of the femur shaft region (37). Our study did not take into account dosage or cumulative use, which may alter the RA and geometry association, and the truncated sample size hindered statistical power.

Strengths and Limitations

The primary limitations of this study are related to the assessment of the RA. The WHI was not designed to be a RA specific study, and RA status is based solely on the respondent. Agreement estimates of self-reported RA to physician diagnoses range from 7–38% (38–42). The method used by Walitt and colleagues in a previous WHI study, showed that coupling medication information with self-report increased the positive predictive value (32). In the current study, only 14% of the self-reported RA cases indicated one of the medications of interest. The RA cases are probably true RA cases; however, these may represent the more severe cases, which could overestimate the effect of RA on hip strength. Using general RA population prevalence estimates, 1% or 114 women in the WHI-BMD centers should have an RA diagnosis. By using the baseline medication, we potentially captured only 60% of the cases, missing a significant number of likely RA cases. The addition of these unknown cases would provide more unbiased estimates of the associations between RA and hip strength. It is also possible that women with other rheumatologic conditions taking the medications of interest were misclassified as RA cases; however conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn's disease were ascertained in separate questions. The WHI also did not collect information on disease duration or severity, which potentially could modify the association between RA and hip strength.

There are also limitations associated with study outcome measurements. Three-dimensional hip structural geometry are being measured from a two-dimensional DXA scan, and several fundamental limitations have been noted (34). For example, it has been stated that DXA scanners are “optimized to measure mineral mass and not spatial dimensions”, hindering the machines ability to precisely measure structural parameters (34). The precision of femur geometry measurements is particularly dependent on subject positioning, much more than conventional BMD (34), making it more difficult to reliably detect small changes over time.

Though these limitations have been noted, the WHI ensured the quality of the data with a large number of quality control procedures. As previously stated, the DXA machines used at each of the centers were scanned using calibrated phantoms and any necessary corrections to the machine and clinic procedures were made over the study period. All DXA technicians were trained under manufacturer and WHI protocols, and there is no reason to suggest that the RA patients were positioned differently from the control group. Dedicated clinic staff also made sure the participants filled out all questionnaires so that complete information on covariates would be available. Examining the data longitudinally also provided the opportunity to increase the analytical power by including all time points in one model in addition to controlling for all other important covariates not examined in the cross-sectional analysis. The WHI is one of the largest and most diverse cohorts of postmenopausal women in the United States. There is a wealth of data within the WHI on longitudinal changes in bone strength and as well as information on important RA outcomes such as fractures, making it a good resource to assess the longitudinal effect of RA on bone loss, alterations is structural stability, and fracture risk.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a significant public health problem for older populations, and highly prevalent in RA populations. Osteoporotic fractures are a result of reduced bone strength, and with the advent of HSA, material and structural properties can be measured, providing a more complete strength estimate. With incorporation to many Hologic machines, the HSA program is now widely being used in the clinical and research arena. This investigation on RA and its effect on bone strength and changes over time, contributes epidemiological data to the field of rheumatology, which can be used to improve fracture assessment in women with rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks are extended to the staff of the Healthy Aging Laboratory for all of their help, and to the participants of the Women's Health Initiative. This work is a portion of NCW's dissertation work, which was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree at the University of Arizona.

Funding: This study was funded by National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases R01 AR049411-01A1 and R01 AR049411-04S1. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The hip structural analysis program used to ascertain the outcome was developed by Thomas Beck and licensed to Hologic Inc. by the Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Beck is also the founder of Quantum Medical Metrics LLC, a company dedicated to developing technology for measuring bone structural geometry. None of the other co-authors have conflicts of interests pertaining to this study.

SHORT LIST OF WHI INVESTIGATORS Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Elizabeth Nabel, Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Linda Pottern, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller.

Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). Ross Prentice, Garnet Anderson, Andrea LaCroix, Charles L. Kooperberg, Ruth E. Patterson, Anne McTiernan; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker; (Medical Research Labs, Highland Heights, KY) Evan Stein; (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA) Steven Cummings.

Clinical Centers: (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller; (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) Aleksandar Rajkovic; (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn Manson; (Brown University, Providence, RI) Annlouise R. Assaf; (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) Lawrence Phillips; (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Shirley Beresford; (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC) Judith Hsia; (Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor—UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA) Rowan Chlebowski; (Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, OR) Evelyn Whitlock; (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Oakland, CA) Bette Caan; (Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) Jane Morley Kotchen; (MedStar Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Northwestern University, Chicago/Evanston, IL) Linda Van Horn; (Rush Medical Center, Chicago, IL) Henry Black; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, NY) Dorothy Lane; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) Cora E. Lewis; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Tamsen Bassford; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of California at Davis, Sacramento, CA) John Robbins; (University of California at Irvine, CA) F. Allan Hubbell; (University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA) Lauren Nathan; (University of California at San Diego, LaJolla/Chula Vista, CA) Robert D. Langer; (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) Margery Gass; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI) David Curb; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Massachusetts/Fallon Clinic, Worcester, MA) Judith Ockene; (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, NJ) Norman Lasser; (University of Miami, Miami, FL) Mary Jo O'Sullivan; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen Margolis; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) Gerardo Heiss; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN) Karen C. Johnson; (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX) Robert Brzyski; (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) Gloria E. Sarto; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Mara Vitolins; (Wayne State University School of Medicine/Hutzel Hospital, Detroit, MI) Susan Hendrix.

References

- 1.Alamanos Y, Drosos AA. Epidemiology of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK. Bone mineral density and frequency of osteoporosis in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from 394 patients in the Oslo County Rheumatoid Arthritis register. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:522–530. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<522::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Cummings SR, Genant HK, Nevitt MC, Palermo L, Browner W. Axial and appendicular bone density predict fractures in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:633–638. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC., Jr. Baseline measurement of bone mass predicts fracture in white women. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:355–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-5-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melton LJ, 3rd, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Wahner HW, Riggs BL. Long-term fracture prediction by bone mineral assessed at different skeletal sites. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1227–1233. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melton LJ, 3rd, Wahner HW, Richelson LS, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Osteoporosis and the risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:254–261. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibuya K, Hagino H, Morio Y, Teshima R. Cross-sectional and longitudinal study of osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:150–158. doi: 10.1007/s10067-002-8274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lodder MC, de Jong Z, Kostense PJ, Molenaar ET, Staal K, Voskuyl AE, Hazes JM, Dijkmans BA, Lems WF. Bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: relation between disease severity and low bone mineral density. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1576–1580. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroot EJ, Nieuwenhuizen MG, de Waal Malefijt MC, van Riel PL, Pasker-de Jong PC, Laan RF. Change in bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during the first decade of the disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1254–1260. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1254::AID-ART216>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orstavik RE, Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Mowinckel P, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK. Self reported non-vertebral fractures in rheumatoid arthritis and population based controls: incidence and relationship with bone mineral density and clinical variables. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:177–182. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.005850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooyman JR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Nelson AM, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Fractures after rheumatoid arthritis. A population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:1353–1361. doi: 10.1002/art.1780271205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh NC, Crotti TN, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM. Rheumatic diseases: the effects of inflammation on bone. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:228–251. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein RS, Chen JR, Powers CC, Stewart SA, Landes RD, Bellido T, Jilka RL, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Promotion of osteoclast survival and antagonism of bisphosphonate-induced osteoclast apoptosis by glucocorticoids. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1041–1048. doi: 10.1172/JCI14538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canalis E, Bilezikian JP, Angeli A, Giustina A. Perspectives on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Bone. 2004;34:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, Zhang B, Cooper C. Oral corticosteroids and fracture risk: relationship to daily and cumulative doses. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1383–1389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watts NB, Ettinger B, LeBoff MS. FRAX facts. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:975–979. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith JF, Genant HK. Bone mass and architecture determination: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22:737–764. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnick SL. HSA: beyond BMD with DXA. Bone. 2007;41:S9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uusi-Rasi K, Beck TJ, Semanick LM, Daphtary MM, Crans GG, Desaiah D, Harper KD. Structural effects of raloxifene on the proximal femur: results from the multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation trial. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:575–586. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uusi-Rasi K, Semanick LM, Zanchetta JR, Bogado CE, Eriksen EF, Sato M, Beck TJ. Effects of teriparatide [rhPTH (1–34)] treatment on structural geometry of the proximal femur in elderly osteoporotic women. Bone. 2005;36:948–958. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck TJ, Stone KL, Oreskovic TL, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Effects of current and discontinued estrogen replacement therapy on hip structural geometry: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:2103–2110. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z, Beck TJ, Cauley JA, Lewis CE, LaCroix A, Bassford T, Wu G, Sherrill D, Going S. Hormone therapy improves femur geometry among ethnically diverse postmenopausal participants in the Women's Health Initiative hormone intervention trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1935–1945. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonnick SL, Beck TJ, Cosman F, Hochberg MC, Wang H, de Papp AE. DXA-based hip structural analysis of once-weekly bisphosphonate-treated postmenopausal women with low bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:911–921. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck TJ, Lewiecki EM, Miller PD, Felsenberg D, Liu Y, Ding B, Libanati C. Effects of denosumab on the geometry of the proximal femur in postmenopausal women in comparison with alendronate. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uusi-Rasi K, Sievanen H, Vuori I, Pasanen M, Heinonen A, Oja P. Associations of physical activity and calcium intake with bone mass and size in healthy women at different ages. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:133–142. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson RD, Wright NC, Beck TJ, Sherrill D, Cauley JA, Lewis CE, LaCroix AZ, LeBoff MS, Going S, Bassford T, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation has limited effects on femoral geometric strength in older postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;88:198–208. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9449-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivadeneira F, Zillikens MC, De Laet CE, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Beck TJ, Pols HA. Femoral neck BMD is a strong predictor of hip fracture susceptibility in elderly men and women because it detects cortical bone instability: the Rotterdam Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1781–1790. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaptoge S, Beck TJ, Reeve J, Stone KL, Hillier TA, Cauley JA, Cummings SR. Prediction of incident hip fracture risk by femur geometry variables measured by hip structural analysis in the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1892–1904. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lacroix AZ, Beck TJ, Cauley JA, Lewis CE, Bassford T, Jackson R, Wu G, Chen Z. Hip structural geometry and incidence of hip fracture in postmenopausal women: what does it add to conventional bone mineral density? Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:919–929. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1056-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher M, Allen C, Rossouw JE. The Women's Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S18–77. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walitt BT, Constantinescu F, Katz JD, Weinstein A, Wang H, Hernandez RK, Hsia J, Howard BV. Validation of self-report of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus: The Women's Health Initiative. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:811–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck TJ, Ruff CB, Warden KE, Scott WW, Jr., Rao GU. Predicting femoral neck strength from bone mineral data. A structural approach. Invest Radiol. 1990;25:6–18. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khoo BC, Beck TJ, Qiao QH, Parakh P, Semanick L, Prince RL, Singer KP, Price RI. In vivo short-term precision of hip structure analysis variables in comparison with bone mineral density using paired dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans from multi-center clinical trials. Bone. 2005;37:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DA, Barondess DA, Hendrix SL, Beck TJ. Cross-sectional geometry, bone strength, and bone mass in the proximal femur in black and white postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1992–1997. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Momohara S, Okamoto H, Yago T, Furuya T, Nanke Y, Kotake S, Soejima M, Mizumura T, Ikari K, Tomatsu T. The study of bone mineral density and bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with active rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2005;15:410–414. doi: 10.1007/s10165-005-0435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burnham JM, Shults J, Petit MA, Semeao E, Beck TJ, Zemel BS, Leonard MB. Alterations in proximal femur geometry in children treated with glucocorticoids for Crohn disease or nephrotic syndrome: impact of the underlying disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:551–559. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerhan JR, Saag KG, Merlino LA, Mikuls TR, Criswell LA. Antioxidant micronutrients and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in a cohort of older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:345–354. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costenbader KH, Feskanich D, Mandl LA, Karlson EW. Smoking intensity, duration, and cessation, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women. Am J Med. 2006;119:503, e501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlson EW, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Comparison of self-reported diagnosis of connective tissue disease with medical records in female health professionals: the Women's Health Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:652–660. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ling SM, Fried LP, Garrett E, Hirsch R, Guralnik JM, Hochberg MC. The accuracy of self-report of physician diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis in moderately to severely disabled older women. Women's Health and Aging Collaborative Research Group. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1390–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Star VL, Scott JC, Sherwin R, Lane N, Nevitt MC, Hochberg MC. Validity of self-reported rheumatoid arthritis in elderly women. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1862–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]